Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Gingival Enlargement: Report of Two Representative Cases and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Reports

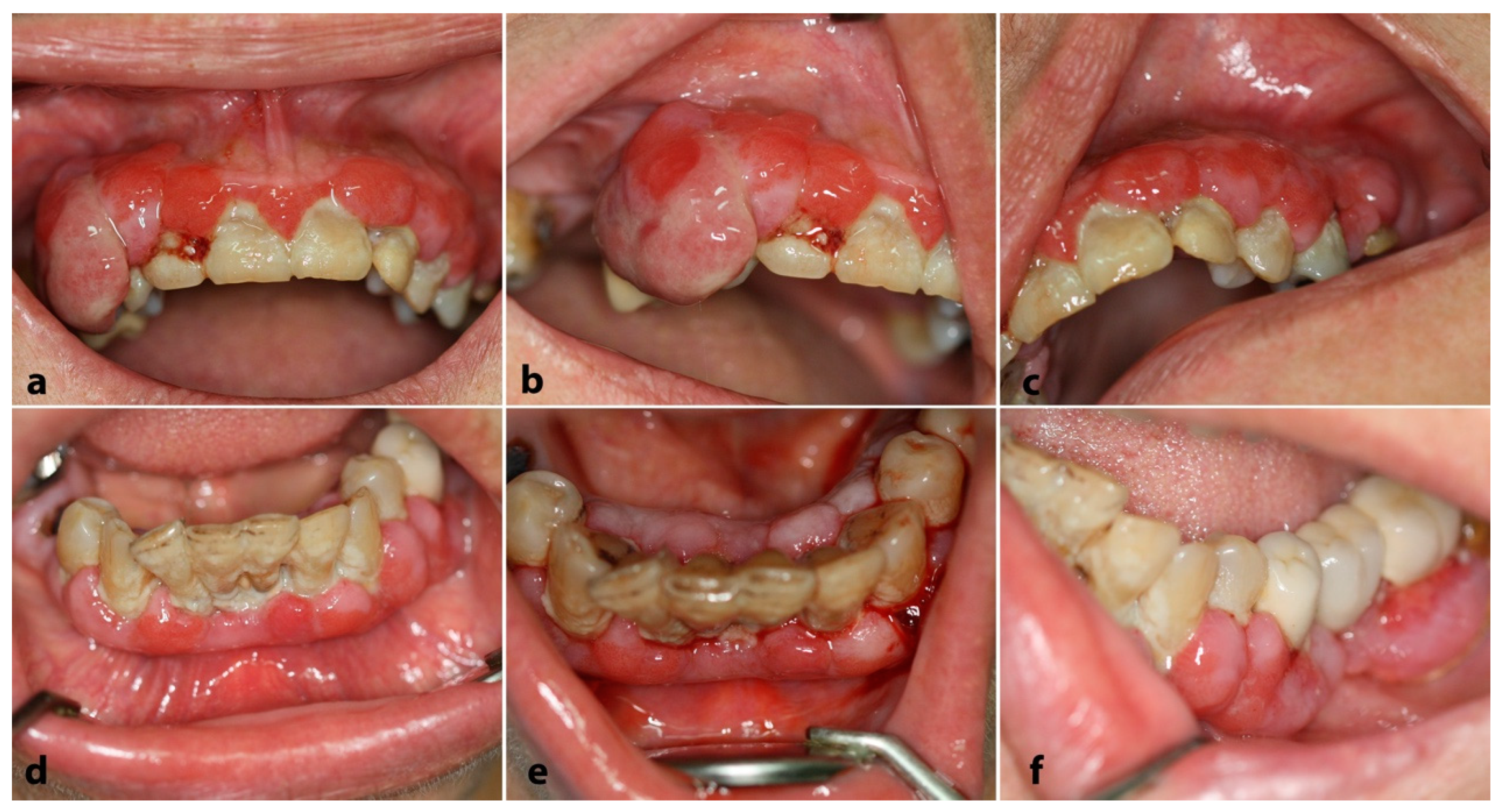

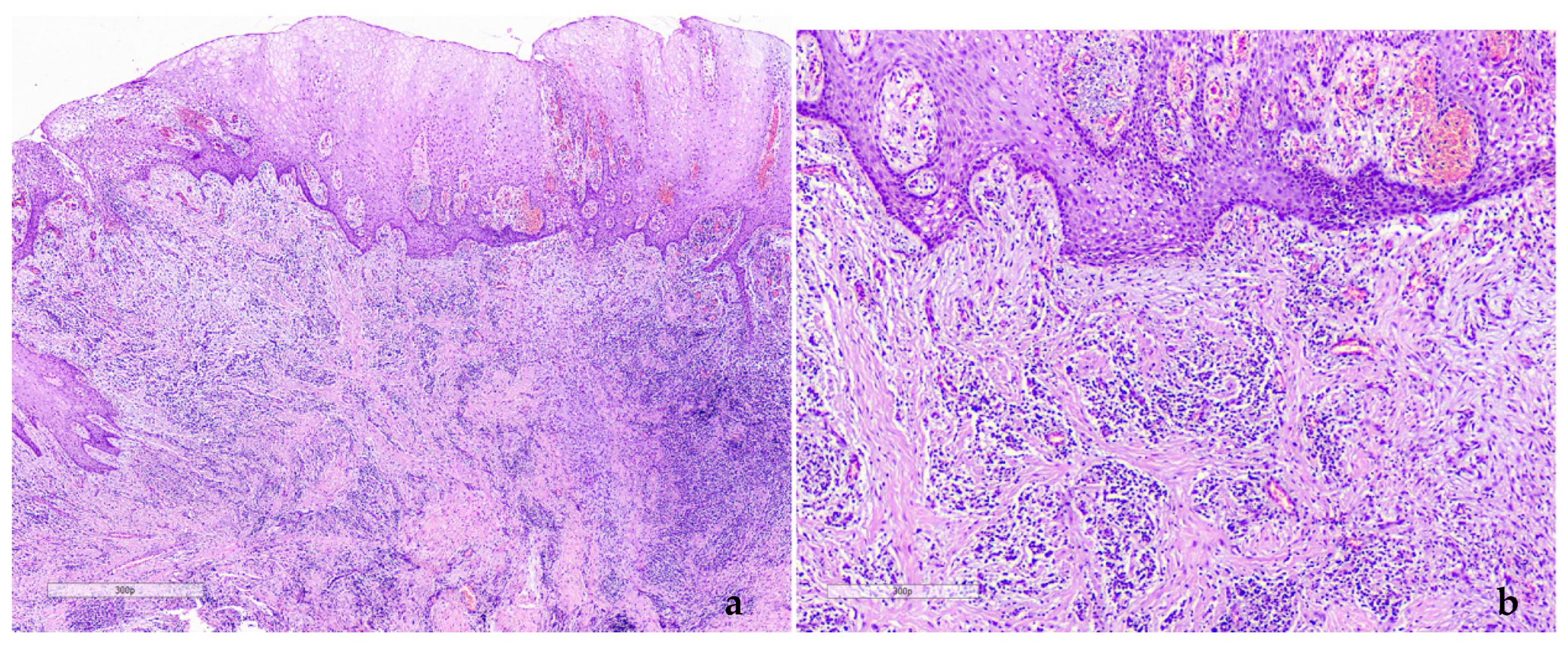

2.1. Case 1

2.2. Case 2

3. Discussion

- Hyperplastic gingivitis/periodontitis (association with local factors, diabetes mellitus, and/or hormonal imbalances)

- Drug-related gingival overgrowth

- Gingival fibromatosis

- iLeukemia

- Granulomatous gingivitis

- Spongiotic gingival hyperplasia (SGH)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis—Wegener’s granulomatosis

- Plasma cell gingivitis

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Scurvy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khera, P.; Zirwas, M.J.; English, J.C., 3rd. Diffuse gingival enlargement. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52 Pt 1, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsoum, F.; Prete, B.R.J.; Ouanounou, A. Drug-Induced Gingival Enlargement: A Review of Diagnosis and Current Treatment Strategies. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2022, 43, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.A. Gingival enlargements: Differential diagnosis and review of literature. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 16, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, H.; Furui, M.; Matsubara, T.; Inagaki, K. Gingival enlargement improvement following medication change from amlodipine to benidipine and periodontal therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 19, e249879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.W.; Jiang, S.Y. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 623427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, G.P. The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenyl hydrantoinate. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1939, 112, 1244–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livada, R.; Shiloah, J. Calcium channel blocker-induced gingival enlargement. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trackman, P.C.; Kantarci, A. Molecular and clinical aspects of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnaiyan, D.; Jegadeesan, V. Cyclosporine A: Novel concepts in its role in drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Dent. Res. J. 2015, 12, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.S.; Arany, P.R. Mechanism of drug-induced gingival overgrowth revisited: A unifying hypothesis. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, e51–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, W.H.; Gross, S.D. Case of hypertrophy of the gums. Dent. Regist. West. 1856, 9, 276–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, J.L.S.; Ramos, M.A.C.D.C.; Regis, D.M.; Sanchéz-Romero, C.; de Andrade, M.E.; Bezerra, B.T.; de Albuquerque-Júnior, R.L.C. Generalized hereditary gingival fibromatosis in a child: Clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. Autops. Case Rep. 2020, 21, e2020140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Falco, D.; Della Vella, F.; Scivetti, M.; Suriano, C.; De Benedittis, M.; Petruzzi, M. Non-Plaque Induced Diffuse Gingival Overgrowth: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, E.J.; Godoy, G.P.; Lins, R.D.; de Medeiros, A.M.; Queiroz, L.M. Partial facial hemihyperplasia with 9 years of evolution: Case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 102, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Tandon, S.; Sharma, M.; Vijay, A. Nonsyndromic Gingival Fibromatosis: A Rare Case Report. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 11, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.C.; Pallos, D.; Bozzo, L.; Almeida, O.P.; Marazita, M.L.; O’Connell, J.R.; Cortelli, J.R. Evidence of genetic heterogeneity for hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J. Dent. Res. 2000, 79, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.C.; Arora, A.; Arora, S. Oral Manifestations as an Early Clinical Sign of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Report of Two Cases. Indian J. Dermatol. 2020, 65, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Khan, N.I.; Reddy, L.B. Leukemic gingival enlargement: Report of a rare case with review of literature. Int. J. Appl. Basic. Med. Res. 2015, 5, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreizen, S.; McCredie, K.B.; Keating, M.J.; Luna, M.A. Malignant gingival and skin “infiltrates” in adult leukemia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1983, 55, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.C.; Kim, C.S. Oral signs of acute leukemia for early detection. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2014, 44, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, R.; Yang, X.; Wei, H. Molecular landscape and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Biomark. Res. 2018, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, A. Hematological malignancies and molecular targeting therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 862, 172641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhassani, A.A.; Al-Zahrani, M.S.; Zawawi, K.H. Granulomatous diseases: Oral manifestations and recommendations. Saudi Dent. J. 2020, 32, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthuraj, M.S.A.; Maradi, A.P.; Janakiram, S.; Chithresan, K. Tuberculous gingival enlargement: A rare clinical manifestation. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2017, 21, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhithya, N.; Babu, S.P.K.K.; Paul, G.T.; Soorya, K.V. Gingiva as the primary site of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A rare case report with brief review of literature. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2024, 28, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiwala, S.A.; Dixit, M.B. Gingival enlargement unveiling sarcoidosis: Report of a rare case. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2013, 4, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galohda, A.; Shreehari, A.K. Orofacial granulomatosis as a manifestation of sarcoidosis: A rare case report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2023, 27, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchin-Albertoni, C.; Pieruccioni, L.; Canceill, T.; Benetah, R.; Chaumont, J.; Guissard, C.; Monsarrat, P.; Kémoun, P.; Marty, M. Gingival Orofacial Granulomatosis Clinical and 2D/3D Microscopy Features after Orthodontic Therapy: A Pediatric Case Report. Medicina 2023, 59, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarra, A.; Nikitakis, N.G.; Daskalopoulos, A.; Chouliaras, G.; Sklavounou-Andrikopoulou, A.; Athanasaki, K. Orofacial granulomatosis as early manifestation of Crohn’s disease: Report of a case in a paediatric patient. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2016, 17, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, J.D.; Cheifetz, A.S. Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.C.; Daley, T.D. Foreign body gingivitis: Clinical and microscopic features of 61 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1997, 83, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.; Peng, H.H.; Cox, D.P.; Chambers, D.W.; Bhula, A.; Young, J.D.; Ojcius, D.M.; Ramos-Junior, E.S.; Morandini, A.C. Investigation of foreign materials in gingival lesions: A clinicopathologic, energy-dispersive microanalysis of the lesions and in vitro confirmation of pro-inflammatory effects of the foreign materials. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, M.R.; Daley, T.D.; Wilson, A.; Wysocki, G.P. Juvenile spongiotic gingivitis. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, R.J.; Bilodeau, E.A. Reappraising localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 147–153.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Z.; Jordan, R.C. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: A report of 27 cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2019, 46, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilou, V.I.; Pettas, E.; Georgaki, M.; Daskalopoulos, A.; Nikitakis, N.G. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: Microscopic variations and proposed change to nomenclature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 131, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, I.; Lammert, K.M.; Iwase, R.; Spears, R.; Wright, J.M.; Naidu, A. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia possibly originates from the junctional gingival epithelium-an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 2016, 68, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.Y.; Kessler, H.P.; Wright, J.M. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008, 106, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalkari, C.D.; Patil, S.C.; Indurkar, M.S. Strawberry gingivitis—First sign of Wegener’s granulomatosis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2020, 24, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ponniah, I.; Shaheen, A.; Shankar, K.A.; Kumaran, M.G. Wegener’s granulomatosis: The current understanding. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2005, 100, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, J.C.; Grayson, P.C.; Ponte, C.; Suppiah, R.; Craven, A.; Judge, A.; Khalid, S.; Hutchings, A.; Watts, R.A.; Merkel, P.A.; et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/ European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Athritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilly, J.; Juhlin, T.; Lew, D.; Vincent, S.; Lilly, G. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as oral lesions: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1998, 85, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, V.; Hall, T.J. Strawberry gingival enlargement as only manifestation of Wegeners granulomatosis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 47, 500. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, S.V.; Nico, M.M. Strawberry gingivitis: An isolated manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis? Acta Derm. Venereol. 2006, 86, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, M.; Fröhlich, L.F.; Kleinheinz, J. Gingival hyperplasia as first sign of recurrence of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): Case report and review of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2016, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanya, A.P.; George, J.P.; Prabhuji, M.L.V.; Bavle, R.M.; Muniswamappa, S. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in gingiva: A rare case of isolated presentation. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2022, 11, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, R.H.; Georgaki, M.; Nikitakis, N.G. Plasma Cell Gingivitis and Its Mimics. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 35, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janam, P.; Nayar, B.R.; Mohan, R.; Suchitra, A. Plasma cell gingivitis associated with cheilitis: A diagnostic dilemma! J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2012, 16, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Leuci, S.; Coppola, N.; Adamo, N.; Bizzoca, M.E.; Russo, D.; Spagnuolo, G.; Lo Muzio, L.; Mignogna, M.D. Clinico-Pathological Profile and Outcomes of 45 Cases of Plasma Cell Gingivitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 18, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, B.S.; Kumar, N.R.; Haris, P.S.; Yogesh, J.A.; Vijayalakshmi, C.; James, J. Plasma-Cell Gingivitis a Challenge to the Oral Physician. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesarman, E.; Damania, B.; Krown, S.E.; Martin, J.; Bower, M.; Whitby, D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 31, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Cesarman, E.; Pessin, M.S.; Lee, F.; Culpepper, J.; Knowles, D.M.; Moore, P.S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science 1994, 16, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messeca, C.; Balanger, M.; Geoffroy, F.; Duval, X.; Samimi, M.; Millot, S. Oral Kaposi Sarcoma in two patients living with HIV despite sustained viral suppression: New clues. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 1, e453–e456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerson, E.; Buziba, N.; Wabinga, H.; Wenger, M.; Bwana, M.; Muyindike, W.; Kyakwera, C.; Laker, M.; Mbidde, E.; Yiannoutsos, C.; et al. Diagnosing Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) in East Africa: How accurate are clinicians and pathologists? Infect. Agents Cancer 2012, 7, P6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpidis, C.D.; Lysitsa, S.N.; Lombardi, T.; Kolokotronis, A.E.; Antoniades, D.Z.; Samson, J. Gingival involvement in a case series of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbe, C.; Garbe, C.; Stratigos, A.J.; Harwood, C.; Peris, K.; Marmol, V.D.; Malvehy, J.; Zalaudek, I.; Hoeller, C.; Dummer, R.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline (EDF/EADO/EORTC). Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 114, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epeldegui, M.; Chang, D.; Lee, J.; Magpantay, L.I.; Borok, M.; Bukuru, A.; Busakhala, N.; Godfrey, C.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Kang, M.; et al. Predictive Value of Serum Biomarkers for Response of Limited-Stage AIDS-Associated Kaposi Sarcoma to Antiretroviral Therapy With or Without Concomitant Chemotherapy in Resource-Limited Settings. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2023, 94, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, K.; Hanayama, Y.; Naruishi, K.; Akiyama, K.; Maeda, H.; Otsuka, F.; Takashiba, S. Gingival overgrowth caused by vitamin C deficiency associated with metabolic syndrome and severe periodontal infection: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2014, 2, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacci, M.; Gold, W.L.; Shah, R. Modern-day scurvy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 27, E96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japatti, S.R.; Bhatsange, A.; Reddy, M.; Chidambar, Y.S.; Patil, S.; Vhanmane, P. Scurvy-scorbutic siderosis of gingiva: A diagnostic challenge—A rare case report. Dent. Res. J. 2013, 10, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Velandia, B.; Centor, R.M.; McConnell, V.; Shah, M. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entity | Biofilm Correlation | Medical and Drug History | Clinical Findings | Microscopic Features | Diagnostic Procedure | Treatment Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperplastic gingivitis/periodontitis | Yes (strong) | Non-contributory (or co-existence of contributing factors) | Enlarged, erythematous and hemorrhagic gingiva, periodontal pockets (in periodontitis) | Non-pathognomonic; chronic or mixed inflammatory infiltrate; abundant granulation tissue and fibrosis | Clinical and radiographic evaluation | Periodontal treatment and oral hygiene improvement; surgical recontouring (if necessary) |

| DM-associated hyperplastic gingivitis/periodontitis | Yes | DM (poorly controlled; elevated blood glucose and/or HbA1C levels) | Same as above (other oral manifestations of DM may co-exist, e.g., candidiasis, xerostomia, RAS) | Same as above | Clinical and radiographic evaluation; appropriate laboratory tests for DM assessment | Periodontal treatment and oral hygiene improvement; pharmacologic and/or dietary management of DM |

| Hormonal imbalance-associated hyperplastic gingivitis/periodontitis | Yes | Puberty, pregnancy | Same as above (pyogenic granuloma-like lesions may occur, especially in pregnancy, i.e., “pregnancy tumors”) | Same as above | Clinical and radiographic evaluation | Periodontal treatment and oral hygiene improvement |

| Drug-related gingival overgrowth | Yes (variable) | Anti-convulsants, CCBs, cyclosporin, oral contraceptives | Enlarged gingiva of erythematous, hemorrhagic, and/or firm/fibrous consistency; may occasionally resemble pyogenic granulomas | Non-specific; hyperplastic fibrous connective and/or granulation tissue, chronic inflammation of variable degree | Medical history, clinical and radiographic examination | Periodontal treatment and oral hygiene improvement, gingivectomy, discontinuation or replacement of medication |

| Gingival fibromatosis | No | Hereditary, onset in childhood; hypertrichosis, epilepsy, intellectual disability, hypothyroidism, clondrodystrophia, growth hormone deficiency | Bilateral and symmetrical gingival enlargement; gingiva are of normal hue | Hyperplastic densely collagenized fibrous connective tissue with scattered fibroblasts and absent or mild inflammation | Medical and family history, clinicopathologic correlation | Surgical excision, oral hygiene improvement, periodontal treatment |

| Leukemia (with gingival infiltrate) | Weak | “B-symptoms” may be present | Gingiva usually described as “boggy” and hemorrhagic; ulcers, petechiae, and/or ecchymoses may co-exist | Tissue infiltration by atypical cells with myelomonocytic or lymphoid characteristics | CBC, BM biopsy, gingival biopsy and histopathologic examination, IHC and molecular analysis | Chemotherapy, targeted agents, BM transplantation |

| Granulomatous gingivitis | Very weak | Non-contributory in OFG and foreign body-related; possible history, signs, and symptoms of systemic granulomatous diseases (Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis) | Enlarged, erythematous gingiva; persistent, possibly symptomatic; other possible oral manifestations (swollen lips, cobblestone mucosal appearance, mucosal tags, linear ulcerations, fissured tongue) | Granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells (caseous necrosis in tuberculosis, polarizable foreign material in foreign body gingivitis) | Medical history, biopsy and histopathologic examination (special stains), specific work-up (e.g., chest X-ray, culture, endoscopy/colonoscopy, other laboratory tests) | Topical, intralesional, or systemic corticosteroids, other immunosuppressants; elimination diet (for OFG or Crohn’s); surgical recontouring (if there is no response to medications); management of the underlying systemic condition |

| Spongiotic gingival hyperplasia | No | None | Red sessile lesions with velvet or pebbly surface and soft consistency | Lack of keratinization, spongiosis, exocytosis, mixed inflammatory infiltration | Clinicopathologic correlation, IHC evaluation (CK19 and CK8/18) | Surgical excision, recurrences may occur (no response to oral hygiene measures) |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) | No | Sinonasal signs and symptoms; renal and respiratory tract involvement | “Strawberry-like” gingivitis, oral ulcerations may be also present | Granulomatous inflammation including multinucleated giant cells, necrosis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis (rarely seen in oral biopsy material) | Clinicopathologic correlation, radiographic evaluation (chest, sinus), laboratory tests (including PR3-ANCA or c-ANCA) | Corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and/or other immunosuppressants |

| Plasma cell gingivitis | Weak | Variable allergens (e.g., chewing gums, toothpaste, mouthwashes, spices); idiopathic | Rapid onset, enlarged brightly erythematous gingiva with loss of normal stippling, possibly symptomatic (burning sensation) | Dense inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells (polyclonal) | Clinicopathologic correlation, IHC evaluation (κ or λ light chains and CD138) | Modification of diet and/or oral hygiene products, topical or systemic immunosuppressive medications |

| Kaposi sarcoma | No | Immunosuppression, especially in HIV infection | Purplish-blue gingival enlargement, hemorrhagic | Proliferation of pleomorphic spindle cells forming slit-like vascular spaces | Clinicopathologic correlation, IHC evaluation, medical work-up | Chemotherapy (intralesional or systemic), topical therapies, surgical excision |

| Scurvy | Mild | Diet lacking fruits and vegetables, infants only feeding on milk, older men | Enlarged, erythematous, hemorrhagic, and fragile gingiva; tooth mobility; mucosal petechiae and ecchymoses | Non-specific | Vitamin C deficiency upon biochemical analysis | Replacement therapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadopoulou, E.; Kouri, M.; Andreou, A.; Diamanti, S.; Georgaki, M.; Katoumas, K.; Damaskos, S.; Vardas, E.; Piperi, E.; Nikitakis, N.G. Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Gingival Enlargement: Report of Two Representative Cases and Literature Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120403

Papadopoulou E, Kouri M, Andreou A, Diamanti S, Georgaki M, Katoumas K, Damaskos S, Vardas E, Piperi E, Nikitakis NG. Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Gingival Enlargement: Report of Two Representative Cases and Literature Review. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(12):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120403

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadopoulou, Erofili, Maria Kouri, Anastasia Andreou, Smaragda Diamanti, Maria Georgaki, Konstantinos Katoumas, Spyridon Damaskos, Emmanouil Vardas, Evangelia Piperi, and Nikolaos G. Nikitakis. 2024. "Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Gingival Enlargement: Report of Two Representative Cases and Literature Review" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 12: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120403

APA StylePapadopoulou, E., Kouri, M., Andreou, A., Diamanti, S., Georgaki, M., Katoumas, K., Damaskos, S., Vardas, E., Piperi, E., & Nikitakis, N. G. (2024). Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Diffuse Gingival Enlargement: Report of Two Representative Cases and Literature Review. Dentistry Journal, 12(12), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120403