Voice-Based Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine and Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Databases Used

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

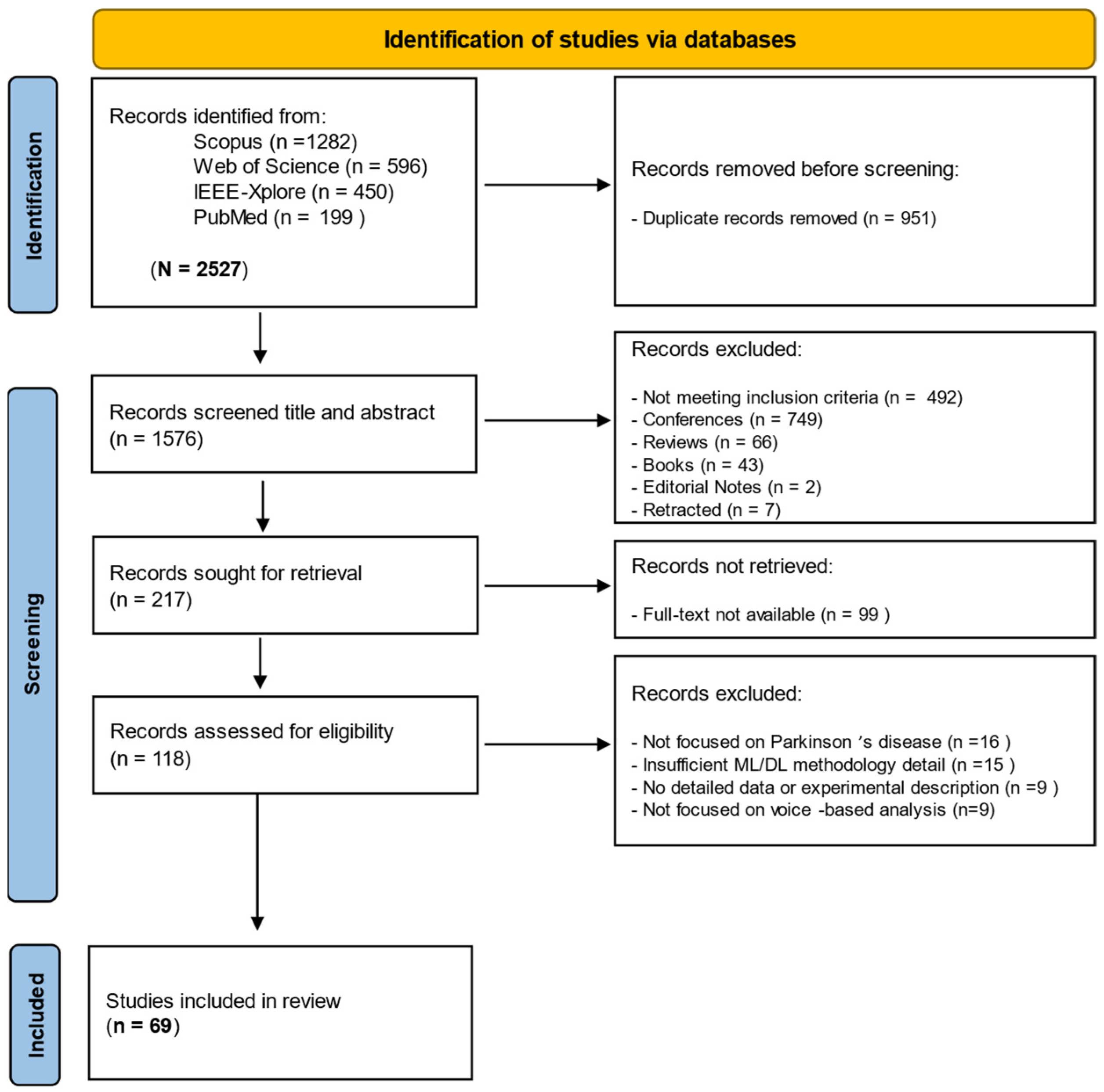

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

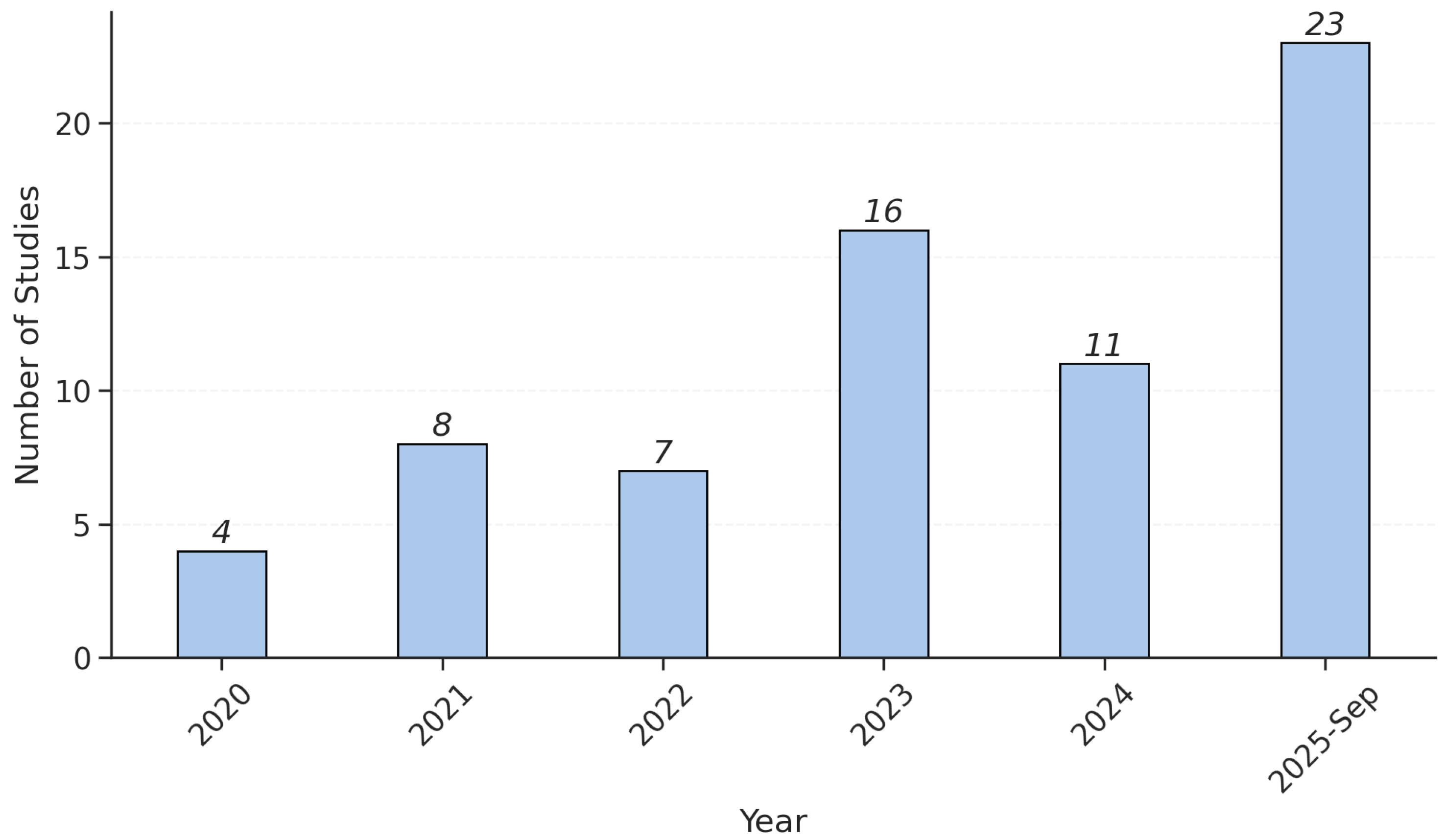

3. Results

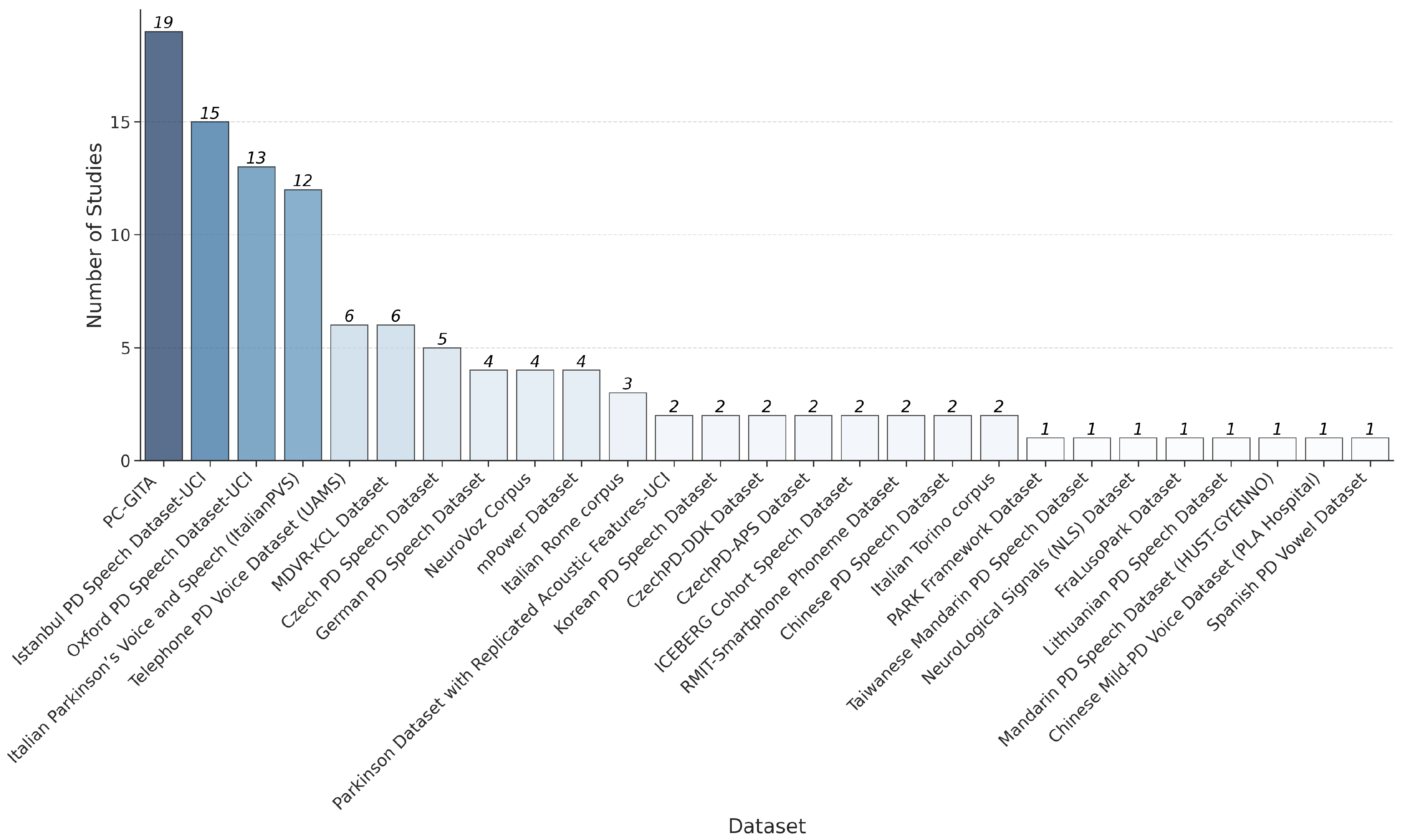

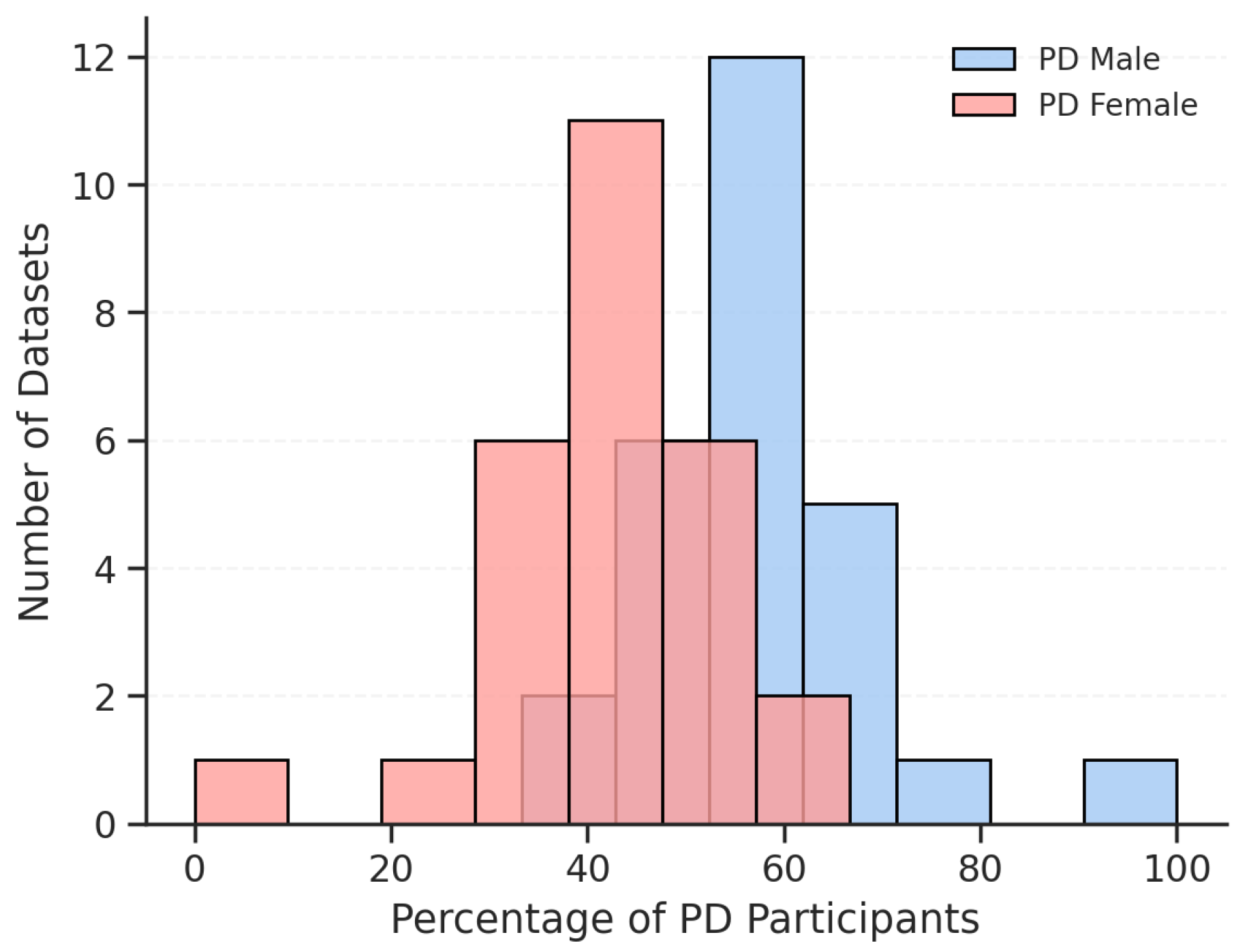

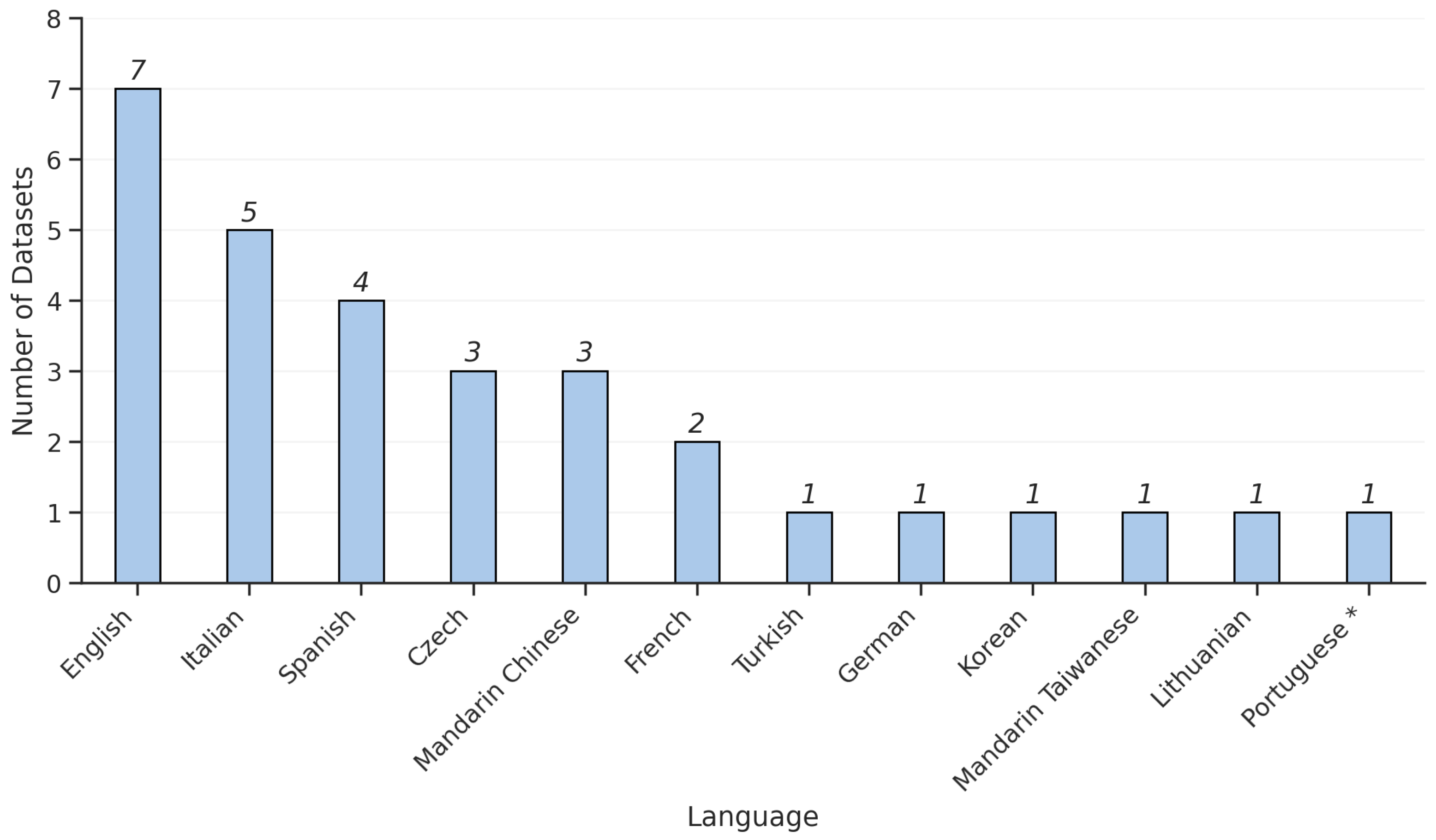

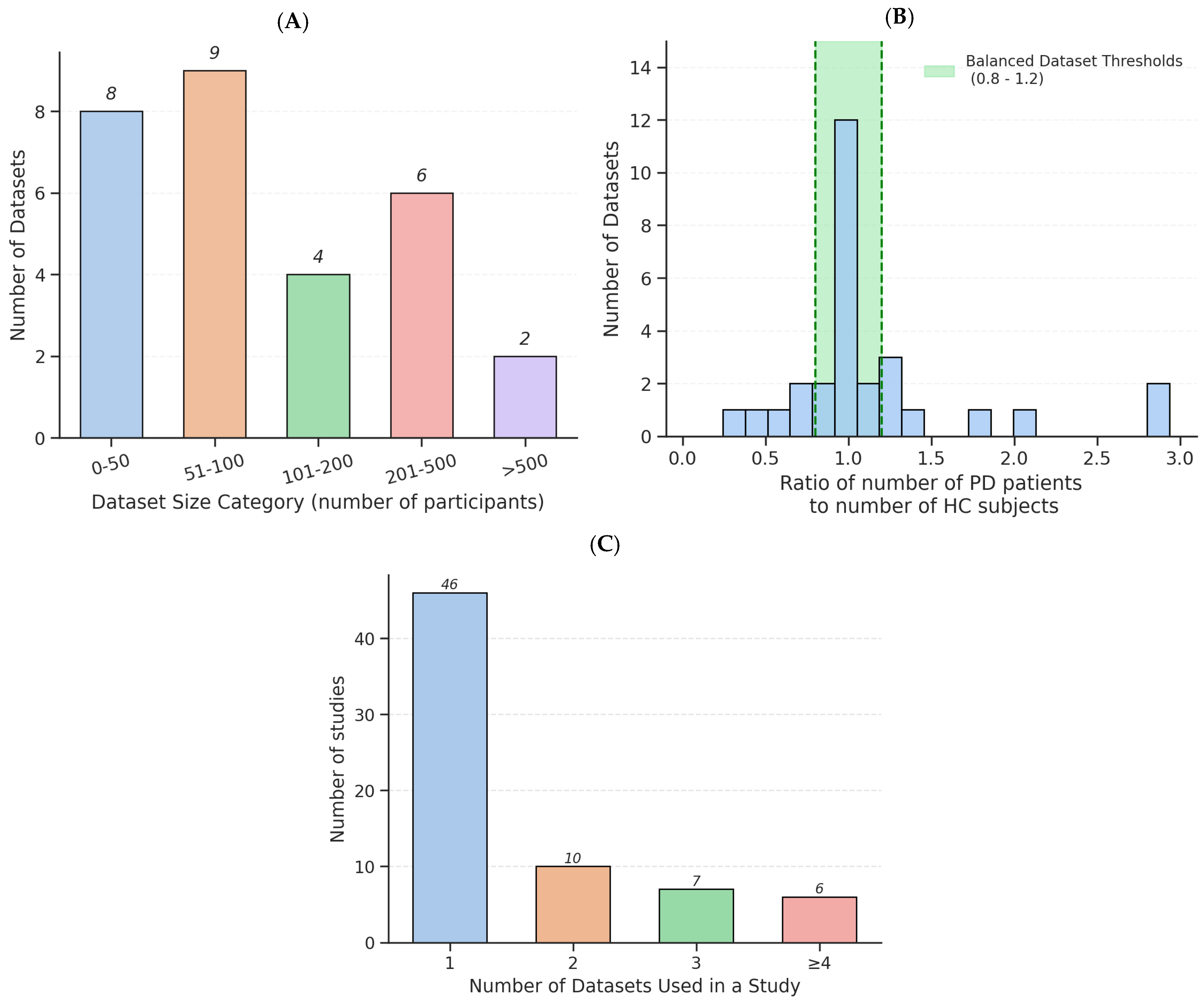

3.1. Dataset Characteristics

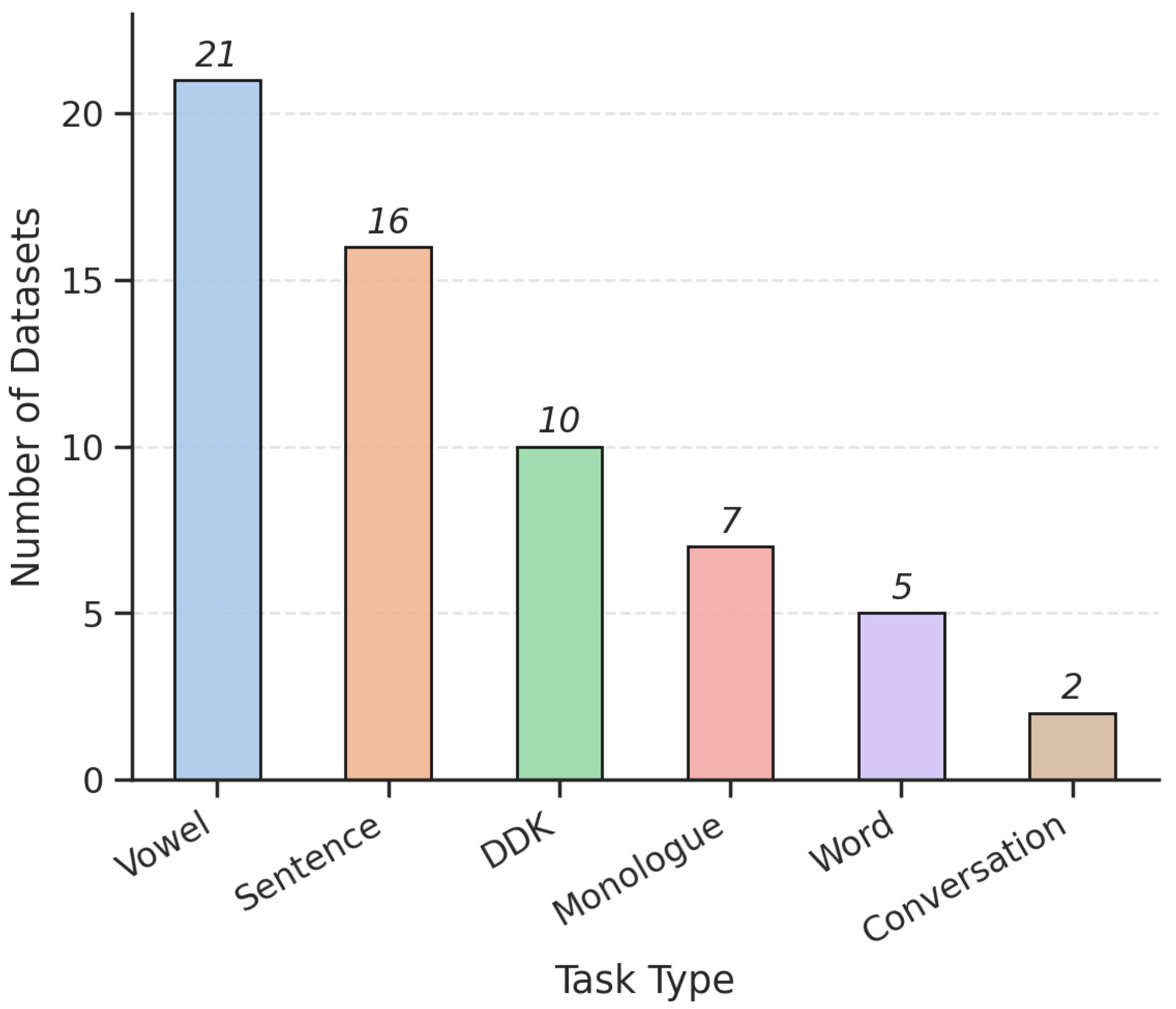

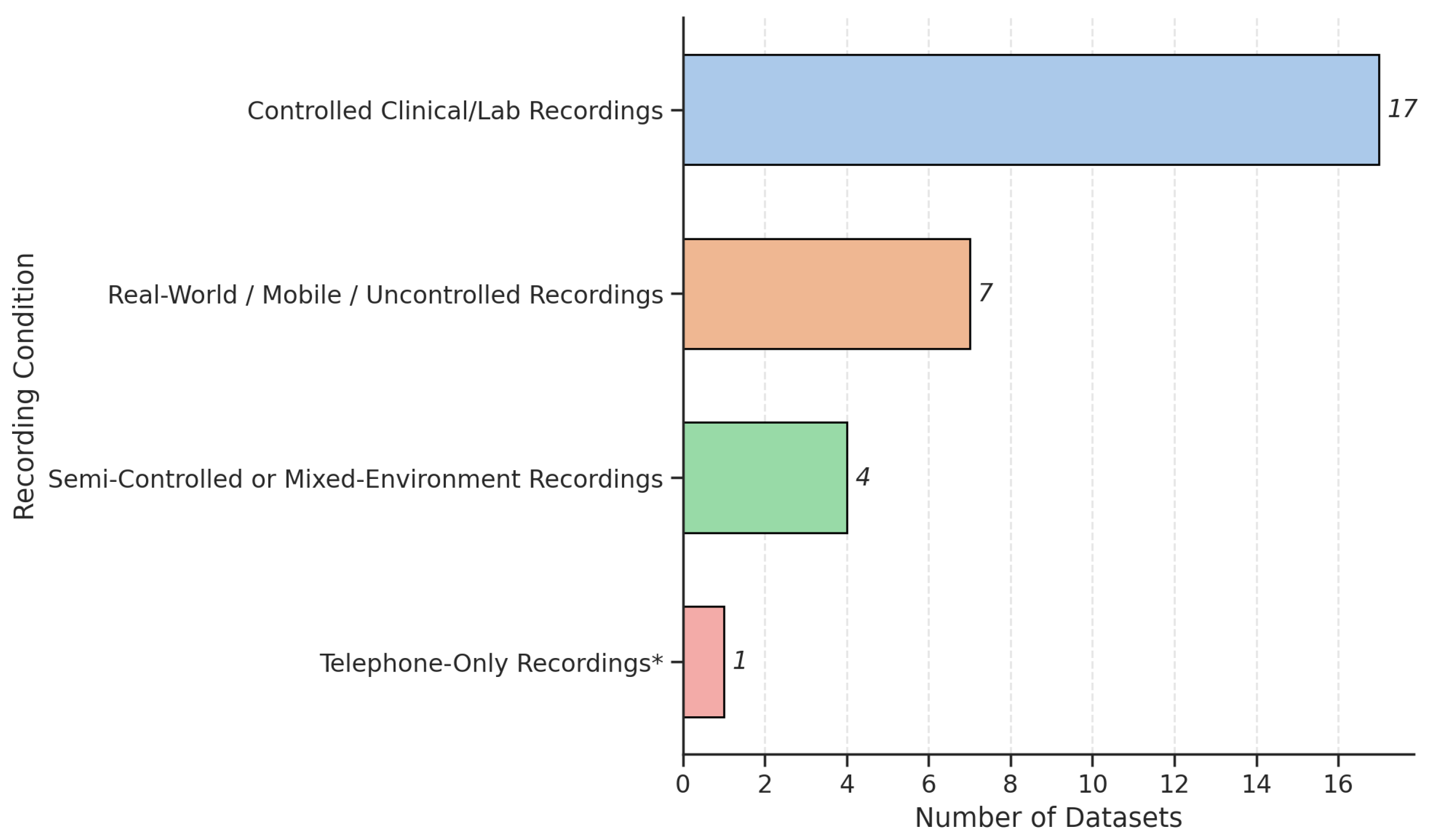

3.2. Voice Tasks and Recording Protocols

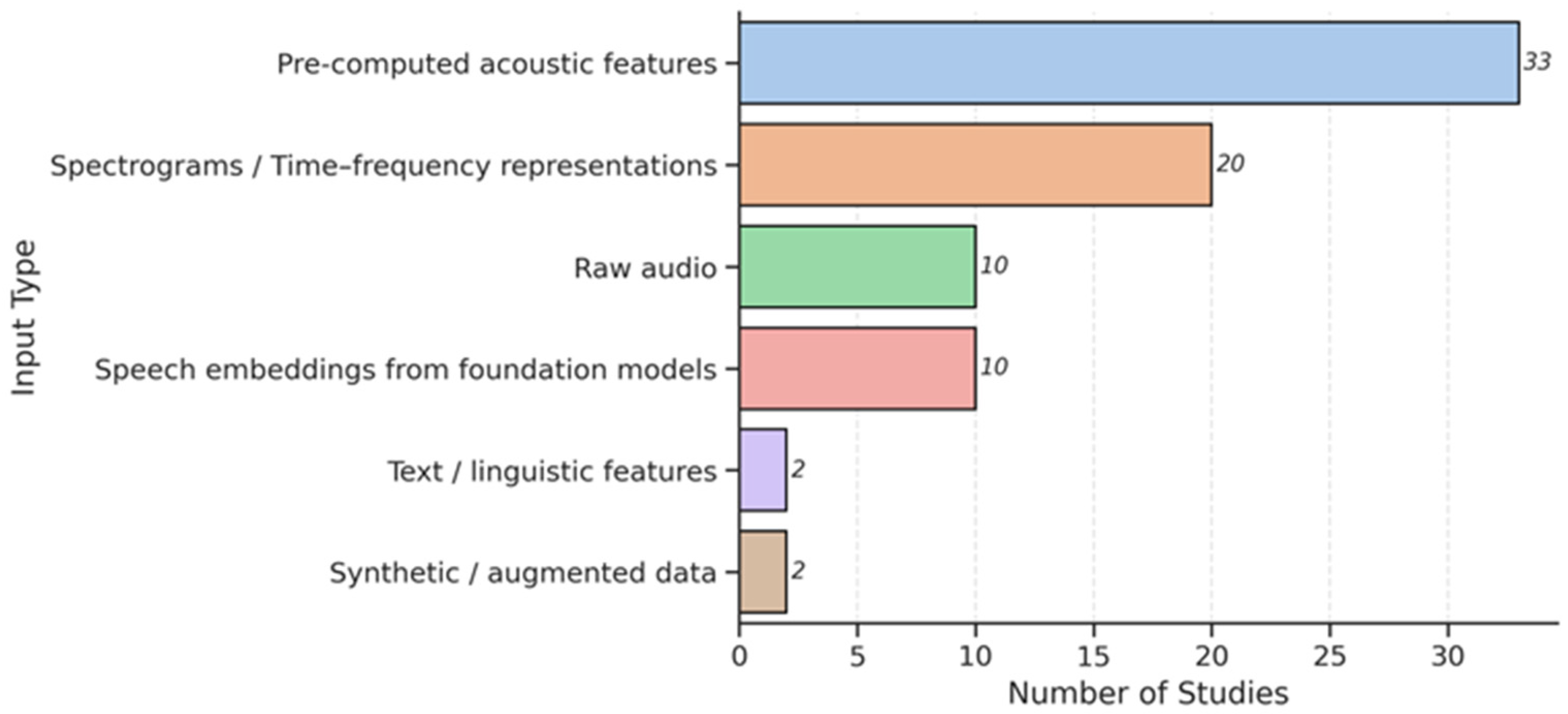

3.3. Feature Extraction and Input Data

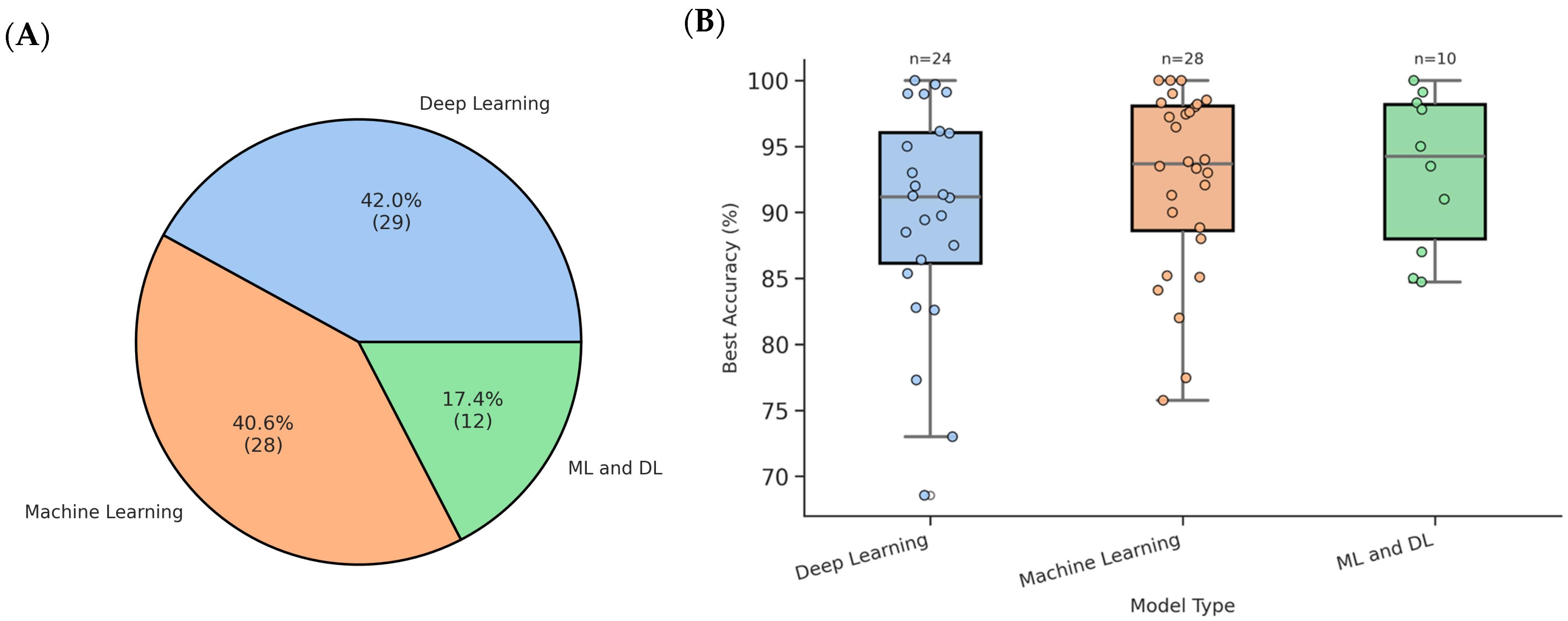

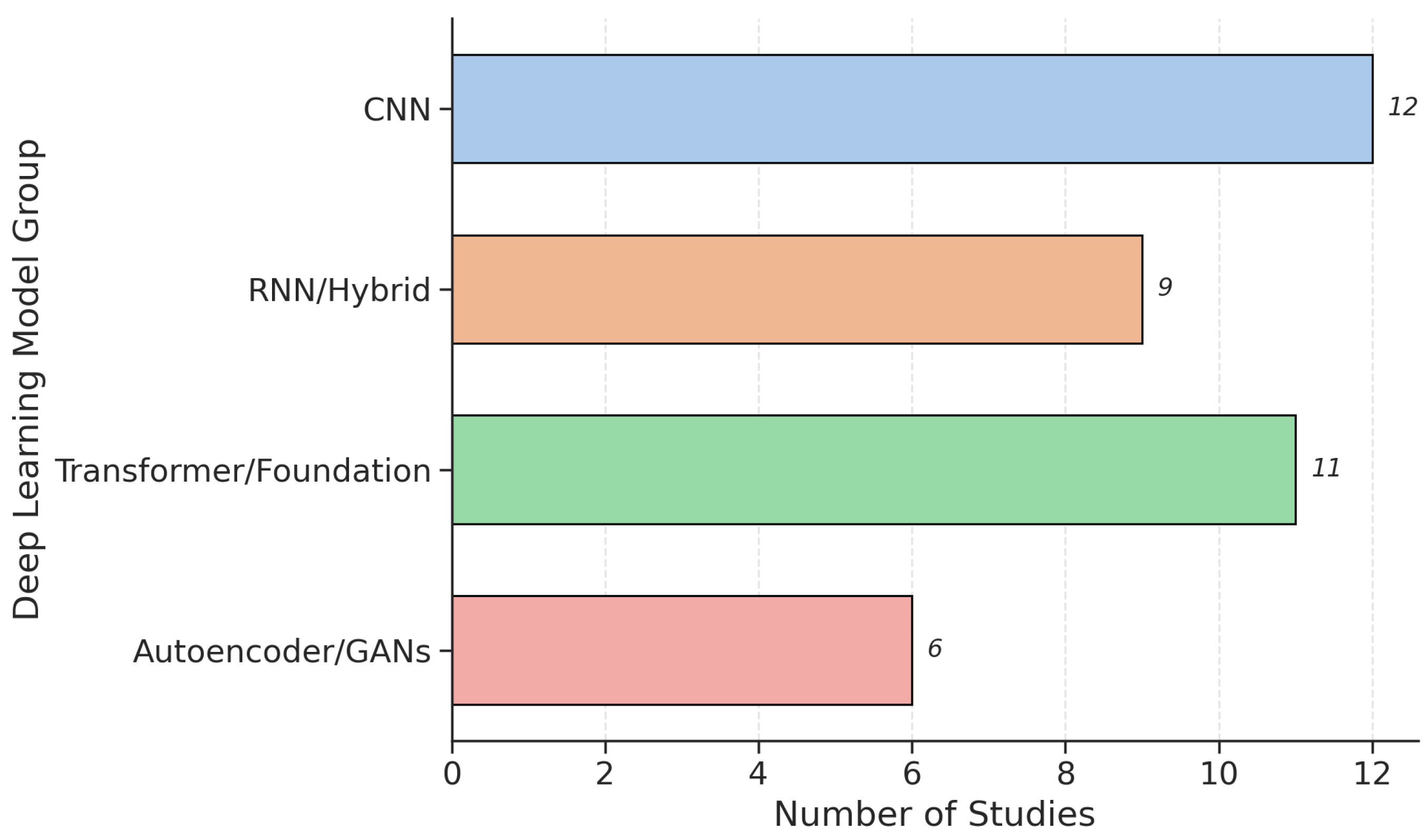

3.4. Machine-Learning and Deep-Learning Models

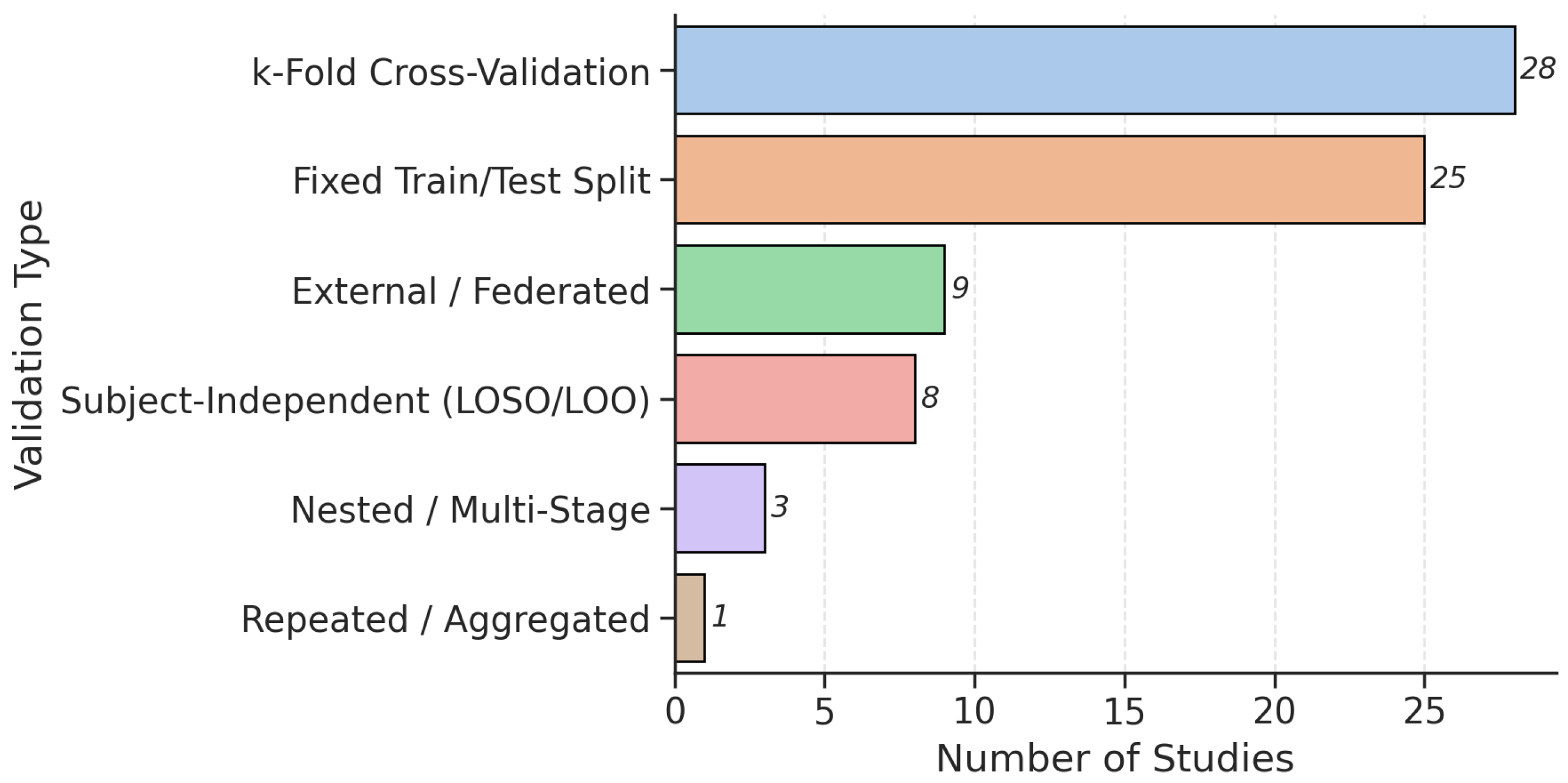

3.5. Model Validations

4. Discussion

4.1. Dataset Design, Recording Variability, and Accessibility

4.2. Advancements in Machine Learning

4.3. Methodological and Reporting Limitations

4.4. Limitations of the Current Review

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| AST | Audio Spectrogram Transformer |

| AUC/AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| DDK | Diadochokinetic |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| HC | Healthy Control |

| HNR | Harmonics-to-Noise Ratio |

| H&Y | Hoehn & Yahr scale |

| KNN (k-NN) | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LOOCV | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| LOSO | Leave-One-Subject-Out |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MFCCs | Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RFE | Recursive Feature Elimination |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SLT | Superlet Transform |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| UPDRS/MDS-UPDRS | (Movement Disorder Society)-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| Wav2Vec 2.0 | Self-supervised speech model developed by Facebook AI |

References

- Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Nichols, E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Adsuar, J.C.; Ansha, M.G.; Brayne, C.; Choi, J.-Y.J.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Parkinson’s Disease, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Batzu, L.; Halliday, G.; Geurtsen, G.; Ballard, C.; Chaudhuri, R.; Weintraub, D. Parkinson Disease-Associated Cognitive Impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Desrosiers, C.; Frasnelli, J. Machine Learning for the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of Literature. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 633752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.A.; Chakravarthy, S.; Phillips, J.R.; Gupta, A.; Keri, S.; Polner, B.; Frank, M.J.; Jahanshahi, M. Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: A Unified Framework. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, J.A.; Chand, P.; Anch, A.M. Multifactorial Sleep Disturbance in Parkinson’s Disease. Sleep Med. 2017, 35, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, C.; Beck, J.; Bower, J.; Roberts, E.; Ritz, B.; Ross, G.; Abbott, R.; Savica, R.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Willis, A.; et al. Prevalence of Parkinson’s Disease across North America. npj Park. Dis. 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Cui, Y.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bai, R.; Zhu, J.; Lam, J.S.T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Zheng, X.; et al. Projections for Prevalence of Parkinson’s Disease and Its Driving Factors in 195 Countries and Territories to 2050: Modelling Study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale Presentation and Clinimetric Testing Results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; Sampaio, C.; Stebbins, G.T.; Counsell, C.; Giladi, N.; Holloway, R.G.; Moore, C.G.; Wenning, G.K.; et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force Report on the Hoehn and Yahr Staging Scale: Status and Recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawi, S.; Alhozami, J.; AlQahtani, R.; AlSafran, D.; Alqarni, M.; Sahmarany, L.E. Automatic Parkinson’s Disease Detection Based on the Combination of Long-Term Acoustic Features and Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC). Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 78, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeancolas, L.; Petrovska-Delacrétaz, D.; Mangone, G.; Benkelfat, B.-E.; Corvol, J.-C.; Vidailhet, M.; Lehéricy, S.; Benali, H. X-Vectors: New Quantitative Biomarkers for Early Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Speech. Front. Neuroinform. 2021, 15, 578369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiang, J.; Wu, F.-X.; Li, M. A Dual Ranking Algorithm Based on the Multiplex Network for Heterogeneous Complex Disease Analysis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angelis, O.; Di Biase, L.; Vollero, L.; Merone, M. IoT Architecture for Continuous Long Term Monitoring: Parkinson’s Disease Case Study. Internet Things 2022, 20, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundas, A.; Badotra, S.; Shahi, G.S.; Verma, A.; Bharany, S.; Ibrahim, A.O.; Abulfaraj, A.W.; Binzagr, F. Smart Patient Monitoring and Recommendation (SPMR) Using Cloud Analytics and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 54238–54255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, A.A.; Awokola, J.A.; Alam, S.; Bharany, S.; Agboola, P.; Shuaib, M.; Ahmed, R. A Hybrid Framework of Blockchain and IoT Technology in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Comprehensive Study. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2023, 2023, 3265310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Bohre, K.; Singh, Y.; Himeur, Y.; Mansoor, W.; Atalla, S.; Srinivasan, K. A Comprehensive Review on AI-Enabled Models for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis. Electronics 2023, 12, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Chen, Z.; Ren, K.; Luo, Z. FedOcw: Optimized Federated Learning for Cross-Lingual Speech-Based Parkinson’s Disease Detection. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.G.; Mehralian, P.; Naseri, A.; Sajedi, H. Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis: The Effect of Autoencoders on Extracting Features from Vocal Characteristics. Array 2021, 11, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Vogel, A.P.; Gharahkhani, P.; Renteria, M.E. Speech and Language Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease Prediction, Early Diagnosis and Progression. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair-Ouellet, N.; Lieberman, P.; Monchi, O. Contribution of Language Studies to the Understanding of Cognitive Impairment and Its Progression over Time in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Du, F.; Yang, Y. MLM-EOE: Automatic Depression Detection via Sentimental Annotation and Multi-Expert Ensemble. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2025, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Chetty, M.; Noori Hoshyar, A.; Bhattacharya, T.; Klein, B. Speech Based Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Survey of AI Techniques, Datasets and Challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Karjadi, C.; Paschalidis, I.C.; Au, R.; Kolachalama, V.B. Detection of Dementia on Voice Recordings Using Deep Learning: A Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimer′s Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y. Automatic Depression Recognition with an Ensemble of Multimodal Spatio-Temporal Routing Features. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2025, 16, 1855–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Shao, B.; Chang, L.; Ren, K.; Chen, Z.; Ling, Y. Early Detection of Parkinson’s Disease from Multiple Signal Speech: Based on Mandarin Language Dataset. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1036588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motin, M.A.; Pah, N.D.; Raghav, S.; Kumar, D.K. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Smartphone Recorded Phonemes in Real World Conditions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 97600–97609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabayir, I.; Goldman, S.M.; Pappu, S.; Akbilgic, O. Gradient Boosting for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis from Voice Recordings. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Amenta, F. Machine Learning-Based Classification of Parkinson’s Disease Patients Using Speech Biomarkers. J. Park. Dis. 2023, 14, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra, E.J.; Arias-Londoño, J.D.; Zañartu, M.; Godino-Llorente, J.I. Towards a Corpus (and Language)-Independent Screening of Parkinson’s Disease from Voice and Speech through Domain Adaptation. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, A.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Butala, A.; Thebaud, T.; Villalba, J.; Dehak, N.; Moro-Velázquez, L. Interpretable Speech Features vs. DNN Embeddings: What to Use in the Automatic Assessment of Parkinson’s Disease in Multi-Lingual Scenarios. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 166, 107559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, I.; Ditta, A.; Mazhar, T.; Anwar, M.; Saeed, M.M.; Hamam, H. Voice Biomarkers as Prognostic Indicators for Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hireš, M.; Gazda, M.; Drotár, P.; Pah, N.D.; Motin, M.A.; Kumar, D.K. Convolutional Neural Network Ensemble for Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Voice Recordings. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Ren, K.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ling, Y. End-to-End Deep Learning Approach for Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Speech Signals. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 42, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarmathi, P.; Suganya, Y.; Saranya, K.R.; Shanmuga Priya, S. Enhancing Parkinson Disease Detection through Feature Based Deep Learning with Autoencoders and Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno-Gómez, D.; Botelho, C.; Pompili, A.; Abad, A.; Martínez-Hinarejos, C.-D. Unveiling Interpretability in Self-Supervised Speech Representations for Parkinson’s Diagnosis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, Q.; Jeancolas, L.; Mangone, G.; Sambin, S.; Chalançon, A.; Gomes, M.; Lehéricy, S.; Corvol, J.-C.; Vidailhet, M.; Arnulf, I.; et al. Detection of Early Parkinson’s Disease by Leveraging Speech Foundation Models. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 5181–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Q.C.; Motin, M.A.; Pah, N.D.; Drotár, P.; Kempster, P.; Kumar, D. Computerized Analysis of Speech and Voice for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 226, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, H.; Akhloufi, M.A. A Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altham, C.; Zhang, H.; Pereira, E. Machine Learning for the Detection and Diagnosis of Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco-Arroyave, J.R.; Arias-Londoño, J.D.; Vargas-Bonilla, J.F.; González-Rátiva, M.C.; Nöth, E. New Spanish Speech Corpus Database for the Analysis of People Suffering from Parkinson’s Disease. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–31 May 2014; Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Loftsson, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Reykjavik, Iceland, 2014; pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Sakar, B.E.; Isenkul, M.E.; Sakar, C.O.; Sertbas, A.; Gurgen, F.; Delil, S.; Apaydin, H.; Kursun, O. Collection and Analysis of a Parkinson Speech Dataset with Multiple Types of Sound Recordings. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2013, 17, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M.A.; McSharry, P.E.; Roberts, S.J.; Costello, D.A.; Moroz, I.M. Exploiting Nonlinear Recurrence and Fractal Scaling Properties for Voice Disorder Detection. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2007, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimauro, G.; Di Nicola, V.; Bevilacqua, V.; Caivano, D.; Girardi, F. Assessment of Speech Intelligibility in Parkinson’s Disease Using a Speech-To-Text System. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 22199–22208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimauro, G.; Caivano, D.; Bevilacqua, V.; Girardi, F.; Napoletano, V. VoxTester, Software for Digital Evaluation of Speech Changes in Parkinson Disease. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Benevento, Italy, 15–18 May 2016; IEEE Press: Benevento, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Virmani, T.; Lotia, M.; Glover, A.; Pillai, L.; Kemp, A.S.; Iyer, A.; Farmer, P.; Syed, S.; Larson-Prior, L.J.; Prior, F.W. Feasibility of Telemedicine Research Visits in People with Parkinson’s Disease Residing in Medically Underserved Areas. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 6, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, H.; Trivedi, D.; Stadtschnitzer, M. Mobile Device Voice Recordings at King’s College London (MDVR-KCL) from Both Early and Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Patients and Healthy Controls; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tsanas, A.; Little, M.A.; McSharry, P.E.; Ramig, L.O. Accurate Telemonitoring of Parkinson’s Disease Progression by Noninvasive Speech Tests. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Borzi, L.; Olmo, G.; Artusi, C.A.; Imbalzano, G.; Lopiano, L. Speech Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease: Acoustic Analysis of Unvoiced Consonants in Italian Native Speakers. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 166370–166381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scimeca, S.; Amato, F.; Olmo, G.; Asci, F.; Suppa, A.; Costantini, G.; Saggio, G. Robust and Language-Independent Acoustic Features in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1198058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocklet, T.; Steidl, S.; Nöth, E.; Skodda, S. Automatic Evaluation of Parkinson’s Speech—Acoustic, Prosodic and Voice Related Cues. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2013, Lyon, France, 25–29 August 2013; ISCA: Singapore, 2013; pp. 1149–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Rusz, J.; Cmejla, R.; Tykalova, T.; Ruzickova, H.; Klempir, J.; Majerova, V.; Picmausova, J.; Roth, J.; Ruzicka, E. Imprecise Vowel Articulation as a Potential Early Marker of Parkinson’s Disease: Effect of Speaking Task. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Laureano, J.; Gómez-García, J.A.; Guerrero-López, A.; Luque-Buzo, E.; Arias-Londoño, J.D.; Grandas-Pérez, F.J.; Godino-Llorente, J.I. NeuroVoz: A Castillian Spanish Corpus of Parkinsonian Speech. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, S.; Cardoso, R.; Sadat, J.; Guimarães, I.; Mercier, C.; Santos, H.; Atkinson-Clement, C.; Carvalho, J.; Welby, P.; Oliveira, P.; et al. Dysarthria in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Protocol for a Binational, Cross-Sectional, Case-Controlled Study in French and European Portuguese (FraLusoPark). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmatallah, Y.; Kemp, A.S.; Iyer, A.; Pillai, L.; Larson-Prior, L.J.; Virmani, T.; Prior, F. Pre-Trained Convolutional Neural Networks Identify Parkinson’s Disease from Spectrogram Images of Voice Samples. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, T.; Abdelkader, A.; Liu, Z.; Hossain, E.; Park, S.; Islam, M.S.; Hoque, E. A Novel Fusion Architecture for Detecting Parkinson’s Disease Using Semi-Supervised Speech Embeddings. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bot, B.M.; Suver, C.; Neto, E.C.; Kellen, M.; Klein, A.; Bare, C.; Doerr, M.; Pratap, A.; Wilbanks, J.; Dorsey, E.R.; et al. The mPower Study, Parkinson Disease Mobile Data Collected Using ResearchKit. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.S.; Chiu, S.-I.; Peng, P.-L.; Jang, J.-S.R.; Lee, S.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Kim, H.-J. A Cross-Language Speech Model for Detection of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neural Transm. 2024, 132, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.-M.; Song, Y.-D.; Seok, C.-L.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, E.C.; Kim, H.-J. Machine Learning-Based Classification of Parkinson’s Disease Using Acoustic Features: Insights from Multilingual Speech Tasks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 182, 109078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Tang, R.; Yao, J.; Lin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Ling, Y.; et al. Using Sustained Vowels to Identify Patients with Mild Parkinson’s Disease in a Chinese Dataset. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1377442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, L.; Pérez, C.J.; Martín, J. Addressing Voice Recording Replications for Tracking Parkinson’s Disease Progression. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 55, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempíř, O.; Příhoda, D.; Krupička, R. Evaluating the Performance of Wav2vec Embedding for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2023, 23, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavnička, J.; Čmejla, R.; Klempíř, J.; Růžička, E.; Rusz, J. Acoustic Tracking of Pitch, Modal, and Subharmonic Vibrations of Vocal Folds in Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 150339–150354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiciukynas, E.; Verikas, A.; Gelzinis, A.; Bacauskiene, M. Detecting Parkinson’s Disease from Sustained Phonation and Speech Signals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R.; Khojasteh, P.; Aliahmad, B.; Arjunan, S.P.; Ragnav, S.; Kempster, P.; Wong, K.; Nagao, J.; Kumar, D.K. Efficiency of Voice Features Based on Consonant for Detection of Parkinson’s Disease. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Life Sciences Conference (LSC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 28–30 October 2018; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Suppa, A.; Costantini, G.; Asci, F.; Di Leo, P.; Al-Wardat, M.S.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Scalise, S.; Pisani, A.; Saggio, G. Voice in Parkinson’s Disease: A Machine Learning Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 831428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, M.; Fernandez, L.; Pérez, S. Selección de Medidas de Disfonía Para La Identificación de Enfermos de Parkinson [Not Available in English]. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Congreso Bienal de Argentina (ARGENCON), Resistencia, Argentina, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Momeni, N.; Whitling, S.; Jakobsson, A. Interpretable Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Group-Wise Scaling. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29147–29161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, S.; Mus, L.; Blandini, F. Parkinson’s Disease in Women and Men: What’s the Difference? J. Park. Dis. 2019, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, D.; Georgiev, D.; Hamberg, K.; Hariz, M.; Hariz, M.; Forsgren, L.; Hariz, G. Gender Differences in Parkinson’s Disease: A Clinical Perspective. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017, 136, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P.; Weenink, D. PRAAT, a System for Doing Phonetics by Computer. Glot Int. 2001, 5, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Eyben, F.; Weninger, F.; Groß, F.; Schuller, B. Recent Developments in openSMILE, the Munich Open-Source Multimedia Feature Extractor. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Brisbane, Australia, 23–27 October 2013; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2502081.2502224 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Vásquez-Correa, J.C.; Fritsch, J.; Orozco-Arroyave, J.R.; Nöth, E.; Magimai-Doss, M. On Modeling Glottal Source Information for Phonation Assessment in Parkinson′s Disease. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2021, Brno, Czechia, 30 August–3 September 2021; ISCA: Singapore, 2021; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, H.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. Wav2vec 2.0: A Framework for Self-Supervised Learning of Speech Representations. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 12449–12460. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.-N.; Bolte, B.; Tsai, Y.-H.H.; Lakhotia, K.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Mohamed, A. HuBERT: Self-Supervised Speech Representation Learning by Masked Prediction of Hidden Units. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; JMLR.org: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2023; Volume 202, pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Kanda, N.; Yoshioka, T.; Xiao, X.; et al. WavLM: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pre-Training for Full Stack Speech Processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-J.; Wang, R.-F.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.-H. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Based on Spectrogram-Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network Sample Augmentation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 206888–206900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Paredes, M.; Pérez, C.J.; Mateos-Caballero, A. Time Series Classification of Raw Voice Waveforms for Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Generative Adversarial Network-Driven Data Augmentation. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Grisales, D.; Ríos-Urrego, C.D.; Orozco-Arroyave, J.R. Deep Learning and Artificial Intelligence Applied to Model Speech and Language in Parkinson’s Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougui, I.; Zakroum, M.; Karrakchou, O.; Ghogho, M. Transformer-Based Transfer Learning on Self-Reported Voice Recordings for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedigh Malekroodi, H.; Madusanka, N.; Lee, B.; Yi, M. Speech-Based Parkinson’s Detection Using Pre-Trained Self-Supervised Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) Models and Supervised Contrastive Learning. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempir, O.; Skryjova, A.; Tichopad, A.; Krupicka, R. Ranking Pre-Trained Speech Embeddings in Parkinson’s Disease Detection: Does Wav2Vec 2.0 Outperform Its 1.0 Version across Speech Modes and Languages? Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 2584–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalayah, K.M.; Senan, E.M.; Atlam, H.F.; Ahmed, I.A.; Shatnawi, H.S.A. Automatic and Early Detection of Parkinson’s Disease by Analyzing Acoustic Signals Using Classification Algorithms Based on Recursive Feature Elimination Method. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.M.; Ata, O.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alghamdi, S.; Almehmadi, M. Hybrid Feature Selection Framework for the Parkinson Imbalanced Dataset Prediction Problem. Medicina 2021, 57, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karapinar Senturk, Z. Early Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 138, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Srivastav, S.; Shaffer, J.G.; Abraham, K.E.; Naandam, S.M.; Kakraba, S. Optimizing Parkinson’s Disease Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Data Aggregation Methods Using Multiple Voice Recordings via an Automated Artificial Intelligence Pipeline. Data 2025, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Saba, T.; Mujahid, M.; Alamri, F.S.; ElHakim, N. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Hybrid LSTM-GRU Deep Learning Model. Electronics 2023, 12, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjaidji, E.; Amara Korba, M.C.; Khelil, K. Improving Detection of Parkinson’s Disease with Acoustic Feature Optimization Using Particle Swarm Optimization and Machine Learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2025, 6, 015026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireš, M.; Drotár, P.; Pah, N.D.; Ngo, Q.C.; Kumar, D.K. On the Inter-Dataset Generalization of Machine Learning Approaches to Parkinson’s Disease Detection from Voice. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2023, 179, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Ramachandran, P. Novel Multistage Deep Convolution Neural Network-Based Parkinson’s Disease Detection and Severity Grading of Running Speech Using LSF Spectrums for Detection and STFT Spectrums for Grading. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintalapudi, N.; Battineni, G.; Hossain, M.A.; Amenta, F. Cascaded Deep Learning Frameworks in Contribution to the Detection of Parkinson’s Disease. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, L.; Maqsood, M.; Durrani, M.Y.; Bakhtyar, M.; Baber, J.; Jamal, H.; Mehmood, I.; Song, O.-Y. A Spectrogram-Based Deep Feature Assisted Computer-Aided Diagnostic System for Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 35482–35495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.V.K.; Sahu, S.S. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Hybrid Siamese Neural Network and Support Vector Machine in Multilingual Voice Signal. J. Voice 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Mortezaagha, P.; Rahgozar, A. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Diagnose Early Parkinson’s Disease via Voice Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, K.; Jayanthi, N.; Kumar, M. High-Resolution Superlet Transform Based Techniques for Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Speech Signal. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 214, 109657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Kemp, A.; Rahmatallah, Y.; Pillai, L.; Glover, A.; Prior, F.; Larson-Prior, L.; Virmani, T. A Machine Learning Method to Process Voice Samples for Identification of Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girdhar, R.; El-Nouby, A.; Liu, Z.; Singh, M.; Alwala, K.V.; Joulin, A.; Misra, I. ImageBind One Embedding Space to Bind Them All. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 15180–15190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communication, S.; Barrault, L.; Chung, Y.-A.; Meglioli, M.C.; Dale, D.; Dong, N.; Duquenne, P.-A.; Elsahar, H.; Gong, H.; Heffernan, K.; et al. SeamlessM4T: Massively Multilingual & Multimodal Machine Translation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.11596. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan, R.; Kumar, M.; Arya, S.; Mendirtta, N.; Kumar, S.; Towfek, S.K.; Khafaga, D.S.; Alkahtani, H.K.; Abdelhamid, A.A. A Novel Artificial-Intelligence-Based Approach for Classification of Parkinson’s Disease Using Complex and Large Vocal Features. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Javeed, A.; Noor, A.; Rauf, H.T.; Kadry, S.; Gandomi, A.H. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Based on Features Refinement through L1 Regularized SVM and Deep Neural Network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, G.; Başaran, E. Proposing a New Approach Based on Convolutional Neural Networks and Random Forest for the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease from Speech Signals. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 211, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempíř, O.; Krupička, R. Analyzing Wav2Vec 1.0 Embeddings for Cross-Database Parkinson’s Disease Detection and Speech Features Extraction. Sensors 2024, 24, 5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Cesarini, V.; Di Leo, P.; Amato, F.; Suppa, A.; Asci, F.; Pisani, A.; Calculli, A.; Saggio, G. Artificial Intelligence-Based Voice Assessment of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Off and On Treatment: Machine vs. Deep-Learning Comparison. Sensors 2023, 23, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Park, S.-B. Vocal Feature Extraction-Based Artificial Intelligent Model for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran Reddy, M.; Alku, P. Automatic Detection of Parkinsonian Speech Using Wavelet Scattering Features. JASA Express Lett. 2025, 5, 055202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammri, R.; Alharbi, G.; Alharbi, E.; Almubark, I. Machine Learning Approaches to Identify Parkinson’s Disease Using Voice Signal Features. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, K.; Jaisankar, N. Design of an Early Prediction Model for Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 17457–17472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, O.; Çakın, H.; Alhudhaif, A.; Polat, K. Robust Automated Parkinson Disease Detection Based on Voice Signals with Transfer Learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 178, 115013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.C.; Pah, N.D.; Ngo, Q.C.; Yoshida, A.; Gomes, N.B.; Papa, J.P.; Kumar, D. A Pilot Study for Speech Assessment to Detect the Severity of Parkinson’s Disease: An Ensemble Approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 185, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pah, N.D.; Indrawati, V.; Kumar, D.K. Voice-Based SVM Model Reliability for Identifying Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 144296–144305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, N.P.; Schuller, B.; Alku, P. The Detection of Parkinson’s Disease from Speech Using Voice Source Information. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, W. Exploiting Smartphone Voice Recording as a Digital Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S Band, S.; Yarahmadi, A.; Hsu, C.-C.; Biyari, M.; Sookhak, M.; Ameri, R.; Dehzangi, I.; Chronopoulos, A.T.; Liang, H.-W. Application of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Medical Health: A Systematic Review of Interpretability Methods. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 40, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Xie, W.; Pang, M.; Li, Y.; Jin, L.; Huang, F.; Shao, X. Non-Invasive Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Based on Speech Analysis and Interpretable Machine Learning. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1586273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, J.P.; Paygude, P.; Daimary, R.; Prasad, S. Advanced Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Early Parkinson’s Disease Detection Using Vocal Biomarkers. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251342878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meral, M.; Ozbilgin, F.; Durmus, F. Fine-Tuned Machine Learning Classifiers for Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease Using Vocal Characteristics: A Comparative Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaman Kadhim, M.; Al-Shammary, D.; Sufi, F. A Novel Voice Classification Based on Gower Distance for Parkinson Disease Detection. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2024, 191, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Ramadass, P.; Mathivanan, S.K.; Panneer Selvam, K.; Shivahare, B.D.; Shah, M.A. Detection of Parkinson Disease Using Multiclass Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Swain, B.K.; Mishra, M. Early Parkinson’s Disease Identification via Hybrid Feature Selection from Multi-Feature Subsets and Optimized CatBoost with SMOTE. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2025, 13, 2498909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veetil, I.K.; Sowmya, V.; Orozco-Arroyave, J.R.; Gopalakrishnan, E.A. Robust Language Independent Voice Data Driven Parkinson’s Disease Detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 129, 107494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Correa, J.C.; Rios-Urrego, C.D.; Arias-Vergara, T.; Schuster, M.; Rusz, J.; Nöth, E.; Orozco-Arroyave, J.R. Transfer Learning Helps to Improve the Accuracy to Classify Patients with Different Speech Disorders in Different Languages. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 150, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Tripathi, P. An Ensemble Technique to Predict Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Speech Commun. 2024, 159, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, S.; Hao, A.; Hou, X. TalkingStyle: Personalized Speech-Driven 3D Facial Animation with Style Preservation. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 4682–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamasco, L.; Coletta, A.; Olmo, G.; Cermelli, A.; Rubino, E.; Rainero, I. AI-Based Facial Emotion Analysis for Early and Differential Diagnosis of Dementia. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sedigh Malekroodi, H.; Lee, B.-i.; Yi, M. Voice-Based Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine and Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111279

Sedigh Malekroodi H, Lee B-i, Yi M. Voice-Based Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine and Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(11):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111279

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedigh Malekroodi, Hadi, Byeong-il Lee, and Myunggi Yi. 2025. "Voice-Based Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine and Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review" Bioengineering 12, no. 11: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111279

APA StyleSedigh Malekroodi, H., Lee, B.-i., & Yi, M. (2025). Voice-Based Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using Machine and Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering, 12(11), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111279