Abstract

Background: The article examines the adoption of competitive intelligence (CI) in Ghana’s humanitarian sector, identifying barriers such as resource limitations and organizational challenges, while highlighting CI’s potential to enhance decision-making, partnerships, and efficiency. Methods: The study adopted a mixed-method research approach. Survey questionnaires and interviews were conducted with 34 humanitarian organisations in Ghana as part of the study. Results: The study established that, few humanitarian organisations in Ghana are practising CI. Many organisations have no established and specific procedures and staff for CI. The main challenges organisations experience when implementing CI include limited resources, especially in funding, lack of skilled workforce, and limited technological support. Other challenges include the organisational culture, lack of support from organisational leadership, and competing priorities. However, the study re-vealed the benefits and opportunities of CI for Ghana’s humanitarian sector, which include better decision-making and resource utilisation, cooperation and partnerships, flexibility and prepared-ness, and organisational efficiency and outcomes. Conclusion: The study concluded that the human-itarian organisations in Ghana will need to address the challenges mentioned above and build on those opportunities to harness the potential of CI effectively. Some suggestions include the sensitisation of CI, resource mobilisation, capacity development, culture change, and CI institutionalisation.

1. Introduction

The non-governmental organisations functioning in the territory of Ghana work under challenging conditions since they have to help vulnerable groups of the population in various crises, including natural disasters, health cataclysms, and socio-economic problems [1,2,3]. As international issues continue to soar and resources dwindle, these organisations have no option but to adapt and try new methods to provide the best aid [4]. CI has been acknowledged as an asset for humanitarian organisations, helping them navigate this environment and make positive decisions to enhance organisational performance [5].

It systematically gathers, analyses, and disseminates environmental information to enable strategic planning [6,7]. While business has been associated with corporate intelligence, its usage has spread to the humanitarian field, where organisations aim to identify beneficiaries’ needs, assess the effectiveness of the service provision, use funds effectively and efficiently, and cooperate with other stakeholders [8]. Based on CI, humanitarian agencies can detect shifting community needs, estimate future challenges, and adapt procedures.

Recent investigations revealed that CI can revolutionise humanitarian aid. For instance, Subbarao [9] and Zwitter [10] highlight the challenges of competition, which can compromise the delivery and quality of services and the effectiveness of operations. In the same regard, Kim and Menninga [11] and Monaghan and Lycett [12] examine the impact of competition on aid allocations and the potential of big data to improve humanitarian supply networks.

In addition, CI can improve cooperation and information exchange within humanitarian organisations. Promoting the communication of knowledge and team learning is an effective method of avoiding replication in an organisation. It also helps one to search for successful solutions and find new approaches to complex issues [13]. This type of CI is crucial in humanitarian aid situations where organisations may encounter challenges and sometimes share objectives.

However, bringing CI to Ghana’s humanitarian context comes with factors such as data ethics, data privacy and protection for vulnerable groups, and political and cultural concerns in the country [14,15,16]. In addition, the current capacity of humanitarian organisations in Ghana may be limited by inadequate resources, technical know-how, and awareness of the value of CI to enable them to harness CI tools and methodologies effectively.

Although there is recognition of the contribution of CI to the humanitarian sector, there is still room to understand how CI can be used effectively in the Ghanaian context. Other research works have also attempted to examine the CI in other African nations [8], but few studies have focused on Ghana. This lack of context-specific knowledge hinders Ghanaian humanitarian organisations from developing CI strategies to make them understand the possible benefits of the CI approach.

To fill this gap and strengthen CI for humanitarian operations in Ghana, this study explores the opportunities and constraints of CI in Ghana. This entails discovering the extent to which Ghanaian humanitarian organisations have embraced CI currently, the challenges that make it difficult for them to adopt CI, and the possible benefits and opportunities associated with CI. As such, future studies will help Ghanaian humanitarian organisations to derive the maximum benefits of CI to improve their effectiveness and meet the needs of vulnerable communities. The study sought to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: What is the current state of CI adoption among Ghanaian humanitarian organisations?

- RQ2: What are the barriers to adopting CI in Ghana’s humanitarian sector?

- RQ3: What are CI’s potential benefits and opportunities for Ghana’s humanitarian sector?

The main contributions of this research are threefold. In practice, this study can contribute to the understanding of Ghanaian humanitarian organisations on how CI can increase their influence and success. By determining the lessons learned, cases and examples of the approaches used to advance CI in the context of the lack of resources and local conditions, the study can provide practitioners with strategies for enhancing the decision-making mechanisms, resource management, and cooperation among the humanitarian actors. This, in turn, may increase the overall aid effectiveness and positively impact the vulnerable groups served.

From a policy perspective, the findings of this research hope to contribute to the formulation of policy and guidelines, framework, and assistance to support the implementation and integration of CI in the Ghanaian humanitarian sector.

Last but not least, this study is essential for future research on humanitarian aid and competitive intelligence. In doing so, the study opens the door to future research examining the concrete experiences of CI in Ghana and other developing nations. It is helpful to note that the presented results can be used as the research basis for future investigations and can encourage scholars to search for fresh ways, methods, and theories that would help to develop CI’s potential to support humanitarian activities.

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review covering the theoretical foundations, an overview of the humanitarian sector in Ghana, empirical findings on awareness and adoption of CI, barriers to CI adoption and benefits and opportunities of CI in the humanitarian sector. Section 3 describes the materials and methods used in this study. Section 4 presents the results of the study. Section 5 discusses the findings and presents the study’s limitations and suggestions for future research directions in the field of CI in the humanitarian context. Finally, Section 6 concludes the article by summarising the essential findings and providing recommendations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Review

Resource-Based View (RBV) Theory

Resource-Based View (RBV) theory is one of the most prominent theories in strategic management [17,18]. According to the VRIO framework, a firm’s competitive advantage arises from the valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources and capabilities the firm possesses [17]. These resources can be physical, for example, capital and plant assets, and inalienable, including an organisation’s knowledge, reputation, and culture [18].

RBV theory asserts that resources are heterogeneous in firms, and the differences in resource possession may be immovable [17,18,19,20]. This heterogeneity enables certain firms to outcompete others and record high performance by leveraging their resource bundles [21]. However, not all resources are strategically relevant. Resources valuable in terms of exploiting opportunities or neutralising threats, scarce in the industry, hard to imitate, and not easily substitutable are considered to bestow a sustainable competitive advantage [17].

RBV theory is highly relevant for strategy formulation and implementation. It highlights the need to define, nurture, and exploit the resources and capabilities that set a firm apart from its competitors [22]. Organisations should strive to develop and maintain their valuable, rare, and inimical resources while simultaneously investing in new competencies [23]. In addition, RBV theory has noted that resource-based tactics like diversification, vertical integration, and strategic partnerships could further improve a firm’s resource standpoint and competitive position [24].

Even though RBV theory has gained considerable attention in strategic management, it has not been without criticism. Critics of the theory have contended that the theory is tautological and possesses no empirical measurability [25]. Some scholars argue that the theory focuses too much on the internal environment and disregards the firm’s external environment, including industry forces and structures [26].

RBV theory can be helpful for this research in developing an understanding how Ghanaian humanitarian organisations can transform their internal resources, like knowledge, skills, and relationships, to build effective CI strategies. By developing these specific assets, organisations can improve their capabilities for acquiring, processing, and applying competitive intelligence for management and organisational performance enhancement.

2.2. Competitive Intelligence (CI)

CI has become an important concept that helps organisations obtain a competitive edge in the modern and somewhat volatile world. In simple terms, CI is the process of gathering, analysing, and disseminating information about competitors, customers and the business environment to facilitate decision-making and improve organisational performance [27,28]. CI transcends information collection to encompass the processing of information in the form of intelligence that can be applied in strategy development, market positioning and resource mobilisation [29,30].

The CI process generally comprises the following steps. First, organisations need to determine their intelligence requirements and set the boundaries of CI operations [31]. This includes identifying the key information needs of decision-makers and ensuring that CI initiatives support organisational goals. Secondly, appropriate data and information are gathered from primary sources such as interviews, surveys, and secondary sources such as public databases and industry reports [32] (p. 337). Thirdly, the collected data are then used to develop insights with the help of tools such as SWOT analysis, scenario planning, and competitor profiling [33]. Finally, insights are shared with decision-makers through reports, dashboards, or briefings, improving their decision-making [34].

Consequently, the adoption of CI has various advantages for organisations. By enhancing the firms’ understanding of the competition, CI enables future trends to be predicted, threats and opportunities to be seen, and further strategies to be adjusted [35,36,37]. CI also reduces uncertainty and improves the quality of information available to decision-makers to help them make better decisions [37]. Furthermore, CI can help design new products that meet customers’ needs, which they are unaware of [38]. Research evidence supports the notion that CI results in enhanced organisational performance in terms of improved market share, profitability, and competitive advantage [39,40].

However, the advantages of CI outweigh the costs for organisations aspiring to compete effectively within their respective markets. With CI as a strategic management tool, organisations can improve their chances of predicting market conditions and trends, identifying opportunities and threats, and making better business decisions. Thus, CI will remain a relevant and valuable asset as the business environment enters a new stage, and it will remain a vital tool for companies that seek to thrive in today’s global environment.

2.3. Humanitarian Sector in Ghana

The humanitarian sector in Ghana is responsive to the different social and economic development challenges and offers services to needy and vulnerable persons in the society. These problems include poverty, food insecurity, health challenges, disasters, and conflicts, and humanitarian organisations must address these issues in countries like Ghana and other developing nations [41,42,43]. The major players in the humanitarian system in Ghana are the INGOs, local NGOs, the government, and CBOs [1,43].

The humanitarian space in Ghana has developed over time, and the country now focuses more on preparedness, response, and recovery. Contemporary interventions have evolved from primarily focusing on providing immediate assistance to addressing durable causes of susceptibility [1]. This change has been due to the realisation that mere humanitarian aid is insufficient to bring about sustainable change and that addressing the needs of the affected population requires a comprehensive approach [44]. Therefore, Ghana’s humanitarian organisations have implemented measures focusing on response, rehabilitation, and reconstruction initiatives [1].

Stakeholders in the humanitarian aid sector involve UN agencies, including UNICEF, UNDP, WFP, ICRC, and INGOs, including OXFAM, SAVetheChildrens, and WORLD VISION, among others [45]. These organisations contribute essential resources, knowledge, and connections to help humanitarian causes in the country. However, they also face difficulties localising their interventions and making them sustainable [1].

Local NGOs and CBOs also operate in Ghana’s humanitarian system. These organisations understand the cultures and peculiarities of the targeted communities and their needs [1]. They always serve as implementing partners for international organisations and give great information about local contexts [46]. Nevertheless, local NGOs and CBOs are subjected to resource limitations and capacity constraints that hinder them from expanding their impact [1].

Another important stakeholder in the humanitarian sector of Ghana is the government, represented by different ministries and departments. The government determines policies, manages aid, and distributes resources and services to needy groups [47]. Nonetheless, the government is usually faced with scarce resources and various structural impediments that adequately hinder its ability to address humanitarian crises [2].

Various actors are involved in humanitarian action in Ghana, and cooperation between them is crucial. Some of the available platforms include the Ghana Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), through which stakeholders gain knowledge, harmonise their operations, and formulate collective strategies [48]. However, challenges include competition for resources, duplication of efforts, and a lack of trust that may affect collaboration [1].

2.4. Awareness and Adoption of Competitive Intelligence (CI)

Several empirical studies have explored the awareness and adoption of competitive intelligence (CI) practices across various sectors [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Nenzhelele [49] conducted a quantitative study to determine how much CI is practised within South Africa’s property sector. Data were collected using a web-based questionnaire administered to estate agencies, and the findings revealed that the industry is highly competitive. Estate agencies utilise CI practices to gain a competitive advantage and support decision-making. Moreover, it was found that CI in this sector is carried out legally and ethically.

Similarly, Nasri [50] investigated the level of knowledge regarding CI among Tunisian companies. This exploratory study employed semi-in-depth interviews and focus groups with six executives from companies operating in three sectors: communication technologies, manufacturing, and commercial retailing. The results indicated that Tunisian managers are aware of the importance of CI in managing their companies.

Further contributing to the discourse, Priporas [51] examined CI use in the liquor retail sector in the USA. The study employed an exploratory single longitudinal case study using observation, semi-structured interviews, and secondary document analysis over two phases. Despite the company’s small size, content analysis revealed that the owner actively monitored competition using various information sources, converting this into intelligence for short-term and long-term strategic decisions.

Tsokanas and Fragouli [52] explored the awareness and presence of CI in the Greek pharmaceutical industry. The study employed a feasibility study that combined interviews, online surveys, industry analysis using Porter’s (1980) five forces model, and a comprehensive literature review. Although the awareness of CI within the Greek pharmaceutical industry was high, actual knowledge of CI was relatively low, with no formal CI process in place. The study suggested that a CI process could be beneficial if implemented.

Similarly, Bulley et al. [53] aimed to understand the role, sophistication, and intensity of CI processes in an organisation. This exploratory study employed a triangulation approach, incorporating a survey and interviews with 15 personnel. The findings indicated that while the organisation recognised the importance of CI, it had yet to utilise its potential fully. Furthermore, the study found that CI practices were conducted on an ad hoc basis rather than through a formalised process.

Lastly, Murege [54] investigated the extent to which mobile phone service companies in Kenya use CI as a strategic tool. A survey research design was employed, with data collected via a self-administered questionnaire distributed to all four mobile phone service providers in Kenya. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data, revealing that these companies use CI to develop strategies that enhance their competitiveness.

These studies highlight the growing awareness and varied adoption of CI practices across different sectors and regions, with some industries demonstrating higher levels of integration and formalisation of CI processes than others.

2.5. Barriers to Adoption of Competitive Intelligence (CI)

A limited number of empirical studies have addressed the complexities and challenges of adopting CI in different organisations [55,56,57,58] (April and Bessa, 2006; Priporas et al., 2005; Garcia-Alsina et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2013).

April and Bessa [55] contributed to the literature by analysing two CI processes within a global energy multinational: competitive strategic business intelligence (CIAD) and competitive technical intelligence (CTI). Their study revealed that organisational culture, which discourages open knowledge sharing, was a significant barrier to successfully adopting CI practices by the company.

Priporas et al. [56] explored the obstacles to CI adoption in Greek companies. In-depth interviews were conducted with representatives from 50 well-known companies in Thessaloniki. The findings highlight several key reasons for the slow adoption of CI, including a general lack of awareness, insufficiently skilled staff, a shortage of experts to provide training, high perceived costs, and satisfaction with existing market research activities conducted by in-house marketing departments.

In a related study, Garcia-Alsina et al. [57] examined the factors inhibiting the effectiveness of CI practices at Spanish universities. Using a mixed-methods approach, the researchers conducted face-to-face, semi-structured interviews with 47 university managers, including degree coordinators, deans, and vice-rectors. This was followed by a questionnaire administered to 400 degree coordinators and deans. The study identified several inhibitor factors, such as regulatory constraints, organisational challenges, pressure, uncertainty, and a predominance of barriers, which significantly affected the efficacy of CI practices in this academic context.

Similarly, Wright et al. [58] focused on identifying the barriers to higher-level CI adoption among SMEs in Turkey. Data were collected using a robust questionnaire, revealing that outdated, misleading, or hard-to-find data, inadequate financial resources, a lack of CI expertise, managerial ignorance, and insufficient organisational learning were significant hindrances to implementing CI in these enterprises.

These studies collectively suggest that barriers to CI adoption are multifaceted, ranging from resource constraints and lack of expertise to cultural and organisational factors, which complicate the implementation of CI across various sectors.

2.6. Benefits and Opportunities of Competitive Intelligence (CI)

Competitive intelligence (CI) offers numerous benefits and opportunities for organisations, as highlighted in several empirical studies [59,60,61,62,63,64]. Olszak et al. [59] conducted a study to investigate the key advantages organisations can derive from using CI. Surveys were administered across 233 organisations, and the findings indicated that CI enhances organisational effectiveness in monitoring their environments, enables faster identification of market opportunities and threats, deepens the understanding of customers and their preferences, and improves decision-making across all management levels.

Similarly, Placer-Maruri et al. [60] analysed the impact of CI on various financial and non-financial variables in SMEs. The study collected data via questionnaires and conducted statistical analysis using ANOVA models following a quantitative empirical methodology. The results suggest that CI significantly enhances SMEs’ ability to adapt to environmental changes, boosts innovation capabilities, and supports value creation within their business operations.

In a related study, Supardi and Setiahati [61] explored the potential application of CI in educational institutions. Through an extensive literature review, they concluded that CI can improve institutional performance, foster knowledge-sharing practices, and stimulate organisational innovation, all of which contribute to achieving sustainable competitive advantage within the education sector.

Viviers and Muller [62] extended the discussion by examining CI’s role in improving South African companies’ competitiveness. Their empirical research demonstrated that CI is recognised as a critical business function, with South African companies acknowledging its role in enhancing competitiveness at the organisational and national levels.

Furthering this perspective, Agarwal [63] explored the relationship between CI and organisational knowledge management systems. The study found that CI is pivotal in converting raw data into valuable insights, which can inform strategy and translate into actionable decisions. This process is essential to maintaining an organisational advantage and improving overall business performance.

Lastly, Nasri [64] conducted an extensive literature review to explain the common processes used to develop and maintain competitive intelligence systems in organisations. The study highlighted that organisations focused on building robust CI systems are better positioned to gain a sustainable competitive advantage.

2.7. Research Gaps and Innovations

Most of the empirical studies focus on CI in business contexts. There is a lack of research examining CI practices, challenges, and benefits in humanitarian organisations. Most studies are conducted in developed countries or different African nations. There is a notable absence of research on CI in Ghana’s humanitarian sector. Moreover, existing research on competitive intelligence (CI) primarily employs single-method approaches, often focusing on quantitative or qualitative surveys. There is a notable absence of mixed-methods studies, particularly in the humanitarian sector. Hence, the present study combines quantitative surveys with in-depth qualitative interviews to comprehensively understand CI adoption, barriers, and benefits in Ghana’s humanitarian sector.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Description

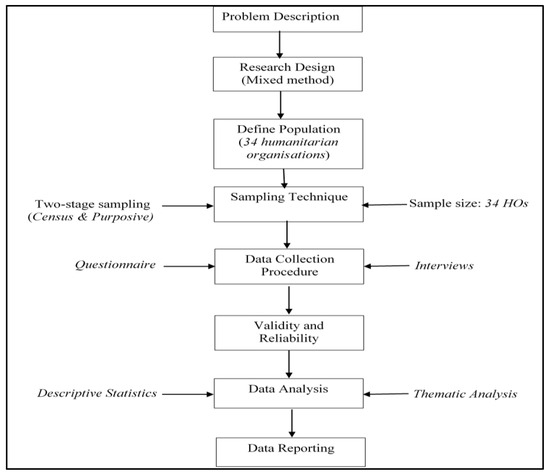

Humanitarian organisations in Ghana face many challenges in their efforts to provide effective aid and support to vulnerable populations. These organisations operate in a complex and dynamic environment characterised by limited resources, the changing needs of beneficiaries, and increasing competition for funding. As the humanitarian landscape evolves, there is a growing need for these organisations to adapt their strategies, optimise resource allocation, and enhance their overall effectiveness. The methodology flow chart is shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

Methodology Flow Chart.

3.2. Research Design

A mixed-method research design was adopted for this study. This approach combines quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem [65].

The quantitative aspect of the study entailed collecting numerical data through a survey of Ghanaian humanitarian organisations to determine the awareness and adoption of CI and the barriers and benefits of adopting CI. This provided a broad overview of the research problem and allowed for statistical analysis and generalisation [66].

The qualitative aspect entailed collecting textual data through interviews with participants chosen for the study. This gave a detailed understanding of the experiences, opportunities, and challenges concerning the adoption of CI [67].

This choice of a mixed-method design had the potential to provide a richer and more detailed understanding of the research questions and the strengths of each approach, complementing the limitations of the other [68]. Moreover, the choice of the mixed-methods design was informed by a Garcia-Alsina et al. [57] study, which used this design in the similar context of CI at universities, demonstrating its suitability for addressing the research objectives and questions.

3.3. Study Population

The study population comprises humanitarian organisations operating in Ghana as per the Logistics Capacity Assessment (LCA) [69]. This population entails various forms of organisations involved in humanitarian operations, including international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), local non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and community-based organisations (CBOs). According to the Logistics Capacity Assessment (LCA) [69] data, 34 humanitarian organisations operate in Ghana.

3.4. Sampling Technique and Sample Size

A two-stage sampling technique, specifically the census and purposive sampling techniques, was adopted for this study. Census sampling involves collecting data from every targeted population member [66]. This approach ensures that all population cases are included in the analysis and there is no sampling bias, which is crucial, especially when working with small populations [70]. Hence, for the 34 humanitarian organisations in Ghana [69], a census sampling technique was considered appropriate for the present study due to the small population size.

For the quantitative part of the research, a census survey was conducted among all 34 humanitarian organisations. On the other hand, in the qualitative aspect of the study, the researchers used the purposive sampling method to select 34 personnel from each organisation. They held positions such as executive directors/CEOs, programme managers, monitoring and evaluation officers, and project coordinators. The purposive sampling enabled the researcher to select rich, informative cases that offered comprehensive information about the research question [71]. A sample size of 10–15 participants is recommended for qualitative interviews, as this range is considered sufficient for reaching data saturation in most cases [72]. According to Guest et al. [72]’s recommendation, a sample size of 10 participants was chosen for the study.

3.5. Data Collection Procedure

The data collection procedure for this mixed-methods study involved two main phases: a quantitative phase using a survey questionnaire and a qualitative phase using interviews.

For the quantitative part of this study, a survey questionnaire was distributed to all 34 humanitarian organisations in Ghana via their company emails. The survey was conducted through Google Forms, and a link to the survey was forwarded to the contact person of every organisation. The survey comprised closed questions to determine the awareness and adoption of CI, barriers to adoption, and perceived benefits and opportunities [67]. To increase the response rate, follow-up emails and phone calls were directed to the sample group, as suggested by Dillman et al. [73].

For the qualitative phase, interviews were conducted with ten (10) purposively selected participants from 34 organisations. The interviews were conducted using video conferencing software, Zoom and Google Meet, depending on the participants’ preferences and convenience. An interview guide was developed to ensure consistency across interviews while allowing for flexibility to explore emerging themes [65]. The interviews were conducted in English, and the participants were asked to sign a consent form allowing the use of the recorded data in the study [65].

3.6. Research Instrument

3.6.1. Online Survey

The online survey was developed using Google Forms, which is known for its features, such as providing a platform for complex survey designs and data security [66]. The survey is structured into four sections (see Appendix A). The survey begins with a demographics section, which solicits information about the respondents, such as the name of the organisation, type of organisation, number of years of operating in Ghana, and the number of employees and their positions within the organisation.

The second section focused on the awareness and adoption of CI, comprising five statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale. This section was crucial for identifying the level of awareness and adoption of CI by humanitarian organisations in Ghana.

The third section delved into the barriers to CI adoption. Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they agree to five itemised statements on a 5-point Likert scale. This section was crucial for identifying the most significant barriers hindering the adoption of CI by humanitarian organisations.

The final section of the survey focused on the benefits and opportunities of CI adoption. Similarly to the previous sections, it comprised questions asking respondents to rate the extent to which they agree to five itemised questions on a 5-point Likert scale. This section was crucial for identifying the most significant benefits of CI to humanitarian organisations in Ghana.

3.6.2. Interview Guide

The semi-structured interview guide consists of 10 open-ended questions designed to gather in-depth qualitative data on competitive intelligence (CI) adoption among humanitarian organisations in Ghana (see Appendix B). The semi-structured nature of these questions allowed for flexibility, enabling the interviewer to probe deeper into responses and explore emerging themes. This approach helped gather rich, context-specific data that complements the quantitative survey data, providing a more comprehensive understanding of CI adoption and the related barriers and opportunities in Ghana’s humanitarian sector.

3.7. Validity and Reliability

Validity, which refers to measurement accuracy, and reliability, which concerns the consistency of measurements, were achieved through several methodological approaches [74]. Content validity was established through a comprehensive literature review and expert consultation [75]. The survey items were adapted from empirical studies on CI and modified to suit the context of humanitarian organisations in Ghana. A panel of CI and humanitarian-sector experts reviewed the instrument, providing feedback on the relevance and clarity of the items, which were then refined accordingly [76]. Construct validity was addressed through pilot testing with a small sample of humanitarian organisations similar to the target population [77].

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for multi-item scales within the survey to enhance reliability, particularly for the CI adoption, barriers, and benefits sections [78]. Table 1 below presents the Cronbach alpha value for the variables employed.

Table 1.

Reliability Analysis.

Items on a questionnaire are considered statistically reliable if the Cronbach alpha values are higher than 0.7. Table 1 shows a Cronbach alpha value of 0.85 for the Awareness and Adoption of CI scale, indicating good internal consistency. This value surpasses the standard alpha of 0.70, suggesting that the items in this scale are reliable and consistently measure the construct of CI awareness and adoption among humanitarian organisations in Ghana.

The Cronbach alpha value of 0.83 for the Barriers to Adopting CI scale also demonstrates strong internal consistency, well above the standard alpha of 0.70. This suggests that the scale is reliable for measuring the challenges faced by humanitarian organisations in implementing CI.

Finally, the Benefits and Opportunities of CI scale shows excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha value of 0.88, indicating that the items reliably measure the perceived advantages of CI adoption in the humanitarian sector.

For the interviews, validity and reliability were ensured through intercoder reliability. Intercoder reliability (ICR) is a crucial measure of agreement among multiple coders analysing qualitative data, enhancing the trustworthiness and the validity of research findings [79]. The researchers coded the data and compared their coding to reach a consensus. Moreover, member checking was conducted by sharing interview transcripts or summaries with participants to verify the accuracy of their statements and interpretations. This allowed participants to clarify and ensure the validity of their responses.

3.8. Data Analysis

The data analysis for this mixed-methods study involved separate quantitative and qualitative data analyses, followed by integrating the findings to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem [65]. Descriptive statistics was performed for the quantitative data using SPSS. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages, and means, were determined to explain the data on the awareness and adoption of CI adoption, barriers to adoption, and perceived benefits and opportunities.

For the qualitative data, the thematic analysis method was used [71]. The interview transcripts were analysed, and themes and codes were identified using NVivo software. The coding process involved inductive coding, enabling new codes to be developed [80]. The coded data were organised into themes to comprehensively understand the experiences, challenges, and perceptions of CI adoption in the Ghanaian humanitarian sector [67].

3.9. Ethical Considerations

When carrying out the study, the following ethical issues were considered to ensure the participants’ welfare and maintain the integrity of the research. The participants’ informed consent was acquired before the study, and the study’s objectives, methods, and possible consequences were explained and understood. This process was entirely voluntary, and nobody was forced or pressured to continue with the study if they did not wish to do so. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, the responses given by the participants were kept confidential and could only be accessed by the research team. The researchers evaluated and controlled the psychological harm to participants and their possible adverse reactions. They were informed of the handling and sharing of their data, and the researchers respected the data by using them in the manner agreed upon in the informed consent form. The researchers ensured that the participants’ rights were respected, potential harm was minimised, and the research adhered to high ethical standards.

4. Results

This section presents the research findings and discusses them in the context of the existing literature.

4.1. Demographic Information

Table 2 shows the demographic information of the respondents from 34 humanitarian organisations who participated in the survey.

Table 2.

Demographic Information.

Table 2 shows that most participants were from local NGOs (44.1%), while 35.3% were from international NGOs, 17.6% were from community-based organisations, and the rest were from other organisations (2.9%). This distribution means that the study gathered information from various humanitarian actors working in Ghana.

Regarding the duration of their operations in Ghana, 41.2% have been active for 5–10 years, 26.5% for 11–20 years, 20.5% for less than 5 years, and 11.8% for more than 20 years. This implies the study involved experienced organisations operating in the Ghanaian humanitarian sector for many years and relatively few new organisations.

Regarding the numbers of employees, the organisations’ sizes vary. Of the respondents, 52.9% are employed in organisations with 10–50 employees, 20.6% have between 51 and 100 employees, 14.7% have less than 10 employees, and 11. 8% have more than 100 employees. This indicates that the study included small and large humanitarian organisations, thus making the findings generalisable.

The respondents occupy various levels in the organisational hierarchy, with the largest group of the respondents being programme managers (35.3%), while the rest are monitoring and evaluation officers (23.5%), executive directors/CEOs (17.6%), project coordinators (14. 7%), and 8.8% hold other positions. This distribution enabled the capture of the views of people engaged in humanitarian work at various levels, from policymaking to planning, implementing, and evaluating the programmes.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.2.1. The Current State of CI Adoption Among Ghanaian Humanitarian Organisations

Table 3 presents findings on the current state of CI adoption among Ghanaian humanitarian organisations. Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements on the awareness and adoption of CI in their organisations.

Table 3.

Current state of CI adoption among Ghanaian humanitarian organisations.

The statement with the highest mean score of 3.62 is “Competitive Intelligence (CI) is known to our organisation”. A total of 64.7% of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, suggesting that most Ghanaian humanitarian organisations are moderately aware of CI. However, 17.7% of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that there is potential for improving the organisational awareness of CI among some firms.

The second-highest ranked statements received a mean score of 3.18 each; these being “Our organisation currently employs CI practices” and “Our organisation uses CI for strategic decision-making”. Of the respondents, 44.2% agreed or strongly agreed with both statements, suggesting that many humanitarian organisations in Ghana practice CI and consider insights from CI when making strategic management decisions. However, 29.4% of the participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with the first statement, and 29.4% stated either ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ with the second. This indicates that there is still room for organisational improvement in CI adoption and implementation.

The fourth-ranked statement, with a mean score of 2.71, is “Our organisation have a formal CI process in place”. 44.1% of the respondents disagreed with or strongly disagreed with this statement, while 23.5% agreed or strongly agreed. This implies that many of the humanitarian organisations in Ghana have informal and uncoordinated ways of undertaking CI activities.

The lowest-ranked statement, with a mean score of 2.44, is “Our organisation has a dedicated CI unit or personnel”. 58.8% of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement, while only 20.6% agreed or strongly agreed. This suggests that most Ghanaian humanitarian organisations do not have specialised staff or departments responsible for CI, which may hinder the implementation and management of CI initiatives.

4.2.2. Barriers to CI Adoption

Table 4 presents findings on barriers to CI adoption among Ghanaian humanitarian organisations, where respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements on barriers to CI adoption in their organisations.

Table 4.

Barriers to CI Adoption.

The most significant barrier to CI adoption is the lack of financial resources, with a mean score of 3.91. A total of 73.6% of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that financial constraints hinder their organisations’ ability to implement CI practices. This finding suggests that many Ghanaian humanitarian organisations struggle to allocate sufficient funds for CI initiatives.

The second most important barrier is the lack of technological infrastructure, with a mean score of 3.65. A combined 64.7% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that inadequate technological resources impede CI adoption. This highlights the need for organisations to invest in the necessary tools and systems to support CI activities.

A lack of skilled personnel ranks as the third most significant barrier, with a mean score of 3.62. A total of 61.7% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that lacking employees with the required skills and knowledge hinders CI implementation. This underscores the importance of training and capacity building to develop CI competencies within humanitarian organisations.

Organisational culture and resistance to change rank fourth, with a mean score of 3.26. While 47.1% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that these factors pose a challenge, the lower mean score suggests that cultural and attitudinal barriers may be less prominent than resource-related constraints.

Legal and ethical concerns rank as the least significant barrier, with a mean score of 2.91. Only 29.4% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that these issues hinder CI adoption. This finding indicates that, while legal and ethical considerations are important, they may not be perceived as a significant obstacle by most Ghanaian humanitarian organisations.

4.2.3. Benefits and Opportunities of CI

Table 5 presents findings on the benefits and opportunities of CI adoption to Ghanaian humanitarian organisations. Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements on barriers to CI adoption in their organisations.

Table 5.

Benefits and Opportunities of CI.

The statement with the highest mean score of 4.03 is “CI can contribute to our organisation’s overall effectiveness and impact”. In total, 82.4% of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, indicating that most Ghanaian humanitarian organisations perceive CI as a valuable tool for enhancing their organisational performance and achieving their mission objectives.

The second-highest ranked statement, with a mean score of 4.00, is “CI can help our organisation adapt to the changing needs of beneficiaries and the humanitarian landscape”. A combined 76.5% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, suggesting that CI is a crucial means of staying responsive to the evolving needs of the communities they serve and navigating the dynamic humanitarian context.

The third-ranked statement, with a mean score of 3.91, is “CI can improve our organisation’s resource allocation and management”. A total of 73.6% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, indicating that CI is perceived as a valuable tool for optimising the use of limited resources and ensuring their effective deployment in humanitarian operations.

The fourth- and fifth-ranked statements, with a mean score of 3.88, are “CI can enhance our organisation’s decision-making capabilities” and “CI can help our organisation identify new opportunities for collaboration and partnerships”. For both statements, over 70% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed, highlighting the potential of CI to support informed decision-making and foster strategic partnerships within the humanitarian sector.

4.3. Thematic Analysis

4.3.1. The Current State of CI Adoption Among Ghanaian Humanitarian Organisations

Based on the thematic analysis, two final themes emerge regarding the current state of CI adoption among Ghanaian humanitarian organisations, shown in Table 6 below:

Table 6.

Thematic analysis of the current state of CI adoption.

Low Level of CI Awareness and Understanding

Most participants responded that their organisations are aware of CI but not well informed on how it can benefit their organisation, given its specific environment. For instance, based on the data from P1, he said, “There is awareness about CI requirement in our organisation, but it is not optimised”. Similarly, P5 stated, “Our organisation knows about CI but does not know how to use it fully”. P7 echoed the response of P1 and P5 by saying, “We are not very knowledgeable about CI, and we have not ventured far into using it”.

Absence of Formal CI Practices

According to the results, most participants confirmed that their organisations lack an established CI practice. However, they obtain information from informal channels and, occasionally, uncoordinated attempts to gather data on the sector and stakeholders. For example, P3 noted, “We do not use any systematic CI, but we garner information informally”. P6 also stated, “We collect information on the humanitarian sector and our stakeholders but not formally”. P9 also stated, “We do not have any CI practices, but we gather information through word of mouth”.

4.3.2. Barriers to Adopting CI in Ghana’s Humanitarian Sector

Based on the thematic analysis, three final themes emerge regarding the barriers to adopting CI in Ghana’s humanitarian sector, shown in Table 7 below:

Table 7.

Thematic analysis of barriers to CI adoption.

Inadequate Resources

Participants also said that lacks of funds, staff who would focus on CI, and technical facilities were key issues hindering CI use. For instance, Participant 1 said, “The main difficulties are resource constraints and lack of qualified staff for CI”, and Participant 3 added, “Lack of financial resources, technology support, and skilled employees”.

Organisational Culture and Leadership

Some participants mentioned barriers including a lack of culture change, top management support, and competing priorities. Participant 4 said, “The major challenges include inadequate financial resources, competing priorities, and lack of leadership support”. Participant 7 supported this, saying, “The biggest challenges include lack of financial resources, competition from other initiatives, and lack of top management support”.

Low Awareness and Understanding of CI

One of the participants pointed out the lack of knowledge about the advantages of CI as a barrier, which relates to the previously discussed theme of poor CI awareness. Participant 2 said, “The key constraint is a shortage of resources, which includes money and people, and CI is not well understood”.

4.3.3. Benefits and Opportunities of CI for the Humanitarian Sector of Ghana

Based on the thematic analysis, four final themes emerge regarding CI’s potential benefits and opportunities for Ghana’s humanitarian industry in Table 8 below:

Table 8.

Thematic analysis of benefits and opportunities of CI.

Improved Decision-Making and Resource Management

Most participants pointed out that CI can increase decision-making accuracy and optimise resource distribution and usage. For instance, Participant 1 said, “CI can enable us to do better in decision making and resource utilisation”, and similarly, Participant 5 said, “CI can enable us to make better decisions and utilise resources better, hence increasing our effectiveness”.

Enhanced Collaboration and Partnerships

Some of the respondents appreciated the possibility of CI to spot new partnership opportunities and sources of financing for the sector. Participant 2 said, “Yes, CI can support decisions, reveal new partnership opportunities, and increase our effectiveness”. Participant 3 said, “Yes, CI could be beneficial in searching for new funds and potential partners”.

Increased Adaptability and Responsiveness

They noted that CI can offer an understanding of the dynamic environment in the humanitarian sector as well as the needs of beneficiaries, which enables organisations to adjust their approaches, strategies, programmes, and interventions. Participant 7 said, “By giving information about humanitarian context shift, CI can support decision-making in the context of a shift in strategies and interventions”. At the same time, Participant 4 shared their opinion, “By giving information about the needs of the beneficiaries, CI can help to adjust programs and services”.

Enhanced Organisational Effectiveness and Impact

Some participants pointed out that CI can enhance the degree of productivity and efficiency and increase the effectiveness and impact of the organisational mission. During the interviews, Participant 6 said, “CI can make better decisions, find new partnerships, and increase effectiveness”. Participant 9 said, “CI can assist in better decision-making, increasing effective use of resources.

5. Discussion

5.1. Awareness and Adoption of CI in the Humanitarian Sector in Ghana

The study reveals that awareness of CI among humanitarian organisations in Ghana is moderate, but the actual adoption and application of CI are still very low. While 64.7% of the respondents said they were familiar with CI, only 44.2% stated that they were using CI practices or using CI to support strategic decision-making. In addition, while using an enterprise-scale example, most organisations do not have a formal CI process; 44.1% of respondents were in the disagree category as to whether they had a formal CI process, and 58.8% were in the disagree category as to whether they have dedicated CI staff.

These findings contradict some studies in other settings that have noted a discrepancy between CI knowledge and application. For example, Nenzhelele [49] revealed that although the South African property sector companies understood CI, they did not have well-defined CI procedures. Similarly, Tsokanas and Fragouli [52] found high CI awareness levels but low actual knowledge and formal processes in the Greek pharmaceutical industry.

However, the CI awareness and adoption levels of Ghanaian humanitarian organisations seem to be lower than those of other industries and regions. For instance, Priporas [51] identified active CI monitoring and its use in strategic decisions in small US liquor retail firms. Murege [54] documented that Kenyan mobile phone service providers commonly use CI to improve competitiveness.

Qualitative findings enriched the study by explaining that Ghanaian humanitarian organisations have little insight into CI implementation despite the defined comprehension of CI. One of the participants said, “Our organisation is aware of CI, but it does not know how best to utilise it”. This agrees with the study by Bulley et al. [53], which states that organisations understand the significance of CI but fail to capture its entire value.

The lack of systematic CI practices in many Ghanaian humanitarian organisations, which use information acquired through informal networks, differs from the more systematic methods described in some studies. For example, Viviers and Muller [62] discovered that CI was regarded as an essential business function in most companies in South Africa.

5.2. Barriers to Adopting CI in Ghana’s Humanitarian Sector

The study’s results on the difficulties faced in implementing competitive intelligence (CI) by Ghana’s humanitarian organisations also reveal several issues. Still, the main problem is the lack of resources. The study found that the most significant constraints were financial constraints, poor technology, and the scarcity of qualified personnel. These findings agree with numerous previous works in other settings that show that resource constraints frequently hinder CI uptake in various industries and geographies.

For instance, Wright et al. [58] showed that a lack of financial resources and CI knowledge limited the adoption of CI among Turkish SMEs, a situation similar to that in Ghana. Likewise, Priporas et al. [56] found that the lack of qualified personnel and perceived high costs were major barriers to Greek companies adopting CI, which aligns with the resource challenges the Ghanaian humanitarian organisations encountered.

Nevertheless, the role of technological infrastructure as a barrier may be more apparent in the Ghanaian context than in some developed countries. This follows Teo and Choo’s [81] argument that technological readiness is a critical factor influencing the adoption of CI, specifically in the developing world.

Interestingly, organisational culture and resistance to change were not as much of an issue in Ghana as the lack of resources. This contrasts the study of April and Bessa [55] on a global energy multinational where organisational culture emerged as a critical impediment to CI implementation. The difference could have arisen due to the unique nature of the humanitarian field or the specific conditions in Ghana.

The qualitative data offer a richer picture and suggest factors not captured in the quantitative results, such as a lack of management support and other organisational priorities. According to one of the participants, “some of the greatest obstacles include inadequate funding, competition with other initiatives, and inadequate support from the top management”. This is similar to the findings of Garcia-Alsina et al. [57] in the Spainish university system, whereby other organisational constraints and competing priorities were seen as significant barriers to integrating CI practices.

Specifically, legal and ethical issues emerged as the least critical barrier in the Ghanaian humanitarian sector. This contrasts with some other corporate research, such as that of Crane [82], which focuses on the ethical issues of CI gathering. The difference might be attributed to the humanitarian sector’s unique context and sets of values.

The results also identified a lack of awareness of the benefits of CI as a barrier, though fewer participants mentioned it. This conforms to Priporas et al.’s [56] findings of a general lack of awareness as a significant barrier to CI adoption by Greek firms, pointing to the fact that awareness and enlightenment should not be underestimated in any organisation and context.

5.3. The Benefits and Opportunities of CI in the Humanitarian Sector of Ghana

The findings of this study on competitive intelligence (CI) in the humanitarian sector of Ghana have shown that there are a lot of favourable outcomes and prospects for organisational performance and improvement. Several benefits were found, with the first being CI’s impact on overall organisational effectiveness and outcomes, and the second being the ability of CI to assist organisations in navigating through changing needs and systems.

These findings are consistent with the previous research in other domains. For instance, Olszak et al. [59] revealed that CI increases organisational performance in monitoring environments and the quality of decisions made at all management levels. Similarly, Placer-Maruri et al. [60] established that CI helped SMEs to be more flexible in their approach to addressing the changes in the environment, which is in accord with the Ghanaian humanitarian organisations’ view of CI as a tool for adaptability.

The study also pointed to the potential of CI for enhancing resource management, in concurrence with Agarwal’s [63] observation that CI can transform raw data into useful information for decision-making. This benefit is important, especially for the Ghanaian humanitarian sector, a scarce resource environment.

Specifically, the Ghanaian humanitarian sector’s view of CI as a means of identifying collaboration possibilities is congruent with Viviers and Muller’s [62] conclusion that CI is essential for increasing organisational and national competitiveness. However, this is presented more cooperatively than competently in the humanitarian context, a distinctive characteristic of the sector.

These results are consistent with the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, which asserts that the source of an organisation’s competitive advantage lies in its resources and capabilities [17]. From the point of view of Ghanaian humanitarian organisations, CI can be seen as a factor that may provide a competitive advantage by increasing the effectiveness of decision-making, optimising resource management and improving organisational agility—all of which can be considered valuable, rare, and imitable resources.

The qualitative findings also provide evidence for this congruence with RBV. Thus, participants pointed to the potential of CI to help make better decisions and manage resources, collaborate, be more adaptable, and increase organisational performance. According to one of the participants, “CI can help us to make good decisions and to use resources to the most advantage, thus helping us to be more effective”. This view is consistent with Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven’s [24] argument that RBV-oriented strategies, such as strategic alliances (CI can enable), enhance a company’s resources and competitiveness.

However, it should be pointed out that although the perceived benefits align with the studies conducted in corporate environments, the humanitarian sector’s objectives may result in different usage of these benefits. For instance, Supardi and Setiahati [61] noted that CI is essential to attaining sustainable competitive advantage in education institutions; in the case of Ghanaian humanitarian organisations, CI appears to be used as a tool to enhance service delivery and meet the needs of the beneficiaries.

5.4. The Limitations of the Study

While providing valuable insights into competitive intelligence (CI) adoption in Ghana’s humanitarian sector, this study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. Firstly, the research focused solely on humanitarian organisations in Ghana, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other sectors or countries. The relatively small sample size of 34 organisations, although representing the entire population of humanitarian organisations in Ghana according to the Logistics Capacity Assessment, may not capture the full diversity of perspectives within the sector.

Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data from organisational representatives, which could be subject to social desirability bias or limited by respondents’ knowledge of their organisation’s CI practices. The study’s cross-sectional nature provides only a snapshot of CI adoption at a specific time, potentially missing long-term trends or changes in CI implementation.

Furthermore, while the mixed-methods approach strengthened the findings, the researchers’ interpretations influenced the qualitative data from interviews. Lastly, the study did not measure the impact of CI on organisational performance, relying instead on perceived benefits.

5.5. Suggestions for Further Studies

Subsequent research can further advance the knowledge base of this study by studying the experiences and modus operandi of humanitarian firms that have incorporated and deployed CI. Such detailed case studies will enable the identification of suitable strategies, activities and factors that can enhance CI integration in the humanitarian sector. Further, cross-sectional research based on one region or country can explain the impact of cultural, political, and socio-economic factors on CI in the humanitarian sector.

Moreover, subsequent studies should investigate the potential of big data and analytics, as well as AI and machine learning, to develop CI abilities and meet the specific needs of humanitarian organisations. Another promising research direction is exploring the ethical issues and standards for properly using such technologies in the humanitarian sector.

6. Conclusions

From the analysis of the results of this study, one can conclude that there is adequate information about CI. However, the practical use of CI concepts in humanitarian organisations in Ghana is still unsatisfactory. The study shows poor CI awareness and knowledge level, a lack of organised CI activities, and several challenges that would hamper CI adoption and utilisation in these organisations.

The most eminent barriers include a lack of financial capital, qualified staff, and inadequate technology support. These barriers are associated with organisational culture, a lack of leadership commitment, and competing priorities in adopting CI.

However, the study also identifies several benefits and opportunities that CI presents for Ghana’s humanitarian sector. The benefits highlighted by the participants include better decision-making and resource allocation, improved cooperation and partnerships, increased flexibility and response, and improved organisational efficiency and outcomes.

Recommendations

Based on these findings, several recommendations can be made to promote the effective adoption and implementation of CI in the Ghanaian humanitarian sector:

- Effective training, workshops, and seminars must be conducted to improve the awareness and knowledge of CI among humanitarian organisations based on their needs and type of work;

- Ensure the availability of adequate funds and put in place relevant technological tools to fund CI activities;

- Train and build the capacity of personnel by conducting training and capacity enhancement programmes tailored towards CI competencies;

- Cultivate an organisational climate that embraces CI as an essential aspect and supports the application of CI in the decision-making process;

- Involve management and obtain their approval by arguing for the importance of CI for organisational improvement and outcomes;

- Implement proper CI procedures and employ people to oversee and govern CI procedures in the organisation;

- Promote cross-organisational cooperation and knowledge management to benefit from the wisdom of many in the humanitarian system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A. and O.A.O.; methodology, E.A.; software, E.A.; validation, O.A.O. and L.N.; formal analysis, E.A and L.N.; investigation, E.A. and O.A.O.; resources, L.N and O.A.O.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, L.N. and O.A.O.; supervision, L.N and O.A.O.; project administration, E.A and L.N.; funding acquisition, O.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and institutional policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Durban University of Technology and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire

Demographics:

- 1.

- Name of the organisation: _______________

- 2.

- Type of organisation:

- (a)

- International NGO

- (b)

- Local NGO

- (c)

- Community-based organisation (CBO)

- (d)

- Other (please specify): _______________

- 3.

- Number of years the organisation has been operating in Ghana: _______________

- 4.

- Number of employees in the organisation: _______________

- 5.

- Respondent’s position in the organisation: _______________

Current state of CI adoption

Please indicate your level of agreement with the Current State of Competitive Intelligence adoption in your organisation on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree):

| Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Our organisation is aware of the concept of Competitive Intelligence (CI) | |||||

| Our organisation currently employs CI practices. | |||||

| Our organisation has a dedicated CI unit or personnel. | |||||

| Our organisation has a formal CI process in place. | |||||

| Our organisation uses CI for strategic decision-making. |

Barriers to CI adoption

Please indicate your level of agreement to the Barriers to Competitive Intelligence adoption in your organisation on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree):

| Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Lack of financial resources | |||||

| Lack of skilled personnel | |||||

| Lack of technological infrastructure | |||||

| Organisational culture and resistance to change | |||||

| Legal and ethical concerns |

Benefits and opportunities of CI adoption

Please indicate your level of agreement to the benefits and opportunities of Competitive Intelligence adoption in your organisation on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree):

| Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| CI can enhance our organisation’s decision-making capabilities. | |||||

| CI can improve our organisation’s resource allocation and management. | |||||

| CI can help our organisation identify new opportunities for collaboration and partnerships. | |||||

| CI can contribute to our organisation’s overall effectiveness and impact. | |||||

| CI can help our organisation adapt to the changing needs of beneficiaries and the humanitarian landscape. |

Appendix B

Interview Questions

- How would you describe your organisation’s current level of awareness and understanding of Competitive Intelligence (CI)?

- What CI practices, if any, does your organisation currently employ? Can you provide some examples?

- What are the main challenges or barriers your organisation faces in adopting or implementing CI practices?

- How do factors such as financial resources, skilled personnel, technological infrastructure, organisational culture, and legal/ethical concerns impact your organisation’s ability to adopt CI?

- In what ways do you believe CI can benefit your organisation, particularly in terms of decision-making, resource management, collaboration, and overall effectiveness?

- Can you share any specific examples or instances where CI has been or could be particularly useful for your organisation?

- How do you think CI can help your organisation adapt to the changing needs of beneficiaries and the evolving humanitarian landscape in Ghana?

- What steps do you think your organisation needs to take to overcome the barriers to CI adoption and harness its potential benefits?

- How can CI contribute to knowledge sharing and retention within your organisation, and how can this lead to a sustainable competitive advantage?

- In your opinion, what role can CI play in enhancing your organisation’s ability to respond effectively to humanitarian crises in Ghana?

References

- Arhin, A.A.; Kumi, E.; Adam, M.A.S. Facing the bullet? Non-Governmental Organisations’ (NGOs’) responses to the changing aid landscape in Ghana. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Non-Profit Organ. 2018, 29, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biadoo, J. Challenges and Strategies for Rapid Response in Disaster Relief Operations in Ghana. Texila Int. J. Manag. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.P.; Richards, A.K.; Marx, M.A.; Checchi, F.; Kozuki, N. Assessing community health worker service delivery in humanitarian settings. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 010307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrecht, A.; Warner, A.T. More than Just Luck: Innovation in Humanitarian Action; Humanitarian Innovation Fund: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- El Fadili, S.; Gmira, F. Competitive Intelligence: Leaven of a New Managerial Device for Decision Support. TELKOMNIKA Indones. J. Electr. Eng. 2015, 16, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, A. Competitive intelligence process integrative model based on a scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 13, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.E. The evolution of competitive intelligence. Int. Rev. Strateg. Manag. 1995, 6, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kabue, L.W.; Kilika, J.M. Firm resources, core competencies and sustainable competitive advantage: An integrative theoretical framework. J. Manag. Strategy 2016, 7, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarao, I.; Wynia, M.K.; Burkle, F.M., Jr. The elephant in the room: Collaboration and competition among relief organisations during high-profile disasters. J. Clin. Ethics 2010, 21, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwitter, A. Humanitarian Intelligence: A Practitioner’s Guide to Crisis Analysis and Project Design; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Menninga, E.J. Competition, Aid, and Violence against Civilians. Int. Interact. 2020, 46, 696–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, A.; Lycett, M. Big data and humanitarian supply networks: Can Big Data give voice to the voiceless? In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), San Jose, CA, USA, 20–23 October 2013; pp. 432–437. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.; Schmitt, A. Strategy and knowledge management in humanitarian organisations. In Decision-Making in Humanitarian Operations: Strategy, Behaviour and Dynamics; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Adzoa, T.V. Effective training and development as a strategic tool for competitiveness: A Ghanaian private university experience. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 7, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vannini, S.; Gomez, R.; Newell, B.C. Mind the five: Guidelines for data privacy and security in humanitarian work with undocumented migrants and other vulnerable populations. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 71, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoetker, G. Taking the competitive intelligence effort overseas: Four special challenges. Compet. Intell. Rev. 1996, 7, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M. The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J. Strategic assets and organisational rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. In Knowledge and strategy; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Schoonhoven, C.B. Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L.; Butler, J.E. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaner, L. Competitive Intelligence: How to Gather Analyse and Use Information to Move Your Business to the Top; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pellissier, R.; Nenzhelele, T.E. Towards a universal competitive intelligence process model. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calof, J.L.; Wright, S. Competitive intelligence: A practitioner, academic and inter-disciplinary perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A.S. Competitive intelligence research: An investigation of trends in the literature. J. Intell. Stud. Bus. 2015, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, J.P. Key intelligence topics: A process to identify and define intelligence needs. Compet. Intell. Rev. 1999, 10, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, C.S.; Bensoussan, B.E. Business and Competitive Analysis: Effective Application of New and Classic Methods; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, R. Competitive intelligence process and tools for intelligence analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2008, 108, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, P.L.; Calof, J.L. Competitive intelligence: A multiphasic precedent to marketing strategy. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 766–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tej Adidam, P.; Banerjee, M.; Shukla, P. Competitive intelligence and firm’s performance in emerging markets: An exploratory study in India. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, P.; Van Doren, D.C. Competitive intelligence in service marketing: A new approach with practical application. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maune, A. Competitive intelligence as an enabler for firm competitiveness: An overview. J. Gov. Regul. 2014, 3, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanev, S.; Bailetti, T. Competitive intelligence information and innovation in small Canadian firms. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Helfat, C.E. Strategic renewal of organisations. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.E.; Le Bon, J.; Rapp, A. Gaining and leveraging customer-based competitive intelligence: The pivotal role of social capital and salesperson adaptive selling skills. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryo-Dabrah, A.; Ansong, R.S.; Setorglo, J.; Steiner-Asiedu, M. Food and nutrition security situation in Ghana: Nutrition implications for national development. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2021, 21, 18005–18018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R. Ghana: Defining the African challenge. Lancet 2001, 358, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobih, N. In Search of an Alternative Model of Development in Africa: The Role of the State, Donor Agencies, International Non-Governmental Organisations and Commmunity-Based Organisations in Ghana’s Development. Master’s Thesis, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, G.; O’Dwyer, B.; Unerman, J. NGO accountability: Retrospective and prospective academic contributions. Acc. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, S.S. Developing Managers and Leaders: Experiences and Lessons from International NGOs; Hauser Center-Harvard Humanitarian Initiative Special Report; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/7784444 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Issifu Mr, A.K. Role of civil society organisations in conflict resolution and peacebuilding in Ghana. J. Interdiscip. Confl. Sci. 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, E.; Antwi, J.; Kendie, S.B. Disaster Risk Management: The Exercise of Power, Legitimacy and Urgency in Stakeholder Role in Ghana. Int. J. Environtment Clim. Change 2021, 11, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, B.; Frondizi, R.; Rossi, N. Governing aid coordination in regional platforms: The G20 Compact with Africa case. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023, 89, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenzhelele, T.E. Competitive intelligence practice in the South African property sector. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, W. Competitive intelligence in Tunisian companies. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2011, 24, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.V. Competitive intelligence practice in liquor retailing: Evidence from a longitudinal case analysis. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokanas, N.; Fragouli, E. Competitive intelligence for the pharmaceutical industry: The case of Greece. Sci. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bulley, C.A.; Baku, K.F.; Allan, M.M. Competitive intelligence information: A key business success factor. J. Mgmt. Sustain. 2014, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murege, F.W. Competitive Intelligence as a Strategic Tool by the Mobile Phone Operators in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- April, K.; Bessa, J. A critique of the strategic competitive intelligence process within a global energy multinational. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2006, 4, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas, C.V.; Gatsoris, L.; Zacharis, V. Competitive intelligence activity: Evidence from Greece. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]