Modelling the Process to Access the Spanish Public University System Based on Structural Equation Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

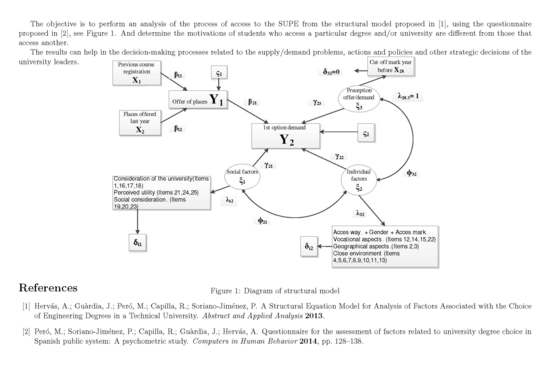

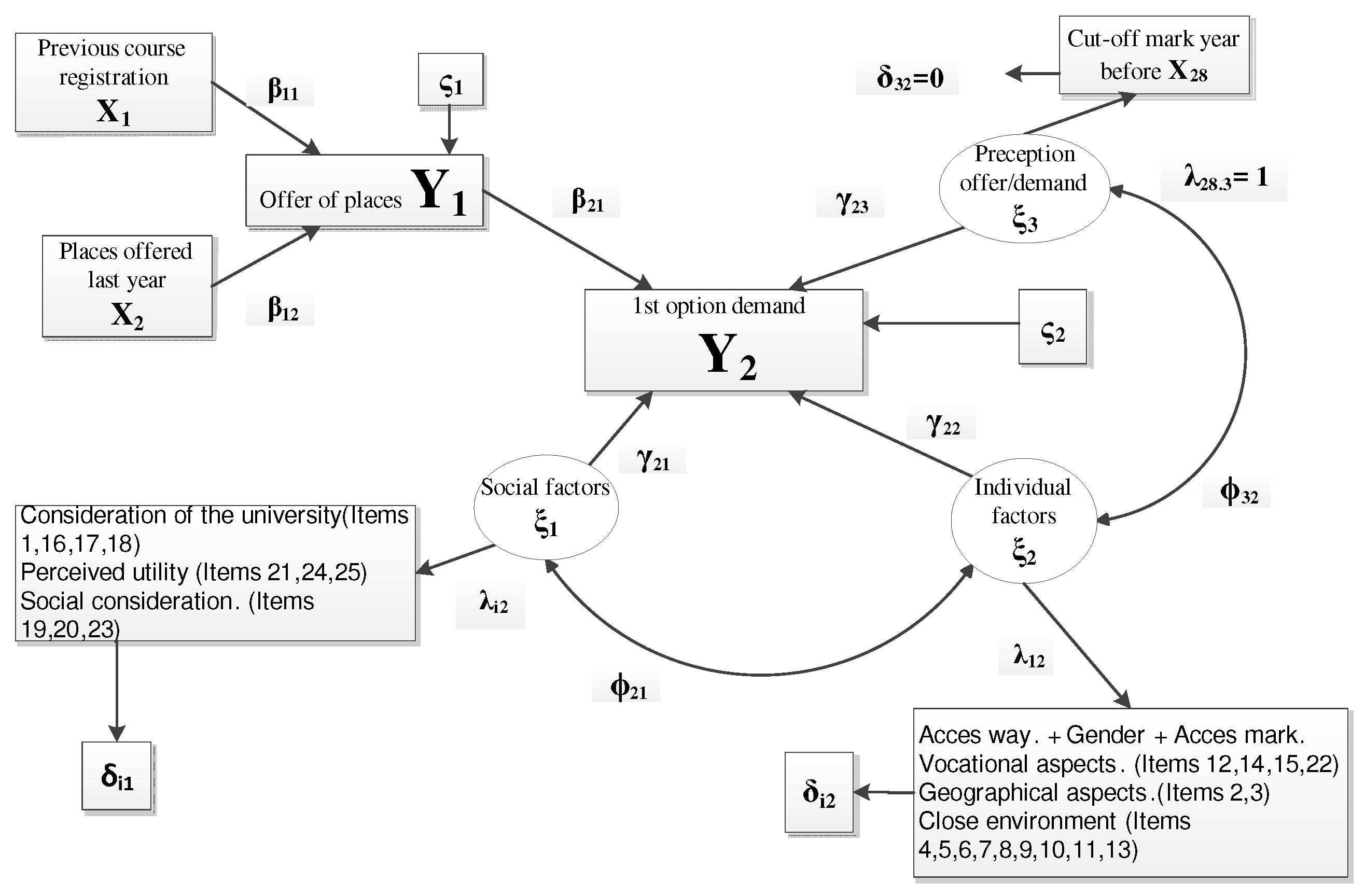

- Context dataAs the work of [35,37] has shown in this process, there are factors associated with the preinscription mechanism in Spain, such as the degree cut-off marks, the number of seats offered in each degree and even the gender of the students, as the selections for the first option are not independent of that variable.

- Individual factors

- Vocational aspects.

- Influence of the surrounding environment.

- Geographic location.

- Social factors

- University consideration.

- Perceived employability.

- Social consideration.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instrument

- Minimize the vertical scrolling of the survey pages. Ensure that the questions in each section will be covered at a glance.

- Give information about the position of the question in the survey set.

- The respondent knew at any time the total number of unanswered questions.

- Minimize the number of questions that needed to use a keyboard.

4. Results

4.1. Indicators for Adjusting the Model Parameters

Estimation of the Structural Parameters

- The is the lowest among the branches (0.543), and thus the sensitivity to changes in the perception of supply and demand is the lowest.

- The is the lowest among the branches; thus, the sensitivity to enhance social factors has an expected effect of only 0.344 standard deviations in the demand for each standard deviation that can improve the perception of these factors.

- The is the highest among the branches, with a value of 0.651. The efforts to improve the perception of individual factors among students demanding a degree will have a maximum impact on this group of degrees.

4.2. Detail of the Adjustment Indicators for Universities, Branches, and Grades

5. Discussion

- The realization of a new institutional survey that would allow us to obtain a not asymmetric and adjusted sample to the number of students of the SUPE. Clearly, this is far from our possibilities and could only be approached with institutional leadership at the highest level that allows for the technical and human capacity to produce this new survey.

- To develop a simulator from the model that allows university managers to adjust the values of the parameters, to be able to analyze the results, and thus, have a vision of the problem adapted to their needs.

- To periodically conduct the study. This would allow us to have tools to analyze the behavior of the parameters over time, as there are many factors that influence the student’s choice, and the temporal evolution could make any of the conditions vary.

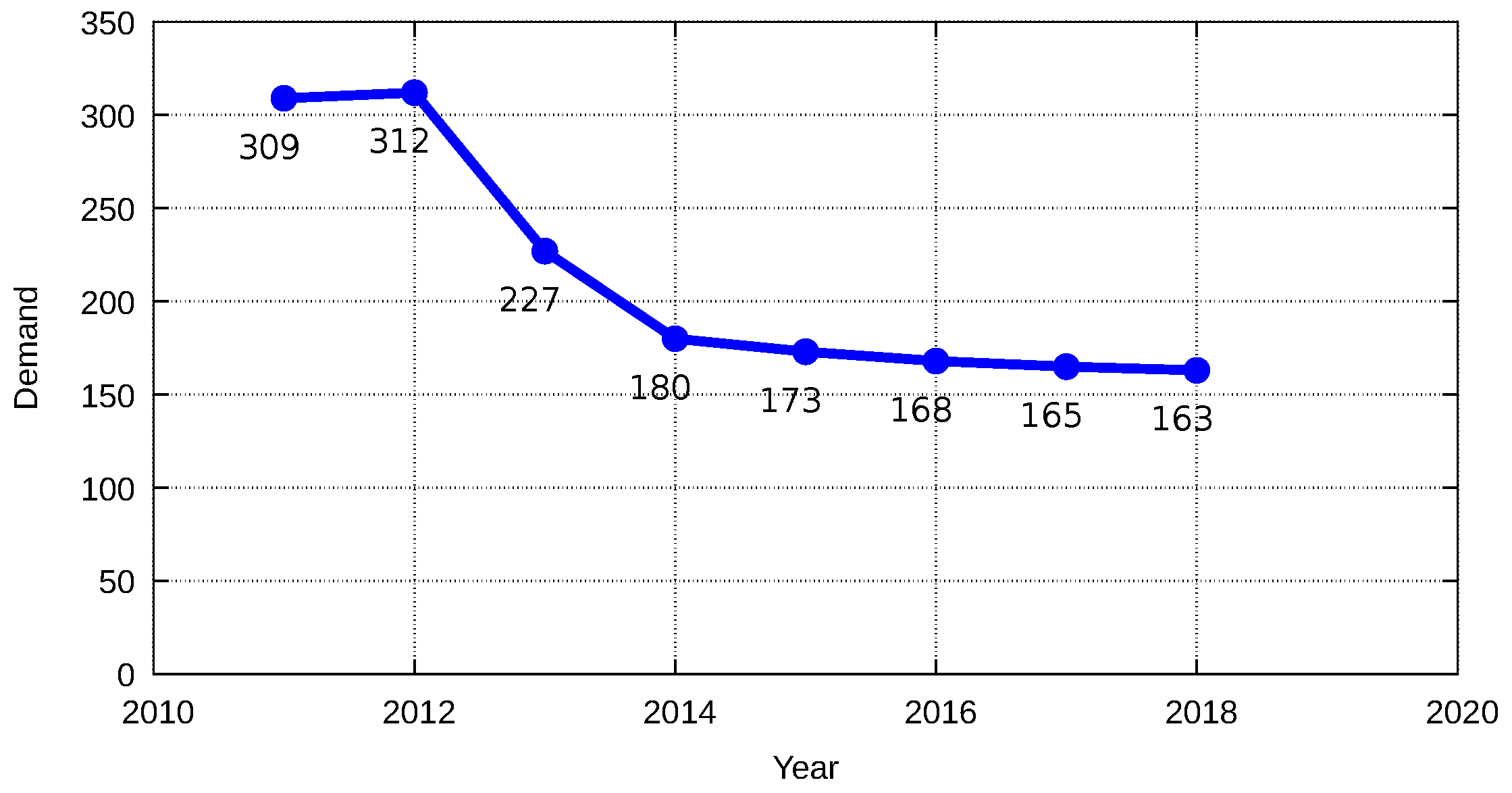

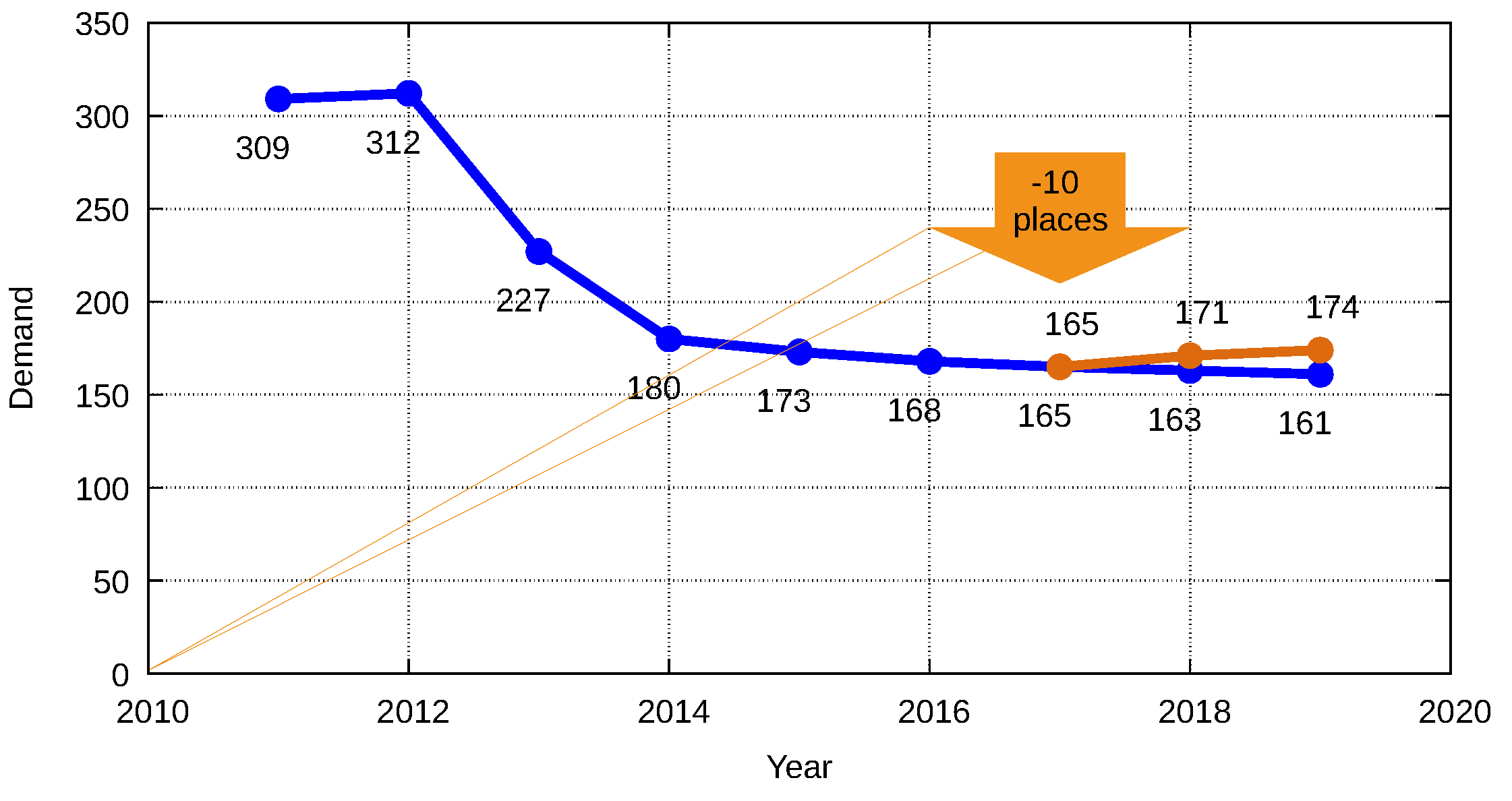

6. A Case Study

- Propose a value for the set of social factors resulting from the closing event, based on the values for the degree in geographical areas in which the current conditions are similar to those that would result from the event.

- Calculate the model parameters that allow us to estimate the effects of the closing event on the demand ( ).

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index |

| BBNFI | Bentler Bonnet Normed Fit Index |

| BBNNFI | Bentler Bonnet Non-Normed Fit Index |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| DF | Degrees of Freedom |

| EBAU | Spanish Baccalaureate Assessment for University Access |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| MECyD | Spanish Ministry of Education and Science |

| NCEE | Chinese National College Entrance Examination |

| PAU | Spanish entrance examination |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RUCT | Spanish Register of Universities, Centers and Degrees |

| SRMSE | Standardized Root Mean Square Error |

| SUPE | Spanish Public University System |

References

- Naylor, R.A.; Smith, J. Determinants of Educational Success in Higher Education; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Northampton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 415–461. [Google Scholar]

- Belvis, E.; Moreno, M.V.; Ferrer, F. Explanatory Factors for the Academic Success and Failure in Spanish Universities during the Process towards European Convergence. Rev. Española Educ. Comp. 2009, 1, 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- George, S.; Long, P. Penetrating the Fog: Analytics in Learning and Education. EDUCAUSE Rev. 2011, 46, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Cristobal, R.; Ventura, S. Educational data mining: A survey from 1995 to 2005. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 33, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Behrouz, M.B.; Kashy, D.A.; Kortemeyer, G.; Punch, W.F. Predicting student performance: An application of data mining methods with an educational web-based system. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Frontiers in Education, Westminster, CO, USA, 5–8 November 2020; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, G.; Rueda, E.M. Estudio Longitudinal de los Jóvenes en el Tránsito de la Enseñanza Secundaria a la Universidad: Orientación, Expectativas, Toma de Decisiones y Acogida de los Nuevos Estudiantes en la Universidad; Dirección General de Universidades, Estudios y Análisis: Valladolid, Spain, 2005; Available online: https://fracasoacademico.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/estudio-transito-a-universidad-_completo.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Capilla, R. Análisis Estratégico de los Estudios TIC en la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, L.W.; Titus, M.A. Understanding differences in the choice of college attended: The role of state public policies. Rev. High. Educ. 2004, 27, 501–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, I.F.; Matzdorf, F.; Smith, L.; Agahi, H. The impact of facilities on student choice of university. Facilities 2003, 21, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratacós, G.; López-Jurado, M. Validation of the Spanish Version of the Factors Influencing Teaching (FIT)-Choice scale. Revista de Educación 2016, 1, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, M. University and course choice: Implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 466–479. [Google Scholar]

- Oner, Y.H. How does the image of engineering affect student recruitment and retention? A perspective from the USA. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2002, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, J.; Mathers, J.; Stevens, A.; Parsons, A.; Lilford, R.; Spurgeon, P.; Thomas, H. Admissions processes for five year medical courses at English schools: Review. Br. Med. J. 2006, 332, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Kolster, R. Intl Student Recruitment: Policies and Developments in Selected Countries. Available online: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/international-student-recruitment-policies-and-developments-in-se (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Shane, D.; Macfadyen, L.; Lockyer, L.; Mazzochi-Jones, D. Using social network metrics to assess the effectiveness of broad based admission practices. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 27, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- P-Nuffic. The Chinese Education System Described and Compared with the Dutch System. Available online: https://www.nuffic.nl/en/publications/education-system-china/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- P-Nuffic. Information about the Education System of South Korea and the Evaluation of Degrees Obtained in South Korea. Available online: https://www.nuffic.nl/documents/491/education-system-south-korea.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- P-Nuffic. The American Education System Described and Compared with the Dutch System. Available online: https://www.nuffic.nl/en/publications/education-system-united-states/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Murphy, P.E.; McGarrity, R.A. Marketing universities: A survey of student recruitment activities. Coll. Univ. 1978, 53, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, D.Y. The underrepresentation of minority students in gifted education: Problems and promises in recruitment and retention. J. Spec. Educ. 2008, 31, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppel, K.; Williams, M.L.; Waldauer, C. The Impact of Parental Occupation and Socioeconomic Status on Choice of College Major. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2001, 22, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.S.V.; Thompson, J.R. Socializing Women Doctoral Students: Minority and Majority Experiences. Rev. High. Educ. 1993, 16, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, A.H.; Whetten, J.; Huffman, W.H. Using technology in higher education: The influence of gender roles on technology self-efficacy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misran, N.; Nurhanum-Syed-Sahuri, S.; Arsad, N.; Hussain, H.; Diyana-Wan-Zaki, W.M.; Aziz, N.A. The Influence of Socio-Economic Status among Matriculation Students in Selecting University and Undergraduate Program. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Serrano, G. Nuevos enfoques para la gestión estratégica de I+D e innovación en las universidades. Revista de Educación Ministerio de Educación Centro de Publicaciones 2011, 1, 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Research and practice of student retention: What next? J. Coll. Stud. Retent.: Res. Theory Pract. Baywood 2006, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Datos y Cifras del Sistema Universitario Español. Available online: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:aa35d8fe-ffbd-4142-8cca-9a093cc1d9de/datos-y-cifras-del-sue-curso-2014-2015.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- P-Nuffic. The Spanish Education System Described and Compared with the Dutch System. Available online: https://www.nuffic.nl/en/publications/education-system-spain/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Plan de Captación de Estudiantes. Available online: http://www.ff.ulpgc.es/system/files/plan_captacion_estudiantes._2017-2018.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Universidad Politècnica de València. Orientación: Actividades para Secundaria. Available online: http://www.upv.es/contenidos/ORIENTA/info/794644normalc.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Universitat Politècnica de Valencia. Campus Praktikum UPV. Available online: http://www.upv.es/contenidos/PRAKTIKUM/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Universidad Politècnica de València. Programa Valentina. 2007. Available online: http://www.valentinas.upv.es/proyecto_valentina_upv.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Real Academia de Ingeniería. Mujer e Ingeniería. Available online: http://www.raing.es/es/actividades/presentaci-n-del-proyecto-mujer-e-ingenier (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Universidad de Murcia. Servicios de Información y Orientación Universitarios. Available online: http://www.um.es/web/siou/inicio (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Hervás, A.; Guàrdia, J.; Peró, M.; Capilla, R.; Soriano-Jiménez, P. A Structural Equation Model for Analysis of Factors Associated with the Choice of Engineering Degrees in a Technical University. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2013, 2013, 368529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peró, M.; Soriano-Jiménez, P.; Capilla, R.; Guàrdia, J.; Hervás, A. Questionnaire for the assessment of factors related to university degree choice in Spanish public system: A psychometric study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 47, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guàrdia, J.; Peró, M.; Hervás, A.; Capilla, R.; Soriano-Jiménez, P.; Porras, M. Factors related with the university degree selection in Spanish public university system. An structural equation model analysis. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 541–557. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.; Lomax, R. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, J. Utilización de los tests. In Análisis de los Items; Muñiz, J., Fidalgo, A., García-Cueto, E., Martínez, R., Moreno, R.E., Eds.; Editorial La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 133–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, A.; Soriano Jiménez, P.P.; Iranzo, J.; Lemus Zúñiga, L.G.; Ivorra Martínez, E. A web-based application tool for university career choosing factors analysis. In Proceedings of the Mathematical Modelling in Engineering & Human Behaviour, Valencia, Spain, 19 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Indices | Arts n = 319 | Science n = 211 | Health n = 545 | Social n = 797 | Engineering n = 3239 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.941 | 0.977 | 0.953 | 0.944 | 0.974 |

| Adjusted Goodness | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.955 | 0.946 | 0.986 |

| of Fit Index (AGFI) | |||||

| Bentler Bonnet Normed | 0.931 | 0.955 | 0.949 | 0.955 | 0.975 |

| Fit Index (BBNFI) | |||||

| Bentler Bonnet Non-Normed | 0.912 | 0.962 | 0.948 | 0.962 | 0.982 |

| Fit Index (BBNNFI) | |||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.920 | 0.933 | 0.923 | 0.929 | 0.959 |

| Coefficient of determination (R2) | 0.387 | 0.472 | 0.512 | 0.489 | 0.512 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.003 |

| Standardized Root | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Mean Square Error (SRMSE) | |||||

| with df = 321 | 783.24 | 889.17 | 722.25 | 780.24 | 923.24 |

| Ratio / df | 2.44 | 2.77 | 2.25 | 2.44 | 2.99 |

| Latent Factor Reliability Values | Arts n = 319 | Science n = 211 | Health n = 545 | Social n = 797 | Engineering n = 3239 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consideration of the university | = 0.723 | = 0.779 | = 0.823 | = 0.813 | = 0.813 |

| Perceived Employability | = 0.732 | = 0.767 | = 0.799 | = 0.822 | = 0.822 |

| Social Consideration | = 0.751 | = 0.712 | = 0.701 | = 0.781 | = 0.841 |

| Vocational aspects | = 0.744 | = 0.773 | = 0.785 | = 0.715 | = 0.885 |

| Surrounding environment | = 0.721 | = 0.744 | = 0.729 | = 0.755 | = 0.895 |

| Geographic location | = 0.702 | = 0.788 | = 0.741 | = 0.787 | = 0.897 |

| Model | DF | Ratio | CFI | TLI | AIC | BIC | RSMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configurational Invariance | 1123.12 | 467 | 2.404 | 0.993 | 0.9901 | 0.02 () |

| Beginning of the Effect according to the Model | Previous year’s Enrollment | Seats Supply in the Previous Year | Seats Supply in the Year of Admission | Social Factors | Indivi- dual Factors | Perception of Supply / Demand in the Year of Admission | Correlation between Social and Individual Factors | Correlation between the Perceived Supply and the Demand in the 1st Option in the previous year with the Individual Factors | |

| End of the effect according to the model | Seats supply in the year of admission | 1st demand choice/ in the year of admission | |||||||

| (A) FOR A LARGE SIZE GENERAL UNIVERSITY | |||||||||

| Parameter (sample size) | |||||||||

| Areas | Social Sci (1289) | 0.388 | 0.879 | 0.775 | 0.621 | 0.704 | 0.443 | 0.377 | 0.412 |

| Experimental Sciences (1778) | 0.778 | 0.804 | 0.801 | 0.771 | 0.691 | 0.803 | 0.527 | 0.871 | |

| (B) FOR A SPECIALIZED UNIVERSITY OF AVERAGE SIZE | |||||||||

| Parameter (sample size) | |||||||||

| Areas | Social Science (215) | 0.321 | 0.441 | 0.328 | 0.402 | 0.621 | 0.714 | 0.443 | 0.329 |

| Experimental Sciences (204) | 0.221 | 0.277 | 0.216 | 0.344 | 0.651 | 0.543 | 0.612 | 0.881 | |

| Engineering (429) | 0.602 | 0.776 | 0.229 | 0.421 | 0.599 | 0.622 | 0.544 | 0.786 | |

| Arts (163) | 0.699 | 0.605 | 0.311 | 0.502 | 0.502 | 0.612 | 0.501 | 0.699 | |

| Health Science (184) | 0.601 | 0.599 | 0.433 | 0.592 | 0.613 | 0.677 | 0.487 | 0.745 | |

| (C) FOR A SPECIALIZED UNIVERSITY OF AVERAGE SIZE | |||||||||

| Parameter (sample size) | |||||||||

| Engineering | Agronomy(45) | 0.198 | 0.218 | 0.256 | 0.399 | 0.643 | 0.501 | 0.512 | 0.621 |

| Construction (82) | 0.335 | 0.321 | 0.299 | 0.441 | 0.678 | 0.592 | 0.571 | 0.699 | |

| ICT (102) | 0.644 | 0.612 | 0.618 | 0.649 | 0.612 | 0.676 | 0.623 | 0.679 | |

| Industrial (80) | 0.216 | 0.299 | 0.261 | 0.381 | 0.551 | 0.423 | 0.493 | 0.612 | |

| (D) FOR A SPECIALIZED UNIVERSITY OF AVERAGE SIZE | |||||||||

| Parameter (sample size) | |||||||||

| Degrees of Engineering | Industrial Electronics (123) | 0.541 | 0.676 | 0.229 | 0.221 | 0.399 | 0.555 | 0.321 | 0.551 |

| Industrial Chemistry (63) | 0.304 | 0.177 | 0.216 | 0.244 | 0.451 | 0.487 | 0.344 | 0.661 | |

| Mechanics (66) | 0.299 | 0.341 | 0.328 | 0.302 | 0.329 | 0.501 | 0.329 | 0.628 | |

| Electric (206) | 0.201 | 0.318 | 0.256 | 0.299 | 0.243 | 0.488 | 0.461 | 0.559 | |

| Industrial Design (82) | 0.289 | 0.421 | 0.299 | 0.341 | 0.578 | 0.522 | 0.422 | 0.712 | |

| Indices | Industrial Electronics | Industrial Chemistry | Mechanics | Electric | Industrial Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.921 | 0.943 | 0.899 | 0.900 | 0.877 |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | 0.925 | 0.944 | 0.887 | 0.901 | 0.878 |

| Bentler Bonnet Normed Fit Index (BBNFI) | 0.901 | 0.901 | 0.885 | 0.900 | 0.871 |

| Bentler Bonnet Non-Normed Fit Index (BBNNFI) | 0.902 | 0.903 | 0.884 | 0.902 | 0.873 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.899 | 0.899 | 0.891 | 0.899 | 0.878 |

| Coefficient of determination (R2) | 0.301 | 0.294 | 0.287 | 0.312 | 0.302 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Error (SRMSE) | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| with df = 240 | 554.11 | 734.12 | 612.88 | 594.23 | 643.28 |

| Ratio / df | 2.21 | 2.99 | 3.12 | 2.787 | 2.48 |

| Year | Effect on Demand | Factor | Effect SD | Demand Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Social Factors | 49.5 | ||

| n | Through Individual Factors | 20.3 | ||

| n | Through Individual Factors through Supply and Demand Perception | 15.5 |

| Year | Effect on Demand | Factor | Previous Year’s Demand | Cut-off Mark | Demand Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n+1 | Average grade of students entering universities | 319 | 9.90 | ||

| n+2 | Average grade of students entering universities | 227 | 8.86 | ||

| n+3 | Average grade of students entering universities | 180 | 8.42 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hervás, A.; Soriano, P.P.; Olmos, J.G.i.; Peró, M.; Capilla, R.; Montañana, J.M. Modelling the Process to Access the Spanish Public University System Based on Structural Equation Models. Math. Comput. Appl. 2020, 25, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca25020031

Hervás A, Soriano PP, Olmos JGi, Peró M, Capilla R, Montañana JM. Modelling the Process to Access the Spanish Public University System Based on Structural Equation Models. Mathematical and Computational Applications. 2020; 25(2):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca25020031

Chicago/Turabian StyleHervás, Antonio, Pedro Pablo Soriano, Joan Guàrdia i Olmos, Maribel Peró, Roberto Capilla, and José Miguel Montañana. 2020. "Modelling the Process to Access the Spanish Public University System Based on Structural Equation Models" Mathematical and Computational Applications 25, no. 2: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca25020031

APA StyleHervás, A., Soriano, P. P., Olmos, J. G. i., Peró, M., Capilla, R., & Montañana, J. M. (2020). Modelling the Process to Access the Spanish Public University System Based on Structural Equation Models. Mathematical and Computational Applications, 25(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca25020031