The Introduction of a New Mobile Driving Unit for a Ventricular Assist Device in a Pediatric Patient (EXCOR Active)

Abstract

1. Introduction

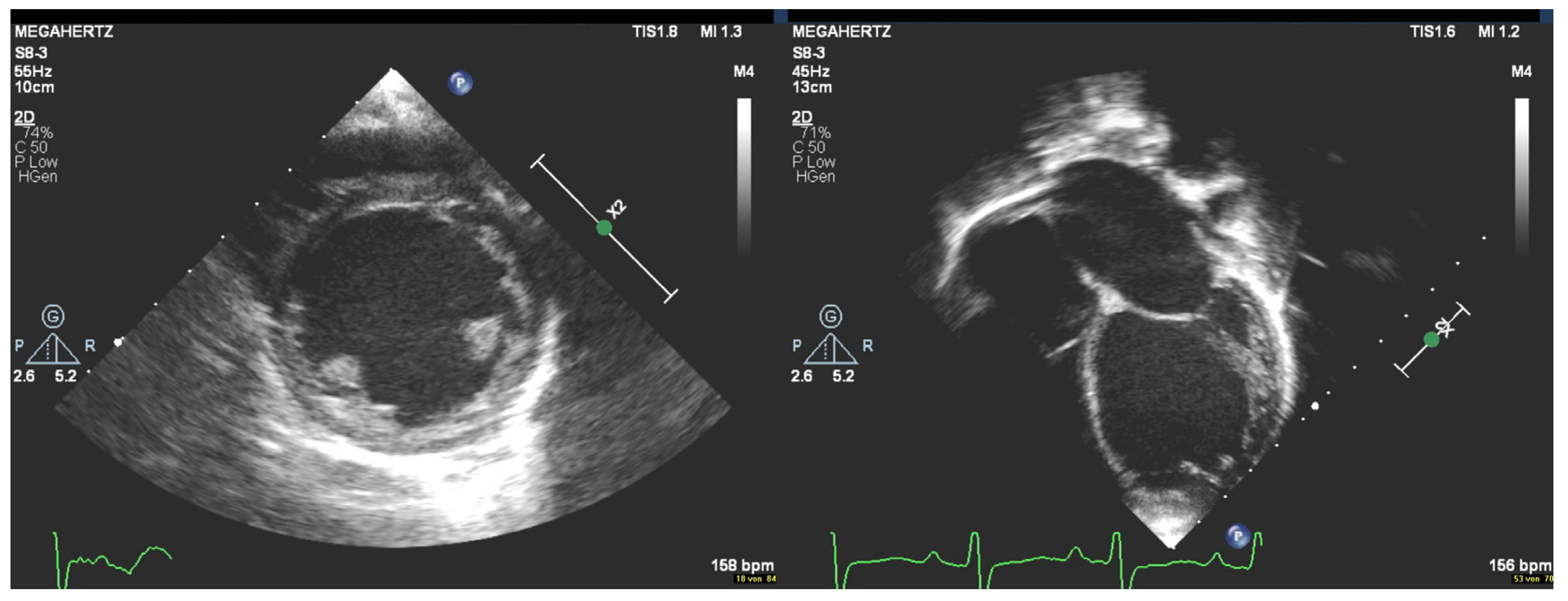

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, D.M.; Yu, S.; Lowery, R.; Ventresco, C.; Cousino, M.K.; St Louis, J.D.; Blume, E.D.; Uzark, K. Self-reported quality of life in children with ventricular assist devices. Pediatr. Transplant. 2022, 26, e14237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, M.; Daneshi, F.; Behzadmehr, R.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Bouya, S.; Raeisi, M. Quality of life of chronic heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot, I.; Marino, B.S. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Heart Failure. In Heart Failure in the Child and Young Adult; Jefferies, J.L., Chang, A.C., Rossano, J.W., Shaddy, R.E., Towbin, J.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger, M.; Vanderpluym, C.; Jeewa, A.; Canter, C.E.; Jansz, P.; Parrino, P.E.; Miera, O.; Schmitto, J.; Mehegan, M.; Adachi, I.; et al. Outpatient Management of Intra-Corporeal Left Ventricular Assist Device System in Children: A Multi-Center Experience. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingräber, R.; Kiesner, M. Real World Experience with an Optimized Control Scheme for a Ventricular Assist Device. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 6, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, B.S.; Marx, M.; Gass, M.; Wiedemann, D.; Michel-Behnke, I. Mechanical circulatory support as bridge to recovery in an 8-year-old girl with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy due to atypical atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia: A case report. Eur. Heart J.-Case Rep. 2024, 8, ytae509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.; Pidborochynski, T.; Ly, D.; Mowat, L.; Freed, D.H.; De Villiers Jonker, I.; Al-Aklabi, M.; Holinski, P.; Anand, V.; Buchholz, H. First North American experience with the Berlin Heart EXCOR Active driver. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1861–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottermann, K.; Dittrich, S.; Dewald, O.; Teske, A.; Kwapil, N.; Bleck, S.; Purbojo, A.; Münch, F. Mobility and freedom of movement: A novel out-of-hospital treatment for pediatric patients with terminal cardiac insufficiency and a ventricular assist device. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1055228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, A.; Palazzini, M.; Trimarchi, G.; Conti, N.; Di Spigno, F.; Gentile, P.; D’Angelo, L.; Garascia, A.; Ammirati, E.; Morici, N. Heart Failure Management through Telehealth: Expanding Care and Connecting Hearts. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | EXCOR Active | Ikus |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Noise | 45 dB (A) in BVAD mode | 58 dB (A) in BVAD mode |

| Dimensions | 33 × 40 × 22 cm | 46 × 95 × 73 cm |

| Weight | 15 kg | 90 kg |

| Battery Runtime | ≥5 h | ≤30 min |

| Intended Environment | Hospital environmental use 1 | Stationary use only |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ünesen, N.; Balmer, C.; Schweiger, M. The Introduction of a New Mobile Driving Unit for a Ventricular Assist Device in a Pediatric Patient (EXCOR Active). J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd11120392

Ünesen N, Balmer C, Schweiger M. The Introduction of a New Mobile Driving Unit for a Ventricular Assist Device in a Pediatric Patient (EXCOR Active). Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2024; 11(12):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd11120392

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜnesen, Nuri, Christian Balmer, and Martin Schweiger. 2024. "The Introduction of a New Mobile Driving Unit for a Ventricular Assist Device in a Pediatric Patient (EXCOR Active)" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 11, no. 12: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd11120392

APA StyleÜnesen, N., Balmer, C., & Schweiger, M. (2024). The Introduction of a New Mobile Driving Unit for a Ventricular Assist Device in a Pediatric Patient (EXCOR Active). Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 11(12), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd11120392