Intravascular Imaging for Facilitated Coronary Interventions in DES Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

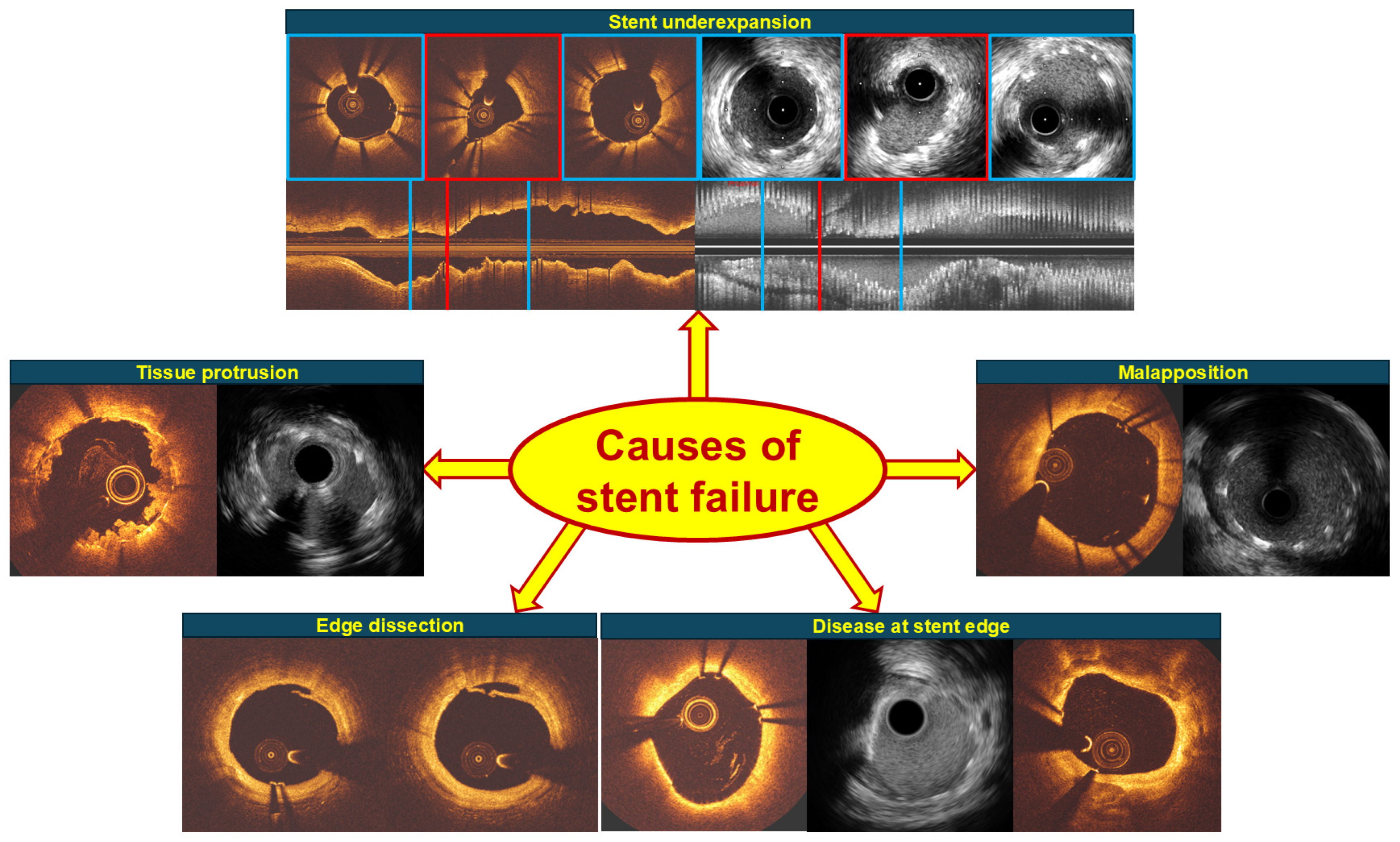

2. Intravascular Imaging Studies Identifying Predictors of Cardiovascular Events

2.1. Underexpansion

2.2. Edge Dissection and Plaque at Stent Edge

2.3. Tissue or Thrombus Protrusion

2.4. Malapposition

3. Studies on Intravascular Imaging-Guided PCI: From Past to Present

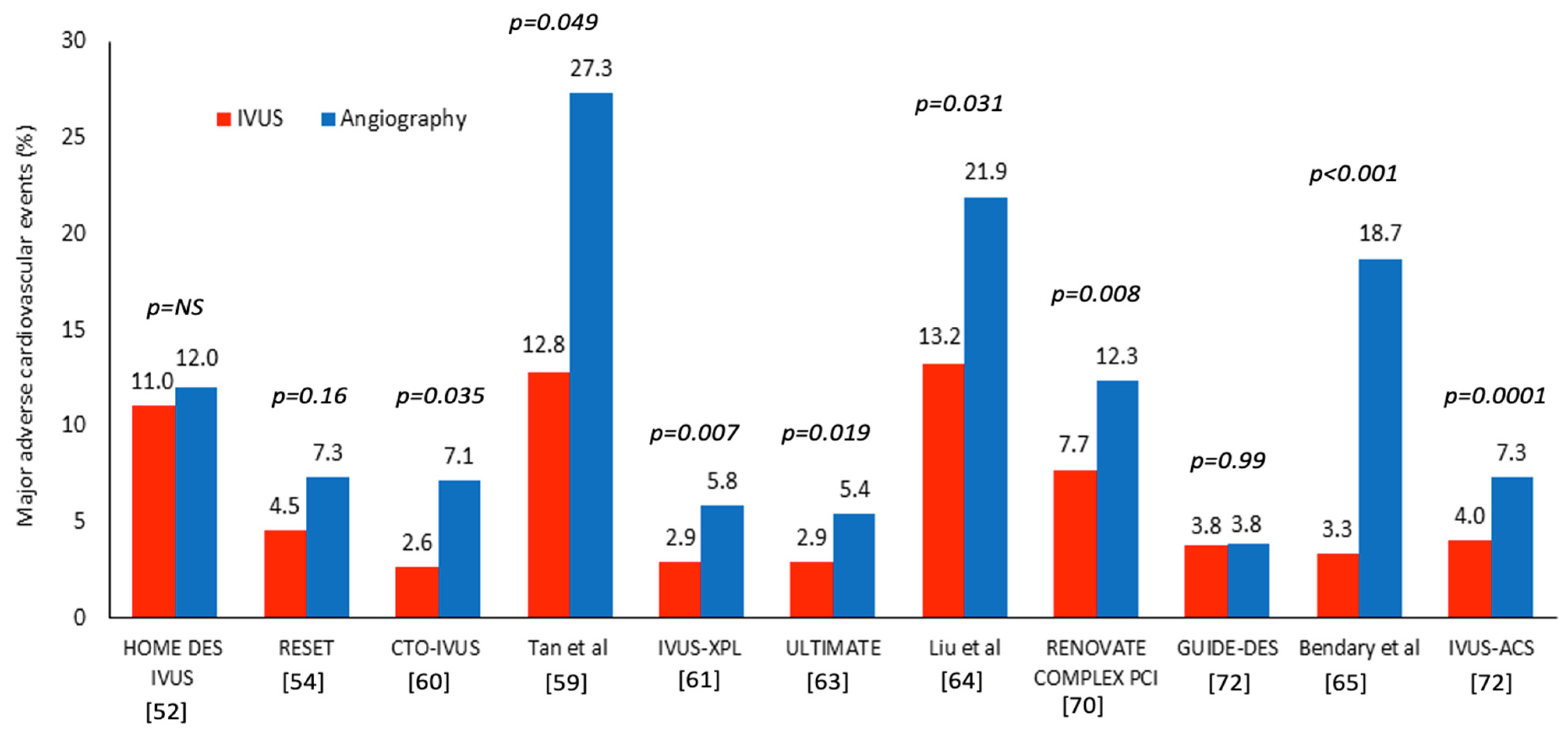

3.1. Evidence Supporting the Use of IVUS in the Guiding DES Implantation

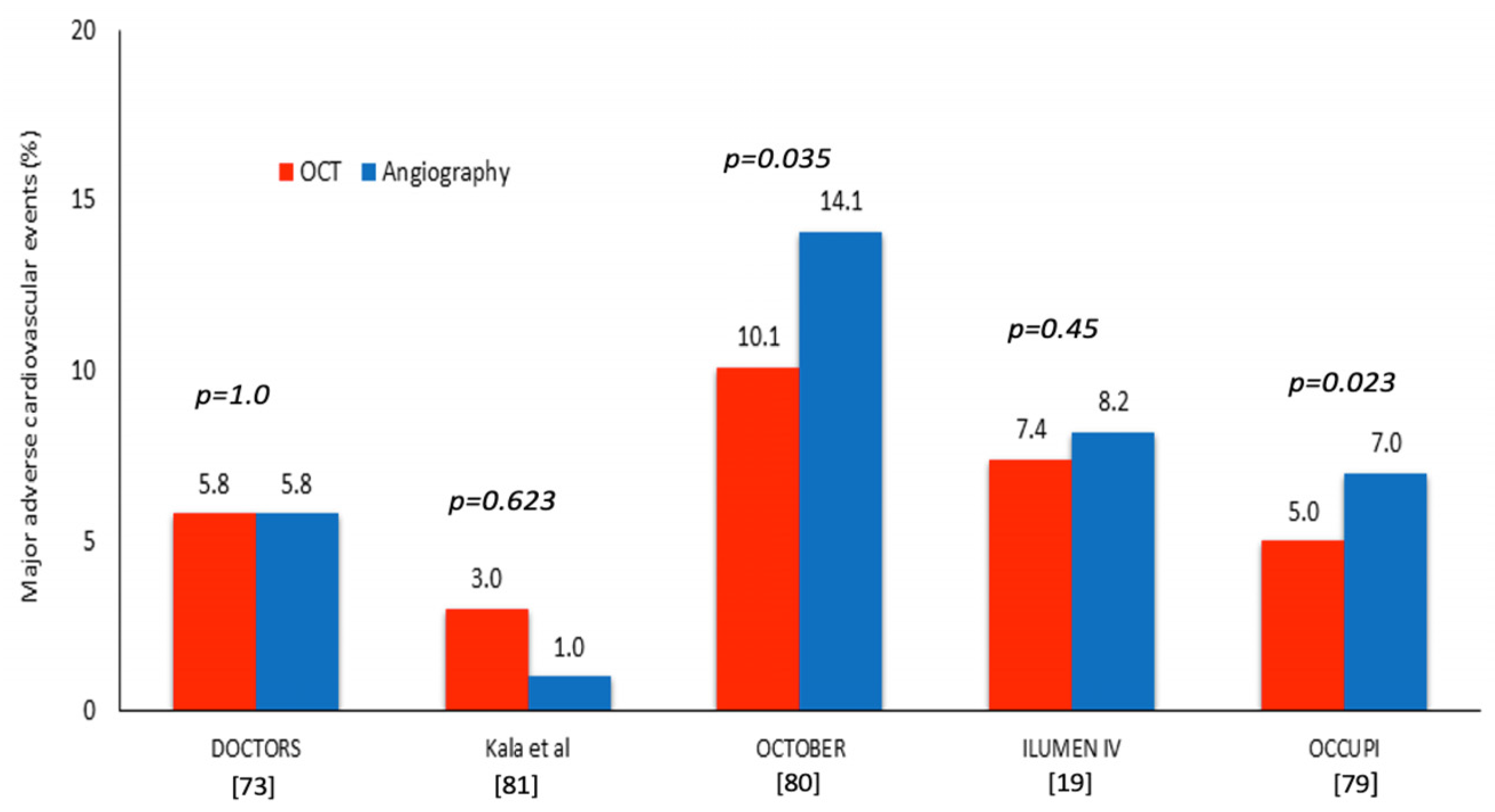

3.2. Evidence Supporting the Use of OCT in Guiding DES Implantation

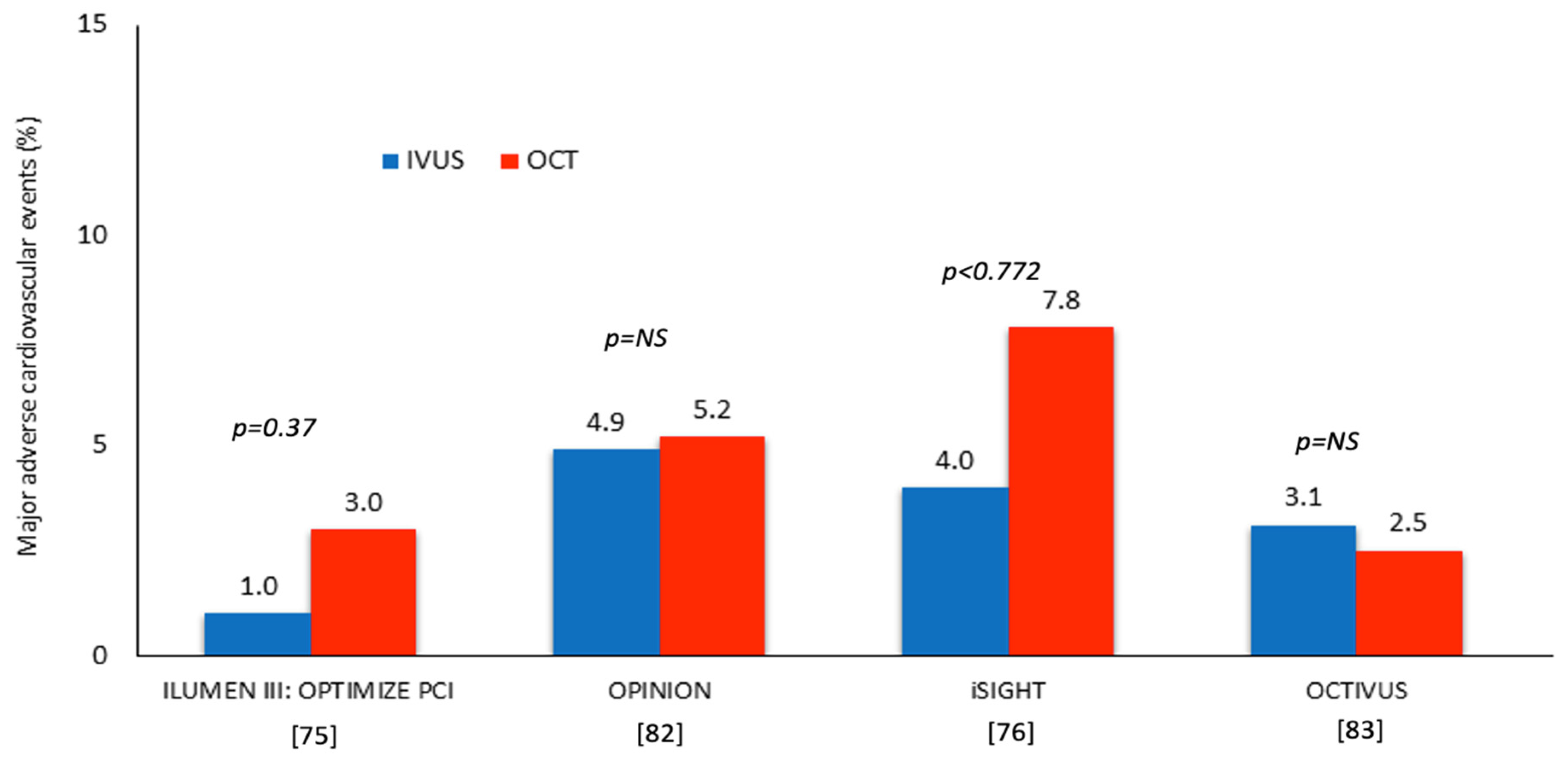

3.3. IVUS or OCT for Guiding PCI

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartorelli, A.L.; Potkin, B.N.; Almagor, Y.; Keren, G.; Roberts, W.C.; Leon, M.B. Plaque characterization of atherosclerotic coronary arteries by intravascular ultrasound. Echocardiography 1990, 7, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudra, H.; Blasini, R.; Regar, E.; Klauss, V.; Rieber, J.; Theisen, K. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of the balloon-expandable Palmaz-Schatz coronary stent. Coron. Artery Dis. 1993, 4, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourantas, C.V.; Tenekecioglu, E.; Radu, M.; Raber, L.; Serruys, P.W. State of the art: Role of intravascular imaging in the evolution of percutaneous coronary intervention—A 30-year review. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintz, G.S.; Pichard, A.D.; Kent, K.M.; Satler, L.F.; Popma, J.J.; Leon, M.B. Axial plaque redistribution as a mechanism of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 1996, 77, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintz, G.S.; Potkin, B.N.; Keren, G.; Satler, L.F.; Pichard, A.D.; Kent, K.M.; Popma, J.J.; Leon, M.B. Intravascular ultrasound evaluation of the effect of rotational atherectomy in obstructive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Circulation 1992, 86, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potkin, B.N.; Keren, G.; Mintz, G.S.; Douek, P.C.; Pichard, A.D.; Satler, L.F.; Kent, K.M.; Leon, M.B. Arterial responses to balloon coronary angioplasty: An intravascular ultrasound study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 20, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Kaburagi, S.; Tamura, T.; Yokoi, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Yokoi, H.; Hamasaki, N.; Nosaka, H.; Nobuyoshi, M.; Mintz, G.S.; et al. Remodeling of human coronary arteries undergoing coronary angioplasty or atherectomy. Circulation 1997, 96, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, G.S.; Popma, J.J.; Pichard, A.D.; Kent, K.M.; Satler, L.F.; Wong, C.; Hong, M.K.; Kovach, J.A.; Leon, M.B. Arterial remodeling after coronary angioplasty: A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 1996, 94, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haude, M.; Erbel, R.; Issa, H.; Straub, U.; Rupprecht, H.J.; Treese, N.; Meyer, J. Subacute thrombotic complications after intracoronary implantation of Palmaz-Schatz stents. Am. Heart J. 1993, 126, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Mintz, G.S.; Dussaillant, G.R.; Popma, J.J.; Pichard, A.D.; Satler, L.F.; Kent, K.M.; Griffin, J.; Leon, M.B. Patterns and mechanisms of in-stent restenosis. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 1996, 94, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uren, N.G.; Schwarzacher, S.P.; Metz, J.A.; Lee, D.P.; Honda, Y.; Yeung, A.C.; Fitzgerald, P.J.; Yock, P.G.; Investigators, P.R. Predictors and outcomes of stent thrombosis: An intravascular ultrasound registry. Eur. Heart J. 2002, 23, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.E.; Costa, M.A.; Abizaid, A.; Abizaid, A.S.; Feres, F.; Pinto, I.M.; Seixas, A.C.; Staico, R.; Mattos, L.A.; Sousa, A.G.; et al. Lack of neointimal proliferation after implantation of sirolimus-coated stents in human coronary arteries: A quantitative coronary angiography and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 2001, 103, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Ladich, E.; Nakazawa, G.; Eshtehardi, P.; Neidhart, M.; Vogel, R.; Togni, M.; Wenaweser, P.; Billinger, M.; Seiler, C.; et al. Correlation of intravascular ultrasound findings with histopathological analysis of thrombus aspirates in patients with very late drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Circulation 2009, 120, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Bourantas, C.; Serruys, P.W. New concepts in the design of drug-eluting coronary stents. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.J.; Ahn, J.M.; Song, H.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, D.W.; Yun, S.C.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, C.W.; et al. Comprehensive intravascular ultrasound assessment of stent area and its impact on restenosis and adverse cardiac events in 403 patients with unprotected left main disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, A.; Mintz, G.; Serruys, P.; Kappetein, A.; Kandzari, D.; Schampaert, E.; Van Boven, A.; Horkay, F.; Ungi, I.; Mansour, S.; et al. Impact of Final Minimal Stent Area by Ivus on 3-Year Outcome after Pci of Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: The Excel Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.K.; Mintz, G.S.; Lee, C.W.; Park, D.W.; Choi, B.R.; Park, K.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Cheong, S.S.; Song, J.K.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.G.; Kang, S.J.; Ahn, J.M.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, D.W.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, C.W.; Park, S.W.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of optimal stent area to prevent in-stent restenosis after zotarolimus-, everolimus-, and sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 83, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmesser, U.; Ali, Z.A.; Maehara, A.; Matsumura, M.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Guagliumi, G.; Price, M.J.; Hill, J.M.; Akasaka, T.; Prati, F.; et al. Optical coherence tomography predictors of clinical outcomes after stent implantation: The ILUMIEN IV trial. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4630–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Romagnoli, E.; Burzotta, F.; Limbruno, U.; Gatto, L.; La Manna, A.; Versaci, F.; Marco, V.; Di Vito, L.; Imola, F.; et al. Clinical Impact of OCT Findings During PCI: The CLI-OPCI II Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, T.; Joner, M.; Godschalk, T.C.; Malik, N.; Alfonso, F.; Xhepa, E.; De Cock, D.; Komukai, K.; Tada, T.; Cuesta, J.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Patients With Coronary Stent Thrombosis: A Report of the PRESTIGE Consortium (Prevention of Late Stent Thrombosis by an Interdisciplinary Global European Effort). Circulation 2017, 136, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniwaki, M.; Radu, M.D.; Zaugg, S.; Amabile, N.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Yamaji, K.; Jorgensen, E.; Kelbaek, H.; Pilgrim, T.; Caussin, C.; et al. Mechanisms of Very Late Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. Circulation 2016, 133, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souteyrand, G.; Amabile, N.; Mangin, L.; Chabin, X.; Meneveau, N.; Cayla, G.; Vanzetto, G.; Barnay, P.; Trouillet, C.; Rioufol, G.; et al. Mechanisms of stent thrombosis analysed by optical coherence tomography: Insights from the national PESTO French registry. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, L.; Mintz, G.S.; Koskinas, K.C.; Johnson, T.W.; Holm, N.R.; Onuma, Y.; Radu, M.D.; Joner, M.; Yu, B.; Jia, H.; et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: Guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3281–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Witzenbichler, B.; Maehara, A.; Lansky, A.J.; Guagliumi, G.; Brodie, B.; Kellett, M.A., Jr.; Dressler, O.; Parise, H.; Mehran, R.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound findings of early stent thrombosis after primary percutaneous intervention in acute myocardial infarction: A Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) substudy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, F.; Kodama, T.; Romagnoli, E.; Gatto, L.; Di Vito, L.; Ramazzotti, V.; Chisari, A.; Marco, V.; Cremonesi, A.; Parodi, G.; et al. Suboptimal stent deployment is associated with subacute stent thrombosis: Optical coherence tomography insights from a multicenter matched study. From the CLI Foundation investigators: The CLI-THRO study. Am. Heart J. 2015, 169, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Cho, Y.R.; Park, G.M.; Ahn, J.M.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, D.W.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, C.W.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound predictors for edge restenosis after newer generation drug-eluting stent implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Maehara, A.; Mintz, G.S.; Weissman, N.J.; Yu, A.; Wang, H.; Mandinov, L.; Popma, J.J.; Ellis, S.G.; Grube, E.; et al. An integrated TAXUS IV, V, and VI intravascular ultrasound analysis of the predictors of edge restenosis after bare metal or paclitaxel-eluting stents. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, Y.; Kubo, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Shiono, Y.; Shimamura, K.; Katayama, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Aoki, H.; Taruya, A.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Predictors for Edge Restenosis After Everolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e004231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Romagnoli, E.; Biccirè, F.G.; Burzotta, F.; La Manna, A.; Budassi, S.; Ramazzotti, V.; Albertucci, M.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Sticchi, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes of suboptimal stent deployment as assessed by optical coherence tomography: Long-term results of the CLI-OPCI registry. EuroIntervention 2022, 18, e150–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Muramatsu, T.; Nakatani, S.; Lee, I.S.; Holm, N.R.; Thuesen, L.; van Geuns, R.J.; van der Ent, M.; Borovicanin, V.; Paunovic, D.; et al. Serial optical frequency domain imaging in STEMI patients: The follow-up report of TROFI study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 15, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Romagnoli, E.; Gatto, L.; La Manna, A.; Burzotta, F.; Limbruno, U.; Versaci, F.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Di Giorgio, A.; Marco, V.; et al. Clinical Impact of Suboptimal Stenting and Residual Intrastent Plaque/Thrombus Protrusion in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: The CLI-OPCI ACS Substudy (Centro per la Lotta Contro L’Infarto-Optimization of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome). Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e003726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, T.; Uemura, S.; Park, S.J.; Jang, Y.; Lee, S.; Cho, J.M.; Kim, S.J.; Vergallo, R.; Minami, Y.; Ong, D.S.; et al. Incidence and Clinical Significance of Poststent Optical Coherence Tomography Findings: One-Year Follow-Up Study From a Multicenter Registry. Circulation 2015, 132, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.J.; Jeong, M.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Song, J.A.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, K.H.; Yamanaka, F.; Lee, M.G.; Park, K.H.; Sim, D.S.; et al. Impact of tissue prolapse after stent implantation on short- and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction: An intravascular ultrasound analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyodo, A.; Watanabe, M.; Okamura, A.; Iwai, S.; Sakagami, A.; Nogi, K.; Kamon, D.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ueda, T.; Soeda, T.; et al. Post-Stent Optical Coherence Tomography Findings at Index Percutaneous Coronary Intervention—Characteristics Related to Subsequent Stent Thrombosis. Circ. J. 2021, 85, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.H.; Mintz, G.S.; Mandinov, L.; Yu, A.; Ellis, S.G.; Grube, E.; Dawkins, K.D.; Ormiston, J.; Turco, M.A.; Stone, G.W.; et al. Long-term impact of routinely detected early and late incomplete stent apposition: An integrated intravascular ultrasound analysis of the TAXUS IV, V, and VI and TAXUS ATLAS workhorse, long lesion, and direct stent studies. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Kachel, M.; Kim, J.S.; Guagliumi, G.; Kim, C.; Kim, I.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, O.H.; Byun, Y.S.; Kim, B.O.; et al. Clinical Implications of Poststent Optical Coherence Tomographic Findings: Severe Malapposition and Cardiac Events. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Wenaweser, P.; Togni, M.; Billinger, M.; Morger, C.; Seiler, C.; Vogel, R.; Hess, O.; Meier, B.; Windecker, S. Incomplete stent apposition and very late stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation 2007, 115, 2426–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Ahn, J.M.; Mintz, G.S.; Hur, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Cho, J.M.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, J.W.; Hong, Y.J.; et al. Characteristics of Earlier Versus Delayed Presentation of Very Late Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis: An Optical Coherence Tomographic Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, G.; La Manna, A.; Di Vito, L.; Valgimigli, M.; Fineschi, M.; Bellandi, B.; Niccoli, G.; Giusti, B.; Valenti, R.; Cremonesi, A.; et al. Stent-related defects in patients presenting with stent thrombosis: Differences at optical coherence tomography between subacute and late/very late thrombosis in the Mechanism Of Stent Thrombosis (MOST) study. EuroIntervention 2013, 9, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliumi, G.; Sirbu, V.; Musumeci, G.; Gerber, R.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Ikejima, H.; Ladich, E.; Lortkipanidze, N.; Matiashvili, A.; Valsecchi, O.; et al. Examination of the in vivo mechanisms of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis: Findings from optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 5, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Steinberg, D.H.; Sushinsky, S.J.; Okabe, T.; Pinto Slottow, T.L.; Kaneshige, K.; Xue, Z.; Satler, L.F.; Kent, K.M.; Suddath, W.O.; et al. The potential clinical utility of intravascular ultrasound guidance in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 1851–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, S.H.; Kang, S.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, J.M.; Park, D.W.; Lee, S.W.; Yun, S.C.; Lee, C.W.; Park, S.W.; Park, S.J. Impact of intravascular ultrasound-guided percutaneous coronary intervention on long-term clinical outcomes in a real world population. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 81, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.W.; Kang, S.H.; Yang, H.M.; Lee, H.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Cho, Y.S.; Youn, T.J.; Koo, B.K.; Chae, I.H.; Kim, H.S. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in routine percutaneous coronary intervention for conventional lesions: Data from the EXCELLENT trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.; Jeong, M.H.; Chakraborty, R.; Ahn, Y.; Sim, D.S.; Park, K.; Hong, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, M.C.; et al. Role of intravascular ultrasound in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claessen, B.E.; Mehran, R.; Mintz, G.S.; Weisz, G.; Leon, M.B.; Dogan, O.; de Ribamar Costa, J., Jr.; Stone, G.W.; Apostolidou, I.; Morales, A.; et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound imaging on early and late clinical outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzenbichler, B.; Maehara, A.; Weisz, G.; Neumann, F.-J.; Rinaldi, M.J.; Metzger, D.C.; Henry, T.D.; Cox, D.A.; Duffy, P.L.; Brodie, B.R.; et al. Relationship Between Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance and Clinical Outcomes After Drug-Eluting Stents: The Assessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy with Drug-Eluting Stents (ADAPT-DES) Study. Circulation 2014, 129, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, A.; Mintz, G.S.; Witzenbichler, B.; Weisz, G.; Neumann, F.J.; Rinaldi, M.J.; Metzger, D.C.; Henry, T.D.; Cox, D.A.; Duffy, P.L.; et al. Relationship Between Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance and Clinical Outcomes After Drug-Eluting Stents: Two-Year Follow-Up of the ADAPT-DES Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, e006243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Ye, F.; Zhang, J.J.; Tian, N.L.; Liu, Z.Z.; Santoso, T.; Zhou, Y.J.; Jiang, T.M.; Wen, S.Y.; Kwan, T.W. Intravascular ultrasound-guided systematic two-stent techniques for coronary bifurcation lesions and reduced late stent thrombosis. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 81, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Kang, S.J.; Park, D.W.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, C.W.; Hong, M.K.; Cheong, S.S.; Kim, J.J.; Park, S.W.; et al. Long-term outcomes of intravascular ultrasound-guided stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Hong, M.K.; Ko, Y.G.; Choi, D.; Yoon, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Hahn, J.Y.; Gwon, H.C.; Jeong, M.H.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term clinical outcomes in patients treated with drug-eluting stent for bifurcation lesions: Data from a Korean multicenter bifurcation registry. Am. Heart J. 2011, 161, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakabcin, J.; Spacek, R.; Bystron, M.; Kvasnak, M.; Jager, J.; Veselka, J.; Kala, P.; Cervinka, P. Long-term health outcome and mortality evaluation after invasive coronary treatment using drug eluting stents with or without the IVUS guidance. Randomized control trial. HOME DES IVUS. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 75, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieffo, A.; Latib, A.; Caussin, C.; Presbitero, P.; Galli, S.; Menozzi, A.; Varbella, F.; Mauri, F.; Valgimigli, M.; Arampatzis, C.; et al. A prospective, randomized trial of intravascular-ultrasound guided compared to angiography guided stent implantation in complex coronary lesions: The AVIO trial. Am. Heart J. 2013, 165, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kang, T.S.; Mintz, G.S.; Park, B.E.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, B.K.; Ko, Y.G.; Choi, D.; Jang, Y.; Hong, M.K. Randomized comparison of clinical outcomes between intravascular ultrasound and angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation for long coronary artery stenoses. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, N.L.; Gami, S.K.; Ye, F.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, Z.Z.; Lin, S.; Ge, Z.; Shan, S.J.; You, W.; Chen, L.; et al. Angiographic and clinical comparisons of intravascular ultrasound- versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation for patients with chronic total occlusion lesions: Two-year results from a randomised AIR-CTO study. EuroIntervention 2015, 10, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.M.; Han, S.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, W.S.; Jang, J.Y.; Kwon, C.H.; Park, G.M.; Cho, Y.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, W.J.; et al. Differential prognostic effect of intravascular ultrasound use according to implanted stent length. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre Hernandez, J.M.; Baz Alonso, J.A.; Gomez Hospital, J.A.; Alfonso Manterola, F.; Garcia Camarero, T.; Gimeno de Carlos, F.; Roura Ferrer, G.; Recalde, A.S.; Martinez-Luengas, I.L.; Gomez Lara, J.; et al. Clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary disease: Pooled analysis at the patient-level of 4 registries. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.F.; Kan, J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Tian, N.L.; Ye, F.; Ge, Z.; Xiao, P.X.; Chen, F.; Mintz, G.; et al. Comparison of one-year clinical outcomes between intravascular ultrasound-guided versus angiography-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents for left main lesions: A single-center analysis of a 1,016-patient cohort. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2014, 8, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Intravascular ultrasound-guided unprotected left main coronary artery stenting in the elderly. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.K.; Shin, D.H.; Hong, M.K.; Park, H.S.; Rha, S.W.; Mintz, G.S.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.Y.; et al. Clinical Impact of Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention With Zotarolimus-Eluting Versus Biolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation: Randomized Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, e002592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Kim, B.K.; Shin, D.H.; Nam, C.M.; Kim, J.S.; Ko, Y.G.; Choi, D.; Kang, T.S.; Kang, W.C.; Her, A.Y.; et al. Effect of Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided vs Angiography-Guided Everolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation: The IVUS-XPL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.J.; Mintz, G.S.; Ahn, C.M.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, B.K.; Ko, Y.G.; Kang, T.S.; Kang, W.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Hur, S.H.; et al. Effect of Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: 5-Year Follow-Up of the IVUS-XPL Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Kan, J.; Ge, Z.; Han, L.; Lu, S.; Tian, N.; Lin, S.; Lu, Q.; Wu, X.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound Versus Angiography-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3126–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Yang, Z.M.; Liu, X.K.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.Q.; Han, Q.L.; Sun, J.H. Intravascular ultrasound-guided drug-eluting stent implantation for patients with unprotected left main coronary artery lesions: A single-center randomized trial. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2019, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendary, A.; Elsaed, A.; Tabl, M.A.; Ahmed ElRabat, K.; Zarif, B. Intravascular ultrasound-guided percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with unprotected left main coronary artery lesions. Coron. Artery Dis. 2024, 35, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, T.; Johnson, T.; Anderson, R.; Gallagher, S.; Sirker, A.; Ludman, P.; de Belder, M.; Copt, S.; Oldroyd, K.; Banning, A.; et al. Intravascular Imaging and 12-Month Mortality After Unprotected Left Main Stem PCI: An Analysis From the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society Database. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andell, P.; Karlsson, S.; Mohammad, M.A.; Gotberg, M.; James, S.; Jensen, J.; Frobert, O.; Angeras, O.; Nilsson, J.; Omerovic, E.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance Is Associated With Better Outcome in Patients Undergoing Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery Stenting Compared With Angiography Guidance Alone. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, e004813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladwiniec, A.; Walsh, S.J.; Holm, N.R.; Hanratty, C.G.; Makikallio, T.; Kellerth, T.; Hildick-Smith, D.; Mogensen, L.J.H.; Hartikainen, J.; Menown, I.B.A.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound to guide left main stem intervention: A NOBLE trial substudy. EuroIntervention 2020, 16, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, B.; de la Torre Hernandez, J.M.; Lanocha, M.; Ielasi, A.; Giannini, F.; Campo, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Latini, R.A.; Krestianinov, O.; Alfonso, F.; et al. Optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound or angiography guidance for distal left main coronary stenting. The ROCK cohort II study. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Choi, K.H.; Song, Y.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Yun, K.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, C.J.; et al. Intravascular Imaging–Guided or Angiography-Guided Complex PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ge, Z.; Kan, J.; Anjum, M.; Xie, P.; Chen, X.; Khan, H.S.; Guo, X.; Saghir, T.; Chen, J.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided versus angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes (IVUS-ACS): A two-stage, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 1855–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, Y.w.; Lee, J.-Y.; Oh, S.-J.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, S.-W.; et al. Quantitative Coronary Angiography vs Intravascular Ultrasonography to Guide Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneveau, N.; Souteyrand, G.; Motreff, P.; Caussin, C.; Amabile, N.; Ohlmann, P.; Morel, O.; Lefrancois, Y.; Descotes-Genon, V.; Silvain, J.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography to Optimize Results of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome: Results of the Multicenter, Randomized DOCTORS Study (Does Optical Coherence Tomography Optimize Results of Stenting). Circulation 2016, 134, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakl, M.; Cervinka, P.; Kanovsky, J.; Kala, P.; Poloczek, M.; Cervinkova, M.; Bezerra, H.G.; Valenta, Z.; Costa, M.A. Randomized comparison of 9-month stent strut coverage of biolimus and everolimus drug-eluting stents assessed by optical coherence tomography in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Long-term (5-years) clinical follow-up (ROBUST trial). Cardiol. J. 2023, 30, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Maehara, A.; Genereux, P.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Nazif, T.M.; Guagliumi, G.; Meraj, P.M.; Alfonso, F.; Samady, H.; et al. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamié, D.; Costa, J.R.; Damiani, L.P.; Siqueira, D.; Braga, S.; Costa, R.; Seligman, H.; Brito, F.; Barreto, G.; Staico, R.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Versus Intravascular Ultrasound and Angiography to Guide Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e009452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Rathod, K.S.; Koganti, S.; Hamshere, S.; Astroulakis, Z.; Lim, P.; Sirker, A.; O’Mahony, C.; Jain, A.K.; Knight, C.J.; et al. Angiography Alone Versus Angiography Plus Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Outcomes From the Pan-London PCI Cohort. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Landmesser, U.; Maehara, A.; Matsumura, M.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Guagliumi, G.; Price, M.J.; Hill, J.M.; Akasaka, T.; Prati, F.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography–Guided versus Angiography-Guided PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Cho, D.-K.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.M.; Hur, S.-H.; Heo, J.H.; Jang, J.-Y.; et al. Optical coherence tomography-guided versus angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with complex lesions (OCCUPI): An investigator-initiated, multicentre, randomised, open-label, superiority trial in South Korea. Lancet 2024, 404, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, N.R.; Andreasen, L.N.; Neghabat, O.; Laanmets, P.; Kumsars, I.; Bennett, J.; Olsen, N.T.; Odenstedt, J.; Hoffmann, P.; Dens, J.; et al. OCT or Angiography Guidance for PCI in Complex Bifurcation Lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, P.; Cervinka, P.; Jakl, M.; Kanovsky, J.; Kupec, A.; Spacek, R.; Kvasnak, M.; Poloczek, M.; Cervinkova, M.; Bezerra, H.; et al. OCT guidance during stent implantation in primary PCI: A randomized multicenter study with nine months of optical coherence tomography follow-up. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 250, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Shinke, T.; Okamura, T.; Hibi, K.; Nakazawa, G.; Morino, Y.; Shite, J.; Fusazaki, T.; Otake, H.; Kozuma, K.; et al. Optical frequency domain imaging vs. intravascular ultrasound in percutaneous coronary intervention (OPINION trial): One-year angiographic and clinical results. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 3139–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-Y.; Ahn, J.-M.; Yun, S.-C.; Hur, S.-H.; Cho, Y.-K.; Lee, C.H.; Hong, S.J.; Lim, S.; Kim, S.-W.; Won, H.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography–Guided or Intravascular Ultrasound–Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The OCTIVUS Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2023, 148, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Christiansen, E.H.; Ali, Z.A.; Andreasen, L.N.; Maehara, A.; Ahmad, Y.; Landmesser, U.; Holm, N.R. Intravascular imaging-guided coronary drug-eluting stent implantation: An updated network meta-analysis. Lancet 2024, 403, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Laudani, C.; Occhipinti, G.; Spagnolo, M.; Greco, A.; Rochira, C.; Agnello, F.; Landolina, D.; Mauro, M.S.; Finocchiaro, S.; et al. Coronary Angiography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Optical Coherence Tomography for Guiding of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2024, 149, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Agarwal, S.; Arshad, H.B.; Akbar, U.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Arora, S.; Baber, U.; Goel, S.S.; Kleiman, N.S.; Shah, A.R. Intravascular imaging guided versus coronary angiography guided percutaneous coronary intervention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2023, 383, e077848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Bujas-Bobanovic, M.; Diaz, R.; Fazio, S.; Fras, Z.; Goodman, S.G.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Transiently achieved very low LDL-cholesterol levels by statin and alirocumab after acute coronary syndrome are associated with cardiovascular risk reduction: The ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994, 344, 1383–1389. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Rader, D.J.; Rouleau, J.L.; Belder, R.; Joyal, S.V.; Hill, K.A.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Skene, A.M.; et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Hong, D.; Singh, M.; Lee, S.H.; Sakai, K.; Dakroub, A.; Malik, S.; Maehara, A.; Shlofmitz, E.; Stone, G.W.; et al. Intravascular imaging-guided percutaneous coronary intervention for heavily calcified coronary lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 40, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Parasa, R.; Ramasamy, A.; Makariou, N.; Foin, N.; Prati, F.; Lansky, A.; Mathur, A.; Baumbach, A.; Bourantas, C.V. Computerized technologies informing cardiac catheterization and guiding coronary intervention. Am. Heart J. 2021, 240, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Dai, J.; He, L.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Weng, Z.; Feng, X.; et al. EROSION III: A Multicenter RCT of OCT-Guided Reperfusion in STEMI With Early Infarct Artery Patency. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.F.; Ge, Z.; Kong, X.Q.; Chen, X.; Han, L.; Qian, X.S.; Zuo, G.F.; Wang, Z.M.; Wang, J.; Song, J.X.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound vs Angiography-Guided Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty: The ULTIMATE Ⅲ Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Hu, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Weng, Z.; Qin, Y.; Feng, X.; Yu, H.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. Five-year follow-up of OCT-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e937–e947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Studied Groups | Number of Patients | Follow-Up (Months) | Lesion Type | Endpoints | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOME DES IVUS [52] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 210 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 18 | Complex lesions type B2 and C, LMS or proximal LAD disease, small vessels (<2.5 mm), long lesions (>20 mm), ISR, patients with an ACS or ID-DM | - MACE including death, MI, TLR - ST | - There was no significant difference between groups in the incidence of MACE (11% vs. 12%; p = NS) or stent thrombosis (3.8 vs. 5.7%; p = NS) |

| AVIO [53] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 284 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 24 | Long lesions (>28 mm), CTOs, bifurcation lesions, small vessels (≤2.5 mm) and patients requiring four or more stents | - Post-procedural in-lesion MLD - MACE including any MI, cardiac death, TLR and TVR | - IVUS guidance was associated with a larger minimal lumen diameter (2.70 ± 0.46 mm vs. 2.51 ± 0.46 mm; p = 0.0002) than angiography-guided PCI - There was no difference in MACE at 24-month follow-up (7.0% vs. 8.5%, p = NS) |

| RESET [54] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 543 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | De novo lesion requiring a stent ≥ 28 mm in length in a vessel with a distal reference diameter ≥ 2.5 mm | - MACE, including cardiovascular death, MI, ST and TVR | - There was no significant difference in the incidence of MACE, including CD, MI, ST, or TVR, between the IVUS-guided arm (4.5%) and the angiography-guided arm (7.3%, p = 0.16) |

| CTO-IVUS [60] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided revascularization | 402 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | CTO lesions | - Cardiac death - Secondary: MACE defined as the composite of cardiac death, MI, or TVR | - There was no difference in the incidence of cardiac death between groups (0% versus 1.0%; p = 0.16) - MACE rate was lower in patients having IVUS guided PCI than the angiography-guided group (2.6% vs. 7.1%; p = 0.035) |

| AIR-CTO [55] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 230 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 24 | CTO lesions that had been successfully recanalized | - In-stent LLL - Secondary: All-cause death, cardiac death, MI, ISR, TLR and TVR | - The use of IVUS was associated with a smaller reduced LLL (0.28 ± 0.48 mm vs. 0.46 ± 0.68 mm, p = 0.025) than angiography-guided PCI - There were no significant differences in the incidence of MACE in the two groups (18.3% vs. 22.6%, p = 0.513) - The event rate in the two groups for the secondary endpoints was similar apart from the incidence of ST that was lower in the IVUS arm (0.9% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.043) |

| Tan et al. [59] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 123 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 24 | LMS disease was defined as ≥50% stenosis by visual assessment | - MACE, was defined as death, non-fatal MI, and TLR-Safety endpoint was ST | - The overall MACE rate was lower in the IVUS-guided group than in the control group (12.8% vs. 27.3%, p = 0.049) - The ST rate was similar in the two groups (1.6% vs. 3.2%, p = 0.568) |

| IVUS-XPL [61] | IVUS vs. angiography | 1400 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | Long lesions ≥ 28 mm | - MACE, including cardiac death, TV-MI, or ID-TLR | - The MACE rate was lower in the IVUS arm compared to the angiography arm (2.9% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.007), mainly due a reduced ID-TLR (2.5% vs. 5.0%, p = 0.02) |

| ULTIMATE [63] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 1448 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | All lesions deemed suitable for PCI | - Primary: TVF, including CD, TV-MI, and clinically driven TVR - Secondary: All-cause death, MI, TLR, ISR, stroke, and each individual component of the primary endpoint | - TVF occurred more often in the angiography than the IVUS-guided groups (5.4% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.019) - There was no difference in the outcomes for the secondary endpoint analyses |

| Liu et al. [64] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided PCI | 336 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | LMS lesions planned PCI | - Primary: MACE, including CD, MI, and TVR - Safety endpoint: the incidence of ST | - IVUS use was associated with a lower MACE rate than angiography-guided PCI (13.2% vs. 21.9%, p = 0.031) -The incidence of ST was similar in the two groups |

| RENOVATECOMPLEX-PCI [70] | Intravascular imaging- (IVUS or OCT) vs. angiography-guided PCI | 1639 patients randomized at 2:1 ratio in the intravascular imaging and angiography-guided revascularization | 25 | True bifurcation lesions with side branches ≥ 2.5 mm, CTO’s, LMS, long lesions ≥ 38 mm, multivessel PCI, ≥3 stents, ISR, severe calcification, or ostial lesions | - Primary: TVF, defined as the composite of CD, TV-MI, or clinically driven TVR - Secondary: The individual components of the primary endpoint, TVF without procedure-related MI, a composite of TV-MI or CD, and definite ST | - TVF occurred in 7.7% of the patients in the intravascular imaging group and in 12.3% in the angiography group (p = 0.008) - The incidence of TVF without procedure-related MI was lower in the intravascular imaging group than in the angiography group (5.1% vs. 8.7%) |

| GUIDE-DES [72] | QCA vs. IVUS-guided revascularization | 1528 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | Any obstructive lesion listed for PCI | - Primary: TLF, defined as a composite of CD, TV-MI, or ID-TVR Secondary: All-cause death, MI, definite or probable ST, stroke, TLR and any revascularisation | - The incidence of TLF was similar in the QCA and IVUS-guided group (3.81% vs. 3.80%) (p = 0.99). - Secondary endpoint events were infrequent and similar in both groups |

| Bendary et al. [65] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided revascularization | 181 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | LMS lesions scheduled for DES implantation | - MACE, which encompasses CD, MI and TVR -Safety endpoint: ST | - Patients who underwent IVUS demonstrated a significantly lower MACE (3.3% vs. 18.7%, p < 0.001) than those who underwent the conventional method - There was no difference in MI, TVR, ST or in-hospital mortality rates between the groups (p > 0.05 for all) |

| IVUS-ACS [71] | IVUS vs. angiography-guided revascularization | 3504 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | Any culprit lesion in patients with an ACS treated with PCI using DES | - Primary: TVF, a composite of CD, TV-MI, or clinically driven TVR - Secondary: The individual components of the primary endpoint, TVF without procedural MI, TLR, bleeding and ST | - The TVF at 1 year occurred more often in the angiography than the IVUS arm (7.3% vs. 4.0%, p = 0·0001) - The incidence of TVF without procedural MI was also lower in the IVUS group (5.1% vs. 2.2%, p < 0·0001) |

| Study | Studied Groups | Number of Patients | Follow-Up (Months) | Lesion Type | Endpoints | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOCTORS [73] | OCT vs. Angiography-guided PCI | 240 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 6 | Any lesion suitable for PCI | - Post-procedural FFR - Secondary: procedural complications | - OCT-guided PCI led to higher post-PCI FFR than angiography (0.94 ± 0.04 vs. 0.92 ± 0.05, p = 0.005) - There was no difference in the procedural complications between groups |

| Kala et al. [81] | OCT vs. Angiography-guided PCI | 201 patients randomized at ~1:1 ratio | 9 | Culprit lesions in patients with a STEMI and reference diameter: 2.5–3.75 mm | - Primary: MACE; including death, MI and TLR - Secondary: In-segment area stenosis post PCI | - The MACE rate was similar in the two groups (3% vs. 1%, p = 0.623) - The in-segment area of stenosis was smaller in the OCT arm (6% vs. 18%, p = 0.0002) |

| OCTOBER [80] | OCT vs. Angiography-guided PCI | 1201 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 24 | Bifurcation lesions with ≥50% stenosis in both the main (≥2.75 mm reference diameter) and side branch (≥2.5 mm reference diameter) | - Primary: MACE, defined as CD, TLMI, or ID-TLR - Secondary: CD, TLMI, TLR, a bifurcation lesion–oriented composite endpoint of CD, TLMI; TLR and a patient-oriented composite endpoint of death from any cause, MI, any coronary revascularization, or stroke | - MACE occurred in 10.1% in the OCT and in 14.1% in the angiography-guided PCI (p = 0.035) - There was no statistically significant difference in the outcomes for the secondary endpoints |

| ILUMEN IV [19] | OCT- vs. Angiography-guided PCI | 2487 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 24 | Patients with diabetes and high-risk lesions including lesions causing a MI, long or multiple lesions (>28 mm stent), bifurcations needing two stents, severe calcification, CTOs and diffuse/multifocal ISR | - Primary imaging: MSA post PCI assessed by OCT - Primary clinical: TVF, defined as CD, TV-MI, or ID-TVR - The major secondary endpoint was target-vessel failure, excluding periprocedural myocardial infarction | - The MSA post PCI was larger in the OCT than the angiography-guided group (5.72 ± 2.04 mm2 vs. 5.36 ± 1.87 mm2, p < 0.001) - The TVF rate was similar in the two groups (7.4% in the OCT and 8.2% in the angiography arm, p = 0.45) |

| OCCUPI [79] | OCT vs. Angiography-guided-PCI | 1604 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | Culprit lesions in ACS, CTO, long lesions (≥28 mm), calcified, bifurcation lesions, LMS, small vessels (<2.5 mm), visible thrombus, stent thrombosis, ISR, or bypass graft lesions | - Primary: MACE, a composite of CD, MI, ST, or ID-TVR Secondary: Any revascularisation, TLR, periprocedural MI, stroke, bleeding events, rate of stent optimization confirmed by post-stenting OCT and CIN | - The primary endpoint occurred in 5% in the OCT and in 7% in the angiography-guided group (p = 0·023) - Any revascularization rate was smaller in the OCT group (6% vs. 2% p = 0.0009). There was no significant difference between groups for the other secondary endpoints |

| Study | Studied Groups | Number of Patients | Follow-Up (Months) | Lesion Type | Endpoints | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILUMEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI [75] | IVUS vs. OCT vs. Angiography | 450 patients randomized at 1:1:1 ratio | 12 | De novo lesions with a reference vessel diameter 2.25–3.50 mm and length < 40 mm | - Primary efficacy endpoint: post-PCI MSA - Primary safety endpoint: procedural MACE | - The MSA was comparable in the three groups (5.79 mm2 in the OCT, 5.89 mm2 in the IVUS, and 5.49 mm2 in the angiography arm) - There were no differences in procedural MACE in the three groups (p = 0.37) |

| OPINION [82] | IVUS vs. OCT-guided revascularization | 829 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | De novo lesions with diameter ≥ 2.5 mm listed for PCI | - Primary: TVF, defined as a composite of CD, TVR-MI and ID-TVR - Secondary: CD, MI, TVR-MI, ID-TVR and ID-TLR, MACE including CD, MI, or ID-TLR, ST, RS, stroke and CIN | - The TVF rate was similar in the two groups (5.2% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.042 for non-inferiority) - There was no difference between groups for all the secondary endpoints |

| iSIGHT [76] | IVUS vs. OCT vs. Angiography-guided PCI | 156 patients randomized at 1:1:1 ratio | 12 | De novo lesions with a reference between 2.25 and 4.0 mm | Primary: Stent expansion rate in the IVUS and OCT groups Secondary endpoint: Stent expansion in the three groups | - Stent expansion was similar in the OCT and IVUS groups (98.01 ± 16.14% vs. 91.69 ± 15.75%, pnon-inferiority < 0.001) - Patients undergoing OCT-guided PCI had a higher stent expansion rate than those listed for angiography-guided PCI (90.53 ± 14.84%, p = 0.041), but there was no difference between IVUS and angiography-guided groups (p = 0.067) |

| OCTIVUS [83] | IVUS vs. OCT-guided PCI | 2008 patients randomized at 1:1 ratio | 12 | The various types of significant coronary artery lesions (multivessel, left main vessel, bifurcations, extensive long coronary artery lesions) except for ST-segment elevation MI lesions | - Primary: TVF, defined as CD, TV-MI, or ID-TVR - Secondary: individual components of the primary endpoint, TLF, ST, stroke, repeat PCI, any rehospitalisation, bleeding, CIN, procedural complications and angiographic and imaging device success | - The primary endpoint had occurred in 2.5% in the OCT and in 3.1% in the IVUS-guided PCI groups (pnon-inferiority < 0.001) - There was no difference between IVUS and OCT guided revascularization in all the secondary endpoints |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeren, G.; Bakır, E.O.; Tufaro, V.; Özkaya, A.N.; Zhou, T.; Kyriakou, S.; Lee, J.-G.; Onuma, Y.; Serruys, P.W.; Bourantas, C.V. Intravascular Imaging for Facilitated Coronary Interventions in DES Era. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010038

Zeren G, Bakır EO, Tufaro V, Özkaya AN, Zhou T, Kyriakou S, Lee J-G, Onuma Y, Serruys PW, Bourantas CV. Intravascular Imaging for Facilitated Coronary Interventions in DES Era. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeren, Gönül, Eren Ozan Bakır, Vincenzo Tufaro, Ayşe Nur Özkaya, Tingquan Zhou, Sotiris Kyriakou, Jae-Geun Lee, Yoshinobu Onuma, Patrick W. Serruys, and Christos V. Bourantas. 2026. "Intravascular Imaging for Facilitated Coronary Interventions in DES Era" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010038

APA StyleZeren, G., Bakır, E. O., Tufaro, V., Özkaya, A. N., Zhou, T., Kyriakou, S., Lee, J.-G., Onuma, Y., Serruys, P. W., & Bourantas, C. V. (2026). Intravascular Imaging for Facilitated Coronary Interventions in DES Era. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010038