Abstract

Echinococcosis is an infectious disease that can remain dormant for years. The most common sites of infection are liver and lungs. Primary cerebral disease is very rare. Here we report on an unusual case of echinococcosis, where the only identifiable lesion was a slowly growing intracranial hydatid cyst. No lesions on the liver identified. The patient is a United States immigrant from rural South India with a chief complaint of progressive weakness and aphasia. Further analysis revealed an interesting association between the clinical, anatomical and hematological findings over time. We conclude that hydatid cyst disease should be considered in patients from endemic areas with long-standing neurological symptoms.

Introduction

Echinococcosis is an infectious disease caused by cestodes from the genus Echinococcus, family Taeniidae. Infection is endemic in Middle East, Mediterranean countries, South America, North Africa and Australia [1]. It is rare in the United States and found mainly in immigrants. Although not considered an endemic country, it has been observed in dogs, pigs and yaks of South India.

The adult tapeworm inhabits the intestine of dogs and causes an indolent human infection that can remain dormant for years. The most common mode of transmission to humans is via consumption of soil, water, or food that has been contaminated with eggs by the fecal matter of an infected dog. In addition, other infected hosts can spread the disease to humans through fecal- oral contact. Deposited Echinococcus eggs can stay viable for up to one year [2]. The eggs hatch to form larvae that deposit leading to the formation of hydatid cysts. The cysts can enlarge over years to decades, without any symptoms. When symptoms do develop, it is usually due to the mass effect on the surrounding tissue rather than from the parasite itself. Cerebral disease is very rare with an occurrence as low as 0.2% of all intracranial space occupying lesions [3].

Case presentation

An 82-year-old female presented to the emergency room after falling at home. She is an American immigrant from South India, Alleppey (Alappuzha) District, living in the USA for 16 years. During this time she did not travel outside the USA or to any rural areas of the country. Prior to presentation, she had been experiencing generalized progressive weakness, memory loss, confusion and aphasia for several months. Aphasia was characterized as difficulty finding the words and naming problems. After the fall, she was unresponsive for several seconds and then became alert.

Her past medical history includes type-2 diabetes, asthma, hypertension and cerebral vascular disease (status post strokes in 2004 and 2008). She suffered mild residual left sided facial droop. One year prior to the fall she had been hospitalized for a severe asthma exacerbation. She had also been experiencing sudden involuntary muscle spasms over this time. Each spasm lasted only a few seconds, with a frequency of 2 to 3 per day, and there was never any loss of consciousness.

On arrival to the emergency room her vital signs were stable. She was alert but lethargic. Her pupils were sluggish but reactive. A mild left sided facial droop was observed. Generalized weakness and lethargy were noted. There were no signs of elevated intracranial pressure. She complained of a mild headache. The only significant laboratory finding was eosinophilia (16%) and a computed tomography (CT) of the brain showed an enlarged cystic lesion. This increased our clinical suspicion for parasitic disease, prompting serological testing which was positive for Echinococcus IgE, with a titer of 1.19. Screening tests were negative for specific IgG antibodies recognizing Taenia solium, the agent causing cysticercosis.

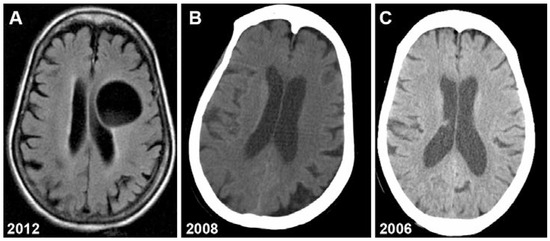

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well circumscribed cystic lesion, with CSF density, measuring 4.5 × 3.7 cm (Figure 1A). This cyst compressed the frontal horn of the left lateral ventricle. There was no surrounding edema and the basilar cisterns were well preserved. A CT scan performed 4 years earlier showed a lesion of 7–8 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). This lesion was not visible on a head CT performed six years earlier (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Neuroimaging showing growth of hydatid cyst over 6 years. A: brain MRI (2012); B: head CT (2008); C: head CT (2006).

This type of lesion was consistent with a persistent hydatid cyst which had grown 5-fold in 4 years. Finally it was the classic imaging findings that confirmed our diagnosis of hydatid cyst.

Electroencephalography showed low frequency waves in the left parasagittal regions suggestive of focal cerebral dysfunction. As mentioned, laboratory studies revealed long- standing eosinophilia that had significantly increased over these past 4 years. CT imaging of the abdomen, thorax and pelvis did not reveal any other lesions.

Given the size of the lesion and the possibility of rupture, the benefits of surgery outweighed the risks, therefor surgery was not performed. A pathological diagnosis was thus not available, and our conclusion was based mainly on imaging findings.

The patient was treated with albendazole 400 mg twice daily. At the 3 months follow-up visit, the cystic lesion remained stable and with the assistance of rehabilitation, weakness improved. The option of surgery was discussed but the patient decided to continue chemotherapy.

Discussion

Echinococcosis is a public health problem in regions such as the Middle East, Mediterranean countries, South America, North Africa and Australia [1]. The two predominant species of medical importance are E granulosus and E multilocularis, which cause cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis, respectively [4]. The disease is endemic in agricultural regions, particularly where sheep are a common intermediate host. Dogs are the definitive host while humans are accidental intermediate hosts, often acquiring the infection during childhood after ingestion of food or water contaminated with feces. The larvae hatch and are carried by the vascular system mainly to the liver and lungs, and less commonly to bones, brain, or heart. To complete the cycle, the dog can directly ingest cysts from infected sheep viscera [4].

Primary disease can develop in any organ but the liver (50–70%) and the lungs (20–30%) represent the most frequent primary locations [1]. After the larvae penetrate the intestinal wall, the liver acts as the first line of defense and is therefore the most frequently involved organ. Transdiaphragmatic migration from the liver can represent one of the mechanisms whereby the parasites spread to the lungs [5]. Alveolar echinococcosis is caused by Echinococcus multilocularis whereas cystic lung disease is caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Alveolar echinococcosis represents a larger public health threat compared to cystic echinococcosis and thus must be differentiated from cystic lung disease. Less than 10% of echinococcosis cases involve the brain, heart bone and soft tissues. Rare cases of other primary locations have been reported: soft tissue [6,7,8], pancreas [9] and musculoskeletal tissue [10].

Some authors report that cerebral echinococcosis has an estimated occurrence of 1- 3% of hydatid cyst diseases [11]. Most of the cases (50–70%) were reported in pediatric populations. For unknown reasons infections restricted to the brain are common in rural areas. In India the reported incidence is as low as 0.2% of all space occupying lesions [3]. The parietal lobe is most commonly affected [12].

The clinical presentation of cerebral hydatid cyst disease is variable. Some people remain asymptomatic while others may have rapid clinical decline [13]. Symptoms develop after the cyst grows enough to cause a mass effect. This can present with signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure such as seizures, papilledema [13,14]. Headache and vomiting are common [14]. Over time progressive weakness and cognitive deterioration are also seen. The growth rate of cerebral hydatid cysts has been reported to be between 1.5–5 cm per year [3]. Complications include secondary bacterial infection, rupture and anaphylactic shock.

The diagnosis of cerebral hydatid cyst disease depends on the probability of exposure combined with pathognomonic features on imaging. CT and MRI show spherical well-defined, thin-walled lesions without surrounding edema. Calcification and surrounding edema are rarely seen whereas these are commonly seen with cerebral alveolar echinococcosis. Ventricle compression is common [15]. MRI and CT scans characteristically show hydatid cysts as spherical, well circumscribed, thin-walled, non-enhancing lesions without peripheral edema (Figure 1A,B). There is usually no surrounding edema or CT enhancement.

The differential diagnosis of cerebral hydatid cyst disease ranges from simple benign cysts such as porencephalic cyst and arachnoid cyst, infectious causes such as cavitary tuberculosis, mycoses, pyogenic abscesses, and finally cystic neoplasms. In contrast to hydatid cysts, porencephalic cyst and arachnoid cysts are nor spherical, nor surrounded entirely by brain substance. Porencephalic cysts are lined by gliotic white matter that can be defined with MRI. Bacterial pyogenic abscesses commonly show associated brain edema and satellite lesions. Cystic tumors of the brain such as astrocytoma and other gliomas are also important to consider. Cystic tumors could be differentiated by the enhancement of the mural nodule. Brain malignancies are also possible hence the importance of whole body imaging and subsequent biopsies. These can usually be differentiated with imaging.

Antibody assays can support radiologic diagnoses but are often not necessary [1]. They are frequently negative in cases confirmed by pathohistology analysis [15]. A positive assay usually indicates a leaky cyst. Eosinophilia is not common (less than 25% cases) and only occurs if there is leakage. Cyst leakage can release antigens that elicit immunological responses that include asthma, membranous nephropathy and life threatening anaphylaxis reactions [12]. There is a known association between echinococcosis, allergies and elevated IgE [16]. It is interesting to note that our patient had a history of asthma and long standing eosinophilia. Her asthma diagnosis was based on symptoms and clinical response to albuterol. It was never formally confirmed with pulmonary function tests. Her eosinophilia was trending up from 2008 to 2012, the same period that the hydatid cyst apparently underwent the most rapid growth. Although it is only speculation, growth of the cyst, with possible associated leakage, may have contributed to her asthma symptoms.

The treatment of choice is surgery which can be curative. The major risk is cyst rupture leading to recurrence or anaphylaxis. Chemotherapy is an alternative which can lead to cyst shrinkage. The treatment of choice is albendazole usually for months to a year. Chemotherapy is most effective in combination with a drainage procedure. Small simple cysts tend to respond better than larger cysts that compartmentalize or calcify.

The patient’s age is very unusual for hydatid disease of the brain. She likely acquired the disease through consumption of water or food that was contaminated by feces of an infected dog. The infection was slowly progressive over many decades.

This highlights the fact that hydatid cyst should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any cystic brain lesion in patients originally from endemic areas. Most cases of echinococcosis in the United States occur in immigrants from areas where sheep farming is popular. Furthermore our patient lived in an urban area while in the United States and grew up in rural South India. Thus, although we cannot prove this, we believe she acquired the infection before immigrating to the USA.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors—none to declare.

References

- Moro, P.; Schantz, P.M. Echinococcosis: A review. Int J Infect Dis 2009, 13, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Parasites—Echinococcosis. Accessed on: March 11, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/echinococcosis/epi.html.

- Gupta, S.; Desai, K.; Goel, A. Intracranial hydatid cyst: A report of five cases and review of literature. Neurol India 1999, 47, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; McManus, D.P. Concepts in immunology and diagnosis of hydatid disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003, 16, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, I.; Saíz, A.; Arrazola, J.; Ferreirós, J.; Pedrosa, C.S. Hydatid disease: Radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics 2000, 20, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarboui, S.; Hlel, A.; Daghfous, A.; Bakkey, M.A.; Sboui, I. Unusual location of primary hydatid cyst: Soft tissue mass in the supraclavicular region of the neck. Case Rep Med 2012, 2012, 484638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaman, E.; Yilmaz, M.; Ada, M.; Yilmaz, R.S.; Isildak, H. Unusual location of primary hydatid cyst: Soft tissue mass in the parapharyngeal region. Dysphagia 2011, 26, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Săvulescu, F.; Iordache, I.I.; Hristea, R.; et al. Primary hydatid cyst with an unusual location--a case report. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2010, 105, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makni, A.; Jouini, M.; Kacem, M.; Safta, Z.B. Acute pancreatitis due to pancreatic hydatid cyst: A case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg 2012, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraket, O.; Zribi, R.; Berriche, A.; Chokki, A. A primary hydatid cyst of the gluteal muscle. Tunis Med 2011, 89, 730–731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, N.; Kiymaz, N.; Etlik, O.; Yazici, T. Primary hydatid cyst of the brain during pregnancy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006, 46, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th edition. Churchill Livingstone. Elsevier; 2005.

- Byard, R.W. An analysis of possible mechanisms of unexpected death occurring in hydatid disease (echinococcosis). J Forensic Sci 2009, 54, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duishanbai, S.; Geng, D.; Liu, C.; et al. Treatment of intracranial hydatid cysts. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011, 124, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bükte, Y.; Kemaloglu, S.; Nazaroglu, H.; Ozkan, U.; Ceviz, A.; Simsek, M. Cerebral hydatid disease: CT and MR imaging findings. Swiss Med Wkly 2004, 134, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuitton, D.A. Echinococcosis and allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2004, 26, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2013.