Optimizing Temperature in Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Novel Methods in Heart Transplantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

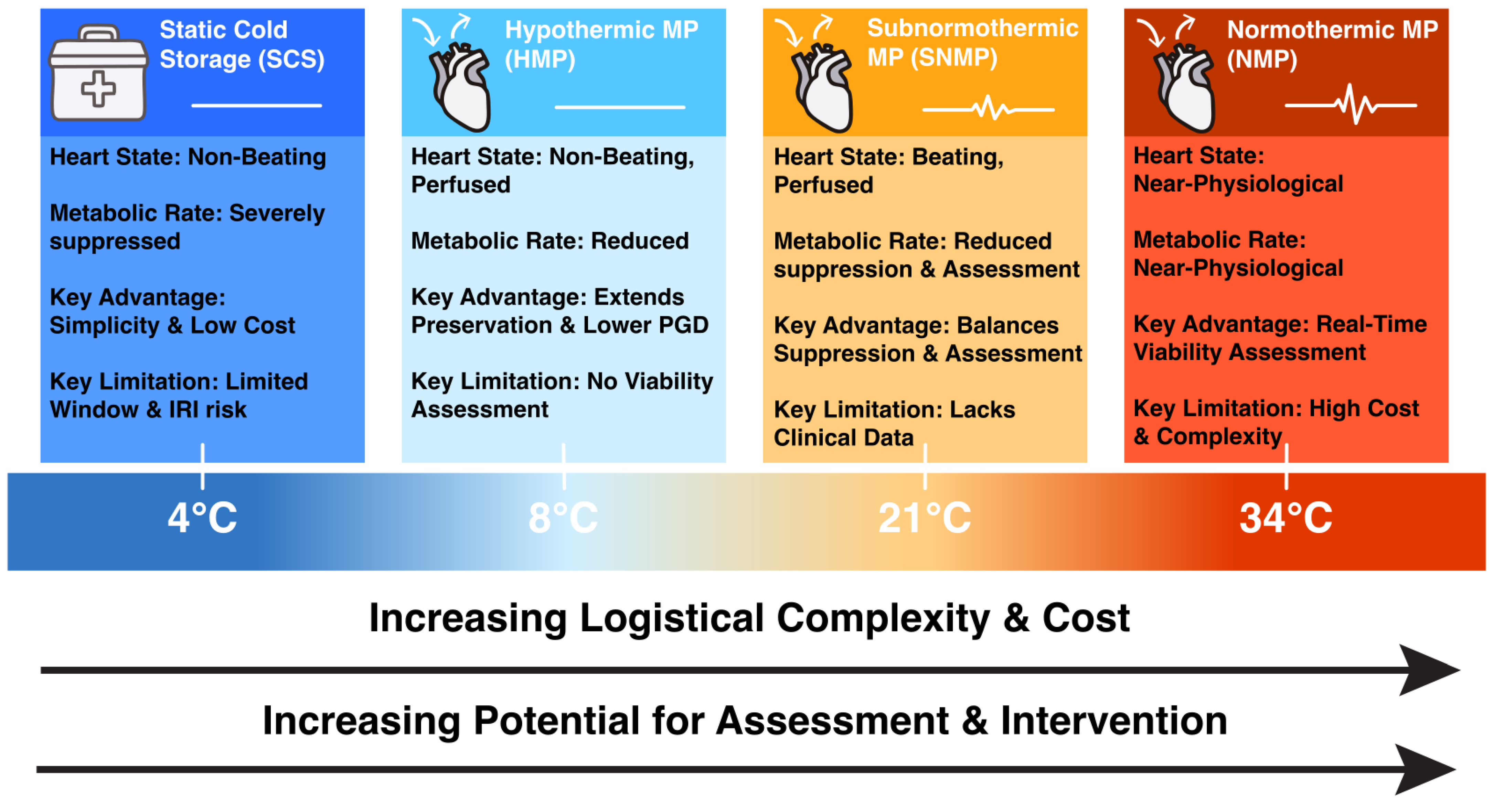

2. Overview of Heart Perfusion and Preservation Techniques

2.1. Static Cold Storage

2.2. Temperature-Controlled Hypothermic Static Storage System

2.3. Normothermic Oxygenated Perfusion

2.4. Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion

2.5. Subnormothermic Oxygenated Perfusion

3. Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Novel Methods

3.1. Preserving the Myocardium

3.2. Impact on Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury and Mitochondria

3.3. Choice of Perfusate

3.4. Patient Outcomes (PGD Rate & Survival)

3.5. Preservation Window and Time Extension

3.6. Functional Assessment During Preservation

3.7. Therapeutic Interventions

3.8. Compatibility with Donor Types

3.9. Health Economics and Logistical Considerations

4. Identifying Gaps and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCS | Static cold storage |

| MP | Machine perfusion |

| NMP | Normothermic machine perfusion |

| HMP | Hypothermic machine perfusion |

| SNMP | Subnormothermic machine perfusion |

| IRI | Ischemia–reperfusion Injury |

| SCTS | SherpaPak® Cardiac Transportation System |

| OCS | Organ Care System™ |

| XHAT | XVIVO Heart Assist Transport™ |

| WIT | Warm ischemia time |

| PGD | Primary graft dysfunction |

| JHLT | Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation |

| MCS | Mechanical circulatory support |

| MACTEs | Major adverse cardiac transplant events |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| DCD | Donation after circulatory death |

| DBD | Donation after brain death |

| TA-NRP | Thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion |

| OER | Oxygen extraction ratio |

| CVR | Coronary vascular resistance |

| MVO2 | Myocardial oxygen consumption |

| ECD | Extended-criteria donor |

| LV | Left ventricular |

References

- Tully, A.; Sharma, S.; Nagalli, S. Heart-Lung Transplantation; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, H.; Hayanga, J.W.A.; Neyrinck, A.; MacDonald, P.; Dellgren, G.; Bertolotti, A.; Khuu, T.; Burrows, F.; Copeland, J.G.; Gooch, D.; et al. Donor Heart and Lung Procurement: A Consensus Statement. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2020, 39, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Baran, D.A. Moving Beyond the Ice Age in Heart Transplant Procurement. Transplantation 2025, 109, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeki, T.; Kwon, M.H.; Gu, J.; Collins, M.J.; Brassil, J.M.; Miller, M.B.; Gullapalli, R.P.; Zhuo, J.; Pierson, R.N.; Griffith, B.P.; et al. Heart Preservation Using Continuous Ex Vivo Perfusion Improves Viability and Functional Recovery. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbade, J.; Krautz, C.; Aupperle, H.; Ullmann, C.; Bittner, H.B.; Dhein, S.; Gummert, J.F.; Mohr, F.-W. 242: Functional, Metabolic, and Morphological Aspects of Continuous, Normothermic Heart Preservation: Effects of Different Preparation and Perfusion Techniques. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2009, 28, S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Caenegem, O.; Beauloye, C.; Bertrand, L.; Horman, S.; Lepropre, S.; Sparavier, G.; Vercruysse, J.; Bethuyne, N.; Poncelet, A.J.; Gianello, P.; et al. Hypothermic Continuous Machine Perfusion Enables Preservation of Energy Charge and Functional Recovery of Heart Grafts in an Ex Vivo Model of Donation Following Circulatory Death. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 49, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, P.S.; Chew, H.C.; Connellan, M.; Dhital, K. Extracorporeal Heart Perfusion before Heart Transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2016, 21, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Schroder, J.; Meyer, D.M.; Vidic, A.; Shudo, Y.; Silvestry, S.; Leacche, M.; Sciortino, C.M.; Rodrigo, M.E.; Pham, S.M.; et al. Impact of Controlled Hypothermic Preservation on Outcomes Following Heart Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, F.O.; Southard, J.H. Principles of Solid-Organ Preservation by Cold Storage. Transplantation 1998, 45, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, L.H.; Khush, K.K.; Cherikh, W.S.; Goldfarb, S.; Kucheryavaya, A.Y.; Levvey, B.J.; Meiser, B.; Rossano, J.W.; Chambers, D.C.; Yusen, R.D.; et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-Fourth Adult Heart Transplantation Report—2017; Focus Theme: Allograft Ischemic Time. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipper, D.A.; Marsh, K.M.; Ferng, A.S.; Duncker, D.J.; Laman, J.D.; Khalpey, Z. The Critical Role of Bioenergetics in Donor Cardiac Allograft Preservation. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2016, 9, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Messer, S.J.; Large, S.R.; Conway, J.; Kim, D.H.; Kutsogiannis, D.J.; Nagendran, J.; Freed, D.H. Transplantation of Hearts Donated after Circulatory Death. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Trahanas, J.M.; Bommareddi, S.; Lima, B.; DeVries, S.A.; Lowman, J.; Ahmad, A.; Quintana, E.; Scholl, S.R.; Tsai, S.; et al. Rapid Recovery of Donor Hearts for Transplantation after Circulatory Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.M.; Michel, S.G.; Ii, G.M.L.; Madariaga, M.L.L. Innovative Cold Storage of Donor Organs Using the Paragonix Sherpa Pak TM Devices. Heart Lung Vessel. 2015, 7, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Shudo, Y.; Leacche, M.; Copeland, H.; Silvestry, S.; Pham, S.M.; Molina, E.; Schroder, J.N.; Sciortino, C.M.; Jacobs, J.P.; Kawabori, M.; et al. A Paradigm Shift in Heart Preservation: Improved Post-Transplant Outcomes in Recipients of Donor Hearts Preserved with the SherpaPak System. ASAIO J. 2023, 69, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, P.S. Cutting the Ice in Donor Heart Preservation. Transplantation 2023, 107, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckermann, A.; Leacche, M.; Philpott, J.; Pham, S.; Shudo, Y.; Bustamante-Munguira, J.; Jacobs, J.; Silvestry, S.; Schroder, J.; Eixeres-Esteve, A.; et al. First Report of Pediatric Outcomes from the GUARDIAN Registry: Multi-Center Analysis of Advanced Organ Preservation for Pediatric Recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, S477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, R.L.; Griffith, B.P. Autoperfusion of the Heart and Lungs for Preservation during Distant Procurement. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1987, 93, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Sáez, D.; Zych, B.; Sabashnikov, A.; Bowles, C.T.; De Robertis, F.; Mohite, P.N.; Popov, A.F.; Maunz, O.; Patil, N.P.; Weymann, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Organ Care System in Heart Transplantation with an Adverse Donor/Recipient Profile. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, A.H.; Elbatanony, A.; Abdelaziem, A.; Solomon, S.D. 241: The Organ Care System (OCS) Enables Ex-Vivo Assessment of Donor Heart Coronary Perfusion Using Contrast Echocardiography. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2009, 28, S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Jernryd, V.; Sjöberg, T.; Steen, S.; Nilsson, J. Machine Perfusion for Human Heart Preservation: A Systematic Review. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicomb, W.N.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Barnard, C.N. Twenty-Four-Hour Preservation of the Pig Heart by a Portable Hypothermic Perfusion System. Transplantation 1982, 34, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicomb, W.N.; Novitzky, D.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Rose, A.G. Forty-Eight Hours Hypothermic Perfusion Storage of Pig and Baboon Hearts. J. Surg. Res. 1986, 40, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicomb, W.N.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Novitzky, D.; Barnard, C.N. Cardiac Transplantation Following Storage of the Donor Heart by a Portable Hypothermic Perfusion System. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1984, 37, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, J.; Jernryd, V.; Qin, G.; Paskevicius, A.; Metzsch, C.; Sjöberg, T.; Steen, S. A Nonrandomized Open-Label Phase 2 Trial of Nonischemic Heart Preservation for Human Heart Transplantation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trahanas, J.M.; Harris, T.; Petrovic, M.; Dreher, A.; Pasrija, C.; DeVries, S.A.; Bommareddi, S.; Lima, B.; Wang, C.C.; Cortelli, M.; et al. Out of the Ice Age: Preservation of Cardiac Allografts with a Reusable 10 °C Cooler. JTCVS Open 2024, 21, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. XVIVO Heart Perfusion System (XHPS) with Supplemented XVIVO Heart Solution (SXHS). Identifier NCT05881278. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05881278?term=preserve%20xvivo&intr=Heart%20Transplantation&rank=1 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Parente, A.; Dondossola, D.; Dutkowski, P.; Schlegel, A. Current Evidence on the Beneficial HOPE-Effect Based on Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Liver Transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, e116–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochmans, I.; Brat, A.; Davies, L.; Hofker, H.S.; van de Leemkolk, F.E.M.; Leuvenink, H.G.D.; Knight, S.R.; Pirenne, J.; Ploeg, R.J.; Abramowicz, D.; et al. Oxygenated versus Standard Cold Perfusion Preservation in Kidney Transplantation (COMPARE): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Paired, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Suylen, V.; Vandendriessche, K.; Neyrinck, A.; Nijhuis, F.; van der Plaats, A.; Verbeken, E.K.; Vermeersch, P.; Meyns, B.; Mariani, M.A.; Rega, F.; et al. Oxygenated Machine Perfusion at Room Temperature as an Alternative for Static Cold Storage in Porcine Donor Hearts. Artif. Organs 2022, 46, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowalekar, S.K.; Cao, H.; Lu, X.G.; Treanor, P.R.; Thatte, H.S. Sub-Normothermic Preservation of Donor Hearts for Transplantation Using a Novel Solution, Somah: A Comparative Pre-Clinical Study. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2014, 33, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morito, N.; Obara, H.; Matsuno, N.; Enosawa, S.; Furukawa, H. Oxygen Consumption during Hypothermic and Subnormothermic Machine Perfusions of Porcine Liver Grafts after Cardiac Death. J. Artif. Organs 2018, 21, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, G.; Hatami, S.; Wagner, M.; Khan, M.; Wang, X.; Pidborochynski, T.; Nagendran, J.; Conway, J.; Freed, D. (866) Subnormothermic Machine Perfusion of Neonatal and Small Pediatric Sized Hearts. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, S376–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckberg, G.D. Myocardial Temperature Management during Aortic Clamping for Cardiac Surgery. Protection, Preoccupation, and Perspective. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1991, 102, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möllhoff, T.; Sukehiro, S.; Flameng, W.; Van Aken, H. Catabolism of High-Energy Phosphates during the Long-Term Preservation of Explanted Donor Hearts in a Dog Model. Anasth. Intensivther. Notfallmed. 1990, 25, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingemansson, R.; Budrikis, A.; Bolys, R.; Sjöberg, T.; Steen, S. Effect of Temperature in Long-Term Preservation of Vascular Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Function. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1996, 61, 1413–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Smith, K.E.; Biro, G.P.; Butler, K.W.; Haas, N.; Scott, J.; Anderson, R.; Deslauriers, R. A Comparison of UW Cold Storage Solution and St. Thomas’ Solution II: A 31P NMR and Functional Study of Isolated Porcine Hearts. J. Heart Lung Transplant. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Heart Transplant. 1991, 10, 975–985. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, P.J.; Walley, V.M.; Koshal, A.; Masters, R.G.; Keon, W.J. Are Temperatures Attained by Donor Hearts during Transport Too Cold? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989, 98, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A.; Rosenfeldt, F.; Hendry, P.J.; Keon, W.J. Temperatures Attained by Donor Hearts Stored in Ice during Transport Are Not Too Cold. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1992, 104, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, M.; Kiernan, Z.; Labate, G.; Chen, Q. Hypothermic Myocardial Preservation: The Freezing Debate. Transplant. Proc. 2025, 57, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, D.H.; Peltz, M.; DiMaio, J.M.; Meyer, D.M.; Wait, M.A.; Merritt, M.E.; Ring, W.S.; Jessen, M.E. Perfusion Preservation versus Static Preservation for Cardiac Transplantation: Effects on Myocardial Function and Metabolism. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2008, 27, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, S.; Freed, D.H. Machine Perfusion of Donor Heart: State of the Art. Curr. Transplant. Rep. 2019, 6, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Caenegem, O.; Beauloye, C.; Vercruysse, J.; Horman, S.; Bertrand, L.; Bethuyne, N.; Poncelet, A.J.; Gianello, P.; Demuylder, P.; Legrand, E.; et al. Hypothermic Continuous Machine Perfusion Improves Metabolic Preservation and Functional Recovery in Heart Grafts. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.J.; Hatami, S.; Freed, D.H. Thoracic Organ Machine Perfusion: A Review of Concepts with a Focus on Reconditioning Therapies. Front. Transplant. 2023, 2, 1060992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Ambrose, E.; Müller, A.; Li, Y.; Le, H.; Thliveris, J.; Arora, R.C.; Lee, T.W.; Dixon, I.M.C.; Tian, G.; et al. Avoidance of Profound Hypothermia During Initial Reperfusion Improves the Functional Recovery of Hearts Donated After Circulatory Death. Am. J. Transplant. 2016, 16, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egle, M.; Mendez-Carmona, N.; Segiser, A.; Graf, S.; Siepe, M.; Longnus, S. Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion Improves Vascular and Contractile Function by Preserving Endothelial Nitric Oxide Production in Cardiac Grafts Obtained with Donation After Circulatory Death. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S.G.; La Muraglia, G.M.; Madariaga, M.L.L.; Titus, J.S.; Selig, M.K.; Farkash, E.A.; Allan, J.S.; Anderson, L.M.; Madsen, J.C. Preservation of Donor Hearts Using Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion. Ann. Transplant. 2014, 19, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, R.; Lim, Y.W.; Choong, J.W.; Esmore, D.S.; Salamonsen, R.F.; McLean, C.; Forbes, J.; Bailey, M.; Rosenfeldt, F.L. Low-Flow Hypothermic Crystalloid Perfusion Is Superior to Cold Storage During Prolonged Heart Preservation. Transplant. Proc. 2014, 46, 3309–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatte, H.S.; Rousou, L.; Hussaini, B.E.; Lu, X.G.; Treanor, P.R.; Khuri, S.F. Development and Evaluation of a Novel Solution, Somah, for the Procurement and Preservation of Beating and Nonbeating Donor Hearts for Transplantation. Circulation 2009, 120, 1704–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowalekar, S.K.; Cao, H.; Lu, X.G.; Treanor, P.R.; Thatte, H.S. Subnormothermic Preservation in Somah: A Novel Approach for Enhanced Functional Resuscitation of Donor Hearts for Transplant. Am. J. Transplant. 2014, 14, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, H.C.; Iyer, A.; Connellan, M.; Scheuer, S.; Villanueva, J.; Gao, L.; Hicks, M.; Harkness, M.; Soto, C.; Dinale, A.; et al. Outcomes of Donation After Circulatory Death Heart Transplantation in Australia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, S.; Page, A.; Axell, R.; Berman, M.; Hernández-Sánchez, J.; Colah, S.; Parizkova, B.; Valchanov, K.; Dunning, J.; Pavlushkov, E.; et al. Outcome after Heart Transplantation from Donation after Circulatory-Determined Death Donors. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardehali, A.; Esmailian, F.; Deng, M.; Soltesz, E.; Hsich, E.; Naka, Y.; Mancini, D.; Camacho, M.; Zucker, M.; Leprince, P.; et al. Ex-Vivo Perfusion of Donor Hearts for Human Heart Transplantation (PROCEED II): A Prospective, Open-Label, Multicentre, Randomised Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2577–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.A.; Banner, N.R.; Rushton, S.; Simon, A.R.; Berry, C.; Al-Attar, N. ISHLT Primary Graft Dysfunction Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcome: A UK National Study. Transplantation 2019, 103, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, T.P.; Wei, C.; Lin, R.; Bethea, B.T.; Barreiro, C.J.; Amado, L.; Gage, F.; Hare, J.; Baumgartner, W.A.; Conte, J.V. Impact of 24 h Continuous Hypothermic Perfusion on Heart Preservation by Assessment of Oxidative Stress. Clin. Transplant. 2004, 18, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; MacGowan, G.A.; Ali, S.; Dark, J.H. Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: The Past, the Present, and the Future. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2021, 40, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.D.; Patel, M.; Hosgood, S.A.; Nicholson, M.L. Lowering Perfusate Temperature From 37 °C to 32 °C Diminishes Function in a Porcine Model of Ex Vivo Kidney Perfusion. Transplant. Direct 2017, 3, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.X.; Yin, X.M. Mitophagy: Mechanisms, Pathophysiological Roles, and Analysis. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; James, A.M.; Work, L.M.; Saeb-Parsy, K.; Frezza, C.; Krieg, T.; Murphy, M.P. A Unifying Mechanism for Mitochondrial Superoxide Production during Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, D.M.; Hausenloy, D.J. Myocardial Reperfusion Injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCully, J.D.; Wakiyama, H.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Jones, M.; Levitsky, S. Differential Contribution of Necrosis and Apoptosis in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H1923–H1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Ruaengsri, C.; Guenthart, B.A.; Shudo, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, M.R.; MacArthur, J.W.; Hiesinger, W.; Woo, Y.J. Beating Heart Transplant Procedures Using Organs from Donors with Circulatory Death. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e241828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernryd, V.; Stehlik, J.; Metzsch, C.; Lund, L.H.; Gustav Smith, J.; Andersson, B.; Perez, R.; Nilsson, J. Donor Age and Ischemic Time in Heart Transplantation—Implications for Organ Preservation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 44, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, T.; Jász, D.K.; Baráth, B.; Poles, M.Z.; Boros, M.; Hartmann, P. Mitochondrial Consequences of Organ Preservation Techniques during Liver Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S.G.; La Muraglia, G.M.; Madariaga, M.L.L.; Titus, J.S.; Selig, M.K.; Farkash, E.A.; Allan, J.S.; Anderson, L.M.; Madsen, J.C. Twelve-Hour Hypothermic Machine Perfusion for Donor Heart Preservation Leads to Improved Ultrastructural Characteristics Compared to Conventional Cold Storage. Ann. Transplant. 2015, 20, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasian, S.M.; Galagudza, M.M.; Dmitriev, Y.V.; Karpov, A.A.; Vlasov, T.D. Preservation of the Donor Heart: From Basic Science to Clinical Studies. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 20, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.A.; Das De, S.; Spadaccio, C.; Berry, C.; Al-Attar, N. An Overview of Different Methods of Myocardial Protection Currently Employed Peri-Transplantation. Vessel Plus 2017, 1, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Hasanally, D.; Mundt, P.; Li, Y.; Xiang, B.; Klein, J.; Müller, A.; Ambrose, E.; Ravandi, A.; Arora, R.C.; et al. A Whole Blood-Based Perfusate Provides Superior Preservation of Myocardial Function during Ex Vivo Heart Perfusion. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arni, S.; Maeyashiki, T.; Citak, N.; Opitz, I.; Inci, I. Subnormothermic Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Temperature Improves Graft Preservation in Lung Transplantation. Cells 2021, 10, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashigawa, J.; Zuckermann, A.; Macdonald, P.; Leprince, P.; Esmailian, F.; Luu, M.; Mancini, D.; Patel, J.; Razi, R.; Reichenspurner, H.; et al. Report from a Consensus Conference on Primary Graft Dysfunction after Cardiac Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2014, 33, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, R.J.; Wong, N.; Liu, D.H.; Chua, C.; William, J.; Tee, S.L.; Sata, Y.; Bergin, P.; Hare, J.; Leet, A.; et al. Vasoplegia Following Orthotopic Heart Transplantation: Prevalence, Predictors and Clinical Outcomes. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.J.; Iribarne, A.; Hong, K.N.; Ramlawi, B.; Chen, J.M.; Takayama, H.; Mancini, D.M.; Naka, Y. Factors Associated with Primary Graft Failure after Heart Transplantation. Transplantation 2010, 90, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Masa, M.J.; González-Vílchez, F.; Almenar-Bonet, L.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Manito-Lorite, N.; Sobrino-Márquez, J.M.; Gómez-Bueno, M.; Delgado-Jiménez, J.F.; Pérez-Villa, F.; Brossa Loidi, V.; et al. Cold Ischemia >4 Hours Increases Heart Transplantation Mortality. An Analysis of the Spanish Heart Transplantation Registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 319, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGiffin, D.C.; Kure, C.E.; Macdonald, P.S.; Jansz, P.C.; Emmanuel, S.; Marasco, S.F.; Doi, A.; Merry, C.; Larbalestier, R.; Shah, A.; et al. Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion (HOPE) Safely and Effectively Extends Acceptable Donor Heart Preservation Times: Results of the Australian and New Zealand Trial. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, J.N.; Patel, C.B.; DeVore, A.D.; Bryner, B.S.; Casalinova, S.; Shah, A.; Smith, J.W.; Fiedler, A.G.; Daneshmand, M.; Silvestry, S.; et al. Transplantation Outcomes with Donor Hearts after Circulatory Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenderich, G.; El-Banayosy, A.; Rosengard, B.; Tsui, S.; Wallwork, J.; Hetzer, R.; Koerfer, R.; Hassanein, W. 10: Prospective Multi-Center European Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Performance of the Organ Care System for Heart Transplants (PROTECT). J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2007, 26, S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurry, K.; Jeevanandam, V.; Mihaljevic, T.; Couper, G.; Elanwar, M.; Saleh, H.; Ardehali, A. 294: Prospective Multi-Center Safety and Effectiveness Evaluation of the Organ Care System Device for Cardiac Use (PROCEED). J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2008, 27, S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, J.N.; Patel, C.B.; DeVore, A.D.; Casalinova, S.; Koomalsingh, K.J.; Shah, A.S.; Anyanwu, A.C.; D’Alessandro, D.A.; Mudy, K.; Sun, B.; et al. Increasing Utilization of Extended Criteria Donor Hearts for Transplantation: The OCS Heart EXPAND Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, F.; Lebreton, G.; Para, M.; Michel, S.; Schramm, R.; Begot, E.; Vandendriessche, K.; Kamla, C.; Gerosa, G.; Berman, M.; et al. Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion of the Donor Heart in Heart Transplantation: The Short-Term Outcome from a Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Multicentre Clinical Trial. Lancet 2024, 404, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, M.A. Comments on Recipient Outcomes with Extended Criteria Donors Using Advanced Heart Preservation: An Analysis of the GUARDIAN-Heart Registry. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1914–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, H.J.; Kobashigawa, J.A.; Aintablian, T.; Ramzy, D.; Kittleson, M.M.; Esmailian, F. Effects of Older Donor Age and Cold Ischemic Time on Long-Term Outcomes of Heart Transplantation. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2018, 45, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.J.; Chen, J.M.; Sorabella, R.A.; Martens, T.P.; Garrido, M.; Davies, R.R.; George, I.; Cheema, F.H.; Mosca, R.S.; Mital, S.; et al. The Effect of Ischemic Time on Survival after Heart Transplantation Varies by Donor Age: An Analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing Database. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 133, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.L.; Wilhelm, S.K.; Stephan, C.; Urrea, K.A.; Palacio, D.P.; Bartlett, R.H.; Drake, D.H.; Rojas-Pena, A. Extending Heart Preservation to 24 h with Normothermic Perfusion. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1325169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See Hoe, L.E.; Bassi, G.L.; Wildi, K.; Passmore, M.R.; MBiomedSc, M.B.; Sato, K.; Heinsar, S.; Ainola, C.; Bartnikowski, N.; Wilson, E.S.; et al. Donor Heart Ischemic Time Can Be Extended to 8 Hours Using Hypothermic Machine Perfusion in Sheep. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, W.H.; Zellos, L.; Tyrrell, T.A.; Healey, N.A.; Crittenden, M.D.; Birjiniuk, V.; Khuri, S.F.; Rao, V.; Rajaii-Khorasani, A. Continuous Perfusion of Donor Hearts in the Beating State Extends Preservation Time and Improves Recovery of Function. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 116, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahanas, J.M.; Witer, L.J.; Alghanem, F.; Bryner, B.S.; Iyengar, A.; Hirschl, J.R.; Hoenerhoff, M.J.; Potkay, J.A.; Bartlett, R.H.; Rojas-Pena, A.; et al. Achieving 12 Hour Normothermic Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: An Experience of 40 Porcine Hearts. ASAIO J. 2016, 62, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, G.; Du, J.; Gao, B.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Z.; Hu, S.; Ji, B. Development and Evaluation of Heartbeat: A Machine Perfusion Heart Preservation System. Artif. Organs 2017, 41, E240–E250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, N.L.; Shah, A.; Vincent, V.; Wright, B.; Wood, C.; Pavey, W.; Cokis, C.; Chih, S.; Dembo, L.; Larbalestier, R. Successful Heart Transplant after Ten Hours Out-of-Body Time Using the TransMedics Organ Care System. Heart Lung Circ. 2015, 24, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnelas, R.; Kobashigawa, J.A. Ex Vivo Normothermic Perfusion in Heart Transplantation: A Review of the TransMedics® Organ Care System. Future Cardiol. 2022, 18, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, S.; Paskevicius, A.; Liao, Q.; Sjöberg, T. Safe Orthotopic Transplantation of Hearts Harvested 24 Hours after Brain Death and Preserved for 24 Hours. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2016, 50, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, M.; Peng, L.P.; Liu, M. Organ Preservation: From the Past to the Future. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, C.; Michel, J.; Christofi, M.; Wilson, S.H.; Granger, E.; Cropper, J.; Dhital, K.; Macdonald, P. Ex Vivo Coronary Angiographic Evaluation of a Beating Donor Heart. Circulation 2014, 130, e341–e343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Tsui, S.; Huber, J.; Lin, R.; Poggio, E.C.; Ardehali, A. 19: Serum Lactate Is a Highly Sensitive and Specific Predictor of Post Cardiac Transplant Outcomes Using the Organ Care System. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2009, 28, S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounatidis, D.; Brozou, V.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Pantos, C.; Lourbopoulos, A.; Mourouzis, I. Donor Heart Preservation: Current Knowledge and the New Era of Machine Perfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, S.; White, C.W.; Ondrus, M.; Qi, X.; Buchko, M.; Himmat, S.; Lin, L.; Cameron, K.; Nobes, D.; Chung, H.J.; et al. Normothermic Ex Situ Heart Perfusion in Working Mode: Assessment of Cardiac Function and Metabolism. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 2019, e58430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellner, B.; Xin, L.; Pinto Ribeiro, R.V.; Bissoondath, V.; Adamson, M.B.; Yu, F.; Lu, P.; Paradiso, E.; Mbadjeu Hondjeu, A.R.; Simmons, C.A.; et al. The Implementation of Physiological Afterload during Ex Situ Heart Perfusion Augments Prediction of Posttransplant Function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H25–H33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissenbacher, A.; Vrakas, G.; Nasralla, D.; Ceresa, C.D.L. The Future of Organ Perfusion and Re-Conditioning. Transpl. Int. 2019, 32, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, M.; Torrado, J.F.; Mangino, M.J.; Toldo, S. Temperature and Flow Rate Limit the Optimal Ex-Vivo Perfusion of the Heart—An Experimental Study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, T.; Guariento, A.; Doulamis, I.P.; Kido, T.; Regan, W.L.; Saeed, M.; Hoganson, D.M.; Emani, S.M.; Del Nido, P.J.; McCully, J.D.; et al. A Multi-Mode System for Myocardial Functional and Physiological Assessment during Ex Situ Heart Perfusion. J. Extra Corpor. Technol. 2020, 52, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Ambrose, E.; Müller, A.; Li, Y.; Le, H.; Hiebert, B.; Arora, R.; Lee, T.W.; Dixon, I.; Tian, G.; et al. Assessment of Donor Heart Viability during Ex Vivo Heart Perfusion. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarelli, C. Preparing the Future of Organ Banking in Heart Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2025, 44, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, D.E.; Karimov, J.H.; Amarelli, C. Editorial: Graft Preservation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1478730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishawi, M.; Roan, J.N.; Milano, C.A.; Daneshmand, M.A.; Schroder, J.N.; Chiang, Y.; Lee, F.H.; Brown, Z.D.; Nevo, A.; Watson, M.J.; et al. A Normothermic Ex Vivo Organ Perfusion Delivery Method for Cardiac Transplantation Gene Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; O’Brien, T.; Jeppsson, A.; Fitzpatrick, L.A.; Yap, J.; Tazelaar, H.D.; McGregor, C.G.A. Influence of Temperature on Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Transfer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1998, 13, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruixing, Y.; Dezhai, Y.; Hai, W.; Kai, H.; Xianghong, W.; Yuming, C. Intramyocardial Injection of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Improves Cardiac Performance and Inhibits Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2007, 9, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, S.; Xue, S.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, S.; Cui, L.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y. Blockade of Inflammation and Apoptosis Pathways by SiRNA Prolongs Cold Preservation Time and Protects Donor Hearts in a Porcine Model. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 9, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz-Icöz, S.; Li, S.; Hüttner, R.; Ruppert, M.; Radovits, T.; Loganathan, S.; Sayour, A.A.; Brlecic, P.; Lasitschka, F.; Karck, M.; et al. Hypothermic Perfusion of Donor Heart with a Preservation Solution Supplemented by Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2019, 38, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Längin, M.; Mayr, T.; Reichart, B.; Michel, S.; Buchholz, S.; Guethoff, S.; Dashkevich, A.; Baehr, A.; Egerer, S.; Bauer, A.; et al. Consistent Success in Life-Supporting Porcine Cardiac Xenotransplantation. Nature 2018, 564, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, B.P.; Goerlich, C.E.; Singh, A.K.; Rothblatt, M.; Lau, C.L.; Shah, A.; Lorber, M.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.K.; Hong, S.N.; et al. Genetically Modified Porcine-To-Human Cardiac Xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuth, J.; Falter, F.; Pinto Ribeiro, R.V.; Badiwala, M.; Meineri, M. New Strategies to Expand and Optimize Heart Donor Pool: Ex Vivo Heart Perfusion and Donation After Circulatory Death: A Review of Current Research and Future Trends. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 128, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, O.; Bottio, T.; Caraffa, R.; Carrozzini, M.; Guariento, A.; Bejko, J.; Fedrigo, M.; Castellani, C.; Toscano, G.; Lorenzoni, G.; et al. Marginal versus Standard Donors in Heart Transplantation: Proper Selection Means Heart Transplant Benefit. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Gao, L.; Doyle, A.; Rao, P.; Cropper, J.R.; Soto, C.; Dinale, A.; Kumarasinghe, G.; Jabbour, A.; Hicks, M.; et al. Normothermic Ex Vivo Perfusion Provides Superior Organ Preservation and Enables Viability Assessment of Hearts from DCD Donors. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyev, R.; Bekbossynov, S.; Nurmykhametova, Z. Sixteen-Hour Ex Vivo Donor Heart Perfusion During Long-Distance Transportation for Heart Transplantation. Artif. Organs 2019, 43, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeter, R.; Pasic, M.; Hübler, M.; Dandel, M.; Hiemann, N.; Kemper, D.; Wellnhofer, E.; Hetzer, R.; Knosalla, C. Extended Donor Criteria in Heart Transplantation: 4-Year Results of the Experience with the Organ Care System. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 62, SC44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.; Cheong, C.; Fulton, M.; Shah, M.; Doyle, A.; Gao, L.; Villanueva, J.; Soto, C.; Hicks, M.; Connellan, M.; et al. Outcome After Warm Machine Perfusion (WMP) Recovery of Marginal Brain Dead (MBD) and Donation After Circulatory Death (DCD) Heart Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, S45–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Sáez, D.; Zych, B.; Mohite, P.N.; Sabashnikov, A.; Patil, N.P.; Popov, A.; Zeriouh, M.; Bowles, C.T.; Hards, R.; Hedger, M.; et al. LVAD Bridging to Heart Transplantation with Ex Vivo Allograft Preservation Shows Significantly Improved: Outcomes: A New Standard of Care? J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Ali, A.; Hasanally, D.; Xiang, B.; Li, Y.; Mundt, P.; Lytwyn, M.; Colah, S.; Klein, J.; Ravandi, A.; et al. A Cardioprotective Preservation Strategy Employing Ex Vivo Heart Perfusion Facilitates Successful Transplant of Donor Hearts after Cardiocirculatory Death. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2013, 32, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, A.; Gao, L.; Doyle, A.; Rao, P.; Jayewardene, D.; Wan, B.; Kumarasinghe, G.; Jabbour, A.; Hicks, M.; Jansz, P.C.; et al. Increasing the Tolerance of DCD Hearts to Warm Ischemia by Pharmacological Postconditioning. Am. J. Transplant. 2014, 14, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouckaert, J.; Vandendriessche, K.; Degezelle, K.; Van de Voorde, K.; De Burghgraeve, F.; Desmet, L.; Vlasselaers, D.; Ingels, C.; Dauwe, D.; De Troy, E.; et al. Successful Clinical Transplantation of Hearts Donated after Circulatory Death Using Direct Procurement Followed by Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion: A Report of the First 3 Cases. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1907–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilvers, N.J.; Vandendriessche, K.; Moeslund, N.; Berman, M.; Brouckaert, J.; Butt, T.; Cardoso, B.; Cools, B.; Crossland, D.; Dark, J.; et al. HOPE for Children: Successful Pediatric DCD Heart Transplantation Using Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowalekar, S.K.; Lu, X.G.; Thatte, H.S. Further Evaluation of Somah: Long-Term Preservation, Temperature Effect, and Prevention of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat Hearts Harvested After Cardiocirculatory Death. Transplant. Proc. 2013, 45, 3192–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annema, C.; De Smet, S.; Castle, E.M.; Overloop, Y.; Klaase, J.M.; Janaudis-Ferreira, T.; Mathur, S.; Kouidi, E.; Perez Saez, M.J.; Matthys, C.; et al. European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT) Consensus Statement on Prehabilitation for Solid Organ Transplantation Candidates. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, M.I.; Bonaccorsi Riani, E.; Giorgakis, E.; Kaisar, M.E.; Patrono, D.; Weissenbacher, A. Organ Reconditioning and Machine Perfusion in Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, I.; Canizares, S.; Devos, L.; Strom, C.; Battula, N.; Eckhoff, D.E.; Martins, P.N. Machine Perfusion Organ Preservation: Highlights from the American Transplant Congress 2023. Artif. Organs 2024, 48, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Prichard, R.A.; Connellan, M.B.; Dhital, K.K.; Macdonald, P.S. Long Distance Heart Transplantation: A Tale of Two Cities. Intern. Med. J. 2017, 47, 1202–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijauskaite, K.; Veraza, R.J.; Lopez, R.P.; Maxwell, Z.; Cano, I.; Cisneros, E.E.; Jessop, I.J.; Basurto, M.; Lamberson, G.; Watt, M.D.; et al. Novel Portable Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Preservation Device Enhances Cardiac Viability of Donated Human Hearts. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1376101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, M.; Garg, P.; Yazji, J.H.; Wadiwala, I.J.; Alamouti-fard, E.; Hussain, M.W.A.; Elawady, M.S.; Jacob, S. Is the Organ Care System (OCS) Still the First Choice With Emerging New Strategies for Donation After Circulatory Death (DCD) in Heart Transplant? Cureus 2022, 14, e26281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, J.; Öchsner, M.; Shah, A.; Hoffman, J.; Vilchez, F.G.; Garrido, I.; Royo-Villanova, M.; Domínguez-Gil, B.; Smith, D.; James, L.; et al. The International Experience of In-Situ Recovery of the DCD Heart: A Multicentre Retrospective Observational Study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, A.; Shemie, S.D.; Large, S.; Healey, A.; Baker, A.; Badiwala, M.; Berman, M.; Butler, A.J.; Chaudhury, P.; Dark, J.; et al. Maintaining the Permanence Principle for Death during in Situ Normothermic Regional Perfusion for Donation after Circulatory Death Organ Recovery: A United Kingdom and Canadian Proposal. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, B.; Moazami, N.; Wall, S.; Carillo, J.; Kon, Z.; Smith, D.; Walsh, B.C.; Caplan, A. Ethical and Logistical Concerns for Establishing NRP-CDCD Heart Transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffini, M.; Gerosa, G.; Luciani, G.B.; Pacini, D.; Russo, C.F.; Rinaldi, M.; Terzi, A.; Pelenghi, S.; Luzi, G.; Zanatta, P.; et al. Heart Transplantation in Controlled Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death: The Italian Experience. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Nykanen, A.I.; Beroncal, E.; Brambate, E.; Mariscal, A.; Michaelsen, V.; Wang, A.; Kawashima, M.; Ribeiro, R.V.P.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Successful 3-Day Lung Preservation Using a Cyclic Normothermic Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Strategy. EBioMedicine 2022, 83, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Preservation Method | Study Name | Sample Size | Mean Preservation Time | PGD Incidence (MP vs. SCS) | Survival (30-Day) | Primary Endpoint | Key Finding/Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normothermic Machine Perfusion (NMP) | PROTECT I (2007) [76] | 20 transplanted (human) | 222 ± 54 min | Not compared | 100% | Safety & Performance | Established initial safety and feasibility of OCS for transport. |

| PROCEED I (2008) [77] | 13 transplanted (human) | Not reported | 15.4% | 84.6% | Safety & Effectiveness | Established safety, including in higher-risk MCS patients. | |

| PROCEED II (2015) [53] | N = 130 (NMP: 62/67; SCS: 63) (human) | 211 min | 12% vs. 14% | 94% vs. 97% | 30-day survival | Established non-inferiority of OCS to SCS for standard-criteria donors. | |

| OCS Heart EXPAND (2024) [78] | 150 transplanted (human) | Not reported | 6.7% (severe PGD) | 96.6% | Composite of 30-day survival & absence of severe PGD | High utilization (86.7%) of extended-criteria donors with excellent survival, confirming NMP’s value in expanding the donor pool. | |

| Hypothermic Machine Perfusion (HMP) | NIHP2019 trial (2024) [79] | N = 203 (HMP: 100; SCS: 103) (human) | Not yet published | 11% vs. 28% | No significant difference | Composite of major adverse cardiac transplant events | HMP significantly reduced PGD by 61% and major adverse cardiac events. |

| Australian and New Zealand Trial (2024) [74] | N = 44 (HMP: 22; SCS: 22) (human) | 414 min | 5% vs. 19% | 100% | Severe PGD incidence | HMP safely extended preservation times to ~7 h and significantly reduced severe PGD. | |

| Subnormothermic Machine Perfusion (SNMP) | Somah Solution Preclinical Study (2014) [31] | Porcine model | 5 h | Not applicable | Not applicable | Metabolic stability | Demonstrated superior ATP retention and reduced ischemic markers vs. SCS in an animal model. |

| SNOP for Neonatal and Pediatric Hearts (2023) [33] | Piglet model | 10 h | Not applicable | Not applicable | Hemodynamic stability | Showed the feasibility of extended (10-h) preservation for pediatric-sized hearts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Georghiou, P.; Georghiou, G.P.; Amarelli, C.; Berman, M. Optimizing Temperature in Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Novel Methods in Heart Transplantation. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010025

Georghiou P, Georghiou GP, Amarelli C, Berman M. Optimizing Temperature in Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Novel Methods in Heart Transplantation. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorghiou, Panos, Georgios P. Georghiou, Cristiano Amarelli, and Marius Berman. 2026. "Optimizing Temperature in Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Novel Methods in Heart Transplantation" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010025

APA StyleGeorghiou, P., Georghiou, G. P., Amarelli, C., & Berman, M. (2026). Optimizing Temperature in Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A Comparative Review of Traditional and Novel Methods in Heart Transplantation. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010025