Abstract

Introduction: Brevundimonas spp. are rare and opportunistic pathogens which may cause infections in patients who are immunocompromised or have underlying disease. Case report: Two cases with a microbiological diagnosis of Brevundimonas aurantiaca and Brevundimonas spp. are presented. Both occurred in immunocompromised patients with post-chemotherapy febrile neutropenia for B-type acute lymphoblastic leukemia and hepatoblastoma. Antibiogram findings showed resistance to quinolones, ceftazidime, and intermediate resistance to cefepime, being susceptible to carbapenems and aminoglycosides. The cases responded favorably to the administration of carbapenem. Conclusions: The identification of the species and antimicrobial susceptibility profile favor response to infection, denoting the importance of species identification and the performance of an antibiogram to determine the different susceptibility profiles described in the literature on this emerging pathogen.

Introduction

The species of Brevundimonas spp. belong to the Alphaproteobacteria class and the Caulobacteraceae family. [1,2] The genus Brevundimonas was proposed in 1994 with several species that previously belonged to other genera, mainly the Pseudomonas genus. [2] Currently, the genus consists of 37 species, [3] the main species are B. diminuta and B. vesicularis, non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli, catalase, and oxidase-positive, aerobic, and non-spore-forming, which have a polar flagellum that provides mobility. In addition, these species have been isolated in multiple environments, mainly in water reservoirs and underwater sediments. [1,4]

Infection by Brevundimonas is usually observed in patients with an underlying disease, especially in immunosuppressed patients. [1,5] There is little information on the mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in this genus, although resistance to cotrimoxazole, third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, piperacillin/tazobactam, and even colistin has been reported. [5,6]

There are few reports of Brevundimonas in pediatric patients, therefore, we present two cases of Brevundimonas infection in immunocompromised pediatric patients diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and hepatoblastoma undergoing chemotherapy and surgical treatment, respectively. The patients evolved favorably and achieved microbiological clearance in control blood cultures with the use of carbapenems.

Case reports

Case 1

This case was a 5-year-old female patient from Cajamarca-Peru, with a history of Down syndrome, single kidney, hypothyroidism and type B acute lymphoblastic leukemia, who received multiple chemotherapy schemes (induction IA, induction IB, Block I, Block II and reinduction of 5 drugs) which failed, thereby requiring palliative management. During chemotherapy, the patient had episodes of febrile neutropenia and received broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment. Approximately 5 months after the last cycle of chemotherapy, the patient was hospitalized for febrile neutropenia. Auxiliary examinations revealed a hemogram with leukocytes 8660 cells/µL, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 519 cells/µL, blast cells 73%, C-reactive protein (CRP) 199 mg/L, and procalcitonin (PCT) 0.81 ng/mL.

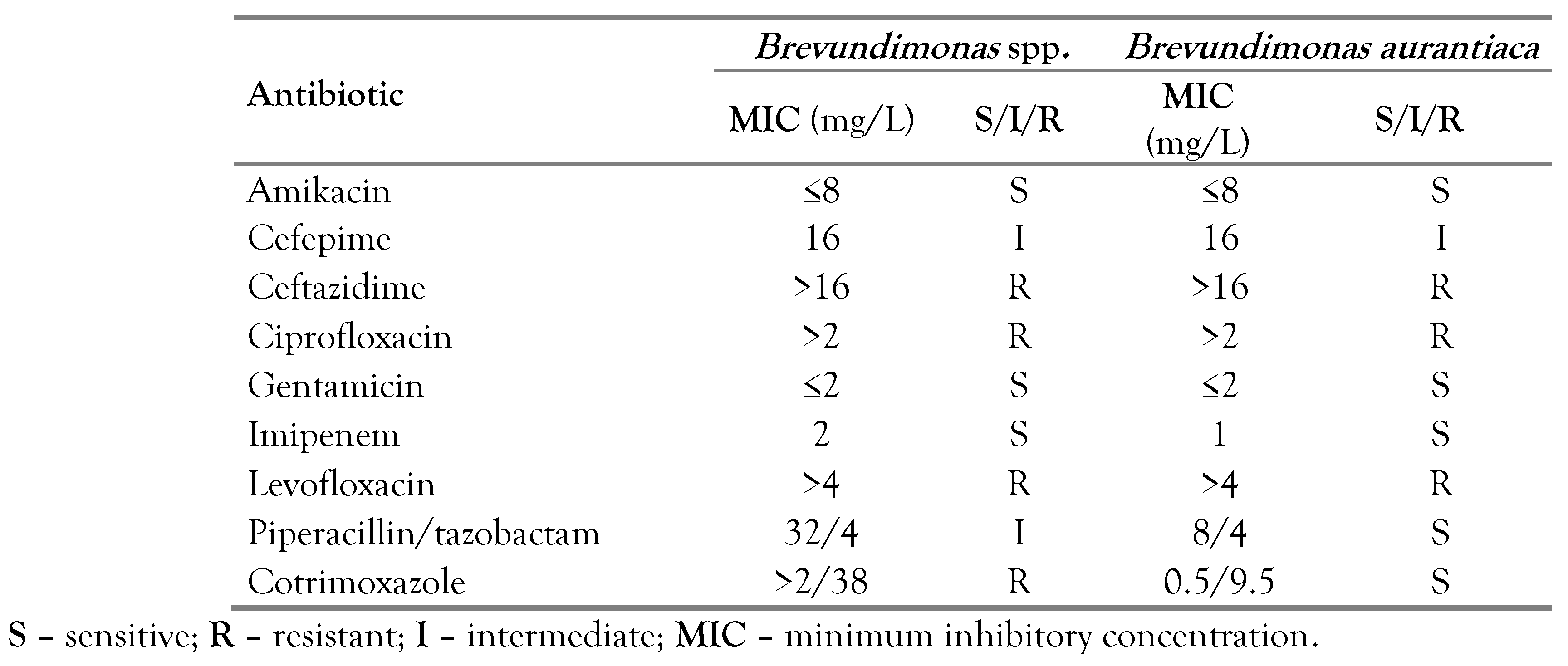

Treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam (320 mg/kg/day) was started, but due to the persistence of fever after 4 days of effective therapy, it was decided to switch to meropenem (60 mg/kg/day), with a favorable response. Blood culture results were positive for B. vesicularis and the antibiogram showed susceptibility to amikacin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] ≤ 8 mg/L), gentamicin (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L), piperacillin/tazobactam (MIC 8/4 mg/L), cotrimoxazole (MIC ≤ 0.5/9.5 mg/L) and imipenem (MIC 1 mg/L) and resistance to ceftazidime (MIC > 16 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (MIC > 2 mg/L) and levofloxacin (MIC > 4 mg/L). In addition, intermediate susceptibility to cefepime (MIC 16 mg/L) was reported (no susceptibility test to meropenem). Despite clinical and laboratory improvement, the isolation of microorganisms in the blood culture after more than 5 days of treatment with meropenem led to the decision to change the therapeutic regimen, to piperacillin/tazobactam (320 mg/kg/day) plus amikacin (15 mg/kg/day) based on the antibiogram results. However, after 3 days of therapy, the patient again became febrile with elevated inflammatory markers, and the administration of meropenem was reinitiated (120 mg/kg/day), completing a total of 11 days of therapy with favorable evolution, a reduction in inflammatory markers (PCT: 0.23 ng/mL), and negative blood culture controls. The patient had a Port-A-Cath catheter that was removed due to infection during antimicrobial treatment.

Case 2

A female patient aged 1 year 9 months from Lima-Peru, was hospitalized with a diagnosis of hepatoblastoma with suspected metastasis due to the presence of pulmonary nodules. The patient was administered Block A chemotherapy schemes with cisplatin and doxorubicin; and Block B with carboplatin and doxorubicin, showing partial response. Approximately 7 days after the last chemotherapy scheme, the patient presented febrile neutropenia without a focus. Physical examination revealed a palpable abdominal mass located in the hypochondrium and right flank. Auxiliary tests showed a leukocyte count of 1460 cells/µL, ANC: 160 cells/µL, PCT: 0.1 ng/mL and CRP: 4.1 mg/L. The result of the peripheral blood culture test was positive for Brevundimonas spp. with an antibiogram showing susceptibility to amikacin (MIC ≤ 8 mg/L), gentamicin (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L), and imipenem (MIC 2 mg/L), and resistance to ceftazidime (MIC > 16 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (MIC > 2 mg/L), levofloxacin (MIC > 4 mg/L), cotrimoxazole (MIC > 2/38 mg/L), and intermediate susceptibility to cefepime (MIC 16 mg/L) and piperacillin/tazobactam (MIC 32/4 mg/L).

Empirical antimicrobial treatment was started with piperacillin/tazobactam (320 mg/kg/day), received for 3 days. However, as the febrile episodes persisted and the results of blood cultures became available, the antimicrobial therapy was changed to meropenem (60 mg/kg/day) completing a total of 14 days of therapy with favorable clinical evolution and negative control blood cultures. The patient had a Port-A-Cath catheter that was not removed due to infection. Subsequently, primary tumor resection surgery and hepatectomy was performed.

Microbiological identification

The initial microbiological identification and antibiogram were performed at the Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño San Borja, Lima-Peru, using the Phoenix automated system, reporting B. vesicularis in both cases. The susceptibility profile is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Susceptibility report of the isolates reported in the National Institute of Children’s Health San Borja – Peru.

The microbiological sample of case 1 was sent to the Laboratory of the Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima-Peru, for molecular typing. A fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers 8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1510R (5′-GGTTACCTTTGTTACGACTT -3′) under conditions previously described. [7] The amplified product was resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with 5% GreenSafe DNA Gel Stain, (Canvax Biotech, Spain), excised and purified using the E.Z.N.A. Gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, GA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified product was sent to Macrogen (South Korea) for sequencing. The presence of a member of the genus Brevundimonas was confirmed by comparison of the fragment in BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) matching the 16S rRNA of B. aurantiaca (strain CB-RT = ATCC 15266T = DSM 4731T—GenBank access: AJ227787) with 100% identity. In case 2, molecular identification was not performed.

Discussion

Brevundimonas spp. is not frequently implicated in human infections, and in previous reports, it was observed in patients with underlying diseases. Most cases are attributed to nosocomial sources, although some community-acquired cases have been reported. It is usually mainly found in blood samples. [6,8,9,10] However, the isolation of Brevundimonas species has been reported in other samples such as urine, joint fluid, ascitic fluid, respiratory secretions, and vaginal secretions. [11,12,13,14,15,16]

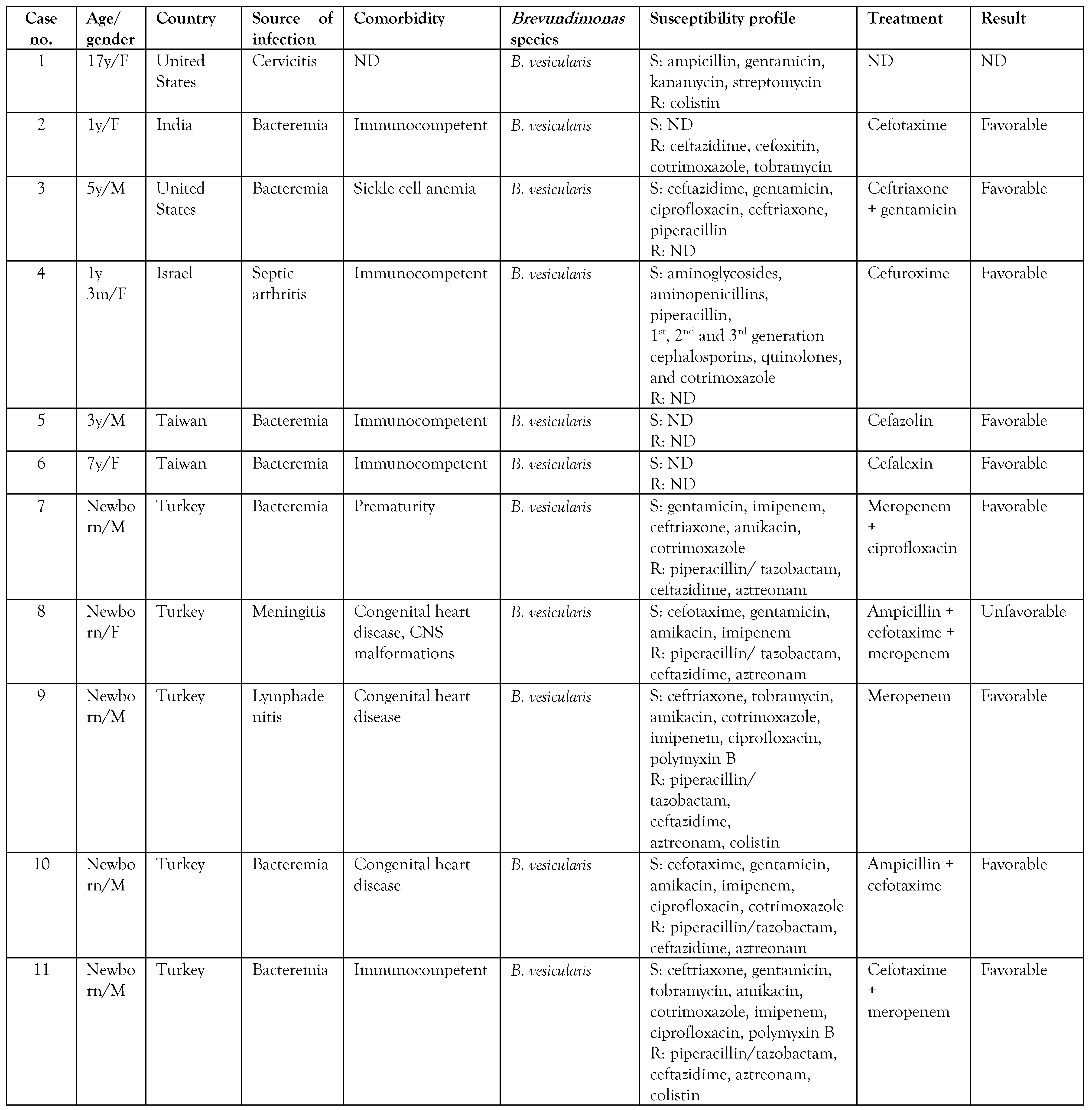

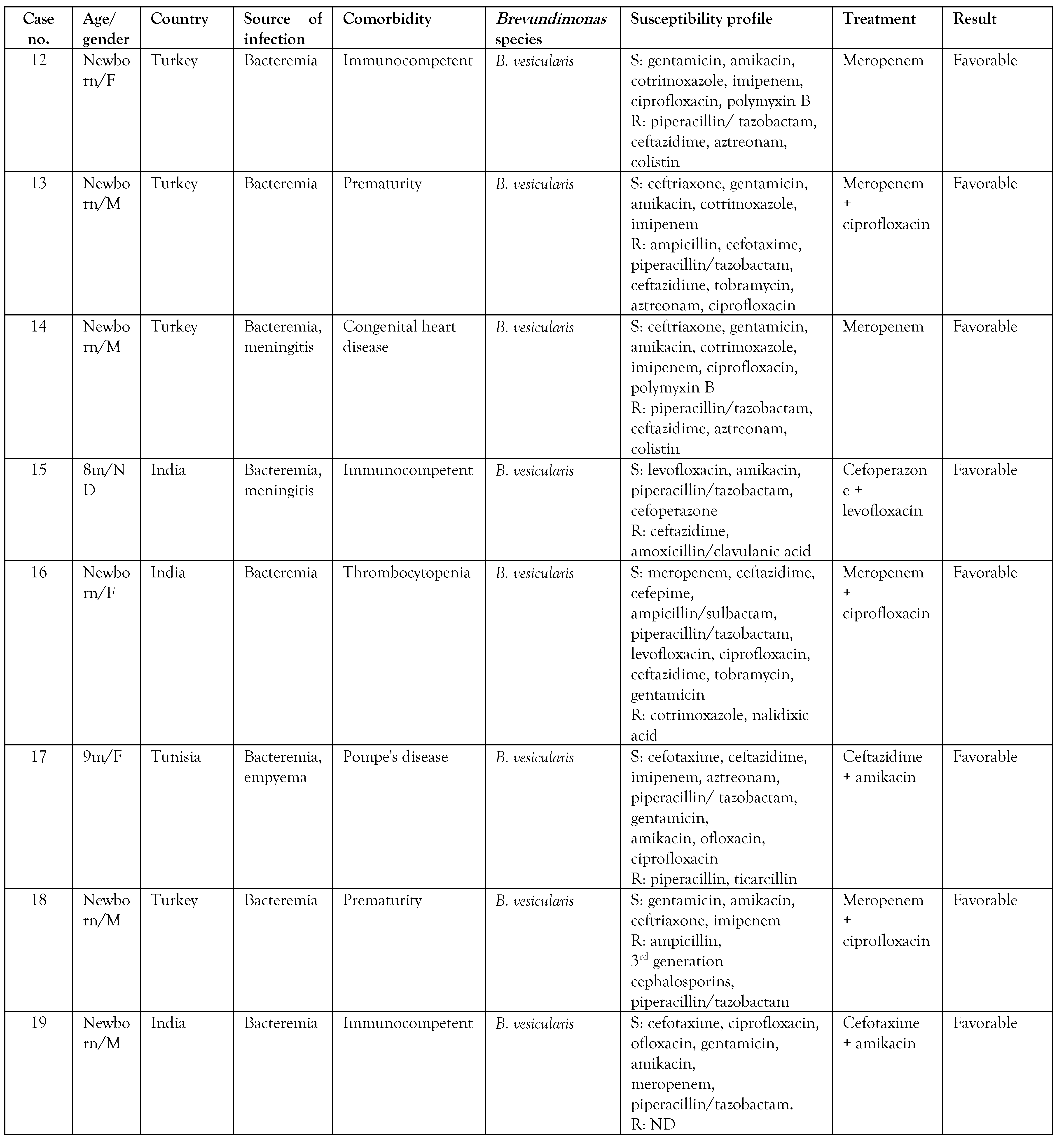

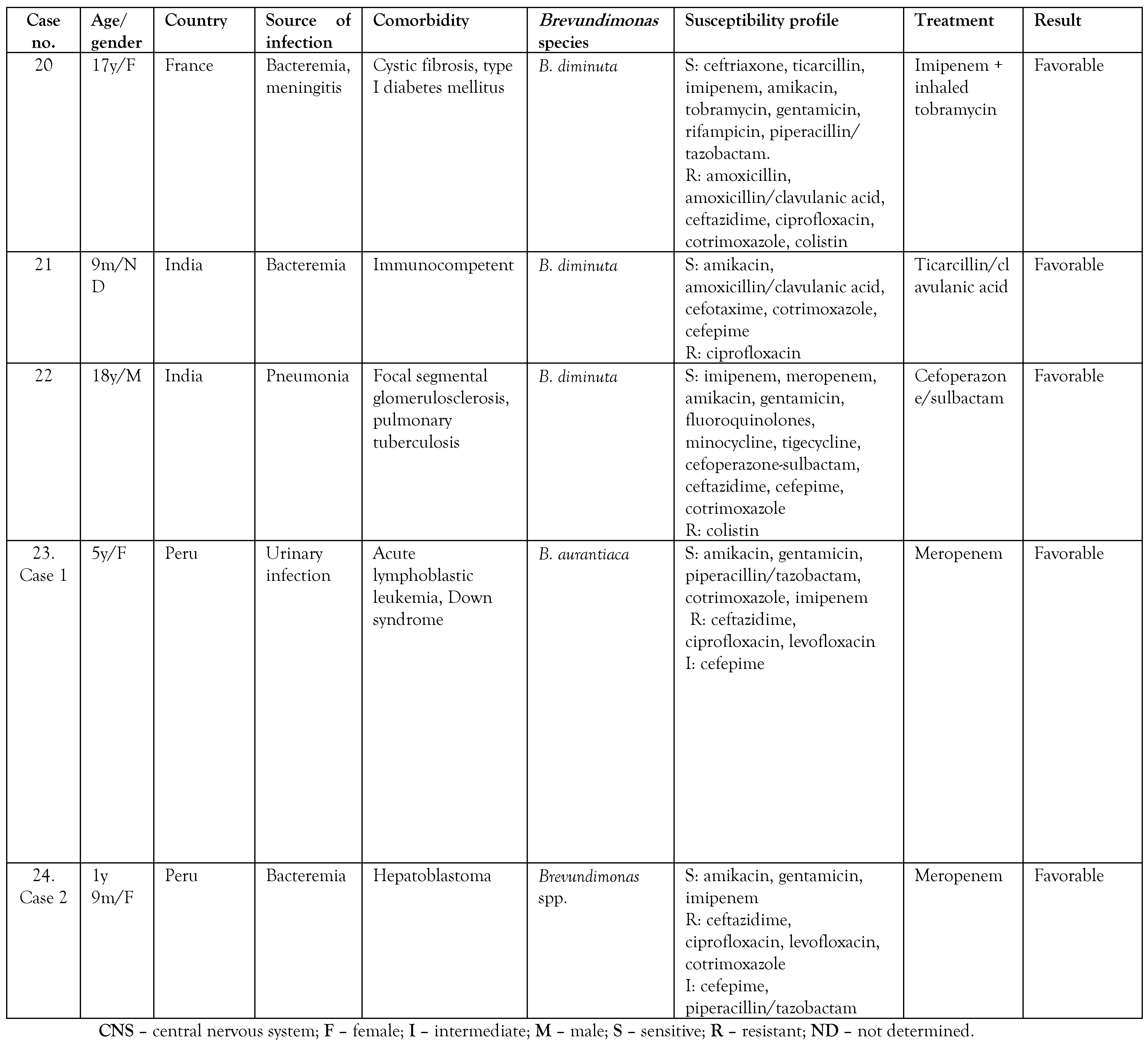

A search was made in the PubMed and Google Scholar databases on isolates of Brevundimonas spp. in pediatric patients, and the summary of the cases is presented in Table 2. A total of 24 cases reported in pediatric patients were found, including the 2 cases presented in the present article. [6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21] Of these, 19 cases corresponded to infections by B. vesicularis, 3 to B. diminuta, one case to Brevundimonas spp., and one case to B. aurantiaca, the latter being identified in the present report by molecular methods. To date, only one case of human infection by B. aurantiaca has been previously reported. [22] Likewise, infection by Brevundimonas species in children was more frequently observed in patients under 1 year of age in 60% of the cases.

Table 2.

Characteristics of pediatric patients diagnosed with infection by Brevundimonas spp. [6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21].

The cases occur mainly in patients with an underlying disease such as chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis, sickle cell anemia, acute leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, diabetes mellitus, congenital heart disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, glomerulopathy, and cystic fibrosis, due to the immunological defect, and thus, Brevundimonas can be considered an opportunistic pathogen. [1,5,6] However, some cases have also been reported in apparently immunocompetent patients. [8,12,17] Table 2 shows that the reports of pediatric patients were more frequent in patients with congenital heart disease (4/24), premature newborns (3/24), and in 9/24 no previous underlying diseases were described. There are reports of Brevundimonas infection in adult cancer patients, but in children, these are the first two cases reported in the literature. [5] Only 1 patient had a fatal outcome related to B. vesicularis infection.

On the other hand, the antimicrobial regimen of choice for this pathogen is unknown. Antibiotic therapy should be directed according to susceptibility tests because resistance to different antibiotics has been observed; for example, resistance to colistin is a characteristic found in this genus. [23] Of the reports reviewed, we found that 26% (5/19) had resistance to colistin. In addition, resistance to the fluoroquinolone family has been detected due to mutations in the gyrA, gyrB, and parC genes, mainly in B. diminuta. [5] Susceptibility to colistin was not reported and resistance to fluoroquinolones was observed in both cases. Zhang et al. [17] suggested the use of piperacillin/tazobactam and third-generation cephalosporins as therapies; however, of the reports reviewed, 74% (14/19) showed resistance to ceftazidime and 53% (10/19) presented resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam. In both cases reported, piperacillin/tazobactam was started, but the patients did not show a favorable response with this antibiotic, although the case of B. aurantiaca was sensitive to piperacillin/tazobactam. It seems that antibiotic therapy with carbapenems has demonstrated greater effectiveness in infections caused by this pathogen. We did not find resistance to carbapenems in the pediatric population, and our cases responded favorably with meropenem. However, Scotta et al. [24] reported 3 Brevundimonas isolates in hospital wastewater carrying the gene encoding the VIM-13 metallobetalactamase (MBL) enzyme, indicating that this pathogen could represent a reservoir for the dissemination of MBL genes. A case of a B. diminuta carrier of MBL VIM-2 isolated in tissue culture in an adult patient has been reported. [25]

Conclusions

In conclusion, Brevundimonas species are emerging pathogens, of which little is known. The information available is mainly from the adult population, being scarce in the pediatric population. Therefore, it is important to review the clinical manifestations and the most appropriate antimicrobial regimen against this pathogen in immunocompromised children.

Author Contributions

AAB and JMA conceived the article. AAB, CCC, and JWL collected the data and drafted the article. MJP was responsible for the 16S rRNA gene sequencing. All authors were responsible for the critical review of the manuscript and read and approved its final version.

Funding

Internal funds were obtained from the Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima-Perú, for molecular typing.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of the Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño San Borja (INSN-SB), Lima-Perú (Reference No - AIIMS/IEC/2021/3546).

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients for the publication of this case report.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- Ryan, M.P.; Pembroke, J.T. Brevundimonas spp: Emerging global opportunistic pathogens. Virulence 2018, 9, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, P.; Vancanneyt, M.; Pot, B.; et al. Classification of Pseudomonas diminuta Leifson and Hugh 1954 and Pseudomonas vesicularis Büsing, Döll, and Freytag 1953 in Brevundimonas gen. nov. as Brevundimonas diminuta comb. nov. and Brevundimonas vesicularis comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994, 44, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LPSN—List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature. 2022. Available online: https://www.bacterio.net/genus/brevundimonas (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Tsubouchi, T.; Shimane, Y.; Usui, K.; et al. Brevundimonas abyssalis sp. nov., a dimorphic prosthecate bacterium isolated from deep-subsea floor sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2013, 63, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Y.; Andrade, R.A. Brevundimonas diminuta infections and its resistance to fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005, 55, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, N.; Karagol, B.S.; Kundak, A.A.; et al. Spectrum of Brevundimonas vesicularis infections in neonatal period: A case series at a tertiary referral center. Infection 2012, 40, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vegas, E.Z.; Nieves, B.; Araque, M.; et al. Outbreak of infection with Acinetobacter strain RUH 1139 in an intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006, 27, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatawadekar, S.M.; Sharma, J. Brevundimonas vesicularis bacteremia: A rare case report in a female infant. Indian J Med Microbiol 2011, 29, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhelman, R.A.; Humbert, J.R.; Santorelli, F.W. Pseudomonas vesicularis causing bacteremia in a child with sickle cell anemia. South Med J 1994, 87, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R.; Singh, A.; Mukherjee, R.; Sardar, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Mukherjee, S. Brevundimonas vesicularis: A new pathogen in newborn. J Pediatr Infect Dis 2010, 5, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menuet, M.; Bittar, F.; Stremler, N.; et al. First isolation of two colistin-resistant emerging pathogens, Brevundimonas diminuta and Ochrobactrum anthropi, in a woman with cystic fibrosis: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2008, 2, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofer, Y.; Zmira, S.; Amir, J. Brevundimonas vesicularis septic arthritis in an immunocompetent child. Eur J Pediatr 2007, 166, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, L.A.; Deboo, B.S.; Capers, E.L.; Pickett, M.J. Pseudomonas vesicularis from cervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 1978, 7, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bhatia, B.D. Brevundimonas septicemia: A rare infection with rare presentation. Indian Pediatr 2015, 52, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzon, C.; Nguyen, B.H. A rare case of peritonitis due to Brevundimonas vesicularis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2018, 8, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobha, K.L.; Ramachandra, L.; Gowrish, S.; Nagalakshmi, N. Brevundimonas diminuta causing urinary tract infection. WebmedCentral Microbiol 2013, 4, WMC004411. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Hsu, H.J.; Li, C.M. Brevundimonas vesicularis bacteremia resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ceftazidime in a tertiary hospital in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2012, 45, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Das, A.K.; Dudeja, M.; Tiwari, R.; Alam, S. Brevundimonas vesicularis bacteremia in a neonate: A rare case report. Natl J Integr Res Med 2013, 4, 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Haj Khalifa, A.; Bouzidi, H.; Sfar, M.T.; Kheder, M.; Ayadi, A. Bactériémie à Brevundimonas vesicularis chez un nourrisson atteint de la maladie de Pompe. Med Mal Infect 2012, 42, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, N.; Karagol, B.S.; Dursun, A.; Okumus, N.; Tanir, G.; Zenciroglu, A. A premature neonate with early-onset neonatal sepsis owing to Brevundimonas vesicularis complicated by persistent meningitis and lymphadenopathy. Paediatr Int Child Health 2012, 32, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Das, A.; Sen, M.; Sharma, M. Brevundimonas diminuta infection in a case of nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2017, 60, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.E.V.; Parra, J.C.; López, C.E.M.; Marcos, M.C.; Romero, I.S.; Forteza, A. First report of Brevundimonas aurantiaca human infection: Infective endocarditis on aortic bioprostheses and supracoronary aortic graft acquired by water dispenser of domestic refrigerator. Int J Infect Dis 2022, 122, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffineur, K.; Janssens, M.; Charlier, J.; Avesani, V.; Wauters, G.; Delmée, M. Biochemical and susceptibility tests useful for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative rods. J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotta, C.; Juan, C.; Cabot, G.; et al. Environmental microbiota represents a natural reservoir for dissemination of clinically relevant metallo-beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 5376–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuzara, M.N.; Barberis, C.M.; Rodríguez, C.H.; Famiglietti, A.M.; Ramirez, M.S.; Vay, C.A. First report of an extensively drug-resistant VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Brevundimonas diminuta clinical isolate. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 2830–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© GERMS 2023.