Computer-Guided Intraosseous Anesthesia as a Primary Anesthetic Technique in Oral Surgery and Dental Implantology—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistics

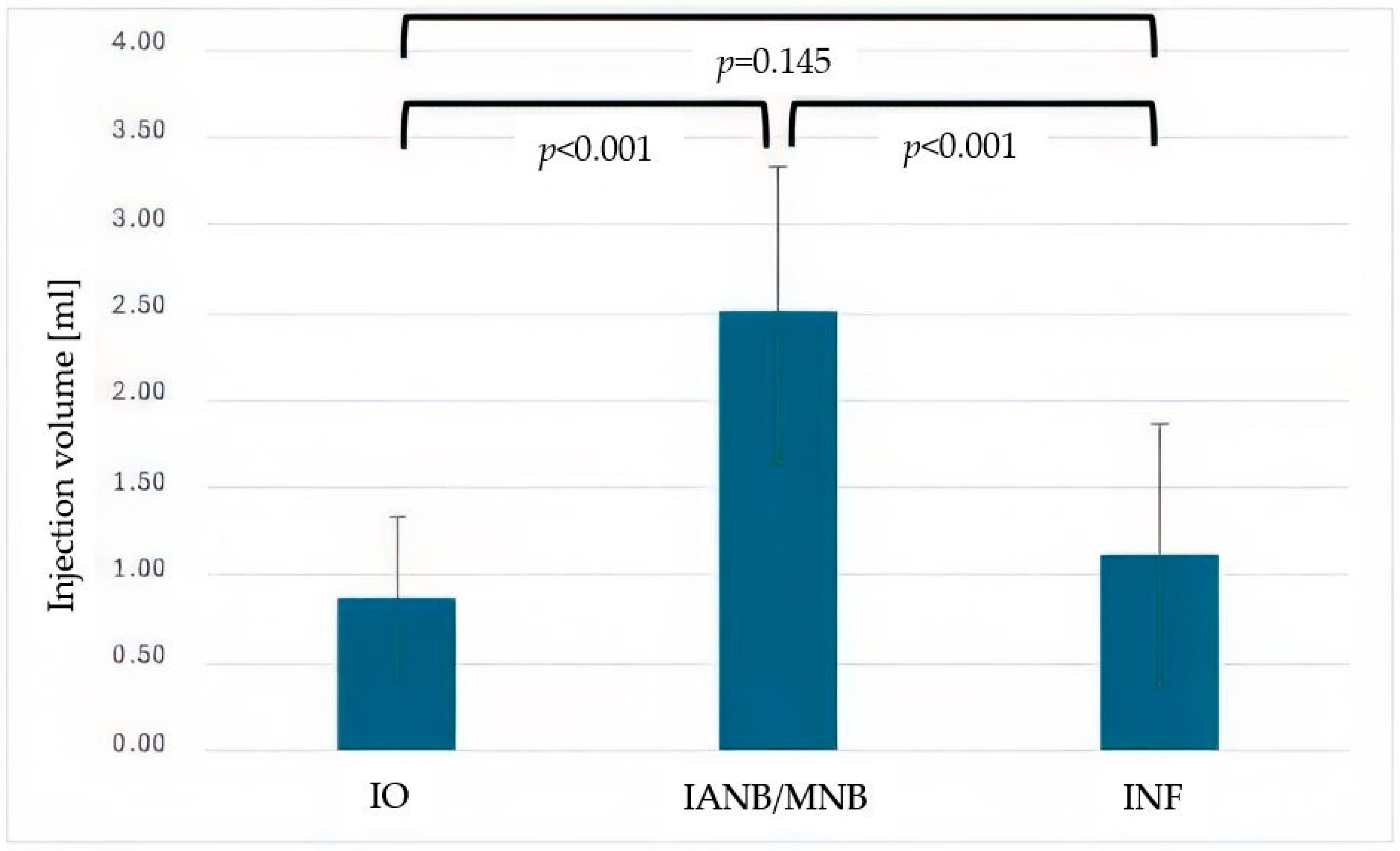

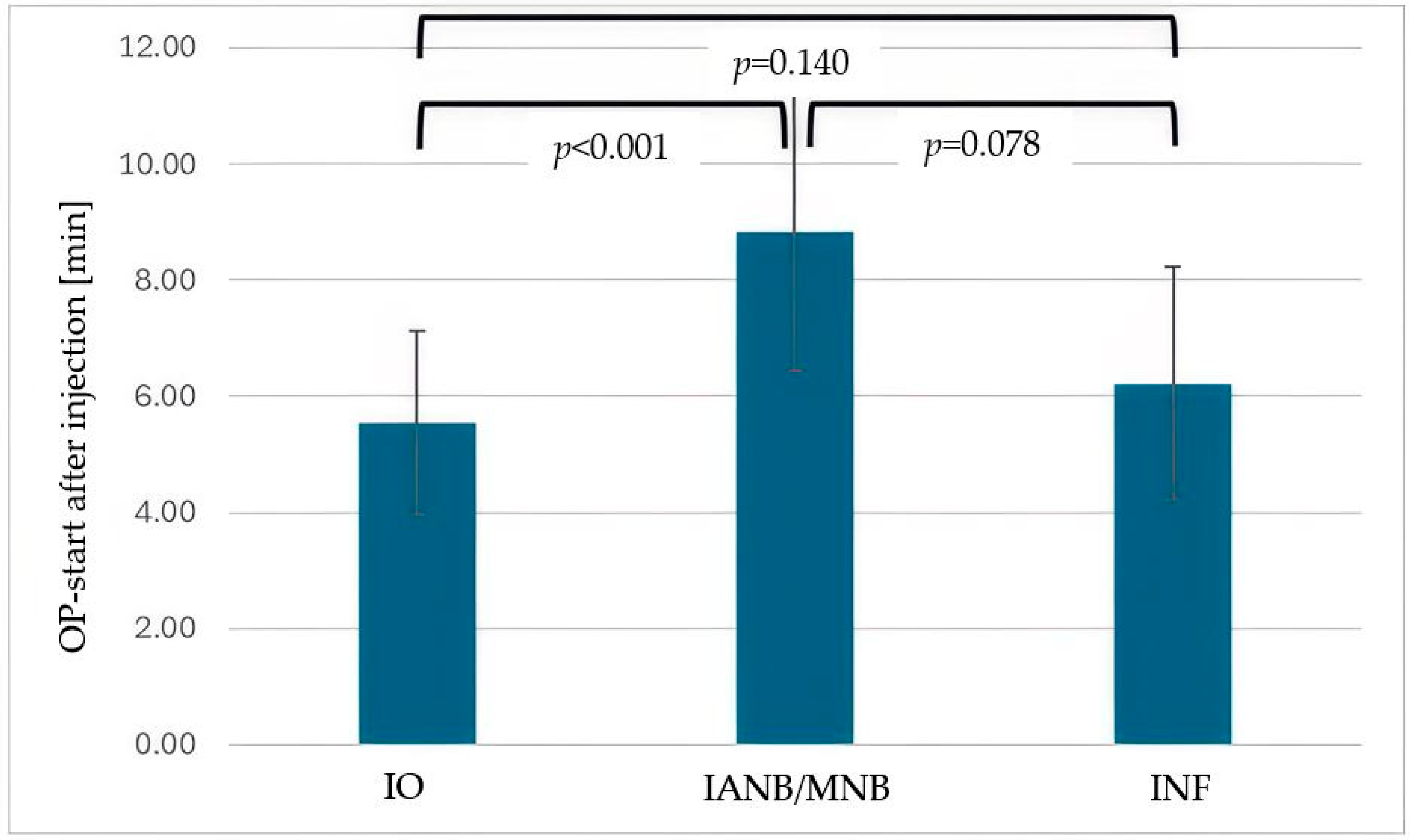

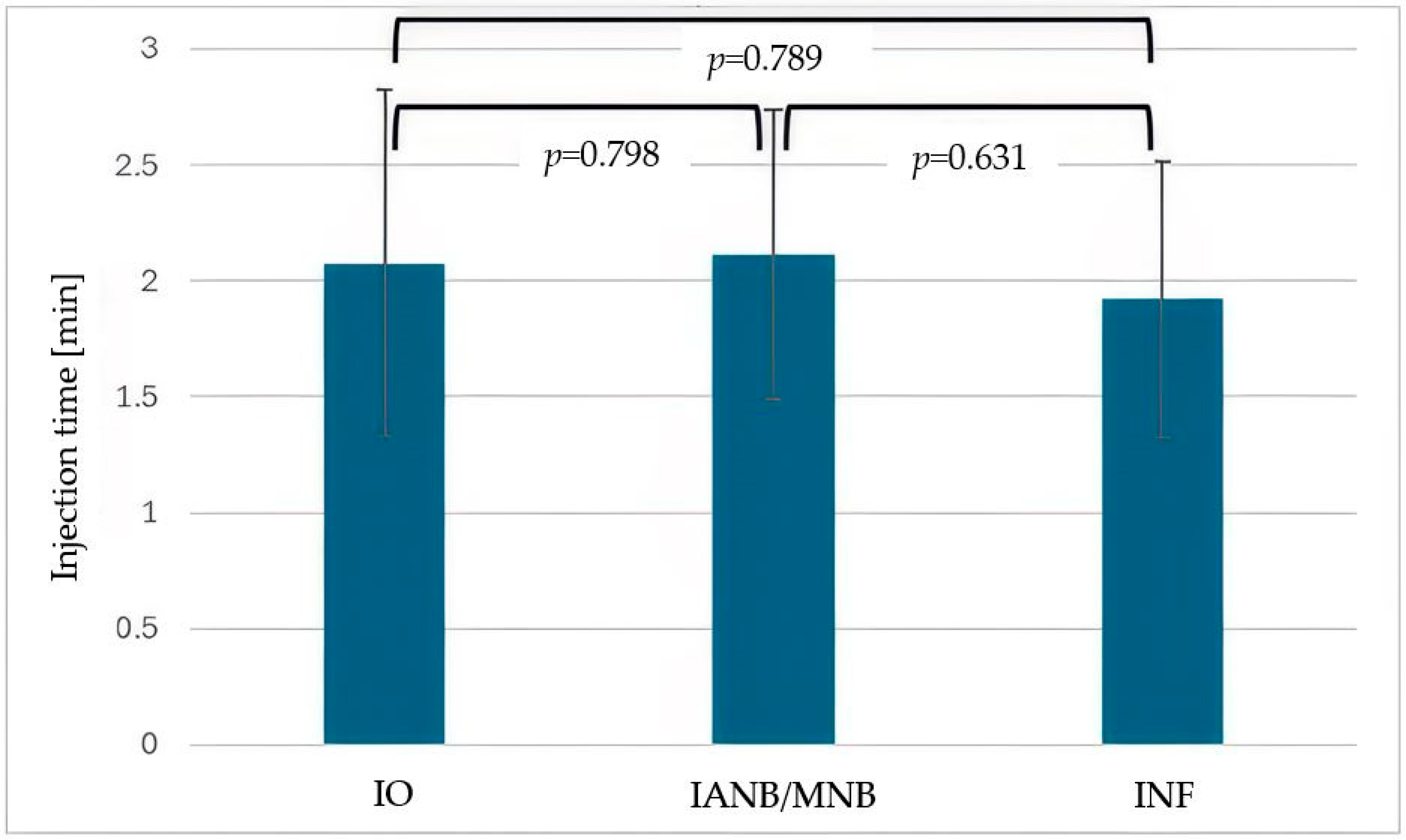

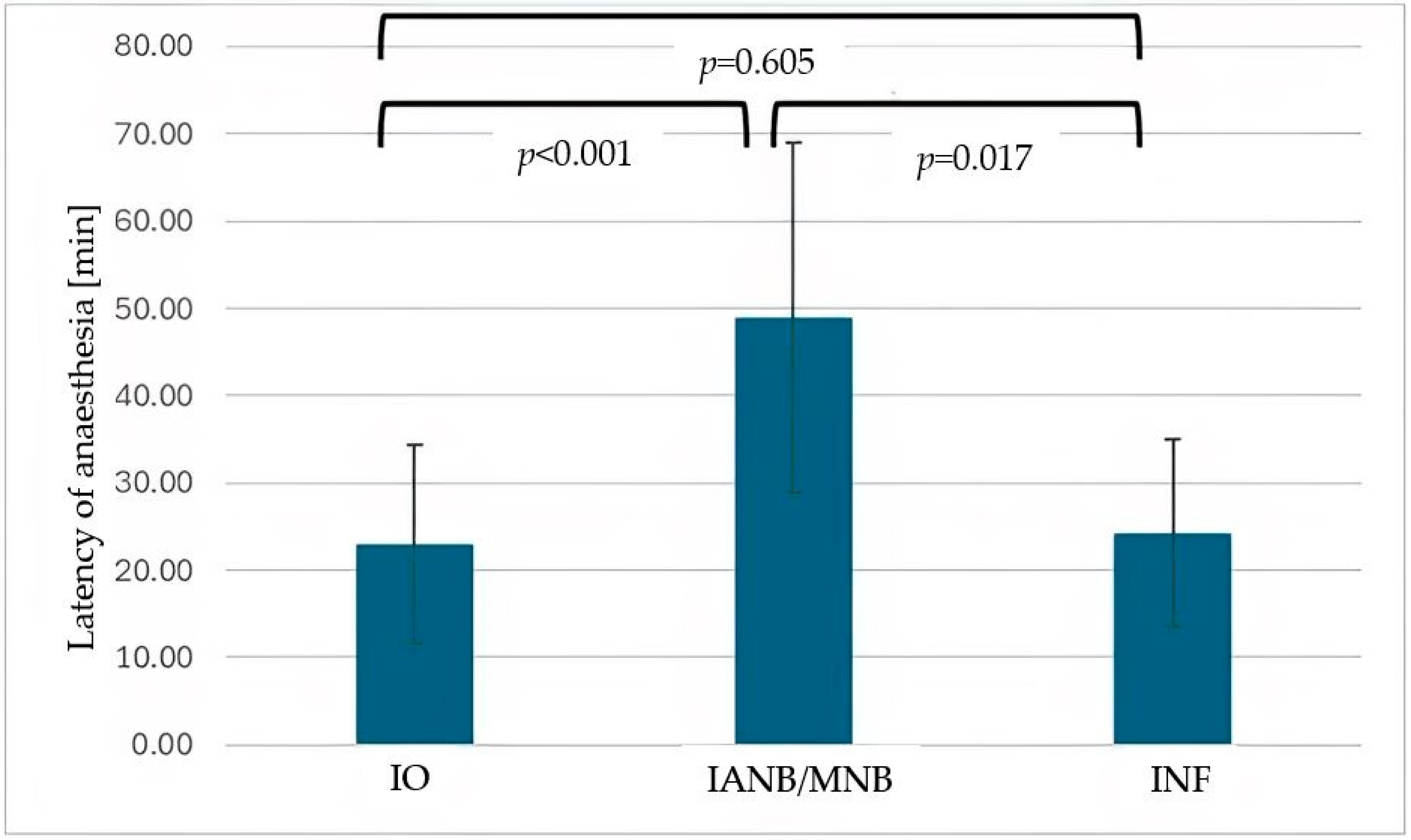

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bpm | beats per minute |

| IANB | inferior alveolar nerve block |

| INF | infiltration anesthesia |

| IO | computer-guided intraosseous anesthesia |

| RR dia | diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| RR sys | systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| StD | standard deviation |

References

- Akhtar, N.; Brizuela, M.; Stenhouse, P.D. Local Anesthetic Drugs Used in Dentistry [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK610935/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bartholomew, O.; Hogden, C.; Randall, C.L.; Qian, F.; Bowers, R. Challenges in achieving profound local anesthesia: Insights from a patient survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2025, 156, 530–537.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, R.H.; Zeitoun, S.I.; El-Habashy, L.M. Computer-controlled intraligamentary local anesthesia in extraction of mandibular primary molars: Randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Yang, H.J. Alternative techniques for failure of conventional inferior alveolar nerve block. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 19, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilius, M.; Mueller, C.; Nilius, M.H.; Haim, D.; Leonhardt, H.; Lauer, G. Intraosseous anesthesia in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: Impact of bone thickness on perception and duration of pain. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.M.; Badovinac, R.; Shaefer, J. Teaching alternatives to the standard inferior alveolar nerve block in dental education: Outcomes in clinical practice. J. Dent. Educ. 2007, 71, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, C.-Y.; Lee, S.J. An evaluation of buccal infiltrations and inferior alveolar nerve blocks in pulpal anesthesia for mandibular first molars. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaa, M.D.; Whitworth, J.M.; Meechan, J.G. A prospective randomized trial of different supplementary local anesthetic techniques after failure of inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with irreversible pulpitis in mandibular teeth. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakoui, S.; Ghodrati, M.; Ghasemi, N.; Pourlak, T.; Abdollahi, A.A. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine/epinephrine plus mannitol in comparison with articaine/epinephrine anesthesia for inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.; Jacobsen, P.L. Reasons for local anesthesia failures. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1992, 123, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, W.C. How to treat a difficult-to-anesthetize patient: Twelve alternatives to the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block. Todays FDA 2010, 22, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, V.; Singla, M.; Kabi, D. Comparative evaluation of anesthetic efficacy of Gow-Gates mandibular conduction anesthesia, Vazirani-Akinosi technique, buccal-plus-lingual infiltrations, and conventional inferior alveolar nerve anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2010, 109, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendrababu, V.; Ahmed, H.M.A.; Pulikkotil, S.J.; Veettil, S.K.; Dharmarajan, L.; Setzer, F.C. Anesthetic efficacy of Gow-Gates, Vazirani-Akinosi, and mental incisive nerve blocks for treatment of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1175–1183.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.; Reader, A.; Drum, M.; Nusstein, J.; Beck, M. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy of the conventional inferior alveolar, Gow-Gates, and Vazirani-Akinosi techniques. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 1306–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, A.; Clouet, R.; Boëffard, C.; Laham, A.; Martin, H.; Del Valle, G.A.; Enkel, B.; Prud’Homme, T. Comparing intraosseous computerized anesthesia with inferior alveolar nerve block in the treatment of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhad, A.; Razavian, H.; Shafiee, M. Effect of intraosseous injection versus inferior alveolar nerve block as primary pulpal anesthesia of mandibular posterior teeth with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizuela, M.; Daley, J.O. Inferior alveolar nerve block. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564368/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Tiwari, A. A traumatic ulcer caused by accidental lip biting following topical anesthesia: A case report. Cureus 2023, 15, e38316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmoeckel, J.; Ali, M.M.; Wolters, P.; Santamaria, R.M.; Usichenko, T.; Splieth, C.H. Pain perception during injection of local anesthesia in pedodontics. Quintessence Int. 2021, 52, 706–712. [Google Scholar]

- Renton, T. Optimal local anesthesia for dentistry. Prim. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.A. Local anesthesia for restorative dentistry. Gen. Dent. 2014, 62, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T.M.; Yagiela, J.A. Advanced techniques and armamentarium for dental local anesthesia. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 54, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Yoshida, H.; Yoshimura, H. A preliminary study on the assessment of pain using figures among patients administered with dental local anesthesia for mandibular third molar extraction. Medicine 2023, 102, e34598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kary, A.L.; Gomez, J.; Raffaelli, S.D.; Levine, M.H. Preclinical local anesthesia education in dental schools: A systematic review. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 82, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogle, O.E.; Mahjoubi, G. Advances in local anesthesia in dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 55, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, K. Intra-osseous anesthesia. Dent. Anaesth. Sedat. 1974, 3, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Surgical Procedure | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) | Total N = 85 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteotomy | 28 (42.4) | 20 (46.5) | 17 (45.9) | 65 (76.5) |

| Implantation | 29 (43.9) | 20 (46.5) | 12 (32.4) | 61 (71.8) |

| Root resection | 9 (13.6) | 3 (7.0) | 8 (21.6) | 20 (23.5) |

| Location | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) | Total N = 85 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxilla | 29 (43.9) | 5 (11.6) | 29 (78.4) | 65 (76.5) |

| Mandible | 37 (56.1) | 38 (88.4) | 8 (21.6) | 61 (71.8) |

| Number of Perforations | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 (68.2) | 22 (51.2) | 31 (83.8) |

| 2 | 21 (31.8) | 21 (48.8) | 6 (16.2) |

| Needle Obstruction | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 57 (86.4) | 40 (93.0) | 33 (89.2) |

| Yes | 9 (13.6) | 3 (3.5) | 4 (10.8) |

| Needle Change | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 58 (87.9) | 41 (95.3) | 34 (91.9) |

| Yes | 8 (12.1) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (8.1) |

| Lip Numbness | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 57 (86.4) | 9 (20.9) | 28 (75.7) |

| Yes | 9 (13.6) | 34 (79.1) | 9 (24.3) |

| Additional Injections | IO N = 66 (%) | IANB N = 43 (%) | INF N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 55 (83.3) | 37 (86.0) | 29 (78.4) |

| Yes | 11 (16.7) | 6 (14.0) | 8 (21.6) |

| Pain | IO Mean (StD) N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB Mean (StD) N = 43 (%) | INF Mean (StD) N = 37 (%) | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infiltration | 2.19 (0.69) | 2.43 (0.77) | 2.33 (1.02) | 0.661 | 0.452 | 0.592 |

| Perforation | 2.41 (0.76) | 3.49 (7.01) | 4.52 (9.32) | 0.336 | 0.274 | 0.974 |

| Instillation | 2.49 (0.65) | 2.49 (0.65) | 2.67 (0.84) | 1.0 | 0.135 | 0.421 |

| Treatment | 1.11 (0.31) | 1.13 (0.06) | 1.11 (0.22) | 0.324 | 1.0 | 0.98 |

| Post surgery | 1.41 (0.50) | 1.46 (0.51) | 1.19 (0.40) | 0.160 | 0.162 | 0.96 |

| 1-day post-surgery | 1.57 (0.50) | 1.62 (0.08) | 1.57 (0.51) | 0.161 | 1.0 | 0.331 |

| Pain | IO Mean (StD) N = 66 (%) | IANB/MNB Mean (StD) N = 43 (%) | INF Mean (StD) N = 37 (%) | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (RR sys mmHg) | 141 (18) | 143 (19) | 142 (14) | 0.298 | 0.558 | 0.400 |

| (RR dia mmHG) | 76 (10) | 74 (8) | 74. (4) | 0.647 | 0.307 | 1.0 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 80 (21) | 84 (22) | 81 (9) | 0.878 | 0.934 | 0.799 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nilius, M.H.; Nilius, M. Computer-Guided Intraosseous Anesthesia as a Primary Anesthetic Technique in Oral Surgery and Dental Implantology—A Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 572. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120572

Nilius MH, Nilius M. Computer-Guided Intraosseous Anesthesia as a Primary Anesthetic Technique in Oral Surgery and Dental Implantology—A Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):572. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120572

Chicago/Turabian StyleNilius, Minou Hélène, and Manfred Nilius. 2025. "Computer-Guided Intraosseous Anesthesia as a Primary Anesthetic Technique in Oral Surgery and Dental Implantology—A Pilot Study" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 572. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120572

APA StyleNilius, M. H., & Nilius, M. (2025). Computer-Guided Intraosseous Anesthesia as a Primary Anesthetic Technique in Oral Surgery and Dental Implantology—A Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 572. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120572