Influence of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Culture and Preparation

2.2. Antibacterial Assay

2.3. Analytic Methods

2.4. Sample Preparation and Analysis for Transcriptome Sequencing

2.5. Construction of Recombinant Strains

2.6. QRT-PCR Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

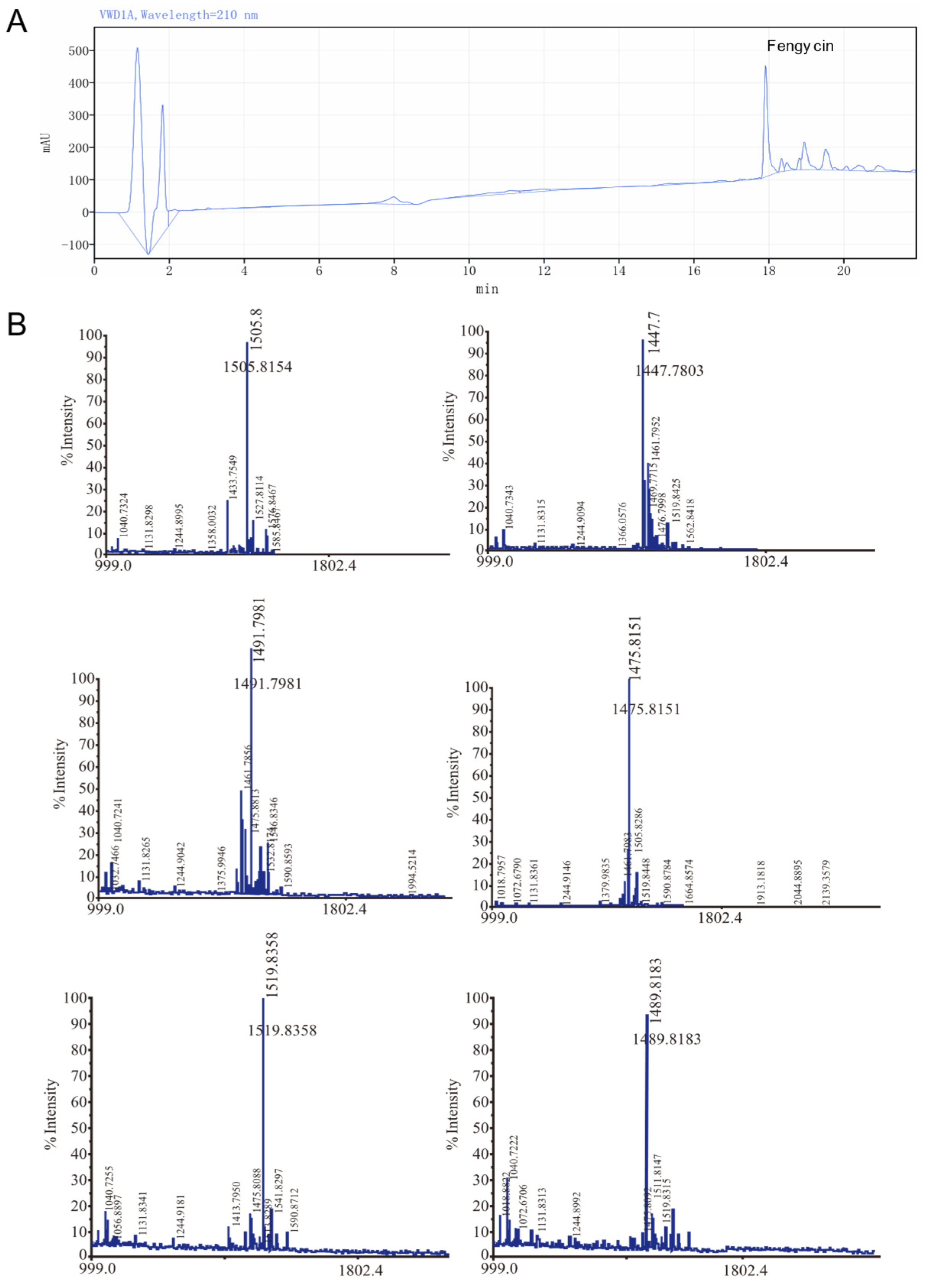

3.1. Identification of Fengycin Production in the Strain and Its Inhibitory Effect on Crop Pathogenic Fungi

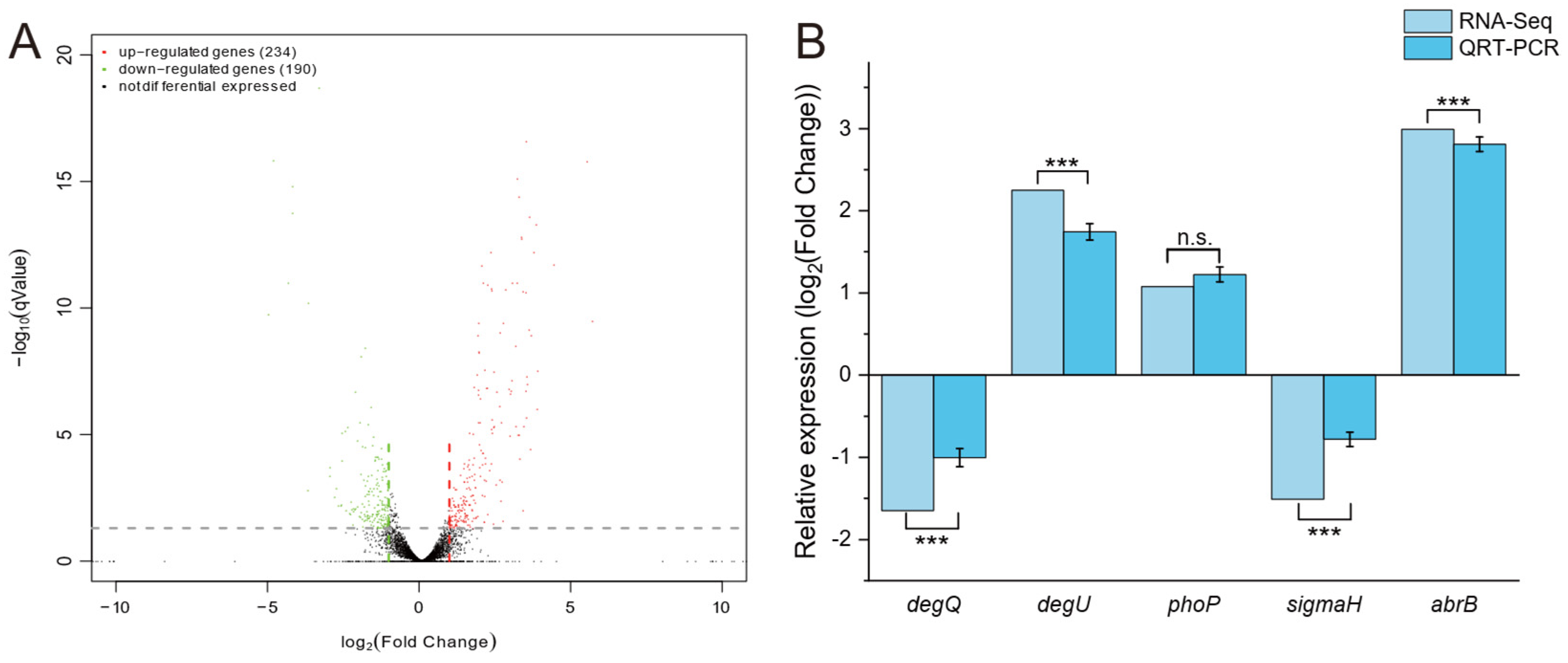

3.2. Identification of Global Regulators Associated with Fengycin Synthesis in B. amyloliquefaciens

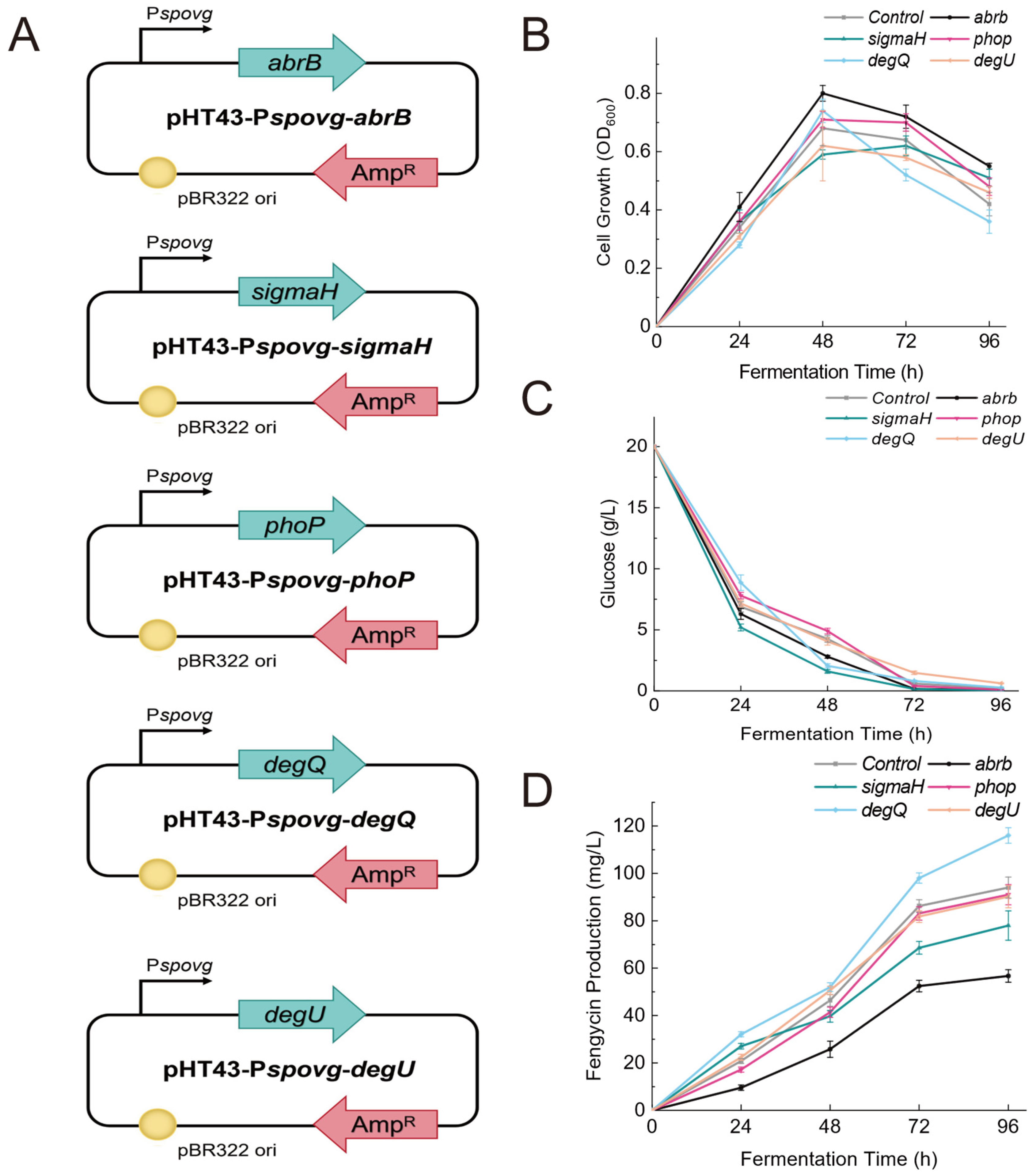

3.3. Effect of Overexpression of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis Level

3.4. Effect of Overexpression of Global Regulatory Factors on the Expression of Fengycin Synthesis Genes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P.; Wen, J. Strategies for improving fengycin production: A review. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valença, C.A.; Barbosa, A.A.; Dolabella, S.S.; Severino, P.; Matos, C.; Krambeck, K.; Souto, E.B.; Jain, S. Antimicrobial bacterial metabolites: Properties, applications and loading in liposomes for site-specific delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 2191–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmsten, M. Interactions of antimicrobial peptides with bacterial membranes and membrane components. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.B.; Shi, Z.Q.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Z.M. Fengycin antibiotics isolated from B-FS01 culture inhibit the growth of Fusarium moniliforme Sheldon ATCC 38932. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 272, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Tian, C.; Meng, X. Characterization of Bacillus velezensis YTQ3 as a potential biocontrol agent against Botrytis cinerea. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 223, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Dong, W.; Li, S.; Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, P. Fengycin produced by Bacillus subtilis NCD-2 plays a major role in biocontrol of cotton seedling damping-off disease. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, X. Fengycin Production and Its Applications in Plant Growth and Postharvest Quality. In Bio-Based Antimicrobial Agents to Improve Agricultural and Food Safety; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2024; pp. 71–119. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Escobar, V.; Ceballos, I.; Mira, J.J.; Argel, L.E.; Peralta, S.O.; Romero-Tabarez, M. Fengycin C produced by Bacillus subtilis EA-CB0015. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanif, A.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zubair, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J.; et al. Fengycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 inhibits Fusarium graminearum growth and mycotoxins biosynthesis. Toxins 2019, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ma, J.; Yin, Z.; Liu, K.; Yao, G.; Xu, W.; Fan, L.; Du, B.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C. Comparative genomic analysis of Bacillus paralicheniformis MDJK30 with its closely related species reveals an evolutionary relationship between B. paralicheniformis and B. licheniformis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qi, X.; Du, C. Biosynthesis and yield improvement strategies of fengycin. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, P. DegQ regulates the production of fengycins and biofilm formation of the biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis NCD-2. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 178, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, F.; Lu, Z.; Lu, Y. CodY, ComA, DegU and Spo0A controlling lipopeptides biosynthesis in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fmbJ. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Ping, M. The PhoR/PhoP two-component system regulates fengycin production in Bacillus subtilis NCD-2 under low-phosphate conditions. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Markelova, N.; Chumak, A. Antimicrobial activity of bacillus cyclic lipopeptides and their role in the host adaptive response to changes in environmental conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Sun, H.; Tang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, G.; Zhao, X. Transcription factor Spo0A regulates the biosynthesis of difficidin in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01044-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.F.; Liras, P.; Sánchez, S. Modulation of gene expression in actinobacteria by translational modification of transcriptional factors and secondary metabolite biosynthetic enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 630694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Cao, X.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Sha, C. Whole genome shotgun sequence of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28, a biocontrol entophytic bacterium. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2016, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Mahata, D.; Paul, D.; Korpole, S.; Franco, O.L.; Mandal, S.M. Purification, biochemical characterization and self-assembled structure of a fengycin-like antifungal peptide from Bacillus thuringiensis strain SM1. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanarajan, G.; Rangarajan, V.; Sridhar, P.R.; Sen, R. Development and scale-up of an efficient and green process for HPLC purification of antimicrobial homologues of commercially important microbial lipopeptides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 6638–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Shen, Z. Identification of lipopeptide isoforms by MALDI-TOF-MS/MS based on the simultaneous purification of iturin, fengycin, and surfactin by RP-HPLC. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 2529–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, W.; Meng, L.; Cao, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Development of a strain-specific quantification method for monitoring Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28 in the rhizospheric soil of soybean. Mol. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Höfte, M.; Hennessy, R.C. Does regulation hold the key to optimizing lipopeptide production in Pseudomonas for biotechnology? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1363183. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, Y.; Gancel, F.; Drider, D.; Béchet, M.; Jacques, P. Influence of promoters on the production of fengycin in Bacillus spp. Res. Microbiol. 2016, 167, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.-R.; Hou, Z.-J.; Ding, M.-Z.; Bai, S.; Wei, S.-Y.; Qiao, B.; Xu, Q.-M.; Cheng, J.-S.; Yuan, Y.-J. Improved production of fengycin in Bacillus subtilis by integrated strain engineering strategy. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 4065–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilge, L.; Vahidinasab, M.; Adiek, I.; Becker, P.; Nesamani, C.K.; Treinen, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Morabbi Heravi, K.; Henkel, M.; Hausmann, R. Expression of degQ gene and its effect on lipopeptide production as well as formation of secretory proteases in Bacillus subtilis strains. MicrobiologyOpen 2021, 10, e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danevčič, T.; Spacapan, M.; Dragoš, A.; Kovács, Á.T.; Mandic-Mulec, I. DegQ is an important policing link between quorum sensing and regulated adaptative traits in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00908-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Qiao, J.; Ali, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Song, Y.; Zhu, L.; Gu, Q.; Borriss, R.; Dong, S.; Gao, X.; et al. degQ associated with the degS/degU two-component system regulates biofilm formation, antimicrobial metabolite production, and biocontrol activity in Bacillus velezensis DMW1. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 24, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Enhanced control of plant wilt disease by a xylose-inducible degQ gene engineered into Bacillus velezensis strain SQR9XYQ. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhamme, D.T.; Murray, E.J.; Stanley-Wall, N.R. DegU and Spo0A jointly control transcription of two loci required for complex colony development by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, W.; He, S.; Lei, J.; Xu, L.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, D.; Chen, S. Understanding energy fluctuation during the transition state: The role of AbrB in Bacillus licheniformis. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausmann, P.; Lilge, L.; Aschern, M.; Hennemann, K.; Henkel, M.; Hausmann, R.; Morabbi Heravi, K. Influence of B. subtilis 3NA mutations in spo0A and abrB on surfactin production in B. subtilis 168. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Mobile Phase Conditions | Flow Rate (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|

| 0–4 min | Solvent B: increased from 40% to 45% | 2 mL/min |

| 4–11 min | Solvent B: increased from 45% to 60% | 0.8 mL/min |

| 11–17 min | Solvent B: increased from 65% to 70% | 0.4 mL/min |

| 17–22 min | Solvent B: increased from 70% to 85% | 1.5 mL/min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, G.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Y.; Xia, H.; Tian, Y.; Yu, C. Influence of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28. Fermentation 2026, 12, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020072

Yan G, Zhou L, Xu Y, Xia H, Tian Y, Yu C. Influence of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28. Fermentation. 2026; 12(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Gengxuan, Lu Zhou, Yan Xu, Haihua Xia, Yuan Tian, and Chong Yu. 2026. "Influence of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28" Fermentation 12, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020072

APA StyleYan, G., Zhou, L., Xu, Y., Xia, H., Tian, Y., & Yu, C. (2026). Influence of Global Regulatory Factors on Fengycin Synthesis by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28. Fermentation, 12(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020072