Computational Insights into Root Canal Treatment: A Survey of Selected Methods in Imaging, Segmentation, Morphological Analysis, and Clinical Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

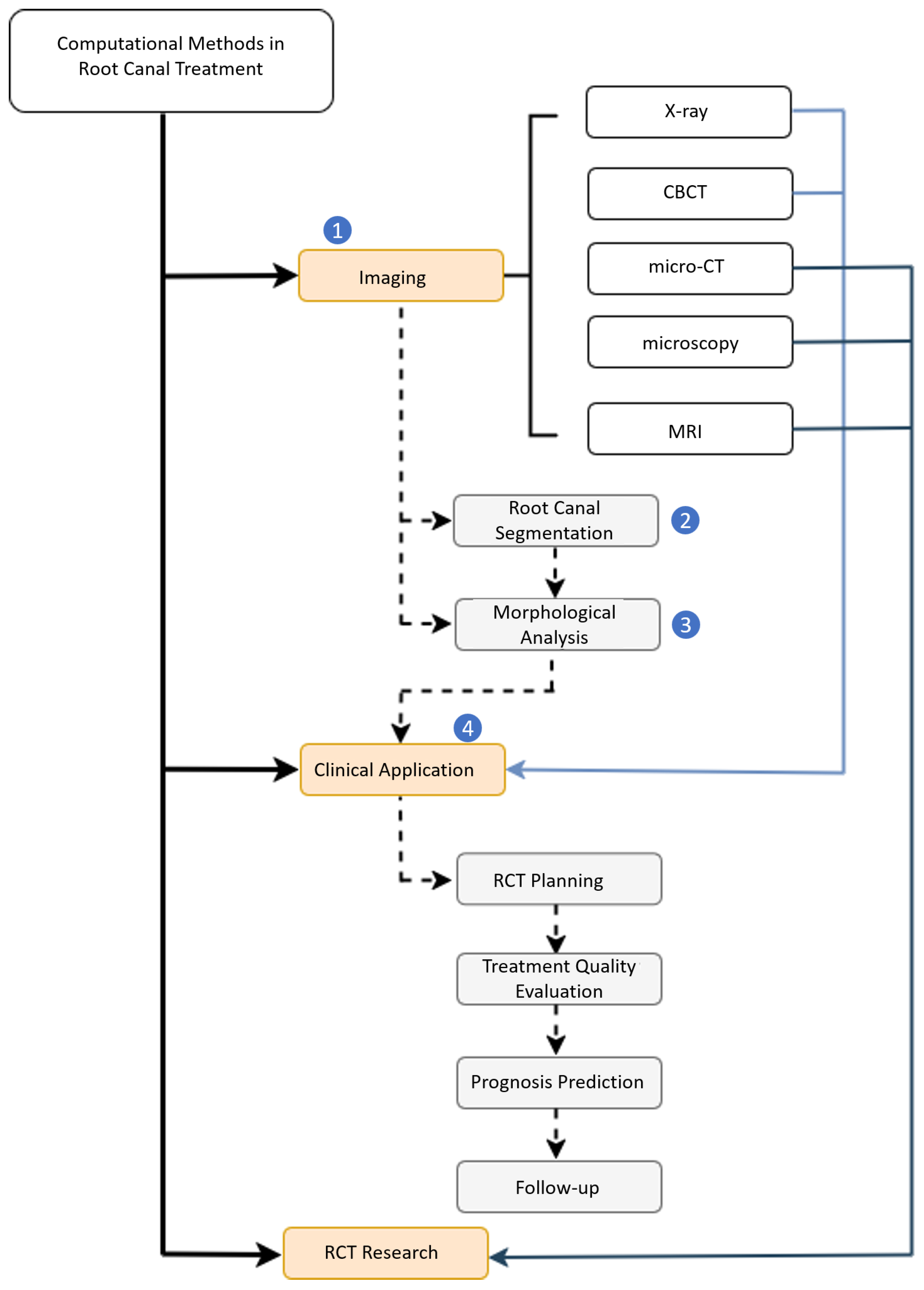

1.1. Taxonomy

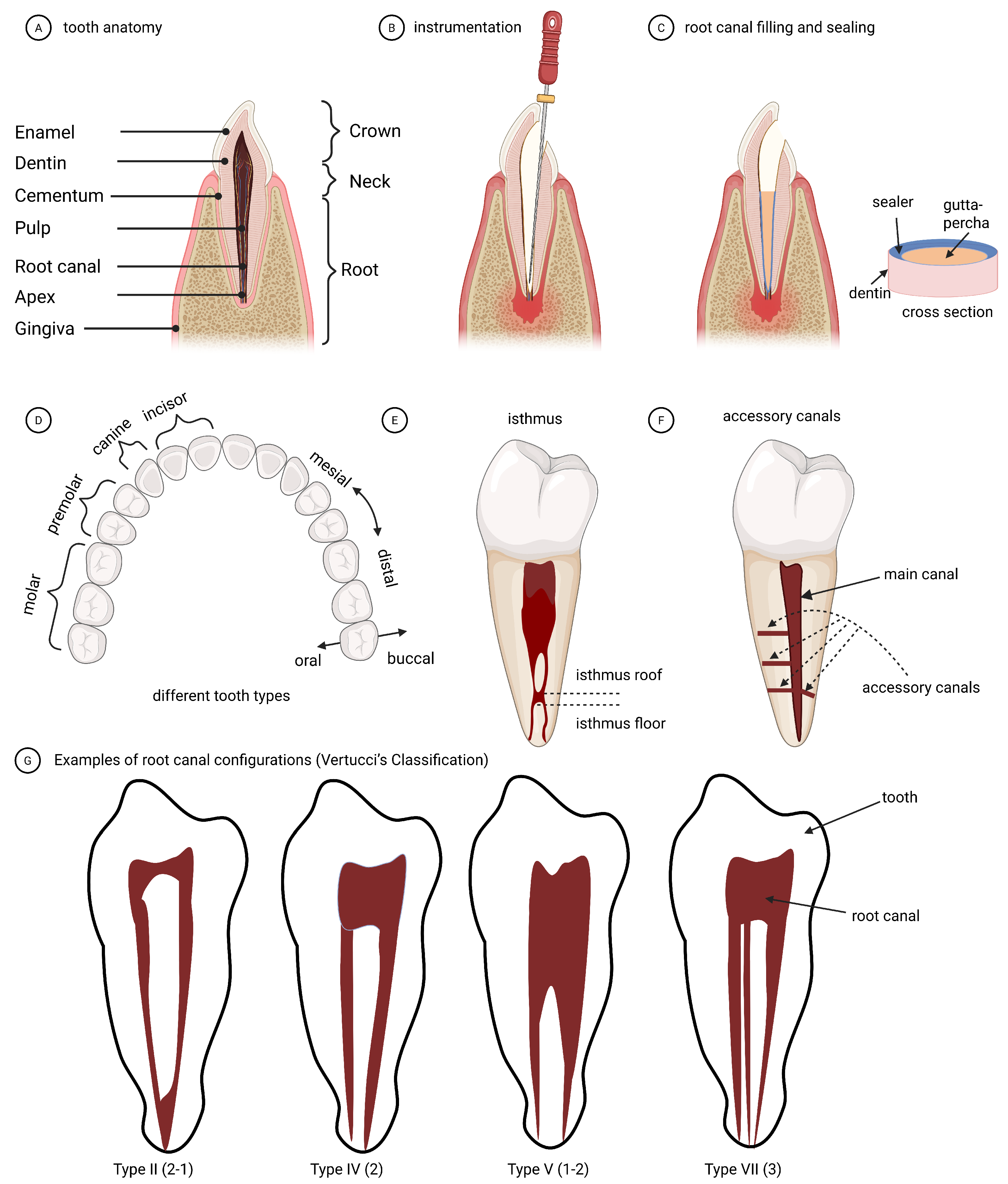

1.2. Dental Terminologies

1.3. Manuscript Outline

1.4. Search Strategy and Scope of Review

2. Dental Imaging in Root Canal Treatment

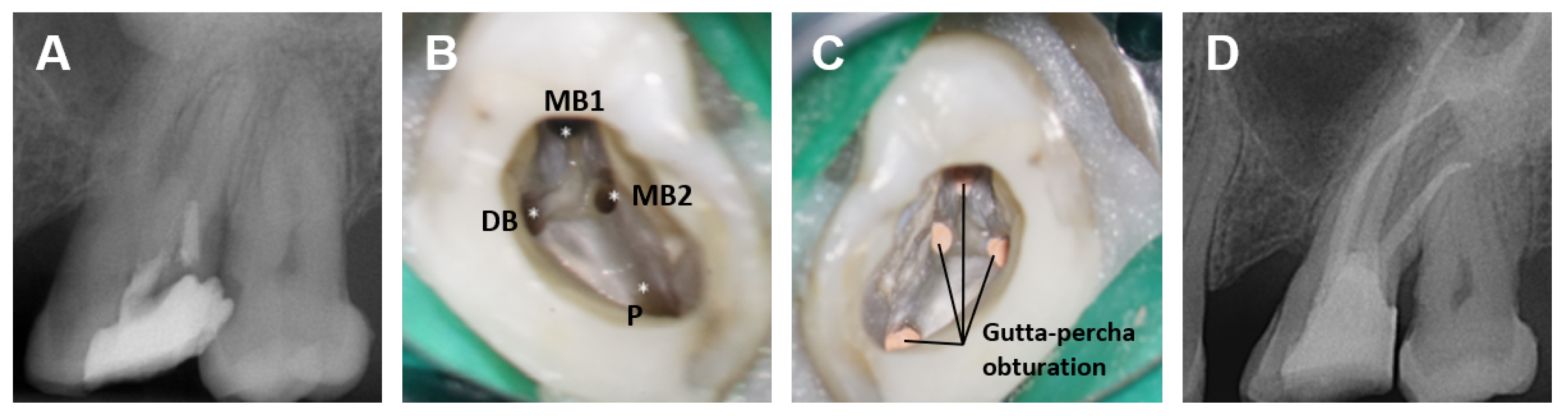

2.1. Root Canal Treatment

2.2. Dental Imaging in RCT Clinical Routine

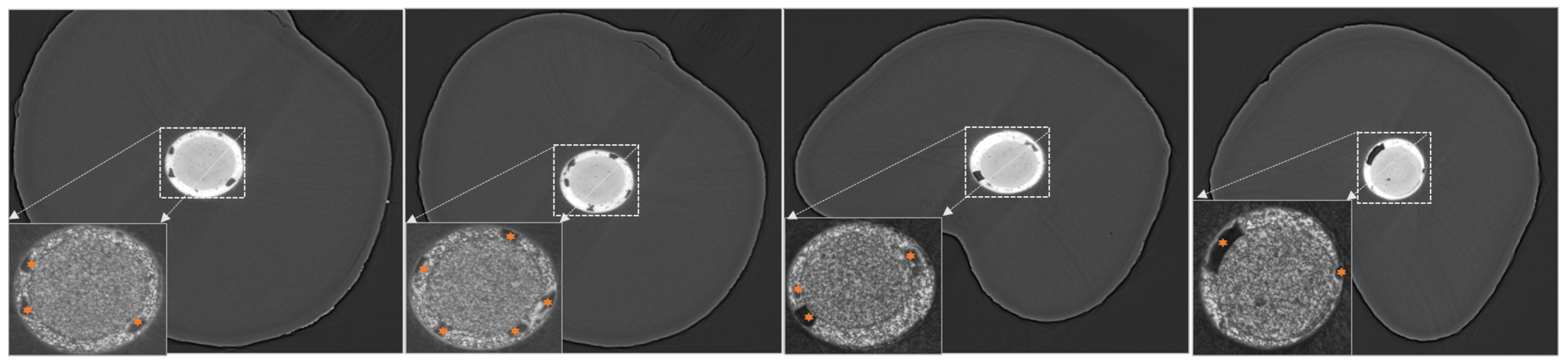

2.3. Dental Imaging in RCT Research and Education

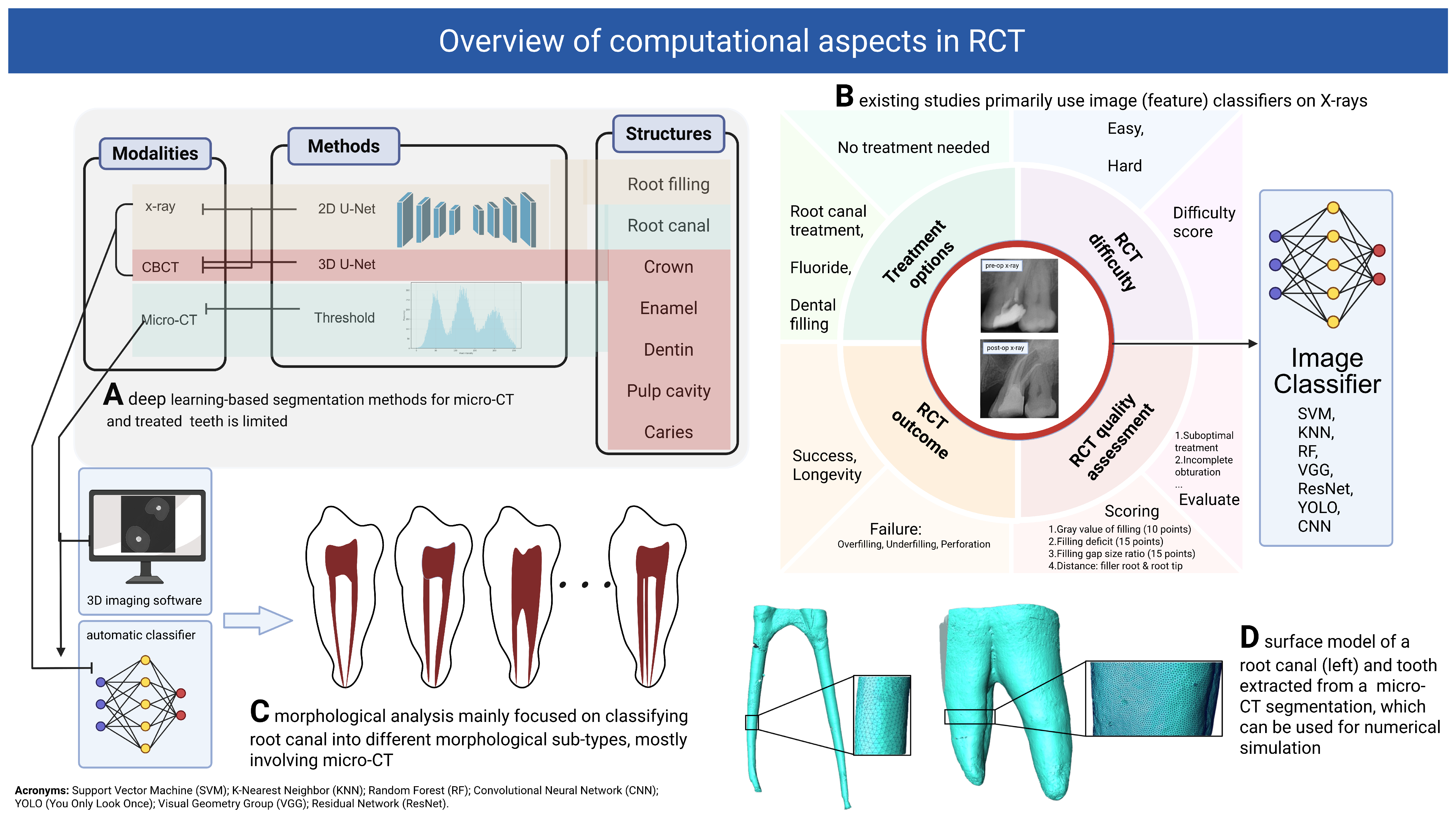

3. Computational Approaches in Root Canal Treatment: A Review of Methods

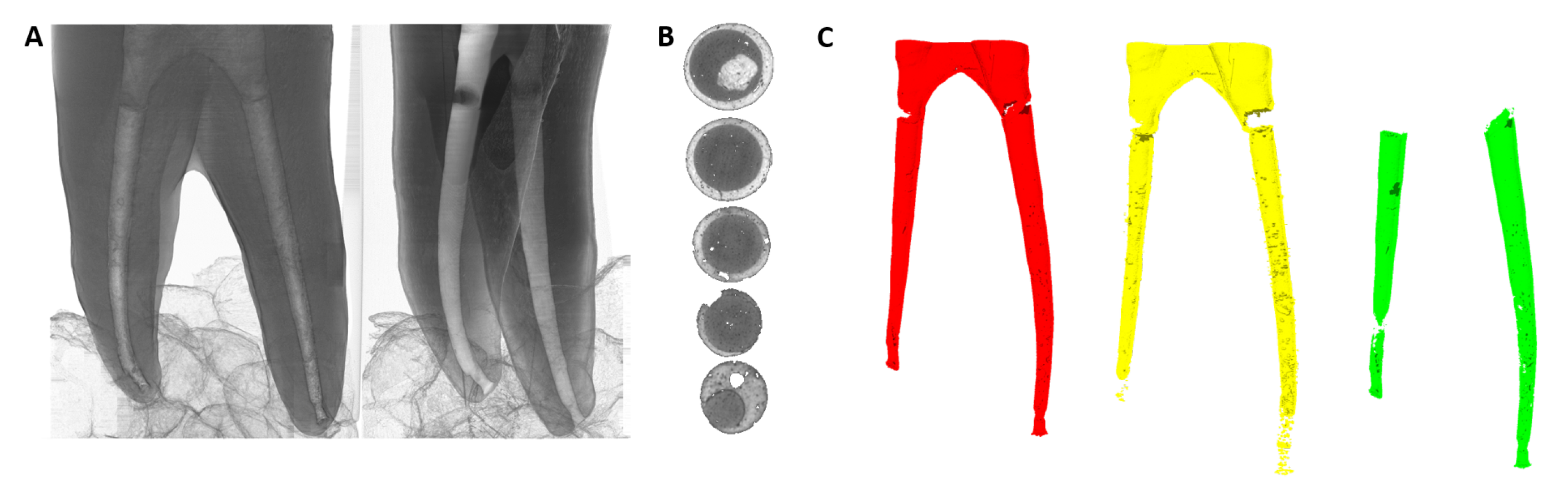

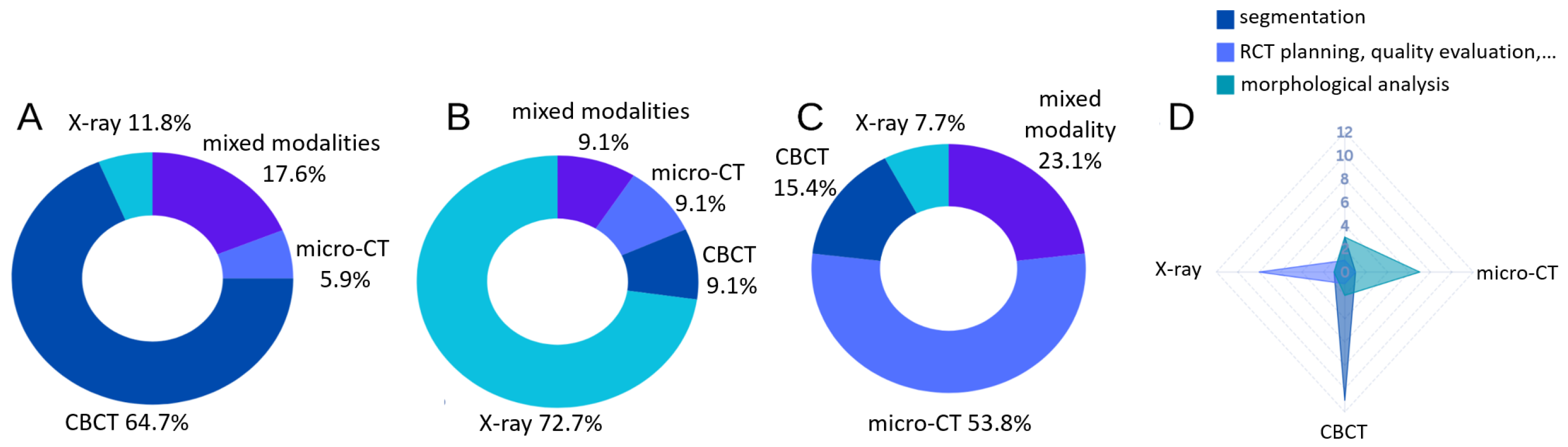

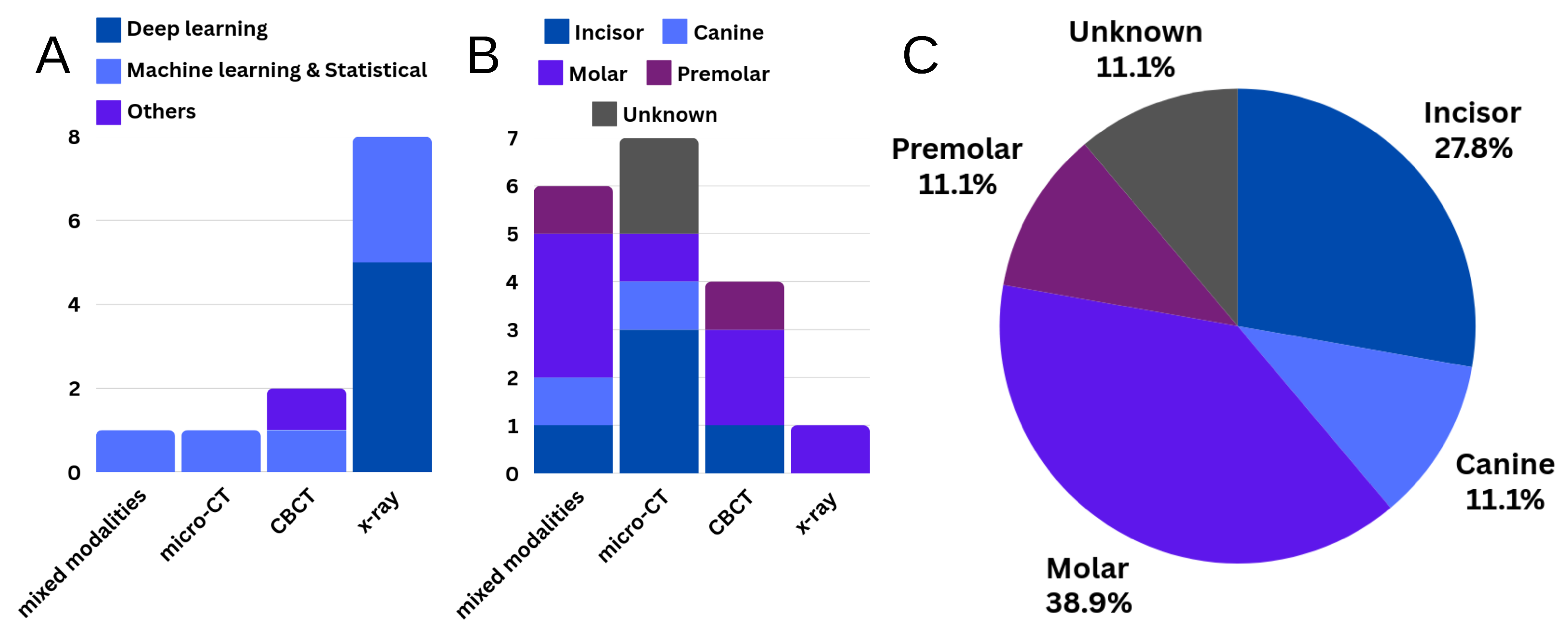

3.1. Segmentation

3.1.1. Joint Segmentation of Tooth and Its Sub-Structures

3.1.2. Root Canal Segmentation

3.2. Treatment Planning, Quality Evaluation and Prognosis

3.2.1. Treatment Planning and Recommendation

3.2.2. RCT Quality Evaluation, Outcome Prediction, Prognosis and Follow-Ups

3.3. Morphological Analysis

3.3.1. Root Canal Morphology Classification and Measurements

3.3.2. Super-Resolution

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Current State

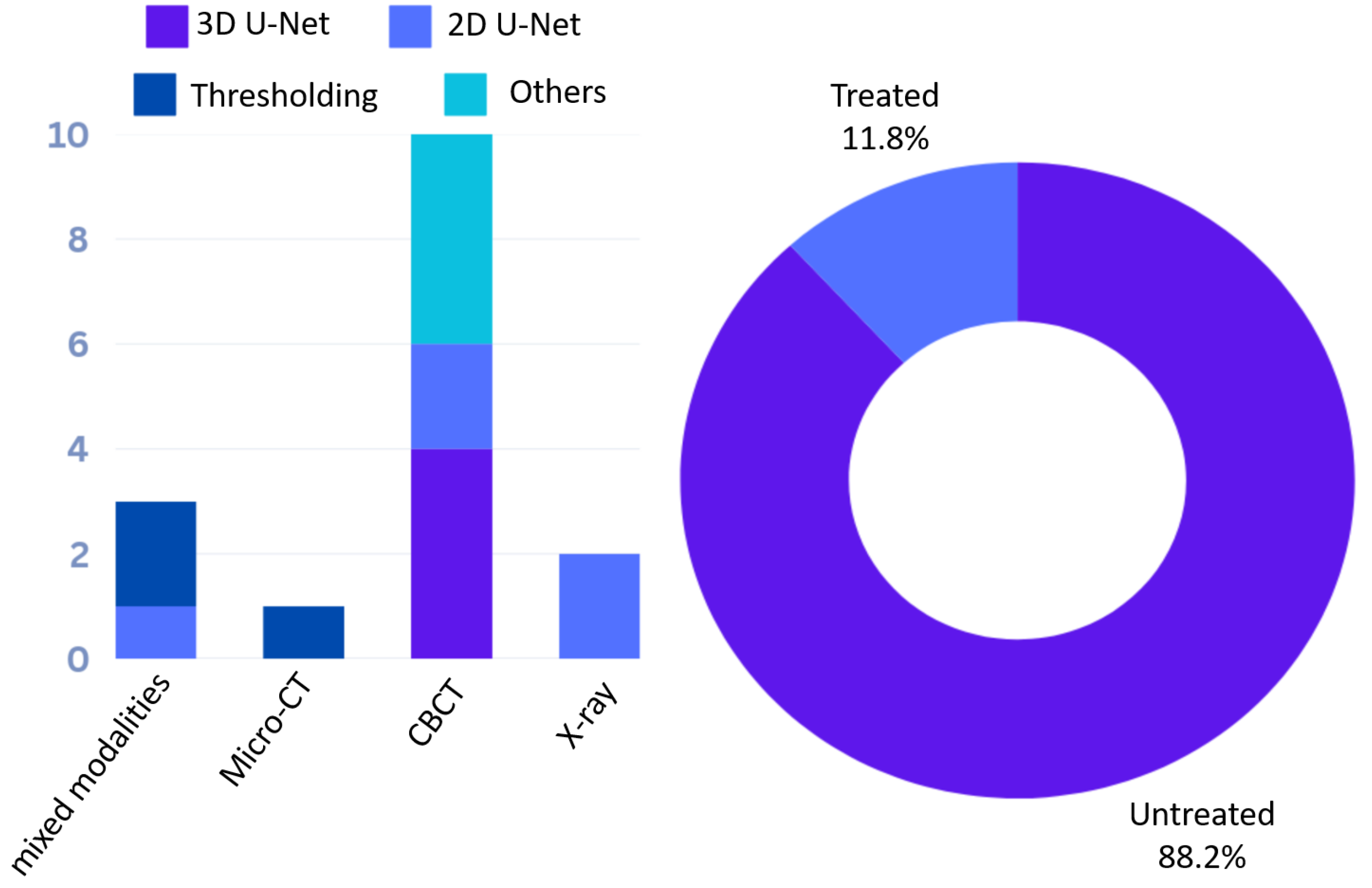

4.1.1. Segmentation

4.1.2. Treatment Planing, Quality Evaluation and Prognosis

4.1.3. Morphological Analysis

4.1.4. Critical Evaluation

4.2. Future Direction, Challenges and Practical Recommendation

4.2.1. Defect Detection and Classification

4.2.2. Micro-CT Based Segmentation

4.2.3. Explicit, Learning-Based Morphological Analysis

4.2.4. Translation of Research Insights into Clinical Practice

4.2.5. Overview of Computational Tools and Software

4.2.6. Manuscript Preparation

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duncan, H.F.; Kirkevang, L.L.; Peters, O.A.; El-Karim, I.; Krastl, G.; Del Fabbro, M.; Chong, B.S.; Galler, K.M.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Kebschull, M.; et al. Treatment of pulpal and apical disease: The European Society of Endodontology (ESE) S3-level clinical practice guideline. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 238–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayat, A.; Lee, S.J.; Torabinejad, M. Human saliva penetration of coronally unsealed obturated root canals. J. Endod. 1993, 19, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chevigny, C.; Dao, T.T.; Basrani, B.R.; Marquis, V.; Farzaneh, M.; Abitbol, S.; Friedman, S. Treatment outcome in endodontics: The Toronto study—Phase 4: Initial treatment. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamira, A.; Mazzi-Chaves, J.F.; Nicolielo, L.F.P.; Leoni, G.B.; Silva-Sousa, A.C.; Silva-Sousa, Y.T.C.; Pauwels, R.; Buls, N.; Jacobs, R.; Sousa-Neto, M.D. CBCT-based assessment of root canal treatment using micro-CT reference images. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2022, 52, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, P.; Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, J.; Ma, J. Identification of root canal morphology in fused-rooted mandibular second molars from X-Ray images based on deep learning. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 1289–1297.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Fu, Y.; Ren, G.; Yang, X.; Duan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q. Micro–computed tomography–guided artificial intelligence for pulp cavity and tooth segmentation on cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.; Díaz-Flores García, V.; Algar, J.; Gómez Sánchez, M.; Llorente de Pedro, M.; Freire, Y. Unveiling the ChatGPT phenomenon: Evaluating the consistency and accuracy of endodontic question answers. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.T.; Huang, H.Y.; Lee, T.M.; Sung, T.Y.; Yang, C.H.; Kuo, Y.M. Predicting root fracture after root canal treatment and crown installation using deep learning. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.K.; Zhu, M.; AlHadidi, A.; Wang, C.; Hung, K.; Wohlgemuth, P.; Lam, W.Y.H.; Liu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, H. A novel AI model for detecting periapical lesion on CBCT: CBCT-SAM. J. Dent. 2025, 153, 105526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Neto, M.D.d.; Silva-Sousa, Y.C.; Mazzi-Chaves, J.F.; Carvalho, K.K.T.; Barbosa, A.F.S.; Versiani, M.A.; Jacobs, R.; Leoni, G.B. Root canal preparation using micro-computed tomography analysis: A literature review. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, A.M.; Thakur, B.; Kfir, A.; Kim, H.C. Dentinal defects induced by 6 different endodontic files when used for oval root canals: An in vitro comparative study. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2019, 44, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Pirri, R.; Alibrandi, A.; Pulvirenti, D.; Simeone, M. Comparison of Four Ni-Ti Rotary Systems: Dental Students’ Perceptions in a Multi-Center Simulated Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Mahajan, P.; Thaman, D.; Monga, P. Comparison of dentinal damage induced by different nickel-titanium rotary instruments during canal preparation: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2015, 18, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, P.; Bajaj, N.; Mahajan, P.; Garg, S. Comparison of incidence of dentinal defects after root canal preparation with continuous rotation and reciprocating instrumentation. Singap. Dent. J. 2015, 36, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulabivala, K.; Ng, Y.L. Factors that affect the outcomes of root canal treatment and retreatment—A reframing of the principles. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y. Treatment strategy of lateral canals during root canal therapy. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi Zhonghua Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi Chin. J. Stomatol. 2023, 58, 958–963. [Google Scholar]

- Hidetaka, I.; Shizuka, Y.; Atsutoshi, Y. Overview of Lateral Canals in Endodontic Treatment and Its Treatment Strategies. Jpn. J. Conserv. Dent. 2022, 65, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tulus, G.; Weber, T.; Petrovits, A. Diagnosis and therapy of branched Root Canal Systems. ENDO 2015, 9, 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Jung, H.; Kim, S.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, E. The influence of an isthmus on the outcomes of surgically treated molars: A retrospective study. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.B.; Georgiou, A.; Diogo, P.; de Vries, R.; Freixo, V.; Palma, P.; Shemesh, H. CBCT-Assessed Outcomes and Prognostic Factors of Primary Endodontic Treatment and Retreatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Endod. 2025, 51, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, N.S.; Alamoudi, R.A.; Baba, S.M.; Mattoo, K.; Hawi, R.H.A.; Ali, W.N.; Almadhlami, N.M.H.; Lahiq, A.M.A. A scanning electron microscopy study comparing 3 obturation techniques to seal dentin to root canal bioceramic sealer in 30 freshly extracted mandibular second premolars. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2023, 29, e940599-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celikten, B.; Uzuntas, C.F.; Orhan, A.I.; Tufenkci, P.; Misirli, M.; Demiralp, K.O.; Orhan, K. Micro-CT assessment of the sealing ability of three root canal filling techniques. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 57, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinzadeh, A.T.; Farack, L.; Wilde, F.; Shemesh, H.; Zaslansky, P. Synchrotron-based phase contrast-enhanced micro–computed tomography reveals delaminations and material tearing in water-expandable root fillings ex vivo. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, N.; Keleş, A.; Ahmetoglu, F.; Akıncı, L.; Er, K. 3D Micro-CT analysis of void and gap formation in curved root canals. Eur. Endod. J. 2017, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArRejaie, A.; Alsuliman, S.A.; Aljohani, M.O.; Altamimi, H.A.; Alshwaimi, E.; Al-Thobity, A.M. Micro-computed tomography analysis of gap and void formation in different prefabricated fiber post cementation materials and techniques. Saudi Dent. J. 2019, 31, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timme, M.; Masthoff, M.; Nagelmann, N.; Masthoff, M.; Faber, C.; Bürklein, S. Imaging of root canal treatment using ultra high field 9.4 T UTE-MRI—A preliminary study. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2020, 49, 20190183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberthür, D.; Hlushchuk, R.; Wolf, T.G. Automated segmentation and description of the internal morphology of human permanent teeth by means of micro-CT. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michetti, J.; Basarab, A.; Diemer, F.; Kouame, D. Comparison of an adaptive local thresholding method on CBCT and μCT endodontic images. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 63, 015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petryniak, R.; Tabor, Z.; Kierklo, A.; Jaworska, M. Detection of voids of dental root canal obturation using micro-CT. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Graphics: International Conference, ICCVG 2012, Warsaw, Poland, 24–26 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib, I.; Wong, F.S.; Davis, G.R. A Protocol for Void Detection in Root-Filled Teeth Using Micro-CT: Ex-Vivo. Eur. Endod. J. 2025, 10, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, K.; Jacobs, R.; Celikten, B.; Huang, Y.; de Faria Vasconcelos, K.; Nicolielo, L.F.P.; Buyuksungur, A.; Van Dessel, J. Evaluation of threshold values for root canal filling voids in micro-CT and nano-CT images. Scanning 2018, 2018, 9437569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Lizio, A.S.; Coppini, V.; Lo Giudice, R.; Lo Giudice, G. CBCT-based assessment of vapor lock effects on endodontic disinfection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, S.; Venkata Teja, K.; Ramesh, S.; Jose, J.; Cernera, M.; Soltani, P.; Nogueira Leal da Silva, E.J.; Spagnuolo, G. Assessment of Anatomical Dentin Thickness in Mandibular First Molar: An In Vivo Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 8823070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.H.; Li, G.; Shemesh, H.; Wesselink, P.R.; Wu, M.K. The association between complete absence of post-treatment periapical lesion and quality of root canal filling. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, D.; Kharouf, N.; Hemmerlé, J.; Haïkel, Y. Microscopic and chemical assessments of the filling ability in oval-shaped root canals using two different carrier-based filling techniques. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva-Goig, R.; Forner-Navarro, L.; Llena-Puy, M.C. Microscopic assessment of the sealing ability of three endodontic filling techniques. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dada, A.; Puladi, B.; Kleesiek, J.; Egger, J. ChatGPT in healthcare: A taxonomy and systematic review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 245, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Barai, S.; Kumar, R.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Maity, A.B.; Shankarappa, P. Comparative evaluation of incidence of dentinal defects after root canal preparation using hand, rotary, and reciprocating files: An ex vivo study. J. Int. Oral Health 2022, 14, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, H.; Roeleveld, A.C.; Wesselink, P.R.; Wu, M.K. Damage to root dentin during retreatment procedures. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.A.; Doumani, M.D.; Nassani, M.Z.; Shamsy, E.; Jto, B.S.; Arwadi, H.A.; Mohamed, S.A. Radiographic assessment of the quality of root canal fillings performed by senior dental students. Eur. Endod. J. 2018, 3, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Liu, J.; Yan, F.; Liu, B. An Evaluation Method of Dental Treatment Quality Combined with Deep Learning and Multi-index Decomposition. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 2351714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, G.; Yan, S. An intelligent evaluation method of root canal therapy quality based on deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25–27 November 2022; pp. 6254–6259. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, H.; Shetty, S.; Kakade, A.; Shetty, A.; Karobari, M.I.; Pawar, A.M.; Marya, A.; Heboyan, A.; Venugopal, A.; Nguyen, T.H.; et al. Three-dimensional semi-automated volumetric assessment of the pulp space of teeth following regenerative dental procedures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Zheng, Y. 3D tooth segmentation and labeling using deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2018, 25, 2336–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.H.; Lian, C.; Lee, S.; Pastewait, M.; Piers, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Chiu, C.Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Two-stage mesh deep learning for automated tooth segmentation and landmark localization on 3D intraoral scans. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 3158–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, F.; Lumetti, L.; Vinayahalingam, S.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Pellacani, A.; Marchesini, K.; Van Nistelrooij, N.; Van Lierop, P.; Xi, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Segmenting the Inferior Alveolar Canal in CBCTs Volumes: The ToothFairy Challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 44, 1890–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, E.; Leite, A.; Alqahtani, K.A.; Smolders, A.; Van Gerven, A.; Willems, H.; Jacobs, R. A novel deep learning system for multi-class tooth segmentation and classification on cone beam computed tomography. A validation study. J. Dent. 2021, 115, 103865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Alqahtani, K.A.; Van den Bogaert, T.; Shujaat, S.; Jacobs, R.; Shaheen, E. Convolutional neural network for automated tooth segmentation on intraoral scans. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, B.; Shen, Y.; Shen, K. TeethGNN: Semantic 3D teeth segmentation with graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 29, 3158–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillot, M.; Baquero, B.; Le, C.; Deleat-Besson, R.; Bianchi, J.; Ruellas, A.; Gurgel, M.; Yatabe, M.; Al Turkestani, N.; Najarian, K.; et al. Automatic multi-anatomical skull structure segmentation of cone-beam computed tomography scans using 3D UNETR. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.; Yuh, D.Y.; Lin, S.C.; Lyu, P.S.; Pan, G.X.; Zhuang, Y.C.; Chang, C.C.; Peng, H.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Juan, C.H.; et al. Improving performance of deep learning models using 3.5 D U-Net via majority voting for tooth segmentation on cone beam computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, K.; Han, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, J. Automatic tooth roots segmentation of cone beam computed tomography image sequences using U-net and RNN. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2020, 28, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Du, H.; Yun, Z.; Yang, S.; Dai, Z.; Zhong, L.; Feng, Q.; Yang, W. Automatic segmentation of individual tooth in dental CBCT images from tooth surface map by a multi-task FCN. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 97296–97309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelsea Wang, Y.C.; Chen, T.L.; Vinayahalingam, S.; Wu, T.H.; Chang, C.W.; Hao Chang, H.; Wei, H.J.; Chen, M.H.; Ko, C.C.; Anssari Moin, D.; et al. Artificial Intelligence to Assess Dental Findings from Panoramic Radiographs—A Multinational Study. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.10277. [Google Scholar]

- Ourang, S.A.; Sohrabniya, F.; Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Dianat, O.; Aminoshariae, A.; Nagendrababu, V.; Dummer, P.M.H.; Duncan, H.F.; Nosrat, A. Artificial intelligence in endodontics: Fundamental principles, workflow, and tasks. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1546–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleat-Besson, R.; Le, C.; Al Turkestani, N.; Zhang, W.; Dumont, M.; Brosset, S.; Prieto, J.C.; Cevidanes, L.; Bianchi, J.; Ruellas, A.; et al. Automatic segmentation of dental root canal and merging with crown shape. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 2948–2951. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, M.; Prieto, J.C.; Brosset, S.; Cevidanes, L.; Bianchi, J.; Ruellas, A.; Gurgel, M.; Massaro, C.; Del Castillo, A.A.; Ioshida, M.; et al. Patient specific classification of dental root canal and crown shape. In Shape in Medical Imaging: International Workshop, ShapeMI 2020, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2020, Lima, Peru, October 4, 2020, Proceedings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, W.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Bian, X.; Liu, C.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Tang, Z. Root canal treatment planning by automatic tooth and root canal segmentation in dental CBCT with deep multi-task feature learning. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 85, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, X.; Yang, X. Refined tooth and pulp segmentation using U-Net in CBCT image. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2021, 50, 20200251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, W.; Dong, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Root canal segmentation in cbct images by 3d u-net with global and local combination loss. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 3097–3100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Du, Y.; Ye, L.; Li, C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, W. Teeth and Root Canals Segmentation using Zxyformer with Uncertainty Guidance and Weight Transfer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Cartagena, Colombia, 18–21 April 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Xie, Z. Deep learning in cone-beam computed tomography image segmentation for the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulpitis. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 11245–11264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Harris, L.; Harrison, J.; Schmittbuhl, M.; De Guise, J. Automatic Pulp and Teeth Three-Dimensional Modeling of Single and Multi-Rooted Teeth Based on Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Imaging: A Promising Approach With Clinical and Therapeutic Outcomes. Cureus 2023, 15, e38066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Cui, Z.; Zhong, T.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, D. A progressive framework for tooth and substructure segmentation from cone-beam CT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 169, 107839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, J.F.; Pires, P.M.; dos Santos, T.M.P.; de Almeida Neves, A.; Lopes, R.T.; Visconti, M.A.P.G. Root canal segmentation in cone-beam computed tomography: Comparison with a micro-CT gold standard. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 18, e191627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, T.; Sağlam, H.; Öksüzoğlu, H.; Kazan, O.; Bayrakdar, İ.Ş.; Duman, S.B.; Çelik, Ö.; Jagtap, R.; Futyma-Gąbka, K.; Różyło-Kalinowska, I.; et al. Automatic feature segmentation in dental periapical radiographs. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiyanoğlu, E.; Ünsal, G.; Akkaya, N.; Aksoy, S.; Orhan, K. Automatic segmentation of teeth, crown–bridge restorations, dental implants, restorative fillings, dental caries, residual roots, and root canal fillings on orthopantomographs: Convenience and pitfalls. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, M.L.; Jacobs, R.; de Souza Leal, R.M.; Fontenele, R.C. AI-driven segmentation of the pulp cavity system in mandibular molars on CBCT images using convolutional neural networks. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Junior, A.O.; Fontenele, R.C.; Neves, F.S.; Ali, S.; Jacobs, R.; Tanomaru-Filho, M. A unique AI-based tool for automated segmentation of pulp cavity structures in maxillary premolars on CBCT. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.C.; Lucas-Oliveira, E.; Bonagamba, T.J.; Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M.; Tanomaru-Filho, M. Effect of voxel size of Micro-CT on the assessment of root canal preparation. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 25, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Root Canal Therapy Evaluation Based on Rule Embedded Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Automation and Applications (ICAA), Nanjing, China, 25–27 June 2021; pp. 749–754. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchahma, M.; Hammouda, S.B.; Kouki, S.; Alshemaili, M.; Samara, K. An automatic dental decay treatment prediction using a deep convolutional neural network on X-Ray images. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACS 16th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Latke, V.; Narawade, V. Enhancing Endodontic Precision: A Novel AI-Powered Hybrid Ensemble Approach for Refining Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhari, P. An Intelligent way of detecting dental diseases and recommendation of possible treatments. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, H.A.; Saad, F.H.; Ahmed, S.; Mohammed, N.; Farook, T.H.; Dudley, J. Experimental validation of computer-vision methods for the successful detection of endodontic treatment obturation and progression from noisy radiographs. Oral Radiol. 2023, 39, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, P.; Rajawat, A.S.; Goyal, S. Longevity Recommendation for Root Canal Treatment Using Machine Learning. Eng. Proc. 2024, 59, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Bennasar, C.; García, I.; Gonzalez-Cid, Y.; Pérez, F.; Jiménez, J. Second Opinion for Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment Prognosis Using Machine Learning Models. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lin, H.; Huang, X.; Gu, L. Machine learning models for prognosis prediction in endodontic microsurgery. J. Dent. 2022, 118, 103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkehabadi, H.; Khoshbin, E.; Ghasemi, N.; Mahavi, A.; Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Sadr, S. Deep learning for determining the difficulty of endodontic treatment: A pilot study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Versiani, M.; De-Deus, G.; Dummer, P. A new system for classifying root and root canal morphology. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, K.; Huang, H. Three-dimension model of root canal morphology of primary maxillary incisors by micro-computed tomography study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.G.; Anderegg, A.L.; Haberthür, D.; Khoma, O.Z.; Schumann, S.; Boemke, N.; Wierichs, R.J.; Hlushchuk, R. Internal morphology of 101 mandibular canines of a Swiss-German population by means of Micro-CT: An ex vivo study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.G.; Rempapi, T.; Schumann, S.; Campus, G.; Spagnuolo, G.; Armogida, N.G.; Waber, A.L. Micro-computed tomographic analysis of the morphology of maxillary lateral incisors. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.G.; Stiebritz, M.; Boemke, N.; Elsayed, I.; Paqué, F.; Wierichs, R.J.; Briseño-Marroquín, B. 3-dimensional analysis and literature review of the root canal morphology and physiological foramen geometry of 125 mandibular incisors by means of micro–computed tomography in a German population. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karobari, M.I.; Arshad, S.; Noorani, T.Y.; Ahmed, N.; Basheer, S.N.; Peeran, S.W.; Marya, A.; Marya, C.M.; Messina, P.; Scardina, G.A. Root and root canal configuration characterization using microcomputed tomography: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraiwa, T.; Ariji, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Kise, Y.; Nakata, K.; Katsumata, A.; Fujita, H.; Ariji, E. A deep-learning artificial intelligence system for assessment of root morphology of the mandibular first molar on panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatvani, J.; Horváth, A.; Michetti, J.; Basarab, A.; Kouamé, D.; Gyöngy, M. Deep learning-based super-resolution applied to dental computed tomography. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2018, 3, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfeir, R.; Michetti, J.; Chebaro, B.; Diemer, F.; Basarab, A.; Kouamé, D. Dental root canal segmentation from super-resolved 3D cone beam computed tomography data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), Atlanta, GA, USA, 21–28 October 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sfeir, R.; Chebaro, B.; Julien, C. Fast 3D Volume Super Resolution Using an Analytical Solution for l2-l2 Problems. Int. J. Image Graph. Signal Process. 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Long, Z.; Gao, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhang, L. Construction and evaluation of an AI-based CBCT resolution optimization technique for extracted teeth. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B. A lightweight convolutional neural network model with receptive field block for C-shaped root canal detection in mandibular second molars. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Gsaxner, C.; Pepe, A.; Schmalstieg, D.; Kleesiek, J.; Egger, J. Sparse convolutional neural network for high-resolution skull shape completion and shape super-resolution. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince Yusufoglu, S.; Saricam, E.; Ozdogan, M.S. Finite Element Analysis of Stress Distribution in Root canals when using a Variety of Post systems Instrumented with different Rotary systems. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, N.; Santhosh, L.; Panchajanya, S.; Srinivasan, A. Evaluation using finite element analysis of three root canal preparation tapers on stresses within the roots. IP Indian J. Conserv. Endod. 2022, 7, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafeez, M.M. Applications of finite element analysis in endodontics: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S1977–S1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özata, M.Y.; Adıgüzel, Ö.; Falakaloğlu, S. Evaluation of stress distribution in maxillary central incisor restored with different post materials: A three-dimensional finite element analysis based on micro-CT data. Int. Dent. Res. 2021, 11, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; VanHeel, B.; Zhang, L.; Lee, R.; Ye, Z.; Xu, H.; Fok, A.S. Experimental investigation and finite element analysis on the durability of root-filled teeth treated with multisonic irrigation. Dent. Mater. 2025, 41, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Wang, H.W.; Lin, P.H.; Lin, C.L. Evaluation of early resin luting cement damage induced by voids around a circular fiber post in a root canal treated premolar by integrating micro-CT, finite element analysis and fatigue testing. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Fan, W.; Mishra, S.; El-Atem, A.; Schuetz, M.A.; Xiao, Y. Tooth fracture risk analysis based on a new finite element dental structure models using micro-CT data. Comput. Biol. Med. 2012, 42, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Gao, J.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; He, Y. Evaluation algorithm of root canal shape based on steklov spectrum analysis. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2019, 2019, 4830914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamburoğlu, K.; Sönmez, G.; Koç, C.; Yılmaz, F.; Tunç, O.; Isayev, A. Access cavity preparation and localization of root canals using guides in 3D-printed teeth with calcified root canals: An in vitro CBCT study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinkovych-Levchuk, K.; Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Castelo-Baz, P.; Pecci-Lloret, M.R.; Oñate-Sánchez, R.E. Guided endodontics: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattas, M.H. The Role of 3D Printing in Endodontic Treatment Planning: A Comprehensive Review. Eur. J. Dent. 2024, 19, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, I.K.; Khor, M.M.Y.; Tan, B.L.; Wong, R.C.W.; Duggal, M.S.; Soh, S.H.; Lu, W.W. Tooth autotransplantation with 3D-printed replicas as part of interdisciplinary management of children and adolescents: Two case reports. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyaz, Y.; Ali, M.; Ullah, R.; Shaikh, M.S. Applications of 3D-printed teeth in dental education: A narrative review. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2024, 19, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, R.; Spintzyk, S.; Tian, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, T. Three-dimensional printed tooth model with root canal ledge: A novel educational tool for endodontic training. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reymus, M.; Liebermann, A.; Diegritz, C. Virtual reality: An effective tool for teaching root canal anatomy to undergraduate dental students—A preliminary study. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Gao, Q.; Wang, N.; Greene, N.; Song, T.; Dianat, O.; Azimi, E. Mixed reality guided root canal therapy. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Eecognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rud, J.; Andreasen, J.; Jensen, J.M. Radiographic criteria for the assessment of healing after endodontic surgery. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1972, 1, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, F.S.; Healey, H.J.; Gerstein, H.; Evanson, L. Canal configuration in the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar and its endodontic significance. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1969, 28, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, F. Endodontic Therapy, 3rd ed.; The C.V. Mosby Company: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Vertucci, F.; Seelig, A.; Gillis, R. Root canal morphology of the human maxillary second premolar. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1974, 38, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertucci, F.J. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 58, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briseño-Marroquín, B.; Paqué, F.; Maier, K.; Willershausen, B.; Wolf, T.G. Root canal morphology and configuration of 179 maxillary first molars by means of micro–computed tomography: An ex vivo study. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 2008–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.C.; Zhou, S.; Xu, X.; Loy, C.C. Basicvsr++: Improving video super-resolution with enhanced propagation and alignment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Denver CO, USA, 3–7 June 2022; pp. 5972–5981. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ellis, D.G.; Kodym, O.; Rauschenbach, L.; Rieß, C.; Sure, U.; Wrede, K.H.; Alvarez, C.M.; Wodzinski, M.; Daniol, M.; et al. Towards clinical applicability and computational efficiency in automatic cranial implant design: An overview of the autoimplant 2021 cranial implant design challenge. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 88, 102865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuessinger, M.A.; Schwarz, S.; Cornelius, C.P.; Metzger, M.C.; Ellis, E.; Probst, F.; Semper-Hogg, W.; Gass, M.; Schlager, S. Planning of skull reconstruction based on a statistical shape model combined with geometric morphometrics. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambellan, F.; Tack, A.; Ehlke, M.; Zachow, S. Automated segmentation of knee bone and cartilage combining statistical shape knowledge and convolutional neural networks: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 52, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.A.; Langenderfer, J.E.; Rullkoetter, P.J.; Laz, P.J. Development of subject-specific and statistical shape models of the knee using an efficient segmentation and mesh-morphing approach. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2010, 97, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, A.; Fripp, J.; Engstrom, C.; Schwarz, R.; Lauer, L.; Salvado, O.; Crozier, S. Automated detection, 3D segmentation and analysis of high resolution spine MR images using statistical shape models. Phys. Med. Biol. 2012, 57, 8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogenson, M.; Duff, J.M.; Luethi, M.; Levivier, M.; Meuli, R.; Baur, C.; Henein, S. A statistical shape model of the human second cervical vertebra. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2015, 10, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, F.; Raffa, G.M.; Gentile, G.; Agnese, V.; Bellavia, D.; Pilato, M.; Pasta, S. Statistical shape analysis of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm: Correlation between shape and biomechanical descriptors. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiputra, H.; Matsumoto, S.; Wagenseil, J.E.; Braverman, A.C.; Voeller, R.K.; Barocas, V.H. Statistical shape representation of the thoracic aorta: Accounting for major branches of the aortic arch. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 26, 1557–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordas, S.; Oubel, E.; Leta, R.; Carreras, F.; Frangi, A.F. A statistical shape model of the heart and its application to model-based segmentation. In Medical Imaging 2007: Physiology, Function, and Structure from Medical Images; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; Volume 6511, pp. 490–500. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, X.; Pereañez, M.; Hoogendoorn, C.; Swift, A.J.; Wild, J.M.; Frangi, A.F.; Lekadir, K. An algorithm for the segmentation of highly abnormal hearts using a generic statistical shape model. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 35, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Herskovits, E.H.; Davatzikos, C. An adaptive-focus statistical shape model for segmentation and shape modeling of 3-D brain structures. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2001, 20, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, P.; Wolleb, J.; Bieder, F.; Thieringer, F.M.; Cattin, P.C. Point cloud diffusion models for automatic implant generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 October 2023; pp. 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkühler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

| Terminology | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Root canal | The pulpal space within the root(s) |

| Canal orifice | The opening of a root canal |

| Apical foramen | The root tip opening where nerves, vessels enter the tooth |

| Root canal configuration | The shape, number, and branching of root canals |

| Single- or multi-rooted teeth | Teeth with a single or multiple roots (Molars typically have multiple roots, while incisors and canines have a single root. Note that a root can contain multiple canals, depending on the tooth type and canal branching.) |

| Coronal, middle apical | Parts of the tooth root from crown to root tip |

| Lateral (accessory) root canal | Canals branching from the main root canal |

| Isthmus | An irregular connection between two canals in a root |

| MB2 canal | The second canal within the MB root of maxillary/upper molars |

| Pulp stone | Calcified deposit found within the dental pulp |

| Defects | A broad term referring to any imperfections in root canal filling |

| Voids and Pores | Entrapped air inside the filling materials |

| Debris | Leftover tissue and bacteria after pulp removal |

| Gaps & Delamination | Separation of layers between sealer, dentin, gutta-percha |

| Modality | Resolution | Dimension | Feature | Radiation | Usage | Micro-Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | high | 2D | in vivo and non-destructive | low | clinical routine | Limited |

| CBCT | moderate | 3D | in vivo and non-destructive | moderate | clinical routine | Large voids or gaps, root apex |

| Microscopic | ultra-high | 2D | ex vivo and destructive | none | research | Surface morphology and material-dentin interaction |

| Micro-CT | high | 3D | ex vivo and non-destructive (While being ex vivo, micro-CT is considered ’non-destructive’, with respect to the imaged sample, i.e., tooth.) | very high | research | 3D evaluation of material distribution, voids, and gaps |

| PCE micro-CT | high | 3D | ex vivo and non-destructive | very high | research | Finer micro-structure details with varying contrasts |

| MRI | moderate | 3D | ex vivo and non-destructive | non-ionizing | research | Clear distinction of dental materials, e.g., dentin, sealer and gutta-percha |

| Paper | Modality | Method | Target | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deleat-Besson et al. [56] (2020) | CBCT | 2D U-Net | Crowns and Root canals | Match crowns with the respective root canals |

| Dumont et al. [57] (2020) | CBCT | 2D U-Net | Crowns and root canals | Match crowns with the respective root canals |

| Wang et al. [58] (2023) | CBCT | 3D PulpNet | Tooth and root canals | Jointly segment teeth and root canals |

| Duan et al. [59] (2021) | CBCT | 3D U-Net | Tooth and pulp cavity | Single and multi-rooted teeth |

| Zhang et al. [60] (2021) | CBCT | 3D U-Net | Root canals | Root canal area and contour |

| Li et al. [61] (2023) | CBCT | transformer | Tooth and root canals | Jointly segment teeth and root canals |

| Zhang et al. [62] (2022) | CBCT | cGAN | Caries, enamel, dentin, dental pulp, crown, root canal | Segment multiple tooth sub-structures |

| Harris et al. [63] (2023) | CBCT | dental anatomy- based heuristics | Tooth and pulp | Single and multi-rooted teeth |

| Tan et al. [64] (2024) | CBCT | Attention-based deep learning | Enamel, pulp and dentin | Robust against dental artifacts like metal and calcification |

| Lin et al. [6] (2021) | CBCT + Micro-CT | 2D U-Net | Tooth and pulp cavity | Train U-Net using manual labels from CBCT and threshold-based labels from micro-CT |

| Michetti et al. [28] (2017) | CBCT + Micro-CT | Thresholding | Root canals | Comparison of CBCT and Micro-CT segementation |

| Machado et al. [65] (2019) | CBCT + Micro-CT | Thresholding | Root canals | Comparison of CBCT and Micro-CT segmentation |

| Haberthür et al. [27] (2021) | Micro-CT | Otsu threshold and island removal | Root canals | Segment the root canal and analyze the morphology |

| Ari et al. [66], Gardiyanoğlu et al. [67] (2022, 2023) | X-ray | 2D U-Net | Various dental structures (Caries, implants, lesion, crown, pulp, root canal filling) | Jointly segment various structures of treated teeth |

| Slim et al. [68], Santos-Junior et al. [69] (2024, 2025) | CBCT | 3D U-Net | Pulp cavity | Pulp cavity of molar and premolar teeth |

| Paper | Modality | Method | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinto et al. [70] (2023) | Micro-CT | Statistical analysis (Student’s t-test and ANOVA tests) | Effect of micro-CT voxel size on the evaluation of root canal preparation |

| Lamira et al. [4] (2022) | Micro-CT and CBCT | Statistical analysis (kappa coefficient, variance, Tukey test) | Comparison of CBCT- and micro-CT-based RCT quality evaluation |

| Zhou and Zhang [71] (2021) | X-ray | ResNet | Generate a quantitative score based on treated images to reflect treatment quality |

| Bouchahma et al. [72] (2019) | X-ray | CNN-based image classification | Predict treatment options for dental decay |

| Latke and Narawade [73] (2023) | X-ray | SVM, KNN | Predict treatment options for dental decay |

| Choudhari [74] (2022) | - | - | Detect dental diseases and recommend treatment |

| Hasan et al. [75] (2023) | X-ray | YOLO network | Predict RCT outcome |

| Choudhari et al. [76] (2024) | X-ray | logistic regression, Bayes, SVM | Predict RCT failure types and longevity |

| Bennasar et al. [77] (2023) | X-ray | RF, KNN | Predict prognosis—success or failure, using pre-operative features |

| Qu et al. [78] (2022) | CBCT | GBM, RF | Predict prognosis—outcome one year after treatment |

| Karkehabadi et al. [79] (2024) | X-ray | VGG, ResNet and Inception | Assess RCT difficulty |

| Liu et al. [42], Peng et al. [41] (2022, 2024) | X-ray | U-Net, ResNet | Quantitative evaluation of RCT quality based on segmented canal and filling area |

| Shetty et al. [43] (2021) | CBCT | OsiriX MD and 3D Slicer and Materialize MiniMagics | Pulp volume estimation before and after RCT |

| Paper | Modality | Method | Target | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haberthür et al. [27] (2021) | Micro-CT | Briseño classification | Root canals | RCC Classification using four slices |

| Ahmed et al. [80] (2017) | Micro-CT | - | Root canals | A new RCC scheme |

| Lyu et al. [81] (2024) | Micro-CT | Morphological measurement | Incisor root canals | Root canal measurement, e.g., length, volume, surface area |

| Wolf et al. [82] (2021) | Micro-CT | 3D imaging software | Canine root canal | Root canal classification and measurement of the extracted teeth of a Swiss-German population |

| Wolf et al. [83] (2024) | Micro-CT | 3D imaging software | Incisor root canal | Root canal classification and measurement of the extracted teeth of a Swiss-German population |

| Wolf et al. [84] (2020) | Micro-CT | 3D imaging software | Incisor root canals | Root canal classification and measurement of the extracted teeth of a German population |

| Wu et al. [5] (2024) | Micro-CT and X-ray | VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet | Second, molar root canals | Classification of second molar morphology types based on 2D X-rays, using 3D micro-CT as ground truth |

| Karobari et al. [85] (2022) | Micro-CT | - | Anterior and third molar toot canals | A systematic review of root canal morphology classification |

| Hiraiwa et al. [86] (2019) | CBCT and X-ray | AlexNet and GoogleNet | First, molar distal root canals | Classification of root canal morphology based on radiographs using CBCT as ground truth |

| Hatvani et al. [87] (2018) | Micro-CT and CBCT | 2D U-Net | Incisor, canine, premolar, and molar root canals | Super-resolution: CBCT → Micro CT |

| Sfeir et al. [88], Sfeir et al. [89] (2017, 2020) | CBCT | Linear model | First, premolar, first molar, second molar, incisor | CBCT Super-resolution |

| Ji et al. [90] (2024) | CBCT | Basicvsr++ | First, molar | Super-resolution: CBCT → Micro CT |

| Zhang et al. [91] (2022) | X-ray | - | Second, molar root canals | - |

| Task | Methods and Description |

|---|---|

| Image Classification/Prognosis Prediction | ResNet, VGG, Inception, CNNs, SVM, KNN, Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Logistic Regression, Bayes Used to classify images, predict treatment options, or assess prognosis. |

| Segmentation of anatomical structures | U-Net (2D/3D), nnU-Net Automatically identifies and extracts root canal or filling regions from images. |

| Object Detection | YOLO network Detects regions of interest or pathological features on X-ray images. |

| Visualization/3D Reconstruction | 3D Slicer, OsiriX MD, Materialise MiniMagics Used for visualizing and measuring root canal morphology and pulp volume. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Bitter, K.; Nguyen, A.D.; Shemesh, H.; Zaslansky, P.; Zachow, S. Computational Insights into Root Canal Treatment: A Survey of Selected Methods in Imaging, Segmentation, Morphological Analysis, and Clinical Management. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120579

Li J, Bitter K, Nguyen AD, Shemesh H, Zaslansky P, Zachow S. Computational Insights into Root Canal Treatment: A Survey of Selected Methods in Imaging, Segmentation, Morphological Analysis, and Clinical Management. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120579

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jianning, Kerstin Bitter, Anh Duc Nguyen, Hagay Shemesh, Paul Zaslansky, and Stefan Zachow. 2025. "Computational Insights into Root Canal Treatment: A Survey of Selected Methods in Imaging, Segmentation, Morphological Analysis, and Clinical Management" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120579

APA StyleLi, J., Bitter, K., Nguyen, A. D., Shemesh, H., Zaslansky, P., & Zachow, S. (2025). Computational Insights into Root Canal Treatment: A Survey of Selected Methods in Imaging, Segmentation, Morphological Analysis, and Clinical Management. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120579