Females and Exercise Capacity Impairment in Heart Failure: A Sex-Focused Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Baseline Assessment

2.3. Psychosocial Evaluation

2.4. Submaximal Exercise Capacity Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

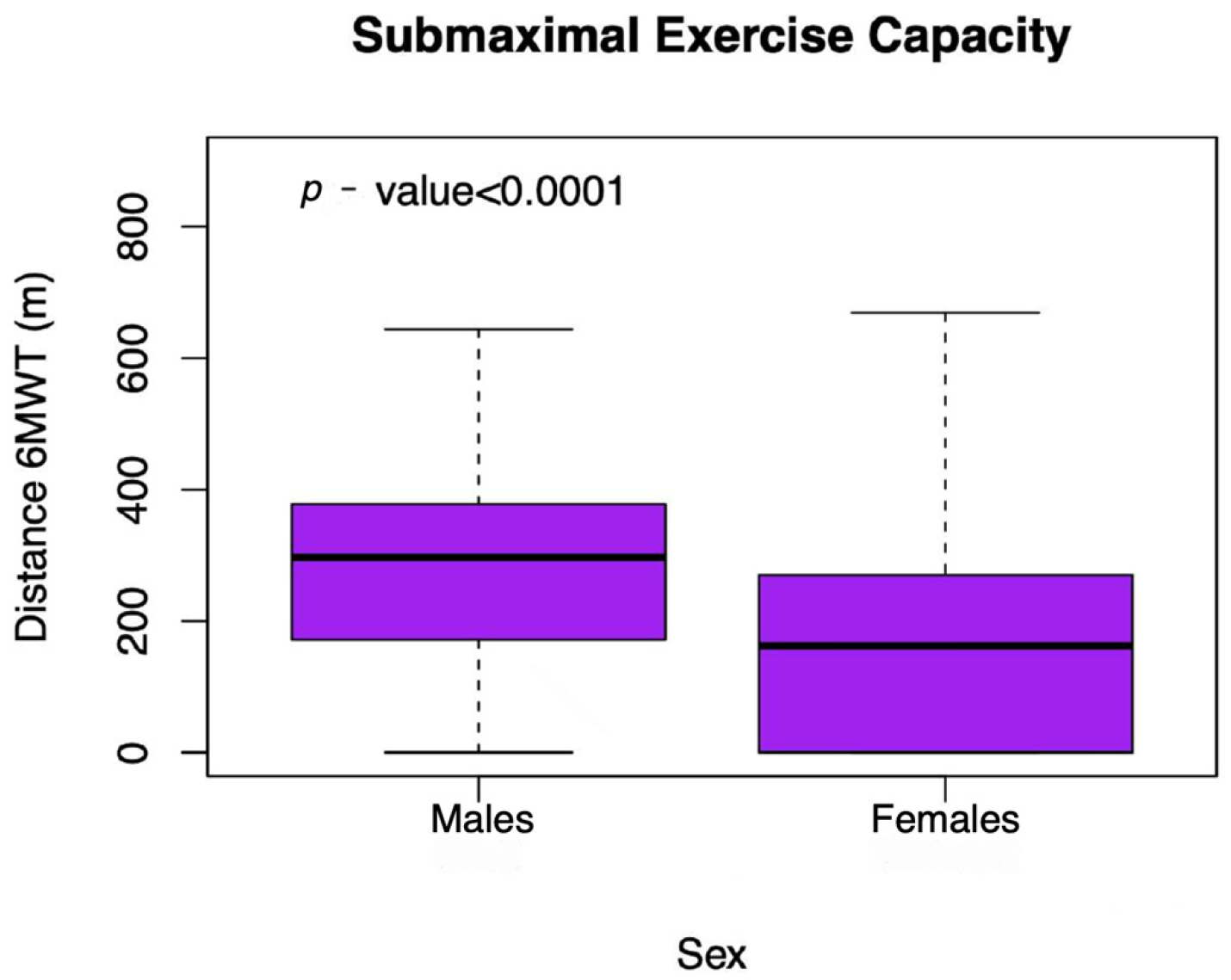

3.1. Determinants of Submaximal Exercise Capacity in Unadjusted Analyses

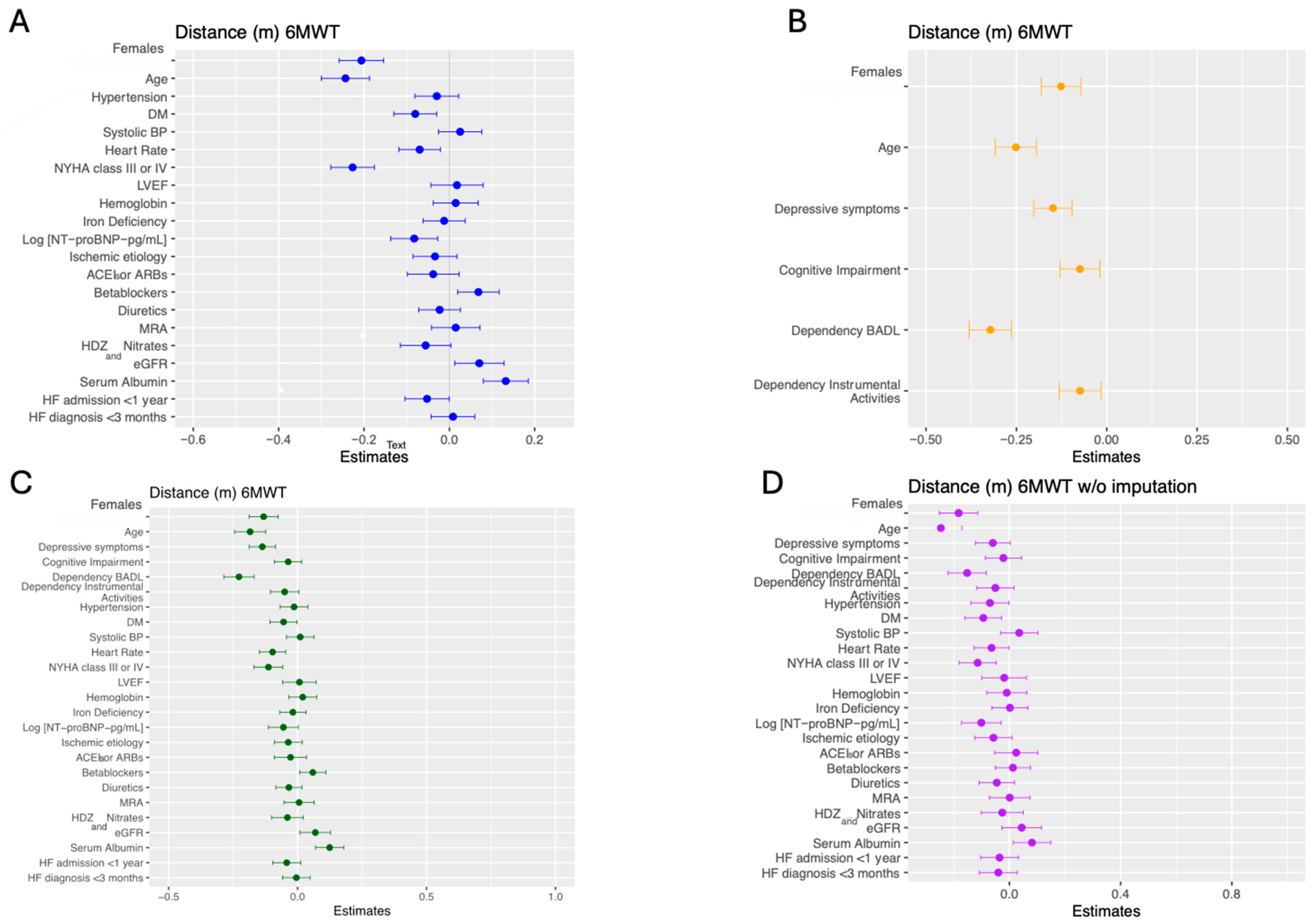

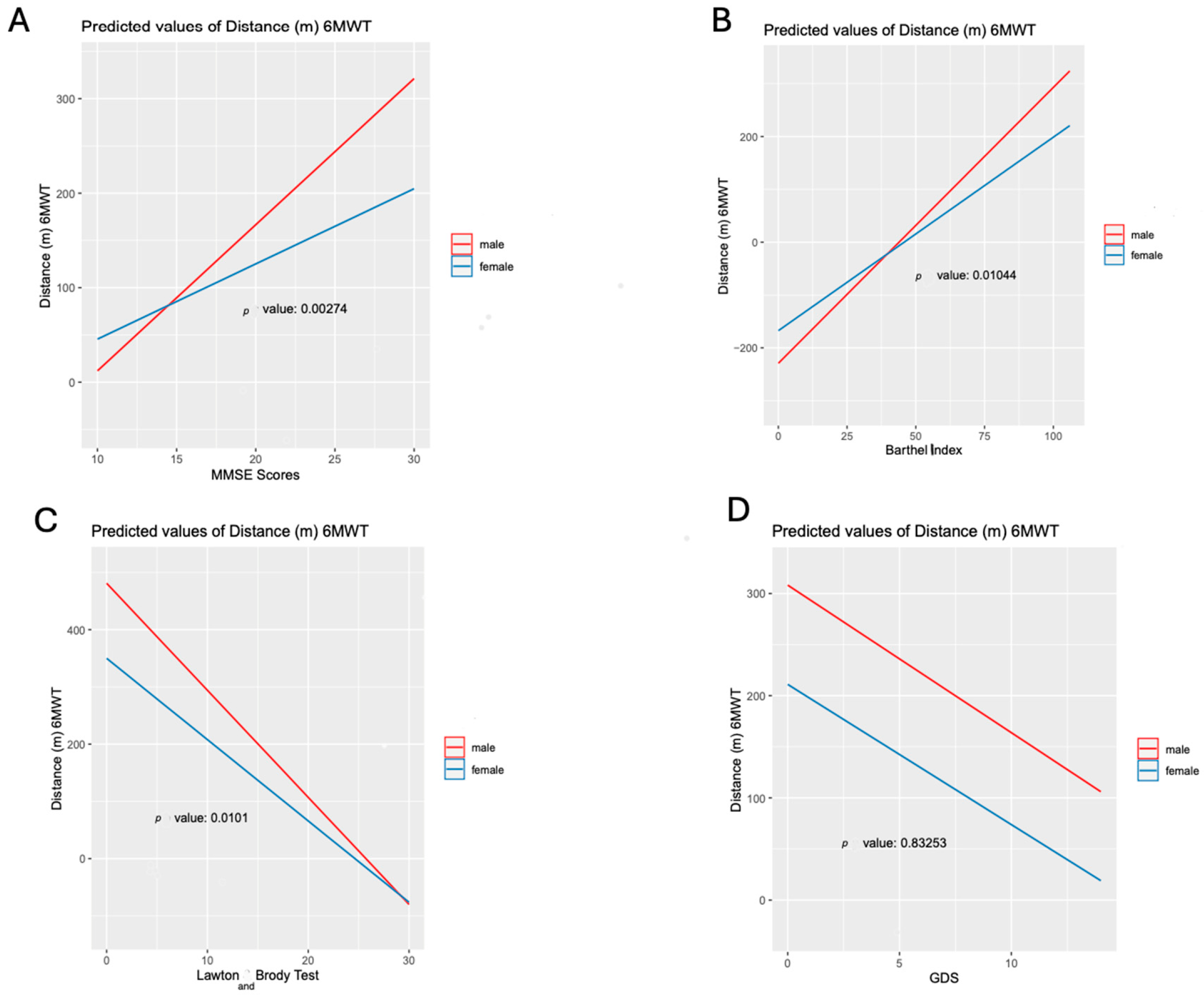

3.2. The Role of Sex in Models Adjusted for Clinical Determinants

3.3. The Role of Sex in Models Adjusted for Psycho-Functional Determinants

3.4. The Role of Sex in Comprehensive Adjusted Models Including Clinical and Psychosocial Determinants

3.5. The Role of Sex in Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADLs | Activities of Daily Living |

| CHF | Chronic Heart Failure |

| DAMOCLES | Definition of the neuro-hormonal Activation, Myocardial function, genOmic expression, and CLinical outcomes in hEart failure patients |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| GDS | 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination questionnaire |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PROMs | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SEC | Submaximal Exercise Capacity |

| SPMSQ | Short Portable Mental State Questionnaire |

| 6MWT | 6-Minute Walk Test |

References

- Farré, N.; Vela, E.; Clèries, M.; Bustins, M.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Enjuanes, C.; Moliner, P.; Ruiz, S.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Comín-Colet, J. Real world heart failure epidemiology and outcome: A population-based analysis of 88,195 patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Capdevila, C.; Vela, E.; Cleries, M.; Bilal, U.; Garcia-Altes, A.; Enjuanes, C.; Garay, A.; Yun, S.; Farre, N.; et al. Individual income, mortality and healthcare resource use in patients with chronic heart failure living in a universal healthcare system: A population-based study in Catalonia, Spain. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 277, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moliner, P.; Comin-Colet, J. Iron deficiency and supplementation therapy in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, F.; Zotter-Tufaro, C.; Kammerlander, A.A.; Aschauer, S.; Binder, C.; Mascherbauer, J. Sex-related differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, E.A.; Marshall, R.J. Cardiovascular Disease in Females. Prim. Care-Clin. Off. Pract. 2018, 45, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Khalaf, S. Heart Failure in Females. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 2017, 13, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, A.; Tapia, J.; Anguita, M.; Formiga, F.; Almenar, L.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G. Sex differences in health-related quality of life in patients with systolic heart failure: Results of the vida multicenter study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, J.; Basalo, M.; Enjuanes, C.; Calero, E.; José, N.; Ruíz, M.; Calvo, E.; Garcimartín, P.; Moliner, P.; Hidalgo, E. Psychosocial factors partially explain sex differences in health-related quality of life in heart failure patients. ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsi, S.; Bougiakli, M.; Bechlioulis, A.; Kotsia, A.; Michalis, L.K.; Naka, K.K. 6-minute walking test: A useful tool in the management of heart failure patients. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 13, 1753944719870084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjuanes, C.; Bruguera, J.; Grau, M.; Cladellas, M.; Gonzalez, G.; Meroño, O.; Moliner-Borja, P.; Verdú, J.M.; Farré, N.; Comín-Colet, J. Iron Status in Chronic Heart Failure: Impact on Symptoms, Functional Class and Submaximal Exercise Capacity. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2016, 69, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comín-Colet, J.; Enjuanes, C.; González, G.; Torrens, A.; Cladellas, M.; Meroño, O.; Ribas, N.; Ruiz, S.; Gómez, M.; Verdú, J.M.; et al. Iron deficiency is a key determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure regardless of anaemia status. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coma, M.; González-Moneo, M.J.; Enjuanes, C.; Velázquez, P.P.; Espargaró, D.B.; Pérez, B.A.; Tajes, M.; Garcia-Elias, A.; Farré, N.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; et al. Effect of permanent atrial fibrillation on cognitive function in patients with chronic heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 117, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moneo, M.J.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Verdu-Rotellar, J.M.; Cladellas, M.; Bruguera, J.; Quiñones-Ubeda, S.; Enjuanes, C.; Peña-Casanova, J.; Comín-Colet, J. Ischemic aetiology, self-reported frailty, and sex with respect to cognitive impairment in chronic heart failure patients. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.; Gardner, M.; Tsiachristas, A.; Langhorne, P.; Burke, O.; Harwood, R.H.; Conroy, S.P.; Kircher, T.; Somme, D.; Saltvedt, I.; et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD006211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, D.; Oehlberg, K.A.; Katz, I.R.; Stern, M.B. Test characteristics of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in Parkinson disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comín-Colet, J.; Enjuanes, C.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Linas, A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez, P.; González-Robledo, G.; Farré, N.; Moliner-Borja, P.; Ruiz-Bustillo, S.; Bruguera, J. Impact on clinical events and healthcare costs of adding telemedicine to multidisciplinary disease management programmes for heart failure: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 22, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwala, P.; Salzman, S.H. Six-Minute Walk Test: Clinical Role, Technique, Coding, and Reimbursement. Chest 2020, 157, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautmans, I.; Lambert, M.; Mets, T. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: Influence of health status. BMC Geriatr. 2004, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ma, W.; Yang, D.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M.; Cao, X.; Zhang, C.; Luo, X.; He, S.; et al. A prospective study on sex differences in functional capacity, quality of life and prognosis in patients with heart failure. Medicine 2022, 101, e29795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Lau, E. Sex differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: From traditional risk factors to sex-specific risk factors. Females’s Health 2022, 18, 17455057221140209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honigberg, M.C.; Lau, E.S.; Jones, A.D.; Coles, A.; Redfield, M.M.; Lewis, G.D.; Givertz, M.M. Sex Differences in Exercise Capacity and Quality of Life in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Secondary Analysis of the RELAX and NEAT-HFpEF Trials: Sex Differences in HFpEF. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palau, P.; Domínguez, E.; Núñez, J. Sex differences on peak oxygen uptake in heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2019, 6, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Motoki, H.; Suzuki, S.; Fuchida, A.; Takeuchi, T.; Otagiri, K.; Kanai, M.; Kimura, K.; Minamisawa, M.; Yoshie, K.; et al. Sex difference in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Clinical profiles, examinations, and prognosis. Heart Vessel. 2022, 37, 1710–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoto Otero, C.; Conthe Gutiérrez, P. Insuficiencia cardíaca en la mujer. Rasgos diferenciales. Med. Integral 2002, 39, 454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Gebhard, C. Sex medicine: Effects of sex and sex on cardiovascular disease manifestation and outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arosio, B.; Corbi, G.; Davinelli, S.; Giordano, V.; Liccardo, D.; Rapacciuolo, A.; Cannavo, A. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Matter of Estrogens, Ceramides, and Sphingosine 1-Phosphate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, F.; Xie, X.; Chen, X. Reference equations for the six-minute walk distance in the healthy Chinese population aged 18–59 years. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, A.J.; Ahlmen, A.; Rosendorf, J.M.; Romeo, A.A.; Erickson, B.J.; Bishop, M.E. The biology of sex and sport. JBJS Rev. 2020, 8, e0140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, A.L.; Warren, J.L.; Roberts, N.; Meyer, P.; Townsend, N.P.; Kaye, D. Iron deficiency in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2019, 6, e001012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenstein, L.; Remppis, A.; Graham, J.; Schellberg, D.; Sigg, C.; Nelles, M. Sex and age related predictive value of walk test in heart failure: Do anthropometrics matter in clinical practice? Int. J. Cardiol. 2008, 127, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.S.; Cunningham, T.; Hardin, K.M.; Liu, E.; Malhotra, R.; Nayor, M.; Lewis, G.D.; Ho, J.E. Sex Differences in Cardiometabolic Traits and Determinants of Exercise Capacity in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Carotti, M.; Stancati, A.; Grassi, W. Health-related quality of life in older adults with symptomatic hip and knee osteoarthritis: A comparison with matched healthy controls. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2005, 17, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, V.; Caterino, A.L.; Bianco, F.; Caputi, C.G.; Salerni, S.; Sciomer, S.; Maffei, S.; Gallina, S. Depression and cardiovascular disease: The deep blue sea of females’s heart. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moaddab, F.; Ghanbari, A.; Taheri-Ezbarami, Z.; Salari, A.; Kazemnezhad-Leyli, E. Clinical parameters and outcomes in heart failure patients based on sex differences. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 18, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, I.; Kotecha, D.; Chin, K.L.; Mentz, R.J.; von Lueder, T.G. Comorbidities in Heart Failure: Are There Sex Differences? Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2016, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parwani, P.J.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Mamas, M. Representation of females in heart failure trials: Does it matter? Heart 2022, 108, 1508–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Whole Cohort (n = 1069) | Females (n = 457) | Males (n = 612) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Clinical Factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 72 ± 11 | 75 ± 10 | 71± 12 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 124 ± 22 | 124 ± 21 | 124 ± 22 | 0.516 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 734 ± 14 | 75 ± 15 | 73 ± 14 | 0.063 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| I | 140 (13%) | 30 (7%) | 110 (18%) | |

| II | 497 (47%) | 199 (44%) | 298 (49%) | |

| III | 351 (33%) | 183 (40%) | 168 (28%) | |

| IV | 76 (7%) | 43 (9%) | 33 (5%) | |

| HF hospitalisation previous year, n (%) | 883 (83%) | 391 (86%) | 492 (81%) | 0.031 |

| HF diagnosis > 1 year, n (%) | 406 (38%) | 164 (36%) | 242 (40%) | 0.215 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 45 ± 17 | 50 ± 17 | 40 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| HFpEF, n (%) | 636 (60%) | 204 (45%) | 432 (71%) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic etiology of HF, n (%) | 406 (38%) | 116 (25%) | 290 (47%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 859 (80%) | 387 (85%) | 472 (77%) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 494 (46%) | 217 (48%) | 277 (45%) | 0.486 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 276 (26%) | 64 (14%) | 212 (35%) | <0.001 |

| CKD, n (%) | 585 (55%) | 306 (67%) | 279 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 518 (49%) | 234 (51%) | 284 (47%) | 0.120 |

| Iron deficiency, n (%) | 610 (57%) | 278 (62%) | 332 (55%) | 0.029 * |

| Treatments (%) | ||||

| ACEIs or ARBs | 780 (73%) | 333 (73%) | 447 (73%) | 0.992 |

| Beta-blockers | 941 (88%) | 396 (86%) | 545 (89%) | 0.232 |

| MRA | 398 (37%) | 137 (30%) | 261 (42%) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics | 970 (90%) | 427 (93%) | 543 (88%) | 0.009 |

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy | 880 (82%) | 362 (79%) | 518 (84%) | 0.021 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 12.1± 1.7 | 13.1± 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.33 ± 0.60 | 1.24 ± 0.55 | 1.40± 0.63 | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1583 [685–3766] | 1657 [752–3890] | 1516 [620–369] | 0.422 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 ± 0.49 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 0.003 |

| Psycho-functional Factors | ||||

| Barthel index (points) | 92 ± 16 | 88 ± 18 | 94 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| Dependency for basic ADLs, n (%) | 366 (34%) | 216 (54%) | 150 (28%) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe dependency for basic ADLs, n (%) | 264 (24%) | 162 (40%) | 102 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Lawton and Brody test (points) | 13 ± 5 | 14 ± 6 | 12 ± 5 | <0.001 |

| Dependency instrumental activities, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No dependency | 250 (23%) | 73 (17%) | 177 (31%) | |

| Mild dependency | 641 (60%) | 293 (70%) | 348 (62%) | |

| Moderate or severe dependency | 90 (8%) | 55 (13%) | 35 (6%) | |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 344 (32%) | 209 (46%) | 135 (22%) | <0.001 |

| Score in the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), points | 3.6 ± 3.0 | 4.1 ± 3.0 | 3.2 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms, n (%) | 298 (27%) | 161 (41%) | 137 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Fragility criteria + | 635 (59%) | 346 (81%) | 289 (54%) | <0.001 |

| UNIVARIATE | MULTIVARIATE (SPLIT) | MULTIVARIATE (JOINT) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% IC | p-Value | OR | 95% IC | p-Value | OR | 95% IC | p-Value | |

| Disease-related and demographic determinants | |||||||||

| Females, women vs. males | 3.906 | 2.946–5.180 | <0.001 | 3.609 | 2.462–5.291 | <0.001 | 2.681 | 1.709–4.204 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.095 | 1.080–1.110 | <0.001 | 1.072 | 1.053–1.092 | <0.001 | 1.056 | 1.034–1.078 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.997 | 0.991–1.003 | 0.315 | 0.997 | 0.989–1.005 | 0.506 | 0.999 | 0.990–1.008 | 0.846 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 1.015 | 1.006–1.024 | 0.001 | 1.008 | 0.996–1.020 | 0.174 | 1.016 | 1.002–1.030 | 0.028 |

| NYHA functional class, III–IV vs. I–II | 5.464 | 4.016–7.434 | <0.001 | 3.050 | 2.094–4.441 | <0.001 | 1.765 | 1.137–2.740 | 0.011 |

| HF hospitalization previous year | 3.348 | 2.415–4.641 | <0.001 | 1.710 | 1.088–2.688 | 0.020 | 1.497 | 0.903–2.481 | 0.118 |

| HF diagnosis <3 months (recent) | 1.436 | 1.116–1.848 | 0.005 | 1.274 | 0.882–1.840 | 0.197 | 1.343 | 0.878–2.054 | 0.174 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, 1% | 1.018 | 1.011–1.026 | <0.001 | 0.993 | 0.980–1.006 | 0.289 | 0.995 | 0.979–1.010 | 0.499 |

| Ischaemic aetiology | 1.219 | 0.939–1.581 | 0.136 | 1.342 | 0.917–1.965 | 0.130 | 1.432 | 0.925–2.217 | 0.107 |

| Hypertension | 2.996 | 2.199–4.082 | <0.001 | 1.668 | 1.079–2.577 | 0.021 | 1.530 | 0.918–2.550 | 0.102 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.966 | 1.519–2.545 | <0.001 | 1.712 | 1.206–2.430 | 0.003 | 1.435 | 0.960–2.144 | 0.078 |

| Iron deficiency | 1.867 | 1.445–2.413 | <0.001 | 1.035 | 0.730–1.467 | 0.849 | 1.010 | 0.678–1.506 | 0.960 |

| Laboratory and treatment | |||||||||

| ACEIs or ARBs, yes vs. no | 0.459 | 0.337–0.625 | <0.001 | 0.917 | 0.559–1.504 | 0.731 | 0.747 | 0.424–1.316 | 0.313 |

| Beta-blockers, yes vs. no | 0.401 | 0.254–0.632 | <0.001 | 0.490 | 0.272–0.881 | 0.017* | 0.698 | 0.369–1.320 | 0.268 |

| MRA, yes vs. no | 0.595 | 0.460–0.769 | <0.001 | 1.129 | 0.750–1.700 | 0.562 | 1.129 | 0.708–1.802 | 0.609 |

| Diuretics, yes vs. no | 2.847 | 1.867–4.340 | <0.001 | 1.432 | 0.784–2.615 | 0.242 | 1.622 | 0.829–3.174 | 0.157 |

| Hydralazine and nitrate, yes vs. no | 2.294 | 1.628–3.233 | <0.001 | 1.176 | 0.694–1.992 | 0.546 | 0.981 | 0.539–1.785 | 0.949 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.729 | 0.678–0.784 | <0.001 | 0.973 | 0.899–1.052 | 0.490 | 0.968 | 0.879–1.065 | 0.502 |

| logNT-proBNP, log[1pg/mL] | 3.064 | 2.391–3.925 | <0.001 | 1.407 | 0.999–1.980 | 0.050 | 1.294 | 0.871–1.923 | 0.202 |

| eGFR, (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 0.974 | 0.968–0.979 | <0.001 | 0.992 | 0.984–1.000 | 0.049 | 0.993 | 0.984–1.001 | 0.096 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 0.204 | 0.148–0.281 | <0.001 | 0.476 | 0.326–0.694 | <0.001 | 0.459 | 0.294–0.716 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 for each model | - | - | - | 0.415 | |||||

| Psychosocialand demographic determinants | |||||||||

| Sex, women vs. men | - | - | - | 2.226 | 1.537–3.224 | <0.001 | - | - | |

| Age, 1 year | - | - | - | 1.066 | 1.048–1.084 | <0.001 | - | - | |

| Moderate or severe dependency for basic ADLs, yes vs. no | 12.068 | 8.021–18.156 | <0.001 | 6.159 | 3.904–9.716 | <0.001 | 4.837 | 2.877–8.130 | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe dependency instrumental activities, yes vs. no | 5.043 | 3.713–6.849 | <0.001 | 1.806 | 1.229–2.655 | 0.003 | 1.660 | 1.079–2.555 | 0.021 |

| Cognitive impairment, yes vs. no | 4.036 | 2.930–5.558 | <0.001 | 1.675 | 1.106–2.536 | 0.015 | 1.373 | 0.870–2.166 | 0.173 |

| Depressive symptoms, yes vs. no | 2.177 | 1.594–2.973 | <0.001 | 1.409 | 0.948–2.095 | 0.067 | 1.310 | 0.839–2.045 | 0.235 |

| Adjusted R2 for each model | - | 0.318 | 0.483 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorenzo, A.; Ramos-Polo, R.; Lorenzo-Esteller, L.; Lin, X.; Barragan, E.; Aranda, P.; Boixader, È.; Regull, F.; Martín, N.; Ollé, A.; et al. Females and Exercise Capacity Impairment in Heart Failure: A Sex-Focused Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12120494

Lorenzo A, Ramos-Polo R, Lorenzo-Esteller L, Lin X, Barragan E, Aranda P, Boixader È, Regull F, Martín N, Ollé A, et al. Females and Exercise Capacity Impairment in Heart Failure: A Sex-Focused Analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(12):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12120494

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorenzo, Ainhoa, Raúl Ramos-Polo, Laia Lorenzo-Esteller, Xinying Lin, Emma Barragan, Paula Aranda, Èlia Boixader, Foix Regull, Nerea Martín, Ariana Ollé, and et al. 2025. "Females and Exercise Capacity Impairment in Heart Failure: A Sex-Focused Analysis" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 12: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12120494

APA StyleLorenzo, A., Ramos-Polo, R., Lorenzo-Esteller, L., Lin, X., Barragan, E., Aranda, P., Boixader, È., Regull, F., Martín, N., Ollé, A., Llagostera, M., José-Bazán, N., Moliner, P., Enjuanes, C., & Comin-Colet, J. (2025). Females and Exercise Capacity Impairment in Heart Failure: A Sex-Focused Analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(12), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12120494