How to Use Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cardiotoxicity—Types and Definitions

3. Role of CVMI in Baseline Risk Stratification and Surveillance in Patients Undergoing Potentially Cardiotoxic Cancer Treatment

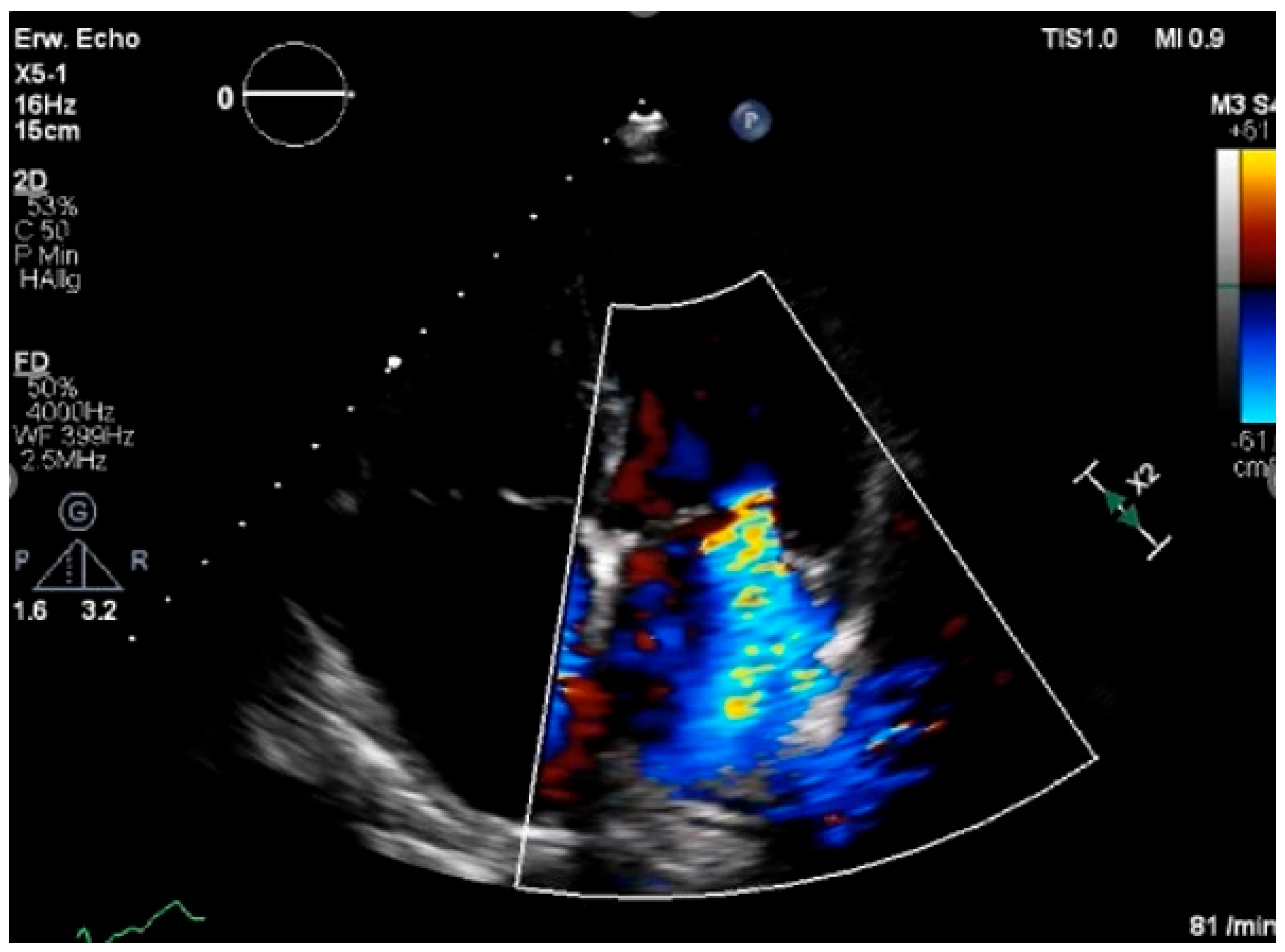

3.1. Echocardiography

3.1.1. Baseline Assessment

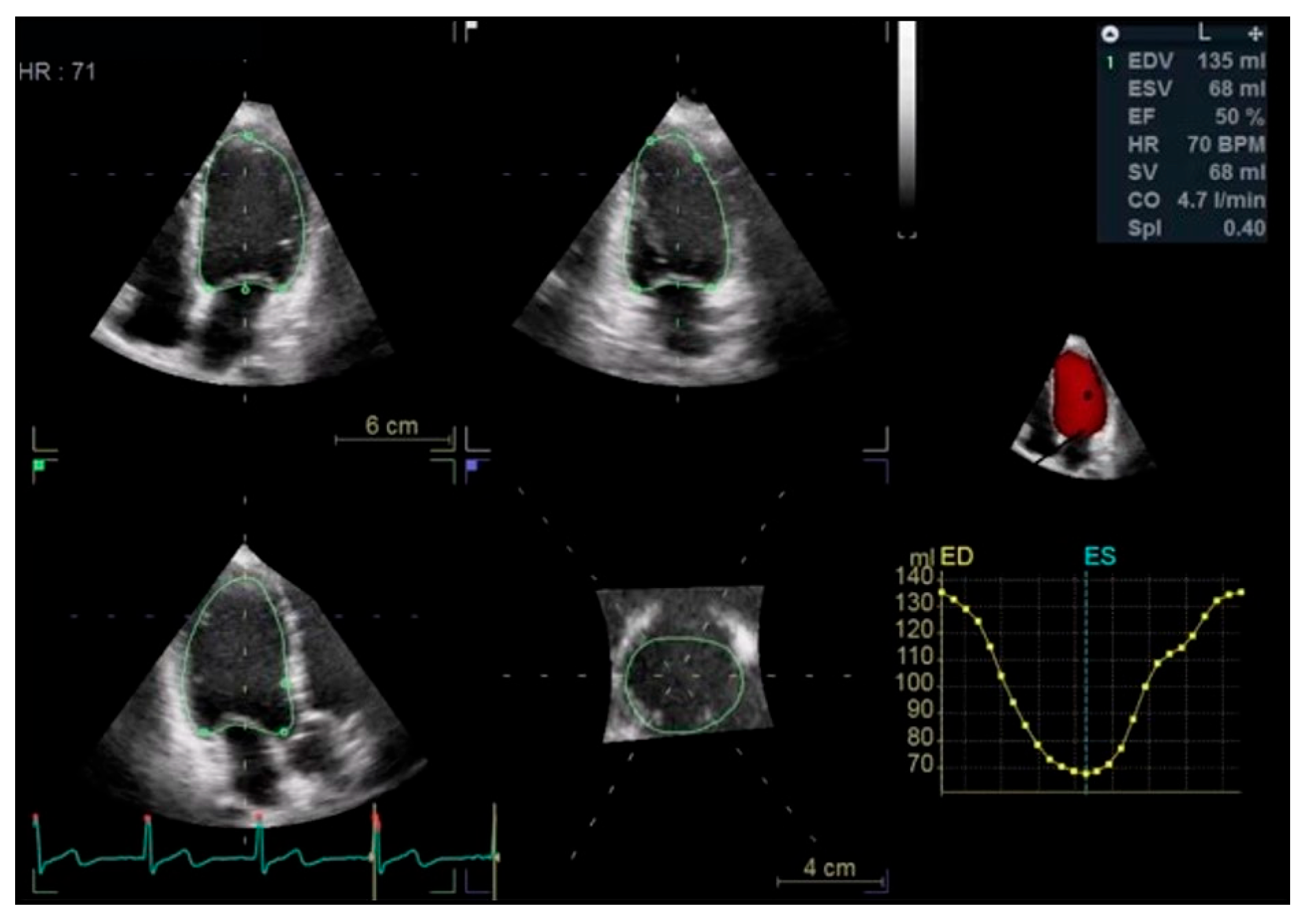

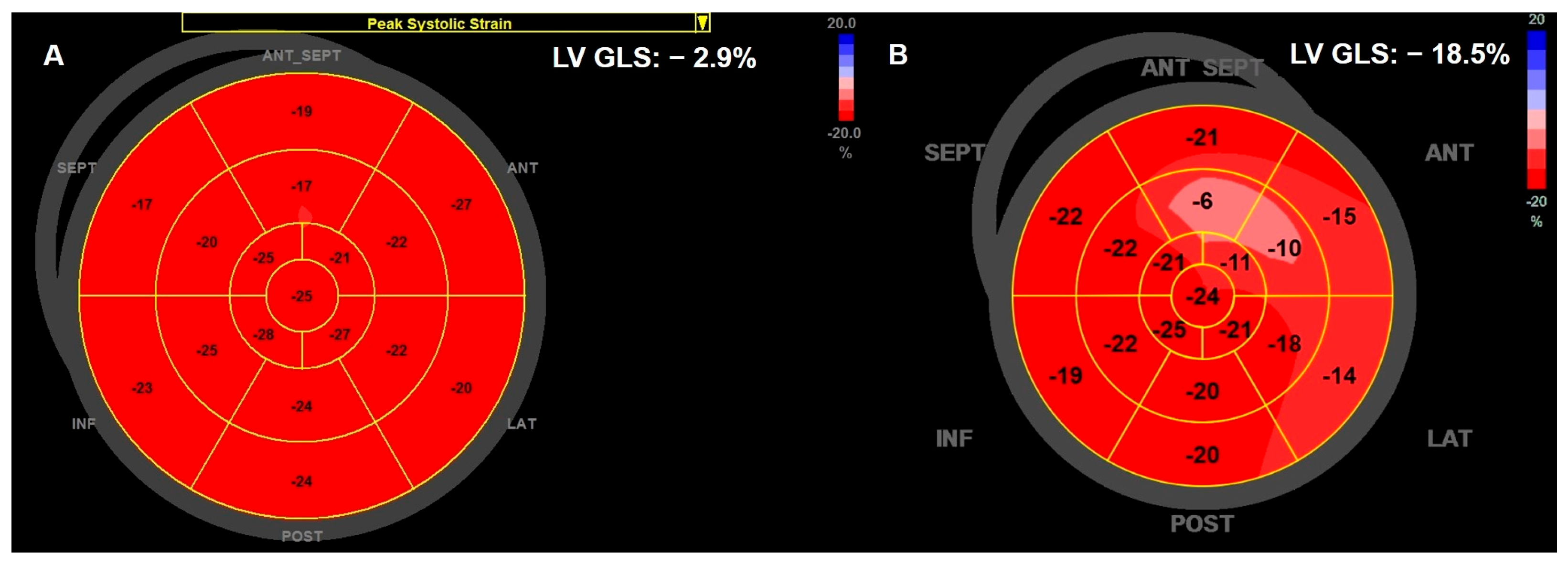

Left Ventricular Systolic Function

Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

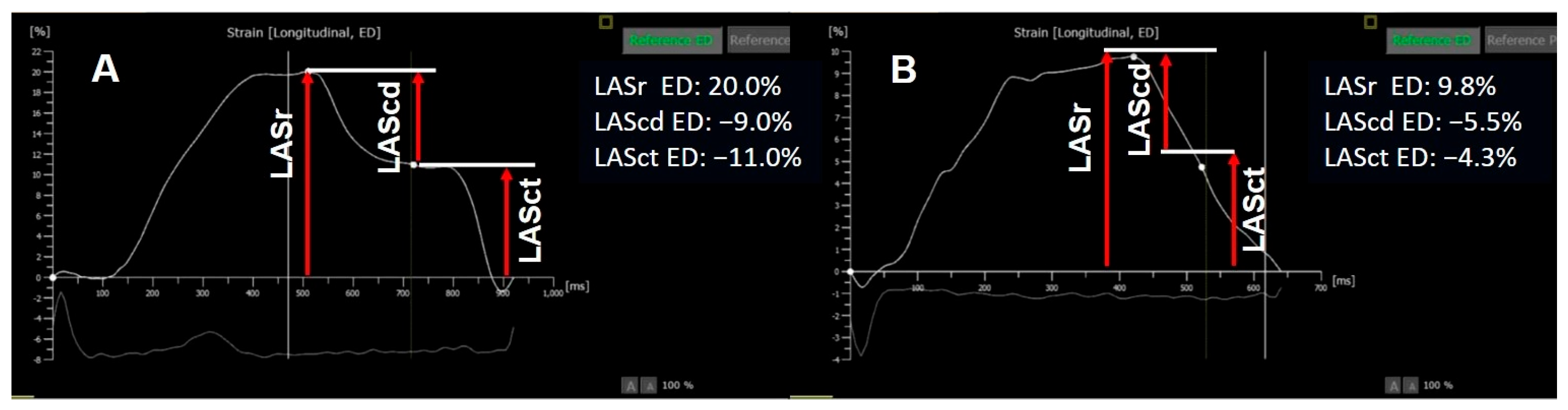

Left Atrium

Right Ventricular Size and Function

Stress Echocardiography—Functional Myocardial Ischemia Assessment

3.1.2. Surveillance and Identification of CTRCD

Left Ventricular Systolic Function

Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

Left Atrium

Right Ventricle

Pulmonary Hypertension

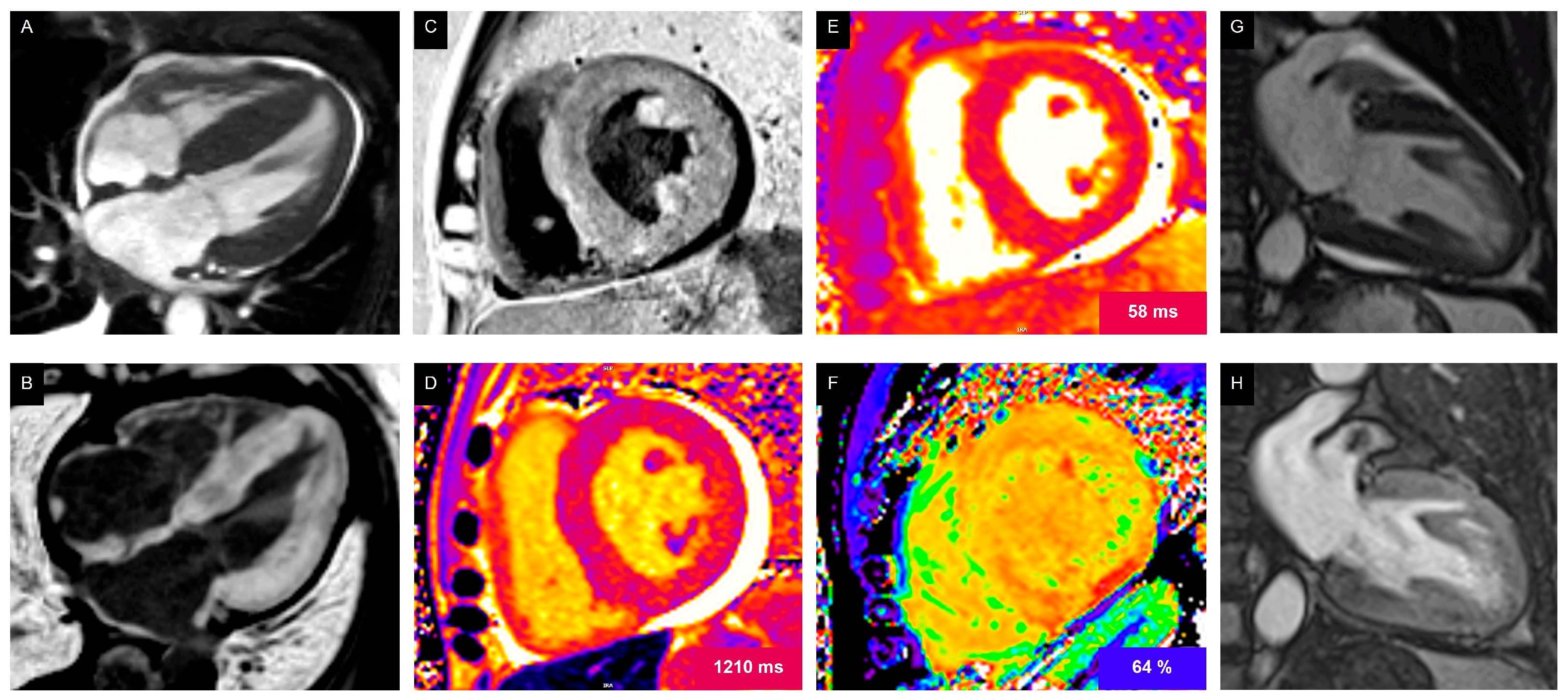

3.2. Cardiac Magnetic Imaging

3.2.1. Baseline Assessment

3.2.2. Surveillance and Identification of CTR-CVT

Myocardial Dysfunction

Detection of Early and Late Cardiotoxicity

Myocarditis

Pericardial Disease

3.3. Nuclear Medicine Imaging

3.3.1. Baseline Assessment

3.3.2. Identification of CTRCD

3.3.3. Amyloid Cardiomyopathy

3.3.4. Inflammation

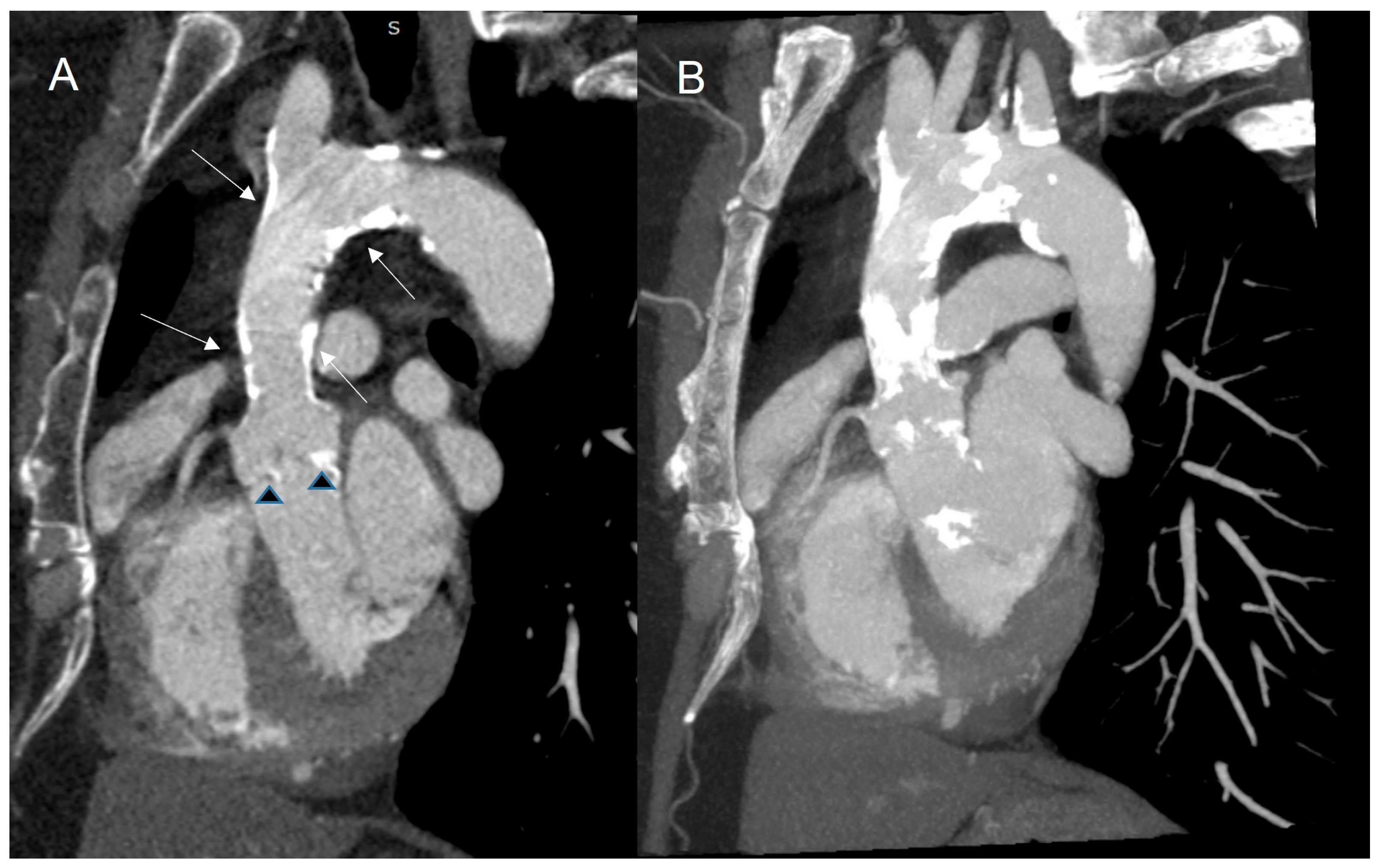

3.4. Cardiac Computed Tomography

3.4.1. Baseline Assessment

3.4.2. Identification of CTRCD

3.5. Role of CVMI in Assessing Late Cardiovascular Complications After Radiotherapy

3.5.1. Coronary Artery Disease

3.5.2. Valvular Heart Disease

3.5.3. Pericardial Disease

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Cordoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on Cardio-Oncology Developed in Collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4229–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, L.A.; Ganatra, S.; Lopez-Mattei, J.; Yang, E.H.; Zaha, V.G.; Wong, T.C.; Ayoub, C.; DeCara, J.M.; Dent, S.; Deswal, A.; et al. Advances in Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 1560–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.T.H.; Bickford, C.L. Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 2231–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Forni, M.; Malet-Martino, M.C.; Jaillais, P.; Shubinski, R.E.; Bachaud, J.M.; Lemaire, L.; Canal, P.; Chevreau, C.; Carrié, D.; Soulié, P. Cardiotoxicity of High-Dose Continuous Infusion Fluorouracil: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1992, 10, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorosz, J.L.; Lezotte, D.C.; Weitzenkamp, D.A.; Allen, L.A.; Salcedo, E.E. Performance of 3-Dimensional Echocardiography in Measuring Left Ventricular Volumes and Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Badano, L.P.; Peluso, D.; Dal Bianco, L.; Casablanca, S.; Kocabay, G.; Zoppellaro, G.; Iliceto, S. Comprehensive Analysis of Left Ventricular Geometry and Function by Three-Dimensional Echocardiography in Healthy Adults. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senior, R.; Becher, H.; Monaghan, M.; Agati, L.; Zamorano, J.; Vanoverschelde, J.L.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; Edvardsen, T.; Lancellotti, P.; Delgado, V.; et al. Clinical Practice of Contrast Echocardiography: Recommendation by the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) 2017. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 18, 1205–1205af. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, R.; Timperley, J.; Cezary, S.; Monaghan, M.; Nihoyannopoulis, P.; Senior, R.; Becher, H. The Clinical Applications of Contrast Echocardiography. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2007, 8, S13–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oikonomou, E.K.; Kokkinidis, D.G.; Kampaktsis, P.N.; Amir, E.A.; Marwick, T.H.; Gupta, D.; Thavendiranathan, P. Assessment of Prognostic Value of Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain for Early Prediction of Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, N.; Tan, T.C.; Ali, M.; Halpern, E.F.; Wang, L.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Echocardiographic Parameters of Left Ventricular Size and Function as Predictors of Symptomatic Heart Failure in Patients with a Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction of 50-59% Treated with Anthracyclines. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.T.; Yucel, E.; Bouras, S.; Wang, L.; Fei, H.; Halpern, E.F.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Myocardial Strain Is Associated with Adverse Clinical Cardiac Events in Patients Treated with Anthracyclines. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 522–527.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fung, J.W.H.; Ho, P.Y.; Sanderson, J.E. Left Ventricular Long Axis Function in Diastolic Heart Failure Is Reduced in Both Diastole and Systole: Time for a Redefinition? Heart 2002, 87, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor-Avi, V.; Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Belohlavek, M.; Cardim, N.M.; Derumeaux, G.; Galderisi, M.; Marwick, T.; Nagueh, S.F.; Sengupta, P.P.; et al. Current and Evolving Echocardiographic Techniques for the Quantitative Evaluation of Cardiac Mechanics: ASE/EAE Consensus Statement on Methodology and Indications. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 277–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.; Eriksen, M.; Aaberge, L.; Wilhelmsen, N.; Skulstad, H.; Remme, E.W.; Haugaa, K.H.; Opdahl, A.; Fjeld, J.G.; Gjesdal, O.; et al. A Novel Clinical Method for Quantification of Regional Left Ventricular Pressure–Strain Loop Area: A Non-Invasive Index of Myocardial Work. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmensen, T.S.; Eiskjær, H.; Ladefoged, B.; Mikkelsen, F.; Sørensen, J.; Granstam, S.-O.; Rosengren, S.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Poulsen, S.H. Prognostic Implications of Left Ventricular Myocardial Work Indices in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, F.; Postolache, A.; Dulgheru, R.; Marchetta, S.; Cicenia, M.; Lancellotti, P. Prognostic Role of Global Work Index in Asymptomatic Patients with Aortic Stenosis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, ehaa946.0091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.; Buytaert, D.; Beles, M.; Paolisso, P.; Duchenne, J.; Huygh, G.; Langmans, C.; Roelstraete, A.; Verstreken, S.; Goethals, M.; et al. Serial Non-Invasive Myocardial Work Measurements for Patient Risk Stratification and Early Detection of Cancer Therapeutics-Related Cardiac Dysfunction in Breast Cancer Patients: A Single-Centre Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo-Argüelles, O.; Thampinathan, B.; Somerset, E.; Shalmon, T.; Amir, E.; Steve Fan, C.-P.; Moon, S.; Abdel-Qadir, H.; Thevakumaran, Y.; Day, J.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Myocardial Work Indices for Identification of Cancer Therapy–Related Cardiotoxicity. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1361–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F.; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upshaw, J.N.; Finkelman, B.; Hubbard, R.A.; Smith, A.M.; Narayan, H.K.; Arndt, L.; Domchek, S.; DeMichele, A.; Fox, K.; Shah, P.; et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Changes in Left Ventricular Diastolic Function with Contemporary Breast Cancer Therapy. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincu, R.I.; Lampe, L.F.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Kimmig, R.; Rassaf, T.; Totzeck, M. Left Ventricular Diastolic Function Following Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy in Patients with Breast Cancer without Previous Cardiac Disease—A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, F.; Cautela, J.; Ancedy, Y.; Resseguier, N.; Aurran, T.; Farnault, L.; Escudier, M.; Ammar, C.; Gaubert, M.; Dolladille, C.; et al. High Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients Treated with Ibrutinib. Open Heart 2019, 6, e001049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, R.; Feinglass, J.; Ma, S.; Akhter, N. Risk Factors for the Development of Atrial Fibrillation on Ibrutinib Treatment. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reda, G.; Fattizzo, B.; Cassin, R.; Mattiello, V.; Tonella, T.; Giannarelli, D.; Massari, F.; Cortelezzi, A. Predictors of Atrial Fibrillation in Ibrutinib-Treated CLL Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiello, V.; Barone, A.; Giannarelli, D.; Noto, A.; Cecchi, N.; Rampi, N.; Cassin, R.; Reda, G. Predictors of Ibrutinib-associated Atrial Fibrillation: 5-year Follow-up of a Prospective Study. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 41, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; El Hangouche, N.; McGee, K.; Gong, F.; Lentz, R.; Feinglass, J.; Akhter, N. Utilizing Left Atrial Strain to Identify Patients at Risk for Atrial Fibrillation on Ibrutinib. Echocardiography 2021, 38, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anavekar, N.S.; Skali, H.; Bourgoun, M.; Ghali, J.K.; Kober, L.; Maggioni, A.P.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Velazquez, E.; Califf, R.; Pfeffer, M.A.; et al. Usefulness of Right Ventricular Fractional Area Change to Predict Death, Heart Failure, and Stroke Following Myocardial Infarction (from the VALIANT ECHO Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramida, K.; Farmakis, D.; Bingcang, J.; Sulemane, S.; Sutherland, S.; Bingcang, R.A.; Ramachandran, K.; Tzavara, C.; Charalampopoulos, G.; Filippiadis, D.; et al. Longitudinal Changes of Right Ventricular Deformation Mechanics during Trastuzumab Therapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2019, 21, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthur, A.; Brezden-Masley, C.; Connelly, K.A.; Dhir, V.; Chan, K.K.W.; Haq, R.; Kirpalani, A.; Barfett, J.J.; Jimenez-Juan, L.; Karur, G.R.; et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Right Ventricular Structure and Function by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Trastuzumab: A Prospective Observational Study. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2016, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-T.; Shih, J.-Y.; Feng, Y.-H.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chen, W.-Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Cheng, J.-T.; Wang, J.-J.; Chen, Z.-C. The Early Predictive Value of Right Ventricular Strain in Epirubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Patients with Breast Cancer. Acta. Cardiol. Sin. 2016, 32, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plana, J.C.; Galderisi, M.; Barac, A.; Ewer, M.S.; Ky, B.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Ganame, J.; Sebag, I.A.; Agler, D.A.; Badano, L.P.; et al. Expert Consensus for Multimodality Imaging Evaluation of Adult Patients during and after Cancer Therapy: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 911–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.T.H.; Tong, A.T.; Lenihan, D.J.; Yusuf, S.W.; Swafford, J.; Champion, C.; Durand, J.-B.; Gibbs, H.; Zafarmand, A.A.; Ewer, M.S. Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy. Circulation 2004, 109, 3122–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.; Helfrich, I.; Hendgen-Cotta, U.B.; Mincu, R.-I.; Korste, S.; Mrotzek, S.M.; Spomer, A.; Odersky, A.; Rischpler, C.; Herrmann, K.; et al. Targeting Early Stages of Cardiotoxicity from Anti-PD1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.E.; Barac, A.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Strain Imaging in Cardio-Oncology. JACC Cardio Oncol. 2020, 2, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CAIANI, E. Improved Semiautomated Quantification of Left Ventricular Volumes and Ejection Fraction Using 3-Dimensional Echocardiography with a Full Matrix-Array Transducer: Comparison with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor-Avi, V.; Jenkins, C.; Kühl, H.P.; Nesser, H.-J.; Marwick, T.; Franke, A.; Ebner, C.; Freed, B.H.; Steringer-Mascherbauer, R.; Pollard, H.; et al. Real-Time 3-Dimensional Echocardiographic Quantification of Left Ventricular Volumes. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2008, 1, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galema, T.W.; van de Ven, A.R.T.; Soliman, O.I.I.; van Domburg, R.T.; Vletter, W.B.; van Dalen, B.M.; Nemes, A.; ten Cate, F.J.; Geleijnse, M.L. Contrast Echocardiography Improves Interobserver Agreement for Wall Motion Score Index and Correlation with Ejection Fraction. Echocardiography 2011, 28, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Barletta, G.; von Bardeleben, S.; Vanoverschelde, J.L.; Kasprzak, J.; Greis, C.; Becher, H. Analysis of Left Ventricular Volumes and Function: A Multicenter Comparison of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Cine Ventriculography, and Unenhanced and Contrast-Enhanced Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavendiranathan, P.; Grant, A.D.; Negishi, T.; Plana, J.C.; Popović, Z.B.; Marwick, T.H. Reproducibility of Echocardiographic Techniques for Sequential Assessment of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction and Volumes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Rad, N.; Walker, J.R.; Wassef, A.; Lytwyn, M.; Bohonis, S.; Fang, T.; Tian, G.; Kirkpatrick, I.D.C.; Singal, P.K.; Krahn, M.; et al. The Utility of Cardiac Biomarkers, Tissue Velocity and Strain Imaging, and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Predicting Early Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients with Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor II–Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Adjuvant Trastuzumab Therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcut, R.; Wildiers, H.; Ganame, J.; D’hooge, J.; De Backer, J.; Denys, H.; Paridaens, R.; Rademakers, F.; Voigt, J.-U. Strain Rate Imaging Detects Early Cardiac Effects of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin as Adjuvant Therapy in Elderly Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotrionte, M.; Cavarretta, E.; Abbate, A.; Mezzaroma, E.; De Marco, E.; Di Persio, S.; Loperfido, F.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Frati, G.; Palazzoni, G. Temporal Changes in Standard and Tissue Doppler Imaging Echocardiographic Parameters After Anthracycline Chemotherapy in Women with Breast Cancer. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, J.M.; Sogaard, P.; Mortensen, C.E.; Skagen, K.; Nielsen, D.L. Tissue-Doppler Assessment of Cardiac Left Ventricular Function during Short-Term Adjuvant Epirubicin Therapy for Breast Cancer. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavendiranathan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zafar, A.; Drobni, Z.D.; Mahmood, S.S.; Cabral, M.; Awadalla, M.; Nohria, A.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Thuny, F.; et al. Myocardial T1 and T2 Mapping by Magnetic Resonance in Patients With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Myocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, T.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Penicka, M.; Lemieux, J.; Murbraech, K.; Miyazaki, S.; Shirazi, M.; Santoro, C.; Cho, G.-Y.; Popescu, B.A.; et al. Cardioprotection Using Strain-Guided Management of Potentially Cardiotoxic Cancer Therapy. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celebi Coskun, E.; Coskun, A.; Sahin, A.B.; Levent, F.; Coban, E.; Koca, F.; Sali, S.; Demir, O.F.; Deligonul, A.; Tenekecioglu, E.; et al. Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front. Oncol 2024, 14, 1453721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, K.; Negishi, T.; Hare, J.L.; Haluska, B.A.; Plana, J.C.; Marwick, T.H. Independent and Incremental Value of Deformation Indices for Prediction of Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiotoxicity. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, H.K.; French, B.; Khan, A.M.; Plappert, T.; Hyman, D.; Bajulaiye, A.; Domchek, S.; DeMichele, A.; Clark, A.; Matro, J.; et al. Noninvasive Measures of Ventricular-Arterial Coupling and Circumferential Strain Predict Cancer Therapeutics–Related Cardiac Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinaglia, T.; Gongora, C.; Awadalla, M.; Hassan, M.Z.O.; Zafar, A.; Drobni, Z.D.; Mahmood, S.S.; Zhang, L.; Coelho-Filho, O.R.; Suero-Abreu, G.A.; et al. Global Circumferential and Radial Strain Among Patients With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Myocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.-Y.; Sun, J.P.; Lee, A.P.; Yang, X.S.; Qiao, Z.; Luo, X.; Fang, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, J.-G. Three-Dimensional Speckle Strain Echocardiography Is More Accurate and Efficient than 2D Strain in the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Function. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 176, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Yu, W.; Cheuk, D.K.L.; Wong, S.J.; Chan, G.C.F.; Cheung, Y. New Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography Identifies Global Impairment of Left Ventricular Mechanics with a High Sensitivity in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mornoş, C.; Manolis, A.J.; Cozma, D.; Kouremenos, N.; Zacharopoulou, I.; Ionac, A. The Value of Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain Assessed by Three-Dimensional Strain Imaging in the Early Detection of Anthracyclinemediated Cardiotoxicity. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2014, 55, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, E.; Brown, A.; Barrett, P.; Morgan, R.B.; King, G.; Kennedy, M.J.; Murphy, R.T. Subclinical Anthracycline- and Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiotoxicity in the Long-Term Follow-up of Asymptomatic Breast Cancer Survivors: A Speckle Tracking Echocardiographic Study. Heart 2010, 96, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.M.; González, I.; Del Castillo, S.; Muñiz, J.; Morales, L.J.; Moreno, F.; Jiménez, R.; Cristóbal, C.; Graupner, C.; Talavera, P.; et al. Diastolic Dysfunction Following Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients: Incidence and Predictors. Oncologist 2015, 20, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, M.; Magda, L.S.; Enescu, O.A.; Jinga, D.; Vinereanu, D. Early Detection of Epirubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, P.W.; Richards, D.A.B.; Boyd, A.; Hui, R.; Harnett, P.R.; Meikle, S.R.; Clarke, J.L.; Thomas, L. Altered Left Ventricular Longitudinal Diastolic Function Correlates with Reduced Systolic Function Immediately after Anthracycline Chemotherapy. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 14, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, G.C.; Karon, B.L.; Mahoney, D.W.; Redfield, M.M.; Roger, V.L.; Burnett, J.C.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Rodeheffer, R.J. Progression of Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction and Risk of Heart Failure. JAMA 2011, 306, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamini, C.; Dolci, G.; Rossi, A.; Torelli, F.; Ghiselli, L.; Trevisani, L.; Vinco, G.; Truong, S.; La Russa, F.; Golia, G.; et al. Left Atrial Volume in Patients with HER2-positive Breast Cancer: One Step Further to Predict Trastuzumab-related Cardiotoxicity. Clin. Cardiol. 2018, 41, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Cho, J.Y.; Yoon, H.J.; Hong, Y.J.; Park, H.W.; Kim, J.H.; Ahn, Y.; Jeong, M.H.; et al. Left Atrial Longitudinal Strain as a Predictor of Cancer Therapeutics-Related Cardiac Dysfunction in Patients with Breast Cancer. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2020, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Machino-Ohtsuka, T.; Nakazawa, Y.; Iida, N.; Sasamura, R.; Bando, H.; Chiba, S.; Tasaka, N.; Ishizu, T.; Murakoshi, N.; et al. Early Detection and Prediction of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity―A Prospective Cohort Study. Circ. J. 2024, 88, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, A.; Poulin, F.; Khorolsky, C.; Shariat, M.; Bedard, P.L.; Amir, E.; Rakowski, H.; McDonald, M.; Delgado, D.; Thavendiranathan, P. Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients Experiencing Cardiotoxicity during Breast Cancer Therapy. J. Oncol. 2015, 2015, 609194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, J.; Totzeck, M.; Mincu, R.; Margraf, S.M.; Scheipers, L.; Michel, L.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Zimmer, L.; Rassaf, T.; Hendgen-Cotta, U.B. Right Ventricular and Atrial Strain in Patients with Advanced Melanoma Undergoing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 3533–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, D.; Bergot, E.; Günther, S.; Savale, L.; Bergeron, A.; Bourdin, A.; Bouvaist, H.; Canuet, M.; Pison, C.; Macro, M.; et al. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Patients Treated by Dasatinib. Circulation 2012, 125, 2128–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Lladó, G. Assessment of Cardiac Function by CMR. Eur. Radiol. Suppl. 2005, 15, B23–B32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothues, F.; Moon, J.C.; Bellenger, N.G.; Smith, G.S.; Klein, H.U.; Pennell, D.J. Interstudy Reproducibility of Right Ventricular Volumes, Function, and Mass with Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Am. Heart J. 2004, 147, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothues, F.; Smith, G.C.; Moon, J.C.C.; Bellenger, N.G.; Collins, P.; Klein, H.U.; Pennell, D.J. Comparison of Interstudy Reproducibility of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance with Two-Dimensional Echocardiography in Normal Subjects and in Patients with Heart Failure or Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, R.Y.; Ge, Y.; Steel, K.; Bingham, S.; Abdullah, S.; Fujikura, K.; Wang, W.; Pandya, A.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Mikolich, J.R.; et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Stress Perfusion Imaging for Evaluation of Patients With Chest Pain. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.C.; Gidding, S.; Gjesdal, O.; Wu, C.; Bluemke, D.A.; Lima, J.A.C. LV Mass Assessed by Echocardiography and CMR, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Medical Practice. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylänen, K.; Poutanen, T.; Savikurki-Heikkilä, P.; Rinta-Kiikka, I.; Eerola, A.; Vettenranta, K. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of the Late Effects of Anthracyclines Among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, F.; Vizzari, G.; Qamar, R.; Bomzer, C.; Carerj, S.; Zito, C.; Khandheria, B.K. Multimodality Imaging in Cardiooncology. J. Oncol. 2015, 2015, 263950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, G.; Brezden-Masley, C.; Dhir, V.; Deva, D.P.; Chan, K.K.W.; Chow, C.-M.; Thavendiranathan, D.; Haq, R.; Barfett, J.J.; Petrella, T.M.; et al. Myocardial Strain Imaging by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance for Detection of Subclinical Myocardial Dysfunction in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Trastuzumab and Chemotherapy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 261, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drafts, B.C.; Twomley, K.M.; D’Agostino, R.; Lawrence, J.; Avis, N.; Ellis, L.R.; Thohan, V.; Jordan, J.; Melin, S.A.; Torti, F.M.; et al. Low to Moderate Dose Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy Is Associated With Early Noninvasive Imaging Evidence of Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.H.; Sukpraphrute, B.; Meléndez, G.C.; Jolly, M.-P.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Hundley, W.G. Early Myocardial Strain Changes During Potentially Cardiotoxic Chemotherapy May Occur as a Result of Reductions in Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume. Circulation 2017, 135, 2575–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschenhagen, T.; Force, T.; Ewer, M.S.; de Keulenaer, G.W.; Suter, T.M.; Anker, S.D.; Avkiran, M.; de Azambuja, E.; Balligand, J.; Brutsaert, D.L.; et al. Cardiovascular Side Effects of Cancer Therapies: A Position Statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messroghli, D.R.; Moon, J.C.; Ferreira, V.M.; Grosse-Wortmann, L.; He, T.; Kellman, P.; Mascherbauer, J.; Nezafat, R.; Salerno, M.; Schelbert, E.B.; et al. Clinical Recommendations for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Mapping of T1, T2, T2* and Extracellular Volume: A Consensus Statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI). J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2016, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.M.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Holmvang, G.; Kramer, C.M.; Carbone, I.; Sechtem, U.; Kindermann, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Cooper, L.T.; Liu, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3158–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Canby, R.C.; Lojeski, E.W.; Ratner, A.V.; Fallon, J.T.; Pohost, G.M. Adriamycin Cardiotoxicity and Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxation Properties. Am. Heart J. 1987, 113, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrage, M.K.; Ferreira, V.M. The Use of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance as an Early Non-Invasive Biomarker for Cardiotoxicity in Cardio-Oncology. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavendiranathan, P.; Wintersperger, B.J.; Flamm, S.D.; Marwick, T.H. Cardiac MRI in the Assessment of Cardiac Injury and Toxicity From Cancer Chemotherapy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavendiranathan, P.; Amir, E.; Bedard, P.; Crean, A.; Paul, N.; Nguyen, E.T.; Wintersperger, B.J. Regional Myocardial Edema Detected by T2 Mapping Is a Feature of Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Sequential Therapy with Anthracyclines and Trastuzumab. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2014, 16, P273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Takahashi, M.; Kimura, F.; Senoo, T.; Saeki, T.; Ueda, S.; Tanno, J.; Senbonmatsu, T.; Kasai, T.; Nishimura, S. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Myocardial Strain Study for Evaluation of Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Trastuzumab: A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility of the Method. Cardiol. J. 2016, 23, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlberg, F.; Funk, S.; Zange, L.; von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff, F.; Blaszczyk, E.; Schulz, A.; Ghani, S.; Reichardt, A.; Reichardt, P.; Schulz-Menger, J. Native Myocardial T1 Time Can Predict Development of Subsequent Anthracycline-induced Cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail 2018, 5, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, I.; Biglino, G.; Baritussio, A.; De Garate, E.; Dastidar, A.; Plana, J.C.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C. Long Term Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Phenotyping of Anthracycline Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 292, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilan, T.G.; Coelho-Filho, O.R.; Pena-Herrera, D.; Shah, R.V.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Francis, S.A.; Moslehi, J.; Kwong, R.Y. Left Ventricular Mass in Patients With a Cardiomyopathy After Treatment With Anthracyclines. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.; Joppa, S.; Chen, K.-H.A.; Athwal, P.S.S.; Okasha, O.; Velangi, P.S.; Hooks, M.; Nijjar, P.S.; Blaes, A.H.; Shenoy, C. Myocardial Damage Assessed by Late Gadolinium Enhancement on Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cancer Patients Treated with Anthracyclines and/or Trastuzumab. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.R.; Dolladille, C.; Procureur, A.; Ederhy, S.R.; Palaskas, N.L.; Lehmann, L.H.; Cautela, J.; Courand, P.-Y.; Hayek, S.S.; Zhu, H.; et al. Predictors and Risk Score for Immune Checkpoint-Inhibitor-Associated Myocarditis Severity. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C.M.; Hanson, C.A. CMR Parametric Mapping in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Myocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitel, I.; von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff, F.; Bernhardt, P.; Carbone, I.; Muellerleile, K.; Aldrovandi, A.; Francone, M.; Desch, S.; Gutberlet, M.; Strohm, O.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Stress (Takotsubo) Cardiomyopathy. JAMA 2011, 306, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamori, S.; Matsuoka, K.; Onishi, K.; Kurita, T.; Ichikawa, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Ishida, M.; Kitagawa, K.; Tanigawa, T.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Prevalence and Signal Characteristics of Late Gadolinium Enhancement on Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy. Circ. J. 2012, 76, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchner, T.; Mincu, R.I.; Bühning, F.; Vogel, J.; Klingel, K.; Meetschen, M.; Schlosser, T.; Haubold, J.; Umutlu, L.; Dobrev, D.; et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Suspected Myocarditis from Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy—A Real-World Observational Study. IJC Heart Vasc. 2025, 56, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Bhullar, N.; Fallah-Rad, N.; Lytwyn, M.; Golian, M.; Fang, T.; Summers, A.R.; Singal, P.K.; Barac, I.; Kirkpatrick, I.D.; et al. Role of Three-Dimensional Echocardiography in Breast Cancer: Comparison With Two-Dimensional Echocardiography, Multiple-Gated Acquisition Scans, and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3429–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischpler, C.; Nekolla, S.G.; Dregely, I.; Schwaiger, M. Hybrid PET/MR Imaging of the Heart: Potential, Initial Experiences, and Future Prospects. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, T.; Nakajima, K.; Yamashina, S.; Yamada, T.; Momose, M.; Kasama, S.; Matsui, T.; Matsuo, S.; Travin, M.I.; Jacobson, A.F. A Pooled Analysis of Multicenter Cohort Studies of 123I-MIBG Imaging of Sympathetic Innervation for Assessment of Long-Term Prognosis in Heart Failure. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekakis, J.; Prassopoulos, V.; Athanassiadis, P.; Kostamis, P.; Moulopoulos, S. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Neurotoxicity: Study with Iodine 123-Labeled Metaiodobenzylguanidine Scintigraphy. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 1996, 3, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjrath, G.S.; Jain, D. Monitoring Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Role of Cardiac Nuclear Imaging. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2006, 13, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrió, I.; Estorch, M.; Berná, L.; López-Pousa, J.; Tabernero, J.; Torres, G. Indium-111-Antimyosin and Iodine-123-MIBG Studies in Early Assessment of Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, 36, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap, L.G.; Dominici, F.; Wang, Y.; El-Sady, M.S.; Singh, A.; Di Carli, M.F.; Falk, R.H.; Dorbala, S. Epidemiology of Cardiac Amyloidosis–Associated Heart Failure Hospitalizations Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. Circ. Heart Fail 2019, 12, e005407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, A.; Bukhari, S.; Ahmad, S.; Nieves, R.; Eisele, Y.S.; Follansbee, W.; Brownell, A.; Wong, T.C.; Schelbert, E.; Soman, P. Efficient 1-Hour Technetium-99 m Pyrophosphate Imaging Protocol for the Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e010249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, D.; Neilan, T.G.; Barac, A.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Okwuosa, T.M.; Plana, J.C.; Reding, K.W.; Taqueti, V.R.; Yang, E.H.; Zaha, V.G. Cardiovascular Imaging in Contemporary Cardio-Oncology: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiecki, S.; Sterliński, M.; Marciniak-Emmons, M.; Dziuk, M. Feasibility of 18FDG PET in the Cardiac Inflammation. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 37, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarocchi, M.; Bauckneht, M.; Arboscello, E.; Capitanio, S.; Marini, C.; Morbelli, S.; Miglino, M.; Congiu, A.G.; Ghigliotti, G.; Balbi, M.; et al. An Increase in Myocardial 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake Is Associated with Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Decline in Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients Treated with Anthracycline. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughdad, S.; Latifyan, S.; Fenwick, C.; Bouchaab, H.; Suffiotti, M.; Moslehi, J.J.; Salem, J.-E.; Schaefer, N.; Nicod-Lalonde, M.; Costes, J.; et al. 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT to Detect Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Myocarditis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury, R.C.; Abbara, S.; Achenbach, S.; Agatston, A.; Berman, D.S.; Budoff, M.J.; Dill, K.E.; Jacobs, J.E.; Maroules, C.D.; Rubin, G.D.; et al. CAD-RADSTM Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System. An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2016, 10, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available online: https://Www.Nice.Org.Uk/Guidance/Mtg32 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Bergom, C.; Bradley, J.A.; Ng, A.K.; Samson, P.; Robinson, C.; Lopez-Mattei, J.; Mitchell, J.D. Past, Present, and Future of Radiation-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Refinements in Targeting, Surveillance, and Risk Stratification. JACC CardioOncol. 2021, 3, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, J.D.; Kaur, J.; Khodadadi, R.; Rehman, M.; Lobo, R.; Chakrabarti, S.; Herrmann, J.; Lerman, A.; Grothey, A. 5-Fluorouracil and Cardiotoxicity: A Review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018, 10, 1758835918780140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nimwegen, F.A.; Schaapveld, M.; Janus, C.P.M.; Krol, A.D.G.; Petersen, E.J.; Raemaekers, J.M.M.; Kok, W.E.M.; Aleman, B.M.P.; van Leeuwen, F.E. Cardiovascular Disease After Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nimwegen, F.A.; Schaapveld, M.; Cutter, D.J.; Janus, C.P.M.; Krol, A.D.G.; Hauptmann, M.; Kooijman, K.; Roesink, J.; van der Maazen, R.; Darby, S.C.; et al. Radiation Dose-Response Relationship for Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfill, K.; Giuliani, M.; Aznar, M.; Franks, K.; McWilliam, A.; Schmitt, M.; Sun, F.; Vozenin, M.C.; Faivre Finn, C. Cardiac Toxicity of Thoracic Radiotherapy: Existing Evidence and Future Directions. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Hancock, S.L.; Lee, B.K.; Mariscal, C.S.; Schnittger, I. Asymptomatic Cardiac Disease Following Mediastinal Irradiation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawade, T.; Clavel, M.-A.; Tribouilloy, C.; Dreyfus, J.; Mathieu, T.; Tastet, L.; Renard, C.; Gun, M.; Jenkins, W.S.A.; Macron, L.; et al. Computed Tomography Aortic Valve Calcium Scoring in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, e007146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmel, R.J.; Kaplan, H.S. Mantle Irradiation in Hodgkin’s Disease.An Analysis of Technique, Tumor Eradication, and Complications. Cancer 1976, 37, 2813–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, J.; Francone, M. Pericardial Disease: Value of CT and MR Imaging. Radiology 2013, 267, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modality Imaging | Myocardial Dysfunction | Myocarditis | Coronary Artery Disease | Pericardial Disease | Valvular Heart Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography |

|

|

|

|

|

| Strengths: - Easily accessible, low cost, lack of radiation, available from emergency room to the bedside Limitations: - Operator experience, LV EF interobserver variability - Strain assessments need to be performed on the same vendor machine during follow-up - Acoustic window may be difficult in certain patients (e.g., obesity, lung disease, mastectomy) | |||||

| CMR |

|

|

|

|

|

| Strengths: - higher reproducibility, superior image quality and resolution - cross-sectional imaging - ability to provide tissue-characterization of the LV and pericardium Limitations: - high cost, limited accessibility - severe renal impairment: gadolinium cannot be administered - less accurate results in subjects with arrhythmias or cardiac devices - contraindicated in patients with older cardiac devices | |||||

| Nuclear imaging |

|

| |||

| Strengths: - readily available with good access - MUGA measure of EF is highly reproducible - PET has superior accuracy for ischemia assessment in obese patients Limitations: - radiation - does not provide information about other cardiac structures | |||||

| CT |

|

|

|

| |

| Strengths: - Rapid and readily available - high negative predictive value in CAD evaluation - excellent spatial resolution - may identify and characterize high-risk plaque features Limitations: - radiation - high nefrotoxic risk of contrast agents in elderly, diabetic patients or those with significant renal impairment without dialysis - specific preparation protocols in patients with allergy to iodinated contrast agents - coronary lesions severity assessment may be limited by significant calcifications | |||||

| Symptomatic CTRCD | Very severe | Advanced HF |

| Severe | Recurrent HF hospitalizations | |

| Moderate | Need for outpatient HF therapy intensification | |

| Mild | Mild HF symptoms | |

| Asymptomatic CTRCD | Severe | New LVEF reduction to < 40% |

| Moderate | New LVEF reduction by ≥10 percentage to an LVEF of 40–49% OR New LVEF reduction by <10 percentage to an LVEF of 40–49% AND either new relative decline in GLS by >15% from baseline OR new rise in cardiac biomarkers | |

| Mild | LVEF ≥ 50% AND new relative decline in GLS by >15% from baseline AND/OR new increase in cardiac biomarkers |

| Baseline | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | 3M Post tx | 12M Post tx | |

| Low risk | +++ | + | +++ | ||||||

| Moderate risk | +++ | ++ | +++ | ||||||

| High and very high risk | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Baseline | 3M | 6M | 9M | 12M | 3M Post tx | 12m Post tx | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low and moderate risk | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| High and very high risk | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Baseline | 3M | 4M | 6M | 8M | 9M | 12M Post tx | Every 6–12M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | ++ | |||||||

| Moderate risk | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | |||

| High and very high risk | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Baseline | C2 | C3 | C4 | Every 3C a | Every 6M–12M b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | + | |||||

| High risk | +++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mateescu, A.D.; Mincu, R.I.; Jurcut, R.O. How to Use Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010027

Mateescu AD, Mincu RI, Jurcut RO. How to Use Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleMateescu, Anca Doina, Raluca Ileana Mincu, and Ruxandra Oana Jurcut. 2026. "How to Use Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010027

APA StyleMateescu, A. D., Mincu, R. I., & Jurcut, R. O. (2026). How to Use Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010027