Trends and Mortality Predictors of Delirium Among Hospitalized Older Adults: A National 5-Year Retrospective Study in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Populations

2.2. Data Collections

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

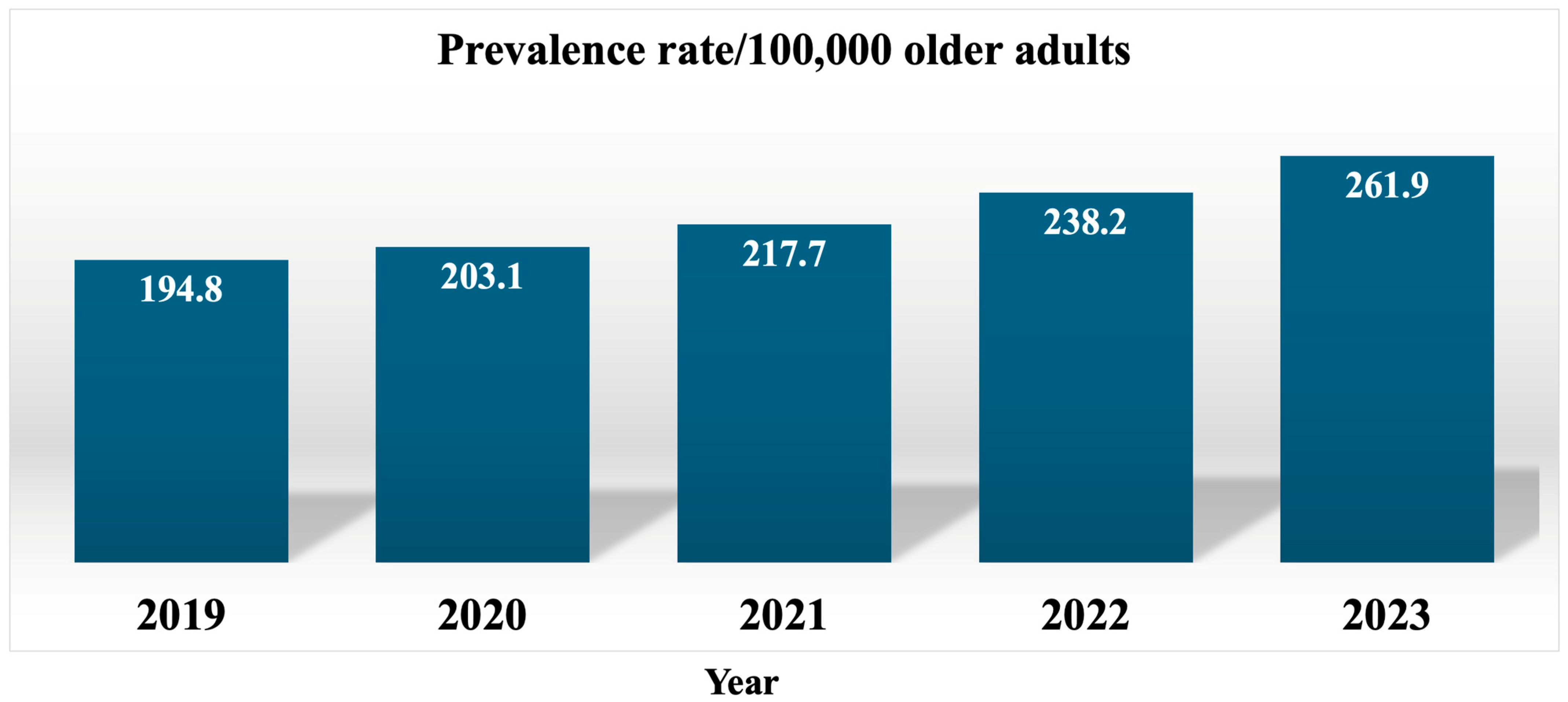

3.1. Prevalence Rates of Delirium

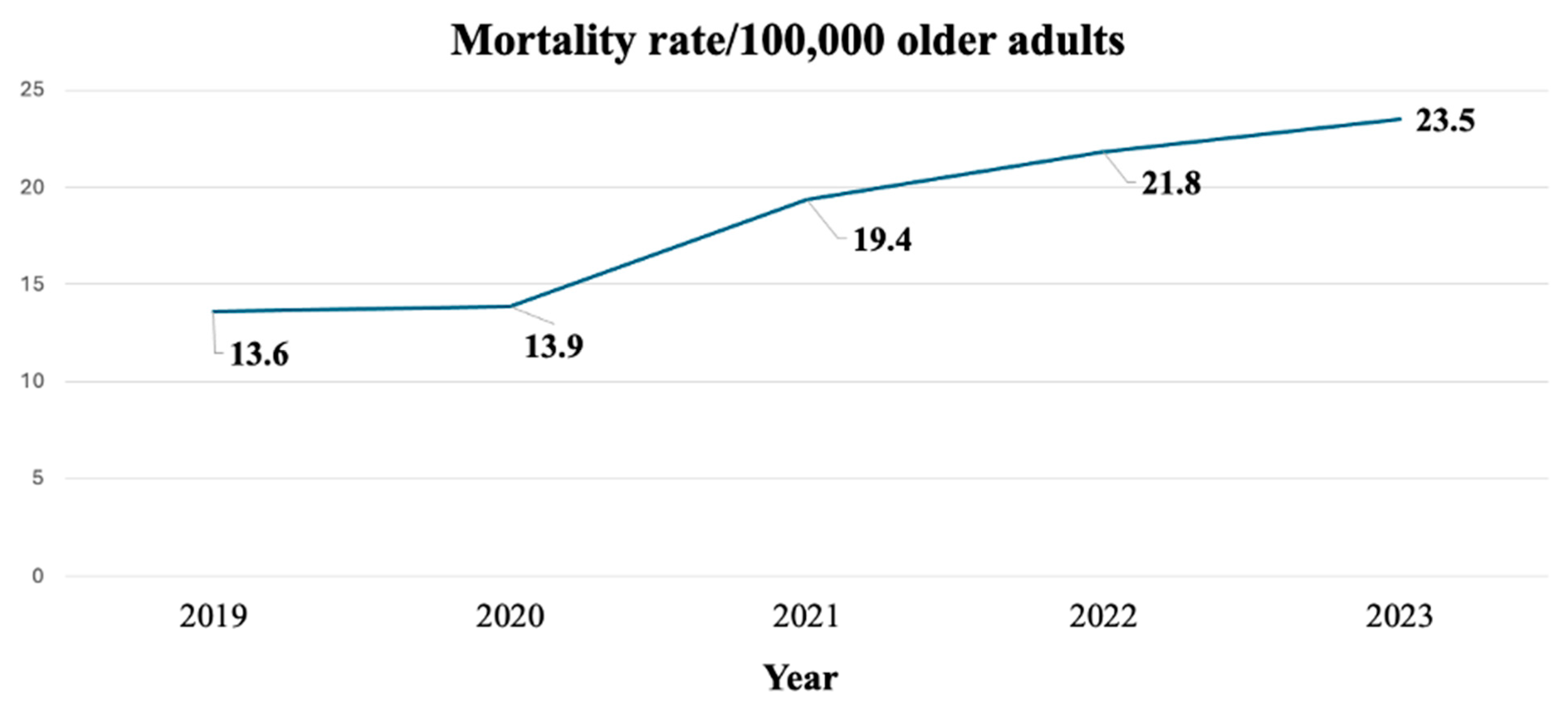

3.2. Mortality Rate at Discharge, Hospital Stay, and Healthcare Costs of Inpatients Diagnosed with Delirium

3.3. Factors Associated with Death at Discharge

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence Rates of Delirium

4.2. Consequences of Delirium

4.3. Factors Associated with Death at Discharge

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, J.E.; Mart, M.F.; Cunningham, C.; Shehabi, Y.; Girard, T.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Ely, E.W. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Alawi, A.M.; Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Maqbali, J.S. Delirium in medically hospitalized patients: Prevalence, recognition and risk factors: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellelli, G.; Brathwaite, J.S.; Mazzola, P. Delirium: A marker of vulnerability in older people. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 626127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormseth, C.H.; LaHue, S.C.; Oldham, M.A.; Josephson, S.A.; Whitaker, E.; Douglas, V.C. Predisposing and precipitating factors associated with delirium: A systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2249950. [Google Scholar]

- Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Maqbali, J.S.; Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Alawi, A.M. Delirium and its association with short- and long-term health outcomes in medically admitted patients: A prospective study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.T.; Lovett, N.G.; Smith, S.C.; Dutta, N.; Bendon, C.; Lloyd-Lavery, A.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P. Observational, longitudinal study of delirium in consecutive unselected acute medical admissions: Age-specific rates and associated factors, mortality and re-admission. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpawattana, P.; Sutra, S.; Thavornpitak, Y.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Chindaprasirt, J.; Mairieng, P. Delirium in hospitalized elderly patients of Thailand; is the figure underrecognized? J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2012, 95 (Suppl. S7), S224–S228. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Bookamana, P.; Pinyopornpanish, M.; Maneeton, B.; Lerttrakarnnon, P.; Uttawichai, K.; Jiraniramai, S. Diagnosing delirium in elderly Thai patients: Utilization of the CAM algorithm. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipanmekaporn, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Mueankwan, S.; Dendumrongkul, P.; Chittawatanarat, K.; Khongpheng, N.; Duangsoy, N. Validity and reliability of the Thai version of the Confusion Assessment Method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuladee, S.; Prachason, T. Development and validation of the Thai version of the 4 ‘A’s Test for delirium screening in hospitalized elderly patients with acute medical illnesses. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva MACPda Teixeira, J.M.F.; da Costa Pinheiro, M.C.R.; Durao, P. Delirium management in critically ill patients: An integrative review. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2023, 6, 3993–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahawneh, F.; Boss, L. Non-pharmacologic interventions for the prevention of delirium in the intensive care unit: An integrative review. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thailand Monthly Death Count Statistics. [Internet]. Available online: https://stat.bora.dopa.go.th/stat/statnew/statMONTH/statmonth/#/mainpage (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ibitoye, T.; Jackson, T.A.; Davis, D.; MacLullich, A.M.J. Trends in delirium coding rates in older hospital inpatients in England and Scotland: Full population data comprising 7.7M patients per year show substantial increases between 2012 and 2020. Delirium Commun. 2023, 2023, 84051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apuy, A.R.; Badell, C.S.; Ponce, O.J.; Ruiz, E.F.; Palomino, L.E. Unveiling the storm: Delirium coding trends among hospitalized Peruvian older adults. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2024, 18, e20240200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, T.; Pate, K.; Cochran, A.R.; Belin, L. Delirium in the era of COVID-19. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2024, 39, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Zucchelli, A.; Grande, G.; Fratiglioni, L.; Rizzuto, D. The impact of delirium on outcomes for older adults hospitalised with COVID-19. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ticinesi, A.; Cerundolo, N.; Parise, A.; Nouvenne, A.; Prati, B.; Guerra, A.; Lauretani, F.; Maggio, M.; Meschi, T. Delirium in COVID-19, epidemiology and clinical correlations in a large group of patients admitted to an academic hospital. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 2159–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitchote, A.; Tangvoraphonkchai, K.; Suebsoh, N.; Eamma, W.; Chanthonglarng, B.; Tiamkao, S.; Limpawattana, P. Under-recognition of delirium in older adults by nurses in the intensive care unit setting. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 27, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangratsamee, S.; Assanasen, J.; Praditsuwan, R.; Srinonprasert, V. Unrecognized delirium is prevalent among older patients admitted to general medical wards and lead to higher mortality rate. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2016, 99, 904–912. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli, A.; Ballarin, M.; Montalti, M.; Ceccarelli, P.; Mazzini, S.; Minotti, A.; Gori, D.; Senni, M. Delirium diagnosis, complication recognition, and treatment knowledge among nurses in an Italian local hospital: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limpawattana, P.; Worawittayakit, K.; Paopongpaiboon, P.; Chotmongkol, V.; Manjavong, M.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Eamma, W. How nurses understand and perceive delirium in older adults? J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2018, 101 (Suppl. S7), S1–S7. [Google Scholar]

- Limpawattana, P.; Paopongpaiboon, P.; Worawittayakit, K.; Manjavong, M.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Khamsai, S.; Pimporm, J. Understanding Beliefs and Knowledge gaps regarding delirium among trainee physicians in Thailand. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2018, 101 (Suppl. S7), S9–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.S.; Junnarkar, S.P.; Low, J.K.; Huey, C.W.T.; Shelat, V.G. Aging is associated with prolonged hospitalisation stay in pyogenic liver abscess-a 1, 1 propensity score matched study in elderly versus non-elderly patients. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 29, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, K.A.; Sanmartin, C.; Dasgupta, K.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ross, N. The influence of psychosocial factors on hospital length of stay among aging Canadians. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214221138442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.-C.; Su, C.-C.; Yang, D.-C. Association between the mental domain of the comprehensive geriatric assessment and prolonged length of stay in hospitalized older adults with mild to moderate frailty. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1191940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; El-Jawahri, A.R.; Litzow, M.R.; Syrjala, K.L.; Parnes, A.D.; Hashmi, S.K. A systematic review of religious beliefs about major end-of-life issues in the five major world religions. Palliat. Support. Care 2017, 15, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilmanat, K. Palliative care in Thailand: Development and challenges. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2016, 26, 262–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Jin, J.-F. Poor outcomes of delirium in the intensive care units are amplified by increasing age: A retrospective cohort study. World J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 12, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpawattana, P.; Srinonprasert, V.; Manjavong, M.; Yongrattanakit, K.; Kaiyakit, S. Comparison of the perspective of a ‘Good Death’ in older adults and physicians in training at university hospitals. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, Y.; Paul, K.; Khan, M.A.; Kumari, B.; Kumar, N.; Chatterjee, P.; Dey, A.B.; Chakrawarty, A. The evaluation of frequency and predictors of delirium and its short-term and long-term outcomes in hospitalized older adults’. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2024, 94, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, N.E.; Balas, M.C.; Morandi, A.; Ferrante, L.E.; Gill, T.M.; Ely, E.W. Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiredu, K.; Mueller, A.; McKay, T.B.; Behera, A.; Shaefi, S.; Akeju, O. Sex differences in the incidence of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery: A pooled analyses of clinical trials. Anesthesiology 2023, 139, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamchandani, K.; Schoaps, R.S.; Printz, J.; Kowaleski, J.M.; Carr, Z.J. Gender differences in the use of atypical antipsychotic medications for ICU delirium. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelmardi, M.K.; Rafaiee, R.; Talari, S.D.H.; Omali, N.A.; Hosseini, S.H. Cognitive dysfunction and survival in hospitalized patients with delirium: A 12-month prospective cohort study. Shiraz E-Med. J. 2021, 22, e109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liang, X.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Association between postoperative delirium and mortality in elderly patients undergoing hip fractures surgery: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaHue, S.C.; Douglas, V.C.; Kuo, T.; Conell, C.A.; Liu, V.X.; Josephson, S.A.; Angel, C.; Brooks, K.B. Association between inpatient delirium and hospital readmission in patients ≥ 65 years of age: A retrospective cohort study. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 14, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Age Group (Years) | Prevalence Rates | LOS (Day) | Cost (THB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 61–70 | 79.7 | 11 | 49,742 |

| 71–80 | 252.5 | 10 | 39,581 | |

| 81+ | 560.6 | 9 | 32,020 | |

| 2020 | 61–70 | 84.2 | 11 | 56,728 |

| 71–80 | 260.5 | 10 | 43,148 | |

| 81+ | 583.1 | 9 | 33,868 | |

| 2021 | 61–70 | 95.6 | 12 | 77,971 |

| 71–80 | 279.3 | 10 | 59,018 | |

| 81+ | 607.1 | 9 | 43,854 | |

| 2022 | 61–70 | 101.7 | 12 | 71,901 |

| 71–80 | 301.9 | 11 | 58,701 | |

| 81+ | 686.4 | 9 | 47,498 | |

| 2023 | 61–70 | 110.0 | 11 | 65,202 |

| 71–80 | 330.7 | 10 | 49,857 | |

| 81+ | 767.1 | 9 | 38,640 |

| Year | Age Group | Mortality Rates | LOS (Day) | Cost (THB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 61–70 | 6.7 | 23 | 131,252 |

| 71–80 | 18.4 | 26 | 116,069 | |

| 81+ | 35.9 | 18 | 85,065 | |

| 2020 | 61–70 | 6.5 | 21 | 137,646 |

| 71–80 | 17.4 | 20 | 107,906 | |

| 81+ | 37.9 | 20 | 96,861 | |

| 2021 | 61–70 | 9.8 | 19 | 181,056 |

| 71–80 | 23.6 | 19 | 157,977 | |

| 81+ | 51.0 | 18 | 124,791 | |

| 2022 | 61–70 | 10.2 | 22 | 175,667 |

| 71–80 | 25.7 | 22 | 162,935 | |

| 81+ | 62.9 | 18 | 124,559 | |

| 2023 | 61–70 | 10.9 | 21 | 152,229 |

| 71–80 | 27.8 | 22 | 132,886 | |

| 81+ | 68.1 | 16 | 89,274 |

| Factors | Crude OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||||

| 61–70 | - | - | 1 | - |

| 71–80 | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | <0.05 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 0.06 |

| 81+ | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | <0.05 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | <0.05 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | - | - | - | - |

| Women | 1.38 (1.33–1.44) | <0.05 | 1.13 (1.08–1.18) | <0.05 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| Respiratory disease | 2.55 (2.45–2.66) | <0.05 | 2.72 (2.55–2.91) | <0.05 |

| Neurological disease | 0.62 (0.58–0.67) | <0.05 | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 0.91 |

| Genitourinary disease | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 0.47 | - | - |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.27 (1.21–1.34) | <0.05 | 1.68 (1.56–1.81) | <0.05 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | 0.57 | - | - |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 0.58 (0.53–0.64) | <0.05 | 0.61 (0.55–0.68) | <0.05 |

| Metabolic disease | 0.51 (0.46–0.55) | <0.05 | 1.02 (0.92–1.12) | 0.74 |

| Systemic infection/septicemia | 1.28 (1.17–1.43) | <0.05 | 2.08 (1.86–2.33) | <0.05 |

| Malignancy | 2.87 (2.69–3.07) | <0.05 | 2.97 (2.72–3.24) | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manjavong, M.; Limpawattana, P.; Chindaprasirt, J.; Wareechai, P. Trends and Mortality Predictors of Delirium Among Hospitalized Older Adults: A National 5-Year Retrospective Study in Thailand. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040088

Manjavong M, Limpawattana P, Chindaprasirt J, Wareechai P. Trends and Mortality Predictors of Delirium Among Hospitalized Older Adults: A National 5-Year Retrospective Study in Thailand. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleManjavong, Manchumad, Panita Limpawattana, Jarin Chindaprasirt, and Poonchana Wareechai. 2025. "Trends and Mortality Predictors of Delirium Among Hospitalized Older Adults: A National 5-Year Retrospective Study in Thailand" Geriatrics 10, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040088

APA StyleManjavong, M., Limpawattana, P., Chindaprasirt, J., & Wareechai, P. (2025). Trends and Mortality Predictors of Delirium Among Hospitalized Older Adults: A National 5-Year Retrospective Study in Thailand. Geriatrics, 10(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040088