Biomimetic Remineralization of Artificial Caries Lesions with a Calcium Coacervate, Its Components and Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

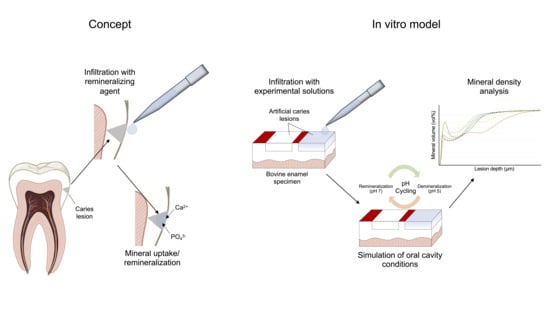

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.3. Specimen Treatment

2.4. Demineralization/pH Cycling

2.5. Transversal Microradiographic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

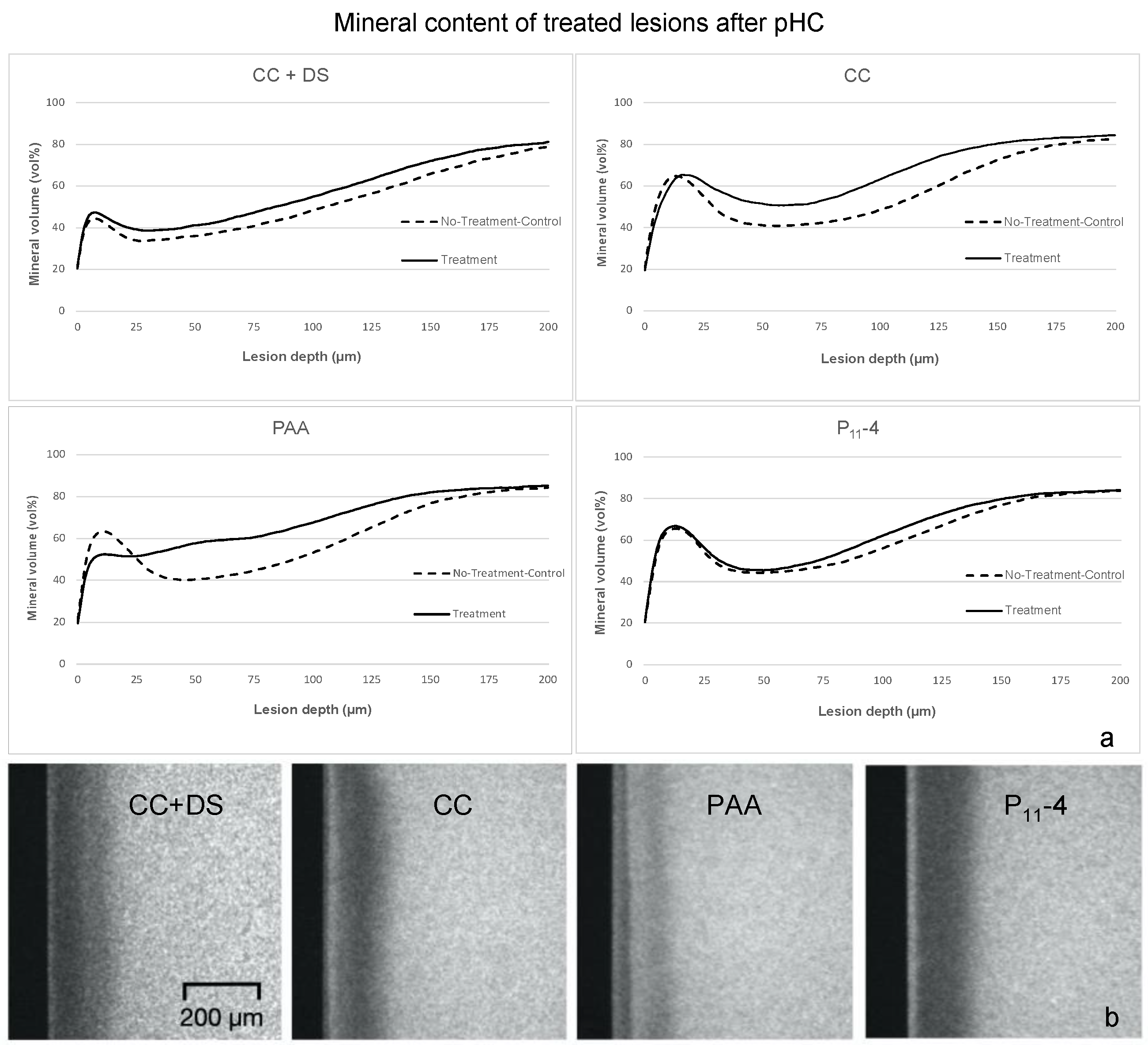

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fejerskov, O. Concepts of dental caries and their consequences for understanding the disease. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machiulskiene, V.; Campus, G.; Carvalho, J.C.; Dige, I.; Ekstrand, K.R.; Jablonski-Momeni, A.; Maltz, M.; Manton, D.J.; Martignon, S.; Martinez-Mier, E.A.; et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res. 2019, 54, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, K.R.; Ricketts, D.N.J.; Kidd, E.A.M.; Qvist, V.; Schou, S. Detection, Diagnosing, Monitoring and Logical Treatment of Occlusal Caries in Relation to Lesion Activity and Severity: An in vivo Examination with Histological Validation. Caries Res. 1998, 32, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorri, M.; Dunne, S.M.; Walsh, T.; Schwendicke, F. Micro-invasive interventions for managing proximal dental decay in primary and permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD010431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Schwendicke, F.; Keltsch, J.; Dörfer, C.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Masking of white spot lesions by resin infiltration in vitro. J. Dent. 2013, 41, e28–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Bitter, K.; Krois, J.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Seven-year-efficacy of proximal caries infiltration—Randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. 2020, 93, 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Christoffersen, J. The nature of early caries lesions in enamel. J. Dent. Res. 1986, 65, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, H.; Litman, A.; Margolis, H.C. Effect of fluoride on artificial caries lesion progression and repair in human enamel: Regulation of mineral deposition and dissolution under in vivo-like conditions. Arch. Oral Biol. 2007, 52, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, E.C. Calcium phosphate-based remineralization systems: Scientific evidence? Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlinsey, R.L.; Pfarrer, A.M. Fluoride plus functionalized β-TCP: A promising combination for robust remineralization. Adv. Dent. Res. 2012, 24, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, W.; Antoun, J.S.; Farella, M.; Mei, L. Long-term remineralizing effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) on early caries lesions in vivo: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, L.; Stevanovic, S.; Wuttig, S.; Wimberger, S.; Hofer, J.; Muller, B.; Pieles, U. Biomimetic Remineralization of Carious Lesions by Self-Assembling Peptide. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrapriyadharshini, K.; Madan Kumar, P.D.; Sharma, K.; Iyer, K. Remineralizing potential of CPP-ACP in white spot lesions—A systematic review. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Tao, S.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; He, L. Efficacy of fluorides and CPP-ACP vs fluorides monotherapy on early caries lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thierens, L.A.M.; Moerman, S.; Elst, C.V.; Vercruysse, C.; Maes, P.; Temmerman, L.; Roo, N.M.C.; Verbeeck, R.M.H.; Pauw, G.A.M. The in vitro remineralizing effect of CPP-ACP and CPP-ACPF after 6 and 12 weeks on initial caries lesion. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e20180589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkilzy, M.; Santamaria, R.M.; Schmoeckel, J.; Splieth, C.H. Treatment of Carious Lesions Using Self-Assembling Peptides. Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilzy, M.; Tarabaih, A.; Santamaria, R.M.; Splieth, C.H. Self-assembling Peptide P(11)-4 and Fluoride for Regenerating Enamel. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, J.; Firth, A.; Vernals, D.; Boden, N.; Robinson, C.; Shore, R.C.; Brookes, S.J.; Aggeli, A. Self-assembling Peptide Scaffolds Promote Enamel Remineralization. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilzy, M.; Qadri, G.; Splieth, C.H.; Santamaría, R.M. Biomimetic Enamel Regeneration Using Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhura, V.; Uloopi, K.S.; Vinay, C.; Chandrasekhar, R. Evaluation of enamel remineralizing potential of self-assembling peptide P(11)-4 on artificially induced enamel lesions in vitro. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2018, 36, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N. State of the Art Enamel Remineralization Systems: The Next Frontier in Caries Management. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.C.; Higgins, J.P.; Sheiham, A.; Logan, S. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 2003, CD002278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.C.; Worthington, H.V.; Walsh, T.; Chong, L.Y. Fluoride gels for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD002280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, V.C.; Chong, L.Y.; Worthington, H.V.; Walsh, T. Fluoride mouthrinses for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD002284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquhart, O.; Tampi, M.P.; Pilcher, L.; Slayton, R.L.; Araujo, M.W.B.; Fontana, M.; Guzmán-Armstrong, S.; Nascimento, M.M.; Nový, B.B.; Tinanoff, N.; et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharbot, B.; Bulgun, N.; Cölfen, H.; Paris, S. Effect of calcium-coacervate infiltration of artificial enamel caries lesions in de- and remineralizing conditions. J. Dent. 2024, 142, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gower, L.; Volkmer, D.; Cölfen, H. The existence region and composition of a polymer-induced liquid precursor phase for dl-glutamic acid crystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, D.; Colfen, H. Prenucleation Clusters and Nonclassical Nucleation. Nano Today 2011, 6, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehannin, M.; Rao, A.; Colfen, H. New Horizons of Nonclassical Crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10120–10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cölfen, H.; Antonietti, M. Mesocrystals and Nonclassical Crystallization; WILEY: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Yoreo, J.J.; Gilbert, P.U.; Sommerdijk, N.A.; Penn, R.L.; Whitelam, S.; Joester, D.; Zhang, H.; Rimer, J.D.; Navrotsky, A.; Banfield, J.F.; et al. CRYSTAL GROWTH. Crystallization by particle attachment in synthetic, biogenic, and geologic environments. Science 2015, 349, aaa6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara-Narutaki, A.; Nakamura, J.; Ohtsuki, C. 17—Polymer-induced liquid precursors (PILPs) and bone regeneration. In Bioceramics; Osaka, A., Narayan, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, F.R.; Pashley, D.H. Guided tissue remineralisation of partially demineralised human dentine. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.Y.; Mei, M.L.; Li, Q.-L.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Methods for Biomimetic Remineralization of Human Dentine: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 4615–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamitakahara, M.; Kawashita, M.; Kokubo, T.; Nakamura, T. Effect of polyacrylic acid on the apatite formation of a bioactive ceramic in a simulated body fluid: Fundamental examination of the possibility of obtaining bioactive glass-ionomer cements for orthopaedic use. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3191–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurrohman, H.; Carter, L.; Barnes, N.; Zehra, S.; Singh, V.; Tao, J.; Marshall, S.J.; Marshall, G.W. The Role of Process-Directing Agents on Enamel Lesion Remineralization: Fluoride Boosters. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaie, E.; Bacino, M.; White, J.; Nurrohman, H.; Marshall, G.W.; Saeki, K.; Habelitz, S. Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor (PILP) remineralization of artificial and natural dentin carious lesions evaluated by nanoindentation and microcomputed tomography. J. Dent. 2021, 109, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, F.R.; Pashley, D.H. Biomimetic remineralization of resin-bonded acid-etched dentin. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.; Mura, S.; Brambilla, D.; Mackiewicz, N.; Couvreur, P. Design, functionalization strategies and biomedical applications of targeted biodegradable/biocompatible polymer-based nanocarriers for drug delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1147–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, C.E.; Perry, S.L. Recent progress in the science of complex coacervation. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 2885–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, H.G.B.; Kruyt, H.R. Koazervation. Kolloid-Z. 1930, 50, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungenberg de Jong, H.G. Wissenschaftliche und technische Sammelreferate: Koazervation, I. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1937, 79, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Huang, J.; Lee, Y.; Dutta, S.; Yoo, H.Y.; Jung, Y.M.; Jho, Y.; Zeng, H.; Hwang, D.S. Complexation and coacervation of like-charged polyelectrolytes inspired by mussels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E847–E853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blocher, W.C.; Perry, S.L. Complex coacervate-based materials for biomedicine. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, e1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buskes, J.A.; Christoffersen, J.; Arends, J. Lesion formation and lesion remineralization in enamel under constant composition conditions. A new technique with applications. Caries Res. 1985, 19, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, G.B.; Shellis, P. Infiltration of resin into white spot caries-like lesions of enamel: An in vitro study. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2002, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aggeli, A.; Bell, M.; Boden, N.; Keen, J.N.; Knowles, P.F.; McLeish, T.C.; Pitkeathly, M.; Radford, S.E. Responsive gels formed by the spontaneous self-assembly of peptides into polymeric beta-sheet tapes. Nature 1997, 386, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, A.K.; Shetty, D.C.; Bindal, R.; Pathak, A. Amelogenin: A novel protein with diverse applications in genetic and molecular profiling. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2012, 16, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidlin, P.; Zobrist, K.; Attin, T.; Wegehaupt, F. In vitro re-hardening of artificial enamel caries lesions using enamel matrix proteins or self-assembling peptides. J. Appl. Oral Sci. Rev. FOB 2016, 24, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggeli, A.; Bell, M.; Carrick, L.M.; Fishwick, C.W.G.; Harding, R.; Mawer, P.J.; Radford, S.E.; Strong, A.E.; Boden, N. pH as a Trigger of Peptide β-Sheet Self-Assembly and Reversible Switching between Nematic and Isotropic Phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9619–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröseler, F.; Tietmann, C.; Bommer, C.; Drechsel, T.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Jepsen, S. Randomised clinical trial investigating self-assembling peptide P(11)-4 in the treatment of early caries. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberdoli, D.; Bommer, C.; Begzati, A.; Haliti, F.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Juric, H. Randomized Clinical Trial investigating Self-Assembling Peptide P(11)-4 for Treatment of Early Occlusal Caries. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözetici, B.; Öztürk-Bozkurt, F.; Toz-Akalın, T. Comparative Evaluation of Resin Infiltration and Remineralisation of Noncavitated Smooth Surface Caries Lesions: 6-month Results. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2019, 17, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamh, R.; Niazy, M.; El-Yasaky, M. Clinical Performance and Remineralization Potential of Different Biomimitic Materials on White Spot Lesions. Al-Azhar Dent. J. Girls 2018, 5, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atteya, S.M.; Amer, H.A.; Saleh, S.M.; Safwat, Y. Self-assembling peptide and nano-silver fluoride in remineralizing early enamel carious lesions: Randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, D.N. Adsorption of Polyacrylic Acids and Their Sodium Salts on Hydroxyapatite: Effect of Relative Molar Mass. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 181, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Gu, X.; Xu, X.; Pan, H.; Tang, R. Remineralization of dentin collagen by meta-stabilized amorphous calcium phosphate. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 6151–6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.K.; Hauschka, P.V.; Poole, A.R.; Rosenberg, L.C.; Goldberg, H.A. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochem. J. 1996, 317 Pt 1, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellberg, J.R. Hard-tissue substrates for evaluation of cariogenic and anti-cariogenic activity in situ. J. Dent. Res. 1992, 71, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, R.B.; Haiter-Neto, F.; Fernandes-Neto, A.J.; Barbosa, G.A.; Soares, C.J. Radiodensity of enamel and dentin of human, bovine and swine teeth. Arch. Oral Biol. 2004, 49, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellberg, J.R.; Loertscher, K.L. Comparison of in vitro fluoride uptake by human and bovine enamel from acidulated phosphate-fluoride solutions. J. Dent. Res. 1974, 53, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Cate, J.M.; Timmer, K.; Shariati, M.; Featherstone, J.D. Effect of timing of fluoride treatment on enamel de- and remineralization in vitro: A pH-cycling study. Caries Res. 1988, 22, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.J. The application of in vitro models to research on demineralization and remineralization of the teeth. Adv. Dent. Res. 1995, 9, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzalaf, M.A.; Hannas, A.R.; Magalhães, A.C.; Rios, D.; Honório, H.M.; Delbem, A.C. pH-cycling models for in vitro evaluation of the efficacy of fluoridated dentifrices for caries control: Strengths and limitations. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2010, 18, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.J.; Featherstone, J.D. A longitudinal microhardness analysis of fluoride dentifrice effects on lesion progression in vitro. Caries Res. 1987, 21, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Treatment Agent | Post-Treatment Exposition |

|---|---|---|

| CC | Calcium–coacervate solution | pH cycling |

| CC + DS | Calcium–coacervate solution | Demineralization solution |

| PAA | Polyacrylic acid solution | pH cycling |

| P11-4 | Self-assembling peptide (CurodontTM Repair) | pH cycling |

| PO4 | K2HPO4 | pH cycling |

| Ca | CaCl2·2 H2O | pH cycling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kharbot, B.; Askar, H.; Gruber, D.; Paris, S. Biomimetic Remineralization of Artificial Caries Lesions with a Calcium Coacervate, Its Components and Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 In Vitro. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11050465

Kharbot B, Askar H, Gruber D, Paris S. Biomimetic Remineralization of Artificial Caries Lesions with a Calcium Coacervate, Its Components and Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 In Vitro. Bioengineering. 2024; 11(5):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11050465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKharbot, Basel, Haitham Askar, Dominik Gruber, and Sebastian Paris. 2024. "Biomimetic Remineralization of Artificial Caries Lesions with a Calcium Coacervate, Its Components and Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 In Vitro" Bioengineering 11, no. 5: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11050465

APA StyleKharbot, B., Askar, H., Gruber, D., & Paris, S. (2024). Biomimetic Remineralization of Artificial Caries Lesions with a Calcium Coacervate, Its Components and Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 In Vitro. Bioengineering, 11(5), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11050465