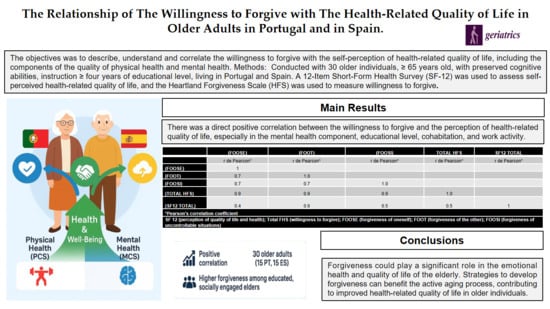

The Relationship Between Willingness to Forgive and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Portugal and Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Cognitive Preservation Criterion

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Sociodemographic Characterization

2.5. Assessment of Self-Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life

2.6. Assessment of Willingness to Forgive

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profile

3.2. Overall Assessment of Self-Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life and Willingness to Forgive

3.3. Evaluation of Self-Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life and Willingness to Forgive According to Sociodemographic Variables

3.4. Evaluation of the Variation Self-Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life Scores (SF-12) and Its Physical Health (PCS) and Mental Health (MCS) Components, Stratified by Willingness for Forgiveness (HFS) and Its Different Subscales

3.5. Assessment of the Correlation of Self-Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-12) and Its Physical Health (PCS) and Mental Health (MCS) Components with Willingness for Total Forgiveness (HFS) and Its Different Subscales

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ES | Spain |

| ESSSM | Escola Superior de Saúde de Santa Maria |

| FOOSE | Forgiveness of oneself |

| FOOSI | Forgiveness of situations that one does not control |

| FOOT | Forgiveness of others |

| HFS | Heartland Forgiveness Scale |

| Total HFS | Willingness to Forgive |

| MCS | Mental component |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MOCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PT | Portugal |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PCS | Physical component |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SF-12 | 12-Item Short-Form—Health Status Assessment |

| SF-12 Total | Self-Perceived Quality of Life |

| SF-36 | 36 Short-Form—Health Status Assessment |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Worthington, E.L., Jr. (Ed.) Initial Questions About the Art and Science of Forgiving. In Handbook of Forgiveness; Routledge: New York, UK, USA, 2005; pp. 1–622. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, R.D. Forgiveness Is a Choice: A Step-by-Step Process for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J.C.A. The Extraordinary Capacity to Forgive: Implications in the (Re)Construction of Happiness. Master’s Thesis, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, K.R.; Stackhouse, M.; Boon, S.D.; Comstock, K.; Ross, R. Meta-analytic connections between forgiveness and health: The moderating effects of forgiveness-related distinctions. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismaya, A.; Gopi, A.; Romate, J. Psychological interventions to promote self-forgiveness: A systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemand, M.; Steiner, M.; Hill, P.L. Effects of a forgiveness intervention for older individuals. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, J.; Serrano, M.I.; Giménez, I.; Noriega, C. Forgiveness interventions for older individuals: A review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, C.; Krause, N. Unforgiveness, rumination and depressive symptoms among older individuals. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.P.R.; Vieira, M.; Mendonça, S.H.F. Interpersonal forgiveness and health-related quality of life in the elderly: Scoping review. In 11th International Seminar on Nursing Research Proceedings; Vieira, M., Neves-Amado, J., Deodato, S., Eds.; Institute of Health Sciences–Catholic University of Portugal: Porto, Portugal, 2017; p. 137. ISBN 978-989-97041-7-6. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health 2016–2020: Towards a World in Which Everyone Can Live a Long and Healthy Life. Geneva: Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly. 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA73/A73_INF2-en.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Demographic Trends. In Society at A Glance 2024: OECD Social Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M. Contribution of Neuropsychology to the Study of Dementias. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Morgado, J.; Rocha, C.S.; Maruta, C.; Guerreiro, M.; Martins, I.P. New normative scores of the Mini Mental State Examination. Sinapse 2009, 9, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Gutiérrez, S.; Fernández-Rodríguez, E.J.; Sánchez-Gómez, C.; García-Martín, A.; Barbero-Iglesias, F.J.; Sánchez Aguadero, N. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial: Effect of an everyday cognition training program on cognitive function, emotional state, frailty and functioning in older individuals without cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Araneda, A.; Behrens, M.I. Validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment instrument in Spanish in adults over 60 years of age. Neurology 2019, 34, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.L. Creation of the Portuguese version of the MOS SF-36. Part I: Cultural and linguistic adaptation. Acta Med. Port. 2000, 13, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.L. Creation of the Portuguese version of the MOS SF-36. Part II: Validation tests. Acta Med. Port. 2000, 13, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.L.; Santana, P. Perception of health status and health-related quality of life of the active population: Contribution to the definition of Portuguese norms. Rev. Port. Saude Publica 2003, 21, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Antó, J.M. The Spanish version of the SF-36 health survey: An instrument for measuring clinical outcomes. Med. Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L. The Important Thing Is Health: Study of Adaptation of an Instrument to Assess Health Status; Merck Sharp & Dohme Foundation: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Villarroel, P.; Silva, J.; Celis-Atenas, K.; Pavez, P. Evaluation of the SF-12 questionnaire: Verification of the usefulness of the mental health scale. Rev. Med. Chil. 2014, 142, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Rajmil, L.; Rebollo, P.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Quintana, J.M.; Santed, R.; Valderas, J.M.; Ribera, A.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; et al. The Spanish SF-36 Health Questionnaire: A Decade of Experience and New Developments. Gac. Sanit. 2005, 19, 135–150. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-91112005000200007&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 27 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.Y.; Snyder, C.R.; Hoffman, L.; Michael, S.T.; Rasmussen, H.N.; Billings, L.S.; Heinze, L.; Neufeld, J.E.; Shorey, H.S.; Roberts, J.C. Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. J. Pers. 2005, 73, 313–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heartland Forgiveness Scale. 2020. Available online: www.heartlandforgiveness.com (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Ikedo, F.; Castro, L.; Fraguas, S.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the European Portuguese version of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Giunzioni, K.; Prieto-Ursúa, M.; Fernández-Belinchón, C.; Luque-Reca, O. Measuring Forgiveness: Psychometric Properties of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale in the Spanish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.E.; Ho, M.Y.; Griffin, B.J.; Bell, C.; Hook, J.N.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; DeBlaere, C.; Worthington, E.L.; Westbrook, C.J. Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: A meta-analytic review. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Zhu, T.; Min, Y.; Ji, M. The Older, the More Forgiving? Characteristics of Forgiveness of Chinese Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 732863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barros-Oliveira, J.H. Happiness, optimism, hope and forgiveness in young adults, adults and the elderly. Psychologica 2010, 52, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleta, K.; Mróz, J. Gender differences in forgiveness and its affective correlates. J. Relig. Health 2022, 61, 2819–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A.; Sousa, P.; Moura, A.; Lopes, L.; Silva, C.; Robinson, N.; Machado, J.; Moreira, A. The Effect of Auriculotherapy on Situational Anxiety Trigged by Examinations: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, L.; Extremera, N. Forgiveness and health-related quality of life in older individuals: Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies as mediators. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, E.; Ortega, A.R.; Chamorro, A.; Colmenero, J.M. A program of positive intervention in the elderly: Memories, gratitude and forgiveness. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulk, M.A.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Fitzgerald, J. Mindfulness-based forgiveness groups for older individuals. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2017, 60, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. The Moderation Effects of Self-Construal Between Dispositional Mindfulness and Interpersonal Forgiveness. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 2470–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struthers, C.W.; van Monsjou, E.; Ayoub, M.; Guilfoyle, J.R. Fit to Forgive: Effect of Mode of Exercise on Capacity to Override Grudges and Forgiveness. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Portugal (n = 15) | Spain (n = 15) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p * | |

| SEX | |||||

| Woman | 11 | 73 | 11 | 73 | 0.50 |

| Man | 4 | 27 | 4 | 27 | |

| AGE GROUP | |||||

| 65–69 | 4 | 27 | 4 | 27 | |

| 70–74 | 9 | 60 | 3 | 20 | |

| 75–79 | 1 | 6.5 | 5 | 33.5 | 0.50 |

| 80–84 | 1 | 6.5 | 2 | 13 | |

| ≥85 | 0.0 | 0 | 1 | 6.5 | |

| MARITAL STATUS | |||||

| Civilly Married or in “Facto Union” | 8 | 53 | 8 | 53 | |

| Divorced | 6 | 40 | 4 | 27 | 0.50 |

| Widower | 1 | 7 | 3 | 20 | |

| EDUCATIONAL LEVEL | |||||

| Basic Education—1st Cycle to 4th year | 6 | 40 | 5 | 34 | |

| Basic Education—2nd Cycle to 5th–6th Grade | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | |

| Basic Education—3rd Cycle to 7th–9th Grade | 2 | 13 | 2 | 13 | |

| Secondary Education—10th–12th grade | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 0.40 |

| Higher Education—Bachelor’s degree (3 years) | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Higher Education—Bachelor’s degree (4 years) | 3 | 20 | 2 | 13 | |

| Higher Education—Master’s degree | 2 | 13 | 1 | 7 | |

| Higher Education—PhD | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | |

| WORKING STATUS | |||||

| Employee | 3 | 20 | 0 | 0 | |

| From Home | 1 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 0.40 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | |

| Retired | 11 | 73 | 12 | 80 | |

| COHABITATION | |||||

| Alone | 6 | 40 | 6 | 40 | |

| Spouse | 7 | 46 | 7 | 46 | |

| Spouse and Children | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0.50 |

| Children and/or Grandchildren | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sister | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Portugal (n = 15) | Spain (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average ± SD | Average ± SD | p * | |

| SF-12 Score Total % | 71.2 ±18.9 | 73.3 ± 20.77 | 0.28 |

| Physical component (PCS) % | 73.3 ± 18.07 | 75.3 ± 24.07 | 0.24 |

| Mental component (MCS) % | 69.5 ± 24.46 | 72.2 ± 21.48 | 0.32 |

| FHS | |||

| Score Total | 86.9 ± 27.39 | 92.5 ± 18.66 | 0.25 |

| FOOSE | 29.7 ± 8.97 | 29.0 ± 7.24 | 0.41 |

| FOOT | 29.5 ± 8.85 | 32.6 ± 7.3 | 0.15 |

| FOOSI | 27.7 ± 10.76 | 30.9 ± 8.64 | 0.18 |

| Portugal and Spain (n = 30) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 Total % | PCS % | MCS % | ||||

| Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Woman | 68.8 ± 17.75 | 0.08 | 73.4 ± 17.17 | 0.38 | 65.6 ± 22.16 | 0.01 |

| Man | 81.8 ± 22.26 | 76.9 ± 30.36 | 85.1 ± 18.35 | |||

| Age group | ||||||

| 65 to 75 years old | 70 ± 20.25 | 0.14 | 71.8 ± 22.51 | 0.08 | 68.9 ± 23.14 | 0.22 |

| ≥76 years old | 78.3 ± 17.16 | 81.3 ± 12.87 | 76.1 ± 21.87 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Civilly Married/“Facto Union” | 74.4 ± 21.81 | 72.8 ± 27.04 | 0.33 | 75.6 ± 22.48 | 0.11 | |

| Widowed or Divorced | 69.7 ± 17.03 | 0.25 | 76 ± 11.32 | 65.4 ± 22.44 | ||

| Educational Level | ||||||

| 4 to 11 years old | 70.4 ± 20.13 | 0.25 | 72.9 ± 20.97 | 0.32 | 68.7 ± 25.02 | 0.23 |

| ≥12 years old | 75.4 ± 19 | 76.6 ± 21.78 | 74.5 ± 18.41 | |||

| Working Status | ||||||

| Retired or Home-Based | 69.6 ± 19.66 | 3.00 | 72 ± 21.54 | <0.01 | 68 ± 23.04 | <0.01 |

| Working or Unemployed | 89.5 ± 3.32 | 89.5 ± 4.04 | 89.3 ± 4.27 | |||

| Cohabitation | ||||||

| Live Alone | 67.8 ± 17.6 | 0.14 | 75.6 ± 11.83 | 0.38 | 62.4 ± 22.90 | 0.05 |

| Family (husband/wife and/or children) | 75.2 ± 20.67 | 73.4 ± 25.60 | 76.4 ± 21.29 | |||

| Live | ||||||

| Portugal—Urban Area | 71.2 ± 18.9 | 0.28 | 73.3 ± 18.07 | 0.24 | 69.5 ± 24.46 | 0.32 |

| Spain—Urban Area | 73.3 ± 20.77 | 75.3 ± 24.07 | 72.2 ± 21.48 | |||

| Portugal and Spain (n = 30) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total FHS | FOOSE | FOOT | FOOSI | |||||

| Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Woman | 87.8 ± 24.39 | 0.21 | 28.3 ± 8.20 | 0.11 | 30.5 ± 8.32 | 0.26 | 29 ± 10.59 | 0.36 |

| Man | 94.9 ± 20.09 | 32.1 ± 7.22 | 32.6 ± 7.85 | 30.1 ± 7.40 | ||||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 65 to 75 years old | 88.5 ± 22.86 | 0.34 | 29.8 ± 7.42 | 0.33 | 29.3 ± 7.64 | 0.02 | 29.5 ± 9.59 | 0.42 |

| ≥76 years old | 92.8 ± 25.47 | 28.1 ± 9.93 | 36 ± 7.76 | 28.6 ± 10.74 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Civilly Married/“Facto Union” | 91.3 ± 20.79 | 0.35 | 29.8 ± 8.17 | 0.34 | 31.6 ± 7.49 | 0.34 | 29.9 ± 8.11 | 0.35 |

| Widowed or Divorced | 87.9 ± 26.38 | 28.8 ± 8.11 | 30.5 ± 9.04 | 28.6 ± 11.59 | ||||

| Educational Level | ||||||||

| 4 to 11 years | 84.2 ± 22.13 | 0.04 | 27 ± 7.21 | 0.02 | 30.7 ± 8.58 | 0.36 | 26.5 ± 9.35 | 0.01 |

| ≥12 years | 99.2 ± 22.86 | 33.4 ± 8.03 | 31.7 ± 7.62 | 34.1 ± 8.75 | ||||

| Working Status | ||||||||

| Retired or Home-Based | 87.5 ± 22.73 | 0.13 | 28.2 ± 7.72 | 0.02 | 30.7 ± 8.11 | 0.31 | 28.6 ± 9.75 | 0.18 |

| Working or Unemployed | 104 ± 24.12 | 37 ± 5.77 | 33.3 ± 9.07 | 33.8 ± 9.54 | ||||

| Cohabitation | ||||||||

| Live Alone | 83.8 ± 26.43 | 0.14 | 27.5 ± 7.99 | 0.15 | 29.7 ± 9.55 | 0.23 | 26.7 ± 11.41 | 0.13 |

| Family (husband/wife and/or children) | 93.6 ± 20.65 | 30.6 ± 8.02 | 32 ± 7.15 | 31 ± 8.32 | ||||

| Live | ||||||||

| Portugal—Urban Area | 86.9 ± 27.39 | 0.25 | 29.7 ± 8.97 | 0.41 | 29.5 ± 8.85 | 0.15 | 27.7 ± 10.76 | 0.18 |

| Spain—Urban Area | 92.5 ± 18.66 | 29 ± 7.24 | 32.6 ± 7.3 | 30.9 ± 8.64 | ||||

| Portugal and Spain (n = 30) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 Total % | PCS % | MCS % | ||||

| Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | Average ± SD | p * | |

| TOTAL FHS | ||||||

| 18–89 score ** | 61.1 ± 2073 | 0.01 | 66.1 ± 24.47 | 0.08 | 57.5 ± 24.65 | <0.01 |

| 90–126 score *** | 78.9 ± 15.03 | 78.1 ± 17.06 | 79.5 ± 16.47 | |||

| FHS—FOOSE | ||||||

| 06–29 score **** | 64.8 ± 21.33 | 0.01 | 70.5 ± 24.20 | 0.16 | 60.9 ± 24.76 | <0.01 |

| 30–42 score ***** | 79.7 ± 14.74 | 78.1 ± 17.06 | 80.8 ± 15.42 | |||

| FHS—FOOT | ||||||

| 06–29 score **** | 60.9 ± 20.72 | <0.01 | 64.2 ± 23.59 | 0.02 | 58.7 ± 24.40 | 0.01 |

| 30–42 score ***** | 79.8 ± 14.93 | 81.1 ± 16.33 | 78.9 ± 17.80 | |||

| FHS—FOOSI | ||||||

| 06–29 score **** | 66.1 ± 21.16 | 0.03 | 64.2 ± 24.97 | 0.08 | 64.2 ± 24.97 | 0.03 |

| 30–42 score ***** | 79.1 ± 14.98 | 79.2 ± 17.70 | 79.2 ± 16.70 | |||

| (FOOSE) | (FOOT) | (FOOSI) | TOTAL HFS | SF12 TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | |

| (FOOSE) | 1 | ||||

| (FOOT) | 0.7 | 1.0 | |||

| (FOOSI) | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||

| (TOTAL HFS) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| (SF12 TOTAL) | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| PCS | MCS | FOOSE | FOOT | FOOSI | Total HFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | r de Pearson * | |

| PCS | 1 | |||||

| MCS | 0.6 | 1 | ||||

| FOOSE | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | |||

| FOOT | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1 | ||

| FOOSI | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1 | |

| Total HFS | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, C.P.R.; Barbero-Iglesias, F.J.; Polo-Ferrero, L.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I. The Relationship Between Willingness to Forgive and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Portugal and Spain. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040090

Silva CPR, Barbero-Iglesias FJ, Polo-Ferrero L, Recio-Rodríguez JI. The Relationship Between Willingness to Forgive and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Portugal and Spain. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Cristiane Pavanello Rodrigues, Fausto J. Barbero-Iglesias, Luis Polo-Ferrero, and José I. Recio-Rodríguez. 2025. "The Relationship Between Willingness to Forgive and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Portugal and Spain" Geriatrics 10, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040090

APA StyleSilva, C. P. R., Barbero-Iglesias, F. J., Polo-Ferrero, L., & Recio-Rodríguez, J. I. (2025). The Relationship Between Willingness to Forgive and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Portugal and Spain. Geriatrics, 10(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040090