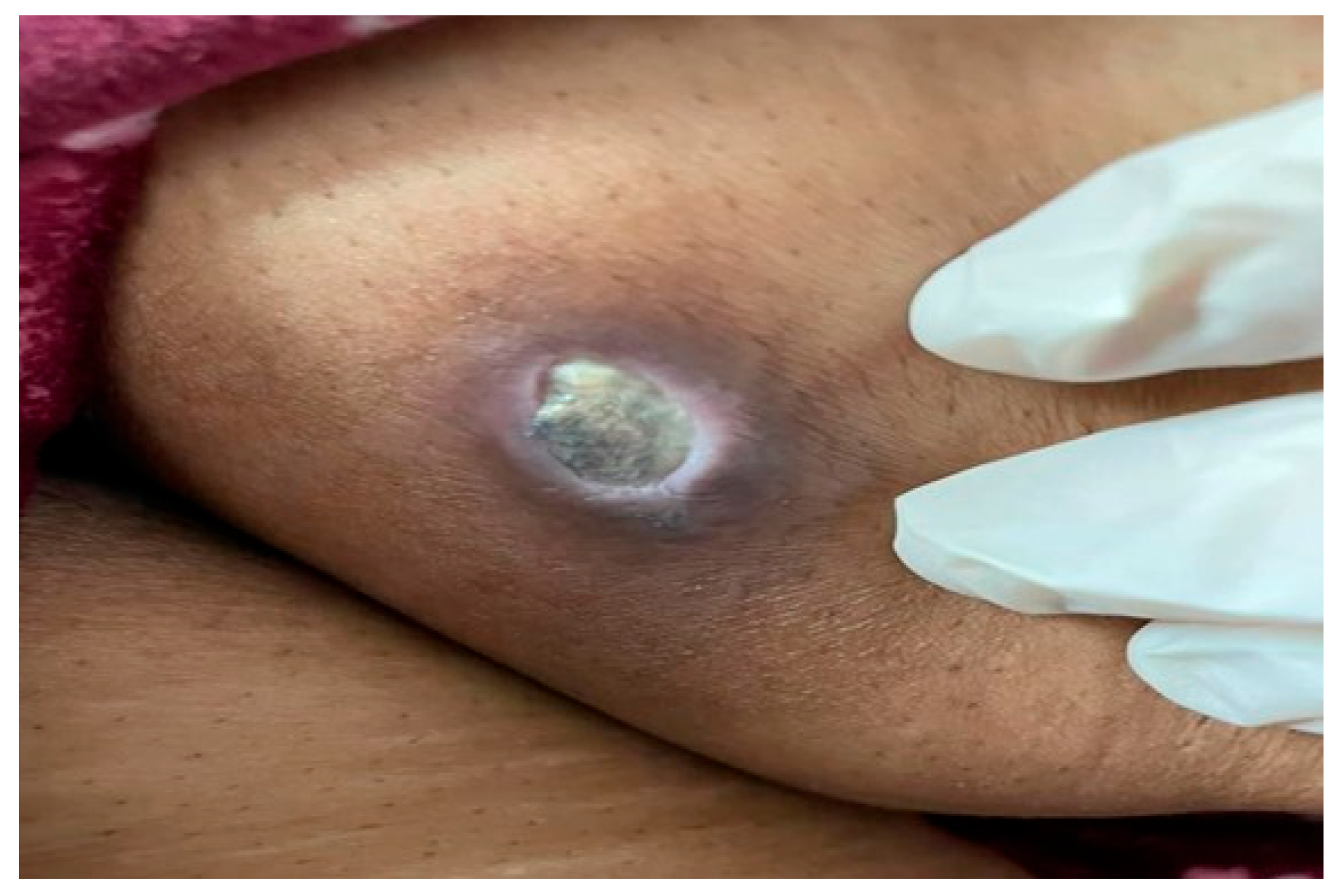

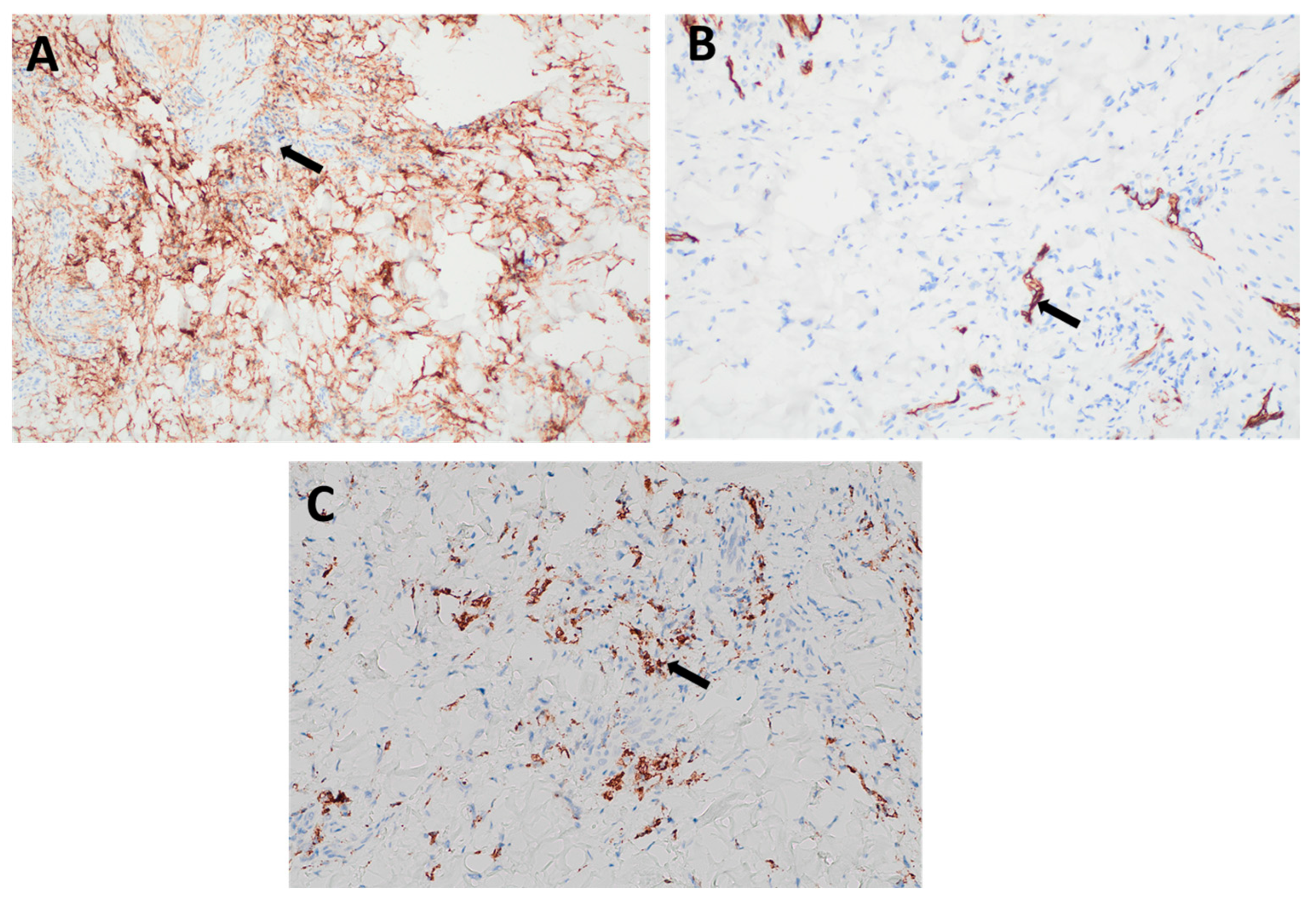

An Unusual Presentation of Dermatofibroma with Ulcer: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, S.; Wen, Z. A Clinical and Histopathological Analysis of 147 Cases of Dermatofibroma (Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma). Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.J.; Fillman, E.P. Dermatofibroma. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gershtenson, P.C.; Krunic, A.L.; Chen, H.M. Multiple clustered dermatofibroma: Case report and review of the literature. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2010, 37, e42–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Chang, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, W.M.; Son, S.J. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann. Dermatol. 2011, 23, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, M.R.; Besra, M.; Dutta, S.; Sarkar, S. Dermatofibroma: Atypical Presentations. Indian J. Dermatol. 2016, 61, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivala, A.; Lombardo, G.A.; Pompili, G.; Tarico, M.S.; Fraggetta, F.; Perrotta, R.E. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: Our experience of 59 cases. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khiewplueang, K.; Thanomkitti, K. Multiple Eruptive Dermatofibromas in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Lupus Nephritis and Receiving Immunosuppressive Drugs: A Case Report. Thai J. Dermatol. 2022, 38, 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, R.A.; Grant-Kels, J.M. 10—Benign brown-black and pigmented skin growths. In Dermatology for the Primary Care Provider; Waldman, R.A., Grant-Kels, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hueso, L.; Sanmartín, O.; Alfaro-Rubio, A.; Serra-Guillén, C.; Martorell, A.; Llombart, B.; Requena, C.; Nagore, E.; Botella-Estrada, R.; Guillén, C. Giant dermatofibroma: Case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007, 98, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Yus, E.; Soria, L.; de Eusebio, E.; Requena, L. Lichenoid, erosive and ulcerated dermatofibromas. Three additional clinico-pathologic variants. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2000, 27, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatrous, S.V.; Riahi, R.R.; Grisoli, S.B.; Cohen, P.R. Associated conditions in patients with multiple dermatofibromas: Case reports and literature review. Dermatol. Online J. 2017, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supsrisunjai, C.; Hsu, C.K.; Michael, M.; Duval, C.; Lee, J.Y.W.; Yang, H.S.; Huang, H.Y.; Chaikul, T.; Onoufriadis, A.; Steiner, R.A.; et al. Coagulation Factor XIII—A Subunit Missense Mutation in the Pathobiology of Autosomal Dominant Multiple Dermatofibromas. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 624–635.e627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilas, D.; García-Gavín, J.; Ginarte, M.; Rodríguez-Blanco, I.; Toribio, J. Ulcerated dermatofibroma with osteoclast-like giant cells. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36 (Suppl. 1), 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Vela, M.C.; Val-Bernal, J.F.; Martino, M.; Gonzalez-López, M.; García-Alberdi, E.; Hermana, S. Sclerotic fibroma-like dermatofibroma: An uncommon distinctive variant of dermatofibroma. Histol. Histopathol. 2005, 20, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlidag, T.; Keles, E.; Orhan, I.; Kaplama, M.E.; Cobanoglu, B. Giant ulcerative dermatofibroma. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2013, 2013, 254787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaimy, A. The many faces of Atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 40, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, O.A.; Dorobanțu, A.M.; Gurău, C.D.; Ali, S.; Mihai, M.M.; Popa, L.G.; Giurcăneanu, C.; Tudose, I.; Bălăceanu, B. Challenging patterns of atypical dermatofibromas and promising diagnostic tools for differential diagnosis of malignant lesions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelati, A.; Aqil, N.; Baybay, H.; Gallouj, S.; Mernissi, F.Z. Beyond classic dermoscopic patterns of dermatofibromas: A prospective research study. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuber, T.J. Punch biopsy of the skin. Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 65, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Sohn, K.; Kim, D.; Kim, B. Metastasizing dermatofibroma in lung. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2007, 11, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agero, A.L.C.; Taliercio, S.; Dusza, S.W.; Salaro, C.; Chu, P.; Marghoob, A.A. Conventional and Polarized Dermoscopy Features of Dermatofibroma. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.-H.; Huang, Q.; Yang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L.-J.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, R. Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of primary and recurrent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzis, D.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Veves, A. Pathogenesis and treatment of impaired wound healing in diabetes mellitus: New insights. Adv. Ther. 2014, 31, 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słonimska, P.; Sachadyn, P.; Zieliński, J.; Skrzypski, M.; Pikuła, M. Chemotherapy-mediated complications of wound healing: An understudied side effect. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Park, H.; Yoon, H.; Cho, S. A case of perforating dermatofibroma with floret-like giant cells. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 40, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Argenziano, G.; Buccini, P.; Cota, C.; Sperduti, I.; De Simone, P.; Eibenschutz, L.; Silipo, V.; Zalaudek, I.; Catricalà, C. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, P.; Duerden, B.; Armstrong, D.G. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, L. Diagnostic and therapeutic model of sepsis and purulent-Inflammatory diseases. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 10, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.S.; Foong, A.Y.; Koh, M.J. Ulcerated Giant Dermatofibroma following Routine Childhood Vaccination in a Young Boy. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2016, 8, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Vardareli, O.S.; Bilezikçi, B.; Ozgirgin, O.N. Dermatofibroma accompanied by perforating dermatosis in the auricle: A case report. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis. Derg. KBB J. Ear Nose Throat 2005, 15, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu, A.; Hsieh, A.; Kaya, G.; Menzinger, S. Perforating Fibrous Histiocytoma Mimicking Keratoacanthoma: A Case Report. Dermatopathology 2023, 11, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenoza, P.; Lillemoe, T. CD34 and factor XIIIa in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1993, 15, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F.; Improta, M.; Cicuttin, E.; Catena, F.; Sartelli, M.; Bova, R.; De’Angelis, N.; Gitto, S.; Tartaglia, D.; Cremonini, C.; et al. Surgical site infection prevention and management in immunocompromised patients: A systematic review of the literature. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.D.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, J.M.; Lee, E.S. Subcutaneous dermatofibroma. Ann. Dermatol. 2011, 23, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hao, X.; Billings, S.D.; Wu, F.; Stultz, T.W.; Procop, G.W.; Mirkin, G.; Vidimos, A.T. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: Update on the Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Trivedi, M.; Reid, D.C. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis after eyebrow wax burn. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 23, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.V.P.; Matos, D.M.; Barreiros, H.F.; Bártolo, E.A.F.L.F. Variants of dermatofibroma-a histopathological study. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Society of Dermatopathology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alakrash, L.; AlKanaan, R.; Aldihan, R.; Alsuhibani, A.; Almalki, S. An Unusual Presentation of Dermatofibroma with Ulcer: A Case Report. Dermatopathology 2025, 12, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12030028

Alakrash L, AlKanaan R, Aldihan R, Alsuhibani A, Almalki S. An Unusual Presentation of Dermatofibroma with Ulcer: A Case Report. Dermatopathology. 2025; 12(3):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlakrash, Lamia, Renad AlKanaan, Rema Aldihan, Alanoud Alsuhibani, and Salman Almalki. 2025. "An Unusual Presentation of Dermatofibroma with Ulcer: A Case Report" Dermatopathology 12, no. 3: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12030028

APA StyleAlakrash, L., AlKanaan, R., Aldihan, R., Alsuhibani, A., & Almalki, S. (2025). An Unusual Presentation of Dermatofibroma with Ulcer: A Case Report. Dermatopathology, 12(3), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12030028