Abstract

Introduction: Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) manifests in a broad clinical spectrum. COVID-19 survivors report various symptoms up to several months after being infected. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome in Indonesia, the factors that influence the incidence, and the quality of life. Methods: This was a cross-sectional study with an online questionnaire conducted in January 2021. Inclusion criteria were: adult Indonesian citizens who had recovered from COVID-19, and were confirmed negative by RT-PCR of nasal swabs or had undergone an isolation period for a minimum of 14 days. Data analysis was performed by the Chi-square test, followed by multivariate analysis with the backward likelihood ratio method. Results: From a total of 385 respondents, 256 (66.5%) experienced persistent COVID-19 syndrome. The most prevalent symptoms were fatigue (29.4%), cough (15.5%), and muscle pain (11.2%). Of the five aspects of quality of life, the most commonly reported aspects were pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The risk of persistent COVID-19 syndrome was significantly higher in subjects with older age, comorbidities, higher clinical severity, previous treatment in hospital, presence of pneumonia, and those who had required oxygen therapy. In the multivariate analysis, the most influential factor for the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome was pneumonia (aOR 2.31, 95% CI 1.29-4.11, p<0.002). Conclusions: The prevalence of the persistent COVID-19 syndrome in Indonesia was high, which affects the quality of life of COVID-19 survivors. Pneumonia was the main factor that influenced the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome. Further research with a larger sample size and a longer study time is recommended to control COVID-19 and its impact on the health and quality of life of COVID-19 survivors.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) manifests in a broad clinical spectrum from asymptomatic to severe and critical [1]. The ACE2 receptors, widely expressed in the lungs, cardiovascular system, gut, kidneys, central nervous system, and adipose tissue, are involved in determining clinical signs and symptoms in COVID-19 [2]. ACE2 downregulation in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection also leads to increased production of cytokine/chemokine and cellular damage because of apoptosis and/or pyroptosis, as well as imbalance in the RAS system and increased levels of ACE and Ang II, thus causing multisystem inflammation [3].

Persistent COVID-19 syndrome is known to be similar to the post-viral syndrome found in previous human coronavirus diseases, where patients were reported to have experienced symptoms of fatigue, myalgia, and psychiatric disorders for up to 4 years after infection [4]. Pulmonary and bone radiological complications were seen in some SARS survivors at 15-years follow-up [5].

It was proposed that this phenomenon is caused by long-term tissue damage and unresolved inflammation [6]. Pulmonary radiological abnormalities (such as pulmonary scarring and fibrosis) and functional impairments (such as reduced lung diffusion capacity) were still reported in COVID-19 survivors three months after infection, which may explain persistent dyspnea due to an impaired gas exchange capacity of the lungs [7]. Structural and metabolic abnormalities in the brain had also been reported in COVID-19 survivors, which may explain persistent neurological symptoms such as memory loss, anosmia, and fatigue [8]. Radiological abnormalities in the heart and myocardial inflammation in COVID-19 survivors, although not yet accompanied by conclusive evidence, can explain other rare symptoms such as heart palpitation and chest pain [9]. In terms of unresolved inflammation, this was thought to be related to dysfunction of immune cells such as T cells, B cells, various autoantibodies against interferons, neutrophils, connective tissues, as well as lymphopenia occurring in SARS-CoV-2 infection. This condition causes a mechanism of autoimmunity and chronic hyperinflammation which causes the finding of COVID-19 patients who remained positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR, along with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, myalgia, or joint pain for up to several months [6].

A previous study showed that out of ten people, one reported symptoms for more than 4 weeks, and 1.5% to 2% still reported symptoms for more than 3 months [10]. Tenforde et al. [11]. reported that from 350 COVID-19 patients treated in the United States, only 39% had returned to their original health condition within 14 to 21 days of diagnosis [11]. In line with the United States report, Carfi et al. [12]. reported that from 143 COVID-19 patients in Italy, only 13% reported being free of symptoms after a mean of 60 days after the onset of symptoms [12]. The most common persistent symptoms are fatigue, dyspnea, cough, joint pain, and chest pain. Other symptoms are headache, muscle pain, palpitation, memory deficit, difficulty in concentration, and mental health disorders such as depression [11,12,13,14,15,16].

There has been no study that reported the persistent COVID-19 syndrome phenomenon in Indonesia. This study aimed to determine the clinical characteristics and quality of life of long-term sequelae of COVID-19 patients in Indonesia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted using an online questionnaire from 9 to 28 January 2021, during the first COVID-19 wave in Indonesia. The sampling was performed using the total sampling method. Inclusion criteria were Indonesian citizens over 18 years of age who were confirmed positive for COVID-19 based on reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from nasal swabs, and who had recovered from COVID-19 (were confirmed negative by RT-PCR from nasal swabs or had undergone mandated isolation period for a minimum of 14 days), and were willing to complete questionnaires online. Subjects with missing data subsets and lacking contact source data were excluded. Cases with fever, cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, headache, muscle pain, and fatigue are considered as mild COVID-19 while rapid breathing frequency and dyspnea with peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 90-93% are considered as a moderate case. A case with severe pneumonia and/or with requirement of oxygen therapy is considered as severe COVID-19 while a case with acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and/or septic shock is considered as a critical case.

Respondents completed the questionnaire containing identities, comorbidities, and the clinical symptoms experienced during and after recovery from COVID-19, adapted from Mandal et al. [17]. They also completed the Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) Scale [18] and the EQ-5D Questionnaire [19] for measuring the degree of disability from dyspnea and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The EQ-5D questionnaire consists of 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, each of which has the level of having no problems, some problems, and severe problems. The subjects were also asked about the Visual Analog Scale regarding health conditions that were perceived subjectively, with 0 being the worst health condition imaginable and 100 being the best health condition imaginable. All questionnaires used were translated to the Indonesian language. This study was performed using the snowball sampling technique. The online questionnaire was delivered through an electronic message broadcasting system within the Indonesian region. All data obtained from 9 to 28 January 2021 were then entered and verified for further statistical processing.

Subjects who still reported symptoms after recovering from COVID-19 for a minimum of two weeks after the negative RT-PCR result or after the completion of the 14 days isolation period were considered to have persistent COVID-19 syndrome. Duration of persistent COVID-19 syndrome was counted from the moment when the RT-PCR negative result came out or from the completion of the isolation period.

Descriptive and analytical analysis was then carried out. Bivariate analysis was conducted to determine whether there were significant differences in the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome in subjects with different variable categories. The bivariate analysis was performed using the Chi-square test with some modified variables to meet the criteria for the Chi-square test. Numerical data such as age and BMI were analyzed by T-test to compare means. Subjects were then separated into two groups with three months of persistent COVID-19 syndrome duration being the cut-off. Variables with p <0.250 in bivariate analysis were then analyzed in multivariate analysis using logistic regression with the backward likelihood ratio (LR) method. The multivariate analysis was conducted twice to determine demographic and clinical factors which influence the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome in subjects from both groups. Variables with a p value <0.250 from the table of bivariate analysis results were included, which were age, comorbidities, nutritional status, clinical severity, type of care, radiological finding, and oxygen therapy.

This research received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (Number: KET-158/UN2.F1/ ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020, dated 21 December 2020).

Results

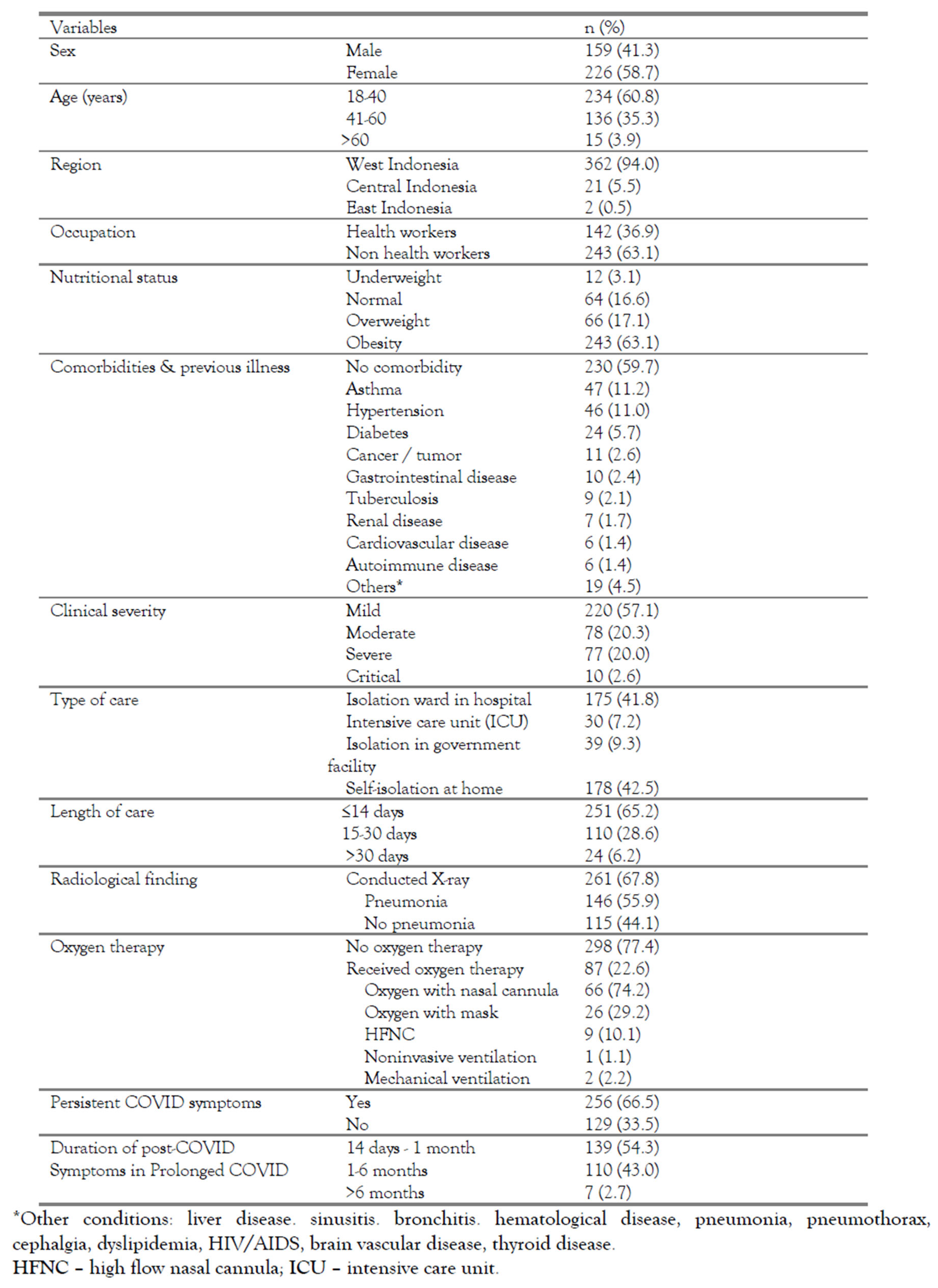

The total subjects of this study were 385 respondents, with their demographic and clinical characteristics shown in Table 1. Most of the subjects were female (58.7%), aged 18-40 years (60.8%), and lived in the west Indonesia region (94.0%). A total of 36.9% of subjects were healthcare workers. Nutritional status was dominated by obesity (63.1%). The most prevalent comorbidities were asthma (11.2%), hypertension (11.0%), and diabetes (5.7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects.

The majority of subjects (57.1%) experienced mild COVID-19. The most common types of care were isolation wards in hospitals (41.8%) and self-isolation at home (42.5%), with most patients (65.2%) being treated for periods up to 1-2 weeks. Among 261 subjects who had undergone chest X-rays, 146 (55.9%) had pneumonia. Oxygen therapy was given to 87 subjects (22.6%), mainly by nasal cannula (74.2%). The prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, as determined by the criteria described before, were found in 256 (66.5%) subjects. A total of 16.8% of subjects with COVID-19 reported persistent symptoms for more than 3 months.

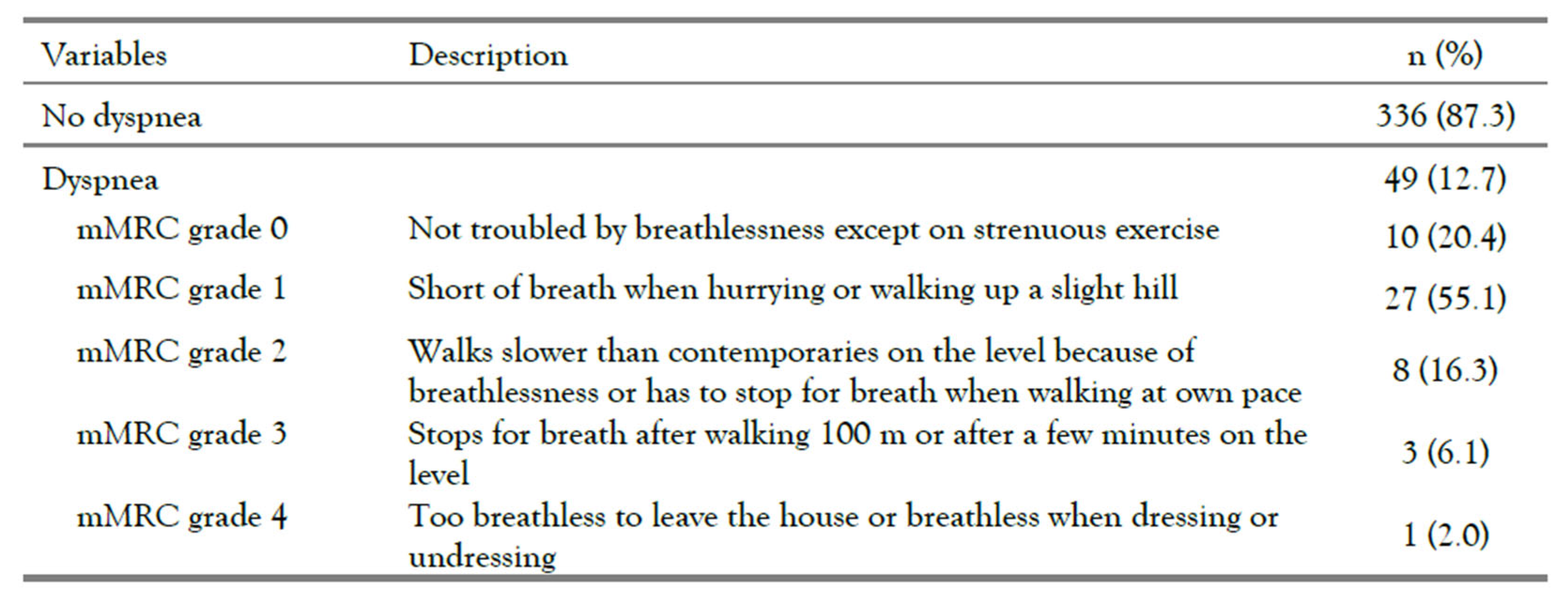

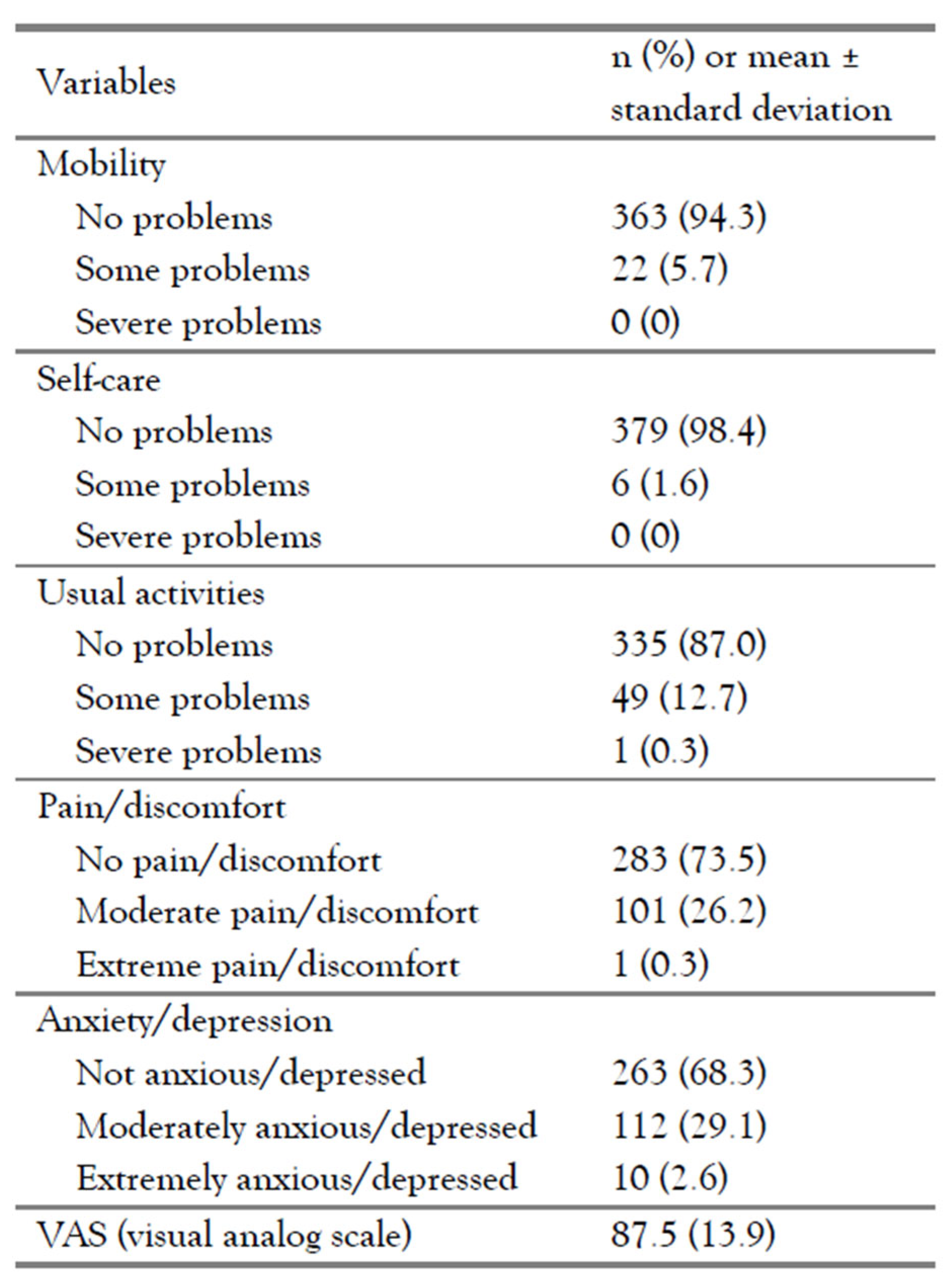

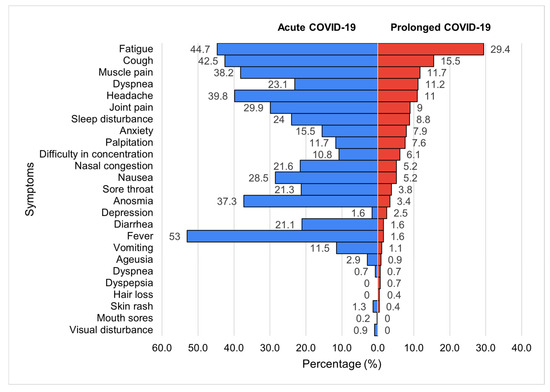

The clinical symptoms reported are listed in Figure 1. Fever was the most frequent symptom during acute COVID-19 (53.0%), but only in 1.9% of cases persistent fever was reported following COVID-19 recovery. Meanwhile, fatigue (29.4%) was the most common persistent symptom, followed by cough (15.5%), muscle pain (11.7%), dyspnea (11.2%), and headache (11%). The mMRC scale scores are reported as shown in Table 2 while the quality of life assessment results are displayed in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Clinical symptoms in acute COVID-19 and prolonged COVID-19 (n=385).

Table 2.

Dyspnea mMRC scale (post-COVID-19).

Table 3.

Quality of life.

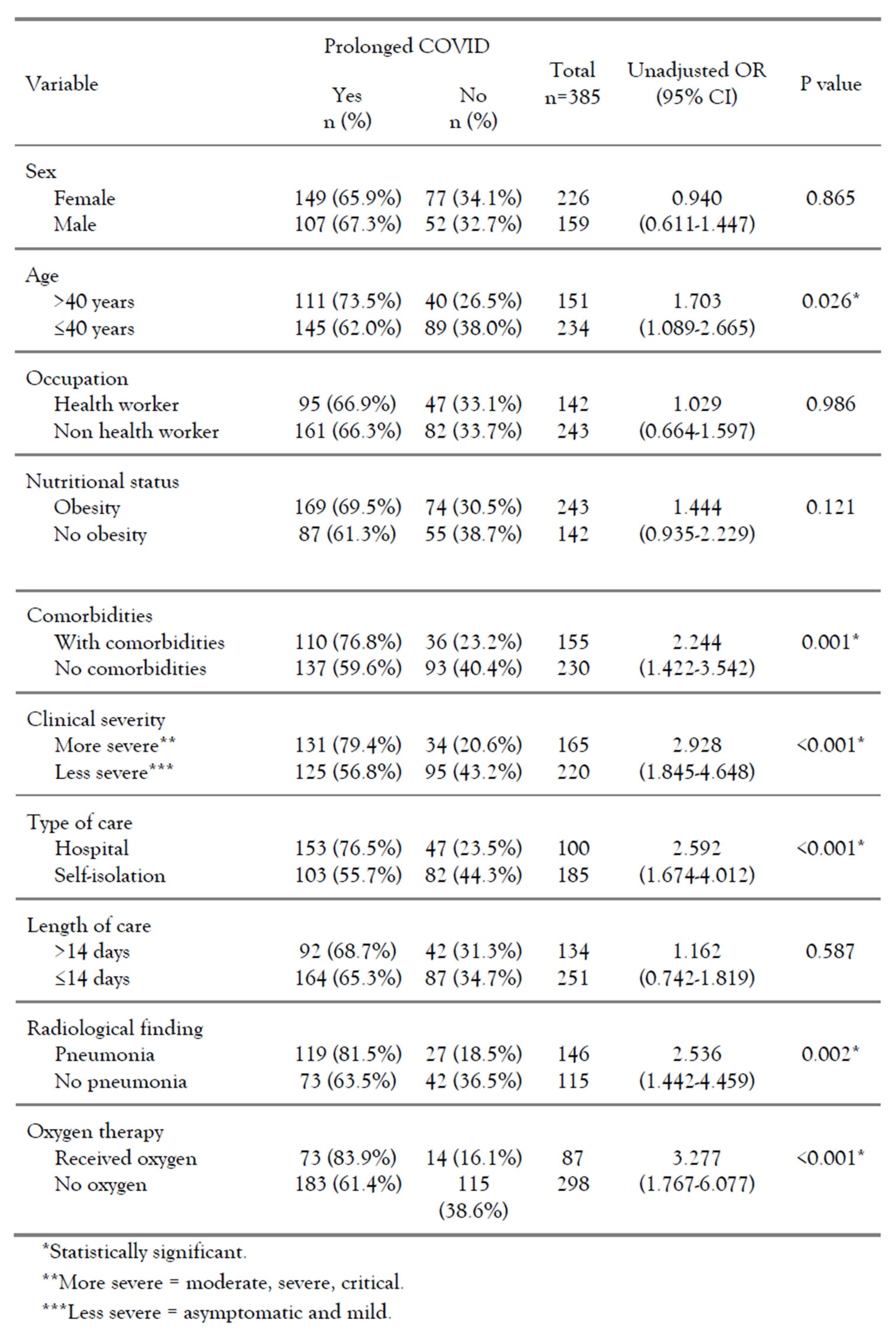

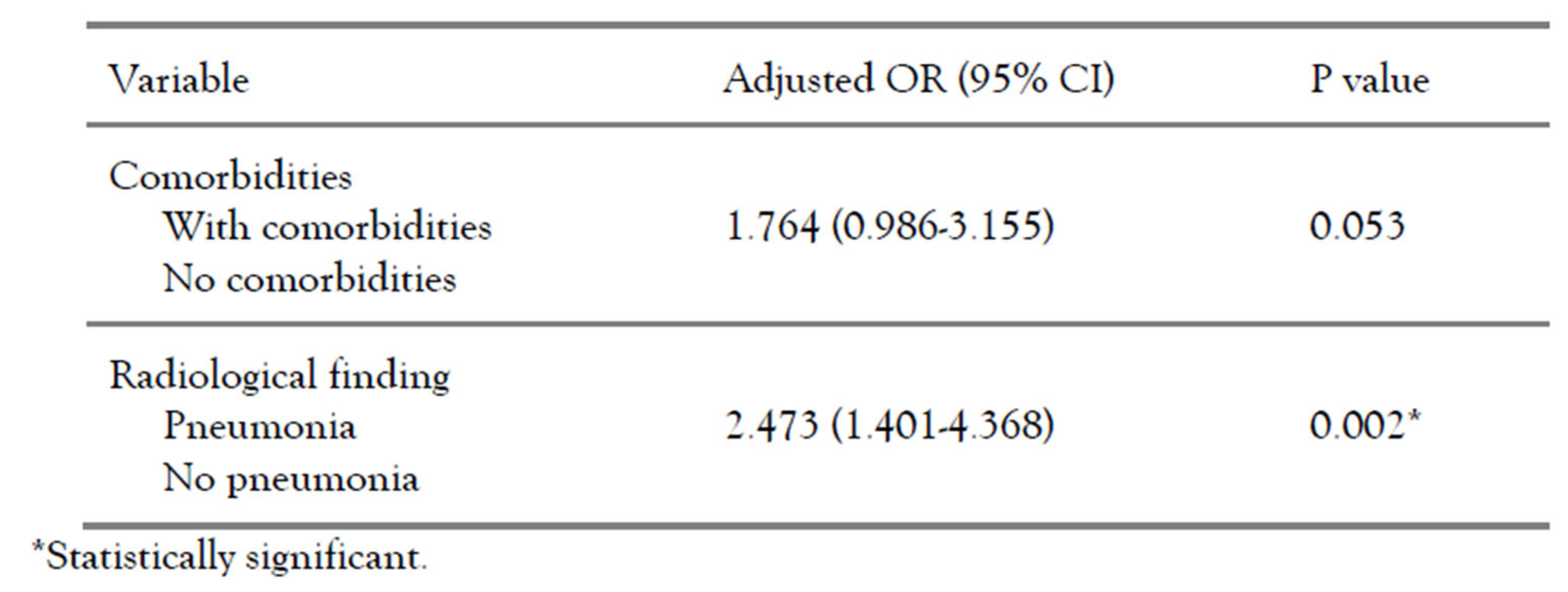

The risk of persistent COVID-19 symptoms was significantly higher in subjects with age >40 years (uOR 1.703, 95% CI 1.089-2.665, p=0.026), with comorbidities (uOR 2.444, 95% CI 1.422-3.542, p=0.001), higher clinical severity (uOR 2.928, 95% CI 1.845-4.648, p<0.001), pneumonia (uOR 2.536, 95% CI 1.442-4.459, p=0.002), and requirement of oxygen therapy (uOR 3.277, 95% CI 1.767-6.077, p <0.001). The results of multivariate analysis are shown in Table 5, revealing that the most influential factor on the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome was pneumonia (aOR 2.473, 95% CI 1.401-4.368, p=0.002). Another likely risk factor was the presence of comorbidities but not statistically significant (aOR 1.764, 95% CI 0.986-3.155, p=0.053).

Table 4.

Bivariate analysis.

Table 4.

Bivariate analysis.

|

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis.

|

Discussion

This study is the first study to investigate the persistent COVID-19 syndrome phenomenon in Indonesia. Most of the respondents did not experience mobility and self-care problems. However, several subjects reported some problems in the dimensions of normal activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Similar results in another study conducted by Ping et al. on 1139 subjects revealed obtained a mean EQ-5D index score of 0.949 with a mean VAS score of 85.52. The most reported problems were pain/discomfort (19%) followed by anxiety/depression (17.6%), with self-care being the least reported problem (1.1%) [20]. A slightly different result was obtained in another study by Garrigues et al. In 120 subjects, the mean EQ-5D index score was 0.86 with a mean VAS score of 70.3 [15]. This difference in results is likely due to the subjective nature of the questionnaire assessment.

This study found that more than half of subjects experienced persistent COVID symptoms lasting up to 3 months. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Lopez-Leon et al. also reported 80% of the COVID-19 patients to have at least one long-term symptom [21]. On the other hand, not so in line with the result, a prospective cohort study by Sudre et al. only reported 13.3% of the patients using an app for reporting symptoms still reported symptoms after 28 days [22]. Meanwhile, Cirulli et al. showed that a total of 36.1% of patients reported at least 1 symptom persisting for longer than 30 days after COVID-19 onset [23]. Apart from demographic characteristics and the number of patients, these variations in prevalence could also be due to the patient selection methods and the time of measurement since symptoms first appeared. The most common symptoms reported by COVID-19 patients during the first 14 days from the acute onset were fever, followed by fatigue, cough, headache, and muscle pain. This is in line with a systematic review and meta-analysis by Rodriguez-Morales et al., which reported fever, cough, and dyspnea as the most common symptoms of COVID-19 [24]. Nevertheless, the most prevalent persistent post-COVID-19 symptoms were fatigue, cough, muscle pain, dyspnea, and headache. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Lopez-Leon et al. reported similar results with the most common persistent symptoms following acute infection being fatigue, headache, attention disorder, hair loss, and dyspnea [21]. A large online-based international cohort study by Davis et al. also reported similar most frequent persistent symptoms [25].

The risk of persistent COVID-19 syndrome is significantly higher in subjects with comorbidities and higher clinical severity through statistical analysis. In agreement with this result, Davis et al. reported that 83% of patients who experienced persistent COVID-19 syndrome had at least one pre-existing condition, and the most reported conditions were allergies (24.1-36.3%), migraines (18.7%), and asthma (17.1%) [25]. Meanwhile, Sudre et al [22]. reported that asthma was the only/unique pre-existing condition that showed a significant association with persistent COVID-19 syndrome, which is still supportive because in this study asthma was the most prevalent comorbid condition found in subjects with persistent COVID-19 syndrome. Individuals with comorbidities are also known to be at a higher risk of developing severe symptoms if infected with SARS-CoV-2 and severe cases are likely to face a bigger risk to experience persistent COVID-19 syndrome due to the fact that the higher the clinical severity the more severe tissue damage or immune system dysfunction, which has previously been discussed as the main possible cause of the persistent COVID-19 syndrome phenomenon [22].

Pneumonia on radiological findings is one of the objective signs of disturbance in lung tissue that will also interfere with lung function, as previously described. In addition, older age, nutritional status, clinical severity, type of care, and oxygen therapy were all associated with a higher risk of long-term COVID-19 in the bivariate analysis, but these factors did not maintain significance in the multivariate analysis. This may be due to confounding by other variables. As used in this study, clinical severity is largely determined by the radiological findings and the use of oxygen therapy, and clinical severity will then determine the type of treatment needed by the patient. For example, a patient with radiological findings of pneumonia and requiring oxygen therapy with a nasal cannula would be categorized as a severe clinical grade, and would necessarily require hospitalization, rather than self-isolation at home. The lack of a representative sample size across all categories may also play a role, as the insignificance of age is a risk factor in the multivariate analysis. In another study, it was found that older age was associated with the risk of persistent COVID-19 syndrome, [22] as it was in this bivariate analysis, but only a small number of subjects with age >60 years old were included in this study.

This study has limitations in data source handling where COVID-19 recovery criteria offered some space of false-negative risk where inadequate nasal swab sample processing or the presence of acute infection even after 14 days of isolation period may make the analysis results differ. The 37 to 63 proportions of healthcare and non-healthcare respondents may lead to differences in the manner of symptoms acknowledgment and the validity of questionnaire responses. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has published the ‘Long COVID-19’ term definition with several domains as diagnostic guidance, but at the time this study was held, the criteria had not been released yet. In the new WHO guidance, it was stated that less than 12 weeks were still falling within the natural course of the acute disease so that the persistent symptoms called long COVID-19 started to be taken into account from 12 weeks of period and above.

Conclusions

The prevalence of the persistent COVID-19 syndrome in Indonesia was quite high, with fatigue being the most reported symptom. Persistent COVID-19 syndrome was shown to impair the quality of life. Factors that most likely influence the incidence of the persistent COVID-19 syndrome were pneumonia in radiological findings and comorbidities. These things can become a concern in efforts to control the COVID-19 disease and its impact on the health and quality of life of COVID-19 survivors. Further research can be explored to investigate more detailed factors such as clinical findings by physician or laboratory biomarkers as predictive and prognostic factors for the incidence of persistent COVID-19 syndrome, with a larger number of samples and a longer study time.

Author Contributions

ADS contributed in conceptualization; methodology; data collection; formal analysis; validation; and writing, review, editing, and approval of the final manuscript. FI contributed in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, and approval of the final manuscript. IPP contributed in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, investigation, and approval of the final manuscript. BA contributed in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, investigation, and approval of the final manuscript. ES contributed in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, investigation, and approval of the final manuscript. MT contributed in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, investigation, and approval of the final manuscript. FH contributed in methodology, writing, review, and approval of the final manuscript. FN contributed in validation; manuscript review; and formatting, editing, and approval of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- Hassan, S.A.; Sheikh, F.N.; Jamal, S.; Ezeh, J.K.; Akhtar, A. Coronavirus (COVID-19): A review of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020, 12, e7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Aghdam, M.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Motallebizadeh, B.; et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection: What is the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) doing to body? A comprehensive systematic review. Rev Med Microbiol. 2021, 32, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.M.; Lee, E.Y.; Singh, R.; et al. Follow-up chest radiographic findings in patients with MERS-CoV after recovery. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2017, 27, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: A 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res. 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.J. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: Putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis (Lond). 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Shang, Y.M.; Song, W.B.; et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020, 25, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Geng, D.; et al. Cerebral micro-structural changes in COVID-19 patients - An MRI-based 3-month follow-up study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020, 25, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntmann, V.O.; Carerj, M.L.; Wieters, I.; Fahim, M.; Arendt, C.; Hoffmann, J.; et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleat, D.; Wain, R.; Miller, B. Long COVID: Reviewing the science and assessing the risk; Tony Blair Institute for Global Change: London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Billig Rose, E.; Lindsell, C.J.; et al. Characteristics of adult outpatients and inpatients with COVID-19 - 11 Academic Medical Centers, United States, March-May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F.; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Harrison, P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: Retrospective cohort studies of 62.354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banda, J.M.; Singh, G.V.; Alser, O.H.; Prieto-Alhambra, D. Long-term patient-reported symptoms of COVID-19: An analysis of social media data. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigues, E.; Janvier, P.; Kherabi, Y.; et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020, 81, e4–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, S.J.; McIvor, C.; Whyatt, G.; et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID - 19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Barnett, J.; Brill, S.E.; et al. "Long-COVID": A cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalization for COVID-19. Thorax. 2021, 76, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, K.; Lehto, J.T.; Sutinen, E.; Kautiainen, H.; Myllärniemi, M.; Saarto, T. mMRC dyspnoea scale indicates impaired quality of life and increased pain in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2017, 3, 00084–02017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, W.; Zheng, J.; Niu, X.; et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0234850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-León, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3769978 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3769978.

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; et al. Attributes and predictors of long-COVID: Analysis of COVID cases and their symptoms collected by the Covid Symptoms Study App. medRxiv. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, E.T.; Barrett, K.M.S.; Riffle, S.; et al. Long-term COVID-19 symptoms in a large unselected population. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Ocampo, E.; et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020, 34, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2022.