Schizophrenia and Hospital Admissions for Cardiovascular Events in a Large Population: The APNA Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Variables

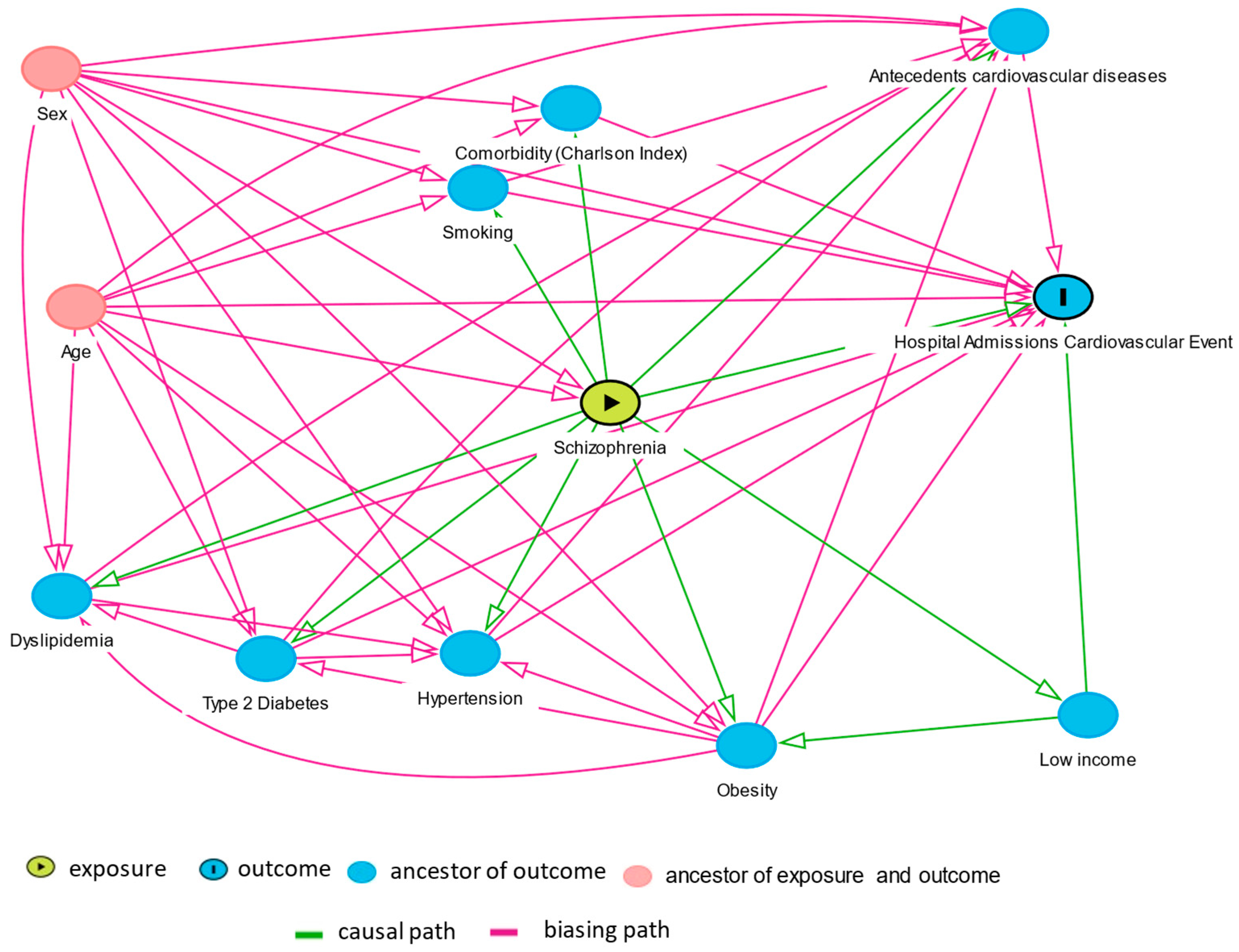

2.2. Statistical Analysis

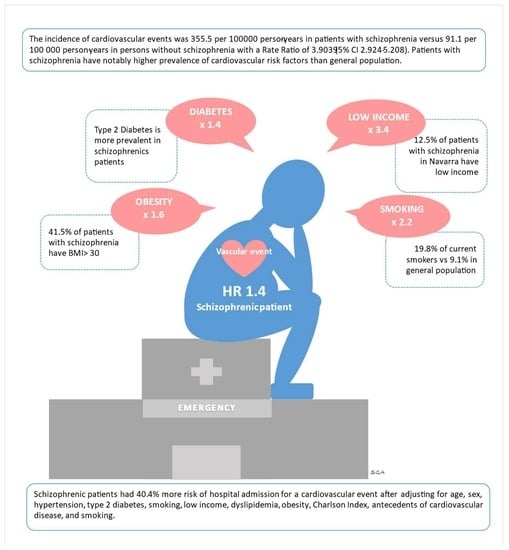

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lavagnino, L.; Gurguis, C.; Lane, S. Risk Factors for Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease in Inpatients with Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 304, 114148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; McGrath, J. A Systematic Review of Mortality in Schizophrenia: Is the Differential Mortality Gap Worsening over Time? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.C.; Shoesmith, W.D.; Al Mamun, M.; Abdullah, A.F.; Naing, D.K.S.; Phanindranath, M.; Turin, T.C. Cardiovascular Diseases among Patients with Schizophrenia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016, 19, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno-Küstner, B.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Pardo, Y.; Sanchidrián, Y.; Díaz-Ruiz, S.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Excess Mortality in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders in Malaga (Spain): A Cohort Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marche, J.-C.; Bannay, A.; Baillot, S.; Dauriac-Le Masson, V.; Leveque, P.; Schmitt, C.; Laprévote, V.; Schwan, R.; Dobre, D. Prevalence of Severe Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Schizophrenia. Encephale. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleetwood, K.; Wild, S.H.; Smith, D.J.; Mercer, S.W.; Licence, K.; Sudlow, C.L.M.; Jackson, C.A. Severe Mental Illness and Mortality and Coronary Revascularisation Following a Myocardial Infarction: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.W.; Lee, E.S.; Toh, M.P.H.S.; Lum, A.W.M.; Seah, D.E.J.; Leong, K.P.; Chan, C.Y.W.; Fung, D.S.S.; Tor, P.C. Comparison of Mental-Physical Comorbidity, Risk of Death and Mortality among Patients with Mental Disorders—A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 142, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Rosenheck, R. Compliance With Medication Regimens for Mental and Physical Disorders. Psychiatr. Serv. 1998, 49, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, J.; Long, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hei, G.; Sun, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; et al. Optimizing and Individualizing the Pharmacological Treatment of First-Episode Schizophrenic Patients: Study Protocol for a Multicenter Clinical Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 611070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Lange, S.M.M. Metabolic Syndrome in Psychiatric Patients: Overview, Mechanisms, and Implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, F.-M.; Covenas, R. Long-Term Administration of Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia and Influence of Substance and Drug Abuse on the Disease Outcome. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2017, 10, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.M. Strategies for the Long-Term Treatment of Schizophrenia: Real-World Lessons from the CATIE Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68 (Suppl. 1), 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ratna, V.V.J.; Vempadapu, M.; Kolakota, R.K.; Mugada, V. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Schizophrenia: A Mini Review. Asian J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rodriguez, E.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Martí, A.; Brugos-Larumbe, A. Comorbidity Associated with Obesity in a Large Population: The APNA Study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 9, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Palacios, S.; Llavero Valero, M.; Brugos-Larumbe, A.; Díez, J.J.; Guillén-Grima, F.; Galofré, J.C. Prevalence of Thyroid Dysfunction in a Large Southern European Population. Analysis of Modulatory Factors. The APNA Study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 89, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Rodriguez, E.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Aubá, E.; Martí, A.; Brugos-Larumbe, A. Relationship between Body Mass Index and Depression in Women: A 7-Year Prospective Cohort Study. The APNA Study. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 32, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugos-Larumbe, A.; Aldaz-Herce, P.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Garjón-Parra, F.J.; Bartolomé-Resano, F.J.; Arizaleta-Beloqui, M.T.; Pérez-Ciordia, I.; Fernández-Navascués, A.M.; Lerena-Rivas, M.J.; Berjón-Reyero, J.; et al. Assessing Variability in Compliance with Recommendations given by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care Using Electronic Records. The APNA Study. Prim. Care Diabetes 2018, 12, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Guillen-Aguinaga, S.; Pereira-Sanchez, V.; Onambele, L.; Al-Rahamneh, M.J.; Brugos-Larumbe, A.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Ortuño, F. Being Born in Winter-Spring and at Around the Time of an Influenza Pandemic Are Risk Factors for the Development of Schizophrenia: The Apna Study in Navarre, Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen-Aguinaga, S.; Forga, L.; Brugos-Larumbe, A.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Guillen-Aguinaga, L.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. Variability in the Control of Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care and Its Association with Hospital Admissions for Vascular Events. The APNA Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real Decreto-Ley 16/2012, de 20 de Abril, de medidas urgentes para garantizar la sostenibilidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud y mejorar la calidad y seguridad de sus prestaciones. Boletín Of. del Estado 2012, 98, 31278–31312.

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Li, B.; Couris, C.M.; Fushimi, K.; Graham, P.; Hider, P.; Januel, J.-M.; Sundararajan, V. Updating and Validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Score for Risk Adjustment in Hospital Discharge Abstracts Using Data from 6 Countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haddad, P.; Brain, C.; Scott, J. Nonadherence with Antipsychotic Medication in Schizophrenia: Challenges and Management Strategies. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2014, 2014, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velligan, D.I.; Lam, Y.-W.F.; Glahn, D.C.; Barrett, J.A.; Maples, N.J.; Ereshefsky, L.; Miller, A.L. Defining and Assessing Adherence to Oral Antipsychotics: A Review of the Literature. Schizophr. Bull. 2005, 32, 724–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lederer, D.J.; Bell, S.C.; Branson, R.D.; Chalmers, J.D.; Marshall, R.; Maslove, D.M.; Ost, D.E.; Punjabi, N.M.; Schatz, M.; Smyth, A.R.; et al. Control of Confounding and Reporting of Results in Causal Inference Studies. Guidance for Authors from Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernán, M.; Robins, J. CausalInference: What If; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T.H. Robust Causal Inference Using Directed Acyclic Graphs: The R Package ‘Dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Versión 3.01. Available online: https://www.openepi.com/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Abidi, O.; Vercherin, P.; Massoubre, C.; Bois, C. Le Risque Cardiovasculaire Global Des Patients Atteints de Schizophrénie Hospitalisés En Psychiatrie Au CHU de Saint-Étienne. Encephale. 2019, 45, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Kural, K.C.; Cao, H.; Li, Y. Schizophrenia Plays a Negative Role in the Pathological Development of Myocardial Infarction at Multiple Biological Levels. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 607690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corfdir, C.; Pignon, B.; Szöke, A.; Schürhoff, F. Accelerated Telomere Erosion in Schizophrenia: A Literature Review. Encephale 2021, 47, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravane, D.; Feve, B.; Frances, Y.; Corruble, E.; Lancon, C.; Chanson, P.; Maison, P.; Terra, J.-L.; Azorin, J.-M. Élaboration de Recommandations Pour Le Suivi Somatique Des Patients Atteints de Pathologie Mentale Sévère. Encephale 2009, 35, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Fiedorowicz, J.; Poddighe, L.; Delogu, M.; Miola, A.; Høye, A.; Heiberg, I.H.; Stubbs, B.; Smith, L.; Larsson, H.; et al. Disparities in Screening and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases in Patients with Mental Disorders Across the World: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 47 Observational Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 9, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapral, M.K.; Kurdyak, P.; Casaubon, L.K.; Fang, J.; Porter, J.; Sheehan, K.A. Stroke Care and Case Fatality in People with and without Schizophrenia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemogne, C.; Blacher, J.; Airagnes, G.; Hoertel, N.; Czernichow, S.; Danchin, N.; Meneton, P.; Limosin, F.; Fiedorowicz, J.G. Management of Cardiovascular Health in People with Severe Mental Disorders. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.T.T.; Guthrie, B.; Mercer, S.W.; Smith, D.J.; Yip, B.H.K.; Chung, G.K.K.; Lee, K.-P.; Chung, R.Y.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Wong, E.L.Y.; et al. Association between Antipsychotic Use and Acute Ischemic Heart Disease in Women but Not in Men: A Retrospective Cohort Study of over One Million Primary Care Patients. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Leu, S.-J.J.; Hsu, C.-P.; Pan, C.-C.; Shyue, S.-K.; Lee, T.-S. Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs Deregulate the Cholesterol Metabolism of Macrophage-Foam Cells by Activating NOX-ROS-PPARγ-CD36 Signaling Pathway. Metabolism 2021, 123, 154847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Cruz, E.C.; Zandonadi, F.d.S.; Fontes, W.; Sussulini, A. A Pilot Study Indicating the Dysregulation of the Complement and Coagulation Cascades in Treated Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Patients. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Proteins Proteom. 2021, 1869, 140657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Welham, J.; Chant, D.; McGrath, J. Incidence of Schizophrenia Does Not Vary with Economic Status of the Country: Evidence from a Systematic Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, P.; Juel, A.; Hansen, M.V.; Madsen, N.J.; Viuff, A.G.; Munk-Jørgensen, P. Reducing the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases in Non-Selected Outpatients With Schizophrenia: A 30-Month Program Conducted in a Real-Life Setting. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, P.; Vojtila, L.; Ashfaq, I.; Dragonetti, R.; Melamed, O.C.; Carriere, R.; LaChance, L.; Kohut, S.A.; Hahn, M.; Mulsant, B.H. Technology-Enabled Collaborative Care for Youth with Early Psychosis: A Protocol for a Feasibility Study to Improve Physical Health Behaviours. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, A.; Sharps, P.; Kverno, K.; RachBeisel, J.; Gorth, M. A 12-Week Evidence-Based Education Project to Reduce Cardiovascular and Metabolic Risk in Adults With Serious Mental Illness in the Integrated Care Setting. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 27, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Schizophrenia N = 2495 | No Schizophrenia N = 503,394 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | % Mean (SD) | % Mean (SD) | p |

| Age (years) | 49.7 (15.7) | 50.0 (18.0) | 0.342 † |

| Male | 59.8% | 49.2% | <0.001 ‡ |

| Low income | 12.9% | 3.8% | <0.001 ‡ |

| Charlson Index | 1.3 (1.8) | 1.3 (1.7) | 0.677 * |

| Comorbidity Index | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.7) | 0.512 * |

| (Obesity) BMI ≥ 30 | 41.5% | 25.9% | <0.001 ‡ |

| BMI | 29.4 (6.3) | 27.2 (5.2) | <0.001 † |

| CV antecedents | 8.9% | 9.5% | 0.243 ‡ |

| Diabetes | 7.8% | 5.4% | <0.001 ‡ |

| Hypertension | 12.5% | 15.1% | 0.001 ‡ |

| Dyslipidemia | 27.1% | 25.9% | 0.221 ‡ |

| Smoking | 19.8% | 9.1% | <0.001 ‡ |

| Medications | N | % * |

|---|---|---|

| Oxazepine and thiazepine | 984 | 39.5 |

| Risperidone | 482 | 19.3 |

| Olanzepine | 451 | 18.1 |

| Clozapine | 264 | 10.6 |

| Quetiapine | 238 | 9.5 |

| Clotiapine | 128 | 5.1 |

| Asenapine | 8 | 0.3 |

| Model Adjusted by Age and Sex | Model Adjusted * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Schizophrenia | 1.348 (1.009–1.801) | 0.044 | 1.421 (1.037–1.948) | 0.029 |

| Model Adjusted by Age and Sex | Full Model Adjusted * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| No schizophrenia | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Treated schizophrenia | 1.206 (0.848–1.717) | 0.297 | 1.224 (0.838–1.267) | 0.296 |

| Non-adherence to antipsychotic treatment | 1.778 (1.071–2.951) | 0.026 | 2.232 (1.267–3.933) | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.077 (1.076–1.079) | <0.001 | 1.044 (1.042–1.046)) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 2.465 (2.355–2.580) | <0.001 | 1.953 (1.857–2.054) | <0.001 |

| High blood pressure | - | - | 1.143 (1.076–1.189) | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | - | - | 1.531 (1.451–1.615) | <0.001 |

| Antecedents CVE | - | - | 6.559 (6.218–6.919) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | - | - | 1.134 (1.046–1.230) | 0.002 |

| Low income | - | - | 1.494 (1.307–1.709) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia diagnosis or total cholesterol > 250 mg/dL | - | - | 1.080 (1.030–1.132) | 0.001 |

| Obesity BMI ≥ 30 | - | - | 1.145 (1.090–1.203) | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guillen-Aguinaga, S.; Brugos-Larumbe, A.; Guillen-Aguinaga, L.; Ortuño, F.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Forga, L.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. Schizophrenia and Hospital Admissions for Cardiovascular Events in a Large Population: The APNA Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9010025

Guillen-Aguinaga S, Brugos-Larumbe A, Guillen-Aguinaga L, Ortuño F, Guillen-Grima F, Forga L, Aguinaga-Ontoso I. Schizophrenia and Hospital Admissions for Cardiovascular Events in a Large Population: The APNA Study. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2022; 9(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuillen-Aguinaga, Sara, Antonio Brugos-Larumbe, Laura Guillen-Aguinaga, Felipe Ortuño, Francisco Guillen-Grima, Luis Forga, and Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso. 2022. "Schizophrenia and Hospital Admissions for Cardiovascular Events in a Large Population: The APNA Study" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 9, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9010025

APA StyleGuillen-Aguinaga, S., Brugos-Larumbe, A., Guillen-Aguinaga, L., Ortuño, F., Guillen-Grima, F., Forga, L., & Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. (2022). Schizophrenia and Hospital Admissions for Cardiovascular Events in a Large Population: The APNA Study. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 9(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9010025

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)