The Influence of Human Factors Training in Air Rescue Service on Patient Safety in Hospitals: Results of an Online Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

- -

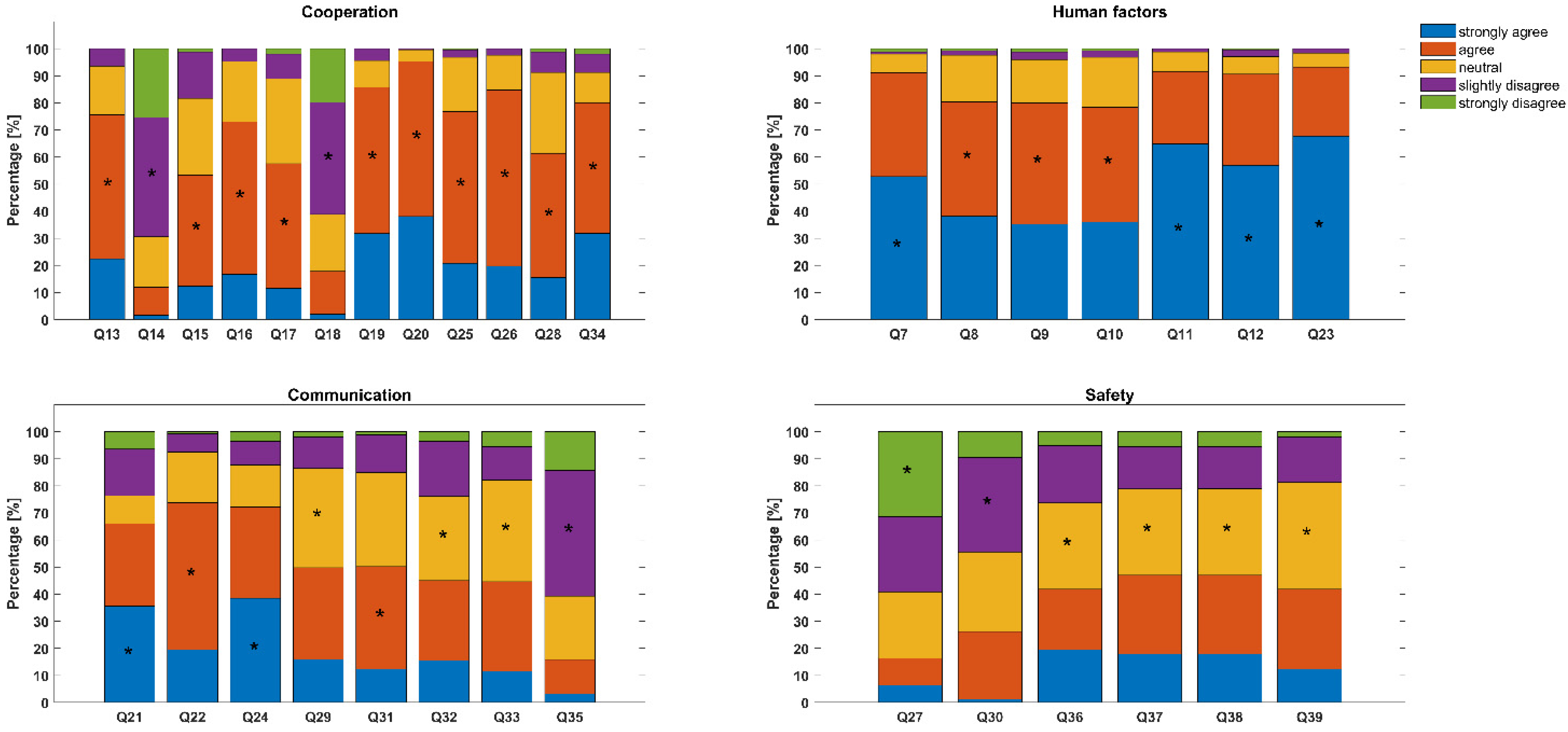

- Scale I (“Cooperation”): Q13, Q14, Q15, Q16, Q17, Q18, Q19, Q20, Q25, Q26, Q28, Q34;

- -

- Scale II (“Human factors”): Q7, Q8, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q12, Q23;

- -

- Scale III (“Communication”): Q21, Q22, Q24, Q29, Q31, Q32, Q33, Q35;

- -

- Scale IV (“Safety”): Q27, Q30, Q36, Q37, Q38, Q39.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.E.; Welsh, D.E.; Paull, D.E.; Knowles, R.S.; DeLeeuw, L.D.; Hemphill, R.R.; Essen, K.E.; Sculli, G.L. The effects of crew resource management on teamwork and safety climate at Veterans Health Administration facilities. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2018, 38, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmreich, R.L. Managing human error in aviation. Sci. Am. 1997, 276, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, H. Development of an Educational Program for the Helicopter Emergency Medical Services in Japan. Air Med. J. 2013, 32, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Spall, H.; Kassam, A.; Tollefson, T.T. Near-misses are an opportunity to improve patient safety: Adapting strategies of high reliability organizations to healthcare. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 23, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, R.; Münzberg, M.; Stange, R.; Rüsseler, M.; Egerth, M.; Bouillon, B.; Hoffmann, R.; Mutschler, M. Interpersonal competence in orthopedics and traumatology. Unfallchirurg 2016, 119, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, H.B.; Abrahamsen, E.B.; Lossius, H.M. Safety culture in the air ambulance services. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2012, 132, 797–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.; Porter, M.; Cody, P.; Williams, B. Can a targeted educational approach improve situational awareness in paramedicine during 911 emergency calls? Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 63, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.; Porter, M.; Williams, B. What Is Known About Situational Awareness in Paramedicine? A Scoping Review. J. Allied Health 2019, 48, e27–e34. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.; Griffith, L.E.; Costa, A.P.; Leyenaar, M.S.; Agarwal, G. Community paramedicine: A systematic review of program descriptions and training. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 21, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, I.; Renner, W.; Schwarz, N. Der Fragebogen zu Teamwork und Patientensicherheit—FTPS (Safety Attitudes Questionnaire - deutsche Version). Prax. Klin Verhalt. Rehab. 2008, 79, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, J.B.; Helmreich, R.L.; Neilands, T.B.; Rowan, K.; Vella, K.; Boyden, J.; Roberts, P.R.; Thomas, E.J. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmreich, R.L.; Merritt, A.C.; Sherman, P.J.; Gregorich, S.E.; Wiener, E.L. The Flight Management Attitudes Questionnaire (FMAQ) (NASA/UT/FAA Technical Report 93-4); The University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

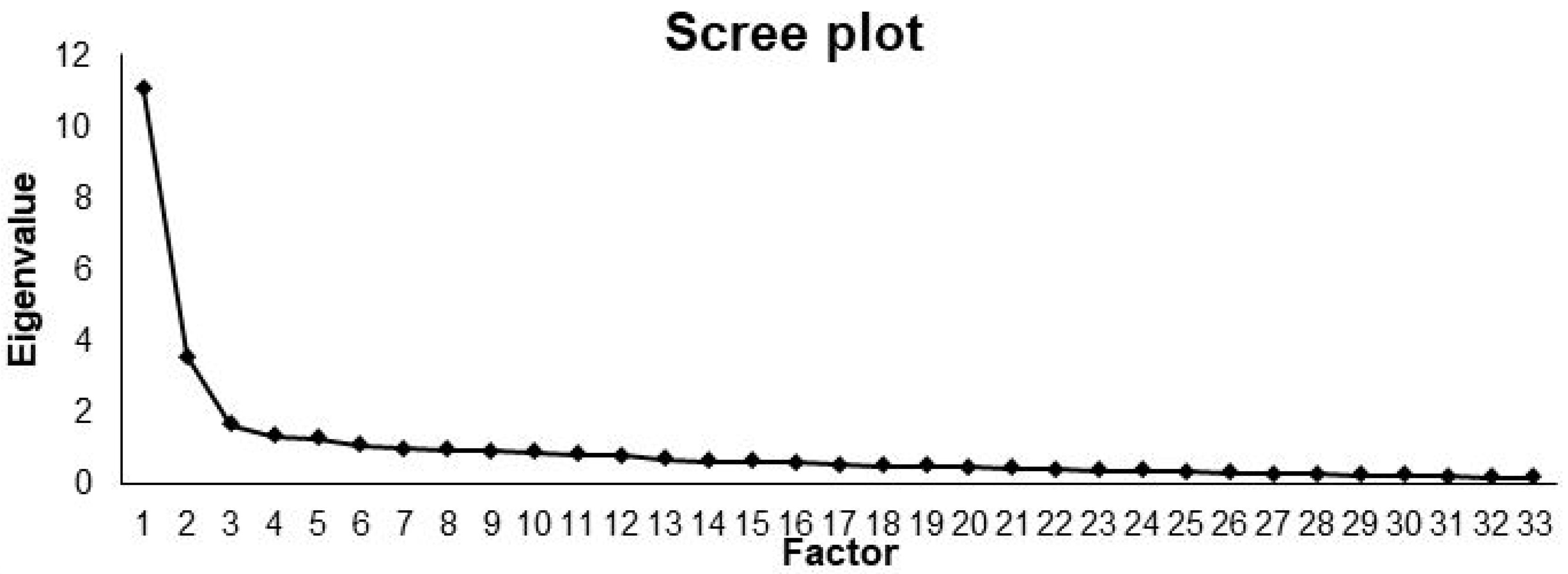

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, B.O.; Haugland, H.; Abrahamsen, H.B.; Bjørnsen, L.P.; Uleberg, O.; Krüger, A.J. Prehospital Stressors: A Cross-sectional Study of Norwegian Helicopter Emergency Medical Physicians. Air Med. J. 2020, 39, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- France, D.J.; Leming-Lee, S.; Jackson, T.; Feistritzer, N.R.; Higgins, M.S. An observational analysis of surgical team compliance with perioperative safety practices after crew resource management training. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 195, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leape, L.L. Error in medicine. JAMA 1994, 272, 1851–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzberg, M.; Rüsseler, M.; Egerth, M.; Doepfer, A.K.; Mutschler, M.; Stange, R.; Bouillon, B.; Kladny, B.; Hoffmann, R. Safety Culture in Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma Surgery—Where Are We Today? Z Orthop. Unfall. 2018, 156, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, M.; Brennan, P.A. What has an Airbus A380 Captain got to do with OMFS? Lessons from aviation to improve patient safety. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 57, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt-Bruce, S.D.; Hefner, J.L.; Mekhjian, H.; McAlearney, J.S.; Latimer, T.; Ellison, C.; McAlearney, A.S. What is the return on investment for implementation of a crew resource management program at an academic medical center? Am. J. Med. Qual. 2019, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doepfer, A.K.; Seemann, R.; Merschin, D.; Stange, R.; Egerth, M.; Münzberg, M.; Mutschler, M.; Bouillon, B.; Hoffmann, R. Safety culture in orthopedics and trauma surgery: Course concept: Interpersonal competence by the German Society for Orthopaedics and Trauma (DGOU) and Lufthansa Aviation Training. Ophthalmologe 2017, 114, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, K.; Langdalen, H.; Sollid, S.J.M.; Abrahamsen, E.B.; Sørskår, L.I.; Bondevik, G.T.; Abrahamsen, H.B. Training and assessment of non-technical skills in Norwegian helicopter emergency services: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2019, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurling, L.; Hedman, L.; Sandahl, C.; Felländer-Tsai, L.; Wallin, C.J. Systematic simulation-based team training in a Swedish intensive care unit: A diverse response among critical care professions. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.D.; Geis, G.L.; LeMaster, T.; Wears, R.L. Impact of multidisciplinary simulation-based training on patient safety in a paediatric emergency department. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, B.; Angele, M.K.; Jauch, K.W.; Kasparek, M.S.; Kreis, M.; Müller, M.H. Learning from aviation - how to increase patient safety in surgery. Zentralbl. Chir. 2012, 137, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Doekhie, K.D.; van Wijngaarden, J.D.H. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, W.; Davis, S.; Miller, K.; Hansen, H.; Sainfort, F.; Sweet, R. Didactic and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2011, 37, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.; Parand, A.; Soukup, T.; Reader, T.; Sevdalis, N. Aviation and healthcare: A comparative review with implications for patient safety. JRSM Open 2015, 7, 2054270415616548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, S.; Baxendale, B.; Buttery, A.; Miles, G.; Roe, B.; Browes, S. Implementing human factors in clinical practice. Emerg. Med. J. 2015, 32, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeppen, R.S.; Davidson, M.; Scrimgeour, D.S.; Rahimi, S.; Brennan, P.A. Human factors awareness and recognition during multidisciplinary team meetings. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2019, 48, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, B.; Rusin, L.; Kiesewetter, J.; Zottmann, J.M.; Fischer, M.R.; Prückner, S.; Zech, A. Crew resource management training in healthcare: A systematic review of intervention design, training conditions and evaluation. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catchpole, K.R.; Dale, T.J.; Hirst, D.G.; Smith, J.P.; Giddings, T.A. A multicenter trial of aviation-style training for surgical teams. J. Patient. Saf. 2010, 6, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höppchen, I.; Ullrich, C.; Wensing, M.; Poss-Doering, R.; Suda, A.J. Safety culture in orthopedics and trauma surgery: A qualitative study of the physicians’ perspective. Unfallchirurg 2021, 124, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| “TEAMWORK & PATIENT SAFETY” We ask you to fill out the questionnaire completely. The answer options are: - completely agree++ - agrees+ - neutral/ - rather does not agree -- - certainly does not agree - Please read each question (Q) carefully and then put a cross in the box that you think applies. Please tick the box that applies to you: Q1: Please check the box that applies to you: male __ female__ Q2: Please check the age box that applies to you: <35 years___/>35 years___ Q3: How long have you been in your professional medical practice outside of air ambulance service? <5 years___/5–10 years___/>5 years Q4: How long have you been involved in air rescue? <5 years___/5–10 years___/>5 years Q5: Please check the box that applies to you regarding your occupation in the hospital. | ||||||

| Surgeon | Nurse Specialist Anesthesiology | |||||

| Anesthesiologist | Intensive care nurse specialist | |||||

| Internal physician | Other service group | |||||

| Physician in other specialty | ||||||

| Q6: If you also work in ground-based rescue services, please tick the activity that applies to you. | ||||||

| Emergency Physician Ground-Based | ||||||

| Paramedic ground-based | ||||||

| Q | Questionnaire on Teamwork & Patient Safety | Agree Completely | Agree | Neutrally | Agree Rather Not | Agree Definitely Not |

| 7 | The skills I learned in air rescue through CRM and similar courses, such as communication skills, situational awareness, and the like, can also be used in my daily clinical work, and they have a positive impact on what I do there. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 8 | By applying air rescue skills to my day-to-day activities in the clinic, I feel more confident and satisfied than I would without such a background. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 9 | By transferring skills and structures that I use and experience in air rescue, patient safety can be improved in my hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 10 | By applying the skills acquired in air rescue, the cooperation between doctors, nurses and other professional groups can be improved in everyday hospital life. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 11 | Human Factors Training such as CRM and the skills that can be learned in it should be made available to all staff working in patient care at my hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 12 | If you also work in ground-based rescue services: The skills learned in airborne rescue service through trainings like CRM can also be used in my ground-based job and have a positive effect on it. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 13 | In my hospital, comments and suggestions that come from nurses are considered. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 14 | It is difficult in my department to raise concerns about nursing or medical treatment issues. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 15 | Decisions are made with the involvement of all those affected. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 16 | Doctors, nurses and other professionals are a well-coordinated team here. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 17 | Disagreements are resolved appropriately (not “who is right” but “what is the best solution for the patient”). | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 18 | I often cannot talk about discrepancies with the responsible doctors. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 19 | If you are not familiar with something, you can always ask questions about it. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 20 | I am supported by colleagues in the care/treatment of patients if I need help. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 21 | I know the first and last names of all the employees I was on duty with yesterday. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 22 | Important things are communicated reliably and understandably during the transfer of service. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 23 | Service handoff reports (to alert of potential hazards) are important for patient safety. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 24 | Meetings are held regularly at our hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 25 | I am satisfied with the cooperation between me and the doctors of this hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 26 | I am satisfied with the cooperation between me and the nursing staff of this hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 27 | Our staffing levels are always sufficient to provide good care for all patients. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 28 | I would feel well and safe as a patient in this hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 29 | Colleagues encourage me to report patient safety concerns. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 30 | Some employees more often disregard rules or guidelines that apply in their work area. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 31 | The atmosphere in this hospital helps individuals learn from the mistakes of others. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 32 | I get constructive feedback on my work performance. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 33 | Errors are dealt with appropriately in our hospital. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 34 | I would know who to contact with any concerns about patient safety. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 35 | It is difficult to talk about mistakes that have been made. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 36 | The management never knowingly compromises patient safety. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 37 | This hospital pays more attention to patient safety today than it did one year ago. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 38 | It is important to the management of the hospital that the highest attention is paid to patient safety. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| 39 | Suggestions that would help improve patient safety would be implemented by the management. | ++ | + | / | - | -- |

| Loading | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item (Q) | I. Cooperation | II. Human Factors | III. Communication | IV. Safety |

| Q13 | 0.83 | |||

| Q14 | −0.635 | |||

| Q15 | 0.73 | 0.312 | ||

| Q16 | 0.694 | |||

| Q17 | 0.665 | |||

| Q18 | −0.313 | |||

| Q19 | 0.518 | |||

| Q20 | 0.461 | |||

| Q25 | 0.499 | |||

| Q26 | 0.585 | |||

| Q28 | 0.481 | |||

| Q34 | 0.331 | |||

| Q7 | 0.82 | |||

| Q8 | 0.805 | |||

| Q9 | 0.814 | |||

| Q10 | 0.794 | |||

| Q11 | 0.623 | |||

| Q12 | 0.785 | |||

| Q23 | 0.106 | 0.141 | ||

| Q31 | 0.463 | 0.488 | ||

| Q21 | 0.302 | 0.500 | ||

| Q22 | 0.666 | |||

| Q24 | 0.326 | |||

| Q29 | 0.394 | 0.445 | ||

| Q32 | 0.303 | 0.579 | ||

| Q33 | 0.502 | 0.533 | ||

| Q35 | −0.429 | −0.451 | ||

| Q27 | 0.425 | 0.540 | ||

| Q30 | −0.307 | |||

| Q36 | 0.584 | |||

| Q37 | 0.794 | |||

| Q38 | 0.309 | 0.758 | ||

| Q39 | 0.385 | 0.604 | ||

| Item | Number (Percentage) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Gender | 199 male (79%) | 54 female (21%) | |

| Q2 Age | <35 years: 20 (8%) | >35 years: 233 (92%) | |

| Q3 How long have you been in your professional medical practice outside of air ambulance service? | <5 years: 2 (1%) | 5–10 years: 30 (12%) | >5 years: 221 (87%) |

| Q4 How long have you been involved in air rescue? | <5 years: 83 (33%) | 5–10 years: 71 (28%) | >5 years: 99 (39%) |

| Q5 Occupation in the hospital | |||

| Surgeon | 23 (9%) | ||

| Anesthesiologist | 185 (73%) | ||

| Internal physician | 6 (2%) | ||

| Physician in other specialty | 4 (1%) | ||

| Nurse specialist Anesthesiology | 16 (6%) | ||

| Intensive care nurse specialist | 19 (9%) | ||

| Q6 If you also work in ground-based rescue services, please tick the activity that applies to you. | |||

| Emergency physician ground-based | 174 (75%) | ||

| Paramedic ground-based | 59 (25%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Rüden, C.; Ewers, A.; Brand, A.; Hungerer, S.; Erichsen, C.J.; Dahlmann, P.; Werner, D. The Influence of Human Factors Training in Air Rescue Service on Patient Safety in Hospitals: Results of an Online Survey. Medicines 2023, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines10010002

von Rüden C, Ewers A, Brand A, Hungerer S, Erichsen CJ, Dahlmann P, Werner D. The Influence of Human Factors Training in Air Rescue Service on Patient Safety in Hospitals: Results of an Online Survey. Medicines. 2023; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines10010002

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Rüden, Christian, Andre Ewers, Andreas Brand, Sven Hungerer, Christoph J. Erichsen, Philipp Dahlmann, and Daniel Werner. 2023. "The Influence of Human Factors Training in Air Rescue Service on Patient Safety in Hospitals: Results of an Online Survey" Medicines 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines10010002

APA Stylevon Rüden, C., Ewers, A., Brand, A., Hungerer, S., Erichsen, C. J., Dahlmann, P., & Werner, D. (2023). The Influence of Human Factors Training in Air Rescue Service on Patient Safety in Hospitals: Results of an Online Survey. Medicines, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines10010002