Introduction

The parasitic infection of the eye caused by

Toxoplasma gondii, ocular toxoplasmosis, offers a wide variety of clinical presentations. It is one of the most common causes of posterior uveitis and focal posterior retinochoroiditis in immunocompetent patients [

1]. The involvement of the optic nerve is uncommon, and it is more often unilateral accounting for only 5.3% of cases [

2,

3,

4]. The presence of any degree of associated vitreous inflammation may corroborate this diagnosis, but a complete lack of vitreous inflammation at presentation should not exclude it [

5]. We report a case of presumed

Toxoplasma papillitis which developed without any vitritis both at presentation and during the follow-up period in an immunocompetent Congolese man.

Case report

A healthy 37-year-old man presented to the Department of Ophthalmology of the University Hospital of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, with a 1-month history of progressive painless severe loss of vision in his left eye. He had been initially unsuccessfully treated with systemic oral corticosteroids (betamethasone 8 mg daily for 1 week) with unclear suspicion of retrobulbar optic neuritis. Even though the patient is exposed daily to his pet cats, he did not have a known history of scratches from the cats. He also does not eat raw meat. He had no recent illness or other systemic complaints such as fever and/or lymphadenopathy and did not receive any medications. Thus, his medical, ocular, personal and family history was non-contributory to the diagnosis.

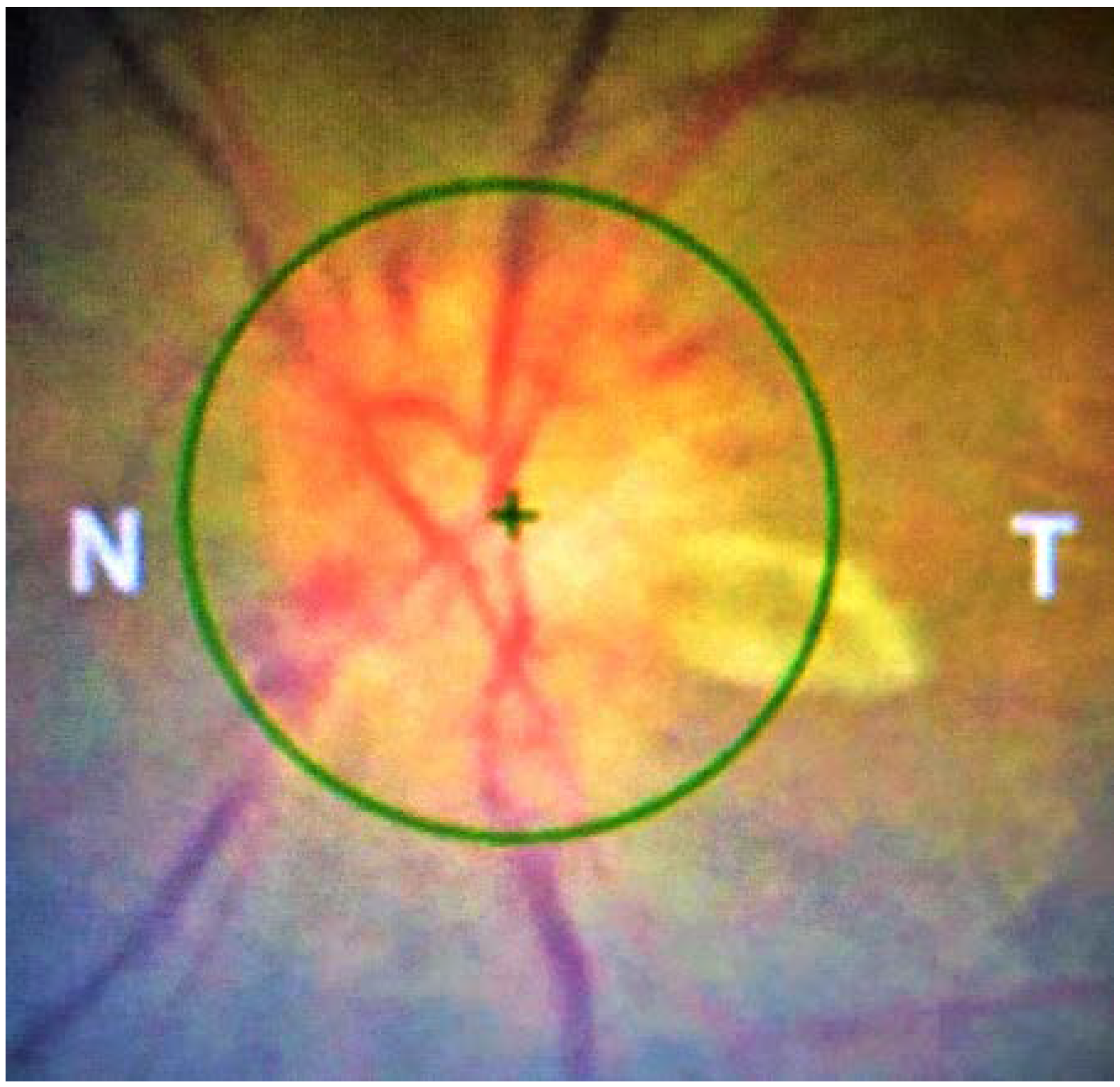

On ocular examination, visual acuity was 6/6 in the right eye and counting fingers (CF) in the left eye. A left relative afferent pupillary defect was present. External ocular examination, extraocular muscles movements and slit lamp examination (SL-3G Topcon Europe Medical, Capelle aan den Ijssel, The Netherlands) were normal in both eyes. Anterior chamber was free of any inflammatory cells. In Goldmann applanation tonometry, intraocular pressure was 15 mmHg in both eyes. Posterior segment examination excluded vitreous haze or cells in either eye. Dilated fundus examination with funduscopic biomicroscopy with Volk Super 66 stereo fundus lens revealed prominently swollen left optic disc with a focal whitish-yellow elevated fluffy area of retinochoroiditis on the temporal margin. There were also venous dilation, tiny splinter peripapillary radial hemorrhages, sheathing of adjacent peripapillary vessels and diffuse moderate edema of the peripapillary region (

Figure 1). Left macula and peripheral retina were normal. In addition, a paramacular inferior retinochoroiditis scar was observed in the right eye (

Figure 2).

Left eye computerized visual field examination (24-2 Sita Standard, Humphrey field analyzer MODEL 740i, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Dublin, CA, USA) revealed an enlarged blind spot, a dense altitudinal superior scotoma and a slight diffuse reduction of sensitivity in the inferior hemifield. Right visual field was normal (

Figure 3).

Ocular coherence tomography (Topcon 3D-2000, Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) of the left optic nerve head showed an importantly edematous optic nerve head associated with subretinal fluid around the optic disc and an important diffuse thickening of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (

Figure 4). OCT was normal in the right eye.

General and neurological examinations were normal. Laboratory investigations revealed normal full blood count, normal urea, creatinine, electrolytes and urine analysis as well as elevated CRP to 70 mg/L (normal levels <6 mg/L). Chest X-ray and orbito-cerebral magnetic resonance imaging were normal. Mantoux test for tuberculosis was negative. Anti-HIV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibodies and Western blot rapid test for HIV screening were negative. Serum anti-Toxoplasma ELISA antibody titer showed IgG positivity at 40 IU/mL (negative <4 IU/mL, suspected 4-7.9 IU/mL and positive >8 IU/mL according to the National Research Institute of Kinshasa) but negative IgM.

A presumed recurrent toxoplasmosis expressing as a papillitis with an active juxtapapillary retinochoroiditis focus in the affected eye and a healed retinochoroiditis in the unaffected eye, was strongly suspected in this patient.

Treatment

In the presence of clinical manifestations suggestive of papillary toxoplasmosis and positive IgG antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii, anti-toxoplasmosis medications were started orally. The treatment was initiated on day 3 post presentation and continued for six weeks with pyrimethamine 100 mg for the first day, then 50 mg daily, sulfadiazine 500 mg twice daily, spiramycin 3,000,000 IU twice daily, folinic acid 5 mg every two days. Due to the important papillary inflammation, the patient simultaneously received a periocular injection of triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg/1 mL). We introduced prednisone orally on day 2 after start of anti-toxoplasmosis medications with a dose of 40 mg daily for one week and then tapered to 10 mg daily until the end of the treatment. Absence of vitritis in the left eye was checked again, before starting treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

Clinical improvement was noticed two weeks following treatment. Visual acuity increased from counting fingers to 6/24 in the left eye. Left optic disc edema and hyperemia drastically decreased together with a marked reduction of the juxtapapillary retinochoroiditis. Reduction of disc edema and subretinal fluid was concomitantly well documented in OCT (

Figure 5A).

Six weeks after treatment, visual acuity reached 6/6 in the left eye. In fundus examination, left optic disc edema had disappeared, whereas the juxtapapillary active lesion resolved without any retinochoroiditis pigmented scar (

Figure 5B). CRP was normalized to 0.53 mg/L, whereas anti-

Toxoplasma IgG were stable to 39 IU/mL after the end of anti-toxoplasmosis treatment.

Eighteen months after cessation of treatment, the patient’s visual acuity was 6/6 in both eyes. Left eye anterior and posterior segments were free of inflammation. In ophthalmoscopy, the left optic disc was diffusely extremely pale and atrophic. No retinochoroiditis pigmented scar was visible. Visual field showed an absolute central scotoma and a slightly increased defect in the superior hemifield. Examination of the right eye was unchanged. CRP was normal; anti-Toxolpasma IgG was still positive at 32 IU/mL with negative IgM.

Complete resolution of the retinitis with a pigmented scar.

The macular star resolved with retinal pigment epithelial changes.

Discussion

The overall burden of neglected tropical diseases such as toxoplasmosis was reported to be greatly underestimated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where the seroprevalence for toxoplasmosis in a series of 310 persons in the city of Pointe-Noire was found to reach 42% and affect predominantly people under 20 years of age [

6,

7].

Figure 6.

(A) Eighteen months post treatment, fundus photography of the left optic disc showed severe diffuse pallor, absence of any retinochoroiditis pigmented scar. (Presence of an artefact in the superotemporal peripapillary region). (B) and (C) Left eye control OCT examination showing diffuse loss of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer as well as complete resolution of thickening of the optic nerve head. (D) Left eye visual field control examination in automated perimetry showing the presence of a slightly increased defect in the superior hemifield associated with an absolute temporal central scotoma.

Figure 6.

(A) Eighteen months post treatment, fundus photography of the left optic disc showed severe diffuse pallor, absence of any retinochoroiditis pigmented scar. (Presence of an artefact in the superotemporal peripapillary region). (B) and (C) Left eye control OCT examination showing diffuse loss of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer as well as complete resolution of thickening of the optic nerve head. (D) Left eye visual field control examination in automated perimetry showing the presence of a slightly increased defect in the superior hemifield associated with an absolute temporal central scotoma.

Our case reported clinically at the fundus presentation a severe optic disc edema and a juxtapapillary active focus of retinochoroiditis, being strongly suggestive of toxoplasmic anterior optic neuropathy (TAON) type I.

Ocular toxoplasmosis with direct optic nerve head involvement due to neuritis or neuroretinitis had also been designated as toxoplasmic anterior optic neuropathy (TAON) by Banta JT and colleagues [

8]. In their work, they distinguished two different types, I and II, based on clinical findings and course of the disease. Type I was described as a secondary infectious involvement of the optic nerve head from an adjacent focus of retinochoroiditis associated with overlying posterior vitreous inflammatory reaction and resolving with retinochoroiditis scarring. The Type II on the other hand represents a primary isolated involvement of the optic nerve head with frequent spread into the surrounding retina, inflammatory cells and debris in the posterior vitreous but without adjacent focus of retinochoroiditis at onset. It had also been suggested that type I could be an important inflammatory reaction in response to mediators released from near-inflammation by the presence of parasite directly in the optic nerve [

2]. In both types, visual prognosis was generally favorable unless the macula was involved.

Arcuate, altitudinal, or central visual field permanent scotomas indicative of papillary involvement had persisted in our patient after treatment [

8,

9]. The post-treatment persistence of these scotomas is thought to be due to remaining full-thickness optic disc atrophy despite the resolution of the active lesion [

9].

A relative afferent pupillary defect, which was also highlighted in our patient, supported the diagnosis [

5]. Moreover similarly in our patient, a paramacular inferior retinochoroiditis scar in the unaffected eye was suggestive of recurrent toxoplasmosis in the affected eye. In the study by Eckert et al. 55% of patients who had presented toxoplasmic optic nerve damage had pre-existing lesions retinochoroidal scars or at the optic disc in the affected eye [

2].

One of the most indicative findings of active toxoplasmosis is vitritis. In our case, we observed absence of vitritis at presentation and after treatment. Some authors have reported the absence of vitreous inflammation at presentation [

2,

5,

8]. However, the absence of any vitreous inflammation at presentation as well as afterwards is somewhat quite atypical and remains unexplained. Among possible hypotheses, we can suppose that it may be due to the corticosteroid treatment that the patient received before he had consulted in our Department.

Lee et al., in their study, found that the toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients was reported to possibly develop without vitritis but the disease was multifocal and had a high incidence of toxoplasmosis encephalitis [

10]. In our patient who was otherwise in good general health, only immunodeficiency due to HIV infection could be excluded by serology. Serum anti-

Toxoplasma gondii IgG was positive indicating, in the absence of IgM, the systemic recurrent invasion which happened before [

11]. Importantly the presence of a retinochoroiditis scar in our patient’s heterolateral eye was very suggestive of prior ocular toxoplasmosis infection and was supported by serologic tests.

Finally, no retinochoroiditis pigmented scar was detected in the left eye eighteen months after treatment. We could hypothesize that the patient’s retinal pigment epithelium was not significantly damaged during the active stage of the disease [

12].

The diagnosis of our case was primarily based on his clinical features but imperatively differentiated from other causes of optic disc swelling with perichorioretinal extension such as bartonellosis, sarcoidosis, leptospirosis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The small number of serologic tests that could be performed in our case report represents a major limitation. Given the cost implications of related biological investigations such as serology for syphilis, Lyme borreliosis, cat scratch disease, toxocariasis, cytomegalovirus, retrovirus, herpes simplex and zoster virus and rubella, these were not initially analyzed in the clinical context of our patient. Similarly, rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies and anti-Brucella antibodies were not investigated in the absence of indicative clinical signs in our patient. The failure to perform the VDRL and ELISA test for cat scratch disease meant that these diseases could not be correctly ruled out, although with the presence of typical toxoplasmic scars in the other eye, these two etiologies were less likely than toxoplasmosis.

Little is still known about the frequency of Lyme disease in Congo, but this etiology could be a priori excluded in our patient in the absence of systemic associated symptoms and signs in favor of borreliosis.

Conclusions

We report a case of presumed recurrent acquired ocular toxoplasmosis responsible for unilateral papillitis associated with juxtapapillary active retinochoroiditis focus in the absence of vitritis both at presentation and during follow-up. The unilateral inflammation in the optic nerve head and peripapillary area coexisting with active juxtapapillary retinitis, the presence of a retinochoroiditis scar in the other eye, the positive Toxoplasma titers, the favorable response to appropriate anti-parasitic agents were highly suggestive for toxoplasmic anterior optic neuropathy.

Our patient’s clinical presentation suggests that such a diagnosis should be suspected even in the complete absence of vitreous inflammation during the active phase of the disease. The clinician should be aware of the rareness, the potential severity of the disease without treatment and the differential diagnostic difficulties with other types of neuritis and swollen optic disc.

Finally, our case report highlights the major importance of a detailed and exhaustive patient’s history and extensive clinical examination to enable informed decision making on the need for complementary investigations, especially for serologic tests, in a country with relatively limited financial resources in public healthcare.