External Apical Root Resorption Following Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- P (Population): Patients with malocclusion in need of orthodontic treatment, regardless of age or gender.

- I (Intervention): Patients treated with clear aligners.

- C (Control): Patients treated by fixed orthodontic appliances.

- O (Outcome): External apical root resorption in the vertical dimension, measured in mm or % of baseline root length.

2.1. Outcome

2.2. Search Processing and Data Collection

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Quantitative Analysis

2.4.1. Heterogeneity Assessment

2.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

2.4.3. Subgroup Analysis

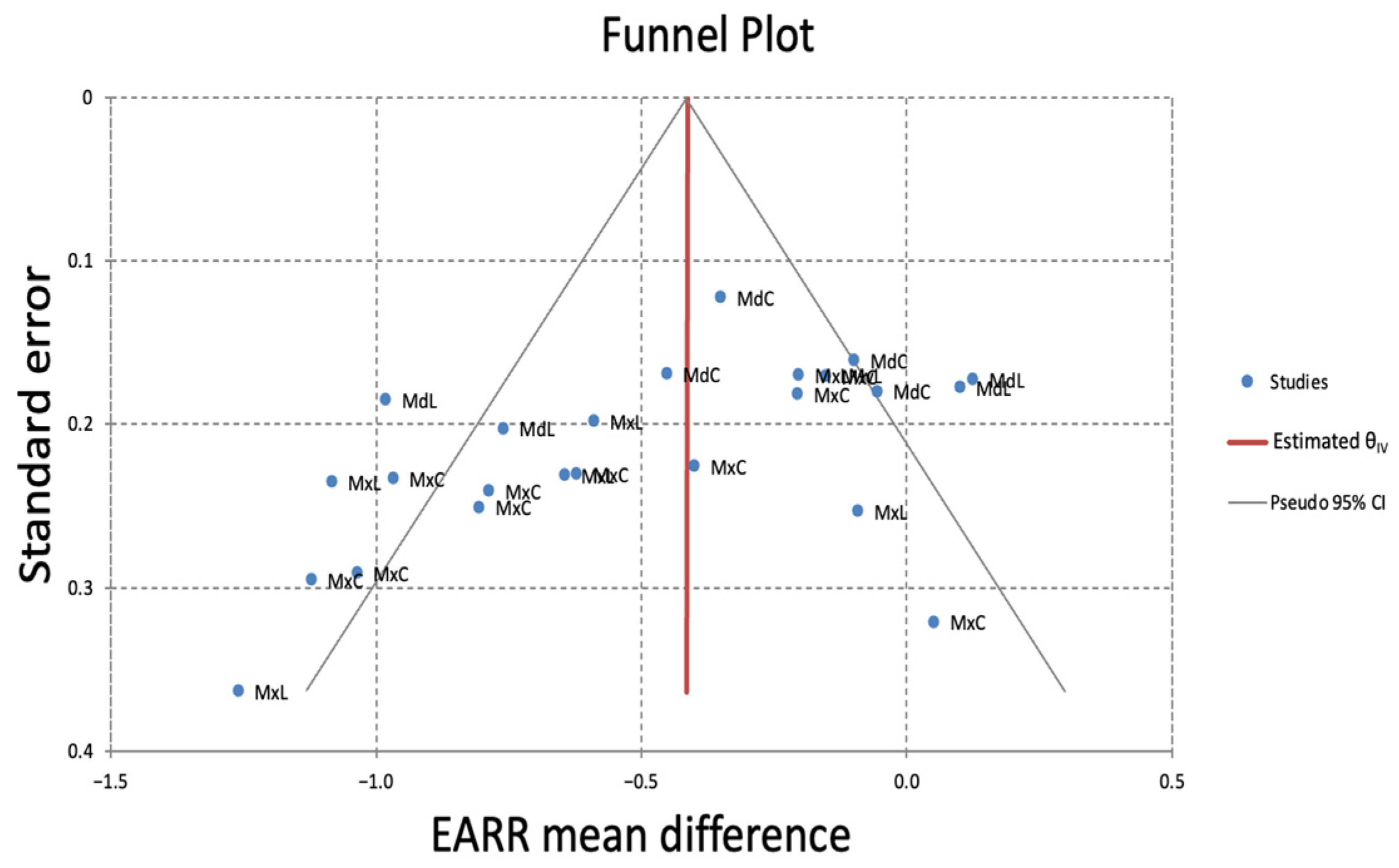

2.5. Assessment of Publication Bias

2.6. Assessment of the Overall Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.2. Meta-Analysis

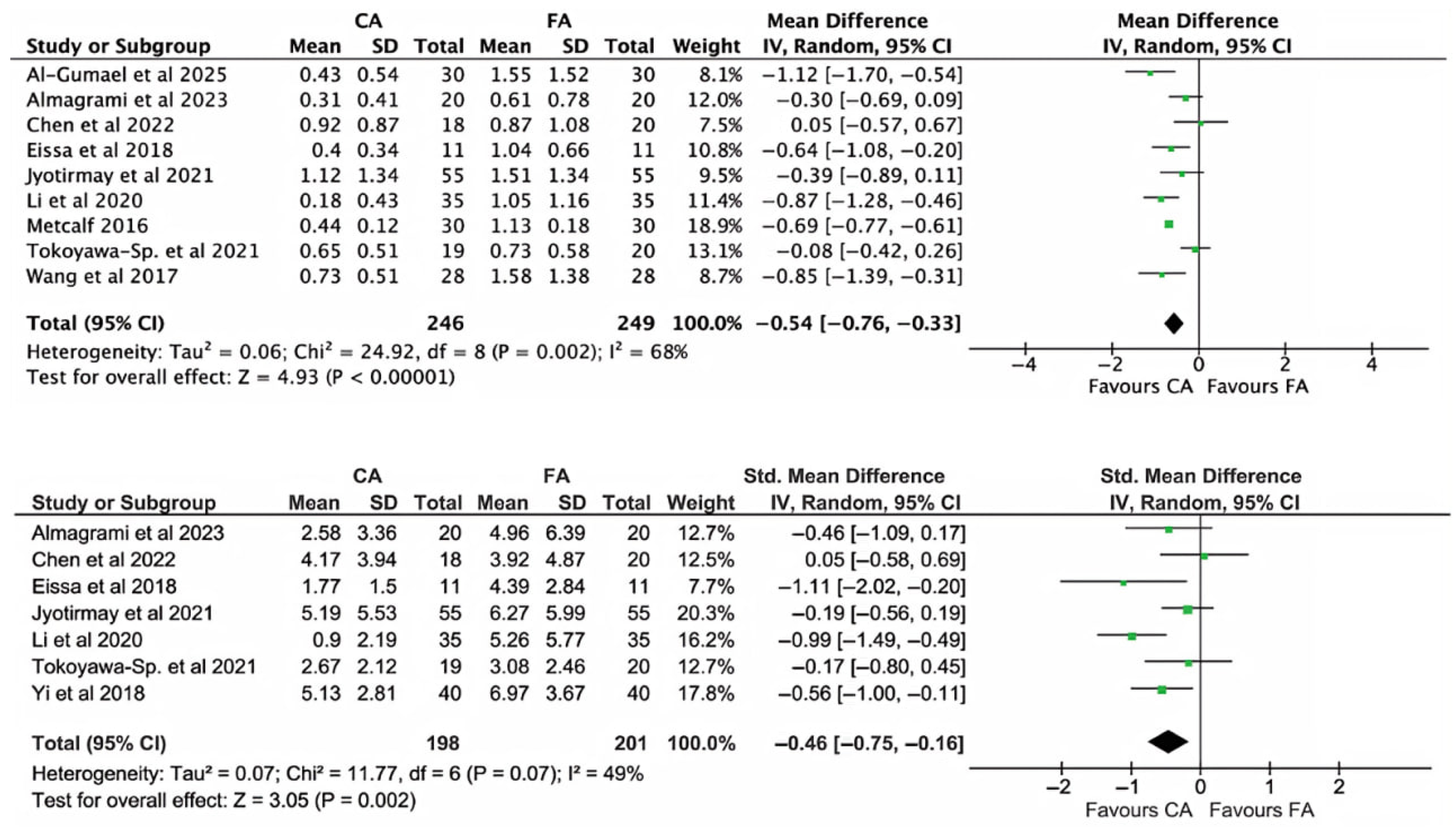

3.2.1. Overall Results for Incisor Teeth

3.2.2. Subgroup Analysis per Tooth Type

3.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

3.2.4. Subgroup Analysis Based on Tooth Extraction

3.2.5. Subgroup Analysis Based on Follow-Up Time

3.2.6. Subgroup Analysis Based on Radiographic Technique

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAs | Clear Aligners |

| FAs | Fixed Appliances |

| EARR | External Apical Root Resorption |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| MINORS | Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies |

| MxC | Maxillary Central Incisor |

| MxL | Maxillary Lateral Incisor |

| MdC | Mandibular Central Incisor |

| MdL | Mandibular Lateral Incisor |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

References

- Kuncio, D.; Maganzini, A.; Shelton, C.; Freeman, K. Invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment postretention outcomes compared using the American Board of Orthodontics objective grading system. Angle Orthod. 2007, 77, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameshima, G.T.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Orthodontic root resorption. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2021, 10, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z. External apical root resorption in non-extraction cases after clear aligner therapy or fixed orthodontic treatment. J. Dent. Sci. 2018, 13, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezniak, N.; Wasserstein, A. Root resorption after orthodontic treatment: Part 2. Literature review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1993, 103, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindaroglu, F.; Dogan, S. Root Resorption in Orthodontics. Turk. J. Orthod. 2016, 29, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgren, O.; Goldson, L.; Hill, C.; Orwin, A.; Petrini, L.; Lundberg, M. Root resorption after orthodontic treatment of traumatized teeth. Am. J. Orthod. 1982, 82, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maués, C.P.R.; do Nascimento, R.R.; de Vasconcellos Vilella, O. Severe root resorption resulting from orthodontic treatment: Prevalence and risk factors. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2015, 20, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltman, B.; Vig, K.W.L.; Fields, H.W.; Shanker, S.; Kaizar, E.E. Root resorption associated with orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, M.G.; Meira, J.B.C.; Cattaneo, P.M. Association of orthodontic force system and root resorption: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 147, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- das Neves, B.M.; Fernandes, L.Q.P.; Junior, J.C. External apical root resorption after orthodontic treatment: Analysis in different chronological periods. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2022, 27, e2220100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuabara, A. Biomechanical aspects of external root resorption in orthodontic therapy. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2007, 12, 610–613. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiuddin, S.; Yg, P.K.; Biswas, S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Bm, C.; Mp, R. Iatrogenic Damage to the Periodontium Caused by Orthodontic Treatment Procedures: An Overview. Open Dent. J. 2015, 9, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apajalahti, S.; Peltola, J.S. Apical root resorption after orthodontic treatment—A retrospective study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2007, 29, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Mei, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Prevalence and severity of apical root resorption during orthodontic treatment with clear aligners and fixed appliances: A cone beam computed tomography study. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kau, C.H.; Soh, J.; Christou, T.; Mangal, A. Orthodontic Aligners: Current Perspectives for the Modern Orthodontic Office. Medicina 2023, 59, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMogbel, A.M. Clear Aligner Therapy: Up to date review article. J. Orthod. Sci. 2023, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narongdej, P.; Hassanpour, M.; Alterman, N.; Rawlins-Buchanan, F.; Barjasteh, E. Advancements in Clear Aligner Fabrication: A Comprehensive Review of Direct-3D Printing Technologies. Polymers 2024, 16, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, M.J.; Ng, E.; Weir, T. Digital treatment planning and clear aligner therapy: A retrospective cohort study. J. Orthod. 2023, 50, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Jian, F.; McIntyre, G.T.; Millett, D.T.; Hickman, J.; Lai, W. Initial arch wires used in orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD007859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chainani, P.; Paul, P.; Shivlani, V. Recent Advances in Orthodontic Archwires: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e47633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundhada, V.V.; Jadhav, V.V.; Reche, A. A Review on Orthodontic Brackets and Their Application in Clinical Orthodontics. Cureus 2023, 15, e46615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagrami, I.; Almashraqi, A.A.; Almaqrami, B.S.; Mohamed, A.S.; Wafaie, K.; Al-Balaa, M.; Qiao, Y. A quantitative three-dimensional comparative study of alveolar bone changes and apical root resorption between clear aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. Prog. Orthod. 2023, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyokawa-Sperandio, K.C.; de Castro Ferreira Conti, A.C.; Fernandes, T.M.F.; de Almeida-Pedrin, R.R.; de Almeida, M.R.; Oltramari, P.V.P. External apical root resorption 6 months after initiation of orthodontic treatment: A randomized clinical trial comparing fixed appliances and orthodontic aligners. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyotirmay; Singh, S.K.; Adarsh, K.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.R.; Sinha, A. Comparison of Apical Root Resorption in Patients Treated with Fixed Orthodontic Appliance and Clear Aligners: A Cone-beam Computed Tomography Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, O.; Carlyle, T.; El-Bialy, T. Evaluation of root length following treatment with clear aligners and two different fixed orthodontic appliances. A pilot study. J. Orthod. Sci. 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.; Mathelié-Guinlet, Q.; Ramires, F.; Monteiro, F.; Carvalho, Ó.; Silva, F.S.; Resende, A.D.; Pinho, T. Biological alterations associated with the orthodontic treatment with conventional appliances and aligners: A systematic review of clinical and preclinical evidence. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandesan, H.; Ravanmehr, H.; Valaei, N. A radiographic analysis of external apical root resorption of maxillary incisors during active orthodontic treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 2007, 29, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocadereli, I.; Yesil, T.N.; Veske, P.S.; Uysal, S. Apical Root Resorption: A Prospective Radiographic Study of Maxillary Incisors. Eur. J. Dent. 2011, 5, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Koletsi, D.; Iliadi, A.; Peltomaki, T.; Eliades, T. Treatment outcome with orthodontic aligners and fixed appliances: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsheid, R.; Godoy, L.D.C.; Kuo, C.-L.; Metz, J.; Dolce, C.; Abu Arqub, S. Comparative assessment of the clinical outcomes of clear aligners compared to fixed appliance in class II malocclusion. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, H.S.; Berrier, J.; Reitman, D.; Ancona-Berk, V.; Chalmers, T.C. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 316, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-G.; Peace, K.E. Applied Meta-Analysis with R and Stata; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.; Lau, J. Pooling research results: Benefits and limitations of meta-analysis. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 1999, 25, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Altman, D.G. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context; BMJ Publishing Group: London, UK, 2006; p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions|Cochrane Training. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abariga, S.A.; McCaul, M.; Musekiwa, A.; Ochodo, E.; Rohwer, A. Evidence-Informed Public Health, Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 89–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Phillips, A.N. Meta-analysis: Principles and procedures. BMJ 1997, 315, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Gumaei, W.S.; Long, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, G.; Lai, W.; Jian, F. Three-dimensional comparative analysis of upper central incisors external apical root resorption/ incisive canal changes in first premolar extraction cases: Clear aligners Versus passive self-ligating fixed braces. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Han, M.; Gu, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Pan, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, W.; et al. Changes of maxillary central incisor and alveolar bone in Class II Division 2 nonextraction treatment with a fixed appliance or clear aligner: A pilot cone-beam computed tomography study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 163, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, T.J. Comparison of External Apical Root Resorption in Class I Subjects Treated with Invisalign and Conventional Orthodontics: A CBCT Analysis. PhD Thesis, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Luo, S.-L.; Zheng, J.-W. A retrospective study on incisor root resorption in patients treated with bracketless invisible appliance and straight wire appliance. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 2017, 26, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Abass, S.K.; Hartsfield, J.K. Orthodontics and External Apical Root Resorption. Semin. Orthod. 2007, 13, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Qi, R.; Liu, C. Root resorption in orthodontic treatment with clear aligners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2019, 22, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinatoa, J.A.Y.; Leung, W.L.Á.; Villacis, P.J.S. Interpretation of the Comparison of Root Resorption Between Dental Aligners and Fixed Appliances by Literature Review. J. Adv. Zool. 2023, 44, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassir, Y.A.; Nabbat, S.A.; McIntyre, G.T.; Bearn, D.R. Clinical effectiveness of clear aligner treatment compared to fixed appliance treatment: An overview of systematic reviews. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2022, 26, 2353–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Jain, R.K.; Balasubramaniam, A. Comparative assessment of external apical root resorption between subjects treated with clear aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2024, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhaddaoui, R.; Qoraich, H.S.; Bahije, L.; Zaoui, F. Orthodontic aligners and root resorption: A systematic review. Int. Orthod. 2017, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zainal, M.H.; Anvery, S.; Al-Jewair, T. Clear Aligner Therapy May Not Prevent but May Decrease the Incidence of External Root Resorption Compared to Full Fixed Appliances. J. Évid. Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadauskienė, U.; Berlin, V. Orthodontic treatment with clear aligners and apical root resorption. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, V.; Mehta, S.; Gauthier, M.; Mu, J.; Kuo, C.-L.; Nanda, R.; Yadav, S. Comparison of external apical root resorption with clear aligners and pre-adjusted edgewise appliances in non-extraction cases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 43, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, M.; Nivethitha, B.; Madhan, B. Orthodontically induced external apical root resorption with clear aligners compared to fixed appliance treatment: An umbrella review. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2025, 15, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Fiore, A.; Balestriere, L.; Nardelli, P.; Casamassima, L.; Di Venere, D.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M. The Differential Impact of Clear Aligners and Fixed Orthodontic Appliances on Periodontal Health: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, Y.-I. Multi-step finite element simulation for clear aligner space closure: A proof-of-concept compensation protocol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Davidovitch, Z. Cellular, molecular, and tissue-level reactions to orthodontic force. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 469.e1–469.e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toyokawa-Sperandio (2021) [23] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Darvizeh, A.; González Sánchez, J.A.; Doria Jaureguizar, G.; Quevedo, O.; de la Iglesia Beyme, F.; Elmsmari, F.; Del Fabbro, M. External Apical Root Resorption Following Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120580

Darvizeh A, González Sánchez JA, Doria Jaureguizar G, Quevedo O, de la Iglesia Beyme F, Elmsmari F, Del Fabbro M. External Apical Root Resorption Following Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):580. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120580

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarvizeh, Atanaz, José Antonio González Sánchez, Guillermo Doria Jaureguizar, Oriol Quevedo, Fernando de la Iglesia Beyme, Firas Elmsmari, and Massimo Del Fabbro. 2025. "External Apical Root Resorption Following Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120580

APA StyleDarvizeh, A., González Sánchez, J. A., Doria Jaureguizar, G., Quevedo, O., de la Iglesia Beyme, F., Elmsmari, F., & Del Fabbro, M. (2025). External Apical Root Resorption Following Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120580