Abstract

Introduction: Febrile neutropenia is one of the most serious treatment-related complications in cancer patients. Susceptible to rapidly progressing infections, which result in prolonged hospitalization and use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, neutropenic patients are subject to colonization by multiresistant agents, which enhances the risk of infections. Methods: In this study we included samples collected with nasal, oropharyngeal and anal swabs from hospitalized children with febrile neutropenia following chemotherapy, between March 2014 and 2015, aiming to elucidate colonization by S. aureus and Enterococcus spp., as well as their resistance profile. Results: S. aureus was found in 22% of the patients and 14% of the events. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus colonized 13.6% of patients. Including anal swabs in the screening increased the identification of colonized patients by 20%. Enterococcus spp. was found in 27% of patients and 17% of episodes. Enterococcal isolates resistant to vancomycin, accounting for 25% of the total, were not isolated in anal swabs at any time, with the oropharyngeal site being much more important. The rate of infection by Enterococcus spp. was 4.5% of all patients and 16% among the colonized patients. Conclusions: Especially in this population, colonization studies including more sites can yield a higher chance of positive results. Establishing the colonization profile in febrile neutropenic children following chemotherapy may help to institute an empirical antibiotic treatment aimed at antibiotic adequacy and lower induction of resistance, thereby decreasing the risk of an unfavorable clinical outcome.

Introduction

Febrile neutropenic patients are often immunosuppressed, frequent users of health services, undergoing broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, susceptible to rapidly progressing infections and sometimes to prolonged hospitalization. They also have risk factors for changes in their microbiome, with consequent colonization by multiresistant agents [1,2,3,4]. In addition to the skin and respiratory tract, the gastrointestinal tract is a major source, with both its colonization by resistant agents and the loss of its mucosal integrity caused by the direct action of chemotherapy, being conditions for bacterial translocation and systemic dissemination [5,6].

The colonization by resistant agents enhances the risk for infection, which can be 38 times higher than that observed in non-colonized patients [3,4]. In immunocompromised patients, it is estimated that 30% of those who have been colonized will develop bacteremia, whereas in pediatric oncological patients, this rate can range from 5% to 50%. Noteworthy is also the fact that colonized patients are potential sources of in-hospital transmission [7,8].

A survey on febrile neutropenic children following chemotherapy conducted in our service showed Gram-negative bacteria representing 42% and Gram-positive 48% of all blood cultures isolates. This distribution with a discrete predominance of Gram-positive bacteria could also be seen in oncological children in a Chilean series where 42% were Gram-negative and 55% were Gram-positive in 2010, a fact that was observed to be more pronounced in Ronsenblum’s series from 2012 in adults with cancer, where 70% of the isolated agents were Gram-positive [9,10,11].

The previous isolation of a resistant agent or even colonization by it, especially by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), in a cancer patient should alert the physician to change the initial antibiotic regimen in episodes of febrile neutropenia, considering the early association of vancomycin, linezolid or daptomycin as indicated by the main guidelines for handling this infectious emergency [12].

Thus, colonization studies are deemed important not only because they demonstrate the predisposition towards developing invasive infections in colonized patients, but also because they show how the monitoring of colonization and the pressure thereby exerted can serve as a strategy to institute infection control measures [13]. Furthermore, antibiotic resistance has been a threat to the successful treatment of infections, and understanding colonization can direct the empirical treatment given to febrile neutropenic patients, aiming to achieve better therapeutic success, thus decreasing the chances of an occasional unfavorable outcome [4,5,14].

The aim of this study was to elucidate the rate of colonization by S. aureus and Enterococcus spp., as well as their resistance profile in febrile neutropenic patients following chemotherapy.

Methods

Oncological children with neutropenic fever secondary to chemotherapy and hospitalized at the Pediatric Department between March 2014 and March 2015 were included in the study. By definition, fever was adopted as being: axillary temperature equal to or higher than 37.8 °C, recorded at the time of admission or reported by the responsible caregiver. Neutropenia, in turn, was defined as total neutrophil count lower than 500 cells/cmm or lower than 1000 cells/cmm with falling trends. Patients who experienced neutropenia secondary to any other condition than chemotherapy side effects and/or patients who started fever and neutropenia during hospitalization were excluded from the study.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (CEP 016/14/Caae 2306931400005479), and all legal guardians of the children included in the study had access to explanations of the consent form prior to signing it; teenagers had access to and signed the consent term.

Upon arrival at the service, or within 48 hours after admission, patients underwent sample collection through anal, nasal and oropharyngeal swabs. If hospitalization exceeded seven days, the patients underwent new collection every seven days.

The samples were plated on blood agar, mannitol agar (Probac do Brazil, São Paulo, Brazil) and chromogenic media (CHOMagar MRSA and VREBAC-Probac do Brazil, São Paulo, Brazil). Bacterial identification was based on Gram stain and traditional biochemical methods. The susceptibility test was performed with the disk diffusion method by employing the recommended methodology and interpretation guidelines as set out by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [15]. S. aureus isolates resistant to three or fewer classes of antimicrobials were considered phenotypically from a microbiological point of view as community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). As all patients had history of contact with health services, all isolates were considered health-care associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) from an epidemiological point of view.

Results

We evaluated 35 episodes of febrile neutropenia in 22 different cancer patients (14 females and eight males). Of the 35 episodes, 46% corresponded to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 6% to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 17% to lymphomas, and 14% to solid tumors. The patients’ mean age was 7.5 years, with a standard deviation of 3.84 and a median of 6.0.

Among the episodes, 10 had an established source of infection upon admission: mucositis, stomatitis, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and one corresponded to a peripherally inserted central catheter infection. In the remaining 74%, there was no identifiable focus of infection. In all of the episodes, the patients received initial antibiotic therapy according to the already established protocol in place with the service, which consists of cefepime or piperacillin-tazobactam monotherapy, or in association with vancomycin in cases of catheter-related infection, severe mucositis, skin and soft tissue infection or hemodynamic instability.

In 85% of the cases, the episode of febrile neutropenia was preceded by hospitalization in the previous month.

With respect to sample collection, a total of 121 swabs were analyzed: 40 anal swabs, 41 nasal swabs, and 40 oropharyngeal swabs. Of the 121 swabs, no agent whatsoever was isolated in 35 of them, and among 66, one Gram-positive was isolated, with 100% of patients having had at least 1 site colonized by Gram-positive bacteria. Such positive samples were distributed as follows: 15 tested positive for Streptococcus viridans, 23 for coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, 10 for Staphylococcus aureus, and 18 for Enterococcus spp.

S. aureus was found in 5 different patients. Thus, the colonization by this agent was present in 22% of patients and 14% of episodes.

In regard to the clinical characteristics of colonized patients, all but one had been admitted to hospital in the previous month, and in none of them a source of infection was known at the time of admission; the mean hospital length of stay was 12.6 days and 40% of them had more than one episode of febrile neutropenia over the duration of the study. Only one of the colonized patients had an indwelling catheter, with an operating time of 180 days. None of the patients had an unfavorable clinical outcome.

Of the two colonized patients who experienced more than one episode of neutropenia over the duration of the study, one was already colonized in the first episode, but had negative swabs in the beginning of the second episode, which happened within an interval of eight months. The other one, in turn, tested negative at the time of the first episode, but had positive anal and oropharyngeal swabs when investigated at the time of the second episode, with the episodes having occurred four months apart.

The samples that tested positive for S. aureus were four anal swabs, four nasal swabs, and two oropharyngeal swabs, which corresponded to 10% positivity among anal swabs, 9.7% among nasal swabs, and 5% among oral swabs.

Only two of the colonized patients presented with the isolated agent in one single site studied, namely the nasal site. In the remaining patients, S. aureus was isolated in more than one site as early as the time of admission: one tested positive in both the anal and the oropharyngeal swabs; one in the anal and nasal swabs; and one in all of the swabs, anal, nasal and oropharyngeal. This patient with an agent isolated from three sites underwent recollection after seven days within admission to hospital, with the anal swab remaining positive for S. aureus.

None of the isolates showed resistance to vancomycin, but 80% of them were resistant to oxacillin.

In the patient who had S. aureus isolated from all three sites, the agent showed similar resistance profiles in the three samples, all of which were found to be multiresistant. This same patient tested positive for the agent upon anal swab recollection on the seventh day of hospitalization, and S. aureus isolated from this sample had the same antimicrobial susceptibility profile.

Similarities in the microbiological profile were also seen in patients with S. aureus in their anal and nasal swabs, once again found to be multiresistant.

Finally, the two isolates from the oropharyngeal and anal swabs from the same patient showed a profile characteristic of CA-MRSA, resistant only to penicillin, oxacillin and erythromycin. The nasal site in this patient was colonized and both isolates were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

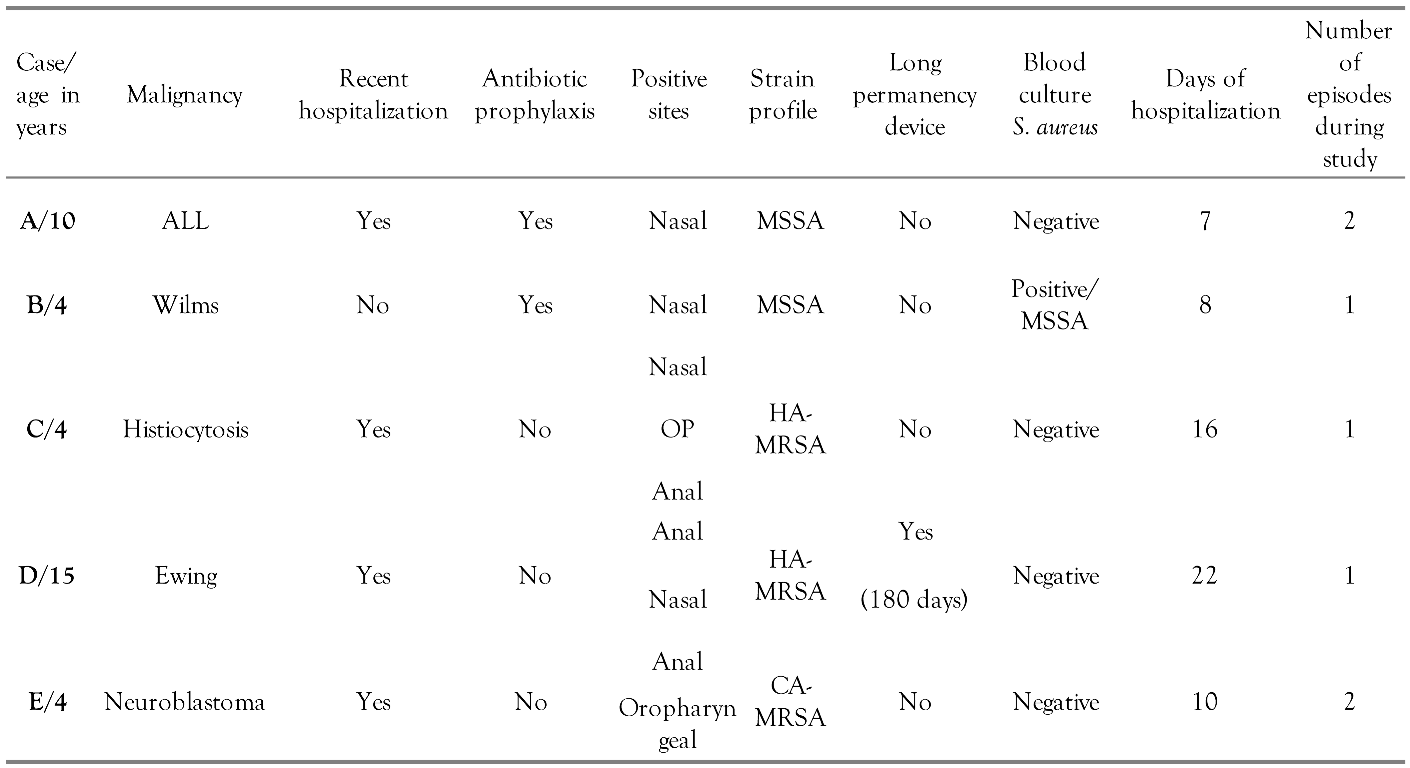

The clinical characteristics of the colonized patients, as well as the sites that tested positive, are described in Table 1. Table 2 gathers antimicrobial susceptibility of S. aureus isolated from each site and patient.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, positive sites, and resistance profile of the strains isolated from patients colonized by S. aureus.

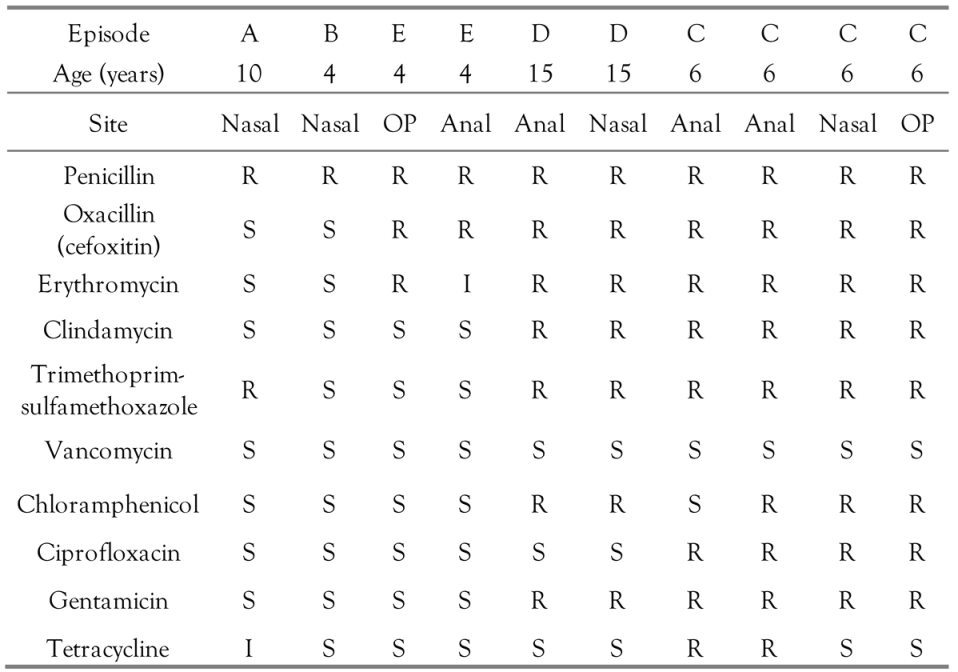

Table 2.

Antibiogram for S. aureus isolates from each site and by patient.

Enterococcus spp. was found in six different patients. Thus, the colonization by this agent was present in 27% of patients and 17% of episodes.

With respect to the clinical characteristics of the patients colonized by Enterococcus spp., over half of them had been admitted to hospital in the same month when the episode of neutropenia was studied, and only one presented with a possible source of infection upon admission, namely mucositis. The mean hospital length of stay for colonized patients was 14 days, all of them except one made use of vancomycin during hospitalization and required a subsequent anti-fungal association in addition to the initial antibiotic regimen due to persistent fever. None of the colonized patients progressed to death during the period of time that the episodes were followed up.

The samples that tested positive for Enterococcus spp. were distributed among six anal swabs, four nasal swabs, and eight oropharyngeal swabs, which corresponded to 15% positivity among anal swabs, 9.7% among nasal swabs, and 20% among oral swabs.

In analyzing the positive sites identified in the colonized patients, two patients had isolated samples only from anal swabs, one patient had positive oropharyngeal and nasal swabs, one patient had positive anal and nasal swabs, and two patients had agents isolated from oropharyngeal, nasal and anal swabs.

In addition to Enterococcus spp., S. aureus was isolated concurrently in two patients: in the first patient, both agents from the oropharyngeal site, whereas in the second patient, both from the anal site.

The infection rate in colonized patients was 16%. Enterococcus spp. was isolated in urine culture of one of the colonized patients, and it was a vancomycin-susceptible isolate. This same patient was also the only one who had an indwelling catheter at the time of inclusion, with a 180-day operating time, and developed severe sepsis, requiring ICU admission and orotracheal intubation.

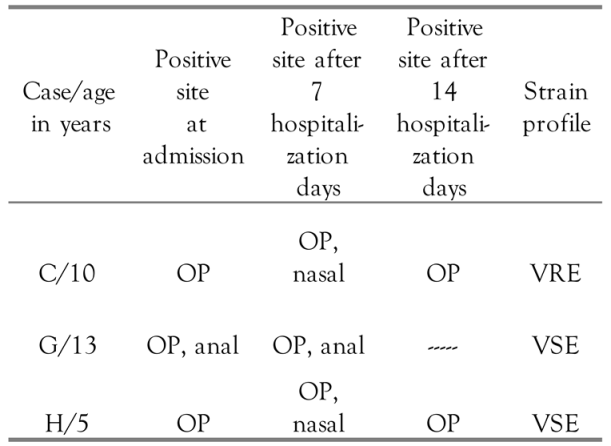

The clinical characteristics of patients colonized by Enterococcus spp., as well as the distribution of sites that tested positive, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients colonized by Enterococcus spp.

Half of the colonized patients underwent recollection after seven days of hospitalization in compliance to the study protocol.

In analyzing the patients who underwent recollection, only one had a positive site at the time of the first collection, having progressed to positivity in all three sites on the fourteenth day of hospitalization. All patients with positive oropharyngeal swabs at the time of the first evaluation tested positive for that site again when they underwent subsequent recollections. Only one patient was excluded from the protocol, which occurred after the second recollection. The number of positive samples according to the days of hospitalization is showed in Table 4, which demonstrates the persistence of positive results for oropharyngeal swabs in all recollected samples.

Table 4.

Evolution at recollection by site and resistance profile.

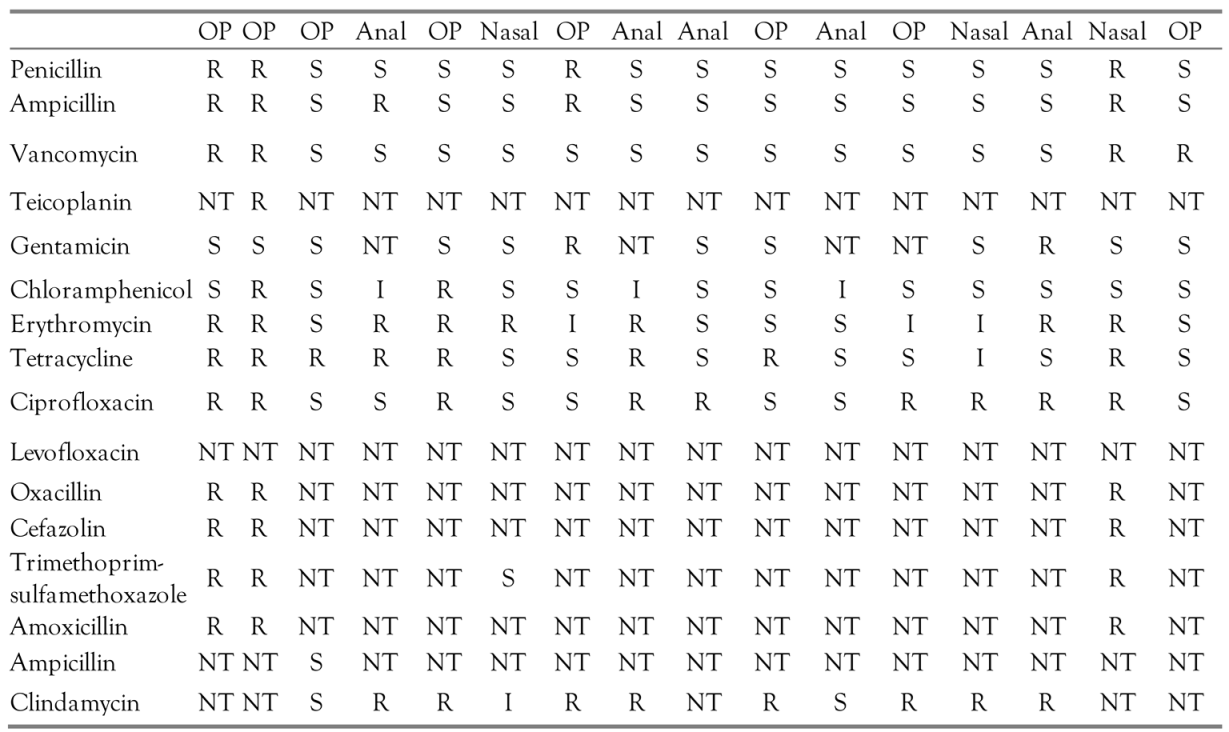

Regarding antimicrobial susceptibility, of the 18 samples that tested positive for Enterococcus, 16 were available for testing. Of these, 75% were susceptible to ampicillin and vancomycin, amounting to 14% of episodes of febrile neutropenia and 22.7% of patients studied.

The remaining isolates, 25% of the total, were resistant to vancomycin, all isolated from the same patient, whose oropharyngeal swab tested positive at the time of admission, then persisting at two recollections. Vancomycin-resistant strains were not isolated from anal swabs at any time, having being persistently found in the oral samples and in the nasal samples. The susceptibility results for the isolates, by site studied, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Antibiograms for the colonizing strains of Enterococcus spp., by site studied.

Discussion

During one year, we evaluated 35 episodes of febrile neutropenia in 22 patients. Most of our patients (74%) had no apparent source of infection at the time of hospital admission. Günalp et al. showed similar results, with 64% of episodes characterized as unexplained fever in a cohort of 200 patients [16]. The frequency of access and exposure to health services, also reported in the literature as being risk factors for colonization by MRSA, were confirmed in our sample, where all patients colonized with MRSA had been hospitalized in the same month or the month before the episode of febrile neutropenia [17].

All patients had at least one of the three analyzed sites colonized by a Gram-positive bacterium. Other authors had demonstrated a change in predominance from Gram-negative to Gram-positive bacteria [1,2,16,18]. A survey conducted from 2008 to 2013 at our institution, which analyzed oncological children, had already indicated Gram-positive bacteria as the agents most frequently isolated in cultures of these patients, the same ones seen in a cohort of Chilean oncological children, where Gram-positive bacteria were isolated in 55% of blood cultures [11].

Staphylococcus aureus colonized 22% of patients, particularly MRSA, which colonized 13.6% of patients and corresponded to 80% of the positive samples by this agent. Our colonization rate by S. aureus was lower than that found in a previous study conducted in 2012 at our institution, which had found a 64% colonization rate in hospitalized non-oncological children, with non-serious illnesses; however, in this same cohort, MRSA was found in only 6% of patients [19]. A colonization rate lower than ours was also observed in a Canadian study conducted with more than 200 non-oncological children, where the colonization rate by MRSA at the time of admission to the emergency department was only 0.4% [20]. Nevertheless, HIV-positive patients were reported to have a MRSA colonization rate around 17%, similar to that found in our patients, which can alert us to the importance of this resistance profile in patients with immunosuppression or more serious illnesses [21,22].

It is also noteworthy that CA-MRSA isolates have been found in hospital setting in two out of the ten positive samples, therefore corresponding to 20% of patients colonized with S. aureus. Described in the literature as community circulating, related to those patients without direct contact with healthcare services, this finding corroborates national data, which point to a hospital invasion by these strains. Mimica et al. reported cystic fibrosis patients colonized with MRSA, with 50% of strains being of the SCCmec type IV, and the same clone colonizing and infecting hospitalized children [19,24,25].

Enterococcus spp. colonized 27% of patients, whereas VRE colonized 4.5% of them. Few are the studies in children with the same profile as that of our patients, and our rate was much lower than that shown in the Chilean study with oncological children, where VRE colonized 52% of patients [26]. A rate similar to ours (4.7%) was found in a cohort of more than 2,000 oncological adults [3]. Also noteworthy is the predominance of vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus spp. isolates colonizing patients that are frequent users of healthcare services and with a serious underlying disease, with these factors having being pointed out in the literature as important risk factors for colonization with VRE [17,23].

When analyzing the positivity of the investigated sites, anal and oropharyngeal swabs showed a higher positivity rate for S. aureus, whereas nasal swabs yielded the highest positivity for Enterococcus spp., respectively 25%, 25% and 20%.

In patients colonized with S. aureus, the oropharyngeal swabs corresponded to 20% of positive samples for that agent—such gain in positivity associated with the investigation of the oropharyngeal site had already been described by Badue et al., who, in studying children with non-severe illnesses, showed a 21% colonization associated with the oropharyngeal site alone [19]. Anal swabs, in turn, corresponded to 40% of the positive samples; Srinivasan et al., when analyzing colonization in children with cancer, had already pointed out the importance of analyzing this site in this population, demonstrating that 28% of the colonized patients carried the agent only in the perineal region [4]. Thus, in our study, by including anal swabs in the colonization analysis, we increased our identification of colonized patients by 20%.

The analysis of other sites such as the axilla, groin, anal region, or oropharynx, has also been indicated in the literature as a way to broaden the study of colonization with CA-MRSA showing that the oropharyngeal site was twice as colonized by MRSA than was the nasal site for this agent [17,19]. Our findings corroborate these data, since CA-MRSA isolates have been identified only in the anal and oropharyngeal sites.

In patients colonized by Enterococcus spp., the nasal and oropharyngeal sites accounted for 22% and 44% of the positive samples for this agent, respectively. The importance of analyzing other sites in pediatric ICU patients was also reported by Yameen et al., who, when performing nasal and rectal swabs, noted that 34% of the samples that tested positive for Enterococcus spp. had been collected from the nasal site [10]. Thus, in our study, by including nasal and oropharyngeal swabs in the analysis of colonization by Enterococcus spp., we increased our identification of colonized patients by 33%. We also highlight the importance of the oropharyngeal site in the detection of VRE, given that all resistant isolates were found in oropharyngeal swabs.

The concurrent colonization by S. aureus and Enterococcus spp., in the multi-site analysis, was also evaluated by Young et al. in more than 1,000 adults admitted to the emergency department, and was not found [14]. Our study showed the importance of the oropharyngeal and anal sites in this evaluation, for 9% of patients presented with colonization by both agents, a finding only seen in the oropharyngeal and anal sites.

The anal and oropharyngeal sites were also important at the recollections made every seven days following hospitalization. In the case of S. aureus, a patient colonized by MRSA had the anal site as the only persistently positive site at the time of recollection, while the other sites tested negative. Recurrent positivity among the colonized patients was reported by Milstone et al. as a risk factor for MRSA infection in ICU children, who, after evaluating more than 3,000 American children, found a bacteremia rate less than 2%, but more than half of the cases corresponding to recurrently colonized children [17]. Our patient did not develop bacteremia caused by the agent during hospitalization, but in the American cohort, more than 80% of MRSA infections occurred after discharge from hospital [17].

In those colonized by Enterococcus spp., in turn, the oropharyngeal site persistently tested positive in all patients undergoing recollection, as well as the analysis on the fourteenth day of hospitalization. Singh et al. analyzed 94 oncological children by describing clearance of colonization with Enterococcus spp. in half of them at around six weeks, while the other part remained colonized for a two year period [28]. We must remember that all our persistently colonized patients used vancomycin during hospitalization, another factor that the literature highlights as being responsible for a more prolonged colonization time in cancer patients [29].

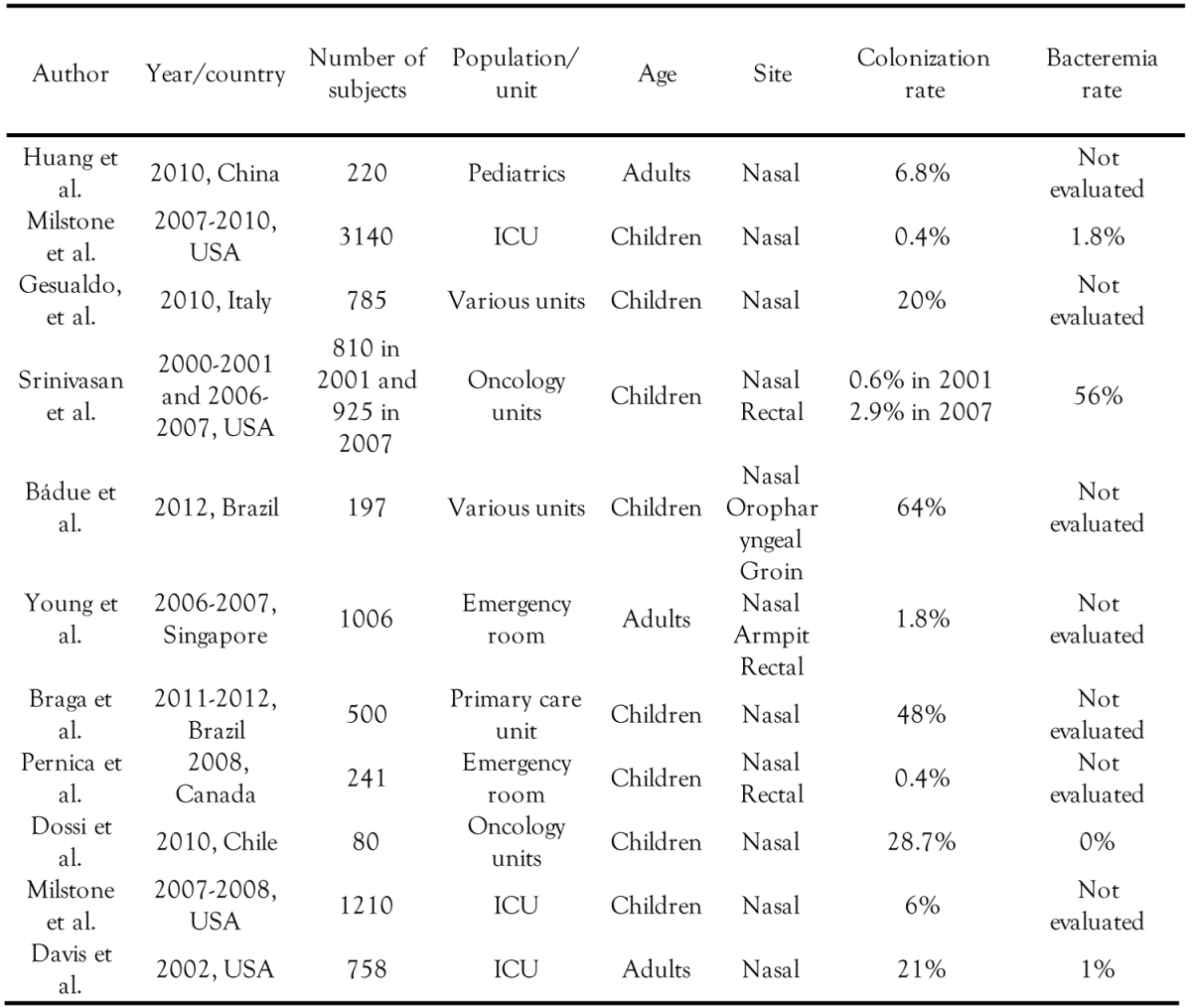

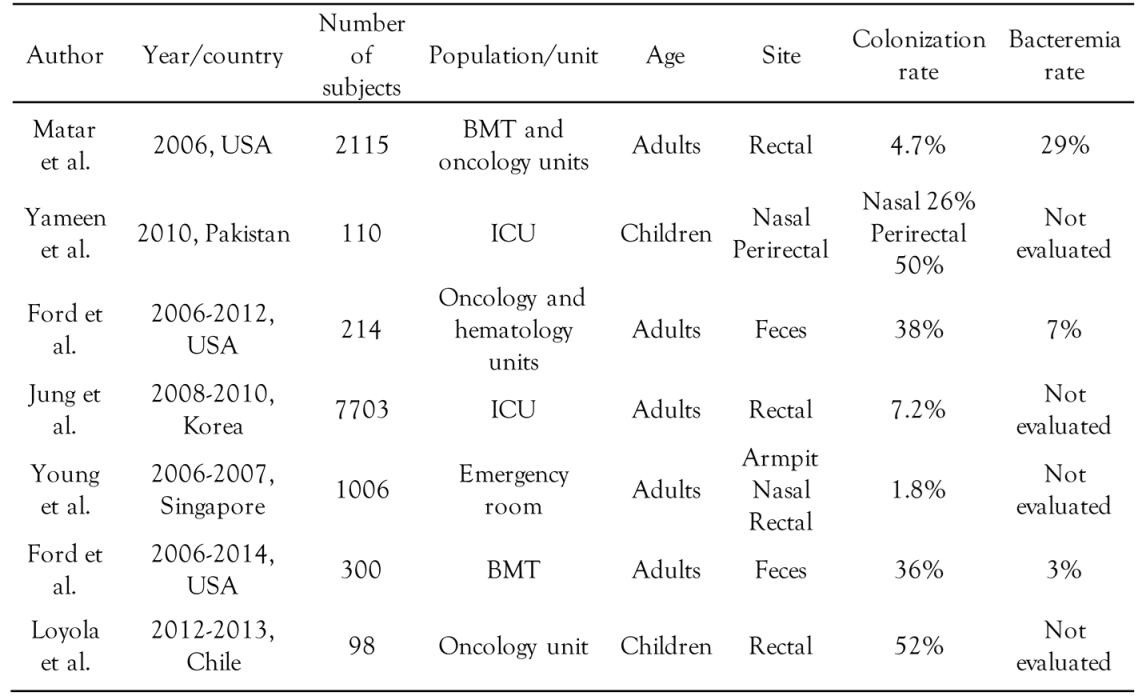

Our infection rates for the two agents studied were similar, 4.5%. The rate of infection by S. aureus in patients colonized by this agent was 20% (1:5), which is high when compared to the Chilean study that evaluated 80 children with cancer. Despite the fact that a higher colonization rate was found (27%), no episode of bacteremia caused by S. aureus was recorded [30]. The rate of infection by Enterococcus spp., in turn, was 16% (1:6) in the colonized patients, which can also be considered to be high when compared to two other studies with similar population: an American study, with a rate of 0.4% in 6 years of follow-up of oncological adults, where only one of the 214 evaluated patients developed an urinary tract infection (UTI) by Enterococcus spp.—this patient had been previously colonized, and a Canadian study, with oncological children known to be colonized by VRE, in whom the UTI rate by this agent was only 3.9% (5:192) [29,31]. Table 6 and Table 7 show previous S. aureus and Enterococcus colonization studies.

Table 6.

Recent studies that evaluated colonization by S. aureus and ICU bacteremia rates.

Table 7.

Studies with different populations that evaluated colonization by Enterococcus spp.

The small sample size associated with the non-use of quinolones in antibiotic prophylaxis and limited use of indwelling devices in this population at our service should be considered, since we could not establish a direct relationship between colonization and risk of infection. Yet, one in every five colonized patients presented with infection by the studied agents.

Conclusions

Our study found limitations related mainly to the small number of patients studied. Still, we observed a significant rate of colonization by S. aureus and Enterococcus spp. in febrile pediatric neutropenic patients following chemotherapy, especially when evaluating three sites: nasal, oropharyngeal and anal.

Analysis of unusual sites for the agents evaluated in the colonization of these patients also proved to be important for the positivity of resistant strains, especially CA-MRSA found in anal swabs, and VRE found in oropharyngeal swabs. Furthermore, these sites proved to be persistently colonized.

It is worth remembering that another risk attributed to colonization is transmission, so that all knowledge about colonization, including the profile of the agent found, clearance time, and identification of risk factors for infection, becomes important for developing strategies for in-hospital control measures.

Finally, especially in this population, expanding the studies on colonization may help to institute an empirical antibiotic treatment aimed at antibiotic adequacy and lower induction of resistance, thereby decreasing the chances of adverse clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors were in charge of sample and data collection, writing, analysis, submission and revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors—none to declare.

References

- Rosa, R.G.; Goldani, L.Z. Factors associated with hospital length of stay among cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.E.; Stewart, L.; Phillips, R. Protocol for a systematic review of reductions in therapy for children with low-risk febrile neutropenia. Syst Rev 2014, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, M.J.; Tarrand, J.; Raad, I.; Rolston, K.V. Colonization and infection with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus among patients with cancer. Am J Infect Control. 2006, 34, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.; Seifried, S.E.; Zhu, L.; et al. Increasing prevalence of nasal and rectal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, L.; Arnan, M.; Liñares, J.; et al. Prospective study of fecal colonization by extended spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in neutropenic patients with cancer. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 4187–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.D.; Waugh, L.K.; Nielsen, M.J.; Paulus, S. Febrile neutropenia in children treated for malignancy. J Infect 2015, 71 (Suppl 1), S27–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, F.; Onori, M.; Bongiorno, D.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in a department of pediatrics: A cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr 2014, 40, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iosifidis, E.; Karakoula, K.; Protonotariou, E.; et al. Polyclonal outbreak of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a pediatric oncology department. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012, 34, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblum, J.; Lin, J.; Kim, M.; Levy, A.S. Repeating blood cultures in neutropenic children with persistent fevers when the initial blood culture is negative. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yameen, M.A.; Iram, A.; Mannan, A.; Khan, S.A.; Akhtar, N. Nasal and perirectal colonization of vancomycin sensitive and resistant enterococci in patients of paediatrics ICU (PICU) of tertiary health care facilities. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís, Y.; Álvarez, A.M.; Fuentes, D.; et al. [Bloodstream infections in children with cancer and high risk fever and neutropenia episodes in six hospitals of Santiago, Chile between 2004 and 2009]. Rev Chilena Infectol 2012, 29, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freifeld, A.G.; Bow, E.J.; Sepkowitz, K.A.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 52, e56–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, V.O.; Tamma, P.; Reich, N.G.; Perl, T.M.; Milstone, A.M. Risk factors for persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children with multiple intensive care unit admissions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013, 34, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.E.; Lye, D.C.; Krishnan, P.; Chan, S.P.; Leo, Y.S. A prospective observational study of the prevalence and risk factors for colonization by antibiotic resistant bacteria in patients at admission to hospital in Singapore. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M100-S23. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-third informational supplement; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Günalp, M.; Koyunoğlu, M.; Gürler, S.; et al. Independent factors for prediction of poor outcomes in patients with febrile neutropenia. Med Sci Monit 2014, 20, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Milstone, A.M.; Carroll, K.C.; Ross, T.; Shangraw, K.A.; Perl, T.M. Community associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in pediatric intensive care unit. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte-Gutierrez, P.; Villalon, L.; Losa, J.E.; Henriquez-Camacho, C. Treatment of febrile neutropenia and prophylaxis in hematologic malignancies: A critical review and update. Adv Hematol 2014, 2014, 986938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bádue Pereira, M.F.; Mimica, M.J.; de Lima Bigelli Carvalho, R.; Scheffer, D.K.; Berezin, E.N. High rate of Staphylococcus aureus oropharyngeal colonization in children. J Infect 2012, 64, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernica, J.M.; Grzyb, M.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Slinger, R.; Suh, K. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children and adolescents admitted to CHEO. Paediatr Child Health 2010, 15, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferreira Dde, C.; Silva, G.R.; Cavalcante, F.S.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in HIV patients: Risk factors associated with colonization and/or infection and methods for characterization of isolates—A systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2014, 69, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.J.; Brooks, J.T.; McAllister, S.K.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization of groin and risk for clinical infection among HIV-infected adults. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 19, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Devrim, İ.; Bayram, N.; et al. Risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococci bloodstream infection among patients colonized with vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Braz J Infect Dis 2015, 19, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimica, M.J.; Berezin, E.N.; Carvalho, R.B. Healthcare associated PVL negative methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with SCCmec type IV. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009, 28, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimica, M.J.; Berezin, E.N.; Damaceno, N.; Carvalho, R.B. SCCmec type IV, PVL-negative, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in cystic fibrosis patients from Brazil. Curr Microbiol 2011, 62, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyola, P.; Tordecilla, J.; Benadof, D.; Yohannessen, K.; Acuña, M. [Risk factor of intestinal colonization with vancomycin resistant Enterococcus spp in hospitalized pediatric patients with oncological disease]. Rev Chilena Infectol 2015, 32, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstone, A.M.; Goldner, B.W.; Ross, T.; Shepard, J.W.; Carroll, C.K.; Perl, T.M. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and risk of subsequent infection in critically ill children: Importance of preventing nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 53, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Esparza, S.; Patterson, M.; Vogel, K.; Patel, B.; Gornick, W. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus in pediatric oncology patients: Balancing infection prevention and family-centered care. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013, 35, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, E.S.; Paras, M.L.; Noubary, F.; Walensky, R.P.; Hooper, C.D. Natural history of colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE): A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossi, C.M.T.; Zepeda, F.G.; Ledermann, D.W. [Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in a cohort of children with cancer]. Rev Chilena Infectol 2007, 24, 194–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C.D.; Lopansri, B.K.; Haydoura, S.; et al. Frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization and infection in patients with newly diagnosed acute leukemia: Different patterns in patients with acute myelogenous and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015, 36, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© GERMS 2017.