Introduction

Botulism is a rare and life-threatening intoxication with an exo-neurotoxin produced by

Clostridium botulinum. The bacteria can be isolated from soil, fruits, vegetables, seafood or improperly-stored food [

1,

2,

3].

Human botulism usually occurs when people ingest food contaminated with preformed botulinum neurotoxin (foodborne botulism) or when

Clostridium spores get into a wound in which it can germinate and produce the toxin (wound botulism). Through intact skin, the bacteria or the toxin cannot enter the body [

2].

Once it has entered the vascular system, the botulinum neurotoxin travels to the presynaptic nerve terminal of the voluntary motor and autonomic neuromuscular junctions where it causes an inhibition of the acetylcholine release. The result is a descending symmetrical flaccid paralysis due to the inhibition of muscle contraction and cranial nerve palsies, having a potential progression to respiratory failure and death [

1,

3]. The toxin does not affect the central nervous system [

3].

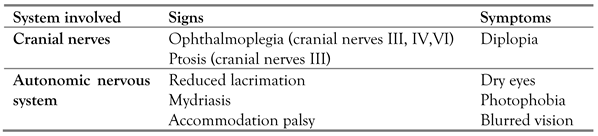

The classical presentation of botulism is generally characterized by bilateral cranial nerve palsies and bulbar symptoms that form the so-called “four Ds of botulism: diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia and dry-mouth”. Ophthalmic presentation includes ophthalmoplegia that is manifested by diplopia (cranial nerves paralysis, nerves III, IV, and VI), dry eyes, mydriasis, and photophobia [

4].

If one of the following criteria is met, then botulism can be confirmed in a symptomatic patient: 1) botulinum neurotoxin in serum, stool, or gastric fluid; 2) botulinum neurotoxin-producing species of

Clostridium (i.e.,

C. botulinum,

C. baratii, or

C. butyricum) in a stool or wound culture; or 3) botulinum neurotoxin in food consumed by a symptomatic person [

3]. The gold standard test for identifying botulinum toxin is the mouse bioassay which is also the only USA Food and Drug Administration approved method for laboratory confirmation of botulism. Timely administration of the only specific treatment, the botulinum antitoxin, reduces the extent and severity of the disease. The recovery is due to new nerve terminals formation which can take weeks to months to happen [

1].

National surveillance programs reported a relatively stable number of botulism cases between 2013 and 2015 (the last known report), most cases in Eastern Europe. In 2014, Romania reported the highest numbers of cases in the European Union (31 cases) and the highest rate (0.15 cases per 100 000 population) [

5].

Nowadays, there is still an important rate of mortality from botulism, dropping from over 60% before the 1950s to 3% in cases in the USA during the 1975-2009 interval. The mortality rate for foodborne botulism is higher, being estimated to 7.1% [

2].

The purpose of this paper is to advise clinicians on the potential differential diagnosis of botulism. Two patients presented with similar manifestations, two years apart, and required a complex, multidisciplinary approach. The awareness towards the disease, from the ophthalmology specialist, proved to be the most important part of the diagnosis process, considering that the first manifestations of the disease appeared in the ophthalmic spectrum.

Case report no. 1

A 19-year-old man presented to the Emergency Room of our Ophthalmology Department from the County Emergency Hospital of Cluj-Napoca, with the complaint of a painless near vision disorder (blurred vision) that had started a day prior. He also noted an accompanying dry-mouth (xerostomia) and dysphagia for solid food. The patient stated his symptoms started the morning after he had had a tattoo done on the right side of his neck. The tattoo had been made without proper aseptic technique and conditions regarding a sterile environment, including needles and ink storage. There were no signs of skin infection on the tattoo.

His medical history recorded headaches and dizziness with normal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), four years prior to the current admission. The patient also mentioned transient paresthesia in his right arm in the last two years without being further investigated at that point. The patient was a chronic smoker. He denied the consumption of any drugs. He was not on any regular medications.

The ophthalmological assessment revealed: best corrected vision acuity on both eyes (+1.00 sph) 20/20, right eye anisocoria (mydriasis), bilateral accommodation palsy and the same refractive status before and after cycloplegia (+1.50 sph). He also had a very poor bilateral pupillary light reflex (direct and consensual), an affected right eye chromatic perception, with mild dyschromatopsia (red color desaturation) and a normal ocular motility exam and fundus aspect on both eyes. His visual field (30-2 and 10-2, HFA II) had low reliability for the right eye and a paracentral scotoma for the left eye.

Dyschromatopsia in the right eye, paracentral scotoma in left eye, and normal optic disc prompted the diagnosis of bilateral optic retrobulbar neuropathy. The patient history pointed to a few possible etiologies: toxic (tattoo ink) or demyelinating (multiple sclerosis) because of his past right arm transient paresthesia, headaches and dizziness. Lyme disease was also considered for a possible optic nerve pathology. Corticosteroids were initiated (methylprednisolone sodium, at 250 mg/day, i.v.), together with i.v. treatment with antibiotics to cover neuroborreliosis (ceftriaxone sodium, 2 g b.i.d.), but the symptoms only worsened.

The lab tests returned unremarkable, inflammation markers were normal (C reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fibrinogen), and infectious serological testing for HIV, hepatitis B, C, and Lyme disease were negative. Brain MRI did not find lesions specific for multiple sclerosis. Contrast MRI found no intracranial tumors to account for neurologic disorders.

After 72 hours, he developed a progressive dysphagia for liquid food, mild dysarthria and dysphonia, accompanied by fatigue and constipation. After 24 more hours, the patient started to present a mild limitation of abduction in both eyes with mild diplopia in the lateral gaze. The ear-nose-throat (ENT) consult performed for dysphonia and dysarthria excluded an infectious laryngopharyngitis. Neurological consult revealed the suspicion of botulism. On this basis, the patient was transferred to the Hospital for Infectious Diseases, and was administered 50 mL of botulinum ABE antitoxin. Blood tests confirmed the diagnosis, but the type of toxin was not reported. All the symptoms cleared within 4-5 weeks and no sequelae remained at 3 months follow-up.

An epidemiological investigation was launched to find out the source for botulinum contamination. Homemade ham consumed a few days prior to symptom onset was incriminated, with no other person being affected from those who had shared the same meal. The neck tattoo performed 24 hours before symptom onset was also regarded as a possibility.

Case report no 2

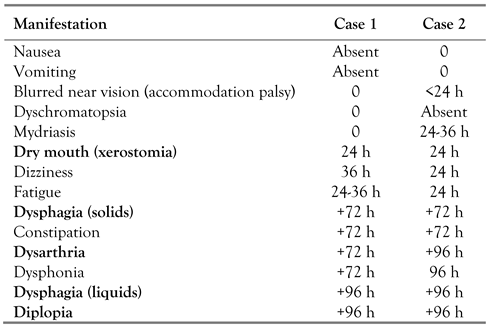

Another 19-year-old man presented to the Emergency Room from the County Emergency Hospital from Cluj-Napoca, almost 2 years after the first one, with the complaint of nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, dysphonia, dysarthria, dizziness, blurred near vision and diplopia, symptoms that had started mildly and progressed in intensity during the 6 days before presentation. General symptoms had started first, and ocular manifestation about 4 days later (

Table 1). An ophthalmology exam revealed bilateral areflexive mydriasis with accommodation palsy, palsy of cranial nerves III and VI with primary gaze diplopia. Fundus exam on both eyes was normal.

We started to make a targeted anamnesis searching for the “four Ds” which were present in this case, too: diplopia, dysphagia, dysarthria, dry mouth, accompanied by dysphonia, so we raised the suspicion of botulism. The neurologic consult revealed general hypotonia, lower limb motor deficit, coordination disorder.

He was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit and carefully monitored. The patient had favorable evolution after receiving ABE botulinum antitoxin, with symptom improvement.

The clinical presentation, unremarkable findings in paraclinical examinations, and rapid improvement after receiving ABE antitoxin all pleaded for botulism. A laboratory test for botulism is usually provided only after the therapy is administered based on clinical suspicion, and in this case the toxin was not identified (in mouse inoculation test).

After almost a week, the ophthalmology exam showed complete remission of diplopia with mild responsive bilateral mydriasis. No sequelae remained at 3 and 9 months follow-up.

In this case, on further questioning, our patient reported he had eaten some ham that was transported from another country (from a well-known source from which he had procured it before). No other epidemiological context was identified. There were no other members of the family who developed the same symptoms among those who had shared the same meal.

Discussion

Foodborne botulism case definitions include probable and confirmed cases. A probable case is defined as clinically compatible case with an epidemiologic link (e.g., ingestion of a home-canned food within the previous 48 hours). A confirmed case is defined as a clinically compatible case that is laboratory-confirmed or that occurs among persons who ate the same food as persons who have laboratory-confirmed botulism [

6]. Case no. 2 had no confirmation of the toxin. However, the diagnosis was presumed by clinical response to antitoxin immunoglobulin.

In 56% of cases, botulism has a systemic manifestation at the onset of the disease. Also, in 33% of cases, the symptoms start with both ophthalmic and systemic manifestations, and in only 11% of cases the ophthalmic manifestations occur first. More often, these ophthalmic manifestations include blurred vision followed by ptosis, in a symmetric pattern [

4].

Table 1 summarizes ocular manifestations of botulism.

Khakshoor et al. investigated 18 patients with foodborne botulism and identified the presence of blurred near vision and impaired accommodation in all patients. Overall, 94% of them experienced blurred distant vision, and 44% experienced diplopia. Regarding non-ophthalmological symptoms, the most common was dry mouth (100%), followed by constipation (83%), dysphagia (72%), nausea, vomiting or diarrhea and abdominal cramps; 50% of them experienced fatigue [

7]. In foodborne botulism, the gastrointestinal symptoms are common, although about 30% of patients may not present them at all. These symptoms may often precede the neurological toxidrome, even if they can develop at the same time [

5]. Depending on the amount of absorbed botulinum neurotoxin, the symptom’s onset varies typically from 2 to 36 hours (however it may be up to 8 days) [

8].

The two cases presented with very similar findings and had similar evolution.

Table 2 summarizes the general and ocular manifestations and the timeline for each of them, starting at time 0 hours, the clinical onset.

Regarding our first case, a toxic etiology (ink toxicity from the tattoo) for the retrobulbar optic neuropathy had to be ruled out. There is no reference to optic neuropathy as a feature of botulism; on the contrary, an article by Jedelhauser (1985) about botulism-related ocular manifestations in six cases states that none had any optic nerve lesion [

9]. The pathogenesis of botulism, interfering with cholinergic neurotransmission in motor and parasympathetic nerves, would seem to preclude involvement of the sensory functions of the optic nerve. Dyschromatopsia and visual field anomalies, usually associated with optic nerve involvement, appearing together with more specific botulism symptoms, and resolving after antitoxin administration, prompt us to report what may be the first case of botulism-related optic retrobulbar neuropathy.

Regarding some association between the tattoo and botulism contamination from the wound (tattoo that had been made without a proper aseptic technique and conditions for a sterile environment, including needles and ink storage; the eye on the same side was affected first), we had no real reasons to believe that this was the path through which the toxin entered the body. The fact that the tattoo was very recent, one day prior to symptom onset, and not clinically infected would seem to make wound botulism unlikely. Even though the literature referencing tattoo botulism is scarce, there have been reports in the United States of America of an increased number of cases of wound botulism following subcutaneous injection of black tar heroin (known colloquially as “skin popping”) [

8].

In both our reported cases, the presumed source of toxin was a piece of ham ingested a few days before the onset of symptomatology. In these two cases of foodborne botulism, our patients were the only persons from those who shared the same meal who developed symptoms. The food item may not be uniformly affected, so this aspect does not rule out this source of intoxication.

Regarding our second patient, the Miller Fisher syndrome (a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome) and myasthenia gravis were taken into consideration as differential diagnosis as they have symptoms and signs that overlap with botulism. Data from recent literature and case series revealed that botulism is commonly misdiagnosed as one of these two neurological diseases [

1,

4].

Miller Fisher syndrome is clinically represented by a well-known triad of limb ataxia, areflexia and ophthalmoplegia, also having a variable cranial nerve and extremity involvement [

4]. Our patient’s lumbar puncture and electroneuromyography showed normal findings.

Antibiotics have no effect on botulism treatment. The botulinum antitoxin is the standard of treatment as it interacts by neutralizing the toxin molecules before binding to the nerve endings, thus limiting the progression of paralysis [

4]. Supportive care is also required in these patients [

1].

In order to minimize the nerve damage and also the disease severity, it is important to administer botulinum antitoxin as soon as possible after symptom onset, ideally within 24 hours. There is no need to wait for the results of laboratory testing as the administration of the antitoxin is time dependent and must be sustained by the high clinical suspicion of botulism [

3].

The botulinum neurotoxin was detectable in our first patient’s blood after more than 7 days after the presumed moment of infection. This late detectability of the toxin in the patient’s body is a strong argument to initiate the antitoxin therapy even after the first 24-72 hours since onset as data reveals. From the data available to date, the ingested neurotoxin detectability in serum or feces can pe proved in 40 to 44% of cases within the first 3 days after toxin ingestion and in 15 to 23% of cases after 3 days [

10].

The second patient was given antitoxin the next day after the ophthalmologist raised the suspicion of botulism, at approximately one week after the onset. For the latter, the botulinum toxin was not identified. Both patients responded promptly to treatment with the remission of symptoms.

In both cases, clinical suspicion of botulism was raised based on the ocular manifestations: blurred vison (due to accommodation palsy), diplopia (due to extraocular muscle palsy) and then associated with the other “3 D`s”: dry-mouth, dysphagia, dysarthria.

Conclusions

Although a rare disease, botulism must be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute onset of neuro-ophthalmological damage with cranial nerve palsies (“bulbar symptoms”) and suggestive affected autonomic and peripheral nervous system.

Being a real public health emergency due to its life-threatening tendency, clinicians must pay attention to its many distinct initial clinical presentations that botulism can have.

The suspicion of botulism can be raised by its clinical presentation and the ophthalmologists play a key role in avoiding diagnostic delay and the risk of serious consequences. Clinical awareness of the “four Ds”, diplopia, dysphagia, dysarthria, and dry mouth, may prevent permanent paralytic damage and even the death of the patient.