1. Introduction

Sufficient and stable cerebral perfusion is essential for delivering oxygen and nutrients to brain neurons and timely removing metabolic wastes, thereby ensuring the normal operation of the brain’s various complex functions. Abnormal cerebral perfusion may trigger a series of neurological diseases [

1]. Therefore, real-time monitoring of cerebral perfusion is of great significance for the early diagnosis of diseases, the formulation and adjustment of treatment plans, and the assessment of therapeutic efficacy.

Total aortic arch replacement (TAAR) has been identified as a cardiac surgery with a high incidence of cerebral damage [

2]. According to the Expert Consensus on Prevention and Treatment of Perioperative Cerebral Injury in Cardiac Surgery, mannitol dehydration is a customary postoperative treatment employed to avert and address cerebral damage-induced poor perfusion [

3]. However, further exploration and quantification are required to ascertain the impact of dehydration therapy on cerebral perfusion in patients with normal cerebral function and those with ND. Meanwhile, dynamic monitoring of cerebral perfusion is required to prevent disease deterioration. Consequently, there is an urgent need for technology capable of bedside real-time monitoring of cerebral perfusion in critically ill patients following TAAR.

Current imaging technologies for detecting cerebral perfusion include computed tomography perfusion (CTP), perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (PWI), and positron emission tomography (PET). Although these technologies can provide high-resolution images, they are limited by bulky equipment, radiation exposure, stringent environmental requirements, and high risks of patient transfer, making bedside real-time monitoring hard [

4]. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) only reflects hemodynamic information of large intracranial blood vessels and cannot provide images of global cerebral perfusion distribution [

5]. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) enables non-invasive monitoring of regional cerebral oxygen saturation to indirectly evaluate cerebral perfusion. However, its application is restricted by limited inability to detect perfusion changes in deep brain tissues and susceptibility to interference [

6]. Consequently, there is an urgent clinical need for a bedside monitoring technology that is convenient, real-time, visualizable, and sensitive to cerebral perfusion changes.

Electrical impedance properties are important physical attributes of biological tissues. They are not only directly related to cell morphology, structure, and arrangement patterns, but also closely associated with functional states such as tissue electrical activity and blood circulation. This enables them to promptly and sensitively reflect the physiological and pathological changes in tissues. Electrical impedance tomography (EIT), an emerging functional imaging technology [

7], involves the injection of safe currents into the target area via surface electrodes, the measurement of boundary voltages, and the acquisition of information regarding the spatial distribution of electrical impedance. This information reflects the pathological and physiological states of tissues. EIT has the advantages of non-invasiveness, no radiation, bedside real-time monitoring, and high sensitivity to tissue function alterations. Its potential in real-time observation of physiological and pathological processes has been demonstrated [

8]. Holder et al. utilized EIT to monitor impedance changes throughout the seizure process and localize the epileptic focus based on imaging, whilst also performing real-time imaging of neural activity in the brain [

9,

10,

11]. Yang et al. utilized EIT to monitor alterations in impedance in patients with cerebral edema during mannitol dehydration therapy. It was determined that EIT could monitor alterations in water content, which were significantly correlated with intracranial pressure (ICP) [

12]. Xu et al. further successfully detected cerebral perfusion abnormalities caused by cerebral infarction using contrast-enhanced EIT. But real-time cerebral perfusion monitoring was not achievable due to the need for contrast agent injection [

13]. Cerebral blood flow exhibits pulsatility with the heartbeat, and induces pulsatile changes in cerebral impedance due to the significant difference in resistivity between blood and brain tissue [

14]. DCP-EIT is a new functional cerebral perfusion imaging technology developed based on EIT. By accurately acquiring this pulsatile impedance signal and performing image reconstruction, it obtains real-time cerebral perfusion distribution information. It features high speed, high precision, and the capability for long-term monitoring. A DCP-EIT system was developed by our team to rapidly and accurately capture weak signals caused by cerebral blood perfusion [

15]. Furthermore, the detection of poor perfusion and the real-time monitoring of perfusion status changes caused by ICP changes were realized [

16]. Although our team has verified the technical feasibility of DCP-EIT in animals or healthy volunteers, problems such as how to scientifically and effectively monitor cerebral perfusion in patients in clinical settings and quantitatively evaluate the impact of treatment plans on cerebral perfusion to guide individualized treatment remain unsolved.

This study explores the feasibility and clinical value of DCP-EIT for bedside cerebral perfusion monitoring in patients after TAAR, and conducts the following research: (1) Exploring whether DCP-EIT can achieve visual monitoring of dynamic changes in cerebral perfusion during mannitol dehydration; (2) extracting relevant perfusion parameters to quantify their variation patterns; (3) investigating whether there are differences in the variation patterns of perfusion parameters between patients with normal neurological function and ND; (4) preliminarily exploring whether there is spatial correspondence between perfusion abnormal regions detected by DCP-EIT and brain damage regions indicated by CT. This study provides a foundation for the subsequent wide application of EIT in cerebral perfusion monitoring and the evaluation of treatment efficacy in other patients with cerebral injury, as well as the promotion of individualized cerebral protection strategies and precision medicine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a single-center prospective observational study. Eligible patients in the clinical trial included those who (a) underwent TAAR; (b) were 18–75 years old, regardless of gender; (c) had their hair shaved; (d) received mannitol dehydration therapy; (e) received postoperative DCP-EIT monitoring. In addition, patients were excluded if they (a) had cerebral wounds or acute inflammation, intracerebral or skull metal implants, preoperative examination indicating cerebrovascular malformation or cerebral tumor; (b) were allergic to electrodes; (c) did not sign the informed consent or withdrew midway; (d) had hepatic or renal insufficiency; (e) were deemed unsuitable for inclusion by researchers for other reasons.

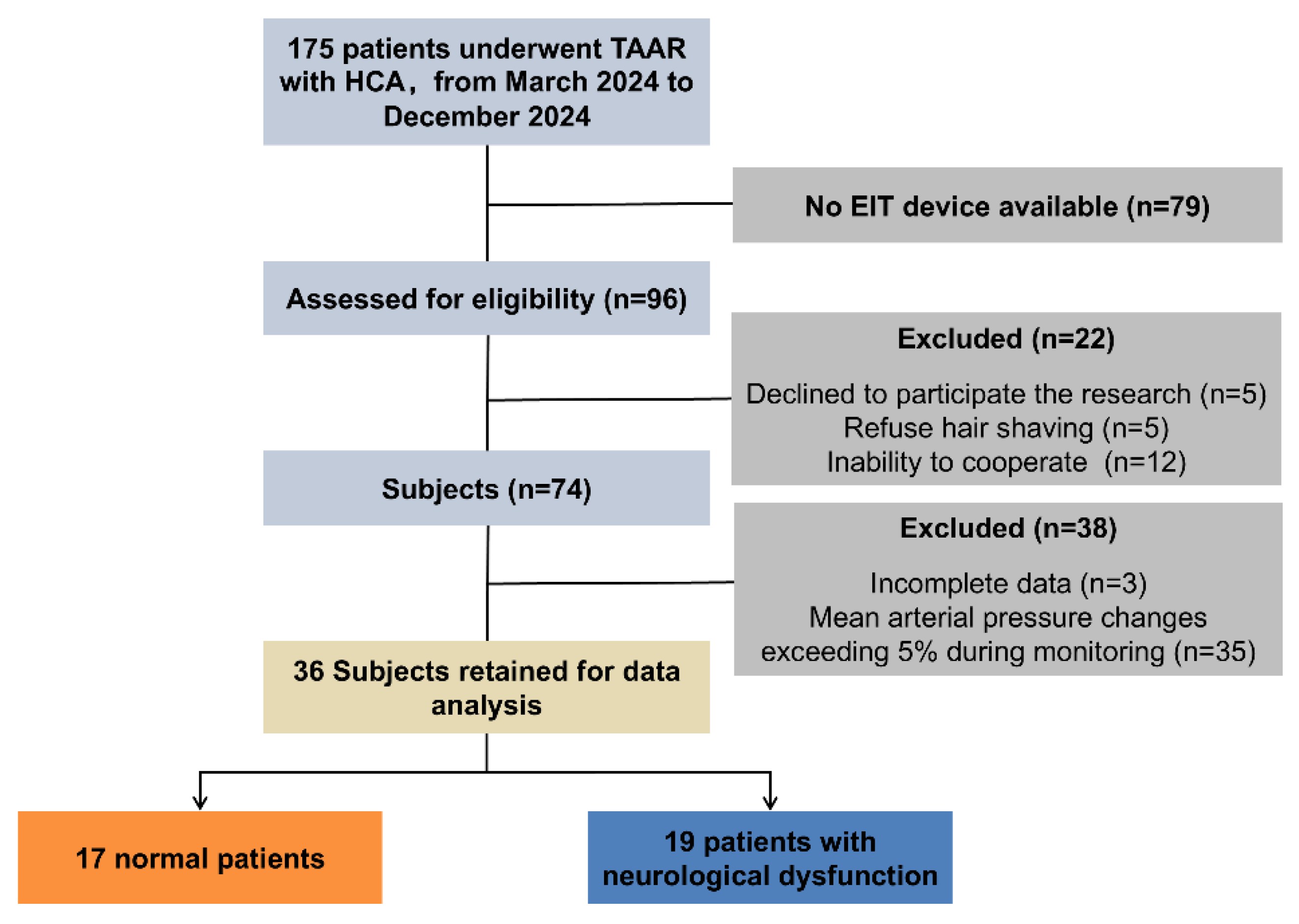

As demonstrated in

Figure 1, a total of 96 patients who underwent TAAR in the Department of Cardiac Surgery of the First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University and were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) from March 2024 to December 2024 were screened in this study, among which 74 patients underwent cerebral perfusion monitoring. Given the impact of significant changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) on cerebral perfusion, the present study focused on exploring the impact of mannitol dehydration therapy on cerebral perfusion. To this end, 35 cases with MAP relative changes exceeding 5% and 3 cases with incomplete data were excluded. Finally, data from 36 patients were included for analysis.

2.2. Standardized Assessment of Neurological Dysfunction and Grouping

For patients admitted to the ICU following TAAR, the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale was used to assess sedation levels, the Confusion Assessment Method for Intensive Care Unit was employed to evaluate delirium, the Lovett grading system was used to determine muscle strength, and the Glasgow Coma Scale was used to ascertain whether the patient was comatose, once a day within 7 days after surgery [

17,

18]. Concurrently, a CT scan was performed as soon as possible when the patient’s condition remained stable to determine whether a new stroke had occurred. All assessments were conducted by two neurology specialists to ensure consistency; in the event of disputes, a third specialist made the final decision. Patients were divided into the normal group and the ND group based on the aforementioned diagnostic results.

2.3. Cerebral Perfusion EIT Monitoring Protocol

As demonstrated in

Figure 2A, the EC-100 PRO, developed by our team, was used for data collection [

15]. This system operates within the frequency range of 10–250 kHz, can generate programmable current of 10–1250 μA, and exhibits a signal-to-noise ratio that exceeds 90 dB. In this study, the current was set to 1 mA and the operating frequency was 50 kHz. The system measured 40 frames of data per second to capture cerebral blood perfusion signals during the cardiac cycle.

Cerebral perfusion monitoring of the patient was performed within 24 h postoperatively. Sixteen Ag-AgCl electrodes (EH-PET-16-CS, Yongchuan Technology, Hangzhou, China) were placed at equal intervals on the cross-section 1 cm above the patient’s ears. Meanwhile, the electrodes were wrapped with medical bandages to prevent electrode displacement. Monitoring of cerebral perfusion status during mannitol dehydration therapy was initiated when the patient’s condition was relatively stable.

As shown in

Figure 2B, the EIT system was warmed up for at least 20 min before data collection, followed by 10 min of baseline data collection. Then, 0.5 g/kg mannitol was intravenously administered into each patient within 20 min for cerebral dehydration, and data were monitored for 100 min following the completion of dehydration. Concurrently, a physiological parameter monitor was used to assess the patient’s oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate.

2.4. Dynamic Cerebral Perfusion EIT Imaging

Two validated methods developed by our team were employed to reduce and compensate for artifacts and data loss caused by patient movement during long-term monitoring [

19,

20]. For DCP-EIT imaging, the raw impedance data were initially subjected to 1–5 Hz band-pass filtering to obtain impedance signals related to cerebral blood perfusion. Subsequently, a finite element model segmented based on human brain CT images and including the actual distribution of electrodes was used for forward problem calculation. Conductivities of the scalp (0.44 S/m), skull (0.012 S/m), and brain parenchyma (0.15 S/m) were utilized as prior information to enhance imaging quality. Finally, the NOSER algorithm was used for inverse problem calculation and reconstruct the conductivity change distribution to obtain cerebral perfusion EIT images [

21], as shown in Equation (1):

In this equation, Δσ denotes the change in conductivity distribution between the foreground frame and the background frame, which reflects blood perfusion. ΔV signifies the corresponding change in boundary voltage measurements. J represents the Jacobian matrix, which encodes the relationship between a unit change in conductivity within each image element and the resulting change in measured voltages. λ is the regularization parameter, crucial for stabilizing the solution of this ill-posed problem by imposing constraints to find a physiologically plausible and smooth image, thereby reducing the impact of measurement noise and model errors. In this study, subsequent cerebral perfusion parameter extraction was conducted by taking the end-diastole of each cardiac cycle as the background frame and the entire cardiac pulsation process as the foreground frame. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of EIT and reduce the impact of physiological state fluctuations, 300 frames of data at each time point were used for perfusion status analysis.

The average reconstruction value (ARV) of the region of interest (ROI) in EIT images was calculated using Equation (2):

In this equation, ∆σi denotes the reconstructed conductivity of the i-th unit in the ROI, and N represents the total number of units in the ROI. In this study, the brain parenchyma region was selected as the ROI, and its ARV was calculated according to Equation (2).

2.5. Extraction of Cerebral Perfusion Parameters

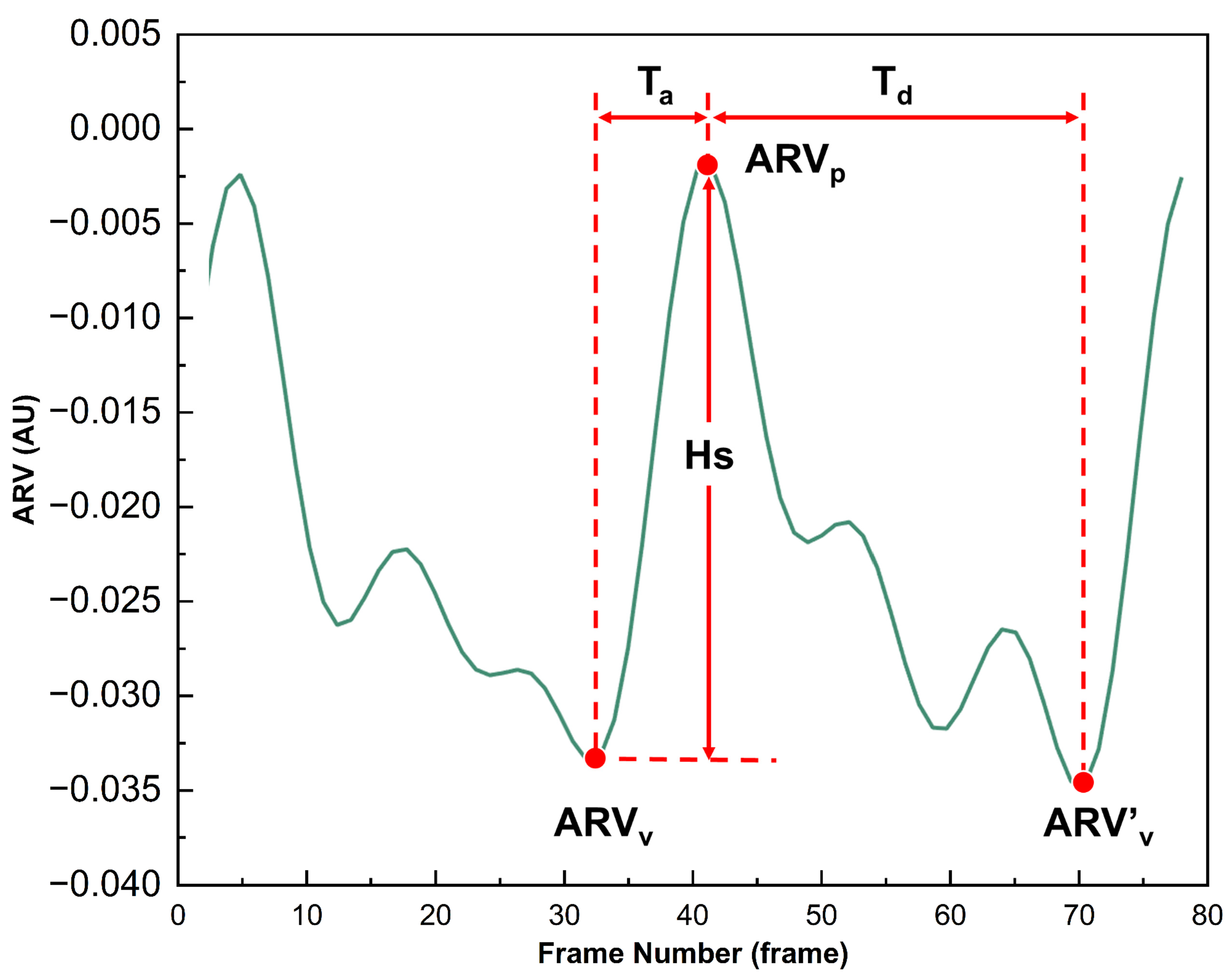

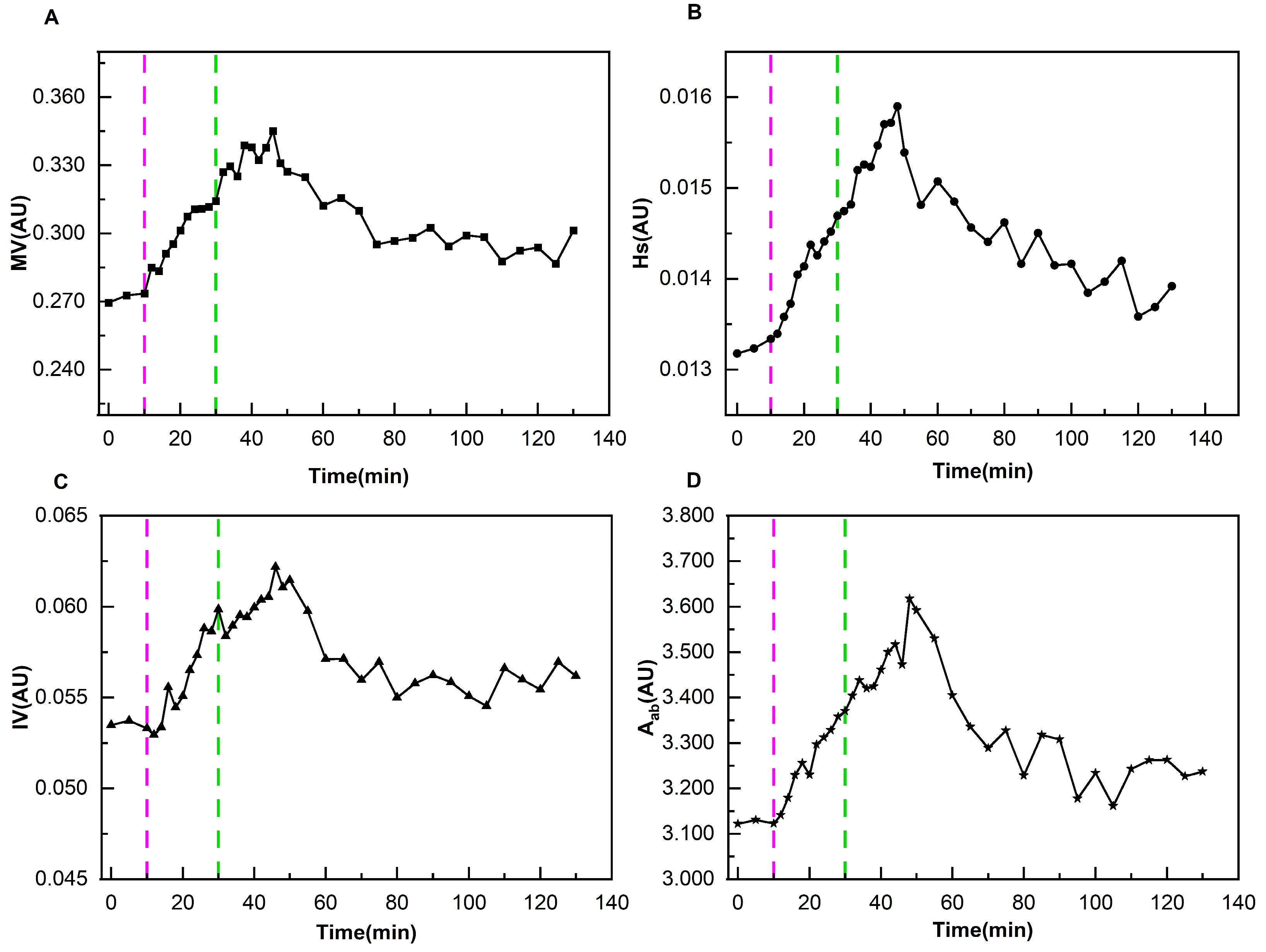

As demonstrated in

Figure 3, ARV can characterize the dynamic changes in conductivity caused by the congestion state of brain tissue with cardiac pulsation. During the systolic phase of the heart, when blood is pumped into the cranial cavity, the conductivity increases significantly, and the ARV rises from the valley (ARV

v) to the peak (ARV

p). This process is defined as the ascending branch, corresponding to a time span of T

a. Subsequently, during the diastolic phase of the heart, blood gradually flows out of the cranial cavity, which is reflected by the decrease in ARV from the peak (ARV

p) to the next trough (ARV

v’). This process corresponds to a time span of T

d. A complete cerebral perfusion cycle is defined as commencing at ARV

v and concluding at ARV

v’. For this perfusion process, four perfusion parameters (MV, Hs, IV, A

ab) were extracted. Their extraction equations and corresponding physiological meanings can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

To effectively eliminate differences between individual perfusion parameters and summarize the change patterns of all patients during dehydration, the following data processing method was adopted: the average value X of perfusion parameters during the baseline period was used as the reference value for each patient. Each perfusion parameter Y at various time points during the entire monitoring process was divided by the reference value X, i.e., RY = Y/X, to obtain a series of relative ratios RY (where Y represents MV, Hs, IV, Aab, and RY represents RMV, RHs, RIV, RAab). This operation unified the perfusion parameters of different patients at different stages to a relative scale with their respective baseline averages as references. The purpose of this was to significantly improve the comparability of data and facilitate subsequent in-depth analysis and summary of the characteristics of the overall dehydration process.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage), and the chi-square test was used to compare differences between different types of patients. For continuous variables, the Shapiro–Wilk normality test was employed to ascertain the conformity of these variables to a normal distribution. In instances where the data conformed to a normal distribution, the data was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Conversely, if the data did not conform to a normal distribution, they were expressed as the median (interquartile range). The independent samples t-test or independent samples Mann–Whitney test was utilized to compare differences between different types of patients. To evaluate the impact of dehydration on cerebral perfusion, the one-sample t-test or one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess whether there was a significant difference between the relative cerebral perfusion parameters and the baseline data (1) during the monitoring process (α = 0.05).

4. Discussion

Mannitol dehydration is routinely used in patients after TAAR to prevent and treat potential cerebral damage. Nevertheless, the efficacy of this method in different patients remains uncertain, which hinders the implementation of accurate and effective treatment. Mannitol dehydration is principally employed to reduce cerebral edema, lower ICP, and thereby enhance cerebral perfusion [

22,

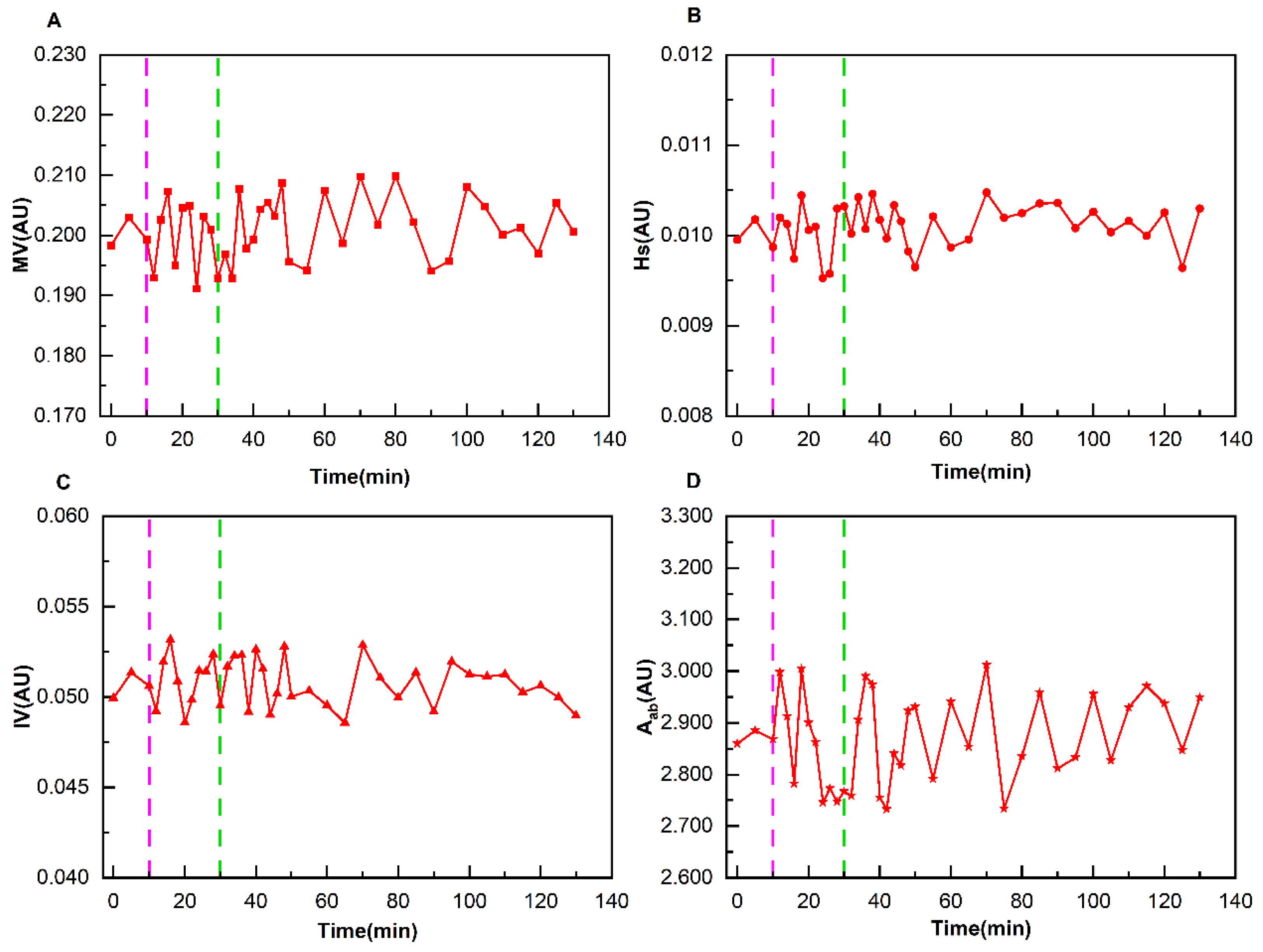

23]. However, there is currently no effective cerebral perfusion monitoring technology suitable for ICU use. This study innovatively used DCP-EIT to realize dynamic real-time monitoring of cerebral perfusion. Concurrently, a perfusion parameter system was established to quantitatively evaluate the therapeutic effect in normal and ND patients. It was found that the detected poorly perfused area by DCP-EIT roughly corresponded with the cerebral infarction area detected by CT. The four relative perfusion parameters of normal patients remained stable during dehydration. The perfusion status of ND patients showed obvious change patterns, with each perfusion parameter reaching its peak at 14–20 min following the completion of dehydration. And the perfusion status was still improved even at 100 min after the completion of dehydration. Through monitoring of patients’ cerebral perfusion, this study quantified the improvement effect of mannitol dehydration in different patients. The findings provide strong support for doctors to formulate and adjust treatment plans and evaluate therapeutic efficacy.

The central aim of this study is to elucidate the impact of mannitol dehydration on the cerebral perfusion of patients after TAAR. It is crucial to exclude patients with significant fluctuations in MAP, as this operation can effectively control confounding variables and ensure the validity of causal inference. The perfusion status of human brain is directly affected by cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), and CPP = MAP − ICP. Consequently, CPP is also significantly impacted by MAP. Healthy individuals have a well-developed cerebral autoregulation mechanism; when MAP changes within the range of 50–150 mmHg, the human brain can maintain stable cerebral blood flow through vasodilation and contraction [

24]. Post-TAAR patients often suffer from cerebral damage due to ischemia-hypoxia caused by the cessation of cardiopulmonary bypass and perfusion abnormalities during the cooling and rewarming stages. This makes the stability of the cerebral circulation extremely vulnerable and leads to impairment of the cerebral autoregulation mechanism. When the cerebral autoregulation mechanism of ND patients is impaired, the capacity to offset the impact of MAP fluctuations may be diminished. In this context, the signals collected by DCP-EIT may be affected not only by dehydration but also by MAP fluctuations. Consequently, patients with MAP changes exceeding 5% were excluded in this study.

Mannitol, a hypertonic solution of macromolecular substances, cannot cross the cell membrane or the intact blood–brain barrier (BBB) [

25]. Following intravenous injection of mannitol, plasma osmotic pressure increases significantly. This creates a marked transvascular concentration gradient, which causes small-molecule matter (such as H

2O, Na

+, and K

+) in brain tissue to diffuse into cerebral blood vessels [

26]. This diffusion, in turn, reduces brain water content, alleviates cerebral edema, and decreases brain volume, thereby lowering ICP to prevent neurological deterioration [

27], and further improving cerebral perfusion. However, improper use of mannitol may cause side effects, including reduced blood volume, electrolyte disorders, increased renal metabolic burden, and even secondary acute rebound of ICP [

28]. Therefore, it is crucial to accurately evaluate the efficacy of mannitol dehydration in different patients to optimize the treatment plan and provide a basis for individualized cerebral protection and precision medicine.

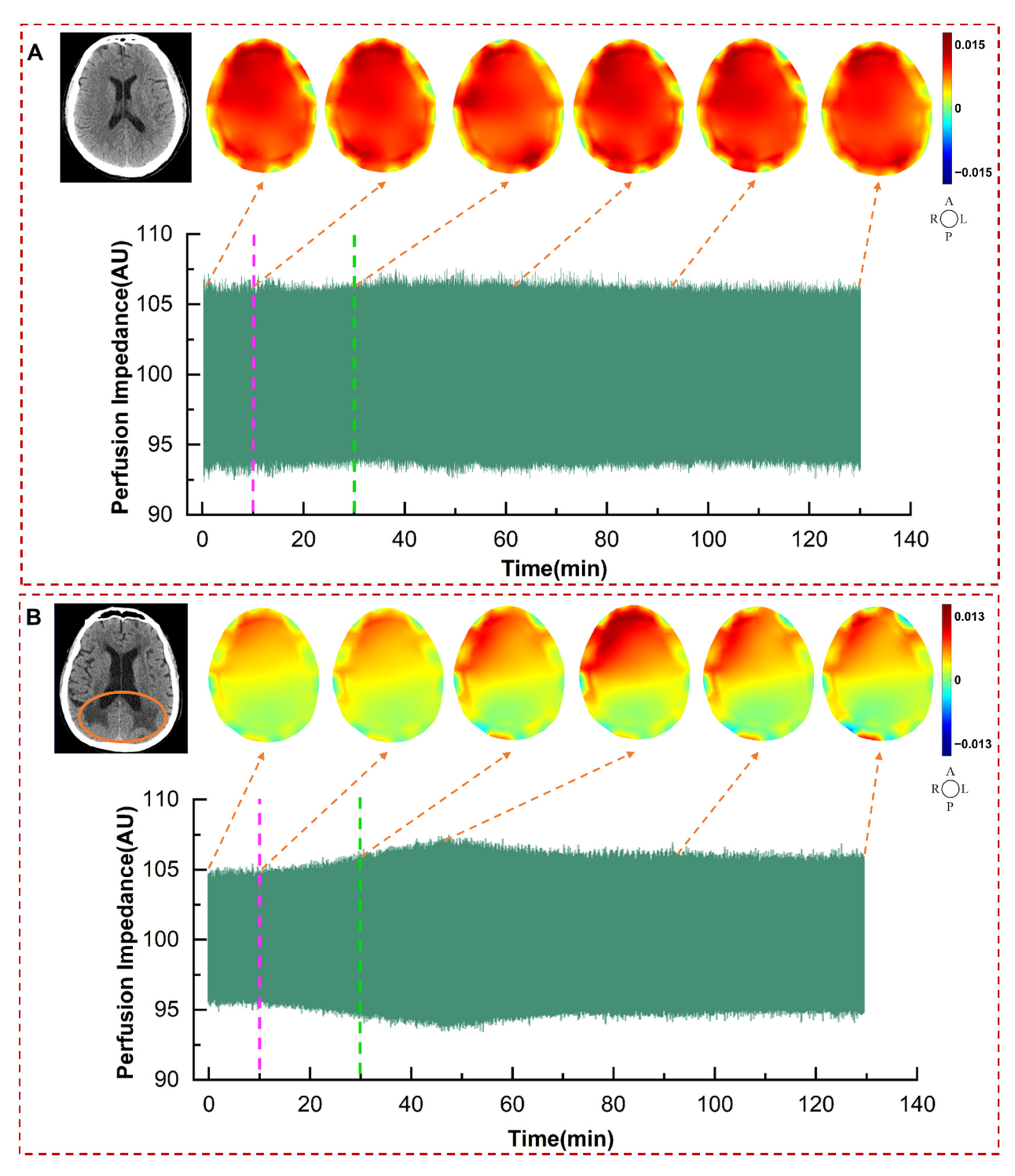

By comparing the cerebral perfusion EIT images and CT images of normal and ND patients in

Figure 4, it can be seen that the detected poorly perfused area by DCP-EIT roughly corresponds with the cerebral infarction area detected by CT. DCP-EIT overcomes the shortcomings of TCD and NIRS, which cannot reflect global cerebral perfusion or detect poor perfusion in deep brain regions. Another point to note is that due to the critical condition of the patients, postoperative patients could not timely undergo conventional imaging examinations (CT, MRI, PET). In this study, only a subset of patients underwent CT scans when possible, after their condition stabilized postoperatively. Furthermore, conventional imaging techniques are unable to provide real-time, dynamic, and long-term monitoring of changes in perfusion status. The detected alterations in perfusion images by DCP-EIT due to dehydration can help doctors dynamically, intuitively, conveniently, and accurately grasp the improvement of patients’ cerebral perfusion without relevant professional background.

The normal and ND patients exhibited divergent characteristics in cerebral perfusion changes during mannitol dehydration therapy. The four perfusion indicators of the normal group fluctuated around the baseline data, with no significant difference from the baseline data. The presumed mechanism is that mannitol-induced dehydration only mildly reduces ICP. Although this results in alterations to CPP, these are rapidly offset by the intact autoregulatory mechanisms present in the normal group. This ensures that perfusion parameters remain at a fundamentally stable level. In contrast, the perfusion parameters of the ND group exhibited regular changes with dehydration. Each perfusion parameter reached its peak at 14–20 min following the completion of dehydration, and the perfusion status continued to improve even at 100 min after dehydration. The reason for this phenomenon may be that ND patients usually exhibit varying degrees of decompensation of the cerebral autoregulation mechanism. When the ICP of ND patients decreases due to dehydration, the CPP increases.

In neurosurgery, ICP monitoring is usually used to help doctors evaluate the efficacy of dehydration therapy [

29,

30]. Placing sensors in the ventricle or parenchyma is the gold standard for accurate ICP detection, but it may result in complications such as intracranial hemorrhage and infection [

31]. It is important to note that patients following TAAR typically do not undergo invasive ICP monitoring, and not all patients exhibit cerebral damage. Consequently, there is no effective evaluation method for the therapeutic effect of dehydration therapy in both normal and ND patients. By using a high-speed and high-precision EIT system, the sampling frame rate was increased by 40 times compared with that of Yang, Xu et al. [

12,

13]. This enhancement enabled the successful capture of weak cerebral blood pulsation signals. Concurrently, the limitations of contrast-enhanced EIT, including its invasiveness due to contrast agent injection and inability to realize real-time monitoring, were surmounted.

This study is the first to apply high-speed and high-precision DCP-EIT to bedside monitor the cerebral perfusion of critically ill patients after TAAR. Concurrently, a quantitative evaluation method for mannitol dehydration efficacy was first achieved through the extraction and normalization of four perfusion parameters. On this basis, it was found for the first time that normal and ND patients have different sensitivities to mannitol dehydration, and their change patterns were clarified. These findings provide a tangible basis for clinical practice: for normal patients with stable perfusion, clinicians may avoid unnecessary mannitol dosage increases (reducing risks of electrolyte disorders and renal burden); for ND patients, the 14–20 min post-dehydration peak window can guide timed efficacy assessments, and the sustained perfusion improvement at 100 min supports optimized ICU monitoring schedules (e.g., reducing monitoring frequency).

DCP-EIT provides technical support for the implementation of individualized treatment, precision medicine and the reduction in risks associated with empirical medication, and offers a robust foundation for healthcare professionals to intuitively and scientifically evaluate the efficacy of dehydration, thereby avoiding the wastage of medical resources. The present study will promote the advancement of research in several domains. These include the mechanism of occurrence and development of perioperative cerebral injury, the exploration of cerebral function activities and cerebral science laws, precise management of stroke, and evaluation of therapeutic effects of traumatic brain injury. The study’s findings have the potential to be widely applied in scenarios such as neurocritical care, surgical anesthesia, and emergency rescue to realize bedside non-invasive real-time monitoring of cerebral perfusion in patients.

5. Limitations and Future Work

Due to the core imaging principle of inferring changes in internal impedance distribution from boundary voltage variations, EIT still has limitations: the inherent ill-posedness of its inverse problem leads to low spatial resolution. Moreover, it relies on regularization algorithms to balance reconstruction stability and image quality, which may easily introduce image reconstruction errors and make it difficult to capture subtle perfusion abnormalities. To address these limitations, future work will involve developing more advanced image reconstruction algorithms (e.g., integrating CT/MRI prior information), as well as adopting high-density electrode arrays.

To exclude the impact of MAP on cerebral perfusion, patients with MAP changes exceeding 5% were excluded in this study. This relatively strict threshold resulted in 35 patients not being included in subsequent analysis, leading to resource waste. In future studies, the adoption of different MAP change thresholds as inclusion and exclusion criteria will be explored to investigate the differences in cerebral perfusion changes between the two groups. On this basis, the change patterns of DCP-EIT under the combined action of MAP changes and mannitol dehydration will be investigated. Additionally, the perfusion parameters extracted reflect global cerebral conditions. To further refine the research, changes in perfusion parameters between normal brain regions and brain-injured regions in ND patients during dehydration will be investigated, based on lesions identified via CT or MRI.

Meanwhile, the present study is a single-center study. In the future, multi-center studies will be conducted. And cerebral perfusion monitoring in other types of patients in more clinical scenarios will be explored. Subsequent studies have the potential to analyze the prognosis of patients in relation to the varying responses of different patients’ cerebral perfusion to mannitol dehydration. This would facilitate the establishment of a more precise clinical prediction model.