Vietnamese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (30 Items): Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

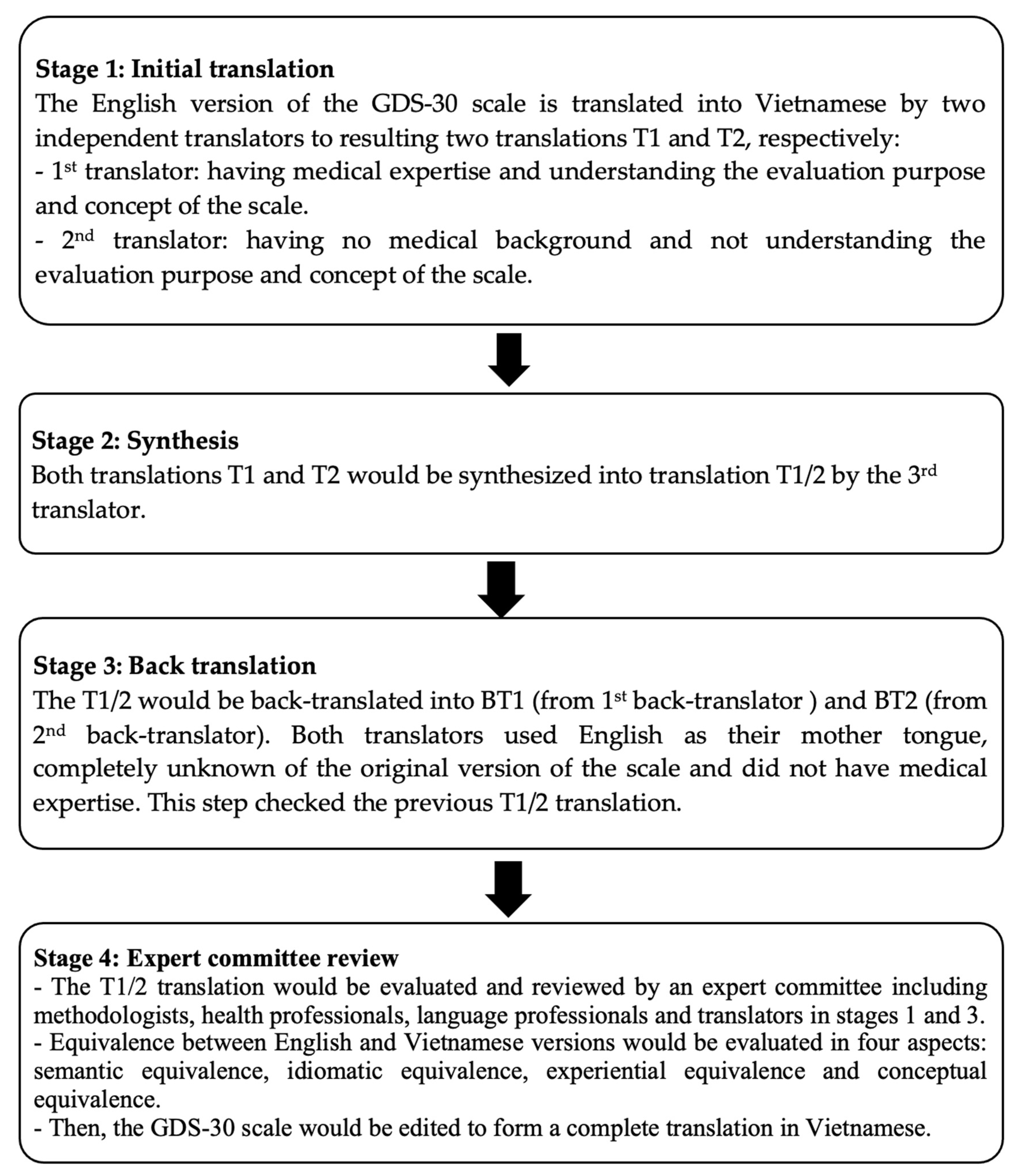

2.1. Translation of the GDS-30 Scale

2.2. Validation of the GDS-30 Scale

2.2.1. Study Design

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Sample Size

2.2.4. Validation Criteria

Reliability

2.2.5. Validity

2.2.6. Data Analysis

2.2.7. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Test

3.1.1. Consistency

3.1.2. Stability

3.2. Validity

3.2.1. Content Validity

3.2.2. Construct Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons; Population Division, United Nations: Fertility, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Completed Results of the 2019 Viet Nam Population and Housing Census; Statistical Publishing House: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2019.

- Vietnam National Committee on Aging. Towards a Comprehensive National Policy for An Ageing in Viet Nam; Vietnam National Committee on Aging: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2017-Highlights; Population Division, United Nations: Fertility, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.T.M.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, L.T.K. Factors Associated with Depression among the Elderly Living in Urban Vietnam. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2370284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borza, T.; Engedal, K.; Bergh, S.; Selbæk, G. Older people with depression-a three-year follow-up. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen 2019, 139, 01–10. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Yang, S.; Jia, W.; Wang, S.; Song, Y.; Cao, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; He, Y. Health-Related Quality of Life and Its Correlation With Depression Among Chinese Centenarians. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 580757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frénisy, M.C.; Plassard, C. Suicide in the elderly. Soins 2017, 62, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincigil, A.; Matthews, B.E. National Rates and Patterns of Depression Screening in Primary Care: Results From 2012 and 2013. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozela, M.; Bobak, M.; Besala, A.; Micek, A.; Kubinova, R.; Malyutina, S.; Denisova, D.; Richards, M.; Pikhart, H.; Peasey, A.; et al. The association of depressive symptoms with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Central and Eastern Europe: Prospective results of the HAPIEE study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 2047–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashok, V.G.; Ghosh, S.S. Prevalence of Depression among Hypertensive Patients Attending a Rural Health Centre in Kanyakumari. Natl. J. Community Med. 2019, 10, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, L.; Fau-Chen, Y.; Chen, P.; Fau-Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Fau-Hu, P.; Hu, Y. Prevalence of Depression in Patients With Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2015, 94, e1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.J.; Won, M.H. Depression and medication adherence among older Korean patients with hypertension: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Int. J. Nurs. Pr. 2017, 23, e12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, M.; Dube, S.; Johnston, J.M.; Pandav, R.; Chandra, V.; Dodge, H.H. Depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment and functional impairment in a rural elderly population in India: A Hindi version of the geriatric depression scale (GDS-H). Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.N.; Cho, M. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ty, W.E.; Davis, R.D.; Melgar, M.I.; Ramos, M. A Validation Study on the Filipino Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) using Rasch Analysis. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, N.D.; Quyen, B.T.; Tien, T.Q. Validation of a Brief CES-D Scale for Measuring Depression and Its Associated Predictors among Adolescents in Chi Linh, Hai Duong, Vietnam. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Bass, J.K.; German, D.; Nguyen, N.T.; Knowlton, A.R. A tool for sexual minority mental health research: The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a depressive symptom severity measure for sexual minority women in Viet Nam. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2016, 20, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tran, T.D.; Tran, T.; Fisher, J. Validation of three psychometric instruments for screening for perinatal common mental disorders in men in the north of Vietnam. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beaton, D.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH Outcome Measures Contributors to this Document. Inst. Work. Health 2007, 1, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam National Heart Association Vietnam. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults; National Heart Association: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DeVon, H.A.; Block, M.E.; Moyle-Wright, P.; Ernst, D.M.; Hayden, S.J.; Lazzara, D.J.; Savoy, S.M.; Kostas-Polston, E. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2007, 39, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.F.; Terkawi, A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11, S80–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Uttar Pradesh, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, M.; Fors, M.; Mullo, S.; González, P.; Viada, C. Internal Consistency of Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS 15-Item Version) in Ecuadorian Older Adults. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2020, 57, 0046958020971184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, F.V.; Split, M.; Filoteo, J.V.; Litvan, I.; Moore, R.C.; Pirogovsky-Turk, E.; Liu, L.; Lessig, S.; Schiehser, D.M. Does the Geriatric Depression Scale measure depression in Parkinson’s disease? Int J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, L.; Corbin, A.L.; Goveas, J.S. Depression and frailty in later life: A systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AThomas, M.; Cherian, V.; Antony, A. Translation, validation and cross-cultural adaptation of the geriatric depression scale (GDS-30) for utilization amongst speakers of Malayalam; the regional language of the South Indian State of Kerala. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, B.; Soysal, P.; Ellidokuz, H.; Isik, A.T. Validity and reliability of geriatric depression scale-15 (short form) in Turkish older adults. North. Clin. Istanb. 2018, 5, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudisio, A.; Incalzi, R.A.; Gemma, A.; Marzetti, E.; Pozzi, G.; Padua, L.; Bernabei, R.; Zuccalà, G. Definition of a Geriatric Depression Scale cutoff based upon quality of life: A population-based study. Int J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, e58–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongenelis, K.; Pot, A.M.; Eisses, A.M.H.; Gerritsen, D.L.; Derksen, M.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Kluiter, H.; Ribbe, M.W. Diagnostic accuracy of the original 30-item and shortened versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale in nursing home patients. Int J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, T.; Eker, E. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the geriatric depression scale in Turkish elderly: Are there different factor structures for different cultures? Int. Psychogeriatr. 2000, 12, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeoto, G.; Sansoni, J.; Scuccimarri, M.; Bruni, V.; De Santis, R.; Colucci, M.; Valente, D.; Tofani, M. A Psychometric Properties Evaluation of the Italian Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Depress. Res. Treat. 2018, 2018, 1797536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.J.; Huh, Y.; Lee, S.B.; Han, S.K.; Choi, S.W.; Lee, N.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Woo, J.I. Standardization of the korean version of the geriatric depression scale: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Psychiatry Investig. 2008, 5, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A.; Brooks, J.O.; Friedman, L.; Gratzinger, P.; Hill, R.D.; Zadeik, A.; Crook, T. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1991, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | The Original English Version | Vietnamese Version |

|---|---|---|

| 1 * | Are you basically satisfied with your life? | Về cơ bản Ông/Bà hài lòng với cuộc sống của mình? |

| 2 | Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? | Ông/Bà đã từ bỏ nhiều hoạt động và thú vui? |

| 3 | Do you feel that your life is empty? | Ông/Bà cảm thấy cuộc sống của mình thật trống rỗng? |

| 4 | Do you often get bored? | Ông/Bà thường cảm thấy buồn chán? |

| 5 * | Are you hopeful about your future? | Ông/Bà thấy hy vọng vào tương lai của mình? |

| 6 | Are you bothered by thoughts you can’t get out of your head? | Ông/Bà có phiền muộn bởi những suy nghĩ trong đầu không thể bỏ được? |

| 7 * | Are you good in spirits most of the time? | Tinh thần của ông bà tốt trong hầu hết thời gian? |

| 8 | Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? | Ông/Bà có sợ điều gì đó không hay sắp xảy đến với mình? |

| 9 * | Do you feel happy most of the time? | Hầu hết thời gian Ông/Bà cảm thấy hạnh phúc? |

| 10 | Do you often feel helpless? | Ông/Bà thường cảm thấy bất lực? |

| 11 | Do you often get restless and fidgety? | Ông/Bà thường cảm thấy bồn chồn, đứng ngồi không yên? |

| 12 | Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things? | Ông/Bà thích ở nhà hơn ra ngoài và làm những điều mới mẻ? |

| 13 | Do you frequently worry about your future? | Ông/Bà thường xuyên lo lắng về tương lai? |

| 14 | Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most? | Ông/Bà cảm thấy mình có nhiều vấn đề về trí nhớ hơn hết? |

| 15 * | Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? | Ông/Bà nghĩ hiện tại được sống là tuyệt vời? |

| 16 | Do you often feel downhearted and blue? | Ông/Bà thường cảm thấy buồn và nản chí? |

| 17 | Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? | Theo tình trạng hiện giờ, Ông/Bà cảm thấy khá vô ích? |

| 18 | Do you worry a lot about the past? | Ông/Bà lo lắng nhiều về quá khứ? |

| 19 * | Do you find life very exciting? | Ông/Bà nhận thấy cuộc sống rất hào hứng? |

| 20 | Is it hard for you to get started on new projects? | Ông/Bà thấy khó khăn để bắt đầu những dự định mới? |

| 21 * | Do you feel full of energy? | Ông/Bà cảm thấy tràn đầy năng lượng? |

| 22 | Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? | Ông/Bà cảm thấy tình trạng của mình là không có hy vọng? |

| 23 | Do you think that most people are better off than you are? | Ông/Bà nghĩ hầu hết mọi người đều sung sướng hơn mình? |

| 24 | Do you frequently get upset over little things? | Ông/Bà thường thấy bực bội với những việc nhỏ nhặt? |

| 25 | Do you frequently feel like crying? | Ông/Bà thường cảm thấy muốn khóc? |

| 26 | Do you have trouble concentrating? | Ông/Bà có khó tập trung? |

| 27 * | Do you enjoy getting up in the morning? | Ông /Bà có hào hứng thức dậy vào buổi sáng? |

| 28 | Do you prefer to avoid social gatherings? | Ông/Bà muốn tránh các tụ họp đông người? |

| 29 * | Is it easy for you to make decisions? | Có dễ dàng để Ông/Bà đưa ra các quyết định? |

| 30 * | Is your mind as clear as it used to be? | Ông/Bà vẫn minh mẫn như trước kia? |

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 75.24 ± 8.46 | |

| Age group | 60–69 years old | 93 | 28.2 |

| 70–79 years old | 126 | 38.2 | |

| ≥ 80 years old | 111 | 33.6 | |

| Gender | Female | 101 | 30.6 |

| Males | 229 | 69.4 | |

| Employment | Trade | 13 | 3.9 |

| Farmer | 41 | 12.4 | |

| Housewife | 21 | 6.4 | |

| Stop working | 252 | 76.4 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.9 | |

| Level of education | ≤ Primary | 248 | 75.2 |

| Secondary school | 50 | 15.2 | |

| High school | 18 | 5.5 | |

| > High school | 14 | 4.2 | |

| Marital status | Married | 210 | 63.6 |

| Single | 6 | 1.8 | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 114 | 34.5 | |

| Economic status | Poor | 27 | 8.2 |

| No poor | 303 | 91.8 | |

| Sleep disturbance | Yes | 273 | 82.7 |

| No | 57 | 17.3 | |

| Item | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If the Item Was Deleted | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.601 | 0.925 | 0.928 |

| 2 | 0.502 | 0.926 | |

| 3 | 0.585 | 0.925 | |

| 4 | 0.722 | 0.923 | |

| 5 | 0.480 | 0.926 | |

| 6 | 0.512 | 0.926 | |

| 7 | 0.645 | 0.924 | |

| 8 | 0.503 | 0.926 | |

| 9 | 0.641 | 0.924 | |

| 10 | 0.641 | 0.924 | |

| 11 | 0.555 | 0.925 | |

| 12 | 0.319 | 0.929 | |

| 13 | 0.558 | 0.925 | |

| 14 | 0.336 | 0.928 | |

| 15 | 0.526 | 0.926 | |

| 16 | 0.713 | 0.923 | |

| 17 | 0.536 | 0.925 | |

| 18 | 0.350 | 0.928 | |

| 19 | 0.636 | 0.924 | |

| 20 | 0.579 | 0.925 | |

| 21 | 0.592 | 0.925 | |

| 22 | 0.415 | 0.927 | |

| 23 | 0.474 | 0.926 | |

| 24 | 0.466 | 0.926 | |

| 25 | 0.519 | 0.926 | |

| 26 | 0.501 | 0.926 | |

| 27 | 0.528 | 0.926 | |

| 28 | 0.556 | 0.925 | |

| 29 | 0.569 | 0.925 | |

| 30 | 0.317 | 0.928 |

| Item | Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.152 | 0.268 |

| 2 | 0.386 | 0.004 |

| 3 | 0.126 | 0.359 |

| 4 | 0.439 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 0.297 | 0.028 |

| 6 | 0.458 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 0.429 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 0.421 | 0.001 |

| 9 | 0.443 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 0.452 | 0.001 |

| 11 | 0.331 | 0.014 |

| 12 | 0.603 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.346 | 0.01 |

| 15 | −0.098 | 0.477 |

| 16 | 0.363 | 0.007 |

| 17 | 0.270 | 0.046 |

| 18 | 0.444 | 0.001 |

| 19 | 0.102 | 0.458 |

| 20 | 0.336 | 0.012 |

| 21 | 0.495 | <0.001 |

| 22 | 0.313 | 0.02 |

| 23 | 0.179 | 0.191 |

| 24 | 0.373 | 0.005 |

| 25 | 0.530 | <0.001 |

| 26 | 0.149 | 0.279 |

| 27 | 0.39 | 0.003 |

| 28 | 0.288 | 0.033 |

| 29 | 0.535 | <0.001 |

| 30 | 0.542 | <0.001 |

| Total | 0.479 | <0.001 |

| Item | Semantic Equivalence | Idiomatic Equivalence | Experience Equivalence | Conceptual Equivalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale title | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 1 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 2 | 6/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 3 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 |

| 4 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 5 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| 6 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 5/7 | 6/7 |

| 7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 |

| 8 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| 9 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 10 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| 11 | 4/7 | 4/7 | 4/7 | 4/7 |

| 12 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 13 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 14 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 4/7 | 5/7 |

| 15 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 |

| 16 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 |

| 17 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 4/7 | 5/7 |

| 18 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 19 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| 20 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 21 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 22 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 23 | 4/7 | 4/7 | 4/7 | 4/7 |

| 24 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 25 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 26 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| 27 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| 28 | 5/7 | 5/7 | 4/7 | 5/7 |

| 29 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 |

| 30 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 |

| Average score | 184/210 (0.88) | 185/210 (0.88) | 177/210 (0.84) | 185/210 (0.88) |

| Characteristics | Depression | Non-Depression | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age group | 60–69 years | 30 | 32.3 | 63 | 67.7 | 0.102 |

| 70–79 years | 57 | 45.2 | 69 | 54.8 | ||

| ≥ 80 years | 50 | 45.0 | 61 | 55.0 | ||

| Gender | Female | 112 | 48.9 | 117 | 51.1 | <0.001 |

| Male | 25 | 24.8 | 76 | 75.2 | ||

| Employment | No | 115 | 45.6 | 137 | 54.4 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 22 | 28.2 | 56 | 71.8 | ||

| Level of education | Lower high school | 132 | 44.3 | 166 | 55.7 | 0.002 |

| High school or higher | 5 | 15.6 | 27 | 84.4 | ||

| Marital status | Other | 52 | 43.3 | 68 | 56.7 | 0.612 |

| Marital | 85 | 40.5 | 125 | 59.5 | ||

| Economic status | Poor | 19 | 70.4 | 8 | 29.6 | 0.001 |

| No poor | 118 | 38.9 | 185 | 61.1 | ||

| Sleep disturbance | Yes | 131 | 48.0 | 142 | 52.0 | <0.001 |

| No | 6 | 10.5 | 51 | 89.5 | ||

| Item | Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 7. Are you in good spirits most of the time? | 0.748 | ||||

| 8. Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? | 0.671 | ||||

| 6. Are you bothered by thoughts you can’t get out of your head? | 0.664 | ||||

| 13. Do you frequently worry about the future? | 0.658 | ||||

| 9. Do you feel happy most of the time? | 0.653 | ||||

| 4. Do you often get bored? | 0.542 | ||||

| 16. Do you feel downhearted and blue? | 0.531 | ||||

| 15. Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? | 0.687 | ||||

| 5. Are you hopeful about the future? | 0.667 | ||||

| 19. Do you find life very exciting? | 0.653 | ||||

| 21. Do you feel full of energy? | 0.615 | ||||

| 23. Do you think that most people are better off than you are? | 0.708 | ||||

| 24. Do you frequently get upset over little things? | 0.664 | ||||

| 18. Do you worry a lot about the past? | 0.556 | ||||

| 25. Do you frequently feel like crying? | 0.526 | ||||

| 17. Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? | 0.510 | ||||

| 12. Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things? | 0.746 | ||||

| 28. Do you prefer to avoid social gatherings? | 0.698 | ||||

| 2. Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? | 0.562 | ||||

| 30. Is your mind as clear as it used to be? | 0.795 | ||||

| 14. Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most? | 0.792 | ||||

| Percent Variance (%) | 33.57 | 5.73 | 5.07 | 4.62 | 3.88 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, K.T.; Nguyen, P.M.; Nguyen, N.M.; Ly, C.L.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, M.T.T.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen, X.T.K.; Duong, N.H.P.; et al. Vietnamese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (30 Items): Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6040116

Nguyen TV, Nguyen KT, Nguyen PM, Nguyen NM, Ly CL, Nguyen T, Nguyen MTT, Le HM, Nguyen XTK, Duong NHP, et al. Vietnamese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (30 Items): Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation. Geriatrics. 2021; 6(4):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6040116

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Thong Van, Kien Trung Nguyen, Phuong Minh Nguyen, Nghiem Minh Nguyen, Chi Lan Ly, Thang Nguyen, Minh Thi Tuyet Nguyen, Hoang Minh Le, Xuyen Thi Kim Nguyen, Nghi Huynh Phuong Duong, and et al. 2021. "Vietnamese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (30 Items): Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation" Geriatrics 6, no. 4: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6040116

APA StyleNguyen, T. V., Nguyen, K. T., Nguyen, P. M., Nguyen, N. M., Ly, C. L., Nguyen, T., Nguyen, M. T. T., Le, H. M., Nguyen, X. T. K., Duong, N. H. P., Veith, R. C., & Nguyen, T. V. (2021). Vietnamese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (30 Items): Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation. Geriatrics, 6(4), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6040116