Supernatants from Water Extraction—Ethanol Precipitation of Fagopyrum tararicum Seeds Enhance T2DM Management in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SWEPFT Preparation

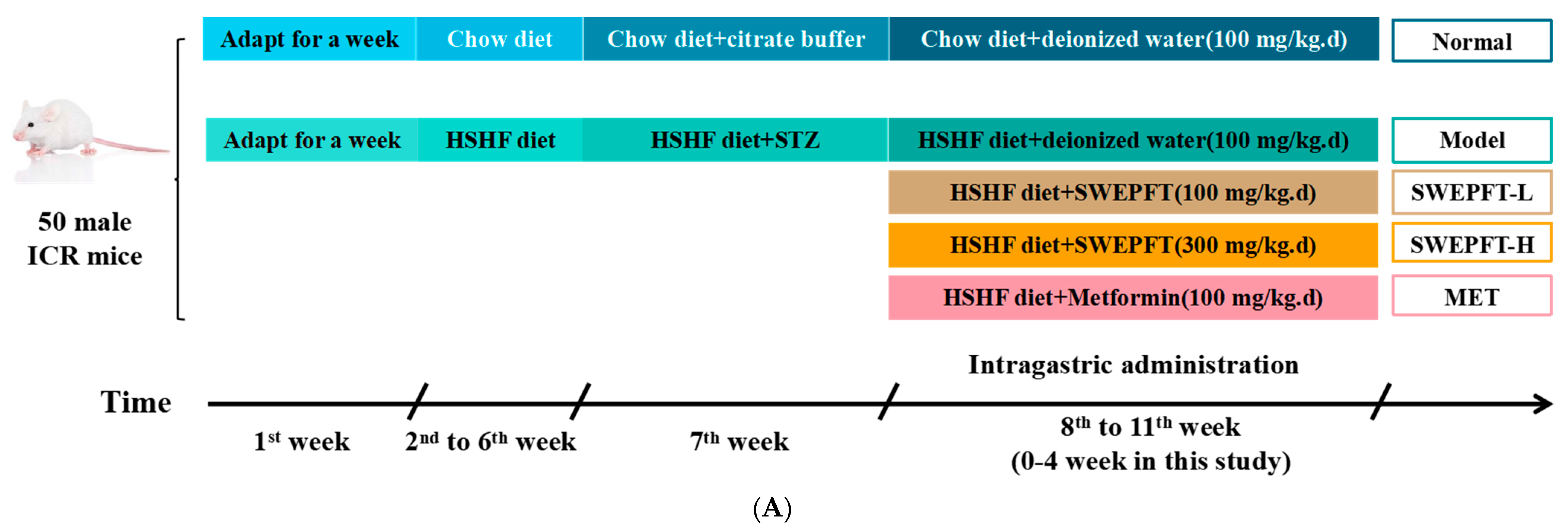

2.2. Animal Experiment

2.3. Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA) Insulin Correlation Indexes

2.4. Examination of Serum and Liver Biochemical Indexes

2.5. qPCR

2.6. Examination of Cecal Microbiota

2.7. Assessment of SCFAs in Cecum

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Composition of SWEPFT

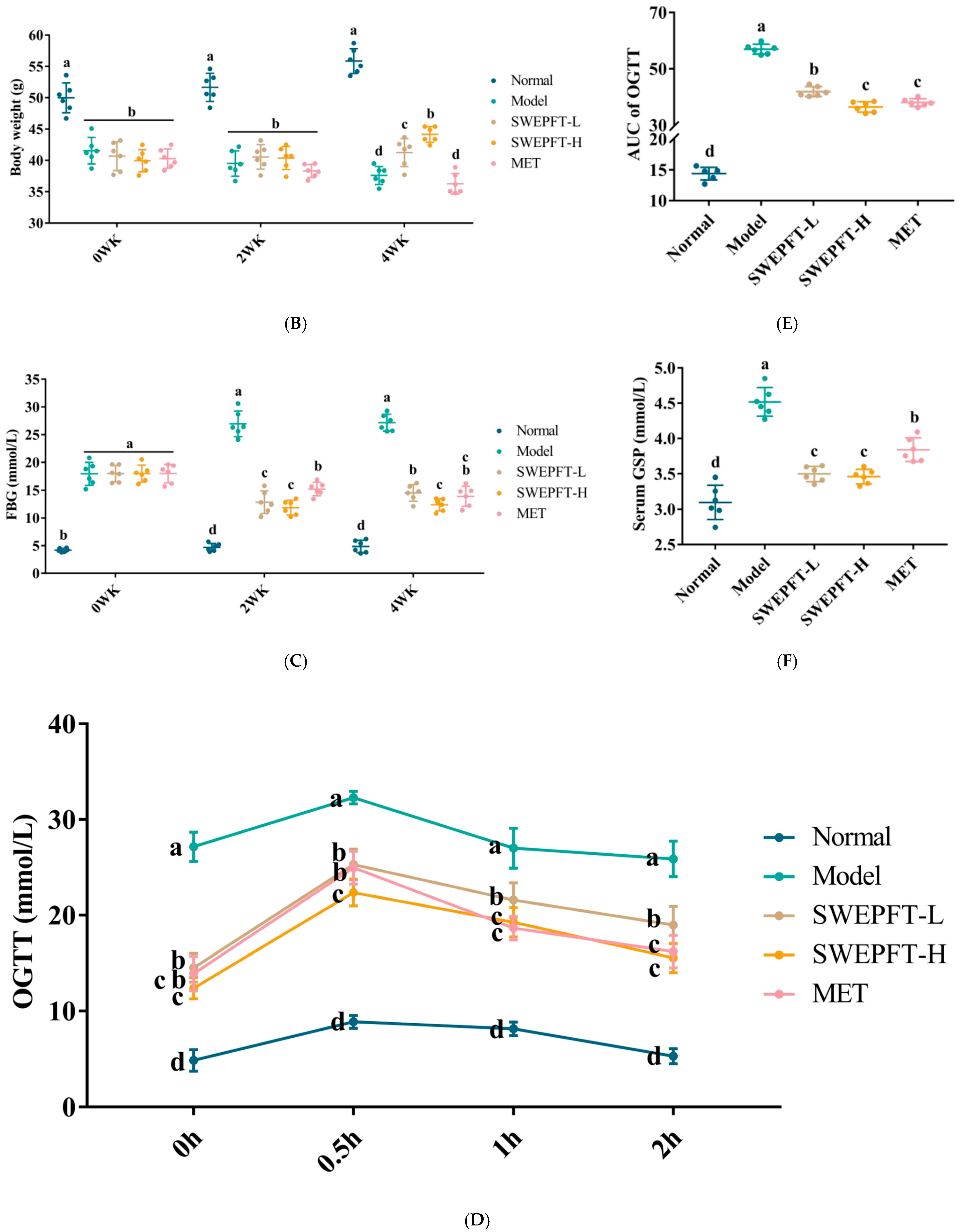

3.2. Effects of SWEPFT on BW, FBG, and AUC of OGTT and Serum GSP Levels in Mice

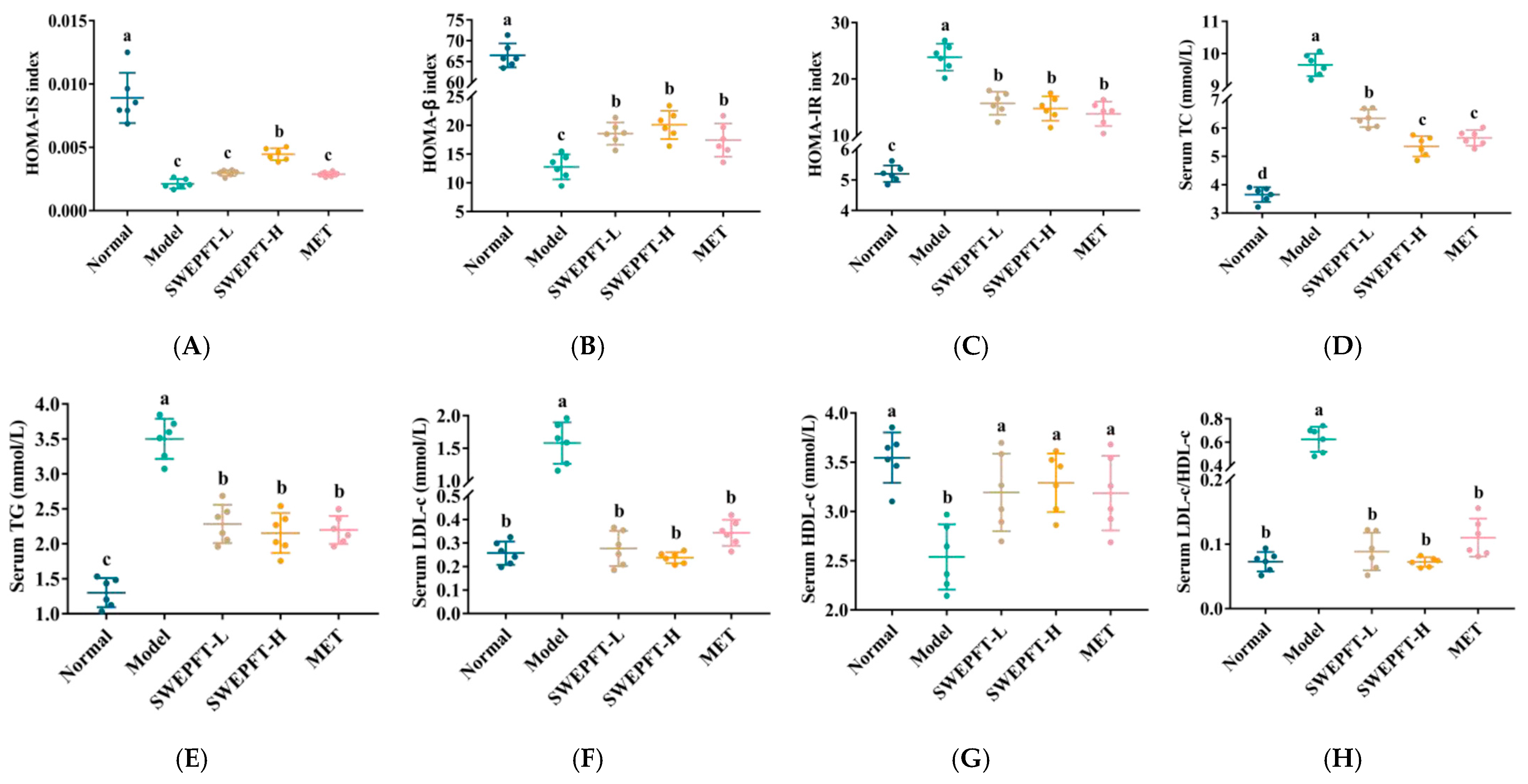

3.3. Effects of SWEPFT on Insulin Correlation Indexes and Serum Biochemical Indicators

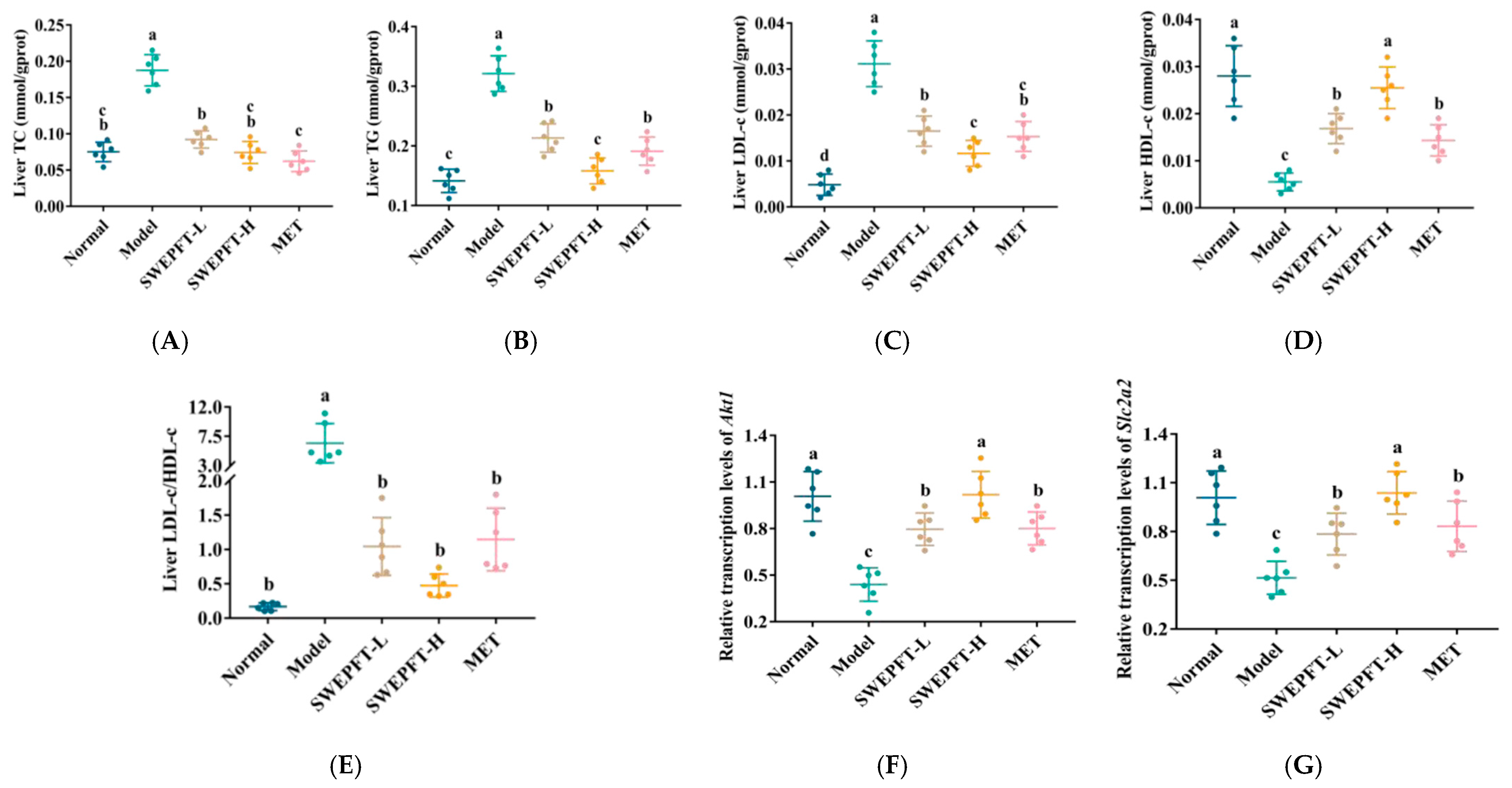

3.4. Effects of SWEPFT on Biochemical Indicators and Key Genes in the Liver

3.5. Effects of SWEPFT on Intestinal Microbial Communities and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Cecum Contents

3.6. Effects of Link Between Differential Bacterial Genera and Parameters of Hypoglycemia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, T.; Chen, X.X.; Wang, J.C.; Zhang, B.; Sun, Y.L.; Xin, J.; Shao, F.L.; Li, X.P. Laminaria japonica polysaccharide protects against liver and kidney injury in diabetes mellitus through the AhR/CD36 pathway. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphumulo, S.C.; Pretorius, E. Role of circulating microparticles in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Implications for pathological clotting. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 48, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Barrea, L.; Caprio, M.; Ceriani, F.; Chavez, A.O.; Ghoch, M.E.; Frias-Toral, E.; Mehta, R.J.; Mendez, V.; Paschou, S.A.; et al. Nutritional guidelines for the management of insulin resistance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 6947–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungau, S.G.; Vesa, C.M.; Bustea, C.; Purza, A.L.; Tit, D.M.; Brisc, M.C.; Radu, A.F. Antioxidant and hypoglycemic potential of essential oils in diabetes mellitus and its complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Jiao, L.L.; Wang, Y. Fecal fatty acid profile reveals the therapeutic effect of red ginseng acidic polysaccharide on type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.Q.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, W.; Feng, K.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.L.; Li, P. Tangshen Formula alleviates inflammatory injury against aged diabetic kidney disease through modulating gut microbiota composition and related amino acid metabolism. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 188, 112393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliada, A.; Syzenko, G.; Moseiko, V.; Budovska, L. Association between body mass index and firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in an adult ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Miyamoto, S.; Darshi, M.; Torralba, M.G.; Kwon, K.; Sharma, K.; Pieper, R. Gut microbial changes in diabetic db/db mice and recovery of microbial diversity upon pirfenidone treatment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryabor, G.; Atashzar, M.R.; Kabelitz, D.; Meri, S.; Kalantar, K. The effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus on organ metabolism and the immune system. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Marcos, J.A.; Perez-Jimenez, F.; Camargo, A. The role of diet and intestinal microbiota in the development of metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 70, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibony, R.W.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Drug therapies for diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Gao, W.G.; Wan, H.L.; Xu, F.M.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, X.; Ji, Q.H. Efficacy and safety of alogliptin versus acarbose in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients with high cardiovascular risk or coronary heart disease treated with aspirin and inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy or drug-naive: A multicentre, randomized, open-label, prospective study (ACADEMIC). Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.H.; Hua, X.Y.; Yu, A.H.M.; Peh, E.W.Y.; See, E.E.; Henry, C.J. A review on buckwheat and its hypoglycemic bioactive components in food systems. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 12, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Sun, S.S.; Li, M.Y.; Gao, B.; Zhang, L.T. Structural characterization and tartary buckwheat polysaccharides alleviate insulin resistance by suppressing SOCS3-induced IRS1 protein degradation. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 89, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.R.; Ren, R.R.; Yao, L.L.; Tong, L.; Li, J.L.; Wang, D.H.; Gu, S.B. Preparation, characterization, antioxidant, and hypoglycemic activity of polysaccharide nano-selenium from Fagopyrum tataricum. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 7967–7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.Q.; He, R.L.; Zhao, J.L.; Xiang, D.B.; Zou, L.; Peng, L.X.; Zhao, G. In-depth mapping of the seed phosphoproteome and N-glycoproteome of Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) using off-line high pH RPLC fractionation and nLC-MS/MS. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Zhang, N.N.; Guo, S.; Liu, S.J.; Hou, Y.F.; Li, S.M.; Ho, C.T.; Bai, N.S. Glycosides and flavonoids from the extract of Pueraria thomsonii Benth leaf alleviate type 2 diabetes in high-fat diet plus streptozotocin-induced mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3931–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Gao, Y.B.; Duan, L.J.; Wei, S.H.; Liu, J.; Tian, L.M.; Quan, J.X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.X.; Yang, J.K. Metformin ameliorates skeletal muscle insulin resistance by inhibiting miR-21 expression in a high-fat dietary rat model. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 98029–98039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Minacapelli, C.D.; Tait, C.; Gupta, K.; Bhurwal, A.; Catalano, C.; Dafalla, R.; Metaxas, D.; Rustgi, V.K. Training of computational algorithms to predict NAFLD activity score and fibrosis stage from liver histopathology slides. Comput. Meth. Prog. Bio. 2021, 207, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.D.; He, X.Y.; Lin, Z.S.; Zhu, Y.X.; Jiang, X.Q.; Zhao, L.Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, L.G.; Xu, W.; Chen, Z.G.; et al. 6,8-(1,3-Diaminoguanidine) luteolin and its Cr complex show hypoglycemic activities and alter intestinal microbiota composition in type 2 diabetes mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3572–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.R.; Zhao, L.Y.; Zhu, F.R.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.Y.; Chen, Z.C.; Lv, X.C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B. Anti-diabetic effects of ethanol extract from Sanghuangporous vaninii in high-fat/sucrose diet and streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by modulating gut microbiota. Foods 2022, 11, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Liu, T.T.; Ma, F.; Fu, T.F.; Yang, L.P.; Mao, H.M.; Wang, Y.Y.; Peng, L.; Li, P.; Zhan, Y.L. Roles of Sirt1 and its modulators in diabetic microangiopathy: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; She, F.; Yi, R.K.; Hu, T.T.; Liu, W.W.; Zhao, X. Mengding yellow bud polyphenols protect against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in mice via inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.X.; Xiao, Y.X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, Y.B. Study on the correlation between metabolism, insulin sensitivity and progressive weight loss change in type-2 diabetes. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.D.; He, X.Y.; Liu, J.W.; Zeng, F.; Chen, L.G.; Xu, W.; Shao, R.; Huang, Y.; Farag, M.A.; Capanoglu, E.; et al. Amelioration of type 2 diabetes by the novel 6, 8-guanidyl luteolin quinonechromium coordination via biochemical mechanisms and gut microbiota interaction. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 46, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.K.; Wang, X.Q.; Jiang, X.; Kong, F.S.; Wang, S.M.; Yan, C.Y. Antidiabetic effects of Morus alba fruit polysaccharides on high-fat diet- and streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Miao, Q.Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, M.M. Effects of chitosan guanidine on blood glucose regulation and gut microbiota in T2DM. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Xing, R.E.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, S.; Yu, H.H.; Li, P.C. Therapeutic potential of enzymatically extracted eumelanin from squid ink in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) ICR mice: Multifaceted intervention against hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, and depression. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.R.; Yang, J.J.; Tan, A.J.; Chen, H.W. Irisin suppresses pancreatic β cell pyroptosis in T2DM by inhibiting the NLRP3-GSDMD pathway and activating the Nrf2-TrX/TXNIP signaling axis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, H.; Kumar, P.; Purohit, A.; Kashyap, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, G.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Hashem, A.; Abd-Allah, E.F.; et al. Improvements in HOMA indices and pancreatic endocrinal tissues in type 2-diabetic rats by DPP-4 inhibition and antioxidant potential of an ethanol fruit extract of Withania coagulans. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Zhu, C.C.; Gao, S.K.; Shao, X.; Chen, X.F.; Zhang, H.; Tang, D.Q. Morus alba leaves ethanol extract protects pancreatic islet cells against dysfunction and death by inducing autophagy in type 2 diabetes. Phytomedicine 2021, 83, 153478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhong, L.; Hu, C.; Zhong, M.C.; Peng, N.; Sheng, G.T. LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio is associated with new-onset NAFLD in Chinese non-obese people with normal lipids: A 5-year longitudinal cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Xiao, J.; Chi, S.X. Piperlongumine attenuates oxidative stress, inflammatory, and apoptosis through modulating the GLUT-2/4 and AKT signaling pathway in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.H.; Xu, J.; Gao, Q.Q.; Wang, Z.F.; Hou, M.X.; Liu, Y.E. Study on the effect of licochalcone A on intestinal flora in type 2 diabetes mellitus mice based on 16S rRNA technology. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8903–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.J.; Lyu, Q.J.; Yang, T.Y.; Cui, S.Y.; Niu, K.L.; Gu, R.H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Xing, W.G.; Li, L.L. Association of intestinal microbiota markers and dietary pattern in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: The Henan rural cohort study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1046333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, Y.C.; Farag, M.A.; Gong, J.P.; Su, Q.L.; Cao, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, H. Dietary flavonoids and gut microbiota interaction: A focus on animal and human studies to maximize their health benefits. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1794–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.Y.; Luo, J.Y.; Bao, Y.H. Effects of Polygonatum sibiricum saponin on hyperglycemia, gut microbiota composition and metabolic profiles in type 2 diabetes mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.Y.; Liu, C.L.; Zhaxi, P.; Kou, X.H.; Liu, Y.Z.; Xue, Z.H. Research progress on hypoglycemic effects and molecular mechanisms of flavonoids: A review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.S.; Zou, J.X.; Wu, M.T.; Deng, Y.D.; Shi, J.W.; Hao, Y.T.; Deng, H.; Liao, W.Z. Hypoglycemic effect of nobiletin via gut microbiota-metabolism axis on hyperglycemic mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2200289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naudhani, M.; Thakur, K.; Ni, Z.J.; Zhang, J.G.; Wei, Z.J. Formononetin reshapes the gut microbiota, prevents progression of obesity and improves host metabolism. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 12303–12324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, A.M.; Dellacassa, E.; Curbelo, R.; Nardin, T.; Larcher, R.; Medrano-Fernandez, A.; del Castillo, M.D. Health-promoting potential of mandarin pomace extracts enriched with phenolic compounds. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.W.; Liu, C.; Chen, M.J.; Zou, J.F.; Zhang, Z.M.; Cui, X.; Jiang, S.; Shang, E.X.; Qian, D.W.; Duan, J.A. Scutellariae radix and coptidis rhizoma ameliorate glycolipid metabolism of type 2 diabetic rats by modulating gut microbiota and its metabolites. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, L.J.; Zhou, G.S.; Li, X.B. Regulating the gut microbiota and SCFAs in the faeces of T2DM rats should be one of antidiabetic mechanisms of mogrosides in the fruits of Siraitia grosvenorii. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 274, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.L.; Xu, Y.B.; Zhang, H.; Muema, F.W.; Guo, M.Q. Gymnema sylvestre extract ameliorated streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia in T2DM rats via gut microbiota. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørgaard, A.; Jepsen, S.L.; Holst, J.J. Short-chain fatty acids and regulation of pancreatic endocrine secretion in mice. Islets 2019, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, P.; Mosquera, A.; Muntané, J.; Ferrandiz, F.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L.; de Pablo, F.; González-Canudas, J.; Valverde, A.M. Differential effects of metformin glycinate and hydrochloride in glucose production, AMPK phosphorylation and insulin sensitivity in hepatocytes from non-diabetic and diabetic mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 123, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreight, L.J.; Bailey, C.J.; Pearson, E.R. Metformin and the gastrointestinal tract. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Drzewoski, J.; Kozłowska, M.; Krekora, J.; Śliwińska, A. The gut microbiota-related antihyperglycemic effect of metformin. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukaev, E.; Kirillova, E.; Tokareva, A.; Rimskaya, E.; Starodubtseva, N.; Chernukha, G.; Priputnevich, T.; Frankevich, V.; Sukhikh, G. Impact of gut microbiota and SCFAs in the pathogenesis of PCOS and the effect of metformin therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Kumar, S.; Lee, J.H.; Chang, D.H.; Kim, D.S.; Choi, S.H.; Rhee, M.S.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, M.H.; Kim, B.C. Genome sequence of Oscillibacter ruminantium strain GH1, isolatedfrom rumen of Korean native cattle. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Lytras, T.; Bonovas, S. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, G.S. Empagliflozin ameliorates type 2 diabetes mellitus-related diabetic nephropathy via altering the gut microbiota. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.X.; Chen, H.R.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y.; Chan, E.C.Y. Lactobacillus paracasei IMC 502 ameliorates type 2 diabetes by mediating gut microbiota-SCFA-hormone/inflammation pathway in mice. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2023, 103, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Sun, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, T.; Ye, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, H.; Ye, Z.; et al. Calorie restriction ameliorates hyperglycemia, modulates the disordered gut microbiota, and mitigates metabolic endotoxemia and inflammation in type 2 diabetic rats. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassatoui, M.; Saffarian, A.; Mulet, C.; Jamoussi, H.; Gamoudi, A.; Halima, Y.B.; Hechmi, M.; Abdelhak, S.; Abid, A.; Sansonetti, P.J.; et al. Gut microbiota profile and the influence of nutritional status on bacterial distribution in diabetic and healthy Tunisian subjects. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20220803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.L.; Wang, R.; Santos, J.M.; Elmassry, M.M.; Stephens, E.; Kim, N.; Neugebauer, V. Ginger alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity and anxio-depressive behavior in rats with diabetic neuropathy through beneficial actions on gut microbiome composition, mitochondria, and neuroimmune cells of colon and spinal cord. Nutr. Res. 2024, 124, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.Q.; Zhan, M.M.; Yang, X.S.; Xie, P.C.; Xiao, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Song, M.Y. Fermented dietary fiber from soy sauce residue exerts antidiabetic effects through regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and gut microbiota-SCFAs-GPRs axis in type 2 diabetic mellitus mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.F.; Tang, C.; Hu, G.J.; Gao, Z.Z. Targeting gut microbiota as a therapeutic target in T2DM: A review of multi-target interactions of probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, and synbiotics with the intestinal barrier. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 210, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.R.; Chen, K.W.; Li, T.T.; He, X.Y.; Ge, X.D.; Liu, X.Y.; Liu, B.; Zeng, F. Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic activities of Sanghuangporus vaninii compounds in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice via modulation of intestinal microbiota. eFood 2024, 5, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PRIMER NAME | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Actb | TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT | AGCTCATAACAGTCCGCCTAGA |

| Akt1 | ACTCATTCCAGACCCACGAC | CCGGTACACCACGTTCTTCT |

| Slc2a2 | TACGGCAATGGCTTTATC | CCTCCTGCAACTTCTCAAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ge, X.; Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Chen, L.; Shao, R.; et al. Supernatants from Water Extraction—Ethanol Precipitation of Fagopyrum tararicum Seeds Enhance T2DM Management in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Communities. Foods 2026, 15, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010143

Ge X, Du X, Wang Y, Yang Y, Gao X, Zhou Y, Jiang Y, Xiao S, Chen L, Shao R, et al. Supernatants from Water Extraction—Ethanol Precipitation of Fagopyrum tararicum Seeds Enhance T2DM Management in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Communities. Foods. 2026; 15(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Xiaodong, Xiaoxuan Du, Yaolin Wang, Yang Yang, Xiaoyu Gao, Yuchang Zhou, Yuting Jiang, Shiqi Xiao, Ligen Chen, Rong Shao, and et al. 2026. "Supernatants from Water Extraction—Ethanol Precipitation of Fagopyrum tararicum Seeds Enhance T2DM Management in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Communities" Foods 15, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010143

APA StyleGe, X., Du, X., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., Gao, X., Zhou, Y., Jiang, Y., Xiao, S., Chen, L., Shao, R., Xu, W., Kim, K.-M., & Wu, N. (2026). Supernatants from Water Extraction—Ethanol Precipitation of Fagopyrum tararicum Seeds Enhance T2DM Management in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Communities. Foods, 15(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010143