Abstract

Introduction: To better understand the factors which influence the spread of monkeypox (mpox) infection, the patients that tested positive for mpox virus by real-time PCR in one of the main infectious diseases centers in Bucharest were analyzed in this study, amounting to one third of the confirmed cases in Romania. Methods: Clinical data and laboratory tests were used to build the patient profiles. In the case of positive mpox results, next-generation sequencing of the viral genome was also performed to better comprehend the epidemiology of the infections and the evolutionary path of this virus. Results: Among 47 patients with clinical suspicion of infection, 18 cases tested positive for mpox by real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Patients were mainly men who have sex with men (MSM), often coinfected with HIV-1 (half of the cases) and presenting with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Phylogenetic analysis was performed on 20 samples (15 patients) and indicated that mpox cases in Romania were the result of multiple importing events followed by local spread. A few sequences from European countries (Germany, Italy, France) and USA were found to be closely related to the Romanian sequences. Intra-host evolution was observed and documented in one patient with HIV-1 infection with uncontrolled viremia, showing slightly different mutation profiles in two body compartments. Conclusions: This study showed that the mpox cases from Romania presented similar clinical, epidemiological and mutational features with those reported by other European countries.

Introduction

Infections with the mpox virus (MPXV) have been documented since the 1970s and they were mainly restricted to endemic areas in Central and Western Africa [1]. After the worldwide eradication of smallpox, virus that belongs to the same orthopoxvirus genus, MPXV has been monitored by various public health agencies from Africa and the rest or the world (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA). Before 2022, most of the infections outside of Africa have only been reported in people travelling in endemic areas. However, in 2003 in the USA, a total of 71 zoonotic cases of mpox were identified, all after contact with pet prairie dogs purchased from a shop that had had them caged together with MPXV-infected Gambian pouch rats imported from Ghana [2]. Although it is generally considered a zoonosis, human-to-human transmission has caused outbreaks in the past, the most notable one was reported in 2017 in Nigeria, where 674 people were diagnosed with this infection [3]. Since May 2022, a number of countries in Europe and the Americas have encountered a large number of cases without epidemiological links to endemic areas; the total reached more than 95,900 infections by May 2024 [4].

Being a DNA virus that possesses a DNA polymerase with a proofreading exonuclease activity, MPXV is a slow evolving pathogen. Its diversity is characterized by the existence of two clades, I and II. Clade I, formerly known as the Central African clade, contained the virus originally identified in Congo in the 1970s with a rate of mortality of the disease of about 10% [5]. The second clade, previously known as the West African clade, which has been involved in the 2017 outbreak in Nigeria, has been found to be associated with a lower mortality, of about 3% [6]. Clade II is divided in 2 sub-clades, clade II.A, the West African clade and clade II.B, which is characteristic to the new outbreak outside of Africa. This clade evolved to multiple lineages and sub-lineages suggesting an ongoing evolution. The recent outbreak was suggested to have a single origin, sub-lineage B.1 [7]. It was reported that most of the identified mutations are a hallmark of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3) pressure, with GA to AA and TC to TT mutations being the most frequent [8].

Romania, a central-eastern European country, reported the first mpox case in June 2022 in a young MSM person with HIV-1 infection [9]. By 29 May 2024 Romania reported 47 cases of mpox [10]. During this period, the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș” was one of the institutions involved in diagnosing and treating the patients with mpox. Here we present the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the patients infected with MPXV, as well as a phylogenetic and mutation analysis of the viral strains circulating in Romania.

Methods

Participants and Samples

Between June 2022 and May 2023, fortyseven subjects with suggestive cutaneous or mucosal lesions for mpox presented to the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș” in Bucharest, Romania. Several subjects were epidemiologically linked to other infected persons who were previously diagnosed with mpox. All the patients consent for study enrolment. All of them were tested for STIs. Swabs from cutaneous or mucosal lesions were collected on virus transport media (VTMs) using eSwab collection kit (Copan, Italy) and processed for molecular diagnosis. Clinical data regarding symptoms and other potentially complicating infections (especially HIV) was collected at the patients’ first hospital presentation. Furthermore, in patients with suspected immunodeficiency, HIV-1 viral load (VL), CD3, CD4 and CD8positive T cells in peripheral blood were quantified. In addition, epidemiological data was also recorded by the attending physician, which included declared travel history, known contact with other infected individuals, suspected method of transmission, number of sexual partners in the past 90 days, and whether or not they identified as MSM.

Multiple samples, in dynamics (monthly for up to 5 months), from different sanctuaries (sera, skin lesion, rectal swab) were collected from one mpox positive HIV-1 infected patient with uncontrolled viremia and suppressed immunity in order to evaluate viral intra-host evolution.

Finally, 23 samples from 18 patients were confirmed as positive for MPXV by PCR.

Real Time PCR

Overall, 400 μL of VTMs were used for nucleic acid isolation with QIAamp DSP Virus Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; the elution volume was 60 μL. MPXV screening was done with either Monkeypox Virus Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (VivaChek Biotech, China) or Monkeypox virus genesig® Advanced Kit (Primer Design, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The qPCR reactions were performed on the CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA).

Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Between 100 and 500 ng of extracted nucleic acids were further processed for next generation sequencing (NGS) by using Illumina DNA Prep with enrichment (Illumina, USA) and following manufacturer’s recommendations. Six indexed samples were pooled together for DNA library construction. Each library was purified and quantified using Qubit™ 1X dsDNA High

Sensitivity (HS) Assay Kit on Qubit 4 fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). After denaturation, 10 pM of the library was pairedend sequenced on MiSeq platform using 600 cycle V3 kit chemistry (Illumina, USA).

The reads were polished, trimmed and de novo assembled using the shovill pipeline with SPADES 3.12.067 [11]. The resulted contigs were further used for BLAST. The contigs as well as the raw reads were mapped on the best hit reference sequence. The reads corresponding to MPXV strains underwent reference mapping, with trimming in a 5-repeats iteration fashion and adding a Q30 quality factor threshold, all implemented in Geneious Prime 2023.0.1.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The consensus sequences of the viral strains sequenced were analyzed by means of phylogenetic analysis. Reference sequences were selected from GenBank by using the nucleotide BLAST tool. We have also used the GISAID data base for mpox (EpiPoxTM) to select reference sequences. The first fifteen best matches were retrieved for any analyzed consensus sequence using both GenBank and GISAID nucleotide databases. Duplicates were removed from the final alignment. In total, 271 control sequences were kept for phylogenetic analysis. We used the DECIPHER software in R to generate the alignment that eventually was manually inspected. The tree was generated with the FastTree software that infers approximatelymaximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees. The final tree was visualized with FigTree v1.4.4.

Screening for APOBEC Induced Mutations

The consensus sequences were analyzed for APOBEC induced mutations (GA to AA and CT to TT) with the Hypermut software [12], as implemented on the Los Alamos National Laboratory website, compared to strain MT903340, isolated in 2018 in Nigeria, which belongs to clade II.B.

Results

Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Patients Positive for Mpox

The analysis found 18 mpox positive cases by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) among 47 patients with clinical suspicion of infection. All confirmed cases were in adult men with a median age of 36.5 years (varying between 21 and 51 years); of these 12 (66%) reported unprotected sexual contact; 11 (61%) self-identified as MSM; 5 (27%) were epidemiologically linked to confirmed cases; 4 (22%) had new and/or multiple sexual partners in the previous 90 days, 10 (56%) were infected with HIV-1. Only one of them had been vaccinated against smallpox. The main clinical aspects of the mpox cases treated in our hospital are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with mpox.

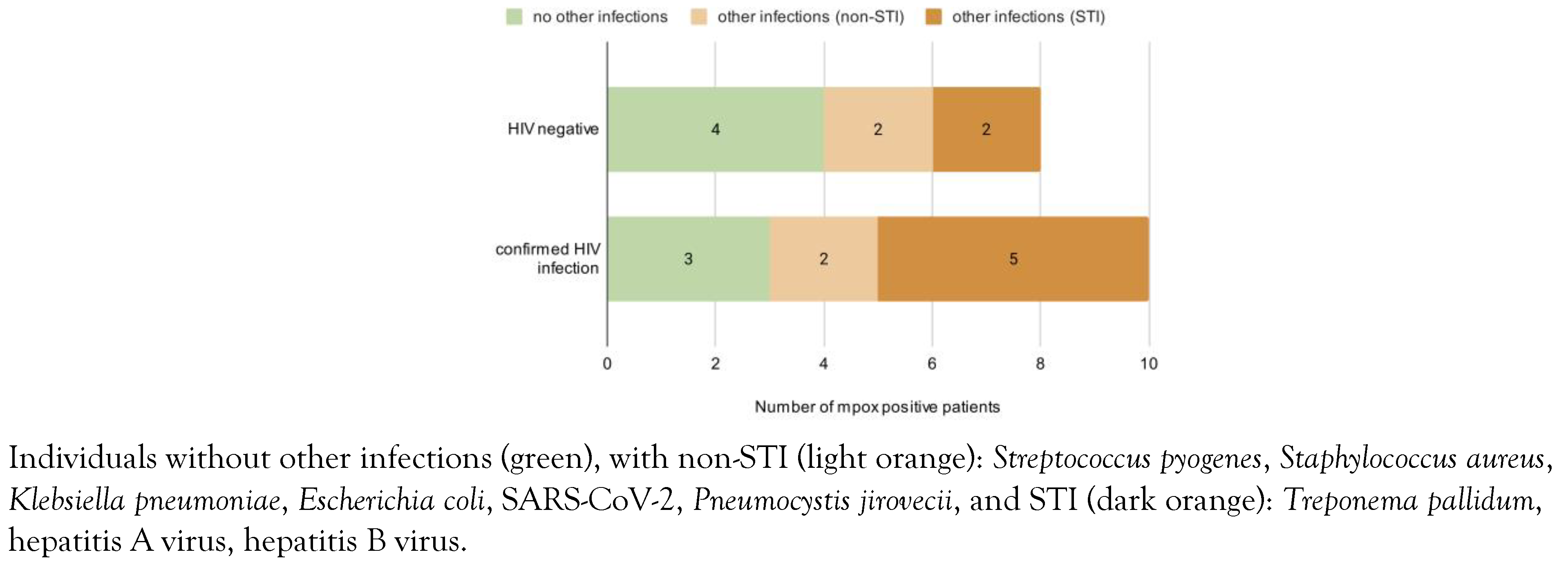

Co-infections and superinfections were also a central feature of these individuals: more than half of the patients (n=10, 55%) also had HIV-1 infection. Of those, 9 had a previous diagnosis of HIV infection, all of them were on antiretroviral therapy and had controlled infections (4 with undetectable viremia, 4 with a value of less than 20 copies/mL, and 1 with a VL of 40 copies/mL). One case was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection concurrently with MPXV, as well as many other co-infections (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), STIs (latent syphilis) or with opportunistic pathogens (Candida albicans). Alongside HIV, most patients were found to also have co-infections and superinfections (Figure 1), such as syphilis, hepatitis A and B. Most of the people living with HIV had a good immunological status with CD4 counts higher than 500 cells/μL. Two of them were immunediscordant with low CD4 counts despite viral suppression (VL < 20 copies/mL and CD4 = 97 cells/μL; VL = 40 copies/mL and CD4 = 316 cells/μL).

Figure 1.

Comparison of patients with mpox by HIV status.

Only 5/18 (27%) had reported travel history: 4 in Europe (France, Italy, Bulgaria and the Netherlands), 1 in Asia (Israel), but none in mpox endemic areas.

Phylogenetic Analysis

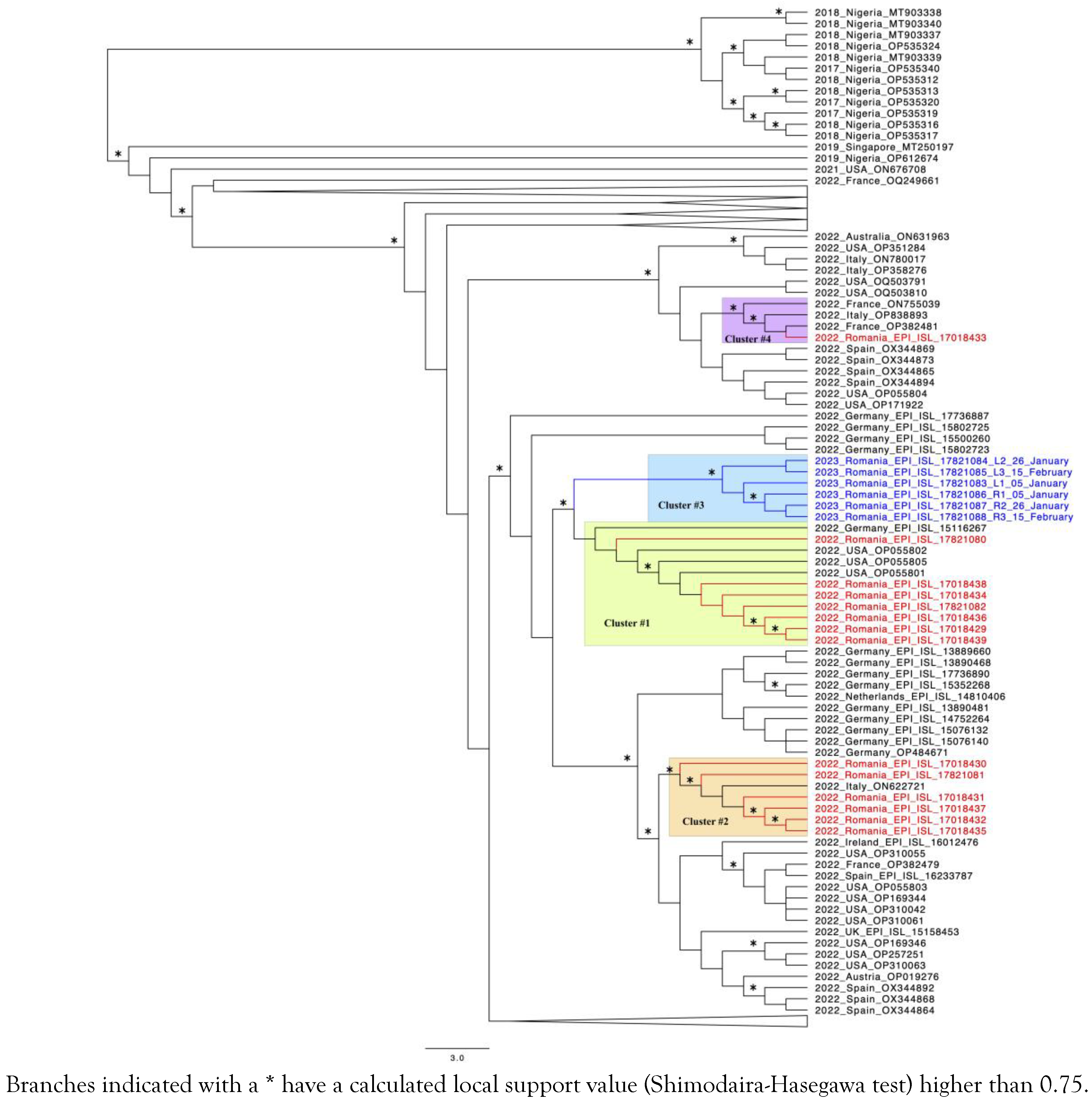

A total of 23 samples from 18 patients were sequenced by shotgun approach, but full genomes with good coverage were obtained only for 15 patients (20 samples). One patient with uncontrolled HIV-1 infection was sequenced in different stages of mpox infection and from two biological sites, rectal swab and skin lesions. In total, 6 MPXV whole genome sequences (WGS) were obtained for this patient, the corresponding sequences were marked in blue in Figure 2. To identify close phylogenetic relationship, we have compared the Romanian MPXV sequences with reference sequences reported in other parts of the world. The selection criterion for the control sequences was the similarity score (obtained via BLAST) compared to our sequences.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the 20 sequences obtained from this research.

The phylogenetic analysis indicated that the Romanian mpox epidemic experienced multiple importing events followed by local dissemination, as proven by the existence of several well defined transmission clusters. The largest cluster (number 1, highlighted in green) consists of 7 Romanian sequences that were grouped together with three sequences from the USA and one from Germany. The second cluster (highlighted in orange) is represented by 6 Romanian sequences and one other from Italy. One of these patients reported Italy (Milan) as the possible place of infection. Cluster 3 is formed by sequences corresponding to the one patient with HIV infection who was extensively monitored (highlighted in blue, with the sequences also marked in blue). One sequence from a Romanian patient who declared travel to Israel prior to his mpox diagnostic clustered together with two sequences from France and one from Italy (number 4, highlighted in purple). In the public databases, there are only a couple of sequences available for Israel with none of them being closely related to the corresponding Romanian sequence.

Mutational Screening

APOBEC3 pressure is one of the driving forces for MPXV evolution [13]. Our results using the Hypermut software for APOBEC3 mutational print identified an average of 36 transitions G to A and 28 transitions C to T (Supplementary Table S1). No differences were found between HIV positive and HIV negative patients, regardless of HIV viremia or CD4 cell counts.

However, the patient living with HIV extensively monitored, presenting high viremia and low CD4 counts, was evaluated more thoroughly (Supplementary Figure S1). Using the built-in tools available on the GISAID platform the mutation analysis performed at three different time points (covering more than a month of hospitalization) in two different sites: rectum and skin (facial lesion), a summary of which can be seen in Supplementary Figure S1.B). Overall, there were 5 mutations that were found in all 6 sequences in the following genes: E11L (V619I), F4L (E253K), G8L (D212N), G10R (R194H), and Q1L (M107I). When comparing the two reservoirs, the E229K substitution in the F1L gene (nucleotide substitution C to T at position 42674) was identified only in the rectal swabs. Furthermore, mutations in the A23R gene were present only in those strains that did not contain 2 deletions in the B10.5R gene.

Discussion

Mpox is a zoonosis triggered by a virus belonging to orthopoxviruses; the disease is similar to smallpox but with milder symptoms. In some areas of Africa MPXV has been endemic for over 50 years; however, until recently, only sporadic cases were reported outside of Africa [14]. The first observations about the 2022 mpox outbreak indicated that MSM were mainly affected and no direct links with travels to endemic countries were found [15]. The patients presented rash on the face, extremities, oral epithelium, and genitalia, headaches, flu-like symptoms (fever, myalgia and lethargy) and lymphadenopathy [16]. The presence of lymphadenopathy in mpox is a consistent distinguishing aspect, but testing the vesicle lesion swab specimen by PCR remains the reliable method of diagnosis. Almost half of the cases of mpox were reported in people living with HIV and had an impact on disease evolution with uncontrolled HIV-1 viremia [17].

In total, about one third of the confirmed cases in Romania were processed within this study [10]. Our results show that all cases of infection were in young males, most of them (61%) self-identified as MSM, already had a diagnosis of HIV and were co-infected with other STIs. As compared to previous studies that identified mpox almost exclusively in MSM in our study 3 of 18 subjects reported to be heterosexuals and 3 others did not answer [18]. Romania is one of the traditional countries where lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people still face social stigma and discrimination that impact negatively this particular community [19]. This could determine their reluctance to declare the sexual orientation and could possibly explain these results. Nevertheless, as part of the European Union where LGBT persons' health and human rights are protected, Romania showed important improvements in recent decades. Changes can also be observed when looking at the data on HIV-1 infections in Romania: the number of the infections transmitted via MSM contact has been continuously rising in the last 10 years [20]. This is, at least partially, due to a higher number of men willing to declare their MSM orientation.

Most of the patients in our study had a mild disease, with only two needing hospitalization (both were co-infected with HIV) and no fatal case was recorded. For the extensively monitored patient that was concurrently diagnosed with acquired immune deficiency syndrome, the process of clearing the MPXV was much longer, with the improvement of immune status being associated with a reduction in MPXV viremia (Supplementary Figure S1).

These observations are in agreement with previous reports showing a mild evolution of the disease, sporadic severe illness and deaths. However, the fatality rate increased from less than 0.1% to 15% in patients with poor immunologic status (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) [21].

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that mpox cases in Romania resulted from multiple introductions followed by local spread, mainly in the Bucharest metropolitan area. MPXV sequences reported by a few European countries (Germany, Italy, France) and USA proved to be closely related to Romanian sequences, in accordance with the travel history of the patients. The sequences corresponding to the patient with HIV infection (6 sequences at 3 different time points) form a single well supported cluster suggesting no reinfection occurred.

APOBEC is a class of cytidine deaminases, restricted to vertebrates, that edits nucleic acids. In humans, the APOBEC family consists of 11 members: AID (activation induced deaminases), APOBEC 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D, 3F, 3G, 3H, 4. All members of APOBEC3 (A3) family were shown to have antiviral function inducing hypermutations in viral RNA/DNA. Moreover, APOBEC mutagenic function was also linked to cancer. Among the targeted viruses are: HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), herpes viruses, parvovirus, papillomaviruses and recently mpox [22]. It was shown that HIV-1 infection induces the expression of A3, but also develops a protection mechanism mediated by Vif. This viral protein induces A3 ubiquitination by an E3 ubiquitin ligase and its proteasomal degradation. A recent study reported that A3 members are able to hetero-oligomerize in order to achieve protection against Vif [23]. The A3F was reported to be responsible for deamination of cytidine residues in the MPXV genome [24]. This might explain why no differences in A3 mutational prints between subjects with and those without HIV-1 were observed, although an inhibition of A3 by HIV-1 might have been expected, especially for patients with unsuppressed viremia (and consequently with high Vif expression).

Our data showed that there were differences in the mutational profile when comparing sequences from rectal swabs and skin lesions: additional mutations (silent and non-silent) were encountered in rectal swabs during subsequent sampling. It was shown that A3s are constitutively expressed in lymphoid cells and tissue and increase after T cell stimulation. Moreover, some members were found outside immune compartment, in the lungs (A3A, A3B, A3C, A3D and A3H), adipose tissue (A3A), colon and cervix (A3F, A3H) [25]. Since A3F, the major MPOXV pressure, seems to be preferentially expressed in some tissues, a distinct virus evolution at different sites is expected.

One limitation of the current study is that we have analyzed only the cases who presented in one infectious diseases hospital in Bucharest, representing one-third of the total reported cases for this country. These patients were living and working in Bucharest metropolitan area.

Conclusions

The present study showed that MPXV sequences were similar with other European sequences, suggesting that several individual introductions were followed by local transmission; the virus has the capacity to evolve, even within a single individual following APOBEC rather than other immune mediated strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.18683/germs.2024.1425/s1, Table S1: Number of APOBEC3 specific hypermutations relative to the 2018_NIGERIA_MT903340 mpox reference sequence. Analysis performed with the Hypermut program through the Los Alamos National Laboratory website; Figure S1: (A) Timeline of medical interventions and sample collections for the ART-naive patient who presented with multiple infections. For the MTB treatment, he was given isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (HRZE). The antiretroviral therapy consisted of FTC/TAF and DTG according to the current guidelines, which also recommended delaying the start of ART for 1 month after the start of MTB treatment. After the PCR diagnosis of mpox infection, the patient also started treatment with tecovirimat for 1 month. (B) Overview of mutations according to the GISAID database (gene and effect on translation) for the 6 sequences obtained from our extensively monitored ART-naive HIV-infected patient. The two reservoirs are labelled as L (skin lesion) and R (rectal swab). (C) Summary of the evolution of both the HIV and mpox infections (relative viral load normalized to the maximum measured levels) and the immunological reconstitution of the patient (in terms of rising CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts) following the start of ART at the end of 2022.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SP, LB, DO; Methodology: RH, SP, LB, OV, AIT, AN; Formal analysis: RH, SP, LB, OV, AIT; Clinical investigation: AN, OV; Data curation: RH, OV, LB, AIT; Writing – original draft preparation: RH, SP, LB, OV, AIT, AN, DO; Writing – review & editing: RH, SP, LB, OV, AIT, AN, DO; Visualization: RH, OV, AIT, LB. Supervision: SP, DO; Project administration: LB, SP. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Marius Surleac, PhD, from the Molecular Genetics Department of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș” for genome assembly and bioinformatics analysis of mpox sequences.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

Ethical Approval and Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all the patients which have been included in this study. Furthermore, this investigation adheres to the workplace guidelines regarding conducting scientific research and publishing the resulting findings.

Nucleotide accession numbers

The WGS consensus sequences generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI database and have the following accession numbers: OR500067 - OR500086.

References

- Breman, J.G.; Kalisa-Ruti Steniowski, M.V.; Zanotto, E.; Gromyko, A.I.; Arita, I. Human monkeypox, 1970-79. Bull World Health Organ. 1980, 58, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, M.G.; Davidson, W.B.; Curns, A.T.; et al. Spectrum of infection and risk factors for human monkeypox, United States, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. Update on Monkeypox (MPX) in Nigeria. NCDC, 19 Jun 2022. 2022. Available online: https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/files/sitreps/4f9bc59b967d1f4b19d61358595d3546.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/monkeypox (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Jezek, Z.; Szczeniowski, M.; Paluku, K.M.; Mutombo, M. Human monkeypox: clinical features of 282 patients. J Infect Dis. 1987, 156, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Sharma, A.R.; Dhama, K. Evolution, epidemiology, geographical distribution, and mutational landscape of newly emerging monkeypox virus. Geroscience 2022, 44, 2895–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isidro, J.; Borges, V.; Pinto, M.; et al. Addendum: Phylogenomic characterization and signs of microevolution in the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprea, C.; Ianache, I.; Piscu, S.; et al. First report of monkeypox in a patient living with HIV from Romania. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022, 49, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Global Map & Case Count. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/world-map.html (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Seemann, T. Shovill. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/shovill (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Rose, P.P.; Korber, B.T. Detecting hypermutations in viral sequences with an emphasis on G --> A hypermutation. Bioinformatics. 2000, 16, 400–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumonteil, E.; Herrera, C.; Sabino-Santos, G. Monkeypox virus evolution before 2022 outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023, 29, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetifa, I.; Muyembe, J.J.; Bausch, D.G.; Heymann, D.L. Mpox neglect and the smallpox niche: a problem for Africa, a problem for the world. Lancet 2023, 401, 1822–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Fu, L.; Wang, B.; et al. Clinical characteristics of human mpox (monkeypox) in 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M.; LePage, T.; Bester, V.; Yoon, H.; Browne, F.; Nemec, E.C. Mpox (formally known as monkeypox). Physician Assist Clin. 2023, 8, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candela, C.; Raccagni, A.R.; Bruzzesi, E.; et al. Human monkeypox experience in a tertiary level hospital in Milan, Italy, between May and October 2022: epidemiological features and clinical characteristics. Viruses 2023, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoli, G.N.; Van Caeseele, P.; Askin, N.; Abou-Setta, A.M. Comparative evaluation of the clinical presentation and epidemiology of the 2022 and previous Mpox outbreaks: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). 2023, 55, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. EU LGBTI survey II - A long way to go for LGBTI equality. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/lgbti-survey-country-data_romania.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Compartment for monitoring and evaluating HIV/AIDS infection in Romania (CNLAS). “Evolution of HIV in Romania”. Available online: https://www.cnlas.ro/images/doc/31122022_rom.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- European Centre for Disease Control. Factsheet for health professionals on Mpox (monkeypox). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topicsz/monkeypox/factsheet-health-professionals (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Pecori, R.; Di Giorgio, S.; Paulo Lorenzo, J.; Nina Papavasiliou, F. Functions and consequences of AID/APOBEC-mediated DNA and RNA deamination. Nat Rev Genet. 2022, 23, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, M.; Annan Sudarsan, A.K.; Gaba, A.; Chelico, L. Stability of APOBEC3F in the presence of the APOBEC3 antagonist HIV-1 Vif increases at the expense of co-expressed APOBEC3H haplotype I. Viruses 2023, 15, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suspène, R.; Raymond, K.A.; Boutin, L.; et al. APOBEC3F is a mutational driver of the human monkeypox virus identified in the 2022 outbreak. J Infect Dis. 2023, 228, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refsland, E.W.; Stenglein, M.D.; Shindo, K.; Albin, J.S.; Brown, W.L.; Harris, R.S. Quantitative profiling of the full APOBEC3 mRNA repertoire in lymphocytes and tissues: implications for HIV-1 restriction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 4274–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2024.