Abstract

Introduction: Infectious diseases constitute a significant problem globally and healthcare professionals (HCP) show suboptimal vaccination rates. We aimed to evaluate the determinants affecting vaccination against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 among medical students in Cyprus. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study based on a self-reported, anonymous questionnaire that was sent to all medical students of two Medical Schools in the Republic of Cyprus. Results: Among 266 respondents, 50.8% had been vaccinated against influenza in the past and 20.1% in 2020-21. The majority believed that influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are safe and effective. Regarding vaccination in Cyprus, 41.3% did not know the current recommendations and a higher proportion of preclinical students replied incorrectly, compared to clinical students. Slightly over half (56.4%) considered themselves adequately informed about influenza vaccination, with more clinical students appearing confident (p=0.068). An overwhelming 71.2% were concerned about contracting SARS-CoV-2, compared to 25.4% with regards to influenza. Up to 76.8% considered themselves adequately informed about SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, with significantly more clinical students being confident (p<0.001). Although more preclinical students appeared hesitant, most students had either been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 (49.4%) or would be as soon as possible (32.1%). Vaccination refusal was 2.3%, a group comprised entirely of preclinical students. Conclusions: Our study provides relevant and actionable information about differences in attitudes and perceptions between clinical and preclinical medical students regarding vaccination against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 and highlights the importance of organized, systemic efforts to increase vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Influenza causes epidemics every year and is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable disease (VPD)-associated morbidity and mortality, accounting for at least 40,000 deaths in the European Union (EU) annually [1]. Despite the required annual administration and moderate effectiveness that varies between seasons, vaccination remains the most affordable and accessible means of prevention [1,2]. Although annual vaccination for healthcare professionals (HCP) is recommended, coverage in many EU countries remains low [1,3].

The rationale for vaccinating HCP lies beyond the protection of vulnerable populations, as it also ensures uninterrupted operation of medical services and provision of healthcare [1,2]. Nevertheless, most medical schools merely recommend vaccination and or guide students appropriately, as influenza vaccine uptake rarely exceeds 40% in these populations [1,4]. These shortcomings are often encountered due to the low perceived risk from the disease, as well as misconceptions regarding vaccine significance, effectiveness and safety [5,6,7,8].

Communication and education are crucial in vaccine acceptance among medical students and HCP [9,10]. In Europe, surveys frequently show high acceptance rates and positive attitudes towards vaccination but suboptimal coverage and compliance, mainly due to lack of incentives and accessibility [5,6,7,8].

Influenza can present with symptoms similar to coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a novel respiratory infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [11]. COVID-19 has resulted in significant mortality and morbidity, leading to one of the largest pandemics in human history [11]. Recent development of vaccines has raised the need to ensure widespread access, especially among high-risk groups [11].

Young adults, such as students, may have a role in disease spread due to their high social activity, increased mobility, and regular contact with patients [6]. Additionally, young and healthy individuals may be asymptomatic carriers, acting as a hidden reservoir for respiratory viruses. Achieving high vaccination coverage among medical students will increase coverage among HCP in the future, as previous vaccination is an important vaccination determinant [12].

Our aim is to evaluate determinants of vaccination against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 in medical students in the Republic of Cyprus, by assessing current vaccination status, perceptions, and attitudes towards vaccination among medical students. We hypothesized that clinical students have better knowledge and more favorable attitudes towards vaccination.

Methods

For this cross-sectional study, an original questionnaire in English was used (Appendix). The questionnaire was pilot tested with six persons and was available online as a Google forms© survey that could be completed only once. It was comprised of five demographic questions requesting gender, age, nationality, university, and year of study, as well as 28 multiple choice questions about knowledge of recommendations, attitudes, and perceptions of the two vaccines.

The questionnaire was distributed and completed in March-April 2021. All students of two out of three Medical Schools in the Republic of Cyprus (European University Cyprus, EUC and University of Cyprus, UCY) were invited to complete it through university emails. The 2 participating schools are 6-year medical schools, where years 1-3 are preclinical and years 4-6 are clinical which primarily consist of clinical clerkships. Public health, physiology, pathophysiology, clinical microbiology and infectious diseases, are included early in the medical school curricula. Thus, medical students are expected to understand the importance of vaccination before entering the clinical part of their studies. During the study period, 4 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 (Vaxzevria/Astrazeneca, Comirnaty/Pfizer, Spikevax/Moderna, Janssen) were licensed and used in the Republic of Cyprus and more than 200,000 doses were administered (including more than 57,000 persons fully vaccinated) among a total population of 875,000 [13].

The total number of students in the two medical schools when the questionnaire was distributed was 826. For 826 students, with a 5% margin error and 95% confidence interval, minimum sample size for statistical significance is 263. We defined hesitancy as the percentage of students that wish to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination after a few months or a year, instead of when the vaccine is available, and refusal as the percentage of students that wish to never receive vaccination. Associations of knowledge and attitudes with participants’ clinical exposure (years 1-3 and 4-6) and perceptions were assessed using the Chi-square test (χ²). Responses "Agree/Slightly agree” were grouped as "Yes”, "Disagree/Slightly disagree” as "No” and "Neutral/I don’t know” as "I don’t know”. Statistical significance was set at 5% significance level (p<0.05). Data were processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (IBM Corp, USA) and Microsoft Office Excel version 16.47 for Mac, (Microsoft Press, USA).

Permission was granted from the University Research Committees and the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (ΕΕΒΚ ΠΚ 2021.01.46, February 22nd, 2021). Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants consented to providing their information and were ensured that any personally identifiable information would not be saved.

Results

Participants and demographics

During the study period, 266 students completed the questionnaire (32.2% response rate). One response was not included in analysis, as the participant did not state their level of clinical exposure. Most participants were female (62.8%); gender was not significantly associated with knowledge, attitudes, or perceptions. Median and mean age were 22 and 22.6 years respectively (σ=3.42). Almost half of the students were Greek nationals (42.5%), followed by Cypriot nationals (30.5%) and other European and non-European nationals (27%). The majority were studying at EUC (73.2%) and 60.7% of participants were clinical students.

Influenza

Personal history regarding influenza vaccination

Half (50.8%) of respondents reported being vaccinated against influenza at some point in the past and 40.9% had never been vaccinated. The majority (78.8%) did not receive an influenza vaccine in 2020-2021. There was no significant difference between clinical and preclinical students regarding past vaccination (Table 1).

Table 1.

Personal history regarding influenza vaccination, comparison between clinical and preclinical students.

Perceptions of influenza vaccination

Of unvaccinated students, 44.3% believed that it was not necessary, 20.7% chose convenience/difficulty to access the vaccine as the main reason for not seeking vaccination and 31% chose other reasons (Table 2). The vast majority (91.6%) considered influenza vaccination safe (96.3% clinical, 84.5% preclinical, p=0.001) and 89.8% considered it effective (83.7% clinical, 93.8% preclinical, p=0.025). Almost half (47%) of respondents believed that their institution recommends influenza vaccination and 41.3% did not know the current recommendations. Of the clinical students, 49.1% said "Yes” compared to 43.7% of the preclinical students (p=0.012). Of those that replied "Yes”, 56.5% had been vaccinated against influenza at least once in the past. Less than half (45.8%) of the students replied "No” when asked if influenza vaccination is mandatory for medical students in Cyprus, with significantly more clinical students replying correctly than preclinical students (64.2% compared to 17.5%, p<0.001). The majority of preclinical students (67%) did not know if vaccination was mandatory, compared to 32.7% of clinical students. Slightly over half (56.4%) of students considered themselves adequately informed about influenza vaccination, with more clinical students replying positively (61.9% and 48.1% respectively, p=0.068). Of the students that considered themselves adequately informed, 39.7% did not know if influenza vaccination is mandatory for medical students in Cyprus.

Table 2.

Perceptions of influenza vaccination, comparison between clinical and preclinical students.

Attitudes towards influenza vaccination

A quarter of the students (25.4%) agreed/slightly agreed with being concerned about contracting influenza, while 36.4% disagreed/slightly disagreed. When commenting on the statement "it is not convenient to be vaccinated every year”, 45.3% disagreed/slightly disagreed. The majority (57%) chose disagree/slightly disagree with the statement "I intend to be vaccinated but can’t find the time”, while 20.9% agreed/slightly agreed. When asked if they have easy access to an influenza vaccine, 46.8% selected agree/slightly agree, while 25.9% disagreed/slightly disagreed. Most students (77.4%) would get the vaccine if their institution offered free annual vaccination. No significant association between clinical exposure and vaccination intention was observed. Of students that replied positively, 34.6% had never been vaccinated before. Attitudes towards influenza vaccination are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Attitudes towards influenza vaccination, comparison between clinical and preclinical students.

SARS-COV-2

Perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Respondents that considered themselves at an increased risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 (47%) were almost equal to those that didn’t (46.6%). Significantly more clinical students (65.6%) considered themselves at an increased risk compared to preclinical students (18.3%, p<0.001). More clinical students appeared concerned about contracting SARS-CoV-2, 75% of which replied with agree/slightly compared to 65.4% of preclinical students (p=0.045). Concerning SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, 77.7% of the respondents agreed/slightly agreed that vaccination is effective. Most (76.4%) agreed/slightly agreed that vaccination is safe, while 4.9% disagreed/slightly disagreed. Preclinical students were more likely to believe that vaccination is not safe or effective (3.8% and 9.8% respectively) compared to clinical students (1.9% and 1.2%, respectively; p=0.012 and p=0.276, respectively). Nearly three quarters (76.8%) considered themselves adequately informed about SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (clinical, 84.5% vs preclinical, 64.7%; p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, comparison between clinical and preclinical students.

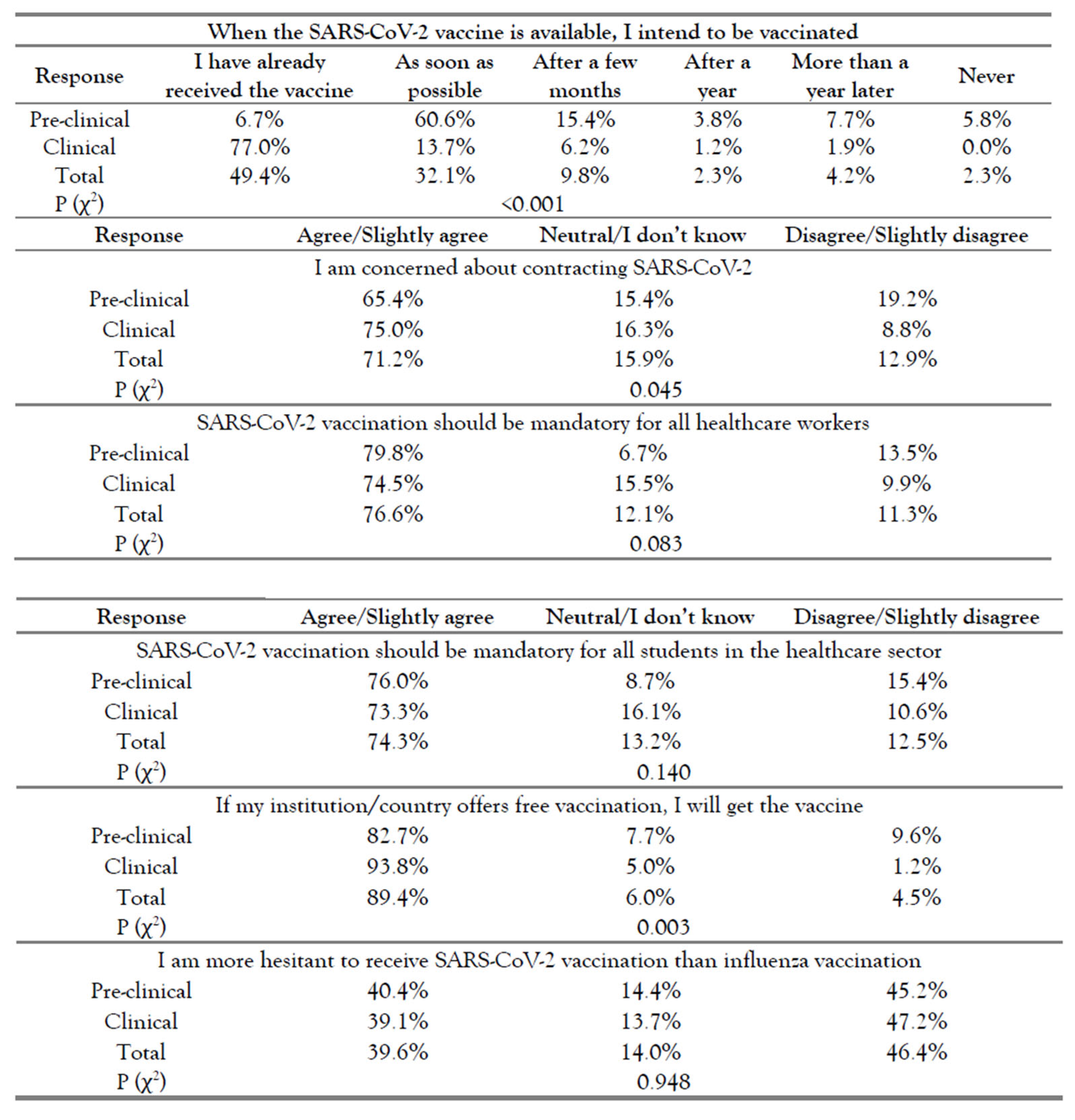

Attitudes towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

When asked about intention to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, 49.4% had already received a vaccine, 32.1% would get vaccinated as soon as possible, 14% would wait for some time and 2.3% would never get it (Table 5). The vast majority (89.4%) agreed/slightly agreed that if their institution/country offered free vaccination, they would get the vaccine. More clinical students would participate in free vaccination (93.8%) compared to preclinical students (82.7%, p=0.003).

Table 5.

Attitudes towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, comparison between clinical and preclinical students.

Discussion

Reasons for high acceptance of the influenza vaccine in previous studies were self-protection, recommendation to vaccinate, positive attitudes towards vaccination, patient protection, professional ethics, and free vaccination [6,7,8]. Reasons for vaccine refusal were inconvenience, forgetfulness, side-effects concerns, perceiving vaccination as unnecessary, vaccine cost and lack of knowledge [6,7,8,14].

Reported vaccination coverage for influenza ranges from 4.7% to 58.1% [6]. In accordance, our study showed a 50.6% past vaccination rate overall and a disappointingly low rate of 20.1% in 2020-2021. However, this proportion is comparable to the reported vaccination coverage for influenza (31.8%) among healthcare workers in Cyprus [15]. Possible explanations other than low-risk perception could be that influenza was not expected to be so prominent, that our students did not expect significant clinical exposure, or had limited accessibility to vaccination sites due to COVID-19 restrictions. Clinical students have been described as more likely to be vaccinated than preclinical students, [7,8] although we did not observe a significant difference.

Other studies found a similar correlation between clinical exposure and knowledge or attitudes towards vaccination [6,7,8,16]. More clinical students in our sample showed positive attitudes and were informed regarding the current recommendations. We also observed that more clinical students were confident in their knowledge and were not hesitant to receive vaccination. These findings are in line with Saftenburg et al., that report correlation between semester of studies and knowledge about national vaccination recommendations, [16] as well as Hernández-García et al., where clinical students had better knowledge concerning influenza [17].

More than half (54.2%) of the students replied incorrectly when asked if influenza vaccination is mandatory in Cyprus (82.5% of preclinical, 35.8% of clinical students, p<0.001) and 41.5% didn’t know if it was recommended by their institution. When asked if they considered themselves adequately informed about influenza vaccination, only 56.4% of students replied positively. This is in accordance with the results by Kernéis et al., who reported significant knowledge gaps and a need to clarify recommendations [18].

A limited number of studies focused on SARS-CoV-2 vaccination determinants in medical students [19,20,21,22]. Almost all students in the study by Lucia et al. had positive attitudes towards vaccination and agreed they were likely to be exposed to COVID-19 [19]. In Saied et al., 90.5% perceived the importance of vaccination and in Szmyd et al., more than 90% of medical students wanted to get vaccinated [20,22]. In our study, 89.4% replied positively to "If my Institution/country offers free vaccination, I will get the vaccine”.

In the literature, the percentage of students characterized as hesitant was 13.9-46% [20,21]. Similarly, there was marked hesitancy in our sample (16.3%). Saied et al. reported that most of the students (71%) accepted the vaccine but would postpone it for some time, and Lucia et al. reported that 23% of medical students were unwilling to be vaccinated immediately upon FDA approval [19,20]. Among our students, more preclinical students appeared hesitant than clinical students (63.7% vs 90.7%; p<0.001). SARS-CoV-2 vaccination had already been offered to clinical students at the time of questionnaire completion, which explains the difference in the number of vaccinated students (77% clinical, 6.7% preclinical, p<0.001). Saied et al. reported an interestingly lower percentage (13%) of students that intended to receive the vaccine "as soon as possible” compared to 32.1% in our study and 76.3% by Szmyd et al [20,22]. This proportion could have been ~81.5% in our study, if 49.4% hadn’t already received the vaccine. Willingness to get vaccinated as soon as possible was amplified by fear of passing on the virus to relatives, fear of infection and disease complications, as well as the year of study. Vaccination refusal was 2.3%, which is markedly lower compared to 13.9% – 16% in the literature [20,22]. In previous studies, the most reported factor affecting SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy was fear of side and adverse effects [19,20,21,22].

As with influenza, more clinical students have positive attitudes towards vaccination, are confident with their knowledge and are not hesitant as often as preclinical students. In agreement with previous observations, [5,18] most of our students (76.8%) consider themselves adequately informed concerning SARS-CoV-2, with significantly more clinical students (84.5%) replying positively compared to 64.7% of preclinical students (p<0.001). This is also in line with a previous survey among university students in Cyprus before vaccines became available, where postgraduate students exhibited higher levels of knowledge related to COVID-19 characteristics and prevention measures [5]. Saied et al. reported that their students perceived themselves at elevated risk to contract COVID-19 (77.6%), which is notably larger compared to our results (47%) [20]. This is in accordance with Wicker et al., who suggested that students may be inaccurate when assessing their risk to contract specific VPDs [8]. However, a high percentage of students in our sample had already been vaccinated and may not have been exposed to patients due to remote learning.

We observed that more students had positive attitudes towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination compared to influenza and more were concerned about contracting SARS-CoV-2 (71.2%) than influenza (25.4%). Most students (76.8%) considered themselves adequately informed about SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, but fewer (56.6%) replied similarly for influenza, despite the latter being discussed early and repeatedly in medical education. This could be explained by the publicity of the pandemic, the increased risk perception of SARS-CoV-2 or the low risk perception of influenza. In our sample, only 77.1% would participate in free annual influenza vaccination, compared to 89.1% that would participate in SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Commenting on "I think it is important to protect my friends and family from the risk of infection” 98.1% replied positively for SARS-CoV-2, compared to 88.7% for influenza, further indicating their perception of SARS-CoV-2 as a greater threat.

Easy access to the vaccine is not always offered to medical students, even during clinical training [6]. Organizational barriers, such as vaccination not being offered, have been considered possible factors in hindering vaccination [6,17,23,24]. This could partly explain the intention-behavior gap that has been observed in the literature [6]. In our study, 20.6% of the students chose convenience and accessibility as their main reason for not taking the influenza vaccine. Only 46.8% of students indicated that they have easy access to an influenza vaccine, while 77.4% would get the vaccine if it was offered for free by the institution they attend. More than a third of those students had never been vaccinated against influenza. Among our clinical students, 77% had been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 but only 21.3% had been vaccinated against influenza for 2020-2021, at the time of questionnaire completion. This may be attributed to their increased risk perception of SARS-CoV-2, but also to vaccination being organized and directly offered for free by the University. Our data support the theory that lecture-based education alone, may not have the desired effects when it comes to vaccination [18]. Specific targeted but easy to integrate interventions, such as hands-on or case-based learning, have demonstrated a positive shift in attitudes towards vaccination [18,23,25]. Specifically, the invitation from the University and a specific training about influenza vaccination have been shown to improve acceptance of vaccination [18,23,25].

Certain limitations in our study should be acknowledged. Two out of three Medical Schools in Cyprus participated in this study, which may affect its generalizability. The subject’s sensitivity may introduce bias, especially if students believe that vaccination is mandatory. The aim of our study was to identify attitudes and perceptions; future studies should examine vaccination determinants among students in depth, in order to identify opportune occasions to enhance vaccination. Additionally, perceptions and attitudes were not included in a scoring system, thus limiting the ability for comparisons.

Conclusions

The current study showed that medical students, especially preclinical students, have significant knowledge gaps and are more likely to have misconceptions about influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. The importance of organized institutional efforts in increasing vaccination coverage is also highlighted. Education efforts on VPDs should be addressed during early medical training, to enhance motivation and produce favorable attitudes towards vaccination.

Author Contributions

Conception: ES, CT; Design: ES, APA, CT; Data acquisition: ES; Data analysis: ES, SAK, APA; Data interpretation: all authors; Drafting: all authors. Critical revision for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (ΕΕΒΚ ΠΚ2021.01.46 on the 22nd of February 2021) and the internal University Research Committees of the two participating Universities.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

ES would like to acknowledge the training and guidance she received by the Medical School of the European University Cyprus, as this study was part of her Medical Thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- Maltezou, H.C.; Poland, G.A. Vaccination policies for healthcare workers in Europe. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 4876–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.E.; Uyeki, T.M.; Broder, K.; et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010, 59, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/influenza-vaccination-coverage-rates-insufficient-across-eu-member-states (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Maltezou, H.C.; Theodoridou, K.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Theodoridou, M. Vaccination of healthcare workers: Is mandatory vaccination needed? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019, 18, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, N.; Tsioutis, C.; Kolokotroni, O.; et al. Gaps in knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 & COVID-19 among university students are associated with negative attitudes toward people with COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Cyprus. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 758030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, B.A.; Ruiter, R.A.; Wicker, S.; Chapman, G.; Kok, G. Medical students' attitude towards influenza vaccination. BMC Infect Dis. 2015, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milunic, S.L.; Quilty, J.F.; Super, D.M.; Noritz, G.H. Patterns of influenza vaccination among medical students. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, S.; Rabenau, H.F.; von Gierke, L.; François, G.; Hambach, R.; De Schryver, A. Hepatitis B and influenza vaccines: Important occupational vaccines differently perceived among medical students. Vaccine. 2013, 31, 5111–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, C.M.; Poland, G.A. Vaccine education spectrum disorder: The importance of incorporating psychological and cognitive models into vaccine education. Vaccine. 2011, 29, 6145–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmeyer, H.G.; Hayden, F.; Poland, G.; Buchholz, U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals-a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine. 2009, 27, 3935–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.G.; Lin, T.; Wang, P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowicz, R.; Wyszomirski, T.; Ciechanska, J.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and influenza vaccination of medical students in Warsaw, Strasbourg, and Teheran. Eur J Med Res. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Cyprus. 200,000 vaccinations administered in Cyprus until today. 2021.

- Betsch, C.; Wicker, S. E-health use, vaccination knowledge and perception of own risk: Drivers of vaccination uptake in medical students. Vaccine. 2012, 30, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, C.; Mazeri, S.; Karaiskakis, M.; et al. Exploring vaccination coverage and attitudes of health care workers towards influenza vaccine in Cyprus. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanftenberg, L.; Roggendorf, H.; Babucke, M.; et al. Medical students' knowledge and attitudes regarding vaccination against measles, influenza and HPV. An international multicenter study. J Prev Med Hyg. 2020, 61, E181–E185. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-García, I.; Domínguez, B.; González, R. Influenza vaccination rates and determinants among Spanish medical students. Vaccine. 2012, 31, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernéis, S.; Jacquet, C.; Bannay, A.; et al. Vaccine education of medical students: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Am J Prev Med. 2017, 53, e97–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021, 43, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saied, S.M.; Saied, E.M.; Kabbash, I.A.; Abdo, S.A.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 4280–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Nania, T.; Dellafiore, F.; Graffigna, G.; Caruso, R. 'Vaccine hesitancy' among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmyd, B.; Bartoszek, A.; Karuga, F.F.; Staniecka, K.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Medical students and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: Attitude and behaviors. Vaccines. 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, N.; Kavanagh, M.; Swanberg, S. Improvement in attitudes toward influenza vaccination in medical students following an integrated curricular intervention. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, T.R.; Dellit, T.H.; Hebden, J.; Sama, D.; Cuny, J. Factors associated with increased healthcare worker influenza vaccination rates: Results from a national survey of university hospitals and medical centers. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallone, M.S.; Gallone, M.F.; Cappelli, M.G.; et al. Medical students' attitude toward influenza vaccination: Results of a survey in the University of Bari (Italy). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017, 13, 1937–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2022.