Nurses’ Clinical Practice in Nursing Homes: Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk Assessment

Abstract

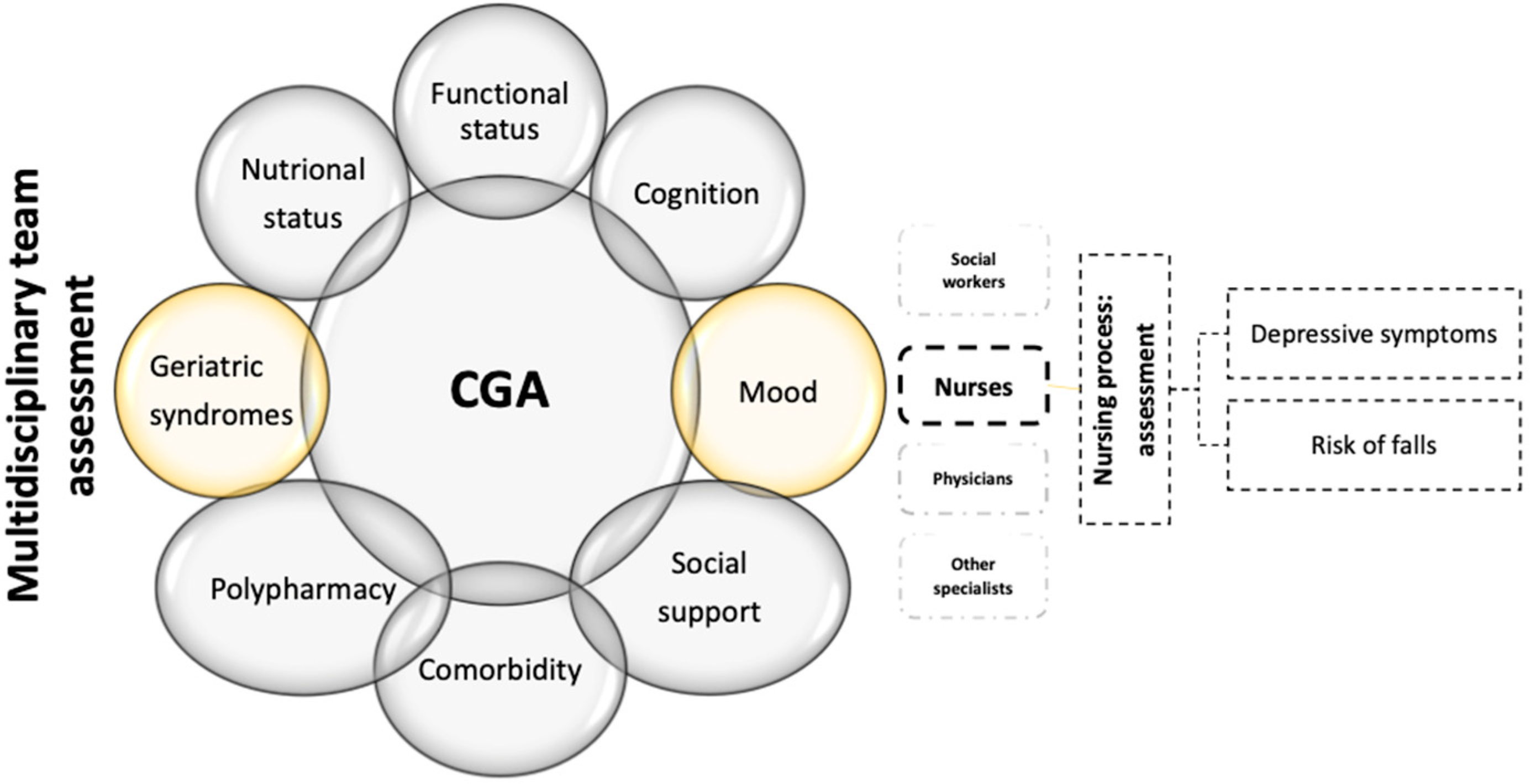

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Framework

2.3. Population, Setting and Sample

2.4. Survey Instrument

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Response Rates, NHs’ Principal Speciality and Cantonal Health Regions

3.2. Participants’ Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics

3.3. Clinical Practices for Assessing Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk

3.4. Using Validated Scales to Assess Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk

3.5. Associations Between Nurses’ Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics and Their Use of Validated Scales for Assessing Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk

3.6. Correlations Between Nurses’ Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics and Their Clinical Practices Using Validated Scales for Assessing Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk

3.7. Multivariate Logistic Regressions

3.8. Participants Perceptions of the Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Falls

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Practices for Assessing Depression and Fall Risk

4.2. Propositions for Clinical Practice

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OFS. Vieillissement Actif; Bundesamt für Statistik: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2018.

- Statistique Vaud. Perspectives Démographiques pour le Canton de Vaud; Statistique Vaud: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021.

- Seematter-Bagnoud, L.; Belloni, G.; Zufferey, J.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Büla, C.; Pellegrini, S. Espérance de Vie et État de Santé: Quelle Évolution Récente? Obsan Bulletin 03/2021; Observatoire Suisse de la Santé: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2021; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, S.; Dutoit, L.; Pahud, O.; Dorn, M. Bedarf an Alters- und Langzeitpflege in der Schweiz. Prognosen bis 2040; Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2022; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Kong, D.; Shelley, M. Making the Decision to Move to a Nursing Home: Longitudinal Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Schön, G.; Schäfer, I.; Glaeske, G.; Van Den Bussche, H.; Hansen, H. Multimorbidity and long-term care dependency—A five-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeser, M. Santé des Personnes Ágées Vivant en Établissement Médico-Social; Office Fédéral de la Statistique (OFS): Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2012.

- Gleeson, H.; Hafford-Letchfield, T.; Quaife, M.; Collins, D.A.; Flynn, A. Preventing and responding to depression, self-harm, and suicide in older people living in long term care settings: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damián, J.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Valderrama-Gama, E. Descriptive epidemiology of undetected depression in institutionalized older people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010, 11, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, C.A.; Wei, W.; Akincigil, A.; Lucas, J.A.; Bilder, S.; Crystal, S. Prevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in Ohio. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2007, 8, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadborn, N.H.; Goodman, C.; Zubair, M.; Sousa, L.; Gladman, J.R.F.; Dening, T.; Gordon, A.L. Role of comprehensive geriatric assessment in healthcare of older people in UK care homes: Realist review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.I.; Al-Harbi, A.B.; Al-Shihabi, A.M.; Al-Daour, D.S.; Sharif, R.S. Falls in the elderly: Assessment of prevalence and risk factors. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 16, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, A.; Matuz, M.; Csatordai, M.; Szalai, G.; Bálint, A.; Benkő, R.; Soós, G.; Doró, P. Medication use and risk of falls among nursing home residents: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Lu, S.F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, B.; Copeland, L.; Gurwitz, J.H. Body Mass Index, Falls, and Hip Fractures Among Nursing Home Residents. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Ruller, S.; Frank, C.; Bell, A.; Jacobson, M.; Pardo, J.P.; Ramsey, T.; Sobala, M.; Fung, C.; Kobewka, D. Incidence Morbidity and Mortality from Falls in Skilled Nursing Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 1690–1699.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, H.; Muazzam, S.; Nasrullah, M. Unintentional falls mortality among elderly in the United States: Time for action. Injury 2012, 43, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekna, V.; Stukas, R.; Tamulaityte-Morozoviene, I.; Surkiene, G.; Tamulaitiene, M. Self-reported consequences and healthcare costs of falls among elderly women. Medicina 2015, 51, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, S.; Brau, F.; Galluzzo, V.; Santagada, D.A.; Loreti, C.; Biscotti, L.; Laudisio, A.; Zuccalà, G.; Bernabei, R. Falls Among Older Adults: Screening, Identification, Rehabilitation, and Management. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaboni, A.; Flint, A.J. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: A clinical review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Shi, Y.; Xie, X.Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.A.; Zhang, J.E. Incidence and Risk Factors of Falls Among Older People in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirgiene, L.; Brent, L. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment from a Nursing Perspective. In Fragility Fracture Nursing: Holistic Care and Management of the Orthogeriatric Patient; Hertz, K., Santy-Tomlinson, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Smeeth, L.; Guttmann, A.; Harron, K.; Moher, D.; Petersen, I.; Sorensen, H.T.; von Elm, E.; Langan, S.M.; Committee, R.W. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, F.; Solfrizzi, V.; Lozupone, M.; Barulli, M.R.; D’Urso, F.; Stallone, R.; Dibello, V.; Noia, A.; Di Dio, C.; Daniele, A.; et al. An Old Challenge with New Promises: A Systematic Review on Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Long-Term Care Facilities. Rejuvenation Res. 2018, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Aprile, P.L.; Veronese, N.; Lacorte, E.; Morganti, W.; Custodero, C.; Piscopo, P.; Fabrizi, E.; Gatta, F.D.; Merlo, A.; et al. The Italian guideline on comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for the older persons: A collaborative work of 25 Italian Scientific Societies and the National Institute of Health. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewangizaw, Z. Determinants towards Implementation of Nursing Process. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 4, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merçay, C.; Grünig, A.; Dolder, P. Personnel de Santé en Suisse—Rapport National 2021. Effectifs, Besoins, Offre et Mesures pour Assurer la Relève; Observatoire Suisse de la Santé: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2021; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, T.E.; McCabe, M.P.; Mellor, D.; Karantzas, G.; George, K. Knowledge of late-life depression: An empirical investigation of aged care staff. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundberg, A.; Hansson, A.; Hilleras, P.; Religa, D. District nurses’ perspectives on detecting mental health problems and promoting mental health among community-dwelling seniors with multimorbidity. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, R.T.; Zuidema, S.U.; Leontjevas, R.; Gerritsen, D.L. Comprehensive assessment of depression and behavioral problems in long-term care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Geriatrics Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists. Collaborative Approaches to Treatement: Depression Among Older People Living in Care Homes; British Geriatrics Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taberna, M.; Gil Moncayo, F.; Jane-Salas, E.; Antonio, M.; Arribas, L.; Vilajosana, E.; Peralvez Torres, E.; Mesia, R. The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and Quality of Care. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Kakkadasam, V. Ability of nurses to identify depression in primary care, secondary care and nursing homes—A meta-analysis of routine clinical accuracy. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, H.; Cordingley, L.; Burns, A.; Mozley, C.G.; Sutcliffe, C.; Challis, D.; Huxley, P. Recognition of depression by staff in nursing and residential homes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2000, 9, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühl, K.G.; Luijendijk, H.J.; Muller, M.T. Nurses’ and nursing assistants’ recognition of depression in elderly who depend on long-term care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2007, 8, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, D.; Daly, F.; Martin, F.C.; McMurdo, M.E. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: A systematic review. Age Ageing 2004, 33, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Blazer, D.G. Depression in long-term care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smalbrugge, M.; Jongenelis, L.; Pot, A.M.; Beekman, A.T.; Eefsting, J.A. Screening for depression and assessing change in severity of depression. Is the Geriatric Depression Scale (30-, 15- and 8-item versions) useful for both purposes in nursing home patients? Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Cella, A.; Pilotto, A.; Daragjati, J.; Veronese, N.; Musacchio, C.; Mello, A.M.; Logroscino, G.; Padovani, A.; Prete, C.; et al. Three Decades of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Evidence Coming from Different Healthcare Settings and Specific Clinical Conditions. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 192.e1–192.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekes, W.M.; Korevaar, J.C.; Leemrijse, C.J.; van de Goor, I.A. Practical and validated tool to assess falls risk in the primary care setting: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, A.L.; Nitz, J.C.; Low Choy, N.L.; Haines, T. Measuring fall risk and predicting who will fall: Clinimetric properties of four fall risk assessment tools for residential aged care. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Falls: Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older People; NICE: Manchester, UK, 2013; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H. Tools for assessing fall risk in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innab, A.M. Nurses’ perceptions of fall risk factors and fall prevention strategies in acute care settings in Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvelde, T.; McVeigh, C.; Toson, B.; Greenaway, M.; Lord, S.R.; Delbaere, K.; Close, J.C. Depressive symptomatology as a risk factor for falls in older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambaro, E.; Gramaglia, C.; Azzolina, D.; Campani, D.; Molin, A.D.; Zeppegno, P. The complex associations between late life depression, fear of falling and risk of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 73, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, R.; Okubo, Y. Depression, Fear of Falling, Cognition and Falls; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Huitzi-Egilegor, J.X.; Elorza-Puyadena, M.I.; Urkia-Etxabe, J.M.; Asurabarrena-Iraola, C. Implementation of the nursing process in a health area: Models and assessment structures used. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2014, 22, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Valizadeh, L.; Tabrizi, F.J.; Behshid, M.; Lotfi, M. Challenges associated with the implementation of the nursing process: A systematic review. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.R.; Ishler, K.J. Family Involvement in the Nursing Home and Perceived Resident Quality of Life. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, S.; Halcomb, E.; Ashley, C.; Kean, A.; Moxham, L.; Patterson, C. An integrative review of primary health care nurses’ mental health knowledge gaps and learning needs. Collegian 2022, 29, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.J.; Hirdes, J.P. Evaluation of the Predictive Accuracy of the interRAI Falls Clinical Assessment Protocol, Scott Fall Risk Screen, and a Supplementary Falls Risk Assessment Tool Used in Residential Long-Term Care: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Can. J. Aging 2020, 39, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colón-Emeric, C.S.; Corazzini, K.; McConnell, E.; Pan, W.; Toles, M.; Hall, R.; Batchelor-Murphy, M.; Yap, T.L.; Anderson, A.L.; Burd, A.; et al. Study of Individualization and Bias in Nursing Home Fall Prevention Practices. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou, C.; Ozer, B.U.; Essau, C.A. Self-Report Questionnaires. In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women/men | 99 (85.3)/17 (17.7) | ||

| Age in years | 44.59 (11.3) | 25–65 | |

| <35 | 31 (26.7) | ||

| 35–44 | 28 (24.1) | ||

| 45–54 | 24 (20.7) | ||

| ≥55 | 33 (28.4) | ||

| Professional experience in years | 18.4 (10.5) | 1–43 | |

| Professional NH experience in years | 13.1 (9.2) | 1–40 | |

| Advanced training in geriatrics | |||

| Yes/No | 44 (37.9)/72 (62.1) | ||

| Advanced training in old age psychiatry | |||

| Yes/No | 51 (44.0)/65 (56.0) |

| Never n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Occasionally n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Frequently n (%) | Very Often n (%) | Always n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR 1–3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms assessment using a validated scale | 8 (6.9) | 26 (22.4) | 21 (18.1) | 17 (14.7) | 21 (18.1) | 14 (12.1) | 9 (7.8) | 3.82 (1.7) | 4 (3.0) |

| Falls risk assessment using a validated scale | 14 (12.1) | 25 (21.6) | 5 (4.3) | 18 (15.5) | 27 (23.3) | 15 (12.9) | 12 (10.3) | 3.97 (1.9) | 4 (3.0) |

| Depressive Symptoms Assessment Using a Validated Scale Rs (95%CI) | Fall Risk Assessment Using a Validated Scale Rs (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced training in geriatrics | 0.275 ** (0.092–0.440) | 0.185 * (−0.003–0.360) |

| Advanced training in old age psychiatry | 0.256 ** (0.072–0.423) | 0.171 (−0.018–0.347) |

| Variables | B a | Std. Error | Wald b | Df c | Sig. d | Exp(B) e | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||

| Constant | −0.913 | 1.895 | 0.232 | 1 | 0.630 | 0.401 | ||

| NHs specialising in geriatrics | 0.642 | 0.814 | 0.621 | 1 | 0.431 | 1.900 | 0.385 | 9.373 |

| NHs specialising in geriatrics and old age psychiatry | −0.080 | 0.636 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.900 | 0.923 | 0.265 | 3.213 |

| Professional experience in years | −0.057 | 0.043 | 1.730 | 1 | 0.188 | 0.945 | 0.868 | 1.028 |

| Professional NH experience in years | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 1 | 0.848 | 1.007 | 0.938 | 1.081 |

| Advanced training in geriatrics | 1.350 | 0.619 | 4.758 | 1 | 0.029 | 3.859 | 1.147 | 12.982 |

| Advanced training in old age psychiatry | 1.256 | 0.570 | 4.862 | 1 | 0.027 | 3.512 | 1.150 | 10.726 |

| Age in years | 0.059 | 0.044 | 1.843 | 1 | 0.175 | 1.061 | 0.947 | 1.155 |

| Sex | −0.253 | 0.738 | 0.120 | 1 | 0.729 | 0.777 | 0.187 | 3.234 |

| Variables | B a | Std. Error | Wald b | Df c | Sig. d | Exp(B) e | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||

| Constant | 2.144 | 1.730 | 1.535 | 1 | 0.215 | 8.533 | ||

| NHs specialising in geriatrics | 2.212 | 0.754 | 8.615 | 1 | 0.003 | 9.134 | 2.085 | 40.006 |

| NHs specialising in geriatrics and old age psychiatry | 1.087 | 0.573 | 3.592 | 1 | 0.058 | 2.964 | 0.964 | 9.121 |

| Professional experience in years | 0.017 | 0.034 | 0.265 | 1 | 0.607 | 1.017 | 0.953 | 1.086 |

| Professional NH experience in years | −0.042 | 0.031 | 1.792 | 1 | 0.181 | 0.959 | 0.902 | 1.020 |

| Advanced training in geriatrics | 0.828 | 0.474 | 3.052 | 1 | 0.081 | 2.288 | 0.904 | 5.788 |

| Advanced training in old age psychiatry | 1.122 | 0.474 | 5.596 | 1 | 0.018 | 3.071 | 1.212 | 7.782 |

| Age in years | −0.001 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.976 | 0.999 | 0.938 | 1.064 |

| Sex | −1.736 | 0.755 | 5.281 | 1 | 0.022 | 0.176 | 0.040 | 0.775 |

| I Totally Disagree, n (%) | I Do Not Agree, n (%) | I Tend to Disagree, n (%) | I Neither Agree or Disagree, n (%) | I Tend to Agree, n (%) | I Agree, n (%) | I Totally Agree, n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR 1–3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults with symptoms of depression are at a greater risk of falls. | 3 (2.6) | 13 (11.2) | 15 (12.9) | 19 (16.4) | 43 (37.1) | 11 (9.5) | 12 (10.3) | 4.44 (1.5) | 5 (2.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Queirós, A.M.; von Gunten, A.; Martins, M.M.; Verloo, H. Nurses’ Clinical Practice in Nursing Homes: Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk Assessment. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9060158

Queirós AM, von Gunten A, Martins MM, Verloo H. Nurses’ Clinical Practice in Nursing Homes: Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk Assessment. Geriatrics. 2024; 9(6):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9060158

Chicago/Turabian StyleQueirós, Alcina Matos, Armin von Gunten, Maria Manuela Martins, and Henk Verloo. 2024. "Nurses’ Clinical Practice in Nursing Homes: Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk Assessment" Geriatrics 9, no. 6: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9060158

APA StyleQueirós, A. M., von Gunten, A., Martins, M. M., & Verloo, H. (2024). Nurses’ Clinical Practice in Nursing Homes: Depressive Symptoms and Fall Risk Assessment. Geriatrics, 9(6), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9060158