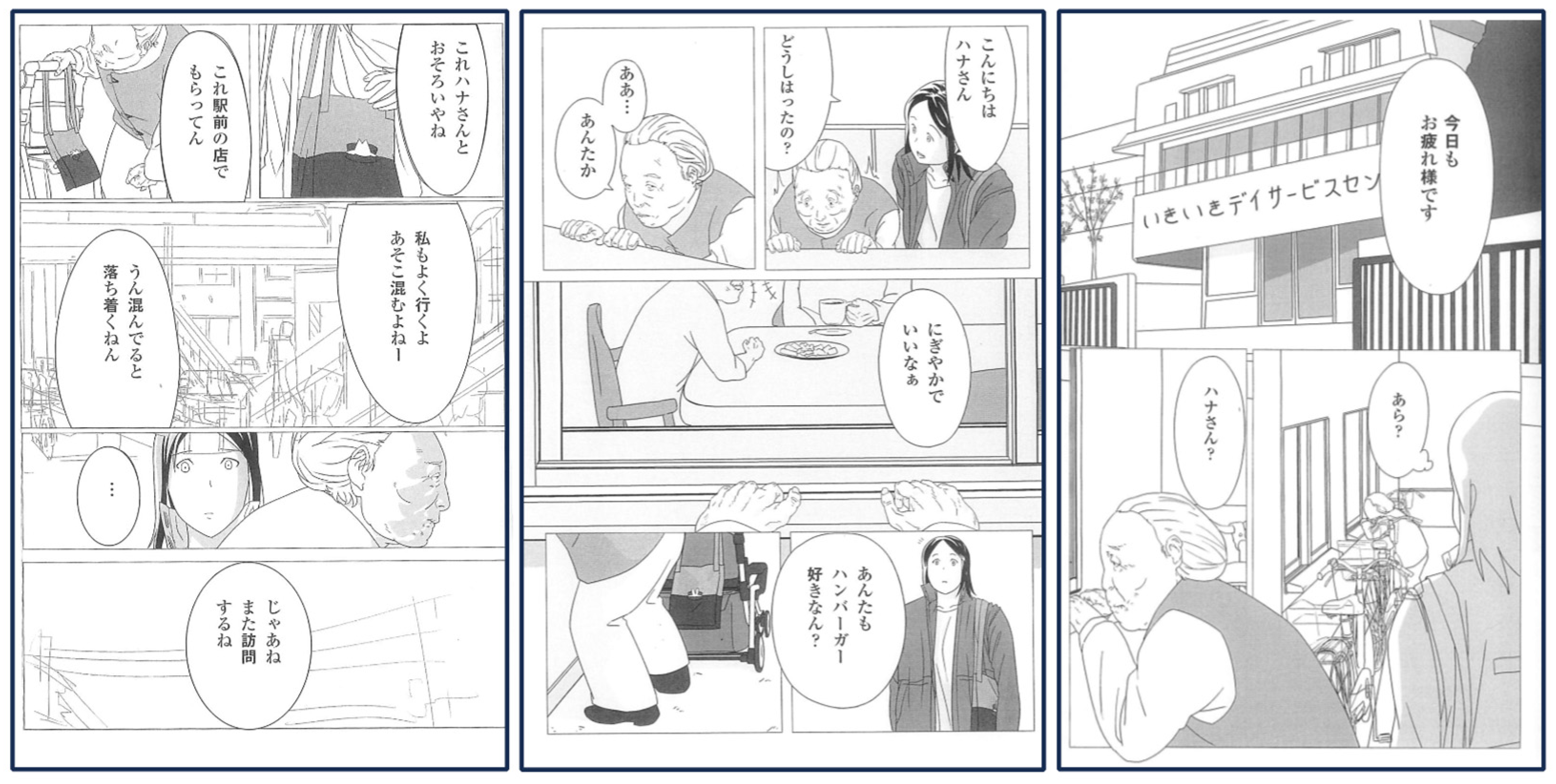

Mutually Supportive and Inclusive Societies Driven by Community Social Workers in Japan: A Thematic Analysis of Japanese Comics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting: Toyonaka City

2.2. Community Social Workers

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

Reflexivity

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Thematic Analysis Results

3.2. Core Value of Respect for Professionalism and Dedication to Vulnerable People

“We must understand the current social systems that create poverty. There are three types of child poverty. The first is economic poverty, which arises from income-related challenges… The second is relational poverty. While economic poverty can be somewhat addressed with available support when sought, as living conditions become tougher, connections weaken… The third type is cultural poverty, which arises when individuals only understand their own teachings and therefore don’t cook… This can contribute to a cycle of poverty. This is why community dining spaces for children hold great significance, as they aim to expand child-rearing practices and familial relationships”.(Comic 5)

“CSWs are frequently present in local areas, providing them many opportunities to identify daily issues faced by residents. They often initiate support based on matters they find concerning. Although CSWs must independently address some issues, it’s even more beneficial for community members to identify problems and collaborate on solutions. Such a collaborative approach strengthens the community’s capabilities and resilience, and CSWs therefore, immediately respond to community inquiries. Moreover, even when offering support amid bureaucratic challenges, a determined and unwavering attitude is required”.(Comic 1)

“For those who have long been obstructed by many and who have persisted, building a relationship of trust is no trivial matter. Thorough respect for an individual is required. It’s crucial to value the individual’s feelings and construct support based on their self-determination. However, in many cases, support is built on a provider-centric premise, prioritizing services. A deep respect for individuals will, in turn, quickly create relationships with them”.(Comic 2)

3.3. Personalized Support Oriented toward Person-Centered Suffering

“The challenges faced by those facing financial hardships are among the most difficult for individuals to signal for help. Given the prevailing notion of personal responsibility, seeking consultation at City Hall can be a significant hurdle. In other words, seeking help can make one feel humiliated; so offering support with an understanding of this sentiment is essential. I often encounter individuals who become despondent and are on the verge of giving up on their lives. However, even if the person says that they are fine, as supporters, we must not give up on those close to giving up on life. Financial hardship can happen to anyone, and society needs to adopt a perspective that aims to rebuild lives, starting with welfare support”.(Comic 4)

“Even if someone happens to be homeless when we meet them, by reflecting on the various stories that have shaped their life up to that point, we can help draw out their strengths. Making curry rice reminded her of her life journey, and the look on her face when she feels needed by others hints at times when she truly shined”.(Comic 2)

“It’s easy to say, ‘connect them to administrative services’, but for those with complex pasts, there’s a significant fear of their histories being probed into when utilizing these services. Therefore, taking an active role and moving with individuals on their journey through what we call the ‘co-traveling’ support method is effective. Instead of judging whether individuals can use a service, it is essential to support them with the understanding that they are the primary stakeholders in their own lives”.(Comic 3)

3.4. Promoting Inclusive Community Engagement

“Communities inherently have both exclusive and inclusive characteristics. Particularly in local areas, the stance of community leaders—whether they adopt an exclusionary or inclusive perspective—significantly affects the lives of those facing challenges and requiring social support. By integrating a methodology through which community leaders learn through individual challenges, creating an inclusive environment ensures a stable living foundation and plays a crucial role in subsequent support scenarios. Believing in the power of community and adopting a collaborative, supportive stance can truly transform the community”.(Comic 2)

“Often, individuals perceived as ‘troublesome’ in a community are actually grappling with underlying challenges. Behaviors exhibited by those with hoarding disorders, dementia, or other anxieties often appear problematic to neighbors. Community members can gain insight into their circumstances by focusing on the root issues faced by these individuals. This fosters a perspective of inclusion rather than exclusion. Specifically, it is crucial to contemplate how to continually support these individuals in the communities they know, with CSWs playing a pivotal role in accompanying and assisting them in their journey”.(Comic 6)

“It is precisely because one is cherished that they can evolve into someone who supports others. Indeed, aligned with the theme of community coexistence, those who feel valued by society can learn, regain confidence, and develop profound respect for every individual who wishes to support others. Such transformations require time and space. As families have become smaller and influence from individuals outside immediate family members diminishes, now more than ever, community dining spaces for children serve as crucial junctions connecting the community, schools, and homes”.(Comic 5)

3.5. Connecting and Reorganizing Communities to Promote Inclusive Societies

“We must address the very structural issues in society that make it difficult for those without familial support to live comfortably. Recognizing that individuals often share challenges, it’s imperative to understand and communicate these issues to local governments and communities. What’s called for is a proactive approach to resolving these challenges”.(Comic 2)

“I believe that it is essential for every individual in a community to provide both support and be supported. Regardless of whether it’s individuals with dementia sharing stories from the past, ingenious solutions during mask shortages amid the COVID-19 pandemic, war veterans in wheelchairs sharing their wartime experiences, or older adults contributing their professional experiences to local volunteer activities, older adults have more to offer than merely being care recipients. Their vast wisdom and experience should be harnessed for societal benefit. While receiving caregiving support, their personal experiences can greatly contribute to the community”.(Comic 6)

“The perspective on promptly identifying and approaching individuals who cannot send out SOS signals is critical. Many within the population experiencing genuine distress cannot voice their struggles. Additionally, with the transition from welfare service placement to contracts, there’s a need for community-building to identify individuals who refuse contracts or are unable to send SOS signals. Beyond building supportive structures such as local and oral welfare committees, future efforts must also focus on reaching out to individuals in apartments or those who do not participate in neighborhood associations. Strategies such as monitoring systems targeting those outside neighborhood associations and ‘rolling operations’ are essential. Collaborative networks involving electricity, gas, water utilities, pioneering businesses, newspapers, delivery services, and various other sectors play a vital role in ensuring that no individual is left unattended. Diverse methods are required to ensure that no one falls through the cracks”.(Comic 6)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freedman, A.; Nicolle, J. Social isolation and loneliness: The new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Can. Fam. Physician 2020, 66, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, T.K.M.; Prichett, L.; Szanton, S.L.; Roberts Lavigne, L.C.; Thorpe, R.J. Social isolation, homebound status, and race among older adults: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (2011–2019). J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, A.A.; Leggett, D.; Vollmer, D.; Perez, V.; Smith, R.; Goodman, E.; Mayes, C.; McLellan, C.; Laird, N.; Beck, A.F.; et al. Cultivating social relationships and disrupting social isolation in low-income, high-disparity neighbourhoods in Ohio, USA. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 1876–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Geldenhuys, G.; Gott, M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S.L.; Bedrov, A. Social isolation and social support in good times and bad times. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Maiguma, K.; Yata, A.; Sano, C. Rebuilding social capital through osekkai conferences in rural communities: A social network analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Solving social problems in aging rural Japanese communities: The development and sustainability of the Osekkai conference as a social prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Kita, T. Social prescription for isolated parenting in Japan: Socioeconomic characteristics of mothers with weak social connectivity in their community. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1815–e1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Sugawara, I.; Fukaya, T.; Okamoto, S.; Liang, J. Retirement and social activities in Japan: Does age moderate the association? Res. Aging 2022, 44, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.C. Community social work in a rural state. Health Soc. Work 1980, 5, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. The role of the social worker. Nephrol. News Issues 2014, 28, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Berrett-Abebe, J.; Donelan, K.; Berkman, B.; Auerbach, D.; Maramaldi, P. Physician and nurse practitioner perceptions of social worker and community health worker roles in primary care practices caring for frail elders: Insights for social work. Soc. Work Health Care 2020, 59, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, D.R. Ontology, epistemology, methodology, and methods: Information for librarian researchers. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Ashcroft, R. Social work leadership competencies for practice amid crisis: A scoping review. Health Soc. Work 2022, 47, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederbaum, J.A.; Ross, A.M.; Ruth, B.J.; Keefe, R.H. Public health social work as a unifying framework for social work’s grand challenges. Soc. Work 2019, 64, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Novel insights into patients’ life-worlds: The value of qualitative research. Lan. Psyc. 2019, 6, 720–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, G.F.; Sykes, P. Steps toward engagement integrity: Learning from participatory visual methods in marginalized South African communities. Front. Pub. Health 2022, 10, 794905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bochatay, N.; Relyea-Chew, A.; Buttrick, E.; Amdahl, C.; Kim, L.; Frans, E.; Mossanen, M.; Khandekar, A.; Fehr, R.; et al. Individual, interpersonal, and organisational factors of healthcare conflict: A scoping review. J. Interprof. Care 2017, 31, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, P. “It’s just the abuse that needs to stop”: Professional framing of sibling relationships in a grounded theory study of social worker decision making following sibling sexual behavior. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2020, 29, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinland, A.; Loubière, S.; Boucekine, M.; Boyer, L.; Fond, G.; Girard, V.; Auquier, P. Effectiveness of a housing support team intervention with a recovery-oriented approach on hospital and emergency department use by homeless people with severe mental illness: A randomised controlled trial. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillian, J.P. Community health workers and primary health care in Honduras. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 1993, 5, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulman, J.; Savage, D.; Vrooman, P.; McGillivray, M. Social group work: Building a professional collective of hospital social workers. Soc. Work Health Care 2004, 39, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, E.; Biondo, E.; Mosso, C.O. The role of social worker in promoting immigrants’ integration. Soc. Work Public Health 2018, 33, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M.I.L.; Graham, J.R. Building competence in practice with the polyamorous community: A scoping review. Soc. Work 2020, 65, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, M.; Ricci, E.; Huber, G.; Myers, M. Opportunities for social workers in the patient centered medical home. Soc. Work Public Health 2015, 30, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Cheung, M.; Leung, P.; He, X. Voices from social work graduates in China: Reasons for not choosing social work as a career. Soc. Work 2016, 61, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthorpe, J. The dement in the community: Social work practice with people with dementia revisited. Dementia 2016, 15, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, C.; Hynes, M.; Deslauriers, A.; Kitcher, L.L.; MacMillan, T.; Paradis, D.; Curry, S. Helping families thrive: Co-designing a program to support parents of children with medical complexity. Healthc. Q. 2021, 24, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F. Identifying, preventing, and addressing job burnout and vicarious burnout for social work professionals. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work 2016, 13, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, L.S.; Marton, K.I.; Barbaccia, J.C.; Randolph, J. Physician, nurse, and social worker collaboration in primary care for chronically ill seniors. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridley, K.; Brooks, J.; Glendinning, C. Good practice in social care for disabled adults and older people with severe and complex needs: Evidence from a scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chui, C.H.; Chan, O.F.; Tang, J.Y.M.; Lum, T.Y.S. Fostering civic awareness and participation among older adults in Hong Kong: An empowerment-based participatory photo-voice training model. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forenza, B.; Eckert, C. Social worker identity: A profession in context. Soc. Work 2018, 63, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anleu-Hernández, C.M.; García-Moreno, C.; Zafra-Aparici, E.; Forns-Fernández, M.V. Strengths of Latinas in Spain: A challenge for a resilient social work practice. Soc. Work 2021, 66, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, J.L.; Anantharaman, M. Informal work and sustainable cities: From formalization to reparation. One Earth 2020, 3, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Tier, M.; Potting, M.; Hermans, K. Stimulating the problem-solving abilities of users in an online environment. A study of a Dutch online social casework intervention. Health Soc. Care Comm. 2018, 26, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennerstrom, A.; Haywood, C.G.; Smith, D.O.; Jindal, D.; Rush, C.; Wilkinson, G.W. Community health worker team integration in Medicaid managed care: Insights from a national study. Front. Pub. Health 2022, 10, 1042750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, A.; Parrish, D.E. Comparing social worker and non-social worker outcomes: A research review. Soc. Work 2012, 57, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Core value of respect for professionalism and dedication to vulnerable people | Improving their understanding of social systems is key for CSWs. They continually enhance their comprehension of social systems to address inclusivity and social issues. When approaching a community, it is vital that they are available and responsive to any consultation without evasion. They maintain an unwavering trust of others, believing those they engage with will inevitably change over time. When initiating a dialogue, they are mindful of recognizing layers within the conversation, building relationships by leveraging others’ interests and gradually transitioning to the issues they seek to resolve. CSWs place great emphasis on becoming the voice for the disadvantaged. When these individuals cannot express themselves, CSWs advocate for them, ensuring they can easily access social security. They always attempt to open up the hearts of those in distress and consistently approach them openly, which allows them to connect deeply and continue their support. CSWs feel both moved and fulfilled by positive changes for disadvantaged groups, which motivates them to persevere in their work. |

| Personalized support oriented toward person-centered suffering | CSWs prioritize being immediately supportive in response to residents’ concerns and are swift in addressing their consultations. They are interested in individual problems and cherish their connection with others, considering others’ feelings and advocating for them. Through dialogue with various related agencies, CSWs transform individual issues into collective concerns. They demonstrate an accepting attitude, understand layers of conversation, advance dialogue, candidly express their feelings, and patiently approach any reaction from the other side. By providing tailored assistance to each individual’s challenges, CSWs consistently embody a collaborative support approach. They continuously contemplate the support methods best suited for each person in need. They are mindful of recipients during problem resolution, recognizing that each person requiring support has a unique background; CSWs consistently practice this consideration throughout their assistance efforts. They are conscious of establishing a support system centered on the disadvantaged. |

| Promoting inclusive community engagement | CSWs are conscious of involving community residents in the support process, actively engaging in dialogue with them throughout the problem-solving process. They work to inspire motivation without damaging the community’s circumstances and urge them to participate in actual activities. When observing instances of exclusionary attitudes among residents, they make efforts to promote inclusivity. They aim for enhanced inclusivity through problem solving, realizing that by addressing one issue, they can improve overall community inclusivity. Recognizing the importance of sharing inclusivity growth within the community, CSWs deepen residents’ understanding of their community by sharing case studies. Through actual activities, they help those receiving support to transition from being supported to being supporters themselves via interactions with CSWs and community members. CSWs also push forward initiatives to create new roles for residents, continuously suggesting methods for individualized social participation tailored to their life stages, ensuring diverse societal involvement. |

| Connecting and reorganizing communities to promote inclusive societies | CSWs recognize the importance of connecting individual problems to broader societal issues, taking a single local issue and magnifying it to a community-level concern, thereby structuring solutions. From individual resolutions to systematizing solutions, CSWs support establishing new relationships to create a new foundation for the lives of the disadvantaged. Within this process, CSWs expand their knowledge of modern societal issues, reconstituting social resources to help residents understand that the problems they perceive are not unique but rather challenges the community should address. By linking unresolved societal problems to community empowerment, CSWs work to increase inclusivity on a community-wide scale, striving to establish a system that can embrace diverse individuals. By supporting the establishment of new relationships for the disadvantaged throughout the community, CSWs promote community growth, including its capacity for inclusivity, via solving social issues. In their quest to find solutions to unresolved societal challenges, CSWs connect various related agencies, organically linking and reconstituting diverse social resources and continuing to advocate for enhanced community capacity through seamless support for the disadvantaged. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohta, R.; Naito, Y.; Sano, C. Mutually Supportive and Inclusive Societies Driven by Community Social Workers in Japan: A Thematic Analysis of Japanese Comics. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8060113

Ohta R, Naito Y, Sano C. Mutually Supportive and Inclusive Societies Driven by Community Social Workers in Japan: A Thematic Analysis of Japanese Comics. Geriatrics. 2023; 8(6):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8060113

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhta, Ryuichi, Yumi Naito, and Chiaki Sano. 2023. "Mutually Supportive and Inclusive Societies Driven by Community Social Workers in Japan: A Thematic Analysis of Japanese Comics" Geriatrics 8, no. 6: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8060113

APA StyleOhta, R., Naito, Y., & Sano, C. (2023). Mutually Supportive and Inclusive Societies Driven by Community Social Workers in Japan: A Thematic Analysis of Japanese Comics. Geriatrics, 8(6), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8060113