But Is Ageing Really All Bad? Conceptualising Positive Ageing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Conceptualising Positive Ageing

2.2. Positive Ageing: Expansion and Application

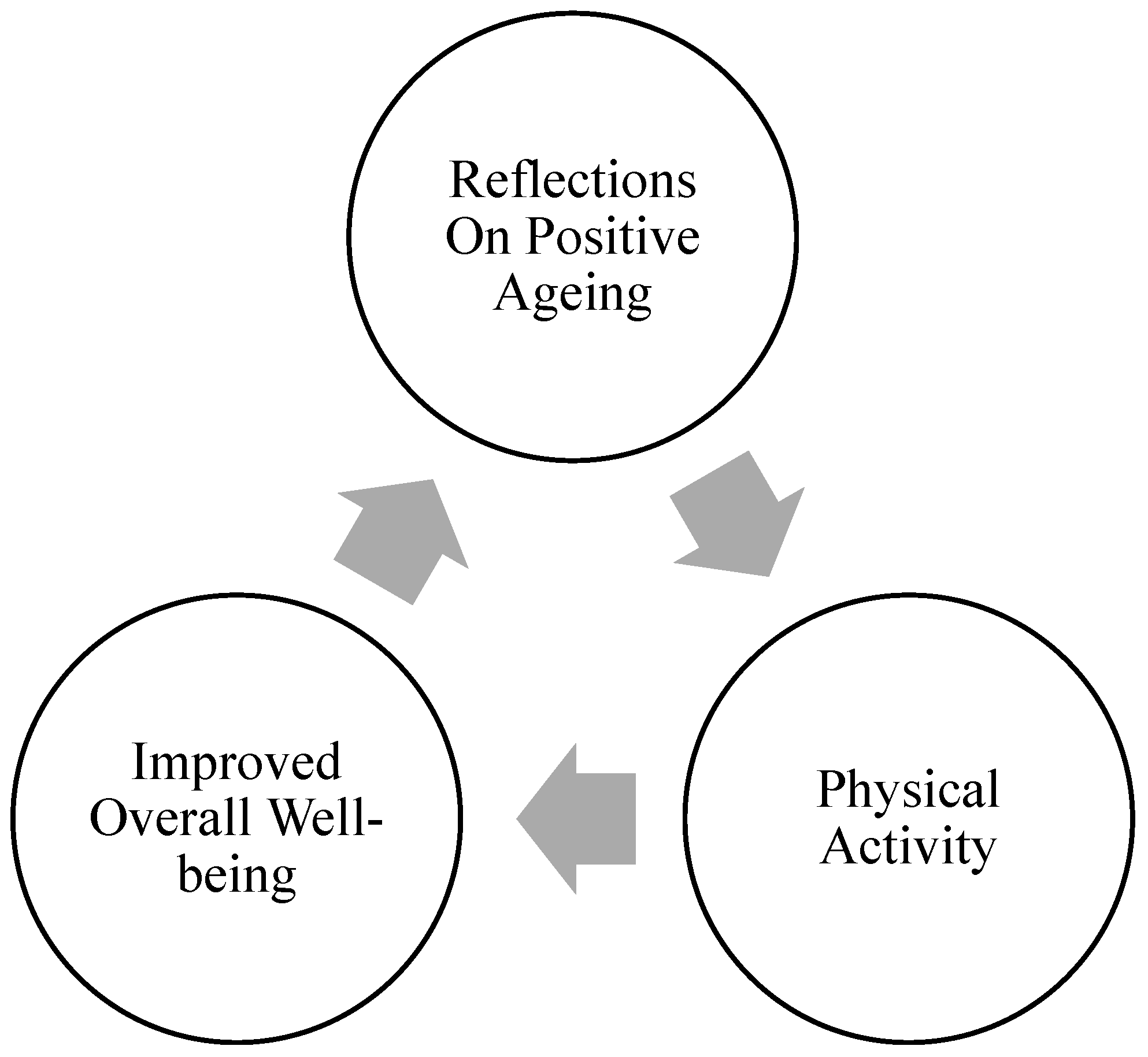

2.3. Cyclic Model of Positive Ageing

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J. Characterizing the heterogeneity of aging: A vision for a staging system for aging. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 513557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosco, T.D.; Prina, A.M.; Perales, J.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Brayne, C. Operational definitions of successful aging: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depp, C.A.; Jeste, D.V. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 1987, 237, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Cohen, R.D. Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Y.; Frick, K.D.; Phelan, E.A. Can successful aging and chronic illness coexist in the same individual? A multidimensional concept of successful aging. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009, 10, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Wister, A.; Brayne, C.; Howse, K. Psychosocial aspects of successful ageing and resilience: Critique, integration and implications/Aspectos psicológicos del envejecimiento exitoso y la resiliencia: Crítica, integración e implicaciones. Estud. Psicol. 2018, 39, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, J.D.; Cooney, T.M. Examining Rowe and Kahn’s Concept of Successful Aging: Importance of Taking a Life Course Perspective. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Calasanti, T. Critical perspectives on successful aging: Does it “appeal more than it illuminates”? Gerontologist 2015, 55, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, S. Permanent personhood or meaningful decline? Toward a critical anthropology of successful aging. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 29, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Iliffe, S. Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Bond, M.J. Comparisons of the utility of researcher--defined and participant--defined successful ageing. Australas. J. Ageing 2016, 35, E7–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Feng, Q.; Sautter, J.M.; Yang, F.; Ma, L.; Zhen, Z. Concordance and discordance of self-rated and researcher-measured successful aging: Subtypes and associated factors. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.M.; Auais, M.; Bélanger, E.; Phillips, S.P. Comparison of self-rated and objective successful ageing in an international cohort. Ageing Soc. 2018, 39, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, C.J.; Enticott, J.C.; Thomas, S.A.; Kendig, H.A.L. Trajectories of ageing well among older Australians: A 16-year longitudinal study. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1581–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell, N.; Hinterlong, J.; Sherraden, M. (Eds.) Productive Aging: Concepts and Challenges; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, A.M.L.; Ng, S.H.; Woo, J.; Kwan, A.Y.H. Positive ageing: The views of middle-aged and older adults in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2006, 26, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.K.; Cheng, M.Y.; Pheh, K.S. A thematic analysis of older adult’s perspective of successful ageing. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 10999–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, M.; Berridge, C. Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; GARCIA, L.F.; Abarca, D.; Blanc, E.; Efklides, A.; Moraitou, D.; Kornfeld, R.; Lerma, A.J.; Mendoza-Numez, V.M.; Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N.M.; et al. The concept of ‘ageing well’ in ten Latin American and European countries. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active ageing: A policy framework. Aging Male 2002, 5, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tur, L. Fostering well-being in the elderly: Translating theories on positive aging to practical approaches. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 517226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomaeus, J.D.; Van Agteren, J.E.; Iasiello, M.P.; Jarden, A.; Kelly, D. Positive aging: The impact of a community wellbeing and resilience program. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeble-Ramsay, D. Exploring the concept of ‘positive ageing’in the UK workplace—A literature review. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, J.; Dadswell, A. The role of religion, spirituality and/or belief in positive ageing for older adults. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, L.M.; Howe, M.J.; Francis, J.; Montoya, Y.; Gutwein, M. Latinos and the pandemic: Results from the national social life, health, and aging project—COVID-19 study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornadt, A.E.; Kessler, E.M.; Wurm, S.; Bowen, C.E.; Gabrian, M.; Klusmann, V. Views on ageing: A lifespan perspective. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Lo, C.; Lee, H.J.; Moon, S.; Webber, B.; Badham, S.; Paterson, J. “I’m more confident now than I have ever used to be”: A qualitative investigation of positive ageing in British older adults. Gerontologist 2025, 65, gnaf149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badache, A.C.; Hachem, H.; Mäki-Torkko, E. The perspectives of successful ageing among older adults aged 75+: A systematic review with a narrative synthesis of mixed studies. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 1203–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.W.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; De Vries, N.K. Cross-cultural comparison between academic and lay views of healthy ageing: A literature review. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 1373–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.J.; Claunch, K.D.; Verdeja, M.A.; Dungan, M.T.; Anderson, S.; Clayton, C.K.; Thacker, E.L. What does “successful aging” mean to you?—Systematic review and cross-cultural comparison of lay perspectives of older adults in 13 countries, 2010–2020. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2020, 35, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teater, B.; Chonody, J.M. How do older adults define successful aging? A scoping review. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plugge, M. Successful ageing in the oldest old: Objectively and subjectively measured evidence from a population-based survey in Germany. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, L.; Van Kessel, P.; Huang, C.; Clancy, L.; Gubbala, S. What Makes Life Meaningful? In Views from 17 Advanced Economies; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Donizzetti, A.R.; Capone, V. Ageism and the Pandemic: Risk and Protective Factors of Well-Being in Older People. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Hawkley, L.C.; Waite, L.J.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, G. The Philosophy of Well-Being: An Introduction; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.S.A.; Chirkov, V. Culture, Self, and Autonomy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, H.R. Is religion good for your health? Gerontologist 2006, 46, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Joshanloo, M.; Weijers, D. Ideal personhood through the ages: Tracing the genealogy of the modern concepts of wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1494506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.; Avant, K. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 5th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B.L. Concept development in nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. In Concept Analysis: An Evolutionary View, 2nd ed.; Rodgers, B.L., Knafl, K.A., Eds.; Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.A.; Badham, S.; Vizcaino-Vickers, S.; Fino, E. Exploring older adults’ subjective views on aging positively: Development and validation of the positive aging scale. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badham, S.P. The older population is more cognitively able than in the past and age-related deficits in cognition are diminishing over time. Dev. Rev. 2024, 72, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, L.F.; Buchanan, D. Successful aging: Considering non-biomedical constructs. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De São José, J.M.; Timonen, V.; Amado, C.A.F.; Santos, S.P. A critique of the Active Ageing Index. J. Aging Stud. 2017, 40, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardelli, G.; Roncaglione, C.; Damanti, S.; Mari, D.; Cesari, M.; Marcucci, M. Adapted physical activity to promote active and healthy ageing: The PoliFIT pilot randomized waiting list-controlled trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, A.; Rissel, C.; Howard, K.; Tong, A.; Merom, D.; Smith, S.; Sherrington, C. Health coaching and pedometers to enhance physical activity and prevent falls in community-dwelling people aged 60 years and over: Study protocol for the Coaching for Healthy AGEing (CHAnGE) cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, L.; Nelis, S.M.; Jones, I.R.; Hindle, J.V.; Thom, J.M.; Nixon, J.A.; Whitaker, C.J. The Agewell trial: A pilot randomised controlled trial of a behaviour change intervention to promote healthy ageing and reduce risk of dementia in later life. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Nehrkorn-Bailey, A.; Tseng, H.Y. Psychological interventions targeting adults’ subjective views of aging. Subj. Views Aging Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 33, 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, C.; O’ Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, J. Physiology of Exercise and Healthy Aging; Taylor, A.W., Johnson, M.J., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Asia: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.A.; Condominas, E.; Sanchez-Niubo, A.; Olaya, B.; Koyanagi, A.; de Miquel, C.; Haro, J.M. Physical activity participation decreases the risk of depression in older adults: The ATHLOS population-based cohort study. Sports Med.-Open 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlo, L.; Windsor, T.D. Older and more mindful? age differences in mindfulness components and well-being. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demnitz-King, H.; Gonneaud, J.; Klimecki, O.M.; Chocat, A.; Collette, F.; Dautricourt, S.; Medit-Ageing Research Group. Association of self-reflection with cognition and brain health in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neurology 2022, 99, e1422–e1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Kim, S.G.; Khil, T.; Shin, M.; You, J.H.; Jeon, S.; Kim, J. U Psycho-electrophysiological benefits of forest therapies focused on qigong and walking with elderly individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.C.; Wu, C.L.; Liu, H.T. Effect of a multi-disciplinary active aging intervention among community elders. Medicine 2021, 100, e28314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Definition | Components | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful Ageing | High physical, psychological, and social functioning in old age without major diseases [5] |

|

|

|

| Active Ageing | The process of optimising opportunities for health, participation, and security, in order to enhance quality of life as people age [23] |

|

|

|

| Healthy Ageing | The process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age [17] |

|

|

|

| Ageing Well | Continuing to live in the community with good physical and psychological health [16] |

|

|

|

| Productive Ageing | The involvement of older adults in activities that contribute to their own well-being and the well-being of others or society. including paid and unpaid work, volunteering, and social participation [18] |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, M.S.-A.; Webber, B.; Badham, S.P.; Krägeloh, C.U.; Capone, V.; Donizzetti, A.R.; Joshanloo, M.; Harsányi, S.G.; Kovács, M.; Hellis, E. But Is Ageing Really All Bad? Conceptualising Positive Ageing. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060151

Park MS-A, Webber B, Badham SP, Krägeloh CU, Capone V, Donizzetti AR, Joshanloo M, Harsányi SG, Kovács M, Hellis E. But Is Ageing Really All Bad? Conceptualising Positive Ageing. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(6):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060151

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Miriam Sang-Ah, Blake Webber, Stephen P. Badham, Christian U. Krägeloh, Vincenza Capone, Anna Rosa Donizzetti, Mohsen Joshanloo, Szabolcs Gergő Harsányi, Monika Kovács, and Emily Hellis. 2025. "But Is Ageing Really All Bad? Conceptualising Positive Ageing" Geriatrics 10, no. 6: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060151

APA StylePark, M. S.-A., Webber, B., Badham, S. P., Krägeloh, C. U., Capone, V., Donizzetti, A. R., Joshanloo, M., Harsányi, S. G., Kovács, M., & Hellis, E. (2025). But Is Ageing Really All Bad? Conceptualising Positive Ageing. Geriatrics, 10(6), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060151