Evaluation of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Neonates with Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated with Ibuprofen or Indomethacin: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

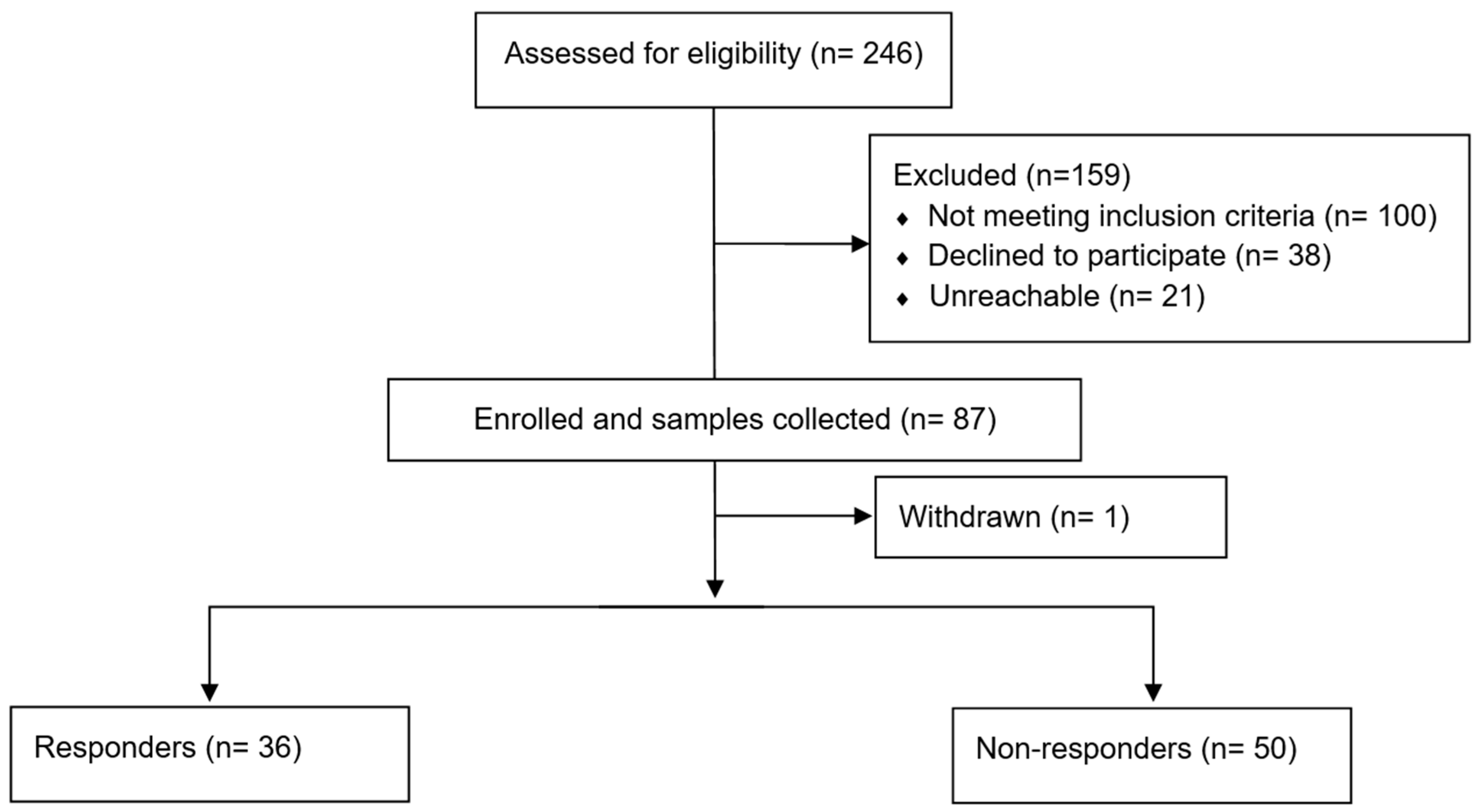

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. DNA Quantification

2.5. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Detection and Genotyping

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nebert, D.W. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics: Why is this relevant to the clinical geneticist? Clin. Genet. 1999, 56, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H. Right patient, right treatment, right time: Biosignatures and precision medicine in depression. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaik, R.H. Clinical Application of Pharmacogenetics: Where are We Now? Ejifcc 2013, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Driest, S.L.; McGregor, T.L. Pharmacogenetics in clinical pediatrics: Challenges and strategies. Pers. Med. 2013, 10, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Leroux, S.; Biran, V.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. Developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2C19 in neonates and young infants: Omeprazole as a probe drug. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmer, A.; Bjerre, J.V.; Schmidt, M.R.; McNamara, P.J.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Høst, B.; Bech, B.H.; Henriksen, T.B. Morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus on day 3. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013, 98, F505–F510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, S.E.; Hansmann, G. Patent ductus arteriosus of the preterm infant. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, C.H.; Hill, K.D.; Shelton, E.L.; Slaughter, J.L.; Lewis, T.R.; Weisz, D.E.; Mah, M.L.; Bhombal, S.; Smith, C.V.; McNamara, P.J.; et al. Patent Ductus Arteriosus: A Contemporary Perspective for the Pediatric and Adult Cardiac Care Provider. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.C.; Tillett, A.; Tulloh, R.; Yates, R.; Kelsall, W. Outcome following patent ductus arteriosus ligation in premature infants: A retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2006, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yoon, S.J.; Han, J.; Song, I.G.; Lim, J.; Shin, J.E.; Eun, H.S.; Park, K.I.; Park, M.S.; Lee, S.M. Patent ductus arteriosus treatment trends and associated morbidities in neonates. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, K.C.; Corff, K.E. Treatment of patent ductus arteriosus: Indomethacin or ibuprofen? J. Perinatol. 2008, 28, S60–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.L.; Parker, G.C.; Van Overmeire, B.; Aranda, J.V. A meta-analysis of ibuprofen versus indomethacin for closure of patent ductus arteriosus. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2005, 164, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Walia, R.; Shah, S.S. Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm and/or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 30, Cd003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Walia, R.; Shah, S.S. Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight (or both) infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, Cd003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.; O’Reilly, D.; Flyer, J.N.; Soll, R.; Mitra, S. Indomethacin for symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, Cd013133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisz, D.E.; Mirea, L.; Rosenberg, E.; Jang, M.; Ly, L.; Church, P.T.; Kelly, E.; Kim, S.J.; Jain, A.; McNamara, P.J.; et al. Association of Patent Ductus Arteriosus Ligation With Death or Neurodevelopmental Impairment Among Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.J.; Ryckman, K.K.; Bahr, T.M.; Dagle, J.M. Polymorphisms in CYP2C9 are associated with response to indomethacin among neonates with patent ductus arteriosus. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G.; Martínez, C.; García-Martín, E.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Cytochrome P450 Gene Polymorphisms and Variability in Response to NSAIDs. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 2005, 22, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, V.; Dimovski, A.; Domjanović, I.K.; Bilić, I.; Božina, N. How polymorphisms of the cytochrome P450 genes affect ibuprofen and diclofenac metabolism and toxicity. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2016, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T. Chapter 12—Neonatal Pharmacogenetics. In Infectious Disease and Pharmacology; Benitz, W.E., Smith, P.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Dong, X.; Lu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W. CYP2C9*3 Increases the Ibuprofen Response of Hemodynamically Significant Patent Ductus Arteriosus in the Infants with Gestational Age of More Than 30 Weeks. Phenomics 2022, 2, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCY. 150 mm Medical Disposable Sampling Tube for Saliva Collecting. Available online: https://icleanswabs.com/ (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- PROMEGA. Maxwell® 16 DNA Purification Kits Technical Manual. Available online: https://worldwide.promega.com/resources/protocols/technical-manuals/0/maxwell-16-dna-purification-kits-protocol/ (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c Spectrophotometers. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/ND-2000 (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. TaqMan™ Drug Metabolism Genotyping Assay. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/4362691?SID=srch-srp-4362691 (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. TaqMan™ SNP Genotyping Assay, Human. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/4331349?SID=srch-srp-4331349 (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Sallmon, H.; Aydin, T.; Hort, S.; Kubinski, A.; Bode, C.; Klippstein, T.; Endesfelder, S.; Bührer, C.; Koehne, P. Vascular endothelial growth factor polymorphism rs2010963 status does not affect patent ductus arteriosus incidence or cyclooxygenase inhibitor treatment success in preterm infants. Cardiol. Young 2019, 29, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagle, J.M.; Lepp, N.T.; Cooper, M.E.; Schaa, K.L.; Kelsey, K.J.; Orr, K.L.; Caprau, D.; Zimmerman, C.R.; Steffen, K.M.; Johnson, K.J.; et al. Determination of genetic predisposition to patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, J.G.; Evans, F.J.; Burns, K.M.; Pearson, G.D.; Kaltman, J.R. Surgical ligation of patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants: Trends and practice variation. Cardiol. Young 2016, 26, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagle, J.M.; Ryckman, K.K.; Spracklen, C.N.; Momany, A.M.; Cotten, C.M.; Levy, J.; Page, G.P.; Bell, E.F.; Carlo, W.A.; Shankaran, S.; et al. Genetic variants associated with patent ductus arteriosus in extremely preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.; Scott, T.A.; Patrick, S.W. Changing patterns of patent ductus arteriosus surgical ligation in the United States. Semin. Perinatol. 2018, 42, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.; Abdul Haium, A.A.; Tapawan, S.J.; Dela Puerta, R.; Allen, J.C., Jr.; Chandran, S.; Chua, M.C.; Rajadurai, V.S. Selective Treatment of PDA in High-Risk VLBW Infants With Birth Weight ≤800 g or <27 Weeks and Short-Term Outcome: A Cohort Study. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 607772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, S.R.; Shelton, E.L.; Aka, I.; Shaffer, C.M.; Clyman, R.I.; Dagle, J.M.; Ryckman, K.; Lewis, T.R.; Reese, J.; Van Driest, S.L.; et al. CYP2C9*2 is associated with indomethacin treatment failure for patent ductus arteriosus. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khuffash, A.; Mullaly, R.; McNamara, P.J. Patent ductus arteriosus, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary hypertension—A complex conundrum with many phenotypes? Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyman, R.I.; Hills, N.K. Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and pulmonary morbidity: Can early targeted pharmacologic PDA treatment decrease the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia? Semin. Perinatol. 2023, 47, 151718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyman, R.I.; Kaempf, J.; Liebowitz, M.; Erdeve, O.; Bulbul, A.; Håkansson, S.; Lindqvist, J.; Farooqi, A.; Katheria, A.; Sauberan, J.; et al. Prolonged Tracheal Intubation and the Association Between Patent Ductus Arteriosus and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: A Secondary Analysis of the PDA-TOLERATE trial. J. Pediatr. 2021, 229, 283–288.e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyman, R.I.; Hills, N.K. The effect of prolonged tracheal intubation on the association between patent ductus arteriosus and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (grades 2 and 3). J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, K.; Al Jufairi, M.; Al Ansari, E.; Jasim, A.; Eltayeb Diab, D.; Al Marzooq, R.; Al Madhoob, A. Evaluation of urinary acetaminophen metabolites and its association with the genetic polymorphisms of the metabolising enzymes, and serum acetaminophen concentrations in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus. Xenobiotica 2021, 51, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | SNP Name | Alleles | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8 | (* 3) rs10509681 | T > C | Decreased clearance |

| CYP2C9 | (* 2) rs1799853 | C > T | Decreased function |

| CYP2C9 | rs2153628 | A > G | Decreased clearance |

| CYP2C9 | (* 3) rs1057910 | A > C | No function |

| Reaction Component | Volumes per Well (96-Well Plate) |

|---|---|

| DME (rs10509681, rs1799853, rs1057910) | |

| TaqMan Master Mix 2X | 12.5 µL |

| 20X Assay Working Stock | 1.25 µL |

| Nuclease-Free Water | 0 µL |

| DNA | 11.25 µL |

| Total Volume Per Well | 25 µL |

| SNP (rs2153628) | |

| TaqMan Master Mix 2× | 5 µL |

| Genotyping Assay Mix 20× | 0.5 µL |

| DNA | 4.5 µL |

| Total Volume Per Well | 10 µL |

| Step | Temperature | Duration | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| DME (rs10509681, rs1799853, rs1057910) | |||

| AmpliTaq GoldR, UP, Enzyme Activation | 95 °C | 10 min | HOLD |

| Denaturation | 92 °C | 15 s | 50 |

| Annealing/Extension | 60 °C | 90 s | 50 |

| SNP (rs2153628) | |||

| AmpliTaq GoldR, UP, Enzyme Activation | 95 °C | 10 min | HOLD |

| Denaturation | 95 °C | 15 s | 40 |

| Annealing/Extension | 60 °C | 1 min | 40 |

| Characteristic | Non-Responders (n = 50) | Responders (n = 36) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA (weeks)—median (IQR) | 25.1 (2.8) | 26.3 (2.9) | 0.148 |

| Birth weight category—n (%) | 0.033 | ||

| VLBW | 7 (14) | 12 (33.3) | |

| ELBW | 43 (86) | 24 (66.7) | |

| Age on first day of treatment (days)—median (IQR) | 8.5 (6.8) | 8 (5.3) | 0.298 |

| Male sex—n (%) | 29 (58) | 19 (52.8) | 0.63 |

| Ethnicity—n (%) | 0.589 | ||

| Middle Eastern | 28 (56) | 22 (61.1) | |

| Asian | 18 (36) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Black | 3 (6) | 4 (11.1) | |

| White | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Delivery mode—n (%) | 0.967 | ||

| NVD | 28 (56) | 20 (55.6) | |

| CS | 22 (44) | 16 (44.4) | |

| Singleton pregnancy—n (%) | 32 (64) | 28 (77.8) | 0.17 |

| APGAR score at 1 min—median (IQR) | 5.5 (3.8) | 5 (4.3) | 0.94 |

| APGAR score at 5 min—median (IQR) | 7.5 (1) | 8 (3) | 0.419 |

| Chorioamnionitis—n (%) | 6 (12) | 2 (5.6) | 0.31 |

| Antenatal steroid use—n (%) | 41 (82) | 30 (83.3) | 0.872 |

| Surfactant use—n (%) | 45 (90) | 33 (91.7) | 0.793 |

| Surfactant doses—n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| 1 | 10 (21.7) | 17 (51.5) | |

| 2 | 35 (76.1) | 14 (42.4) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Resuscitation mode—n (%) | 0.196 | ||

| Noninvasive | 7 (14) | 9 (25) | |

| Invasive | 43 (86) | 27 (75) | |

| RDS severity—n (%) | 0.798 | ||

| Mild | 13 (26) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Moderate | 17 (34) | 11 (30.6) | |

| Severe | 20 (40) | 17 (47.2) | |

| Prior paracetamol use—n (%) | 5 (10) | 2 (5.6) | 0.457 |

| Respiratory support on first day of treatment—n (%) | 0.119 | ||

| Noninvasive | 15 (30) | 17 (47.2) | |

| CMV | 32 (64) | 15 (41.7) | |

| HFOV | 3 (6) | 4 (11.1) | |

| Pre-treatment serum creatinine—mean (SD) | 56.9 (11.8) | 53.9 (17.7) | 0.418 |

| SNPs | All Patients | Non-Responders (n = 50) | Responders (n = 36) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*3 rs10509681 | 0.884 | |||

| Wild type (TT) | 36 (41.9) | 20 (40) | 16 (44) | |

| Heterozygous (TC) | 39 (45.3) | 23 (46) | 16 (44) | |

| Homozygous (CC) | 11 (12.8) | 7 (14) | 4 (11) | |

| CYP2C9*2 rs1799853 | 0.388 | |||

| Missing (n = 3) | ||||

| Wild type (CC) | 68 (81.9) | 41 (82) | 27 (75) | |

| Heterozygous (CT) | 14 (16.9) | 7 (14) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Homozygous (TT) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | |

| CYP2C9 rs2153628 | 0.507 | |||

| Missing (n = 23) | ||||

| Wild type (AA) | 34 (39.5) | 20 (40) | 14 (38) | |

| Heterozygous (AG) | 27 (31.4) | 16 (32) | 11 (30.5) | |

| Homozygous (GG) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (4) | 0 | |

| CYP2C9*3 rs1057910 | 0.928 | |||

| Missing (n = 2) | ||||

| Wild type (AA) | 72 (83) | 41 (82) | 31 (86) | |

| Heterozygous (AC) | 12 (13.9) | 7 (14) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Values are presented as n (%). | ||||

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| GA | 1.165 | 0.907–1.506 | 0.148 | 1.020 | 0.694–1.50 | 0.921 |

| ELBW | 0.326 | 0.098–0.695 | 0.007 | 0.281 | 0.062–1.268 | 0.099 |

| Need for 2+ doses | 0.261 | 0.084–0.625 | 0.004 | 0.244 | 0.086–0.693 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alnaimi, S.J.; Aboelbaha, S.; Safra, I.; Al Qubaisi, M.A.; Abounahia, F.; Al Farsi, A.; Cherian, L.; Philip, L.; Alhail, M.; Sher, G.; et al. Evaluation of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Neonates with Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated with Ibuprofen or Indomethacin: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010049

Alnaimi SJ, Aboelbaha S, Safra I, Al Qubaisi MA, Abounahia F, Al Farsi A, Cherian L, Philip L, Alhail M, Sher G, et al. Evaluation of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Neonates with Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated with Ibuprofen or Indomethacin: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlnaimi, Shaikha Jabor, Shimaa Aboelbaha, Ibrahim Safra, Mai Abdulla Al Qubaisi, Fouad Abounahia, Ahmed Al Farsi, Liji Cherian, Lizy Philip, Moza Alhail, Gulab Sher, and et al. 2026. "Evaluation of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Neonates with Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated with Ibuprofen or Indomethacin: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010049

APA StyleAlnaimi, S. J., Aboelbaha, S., Safra, I., Al Qubaisi, M. A., Abounahia, F., Al Farsi, A., Cherian, L., Philip, L., Alhail, M., Sher, G., & Al-Dewik, N. (2026). Evaluation of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Neonates with Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated with Ibuprofen or Indomethacin: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010049