Assessing the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Answering Dental Caries Multiple-Choice Questions: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Google Gemini Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

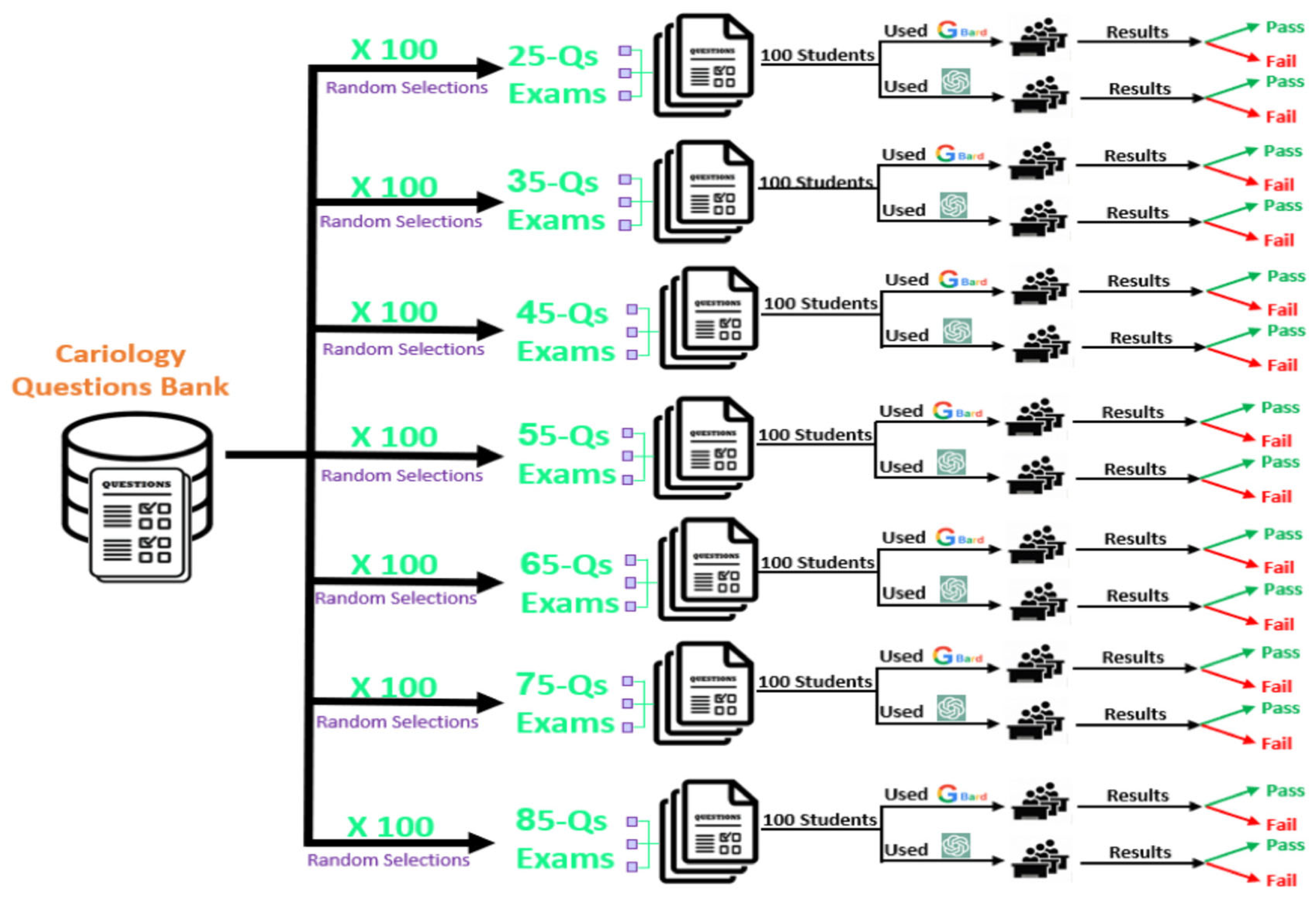

2. Materials & Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apell, P.; Eriksson, H. Artificial intelligence (AI) healthcare technology innovations: The current state and challenges from a life science industry perspective. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2023, 35, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.M.; Azhari, A.A.; Fawaz, K.A.; Ahmed, H.M.; Alsadah, Z.M.; Majumdar, A.; Carvalho, R.M. Artificial intelligence in the detection and classification of dental caries. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 133, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalifa, K.S.; Ahmed, W.M.; Azhari, A.A.; Qaw, M.; Alsheikh, R.; Alqudaihi, F.; Alfaraj, A. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Caries Detection: A Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A.A.; Helal, N.; Sabri, L.M.; Abduljawad, A. Artificial intelligence (AI) in restorative dentistry: Performance of AI models designed for detection of interproximal carious lesions on primary and permanent dentition. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231216681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.; Macey, R.; Riley, P.; Glenny, A.-M.; Schwendicke, F.; Worthington, H.V.; Clarkson, J.E.; Ricketts, D.; Su, T.-L.; Sengupta, A. Imaging modalities to inform the detection and diagnosis of early caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD014545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, S.N.; Choi, S.H. Detection and diagnosis of dental caries using a deep learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm. J. Dent. 2018, 77, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, D.; Chakrabarti, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Grewal, D.S.; Manrai, K. Artificial intelligence and the radiologist: The future in the Armed Forces Medical Services. BMJ Mil. Health 2020, 166, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.C.S.; Shan, H.; Dahoun, T.; Vogel, H.; Yuan, S. Advancing Drug Discovery via Artificial Intelligence. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cock, C.; Milne-Ives, M.; van Velthoven, M.H.; Alturkistani, A.; Lam, C.; Meinert, E. Effectiveness of Conversational Agents (Virtual Assistants) in Health Care: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e16934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukenze, B.; Mousannif, H.; Haqiq, A. Predictive Analytics in Healthcare System Using Data Mining Techniques. The Fourth International Conference on Database and Data Mining. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseni, A.; Moustafa, N.; Janicke, H.; Liu, P.; Tari, Z.; Vasilakos, A.V. Security and Privacy for Artificial Intelligence: Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, D.; Matthews, J.; Talagala, N. Managing Bias in AI. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of The 2019 World Wide Web Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, A. Should Robots Replace Teachers? Mobilisation of AI and Learning Analytics in Education. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication, and Control (ICAC3), Mumbai, India, 3–4 December 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, K. China has started a grand experiment in AI education. It could reshape how the world learns. MIT Technol. Rev. 2019, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Chassignol, M.; Khoroshavin, A.; Klimova, A.; Bilyatdinova, A. Artificial Intelligence trends in education: A narrative overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 1, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, F.; Subosa, M.; Rivas, A.; Valverde, P. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Development; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.M.; Azhari, A.A.; Alfaraj, A.; Alhamadani, A.; Zhang, M.; Lu, C.T. The Quality of AI-Generated Dental Caries Multiple Choice Questions: A Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT and Google Bard Language Models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, S. ChatGPT for Higher Education and Professional Development: A Guide to Conversational AI; University of Rhode Island Libraries: Kingston, RI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kastrati, Z.; Dalipi, F.; Imran, A.S.; Pireva Nuci, K.; Wani, M.A. Sentiment Analysis of Students’ Feedback with NLP and Deep Learning: A Systematic Mapping Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Lancrin, S.a.R.v.d.V. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education: Promises and Challenges; OECD Education Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Eggmann, F.; Weiger, R.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Blatz, M.B. Implications of large language models such as ChatGPT for dental medicine. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Barth, P.; Bean, R. How big data is different. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Deoras, A.; Povey, D.; Burget, L.; Černocký, J. Strategies for training large scale neural network language models. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition & Understanding; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Silberg, J.; Manyika, J. Notes from the AI Frontier: Tackling Bias in AI (and in Humans); McKinsey Global Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasib, K.M.; Rahman, F.; Hasnat, R.; Alam, M.G.R. A Machine Learning and Explainable AI Approach for Predicting Secondary School Student Performance. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 0399–0405. [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht, P.; Declerck, T.; Schlippe, T.; Mandl, T.; Schiffner, D. NLP for student and teacher: Concept for an AI based information literacy tutoring system. In Proceedings of the CIKM (Workshops), Galway, Ireland, 19–20 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.F.; Rahmat, M.K.; Mubarik, M.S.; Alam, M.M.; Hyder, S.I. Artificial Intelligence and Its Role in Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Tay, F.; Gu, L. Application of artificial intelligence in dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.; Adanero, A.; Diaz-Flores Garcia, V.; Freire, Y.; Algar, J. Using a Virtual Patient via an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot to Develop Dental Students’ Diagnostic Skills. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepano, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Zheng, O.; Wang, D.; Yin, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, S.; Yin, H.; Xu, C.; Yang, R.; Zheng, Q.; et al. ChatGPT for Shaping the Future of Dentistry: The Potential of Multi-Modal Large Language Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. ChatGPT and the Future of Medical Writing. Radiology 2023, 307, e223312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeeg, A.; Shazhaev, I.; Mihaylov, D.; Tularov, A.; Shazhaev, I. Voice Assistant Integrated with Chat GPT. Indones. J. 2023, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwitz, R.H.; Ismail, A.I.; Pitts, N.B. Dental caries. Lancet 2007, 369, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrakdar, I.S.; Orhan, K.; Akarsu, S.; Celik, O.; Atasoy, S.; Pekince, A.; Yasa, Y.; Bilgir, E.; Saglam, H.; Aslan, A.F.; et al. Deep-learning approach for caries detection and segmentation on dental bitewing radiographs. Oral Radiol. 2022, 38, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, A.G.; Gehrung, S.; Krois, J.; Chaurasia, A.; Rossi, J.G.; Gaudin, R.; Elhennawy, K.; Schwendicke, F. Detecting caries lesions of different radiographic extension on bitewings using deep learning. J. Dent. 2020, 100, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, F.; Newton, T.; Daher, R.; Abdelaziz, M.; Lodi-Rizzini, A.; Schurmann, F.; Krejci, I.; Markram, H. Caries Detection with Near-Infrared Transillumination Using Deep Learning. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devito, K.L.; de Souza Barbosa, F.; Felippe Filho, W.N. An artificial multilayer perceptron neural network for diagnosis of proximal dental caries. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008, 106, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, J. Detection and diagnosis of the early caries lesion. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsch, V.K. Dental caries: An updated medical model of risk assessment. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 111, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Elhennawy, K.; Paris, S.; Friebertshauser, P.; Krois, J. Deep learning for caries lesion detection in near-infrared light transillumination images: A pilot study. J. Dent. 2020, 92, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udod, O.A.; Voronina, H.S.; Ivchenkova, O.Y. Application of neural network technologies in the dental caries forecast. Wiadomości Lek. 2020, 73, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, S.; Goodini, M.; Ehsani, S.; Mohseni, H.; Azimi, F.; Bakhshandeh, H. Designing of a Computer Software for Detection of Approximal Caries in Posterior Teeth. Iran. J. Radiol. 2015, 12, e16242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; AlSaad, R.; Alhuwail, D.; Ahmed, A.; Healy, P.M.; Latifi, S.; Aziz, S.; Damseh, R.; Alabed Alrazak, S.; Sheikh, J. Large Language Models in Medical Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e48291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaidry, H.M.; Fatani, B.; Alrayes, J.O.; Almana, A.M.; Alfhaed, N.K. ChatGPT in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e38317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puleio, F.; Lo Giudice, G.; Bellocchio, A.M.; Boschetti, C.E.; Lo Giudice, R. Clinical, Research, and Educational Applications of ChatGPT in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, B. Privacy and artificial intelligence: Challenges for protecting health information in a new era. BMC Med. Ethics. 2021, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Islam, S.; Papastergiou, S.; Tzagkarakis, C.; Ciampi, M. A Machine Learning Approach for the NLP-Based Analysis of Cyber Threats and Vulnerabilities of the Healthcare Ecosystem. Sensors 2023, 23, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, A. AI and education: The importance of teacher and student relations. AI Soc. 2019, 34, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Hawn, A. Algorithmic Bias in Education. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 1052–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.A.; MacKnight, R.; Gomes, G. Emergent autonomous scientific research capabilities of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.05332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, M.; Houde, S.; Martino, J.; Mojsilovic, A.; Piorkowski, D.; Richards, J.; Varshney, K.R. Experiences with improving the transparency of AI models and services. In Proceedings of the InExtended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kortz, M.; Budish, R.; Bavitz, C.; Gershman, S.; O’Brien, D.; Scott, K.; Schieber, S.; Waldo, J.; Weinberger, D.; et al. Accountability of AI under the law: The role of explanation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.01134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, C.M.; Carman, M.; Rosman, B.; Georgiadou, Y.; Soden, R. Fairness and accountability of AI in disaster risk management: Opportunities and challenges. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 2, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Examination Length | N per LLM | ChatGPT Mean (%) ± SD | Gemini Mean (%) ± SD | Difference (%) | t-Test (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 questions | 100 | 53.2 ± 6.4 | 61.6 ± 5.8 | +8.4 | <0.001 |

| 35 questions | 100 | 52.4 ± 5.9 | 61.3 ± 5.4 | +8.9 | <0.001 |

| 45 questions | 100 | 52.1 ± 6.1 | 60.9 ± 5.2 | +8.8 | <0.001 |

| 55 questions | 100 | 51.7 ± 5.8 | 60.7 ± 5.1 | +9.0 | <0.001 |

| 65 questions | 100 | 51.5 ± 5.5 | 60.6 ± 4.9 | +9.1 | <0.001 |

| 75 questions | 100 | 51.2 ± 5.6 | 60.5 ± 5.0 | +9.3 | <0.001 |

| 85 questions | 100 | 51.0 ± 5.7 | 60.4 ± 4.8 | +9.4 | <0.001 |

| Examination Length | N per LLM | ChatGPT Passing Rate (%) | Gemini Passing Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 questions | 100 | 14% | 59% |

| 35 questions | 100 | 11% | 57% |

| 45 questions | 100 | 10% | 55% |

| 55 questions | 100 | 8% | 52% |

| 65 questions | 100 | 6% | 51% |

| 75 questions | 100 | 5% | 50% |

| 85 questions | 100 | 4% | 49% |

| Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 215.40 | 6 | 35.90 | 3.67 | 0.0014 |

| Within groups | 6775.72 | 693 | 9.78 | — | — |

| Total | 6991.12 | 699 | — | — | — |

| Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 178.92 | 6 | 29.82 | 2.94 | 0.008 |

| Within groups | 7027.31 | 693 | 10.14 | — | — |

| Total | 7206.23 | 699 | — | — | — |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM type | 1452.80 | 1 | 1452.80 | 118.05 | <0.001 |

| Question count | 312.42 | 6 | 52.07 | 4.23 | 0.0003 |

| Interaction | 87.36 | 6 | 14.56 | 1.18 | 0.31 (ns) |

| Residual | 17,053.52 | 1386 | 12.30 | — | — |

| Total | 18,806.10 | 1399 | — | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Azhari, A.A.; Ahmed, W.M.; Alhamadani, A.; Alfaraj, A.; Zhang, M.; Lu, C.-T. Assessing the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Answering Dental Caries Multiple-Choice Questions: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Google Gemini Language Models. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14020072

Azhari AA, Ahmed WM, Alhamadani A, Alfaraj A, Zhang M, Lu C-T. Assessing the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Answering Dental Caries Multiple-Choice Questions: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Google Gemini Language Models. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzhari, Amr Ahmed, Walaa Magdy Ahmed, Abdulaziz Alhamadani, Amal Alfaraj, Min Zhang, and Chang-Tien Lu. 2026. "Assessing the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Answering Dental Caries Multiple-Choice Questions: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Google Gemini Language Models" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14020072

APA StyleAzhari, A. A., Ahmed, W. M., Alhamadani, A., Alfaraj, A., Zhang, M., & Lu, C.-T. (2026). Assessing the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Answering Dental Caries Multiple-Choice Questions: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Google Gemini Language Models. Dentistry Journal, 14(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14020072