Case report

A 69-year-old man presented in November 2018 with a 3-day history of cough and fever. He reported significant tobacco consumption, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treated with successive tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors since 2004. His immunosuppressive therapy had been strengthened with high-dose corticosteroids in August 2018 because the RA had relapsed, and etanercept had just been replaced by abatacept (an inhibitor of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 receptors) few days prior to admission. The first evaluation revealed: temperature of 37.9 °C, blood pressure of 126/69 mmHg, respiratory rate of 32/min, and oxygen saturation of 95% on 3L/min of O

2. He was alert but complained of cough and dyspnea. The chest examination mainly revealed crackles in the right field. Initial lab work showed: hemoglobin 12.8 g/dL, WBC count 9,600 /µL, platelet count 178,000 /µL, creatinine level 22.3 mg/L, C-reactive protein 514 mg/L, and procalcitonin 4.9 ng/mL. On room air arterial blood gas showed pH of 7.50, O

2 pressure of 53 mmHg, and CO

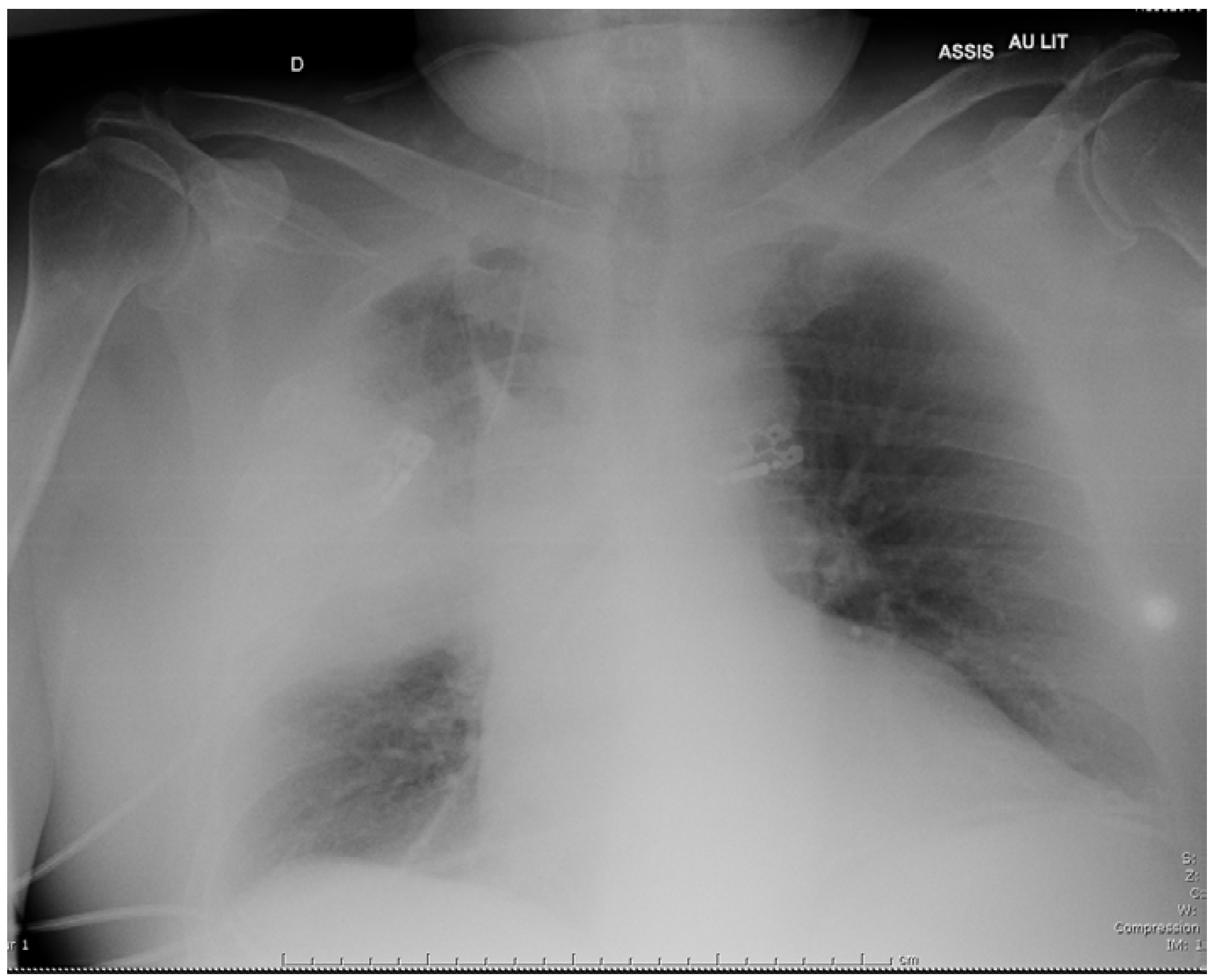

2 pressure of 34 mmHg. Chest X-ray demonstrated alveolar infiltrates in the middle part of the right lung (

Figure 1). The patient received intravenous (i.v.) cefotaxime, 2 g every 8 h, plus i.v. levofloxacin, 500 mg daily, as empirical therapy, then was admitted to the intensive care unit because he required non-invasive ventilation.

All the first microbiological tests were negative (blood cultures, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 and Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary antigen tests (UAT) (BinaxNow®, Alere, Waltham, MA, USA), Pneumocystis DNA PCR in sputum, test for influenza A and B in nasopharyngeal aspirates, HIV serology). No pathogenic bacteria were grown on sputum cultures plated onto standard Columbia blood agar, chocolate agar, Drigalski and Sabouraud plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA, and BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France).

On the sixth day bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid only grew Candida albicans, and specific quantitative herpes simplex virus-1 PCR was weakly positive. Considering that colonization of the airways by Candida and herpes simplex virus could worsen respiratory parameters, we added i.v. fluconazole 400 mg daily, and acyclovir 600 mg every 8 h, to the antibiotics. Otherwise specific mycobacteria cultures and serologies for Coxiella burnetii, Aspergillus, and L. pneumophila remained negative.

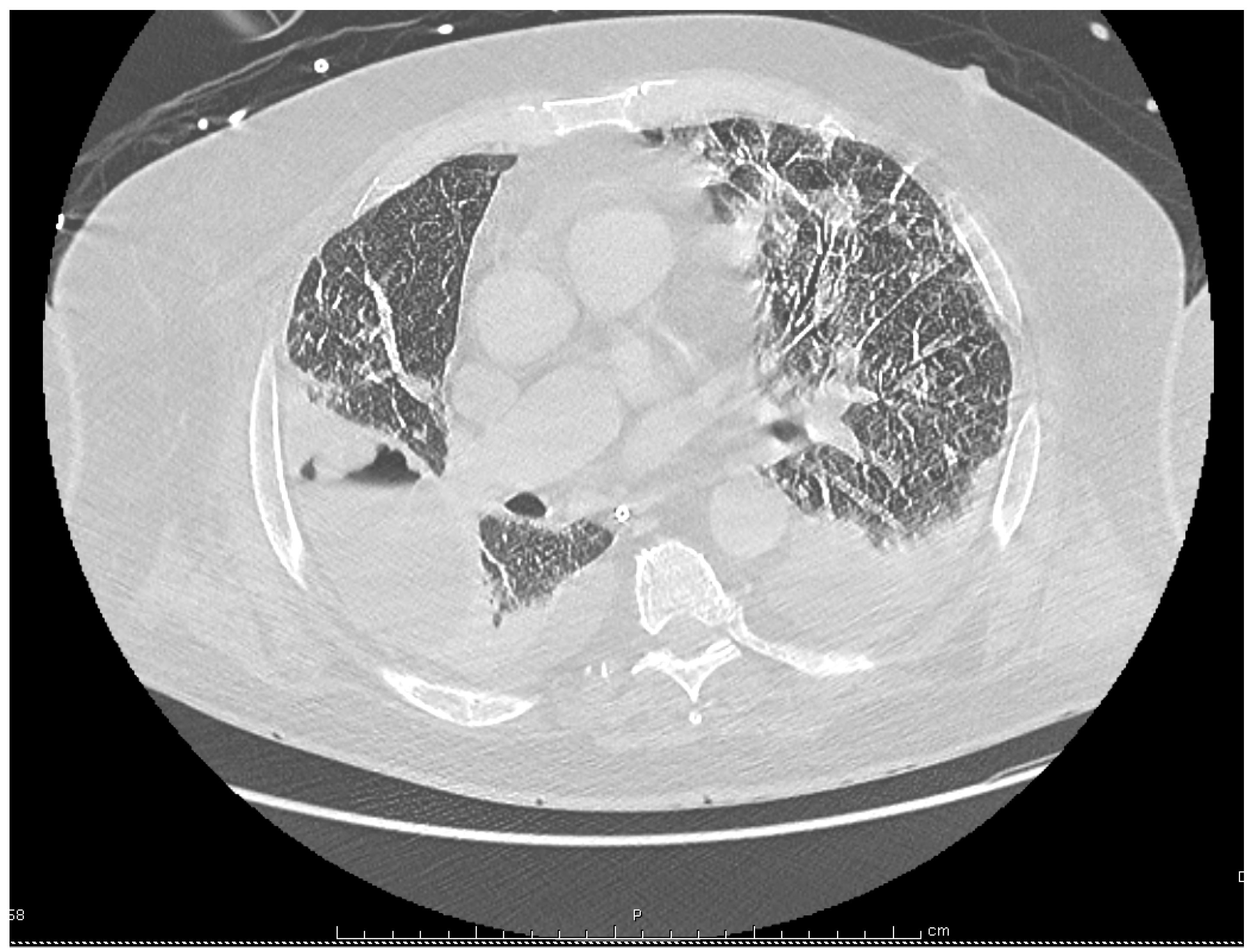

Despite these treatments the patient’s condition deteriorated with the onset of respiratory failure and septic shock, requiring the use of vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation. Antimicrobial coverage was therefore broadened with the replacement of cefotaxime and levofloxacin by i.v. meropenem, 2 g every 8 h, and i.v. linezolid 600 mg twice a day, although no pathogenic bacteria had been identified yet. A chest computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral pleural effusions, patchy alveolar infiltrates, and a large abscess in the right lobe measuring 85 by 57 by 53 mm (

Figure 2). Intravenous voriconazole 400 mg every 12 h, was thus substituted for fluconazole with concern for an

Aspergillus infection, and acyclovir was discontinued.

The three following weeks were marked by an unfavorable evolution, with recurrent hemodynamic and renal failures despite the adjunction of intravenous metronidazole 500 mg every 8 h, and colistin 3 million international units (MIU) every 8 h. Hemodialysis was started, and a second BAL was performed but the conventional cultures yielded negative results again. At that time drainage of the abscess seemed to be the best way to identify the causal agent, but it couldn’t be performed easily because of high risks of bronchopulmonary fistula. CT was repeated twice and showed no improvement under empirical therapy, but a large pleural empyema had appeared on the last exam. This allowed a safer drainage of the pleural collection on day 34, and the removal of 150 mL of purulent liquid rich in polymorphonuclear cells. Abscess cultures only grew fluconazole-sensitive

Candida albicans. Finally, 16S rRNA PCR came back positive one week later, with sequences homologous to

L. micdadei [

8]. Samples were sent to a reference laboratory for

Legionella, and

L. micdadei could be grown on

Legionella-specific buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar, on BCYE supplemented with glycine (3 g/L), vancomycin (1 mg/L), polymyxin B (50,000 UI/L) and anisomycin (80 mg/L) called MWY medium, and on BCYE supplemented with cefamandole (4 mg/L), polymyxin B (80,000 UI/L) and anisomycin (80 mg/L) called BMPA medium. The results were confirmed by sequencing of the

mip- (macrophage infectivity potentiator) gene from

L. micdadei cultures, then by comparison with the GenBank database.

We thus decided to withdraw broad-spectrum antibiotics, and to introduce an additional 3-week course of i.v. levofloxacin 500 mg every 12 h, plus i.v. spiramycin 3 MIU every 8 h, which led to transient improvement of respiratory and hemodynamic parameters. Unfortunately, his condition gradually deteriorated again at the end of the treatment, because of catheter-related bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus epidermidis, then nosocomial pneumonia due to

Morganella morganii.

L. micdadei DNA was still isolated on the two last BALs, using specific

Legionella PCR (kit Diagenode

®, Diagenode s.a., Liège, Belgium) and sequencing of the 23S-5S ribosomal intergenic spacer region [

9], but

Legionella specific cultures remained negative. Despite the reintroduction of vancomycin, loading dose followed by continuous perfusion of 30 mg/kg each day, then i.v. cefepime 2 g every 8 h, and i.v. levofloxacin, 500 mg every 12 h, the patient died three months after his admission.

Discussion

Our case underlines some of the pitfalls in diagnosing

L. micdadei infections.

L. micdadei are ubiquitous bacteria responsible for pneumonias that preferentially affect profoundly immunosuppressed people, as was our patient under immunosuppressive medications and more recently added high-dose corticosteroids [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The reasons why

L. micdadei are rarely found in healthy people are not clear. Even if

L. micdadei and

L. pneumophila share virulence genes, it seems that

L. micdadei are less virulent than

L. pneumophila, and show fewer cytotoxic capacities when cultured with macrophages [

10].

Our patient suffered from a severe legionellosis for which the diagnosis has been challenging and delayed. At first, initial empirical treatment including levofloxacin to cover a putative legionellosis was ineffective. Moreover, the negative urinary antigen results and the occurrence of a cavitation misled us, and prompted us to look for differential diagnoses, such as more frequent opportunistic infections. Therefore, we withdrew levofloxacin on the tenth day. Legionellosis is commonly described as alveolar or interstitial pneumonia. However it is worth noting that several previously reported cases of

L. micdadei infections in immunocompromised individuals have become complicated by lung abscess [

1,

5,

6,

7]. Even though

L. micdadei are responsible only for a low percentage of legionellosis cases, we believe it is important for clinicians to be aware of

L. micdadei’s propensity to induce pulmonary nodules that can cavitate in this high-risk population.

Legionella are fastidious, facultative intracellular bacteria, difficult to isolate in the laboratory. When stained in tissue samples they may appear as weakly acid-fast bacilli, which may induce a misdiagnosis with tuberculosis [

4]. Their isolation requires BCYE or BCYE-derived media, but these aren’t routinely used. Moreover, non-

pneumophila Legionella are more fastidious in cultures than

L. pneumophila, which may further induce false-negative results [

2,

11]. UAT partially help overcome these difficulties, but they only reliably detect

L. pneumophila serogroup 1 infections, with a low sensitivity for the other species or serogroups. As a consequence, for people at risk of non-

pneumophila Legionella infections, clinicians should not rely exclusively on urinary assays to rule out a diagnosis of legionellosis.

In our case, delay in diagnosis was also due to the location of the abscess that prevented collection of appropriate samples because of risks of bronchopleural fistula. The drainage could only be performed after a pleural empyema had appeared. 16S rRNA PCR, 23S-5S rRNA PCR, sequencing of the mip-gene, and cultures of these samples on BCYE agar allowed the identification of L. micdadei. Drug-susceptibility testing demonstrated that levofloxacin and spiramycin were effective on this strain. Therefore, they were chosen to treat our patient for three additional weeks according to national guidelines. This treatment showed efficacy since we observed clinical improvement and the last BAL cultures had become negative, but the patient underwent complications of such a prolonged hospitalization, and died one month after completion of this treatment.

During legionellosis bacteria replicate efficiently within alveolar macrophages, but the natural reservoir of

Legionella are freshwater environments, where they live in biofilms and sediments and replicate within free-living amoebae [

3]. These protozoa can withstand extreme environments, which protects

Legionella against disinfection of water distribution systems. Legionellosis are hospital- or community-acquired, transmitted through inhalation of contaminated aerosols or droplets from water supplies, aerosol-generating devices, cooling towers, air conditioners, spas, etc. The link between such exposures and the risk of legionellosis is well known for

L. pneumophila [

12], but

L. micdadei share the same environmental niche [

3]. Our patient denied having recently used air conditioner or spa, but he was suffering from OSA and needed continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night. When such therapy is initiated advice about the daily cleaning of the mask and tubing are given. They must be correctly and regularly performed to avoid the colonization by waterborne bacteria such as

Legionella. Guidelines recommend the use of sterile, distilled, or cooled boiled water to rinse or fill the CPAP components, since it has been demonstrated that they could become a secondary reservoir for

Legionella if inappropriate cleaning was performed [

12]. Here we were unable to determine the source of this infection, but we strongly suspected the CPAP devices to be colonized by

L. micdadei, after the patient’s wife told us that they regularly rinse the equipment with tap water. This community-acquired infection was notified to the Health Regional Agency, but no investigation was performed at the patient’s home, since no outbreak had occurred.