The Effect of Fermented Lingonberry Spray on Oral Health—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

- Does your mouth feel dry after eating?

- Do you have difficulty swallowing?

- Can you eat dry bread or cookies without drinking?

- Do you feel that saliva production is low?

- How often do you wake up at night due to feelings of dry mouth?

2.3. Tests

2.4. Clinical Examinations

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Statistics

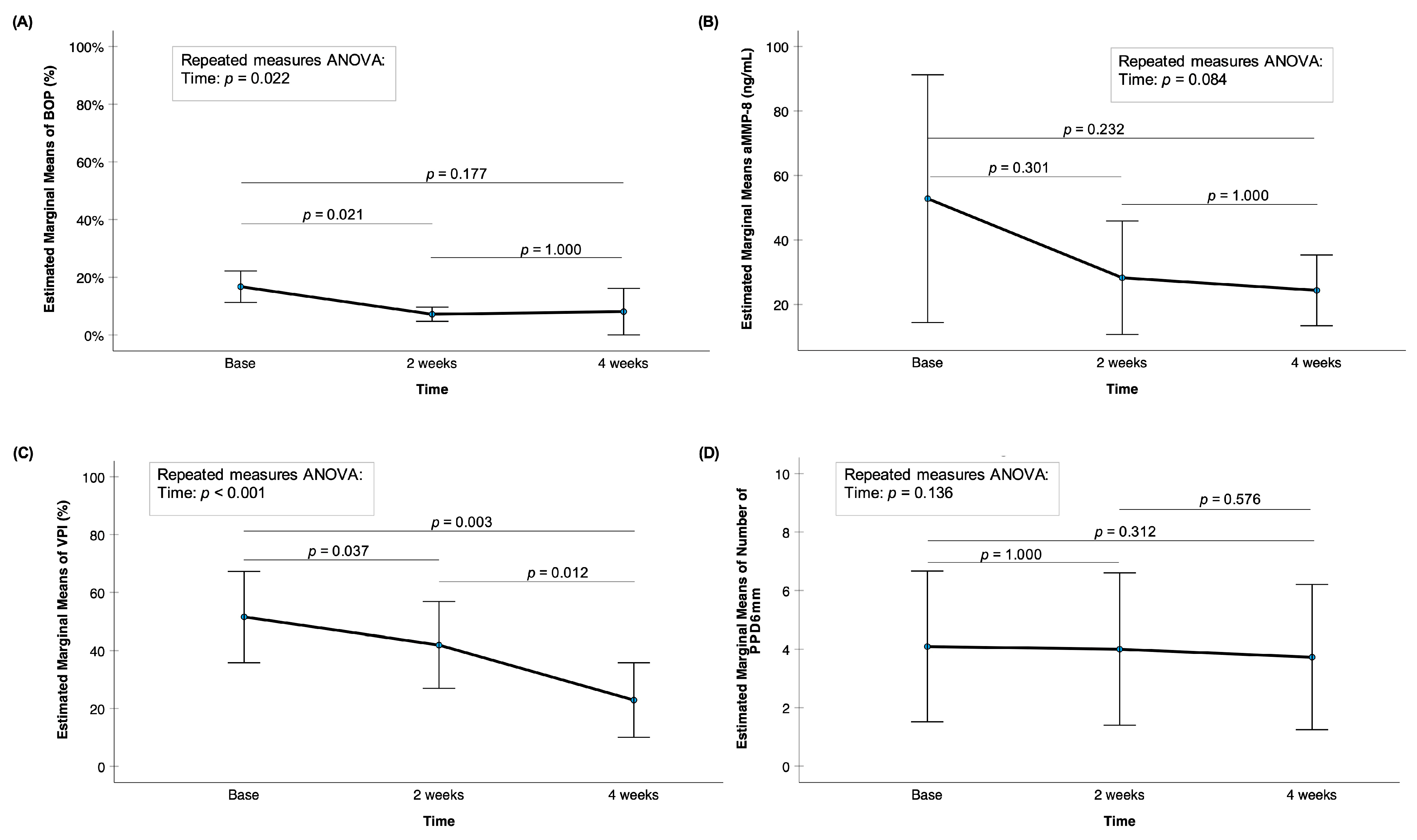

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Saliva/Xerostomia

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Explanation of Biological Mechanisms

4.3. Main Findings and Clinical Relevance

4.4. Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pärnänen, P.; Lähteenmäki, H.; Tervahartiala, T.; Räisänen, I.T.; Sorsa, T. Lingonberries—General and Oral Effects on the Microbiome and Inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnänen, P.; Lomu, S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Sorsa, T. Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Oral Effects of Fermented Lingonberry Juice-A One-Year Prospective Human Intervention Study. Eur J Dent. 2023, 17, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lähteenmäki, H.; Tervahartiala, T.; Räisänen, I.T.; Pärnänen, P.; Sorsa, T. Fermented lingonberry juice’s effects on active MMP-8 (aMMP-8), bleeding on probing (BOP), and visible plaque index (VPI) in dental implants—A clinical pilot mouthwash study. Clin. Exp. Den.T Res. 2022, 8, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnänen, P.; Lomu, S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Sorsa, T. Effects of Fermented Lingonberry Juice Mouthwash on Salivary Parameters—A One-Year Prospective Human Intervention Study. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuelli, M.; Marcolina, M.; Nardi, N.; Bertossi, D.; De Santis, D.; Ricciardi, G.; Luciano, U.; Nocini, R.; Mainardi, A.; Lissoni, A.; et al. Oral mucosal complications in orthodontic treatment. Minerva Stomatal. 2019, 68, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchese, A.; Carinci, F.; Brunelli, G.; Monguzzi, R. An in vitro study of resistance to corrosion in brazed and laser-welded orthodontic appliances. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2011, 9, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, R.G.; Silletti, E.; Vingerhoeds, M.H. Saliva as research material: Biochemical, physicochemical and practical aspects. Arch. Oral Biol. 2007, 52, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenander-Lumikari, M.; Loimaranta, V. Saliva and dental caries. Adv. Dent. Res. 2000, 14, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, E.; Campanati, A.; Diotallevi, F.; Offidani, A. Saliva and Oral Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzalaf, M.A.; Hannas, A.R.; Kato, M.T. Saliva and dental erosion. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, R.; Thomas, S.; Garla, B.; Dagli, R.J.; Hans, M.K. Effect of Various Sugary Beverages on Salivary pH, Flow Rate, and Oral Clearance Rate amongst Adults. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 5027283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Cheng, X.Q.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, P.; Yi, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.D. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 8, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Habobe, H.; Haverkort, E.B.; Nazmi, K.; Van Splunter, A.P.; Pieters, R.H.H.; Bikker, F.J. The impact of saliva collection methods on measured salivary biomarker levels. Clin. Chim Acta 2024, 552, 117628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorsa, T.; Tjäderhane, L.; Salo, T. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2004, 10, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorsa, T.; Gursoy, U.K.; Nwhator, S.; Hernandez, M.; Tervahartiala, T.; Leppilahti, J.; Gursoy, M.; Könönen, E.; Emingil, G.; Pussinen, P.J.; et al. Analysis of matrix metalloproteinases, especially MMP-8, in gingival creviclular fluid, mouthrinse and saliva for monitoring periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2016, 70, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsa, T.; Gieselmann, D.; Arweiler, N.B.; Hernández, M. A quantitative point-of-care test for periodontal and dental peri-implant diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017, 3, 17069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, I.T.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Siren, E.; Tervahartiala, T.; Gieselmann, D.R.; van der Schoor, G.J.; van der Schoor, P.; Sorsa, T. Point-of-Care/Chairside aMMP-8 Analytics of Periodontal Diseases’ Activity and Episodic Progression. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassiri, S.; Parnanen, P.; Rathnayake, N.; Johannsen, G.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Lazzara, R.; van der Schoor, P.; van der Schoor, J.G.; Tervahartiala, T.; Gieselmann, D.; et al. The Ability of Quantitative, Specific, and Sensitive Point-of-Care/Chair-Side Oral Fluid Immunotests for aMMP-8 to Detect Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 1306396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majid, A.; Alassiri, S.; Rathnayake, N.; Tervahartiala, T.; Gieselmann, D.R.; Sorsa, T. Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 as an Inflammatory and Prevention Biomarker in Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 7891323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsa, T.; Alassiri, S.; Grigoriadis, A.; Räisänen, I.T.; Pärnänen, P.; Nwhator, S.O.; Gieselmann, D.R.; Sakellari, D. Active MMP-8 (aMMP-8) as a Grading and Staging Biomarker in the Periodontitis Classification. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, H.; Umeizudike, K.A.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Räisänen, I.T.; Rathnayake, N.; Johannsen, G.; Tervahartiala, T.; Nwhator, S.O.; Sorsa, T. aMMP-8 Point-of-Care/Chairside Oral Fluid Technology as a Rapid, Non-Invasive Tool for Periodontitis and Peri-Implantitis Screening in a Medical Care Setting. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsa, T.; Bacigalupo, J.; Könönen, M.; Pärnänen, P.; Räisänen, I.T. Host-Modulation Therapy and Chair-Side Diagnostics in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Biosensors 2020, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, M.J.L.; Teeuw, W.J.; Bizzarro, S.; Muris, J.; Su, N.; Nicu, E.A.; Nazmi, K.; Bikker, F.J.; Loos, B.G. A rapid, non-invasive tool for periodontitis screening in a medical care setting. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnänen, P.; Nikula-Ijäs, P.; Sorsa, T. Antimicrobial and Anti-inflammatory Lingonberry Mouthwash—A Clinical Pilot Study in the Oral Cavity. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohynek, L.J.; Alakomi, H.L.; Kähkönen, M.P.; Heinonen, M.; Helander, I.M.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.M.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.H. Berry phenolics: Antimicrobial properties and mechanisms of action against severe human pathogens. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 54, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, M. Antioxidant activity and antimicrobial effect of berry phenolics—A Finnish perspective. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riihinen, K.R.; Ou, Z.M.; Gödecke, T.; Lankin, D.C.; Pauli, G.F.; Wu, C.D. The antibiofilm activity of lingonberry flavonoids against oral pathogens is a case connected to residual complexity. Fitoterapia 2014, 97, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva-Glomb, L.; Mukova, L.; Nikolova, N.; Badjakov, I.; Dincheva, I.; Kondakova, V.; Doumanova, L.; Galabov, A.S. In vitro antiviral activity of a series of wild berry fruit extracts against representatives of Picorna-, Orthomyxo- and Paramyxoviridae. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Sorsa, T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Nikula-Ijäs, P. Isolation, characterization and regulation of moonlighting proteases from Candida glabrata cell wall. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylli, P.; Nohynek, L.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Westerlund-Wikström, B.; Leppänen, T.; Welling, J.; Moilanen, E.; Heinonen, M. Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and European cranberry (Vaccinium microcarpon) proanthocyanidins: Isolation, identification, and bioactivities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3373–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, A.S.; Ehlers, P.I.; Siltari, A.; Turpeinen, A.M.; Vapaatalo, H.; Korpela, R. Lingonberry, cranberry and blackcurrant juices affect mRNA expressions of inflammatory and atherothrombotic markers of SHR in a long-term treatment. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, A.S.; Siltari, A.; Ehlers, P.I.; Korpela, R.; Vapaatalo, H. Lingonberry juice negates the effects of a high salt diet on vascular function and low-grade inflammation. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marungruang, N.; Kovalenko, T.; Osadchenko, I.; Voss, U.; Huang, F.; Burleigh, S.; Ushakova, G.; Skibo, G.; Nyman, M.; Prykhodko, O.; et al. Lingonberries and their two separated fractions differently alter the gut microbiota, improve metabolic functions, reduce gut inflammatory properties, and improve brain function in ApoE−/− mice fed high-fat diet. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttala, M.; Sorsa, T.; Thomas, J.T.; Grigoriadis, A.; Sakellari, D.; Sahni, V.; Gupta, S.; Pärnänen, P.; Pätilä, T.; Räisänen, I.T. Determination of the Stage of Periodontitis with 20 ng/mL Cut-Off aMMP-8 Mouth Rinse Test and Polynomial Functions in a Mobile Application. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (mean standard deviation) | 62.81 ± 14 |

| Sex (female/male %) | 27.3 /72.7 |

| Smoking /Snuff (Yes%) | 18 |

| Heart diseases (%) | 27.2 |

| Asthma (%) | 18 |

| Rheumatism (%) | 18 |

| Diabetes (%) | 9 |

| Saliva Samplings | Timepoint 1 | Timepoint 2 | Timepoint 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting saliva flow (N) | |||

| Low | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Normal | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Stimulated saliva (N) | |||

| Extremely low (<3.5 mL/min) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low (3.5–5.0 mL/min) | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Normal (>5.0 mL/min) | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Resting saliva pH (N) | |||

| Highly acidic (5–5.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderately acidic (6–6.6) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Healthy saliva (6.8–7.8) | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| Buffering capacity (N) | |||

| Very low (0–5) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Low (6–9) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal (10–12) | 6 | 7 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lähteenmäki, H.; Pärnänen, L.; Räisänen, I.T.; Sakko, M.; Pärnänen, P.; Sorsa, T. The Effect of Fermented Lingonberry Spray on Oral Health—A Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120568

Lähteenmäki H, Pärnänen L, Räisänen IT, Sakko M, Pärnänen P, Sorsa T. The Effect of Fermented Lingonberry Spray on Oral Health—A Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):568. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120568

Chicago/Turabian StyleLähteenmäki, Hanna, Leo Pärnänen, Ismo T. Räisänen, Marjut Sakko, Pirjo Pärnänen, and Timo Sorsa. 2025. "The Effect of Fermented Lingonberry Spray on Oral Health—A Pilot Study" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120568

APA StyleLähteenmäki, H., Pärnänen, L., Räisänen, I. T., Sakko, M., Pärnänen, P., & Sorsa, T. (2025). The Effect of Fermented Lingonberry Spray on Oral Health—A Pilot Study. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120568