COVID-19 and Mental Distress and Well-Being Among Older People: A Gender Analysis in the First and Last Year of the Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Variables and Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

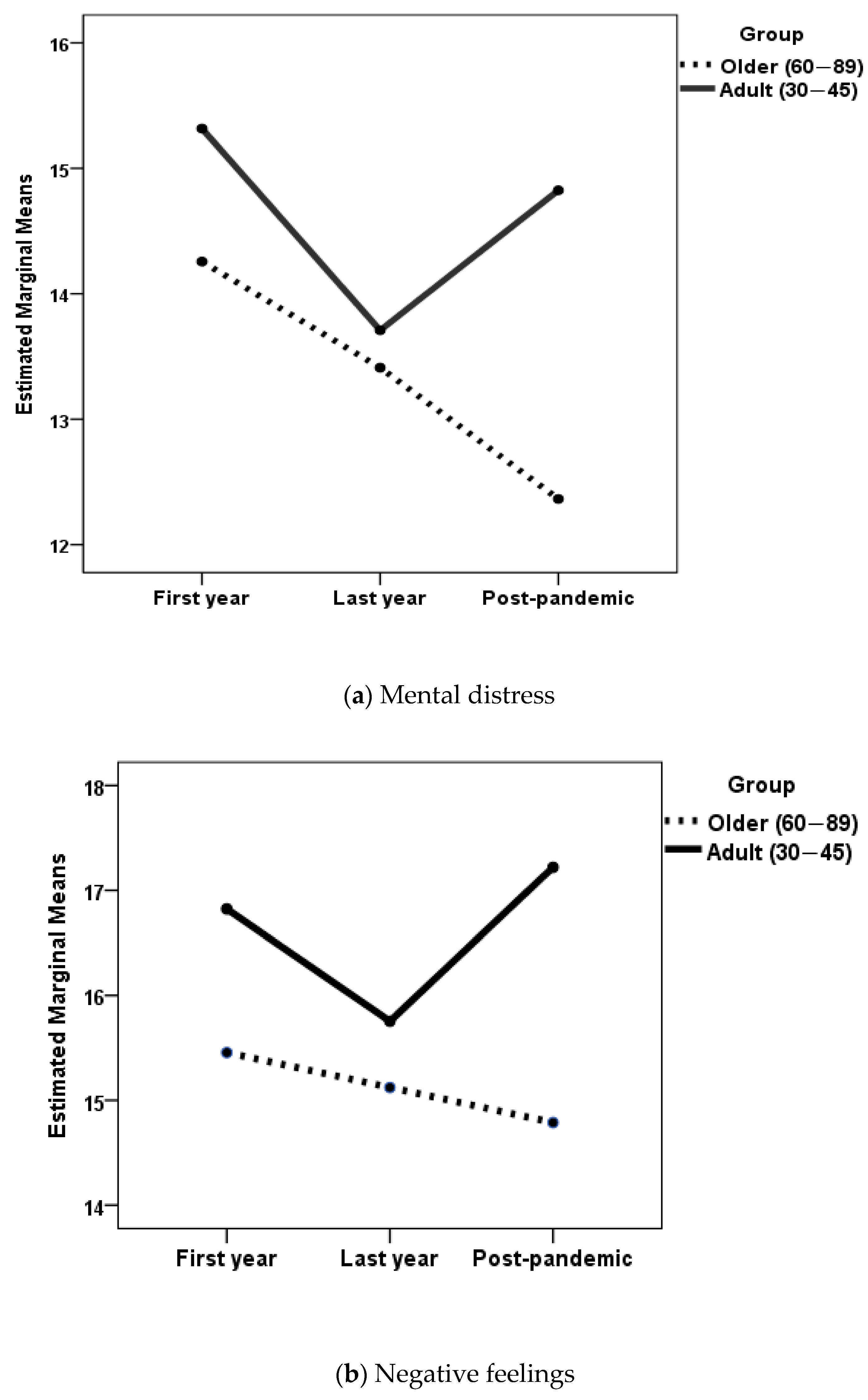

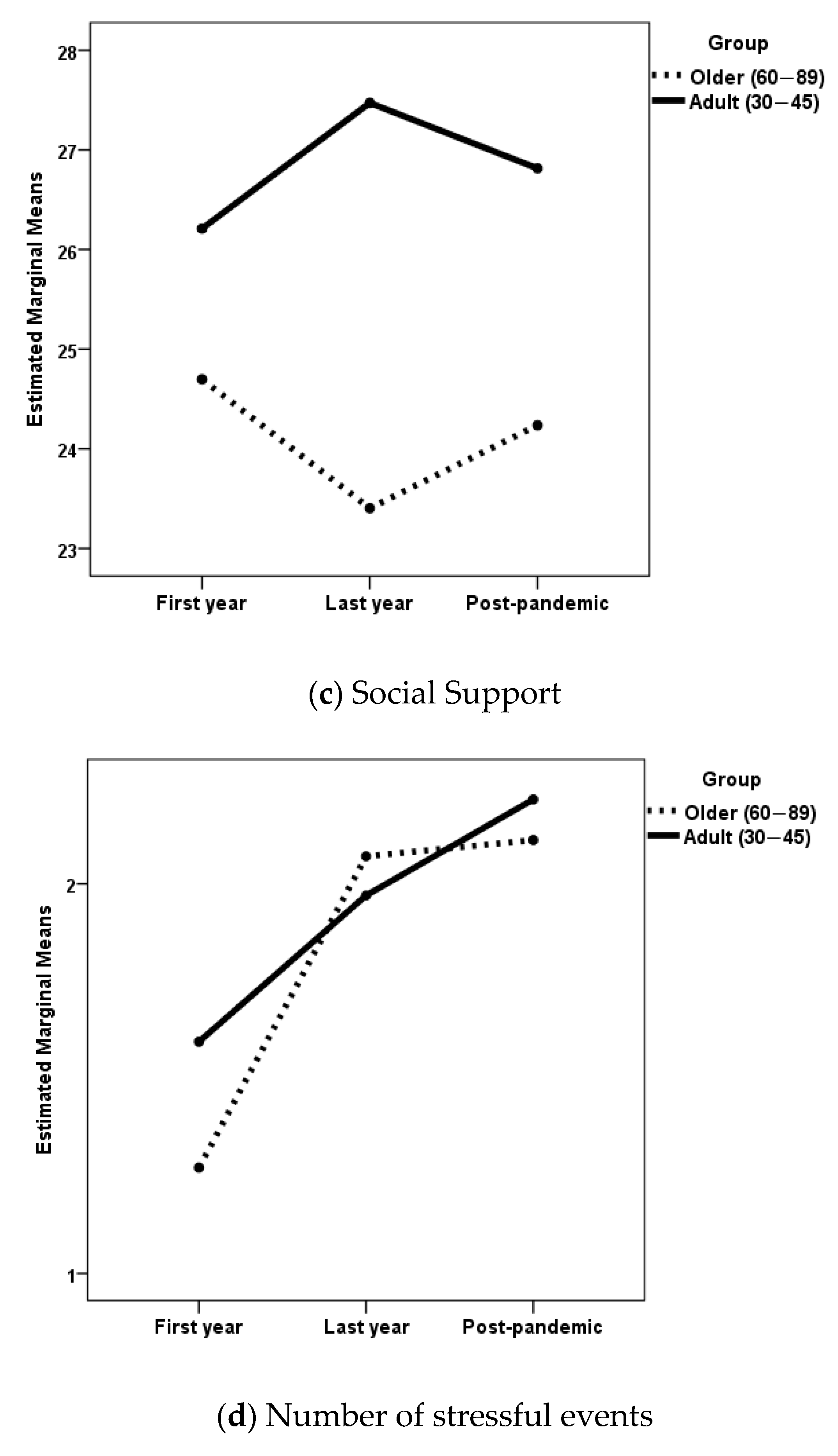

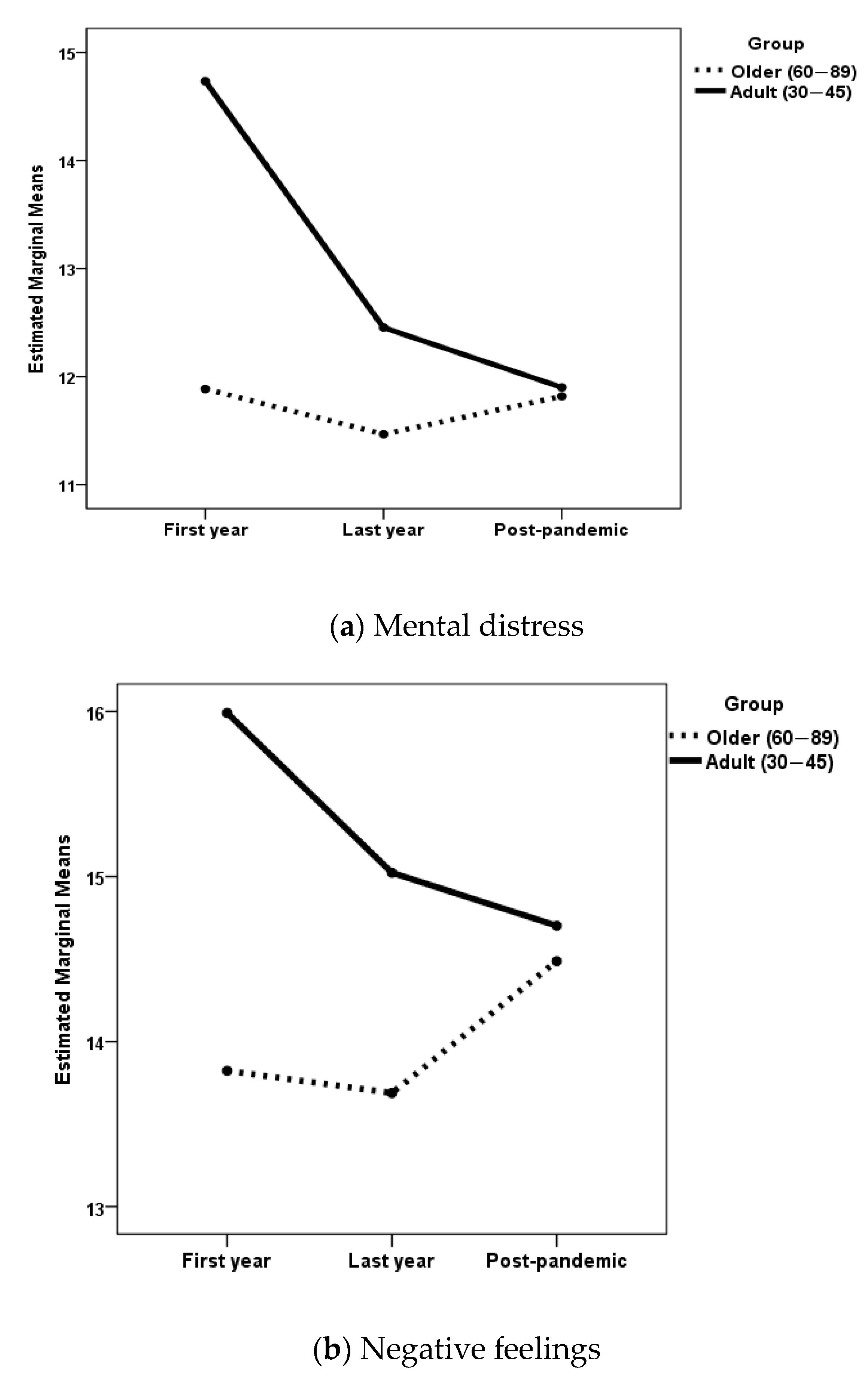

3.1. Differences in Mental Distress, Well-Being, Self-Esteem, Social Support, and Number of Stressful Events by Gender, Phase of the Pandemic, and Age Group

3.2. Predictors of Mental Distress and Well-Being in Older Women and Men in the Post-Pandemic Period

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. 2020. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- United Nations. WHO Chief Declares End to COVID-19 as a Global Health Emergency. 2023. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136367 (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Mao, Z.; Pepermans, K.; Beutels, P. Relating mental health, health-related quality of life and well-being in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional comparison in 14 European countries in early 2023. Public Health 2025, 238, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedecostante, M.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Dell’Aquila, G.; Salvi, F.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Volpato, S.; Trevisan, C.; Fumagalli, S.; Monzani, F.; Incalzi, R.A.; et al. Prediction of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in older patients using artificial intelligence: A multicenter study. Front. Aging 2024, 5, 1473632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizza, S.; Nucera, A.; Chiocchi, M.; Bellia, A.; Mereu, D.; Ferrazza, G.; Ballanti, M.; Davato, F.; Di Cola, G.; Buonomo, C.O.; et al. Metabolic characteristics in patients with COVID-19 and no-COVID-19 interstitial pneumonia with mild-to-moderate symptoms and similar radiological severity. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3227–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizza, S.; Bellia, A.; Perencin, A.; Longo, S.; Postorino, M.; Ferrazza, G.; Nucera, A.; Gervasi, R.; Lauro, D.; Federici, M. In-hospital and long-term all-cause mortality in 75 years and older hospitalized patients with and without COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 72, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Wang, C.; Crawford, T.; Holland, C. Association between COVID-19 infection and new-onset dementia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Chen, R.; Kunasekaran, M.; Honeyman, D.; Notaras, A.; Sutton, B.; Quigley, A.; MacIntyre, C.R. The risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults diagnosed with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Zhao, Y.M.; Yan, W.; Li, C.; Lu, Q.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.-Y.; Mei, H.; Yuan, K.; Shi, L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: Call for research priority and action. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admon, A.J.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Kamphuis, L.A.; Gundel, S.J.; Sahetya, S.K.; Peltan, I.D.; Chang, S.Y.; Han, J.H.; Vranas, K.C.; Mayer, K.P.; et al. Assessment of Symptom, Disability, and Financial Trajectories in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 at 6 Months. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2255795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savith, A.; Meah, A.; Murthy, R.S.; Phal, N.B. Long-term health implications of coronavirus disease 2019: A prospective study on post-coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms. Ann. Afr. Med. 2025, 24, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Yang, P.L.; Eaton, T.L.; Valley, T.S.; Langa, K.M.; Ely, E.W.; Thompson, H.J. Cognition, function, and mood post-COVID-19: Comparative analysis using the health and retirement study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.J.; Bahmer, T.; Chaplinskaya-Sobol, I.; Deckert, J.; Endres, M.; Franzpötter, K.; Geritz, J.; Haeusler, K.G.; Hein, G.; Heuschmann, P.U.; et al. Predictors of non-recovery from fatigue and cognitive deficits after COVID-19: A prospective, longitudinal, population-based study. E Clin. Med. 2024, 69, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. From Emergency Response to Long-Term COVID-19 Disease Management: Sustaining Gains Made During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 3 May 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WHE-SPP-2023.1 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Msemburi, W.; Karlinsky, A.; Knutson, V.; Aleshin-Guendel, S.; Chatterji, S.; Wakefield, J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.; Ripp, J.; Trockel, M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyah, Y.; Benjelloun, M.; Lairini, S.; Lahrichi, A. COVID-19 Impact on Public Health, Environment, Human Psychology, Global Socioeconomy, and Education. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 5578284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscott, J.; Alexandridi, M.; Muscolini, M.; Tassone, E.; Palermo, E.; Soultsioti, M.; Zevini, A. The global impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2020, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Cannot Be Made Light of. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-mental-health-cannot-be-made-light-of (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Tyagi, K.; Chaudhari, B.; Ali, T.; Chaudhury, S. Impact of COVID-19 on medical students well-being and psychological distress. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2024, 33 (Suppl. 1), S201–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020, 10, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niziurski, J.A.; Schaper, M.L. Psychological wellbeing, memories, and future thoughts during the Covid-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2422–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Losifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, L.; Gustavsson, J. Coping strategies for increased wellbeing and mental health among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—A Swedish qualitative study. Ageing Soc. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Fortuna, K.; Wister, A.; Riadi, I.; Wagner, K.; Sixsmith, A. COVID-19, Social Isolation, and Mental Health Among Older Adults: A Digital Catch-22. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donizzetti, A.R.; Capone, V. Ageism and the Pandemic: Risk and Protective Factors of Well-Being in Older People. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothan, H.A.; Byrareddy, S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isik, A.T. Covid-19 Infection in Older Adults: A Geriatrician’s Perspective. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtisalo, J.; Palmer, K.; Mangialasche, F.; Solomon, A.; Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T. Changes in Lifestyle, Behaviors, and Risk Factors for Cognitive Impairment in Older Persons During the First Wave of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in Finland: Results From the FINGER Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 624125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fristedt, S.; Carlsson, G.; Kylén, M.; Jonsson, O.; Granbom, M. Changes in daily life and wellbeing in adults, 70 years and older, in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 29, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.P.; Walters, M. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Older Adults’ Routines and Well-being: 3 Case Reports. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 10, 23337214241298326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates Bulut, E.; Kaya, D.; Aydin, A.E.; Dost, F.S.; Yildirim, A.G.; Mutlay, F.; Seydi, K.A.; Mangialasche, F.; Rocha, A.S.L.; Kivipelto, M.; et al. The psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Turkish older adults: Is there a difference between males and females? BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.A.; O’Shea, B.Q.; Eastman, M.R.; Finlay, J.M.; Kobayashi, L.C. Physical isolation and mental health among older US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal findings from the COVID-19 Coping Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Du, M.; Yue, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and subjective wellbeing among Chinese older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1425575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, L.L.; Liu, L.; Roberts, K.C.; Gariépy, G.; Capaldi, C.A. Social isolation, loneliness and positive mental health among older adults in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. Isolement social, solitude et santé mentale positive chez les aînés au Canada pendant la pandémie de COVID-19. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, R.D.; Wu, W.; Li, J.; Lawson, A.; E Bronskill, S.; A Chamberlain, S.; Grieve, J.; Gruneir, A.; Reppas-Rindlisbacher, C.; Stall, N.M.; et al. Loneliness among older adults in the community during COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in Canada. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pica, M.G.; Grullon, J.R.; Wong, R. Correlates of Loneliness and Social Isolation among Older Adults during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Comprehensive Assessment from a National United States Sample. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L.M.; Chen, C.Y. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on older adults’ mental health: Contributing factors, coping strategies, and opportunities for improvement. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37, 10.1002/gps.5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerstrom, S.C.; Crosby, P.; Witzel, D.D.; Kurth, M.L.; Choun, S.; Aldwin, C.M. Adaptation to changes in COVID-19 pandemic severity: Across older adulthood and time scales. Psychol. Aging 2023, 38, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, P.; Li, J.; Jing, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, C. Changes in psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults: The contribution of frailty transitions and multimorbidity. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, L.I.; Gedde, M.H.; Husebo, B.S.; Erdal, A.; Kjellstadli, C.; Vahia, I.V. Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress associated with the second COVID-19 wave: Prospective evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etheridge, B.; Spantig, L. The gender gap in mental well-being at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2022, 145, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothisiri, W.; Vicerra, P.M.M. Psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic in low-income and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study of older persons in Thailand. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Marzuki, A.A.; Vafa, S.; Thanaraju, A.; Yap, J.; Chan, X.W.; Harris, H.A.; Todi, K.; Schaefer, A. A systematic review on the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and emotional disorder symptoms during Covid-19: Unearthing the potential role of economic concerns and financial strain. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehm, K.E.; Brenneke, S.G.; Adams, L.B.; Gilan, D.; Lieb, K.; Kunzler, A.M.; Smail, E.J.; Holingue, C.; Stuart, E.A.; Kalb, L.G.; et al. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dones, I.; Ciobanu, R.O. Older adults’ experiences of wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative qualitative study in Italy and Switzerland. Front. Sociol. 2024, 9, 1243760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Lee, A.D.Y.; Dong, L. Psychological Wellbeing and Life Satisfaction among Chinese Older Immigrants in Canada across the Early and Late Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Ding, X.; Gan, Y.; Wang, N.; Wu, J.; Duan, H. The impact of loneliness on depression during the covid-19 pandemic in china: A two-wave follow-up study. Curr. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Zueco, J.; Díaz, A.; Del Pino, M.J.; Fortes, D. Gender differences in mental distress and affect balance during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 21790–21804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Del Pino, M.J.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Hernández-Lorenzo, D.E. Stressful Events, Psychological Distress and Well-Being during the Second Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Gender Analysis. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1291–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Panzeri, A.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Mannarini, S. The Anxiety-Buffer Hypothesis in the Time of COVID-19: When Self-Esteem Protects From the Impact of Loneliness and Fear on Anxiety and Depression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Mitra, D. COVID-19 and Americans’ Mental Health: A Persistent Crisis, Especially for Emerging Adults 18 to 29. J. Adult Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, L.S.; Friedman, J.; Spencer, C.N.; Cagney, J.; Arrieta, A.; E Herbert, M.; Stein, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Hon, J.; Patwardhan, V.; et al. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: A comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 2381–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Pimenta, D.N.; Rashid, S. Gender equality and COVID-19: Act now before it is too late. Lancet 2022, 399, 2327–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. The end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hromić-Jahjefendić, A.; Barh, D.; Uversky, V.; Aljabali, A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Alzahrani, F.M.; Alshammeri, S.; Lundstrom, K. Can COVID-19 Vaccines Induce Premature Non-Communicable Diseases: Where Are We Heading to? Vaccines 2023, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobierno de España. Ministerio de la Presidencia, Justicia y Relaciones con las Cortes. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. Orden SND/726/2023, de 4 de Julio, por la que se Publica el Acuerdo del Consejo de Ministros de 4 de Julio de 2023, por el que se Declara la Finalización de la Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada por la COVID-19. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2023-15552 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Goldberg, D.P.; Williams, P.; Lobo, A.; Muñoz, P.E. Cuestionario de Salud General GHQ (General Health Questionnaire). In Guía Para el Usuario de las Distintas Versiones; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gnambs, T.; Staufenbiel, T. The structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): Two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 2018, 12, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, A.; Åhs, J.; Åsbring, N.; Kosidou, K.; Dal, H.; Tinghög, P.; Saboonchi, F.; Dalman, C. Discriminant validity of the 12-item version of the general health questionnaire in a Swedish case-control study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2017, 71, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Zueco, J.; Del Pino-Espejo, M.J.; Fortes, D.; Beleña, M.Á.; Santos, C.; Díaz, A. The Evolution of Psychological Distress Levels in University Students in Spain during Different Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk and Protective Factors. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2583–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; del Pino, M.J.; Fortes, D.; Hernández-Lorenzo, D.E.; Ibáñez, I. Psychological distress, stressful events, and well-being in Spanish women through the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic and two years later. GHES 2024, 2, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veilleux, J.C.; Lankford, N.M.; Hill, M.A.; Skinner, K.D.; Chamberlain, K.D.; Baker, D.E.; Pollert, G.A. Affect balance predicts daily emotional experience. Pers. Indiv Dif. 2020, 154, 109683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. The development and validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2014, 6, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Vergara, J.; Aguilar-Salcedo, B.; Orihuela-Anaya, R.; Villanueva-Alvarado, J. New Psychometric Evidence of the Life Satisfaction Scale in Older Adults: An Exploratory Graph Analysis Approach. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matud, M.P. Social Support Scale [Database record]. PsycTESTS 1998. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft12441-000 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, L.A.; Schaller, M.; Park, J.H. Perceived Vulnerability to Disease: Development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2009, 47, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.; Soriano, J.F.; Beleña, Á. Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Questionnaire: Factor structure, psychometric properties and gender differences. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 101, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Díaz, A.; Pino, M.J.D.; Fortes, D.; Ibáñez, I. Gender, psychological distress, and subjective well-being two years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Cad. Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00141523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N. Gender stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalon, R.; Shnabel, N.; Becker, J.C. Positive stereotypes, negative outcomes: Reminders of the positive components of complementary gender stereotypes impair performance in counter-stereotypical tasks. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 482–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Chee, K.T.; De Deyn, M.L.Z.Q.; Chua, Z. Staying connected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Men (n = 278) | Women (n = 440) | χ2-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Education | |||||

| Primary | 63 | 22.9 | 97 | 22.1 | 9.16 * |

| Secondary | 69 | 25.1 | 72 | 16.4 | |

| University | 143 | 52.0 | 270 | 61.5 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Retired | 164 | 59.2 | 247 | 56.9 | 2.16 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 5.8 | 35 | 8.1 | |

| Working | 90 | 32.5 | 136 | 31.3 | |

| Other | 7 | 2.5 | 16 | 3.7 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Never married | 8 | 2.9 | 68 | 15.7 | 50.89 *** |

| Married/partnered | 212 | 76.8 | 228 | 52.5 | |

| Separated/divorced | 39 | 14.1 | 85 | 19.6 | |

| Widowed | 17 | 6.2 | 53 | 12.2 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | t-value | |

| Age | 66.01 | 5.77 | 65.26 | 5.14 | 1.78 |

| Number of children | 2.28 | 1.33 | 1.82 | 1.30 | 4.57 *** |

| Variable | Men | Women | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Effect | F Ratio | ηp2 | |

| Mental distress | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 11.88 | 5.82 | 14.26 | 6.52 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 11.47 | 4.58 | 13.41 | 6.11 | Gender | 11.77 *** | 0.016 |

| Post-pandemic period | 11.82 | 5.28 | 12.36 | 5.05 | Phase | 1.82 | 0.005 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 1.53 | 0.004 | ||||

| Negative feelings | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 13.82 | 4.43 | 15.45 | 4.35 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 13.69 | 3.95 | 15.12 | 4.20 | Gender | 11.24 *** | 0.016 |

| Post-pandemic period | 14.49 | 3.92 | 14.79 | 3.51 | Phase | 0.19 | 0.001 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 1.68 | 0.005 | ||||

| Positive feelings | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 20.91 | 3.74 | 20.85 | 4.22 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 21.38 | 3.98 | 21.00 | 4.29 | Gender | 0.25 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.56 | 4.09 | 21.50 | 3.45 | Phase | 1.63 | 0.005 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 0.09 | 0.000 | ||||

| Affect balance | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 7.08 | 7.17 | 5.39 | 7.76 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 7.69 | 7.10 | 5.88 | 7.39 | Gender | 4.73 * | 0.007 |

| Post-pandemic period | 7.07 | 7.43 | 6.71 | 6.22 | Phase | 0.58 | 0.002 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.63 | 0.002 | ||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 24.74 | 5.85 | 24.96 | 5.64 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 24.14 | 5.91 | 23.92 | 6.07 | Gender | 0.26 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 25.15 | 6.17 | 24.42 | 5.74 | Phase | 1.10 | 0.003 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.40 | 0.001 | ||||

| Thriving | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 37.85 | 4.76 | 37.15 | 5.74 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 36.95 | 5.40 | 37.58 | 6.06 | Gender | 0.04 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 37.88 | 5.83 | 37.67 | 5.00 | Phase | 0.38 | 0.001 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.75 | 0.002 | ||||

| Self-esteem | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 21.36 | 3.78 | 21.18 | 4.14 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 21.72 | 4.29 | 21.26 | 4.87 | Gender | 0.56 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.70 | 4.39 | 21.56 | 4.07 | Phase | 0.45 | 0.001 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.07 | 0.000 | ||||

| Social support | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 24.18 | 8.10 | 24.70 | 7.85 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 23.23 | 8.39 | 23.40 | 7.87 | Gender | 0.78 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 23.22 | 7.79 | 24.24 | 8.02 | Phase | 1.15 | 0.003 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.13 | 0.000 | ||||

| Number of stressful events | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 1.35 | 1.50 | 1.27 | 1.42 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 1.95 | 1.27 | 2.07 | 1.51 | Gender | 0.92 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 1.82 | 1.43 | 2.11 | 1.46 | Phase | 17.24 *** | 0.049 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 1.00 | 0.003 | ||||

| Variable | Men | Women | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Effect | F Ratio | ηp2 | |

| Mental distress | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 14.73 | 7.34 | 15.32 | 6.57 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 12.45 | 6.11 | 13.71 | 6.82 | Gender | 8.69 ** | 0.012 |

| Post-pandemic period | 11.90 | 5.84 | 14.82 | 7.03 | Phase | 5.98 ** | 0.017 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 1.91 | 0.005 | ||||

| Negative feelings | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 15.99 | 4.58 | 16.82 | 4.38 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 15.02 | 4.37 | 15.75 | 4.55 | Gender | 14.65 *** | 0.020 |

| Post-pandemic period | 14.70 | 4.15 | 17.22 | 4.32 | Phase | 2.78 | 0.008 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 2.71 | 0.008 | ||||

| Positive feelings | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 20.84 | 4.54 | 20.82 | 4.02 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 21.98 | 5.05 | 22.47 | 4.14 | Gender | 0.15 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 22.37 | 4.06 | 21.50 | 4.86 | Phase | 6.80 ** | 0.019 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × P | 1.15 | 0.003 | ||||

| Affect balance | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 4.85 | 8.19 | 3.99 | 7.58 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 6.95 | 8.44 | 6.71 | 7.99 | Gender | 5.57 * | 0.008 |

| Post-pandemic period | 7.67 | 7.17 | 4.28 | 8.18 | Phase | 5.47 ** | 0.015 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 2.23 | 0.006 | ||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 24.26 | 7.05 | 23.90 | 6.55 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 25.46 | 6.67 | 24.35 | 6.61 | Gender | 4.31 * | 0.006 |

| Post-pandemic period | 25.39 | 6.41 | 23.45 | 7.39 | Phase | 0.77 | 0.002 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.85 | 0.002 | ||||

| Thriving | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 37.34 | 7.26 | 37.47 | 6.40 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 39.26 | 6.83 | 39.01 | 6.75 | Gender | 0.38 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 38.73 | 7.09 | 37.84 | 7.02 | Phase | 3.42 * | 0.010 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.34 | 0.001 | ||||

| Self-esteem | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 20.92 | 4.76 | 20.98 | 4.95 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 21.93 | 5.51 | 21.52 | 5.26 | Gender | 0.57 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.25 | 4.93 | 20.65 | 5.94 | Phase | 1.32 | 0.004 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.27 | 0.001 | ||||

| Social support | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 24.25 | 9.04 | 26.21 | 8.46 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 26.12 | 8.13 | 27.47 | 8.72 | Gender | 3.72 | 0.005 |

| Post-pandemic period | 26.15 | 8.57 | 26.81 | 7.68 | Phase | 2.27 | 0.006 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 0.36 | 0.001 | ||||

| Number of stressful events | |||||||

| First year of the pandemic | 1.83 | 1.59 | 1.59 | 1.45 | |||

| Last pandemic year | 1.95 | 1.51 | 1.97 | 1.66 | Gender | 0.28 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 1.81 | 1.45 | 2.22 | 1.56 | Phase | 2.72 | 0.008 |

| Gender × Phase interaction | G × Phase | 2.65 | 0.008 | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.32 | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| Number of children | −0.05 | −0.40 | −0.10 | −0.91 | −0.10 | −0.99 | −0.07 | −0.69 | −0.05 | −0.56 |

| Education | −0.11 | −0.93 | −0.05 | −0.49 | −0.07 | −0.78 | −0.08 | −0.85 | −0.11 | −1.22 |

| Married/partnered | −0.05 | −0.49 | −0.09 | −0.92 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.39 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.50 | 5.27 *** | 0.36 | 3.91 *** | 0.32 | 3.64 *** | 0.29 | 3.31 ** | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.38 | 4.11 *** | 0.34 | 3.90 *** | 0.30 | 3.36 ** | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.30 | 3.62 *** | −0.24 | −2.85 ** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.12 | −1.28 | ||||||||

| Social support | −0.16 | −1.72 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.51 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.46 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.02 | 0.24 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.05 * | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Age | −0.26 | −2.45 * | −0.25 | −2.44* | −0.26 | −2.86 ** | −0.27 | −3.15 ** | −0.21 | −2.68 ** |

| Number of children | 0.14 | 1.21 | 0.13 | 1.15 | 0.12 | 1.19 | 0.14 | 1.49 | 0.08 | 0.91 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.00 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| Married/partnered | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.19 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.21 | 2.19* | 0.16 | 1.82 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.26 | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.42 | 4.78 *** | 0.35 | 4.14 *** | 0.33 | 4.15 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.36 | −3.88 *** | −0.20 | −2.14 * | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.33 | −3.63 *** | ||||||||

| Social support | −0.10 | −1.18 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.50 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.45 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.06 | 0.05* | 0.18 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.11 *** | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Age | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 1.50 |

| Number of children | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.36 | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.42 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.03 | −0.28 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.77 |

| Married/partnered | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.26 | −0.00 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.32 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | −0.35 | −3.43 ** | −0.24 | −2.27 * | −0.18 | −1.86 | −0.10 | −1.35 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.32 | −3.08 ** | −0.27 | −2.81 ** | −0.16 | −2.01 * | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.42 | 4.67 *** | 0.28 | 3.73 *** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.29 | 3.40 ** | ||||||||

| Social support | 0.34 | 4.10 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.61 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.57 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.01 | 0.12 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.16 *** | 0.23 *** | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Number of children | −0.08 | −0.73 | −0.08 | −0.69 | −0.07 | −0.67 | −0.10 | −1.01 | 0.02 | 0.24 |

| Education | −0.11 | −0.99 | −0.11 | −0.95 | −0.14 | −1.28 | −0.17 | −1.74 | −0.10 | −1.46 |

| Married/partnered | −0.02 | −0.22 | −0.03 | −0.25 | −0.00 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.53 | −0.01 | −0.18 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | −0.10 | −0.96 | −0.05 | −0.54 | 0.12 | 1.32 | 0.13 | 1.95 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.38 | −3.91 *** | −0.28 | −3.18 ** | −0.24 | −3.81 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.46 | 4.81 *** | 0.20 | 2.67 ** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.51 | 6.80 *** | ||||||||

| Social support | 0.25 | 3.68 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.66 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.63 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.33 *** | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matud, M.P. COVID-19 and Mental Distress and Well-Being Among Older People: A Gender Analysis in the First and Last Year of the Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10010005

Matud MP. COVID-19 and Mental Distress and Well-Being Among Older People: A Gender Analysis in the First and Last Year of the Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatud, M. Pilar. 2025. "COVID-19 and Mental Distress and Well-Being Among Older People: A Gender Analysis in the First and Last Year of the Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period" Geriatrics 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10010005

APA StyleMatud, M. P. (2025). COVID-19 and Mental Distress and Well-Being Among Older People: A Gender Analysis in the First and Last Year of the Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period. Geriatrics, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10010005