Effects of miR-128-3p on Renal Inflammation in a Rat Periodontitis Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal and Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

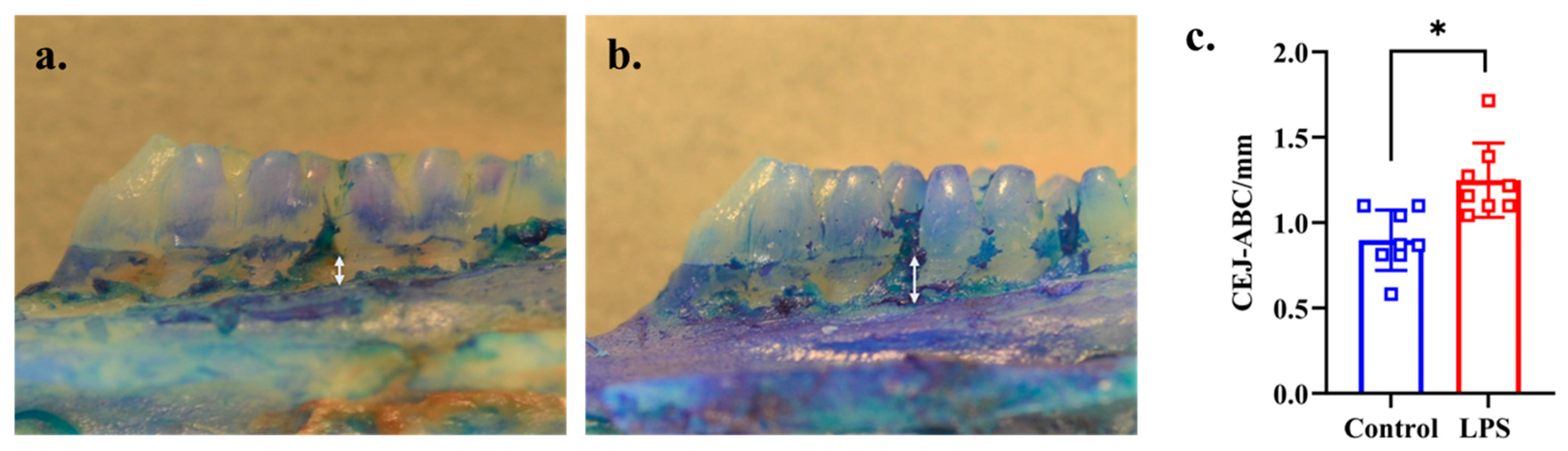

2.3. Measurement of Alveolar Bone Loss

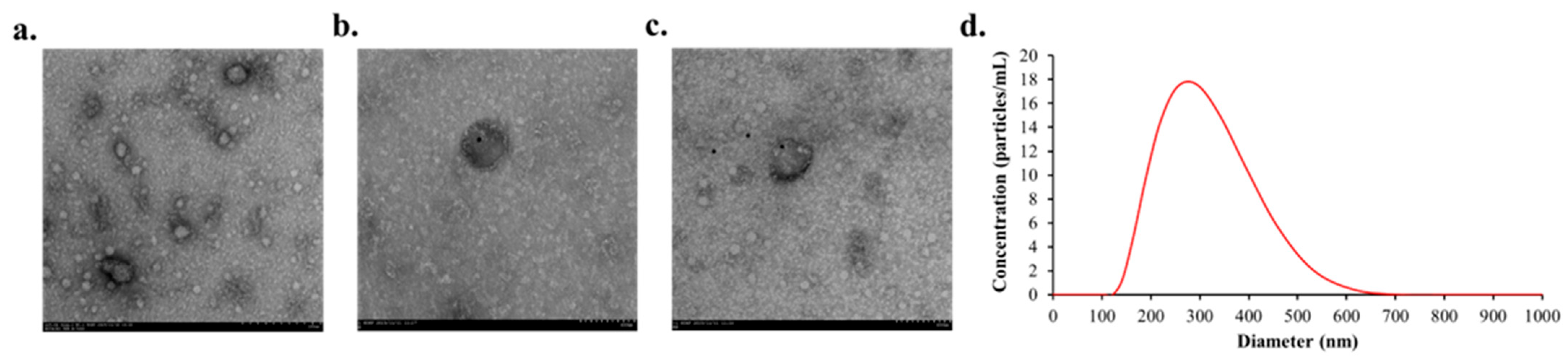

2.4. Immunogold Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.5. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

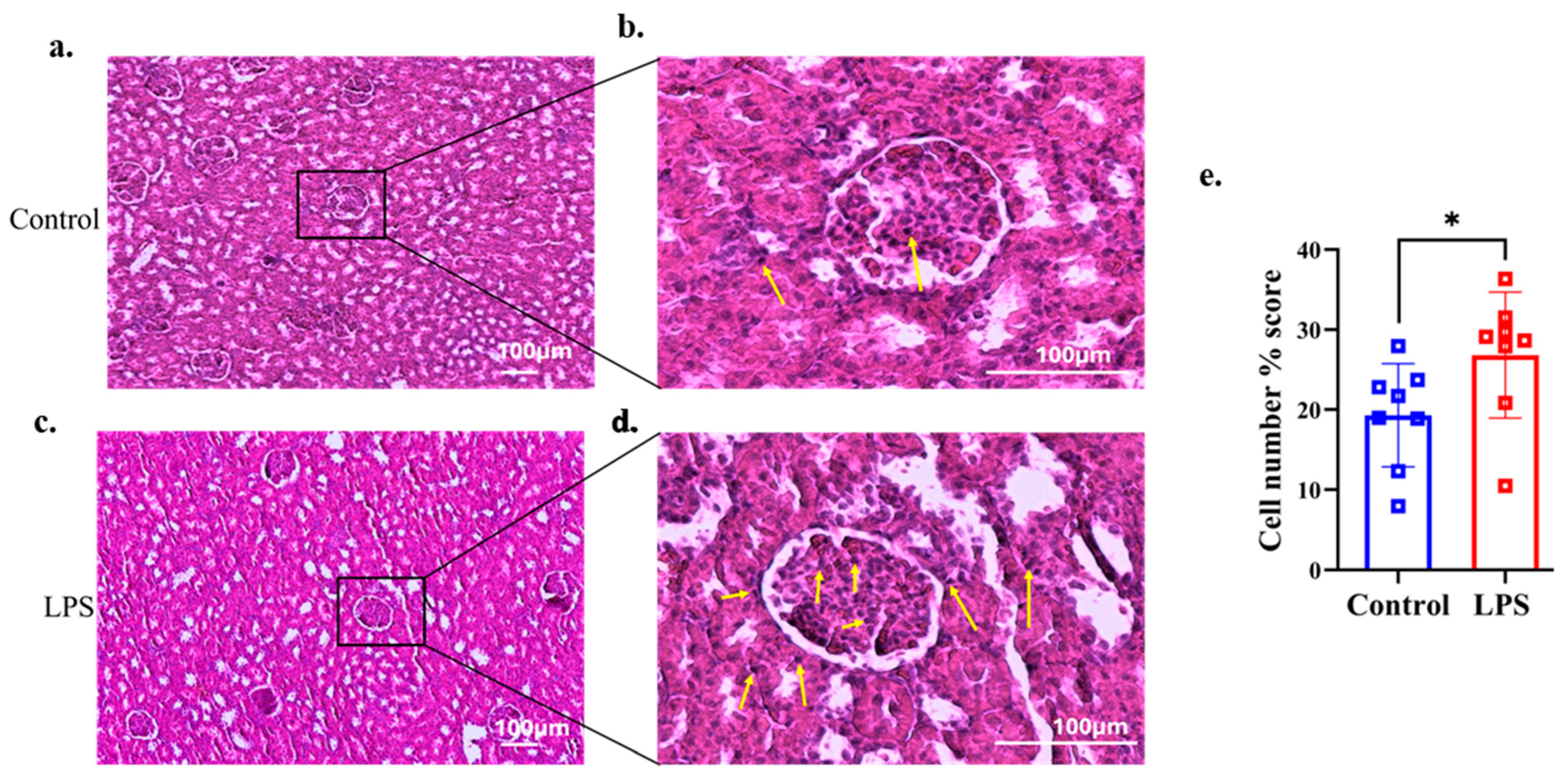

2.6. Kidney Histology

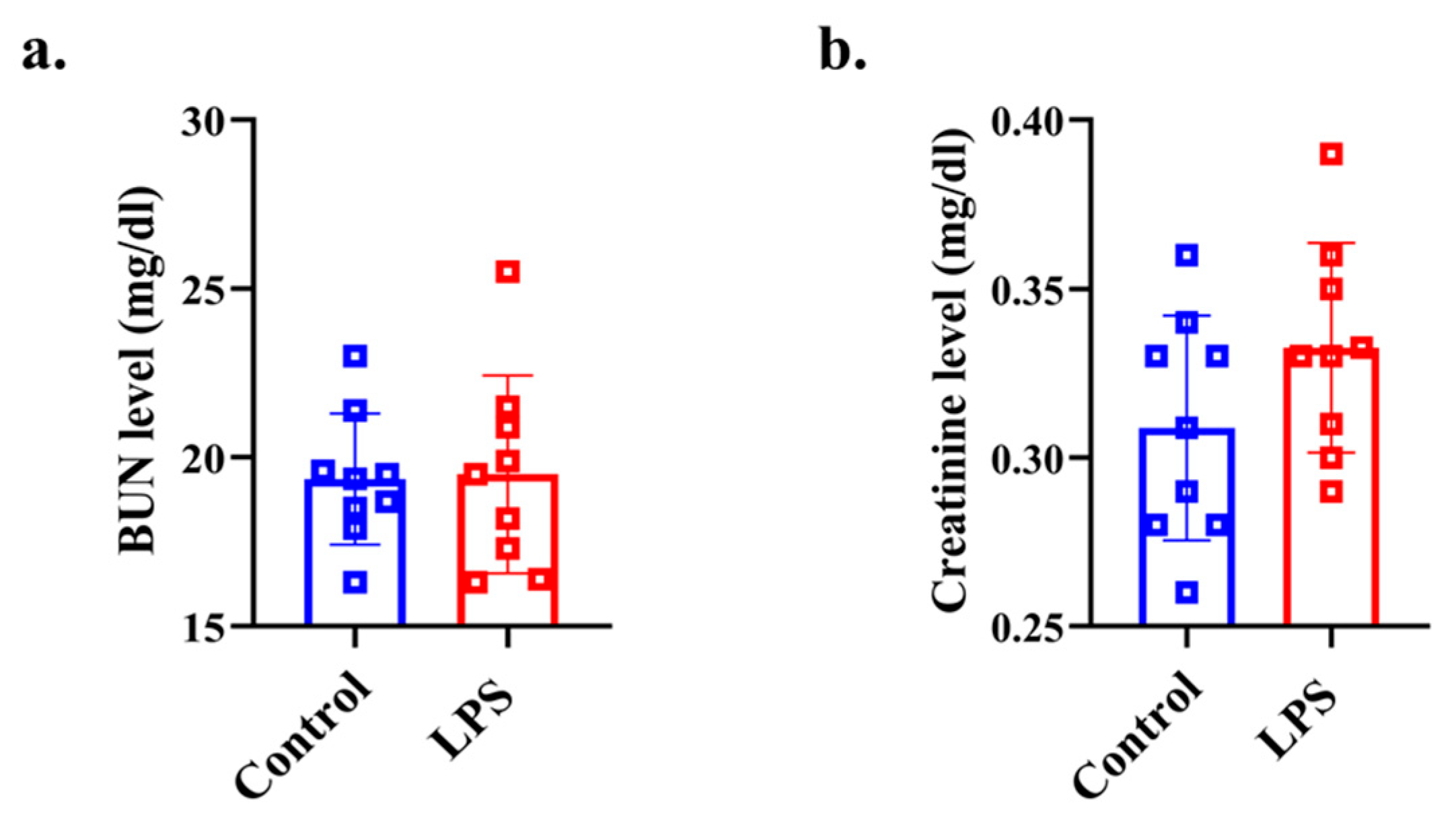

2.7. Plasma Biochemistry Analysis for Assessing Renal Function

2.8. Detection of Plasma LPS

2.9. Total RNA Extraction

2.10. The Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) of MiR-128-3p

2.11. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.12. Primer Design and mRNA Quantification

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight

3.2. Alveolar Bone Loss

3.3. Characteristics of Plasma EVs

3.4. Histological Findings of Renal Tissue

3.5. Plasma Renal Function Analysis

3.6. LPS Level of EU in Blood Plasma

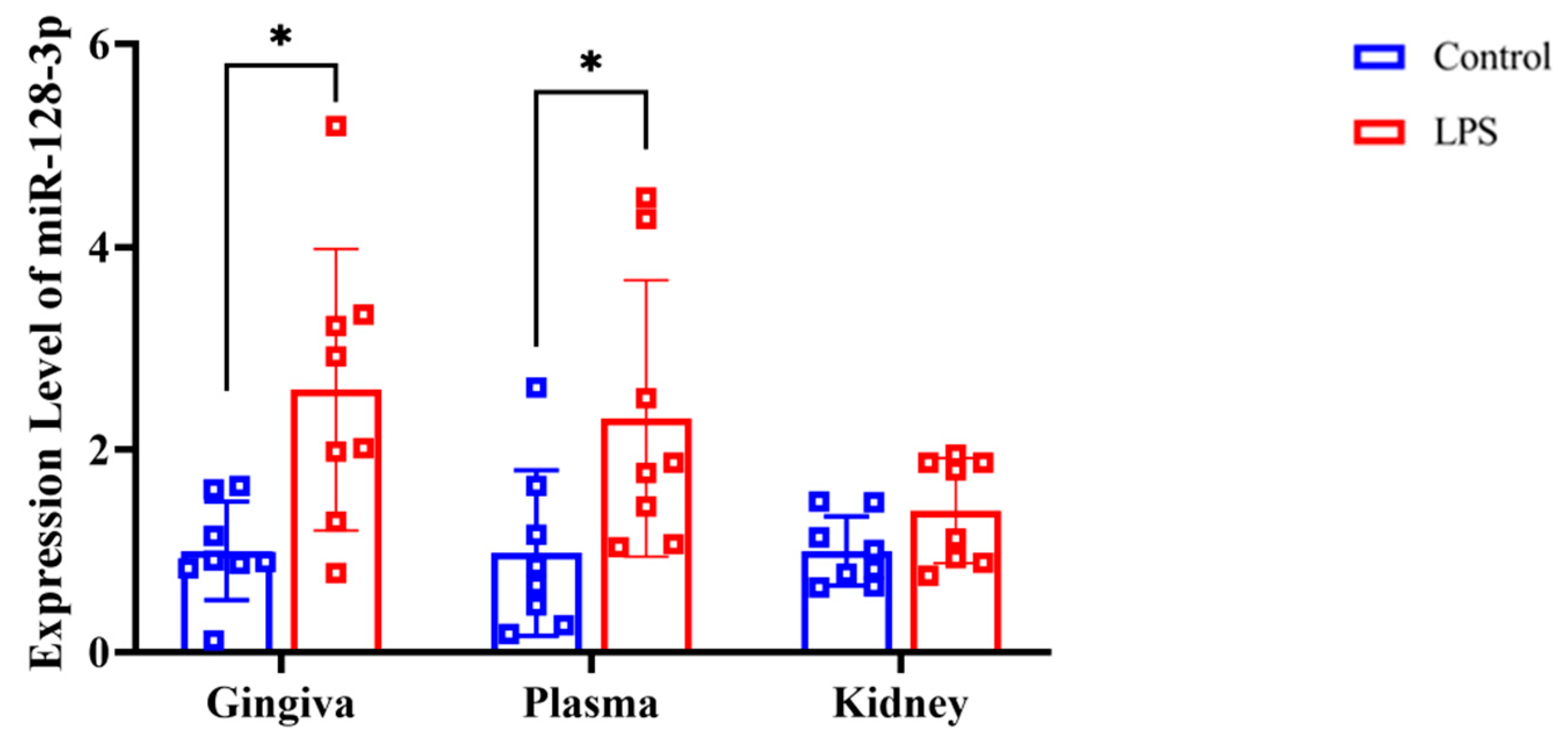

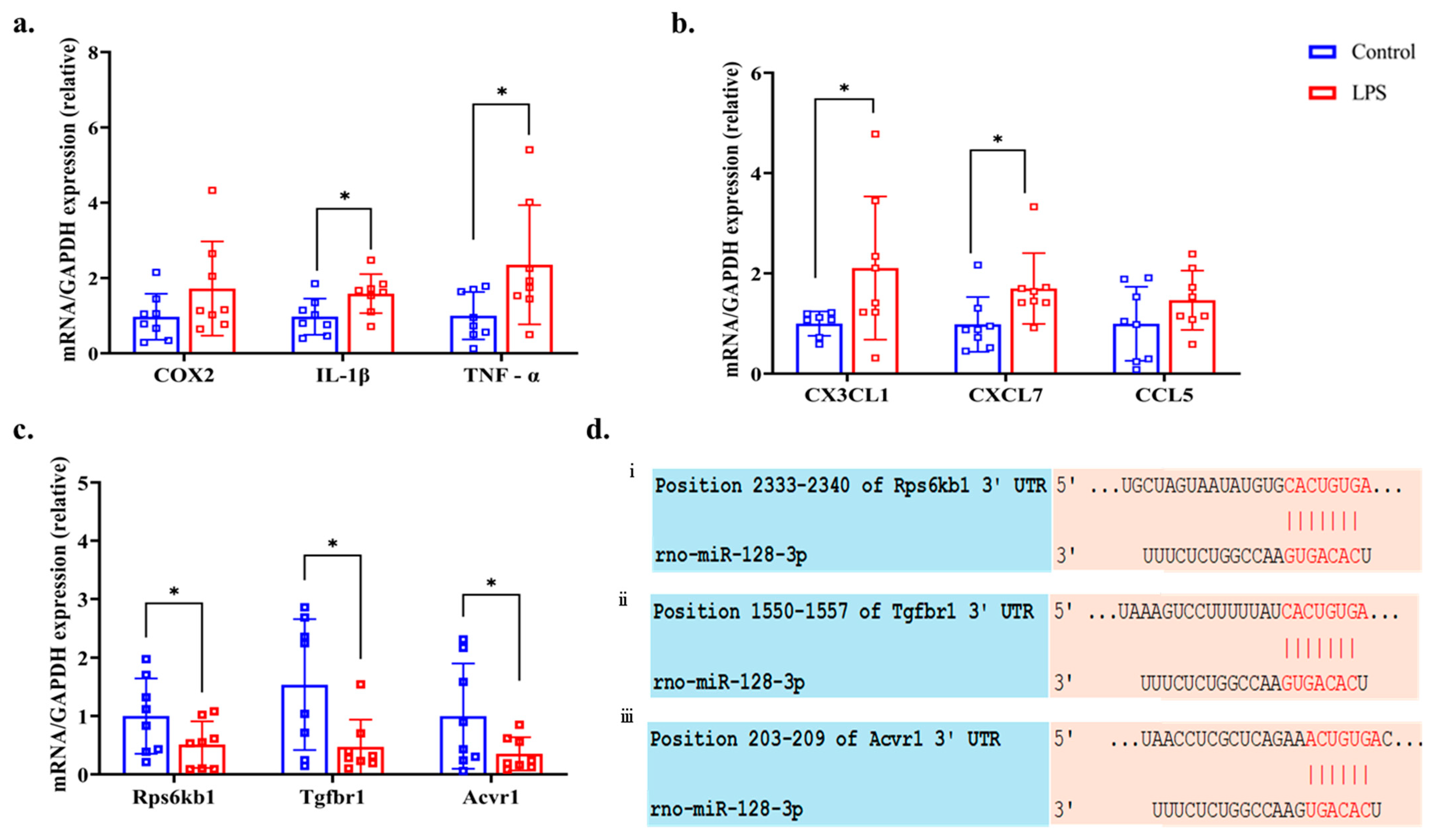

3.7. RT-qPCR of MiR-128-3p and Associated Genes

3.8. Bioinformatics and RT-qPCR of Predicting Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| SOCS-1 | suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharides |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| IL | interleukin |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| RANTES | regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted |

| OSM | oncostatin M |

| ARRIVE | Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments |

| CEJ | cementoenamel junction |

| ABC | alveolar bone crest |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| EU | endotoxin units |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| NTA | nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| RT-qPCR | reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| UNG | uracil-DNA N-glycosylase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Acvr1 | activin A receptor type 1 |

| Rps6kb1 | ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 |

| Tgfbr1 | transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| CX3CL1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

| CXCL7 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 7 |

| CCL5 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| SD | standard deviation |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| S6K1 | S6 kinase 1 |

References

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.; Fanelli, V.; Merlotti, G.; Costamagna, A.; Deregibus, M.C.; Marengo, M.; Balzani, E.; Brazzi, L.; Camussi, G.; Cantaluppi, V. Dual Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Sepsis-Associated Kidney and Lung Injury. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.; Bushati, N.; Jan, C.H.; Kheradpour, P.; Hodges, E.; Brennecke, J.; Bartel, D.P.; Cohen, S.M.; Kellis, M. A Single Hox Locus in Drosophila Produces Functional microRNAs from Opposite DNA Strands. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova, J.; Turchinovich, A.; Shkurnikov, M.; Tonevitsky, A. Extracellular miRNAs and Cell–Cell Communication: Problems and Prospects. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomou, T.; Mori, M.A.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Konishi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Wolfrum, C.; Rao, T.N.; Winnay, J.N.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Grinspoon, S.K.; et al. Adipose-Derived Circulating miRNAs Regulate Gene Expression in Other Tissues. Nature 2017, 542, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakinowska, E.; Kiełbowski, K.; Pawlik, A. The Role of MicroRNA in the Pathogenesis of Acute Kidney Injury. Cells 2024, 13, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.L.; Feng, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.L.; Zhong, X.; Wu, W.J.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.F.; Tang, T.T.; et al. Exosomal miRNA-19b-3p of Tubular Epithelial Cells Promotes M1 Macrophage Activation in Kidney Injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Tian, Z. miR-128-3p Inhibits NRP1 Expression and Promotes Inflammatory Response to Acute Kidney Injury in Sepsis. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, C.; Bellomo, R.; Kellum, J.A. Acute Kidney Injury. Lancet 2019, 394, 1949–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Edelstein, C.L. Mediators of Inflammation in Acute Kidney Injury. Mediat. Inflamm. 2009, 2009, 137072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonventre, J.V.; Zuk, A. Ischemic Acute Renal Failure: An Inflammatory Disease? Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slots, J. Periodontitis: Facts, Fallacies and the Future. Periodontol 2000 2017, 75, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Sun, J.; Ji, Z.; Hu, J.; Jiang, Q. Gingipain and Oncostatin M Synergistically Disrupt Kidney Tight Junctions in Periodontitis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury. J. Periodontol. 2024, 95, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Tang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Yin, L.; Peng, J. MicroRNA-128-3p Aggravates Doxorubicin-Induced Liver Injury by Promoting Oxidative Stress via Targeting Sirtuin-1. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 146, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Gao, Q.; He, Y.; Deng, Q.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Shang, T.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, J.; et al. MiR-128-3p Mediates MRP2 Internalization in Estrogen-Induced Cholestasis through Targeting PDZK1. Acta Materia. Medica 2025, 4, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dagnæs-Hansen, F.; Løvschall, H.; Song, W.; Nielsen, G.K.; Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Kjems, J.; Gao, S. Macrophage-Mediated Nanoparticle Delivery to the Periodontal Lesions in Established Murine Model via Pg-LPS Induction. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 44, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Peng, C. Automated Quantification and Analysis of Cell Counting Procedures Using ImageJ Plugins. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 54719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Xu, S. Selenomethionine Alleviates LPS-Induced Chicken Myocardial Inflammation by Regulating the miR-128-3p-P38 MAPK Axis and Oxidative Stress. Metallomics 2020, 12, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Meng, X.; Zhao, R.; Ou, L.; Li, B.Z.; Xing, T. Periodontitis Exacerbates and Promotes the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease Through Oral Flora, Cytokines, and Oxidative Stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamasundar, S.; Ong, C.; Yung, L.L.; Dheen, S.T.; Bay, B.H. miR-128 Regulates Genes Associated with Inflammation and Fibrosis of Rat Kidney Cells In Vitro. Anat. Rec. 2018, 301, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leira, Y.; Iglesias-Rey, R.; Gómez-Lado, N.; Aguiar, P.; Sobrino, T.; D’Aiuto, F.; Castillo, J.; Blanco, J.; Campos, F. Periodontitis and vascular inflammatory biomarkers: An experimental in vivo study in rats. Odontology 2020, 108, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.A.; Ludwig, R.G.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Brandão, B.B.; Kahn, C.R. Extracellular miRNAs: From Biomarkers to Mediators of Physiology and Disease. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, J.; Ying, P.; Situ, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhu, J. Upregulation of NF-κB by USP24 Aggravates Ferroptosis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 210, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.S.; Park, M.H.; Song, Y.R.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.I.; Chung, J. Elevated MicroRNA-128 in Periodontitis Mitigates Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Response via P38 Signaling Pathway in Macrophages. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, e173–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H.J. Of Inflammasomes and Alarmins: IL-1β and IL-1α in Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2564–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzer, U.; Steinmetz, O.M.; Stahl, R.A.K.; Wolf, G. Kidney Diseases and Chemokines. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockwell, P.; Chakravorty, S.J.; Girdlestone, J.; Savage, C.O.S. Fractalkine Expression in Human Renal Inflammation. J. Pathol. 2002, 196, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.E.; Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Ye, R.D.; Harrison, J.K.; Bacon, K.B.; Zerwes, H.-G.; Feng, L. NF-κB-Dependent Fractalkine Induction in Rat Aortic Endothelial Cells Stimulated by IL-1β, TNF-α, and LPS. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 67, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanki, T.; Imai, T.; Kawai, S. Fractalkine/CX3CL1 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2017, 27, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, E.; Kolesar, L.; Brabcova, E.; Petrickova, K.; Petricek, M.; Jaresova, M.; Slavcev, A.; Striz, I. CXC and CC Chemokines Induced in Human Renal Epithelial Cells by Inflammatory Cytokines. APMIS 2009, 117, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Y.; Liu, X.S.; Huang, X.R.; Yu, X.Q.; Lan, H.Y. Diverse Role of TGF-β in Kidney Disease. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.E.; Ding, Y.; Kim, S.I. TGF-β Signaling via TAK1 Pathway: Role in Kidney Fibrosis. Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallage, S.; Irvine, E.E.; Barragan Avila, J.E.; Reen, V.; Pedroni, S.M.A.; Duran, I.; Ranvir, V.; Khadayate, S.; Pombo, J.; Brookes, S.; et al. Ribosomal S6 Kinase 1 Regulates Inflammaging via the Senescence Secretome. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 1544–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Baik, K.H.; Baek, K.H.; Chah, K.H.; Kim, K.A.; Moon, G.; Jung, E.; Kim, S.T.; Shim, J.H.; Greenblatt, M.B.; et al. S6K1 Negatively Regulates TAK1 Activity in the Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilthorpe, M.S.; Zamzuri, A.T.; Griffiths, G.S.; Maddick, I.H.; Eaton, K.A.; Johnson, N.W. Unification of the “Burst” and “Linear” Theories of Periodontal Disease Progression: A Multilevel Manifestation of the Same Phenomenon. J. Dent. Res. 2003, 82, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Yang, X.; Ye, N.; Li, S.; Han, Q.; Huang, J.; Wu, B. Gene in the regulation of periodontitis and its molecular mechanism. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 1961–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baima, G.; Arce, M.; Romandini, M.; Van Dyke, T. Inflammatory and Immunological Basis of Periodontal Diseases. J. Periodontol. Res. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, S.; Li, L.; Bruchfeld, A.; Stevens, K.I.; Moran, S.M.; Floege, J.; Caravaca-Fontán, F.; Mirioglu, S.; Teng, O.Y.K.; Frangou, E.; et al. Sex dimorphism in kidney health and disease: Mechanistic insights and clinical implication. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Genes | Annealing Temp (°C) | Length (bp) | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CX3CL1 | 67 | 150 | CCCATCCTCATACCCACCTTC | CCACCTGCTCTGTCTGTCTC |

| CXCL7 | 67 | 150 | CCCCTATTCTTTGTCCTGCTCTT | GGCACACTTCCTTTCCATTCTTC |

| CCL5 | 66 | 121 | GCTTTGCCTACCTCTCCCTC | GCACACACTTGGCGGTTC |

| COX2 | 66 | 131 | GGAGGAGAAGTGGGGTTTAGG | TTGATGGTGGCTGTCTTGGT |

| TNF-α | 68 | 133 | GGCGTGTTCATCCGTTCTCT | CCCAGAGCCACAATTCCCTT |

| IL-1β | 67 | 145 | TGTTTCCCTCCCTGCCTCT | TCATCCCATACACACGGACAAC |

| RPS6KB1 | 67 | 140 | GTGGATTGGTGGAGTCTGGG | GCTTCTTGTGTGAGGTAGGGAG |

| TGFBR1 | 68 | 150 | CTGCTTCTCATCGTGTTGGTG | AACTTTGTCTGTGGTCTCGGT |

| ACVR1 | 67 | 146 | AAGGGCTCATCACCACCAAC | CTTCCCGACACACTCCAACA |

| GAPDH | 68 | 100 | ACAAGATGGTGAAGGTCGGT | TCGTGGTTCACACCCATCAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nurhamim, M.; Zhang, Y.; Nakahara, M.; Fukuhara, D.; Nagashima, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Morita, M.; Ekuni, D. Effects of miR-128-3p on Renal Inflammation in a Rat Periodontitis Model. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120577

Nurhamim M, Zhang Y, Nakahara M, Fukuhara D, Nagashima Y, Maruyama T, Morita M, Ekuni D. Effects of miR-128-3p on Renal Inflammation in a Rat Periodontitis Model. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120577

Chicago/Turabian StyleNurhamim, Mohammad, Yixuan Zhang, Momoko Nakahara, Daiki Fukuhara, Yosei Nagashima, Takayuki Maruyama, Manabu Morita, and Daisuke Ekuni. 2025. "Effects of miR-128-3p on Renal Inflammation in a Rat Periodontitis Model" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120577

APA StyleNurhamim, M., Zhang, Y., Nakahara, M., Fukuhara, D., Nagashima, Y., Maruyama, T., Morita, M., & Ekuni, D. (2025). Effects of miR-128-3p on Renal Inflammation in a Rat Periodontitis Model. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120577