Introduction

The pandemic coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is mainly associated with different levels of respiratory impairment, ranging from mild pneumonia to acute respiratory distress syndrome, even multiple organ failure and death [

1]. Beyond the pulmonary involvement, severe cases of COVID-19 showed concomitant extrapulmonary organ involvement, such as kidney and cardiac injury or endocrine and metabolic disturbances [

1].

The pathogenic process of COVID-19 occurrence involves angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors and transmembrane protease serine type-2 (TMPRSS2), that allow virus binding (through the receptor-binding domain within the S1 domain) and mediates entry into the cell [

2]. Considering that the distribution of these ACE2 receptors and TMPRSS2 is not strictly concentrated in the pulmonary tissue, other organs expressing them may be affected [

2]. In addition to the direct cytotoxic effects of the virus, cytokine overproduction, endothelial cell damage and thrombo-inflammation may further explain extrapulmonary organ involvement [

1]. Ever since the first studies dedicated to the pathological mechanisms implicated in COVID-19, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) was considered a key factor for explaining multisystemic organ involvement [

1]. Taking into account the main physiological effects of angiotensin II, such as systemic vasoconstriction, aldosterone synthesis, electrolyte homeostasis, bradykinin regulation, inflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways induction, SARS-CoV-2-related effects on RAAS may explain to some extent the pathophysiological consequences of COVID-19 [

1].

From the first available COVID-19 reports, a constant cardiac involvement was signaled [

3]. ACE receptor distribution in the heart tissue was already noted, with an increased density at the level of a type of perivascular mural cells, called pericytes, explaining the frequent involvement of the myocardial tissue in COVID-19 [

2]. However, SARS-CoV-2 infection-associated cardiovascular dysfunction may also be related to the severe hypoxemia or to the exacerbated systemic inflammatory response [

2]. A variety of cardiac manifestations were quantified since the pandemic outbreak, including myocardial infarction, myocarditis, arrhythmias and acute heart failure [

1].

As in case of other diseases with infectious etiology, like influenza, Epstein-Barr virus infection or Lyme disease, post-acute sequelae following COVID-19 have also been reported [

4]. Although long COVID was mainly associated with mild symptoms such as fatigue, hair loss or persistent cough, there are several reports on late onset of severe tachyarrhythmias, myocardial remodeling, vasculitis or polyradiculoneuropathies [

4].

Notwithstanding cases of pericarditis secondary to COVID-19 were also reported, but its real prevalence is still unknown [

3]. Li et al. mentioned that pericardial effusion is not an uncommon feature of critically ill COVID-19 patients, however it was not found to have an independent impact on patients’ prognosis [

5]. The pathophysiological mechanism of pericarditis in COVID-19 patients is not fully understood, but a similar mechanism as in other cardiotropic viral infections is suspected [

3].

If most available data regarding pericardial involvement are referring to the acute phase of the disease, very few reports are dedicated to the post-acute phase [

3]. Here we describe the case of young male patient who developed cardiac tamponade one month after clinical recovery from SARS-COV-2 infection.

Case report

We present the case of a 42-year-old male patient who was admitted into the intensive care unit (ICU) for respiratory and renal dysfunction associated with hemodynamic instability. The patient’s recent medical history reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 mild infection one month previously that did not require hospitalization and apparently resolved with symptomatic treatment. However, four days prior to admission, the patient developed high-grade fever (up to 40 °C) and oliguria. On admission, the real-time (RT)-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 was negative. Initial imaging examination with thoracic computed tomography (CT) revealed a 3.5-centimetre-wide pericardial effusion situated laterally from the right atrium, while the abdominal ultrasound had no remarkable features apart from mild left perirenal effusion.

Upon admission in the ICU, the patient was in a severe state, with pale, diaphoretic skin and mucosa, blood pressure of 144/88 mmHg, pulse 139 beats per minute and with evident respiratory distress, thus high flow nasal oxygen therapy (HFNO) was initiated—flow 45 L/min and FiO2 0.45. No vasopressor or inotropic support was needed at the time.

Laboratory investigations showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia, high creatinine and liver enzymes levels, metabolic acidosis with hyperlactatemia. Surprisingly, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) showed markedly increased values (6148.8 pg/mL with laboratory range under 125 pg/mL). Toxicological urinary screening tests came back negative. Cardiac transthoracic ultrasound indicated a 15-20% left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) and persistent pericardial fluid with no signs of cardiac tamponade at the time of examination. Cardiovascular surgery specialists confirmed there was no indication for a further emergency surgical step.

Considering acute renal dysfunction, prompt continuous renal replacement therapy with hemodiafiltration was started. Further management focused on treating main organ dysfunctions and supporting vitals with hydroelectrolyte and acid-base rebalancing, wide spectrum antibiotics (meropenem 2 g every 8 h by intravenous continuous infusion and linezolid 600 mg intravenous every 12 h), and adjunctive therapies like antipyretics, proton-pump-inhibitors (omeprazole 40 mg intravenous once daily), heparin therapy, insulin, and parenteral multivitamins (Soluvit N).

Twelve hours after ICU admission, the patient rapidly deteriorated with altered general state, with aggravating respiratory dysfunction and an oxygen saturation of 85% despite of an increased fraction of inspiratory oxygen (FiO2), imposing invasive mechanical ventilation initiation. Taking into account the escalating cardio-circulatory dysfunction, vasopressor support with noradrenaline was started (maximal dose 1.3 µg/kg/min). Immediately after endotracheal intubation, tracheal secretion was sent for microbiology PCR tests for agents responsible for severe acute respiratory infection (SARI), such as SARS-CoV-2,influenza A and B, adenovirus, Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, coxsackie virus, Chlamydia pneumoniae or parainfluenza viruses. Surprisingly, only RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 came back positive, although the initial test had been negative. Serological markers for hepatitis B and HIV were negative. Systemic bacterial infections were excluded based upon three sets of blood cultures that came back negative.

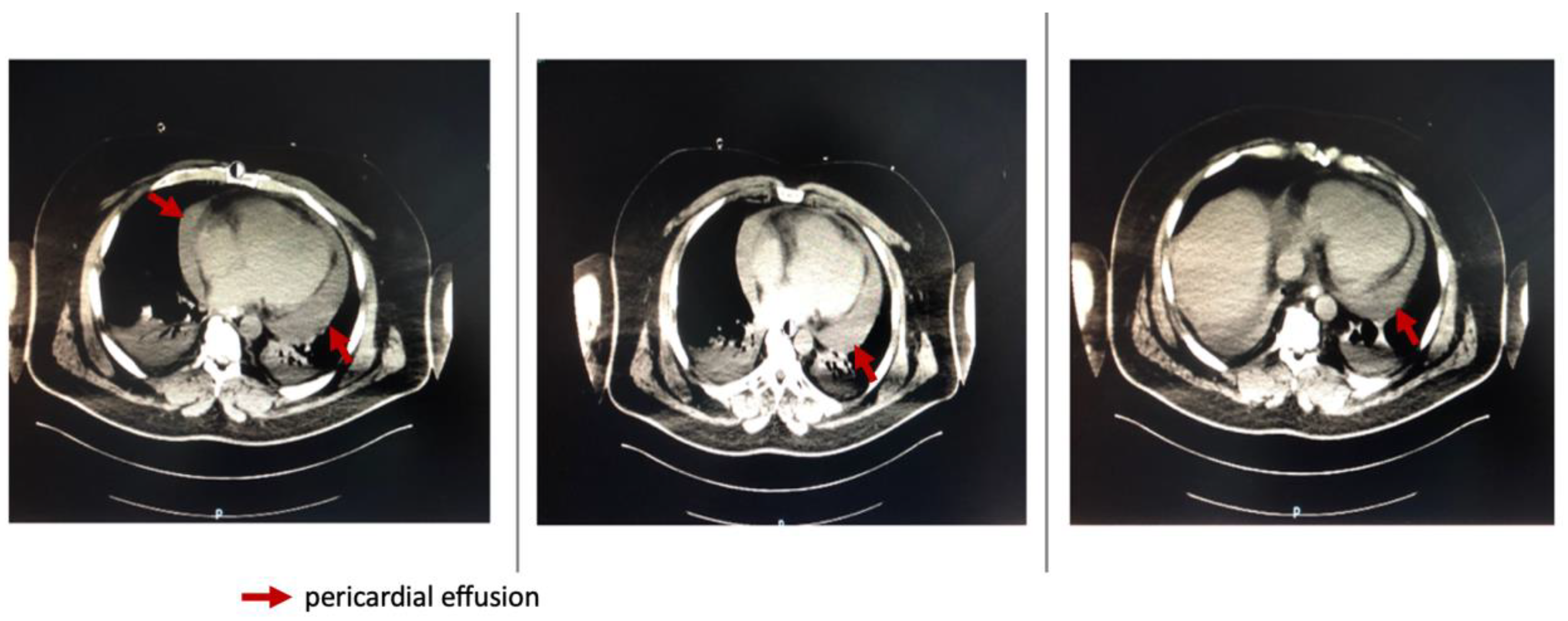

Repeated thoracic CT displayed significant circumferential pericardial effusion adjacent to the left ventricle and minimal bilateral pleural effusion (

Figure 1).

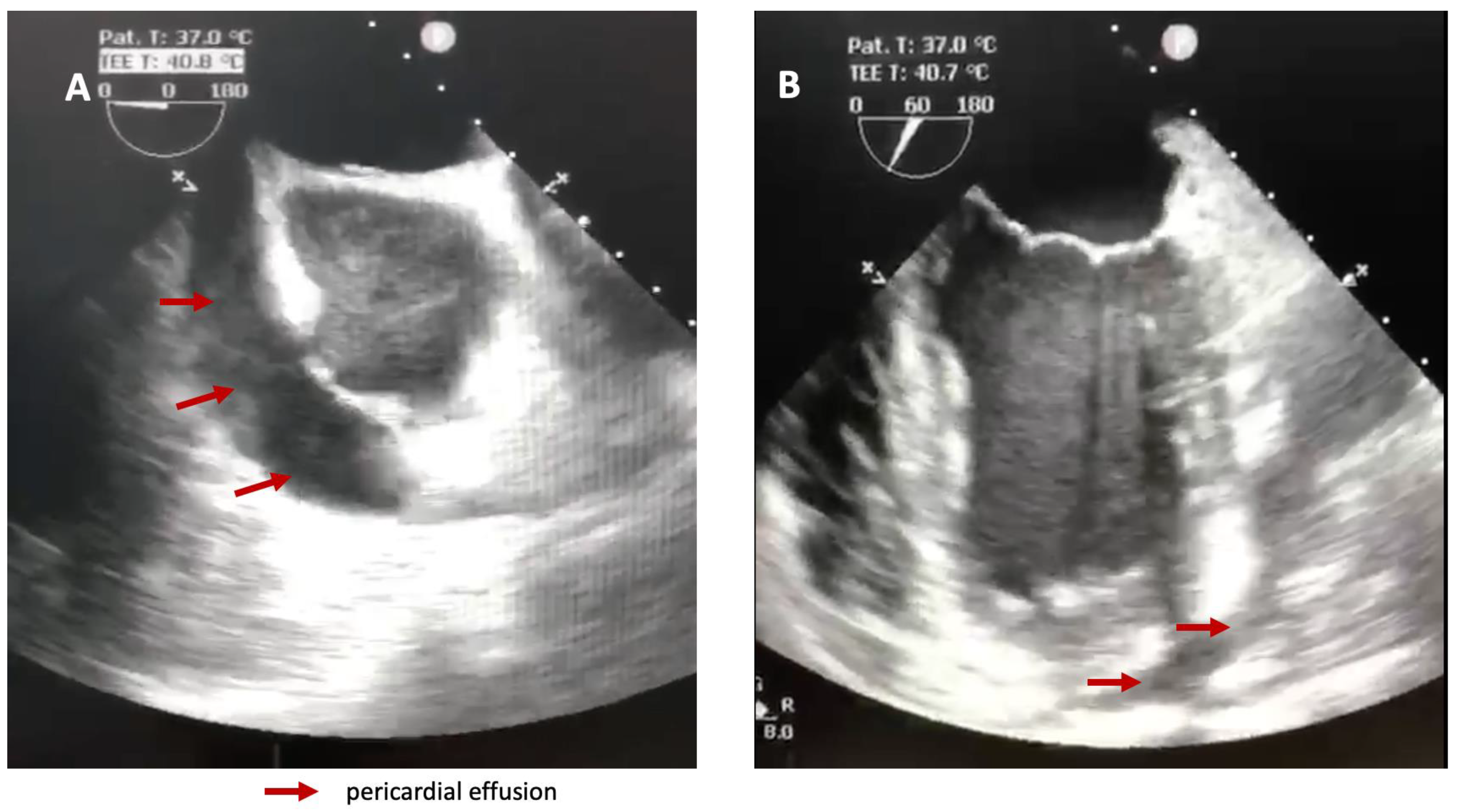

A transesophageal heart ultrasound was promptly performed and confirmed the impressive amount of liquid in the pericardium and right ventricular collapse (

Figure 2).

Taking into consideration the rapid and massive increase of the pericardial fluid leading to cardiac tamponade with deteriorating cardiocirculatory status and clear signs of obstructive shock, the cardiovascular surgeon decided to do an emergency pericardiocentesis.

Analysis of the pericardial fluid confirmed an exudative origin (albumin 2.81 g/dL, total protein 4.55 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 577 U/L), while histopathological examination showed congestion of vessels in the fibro-adipose tissue and areas of chronic inflammation with rare lymphocytes and mesothelial cells. RT-PCR testing for Mycoplasma tuberculosis in the pericardial tissue came back negative. Unfortunately, no pericardial fluid RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 was ordered.

The immediate postoperative status was not favorable, with hemodynamic instability imposing continuous vasopressor support and continuous hemodialysis.

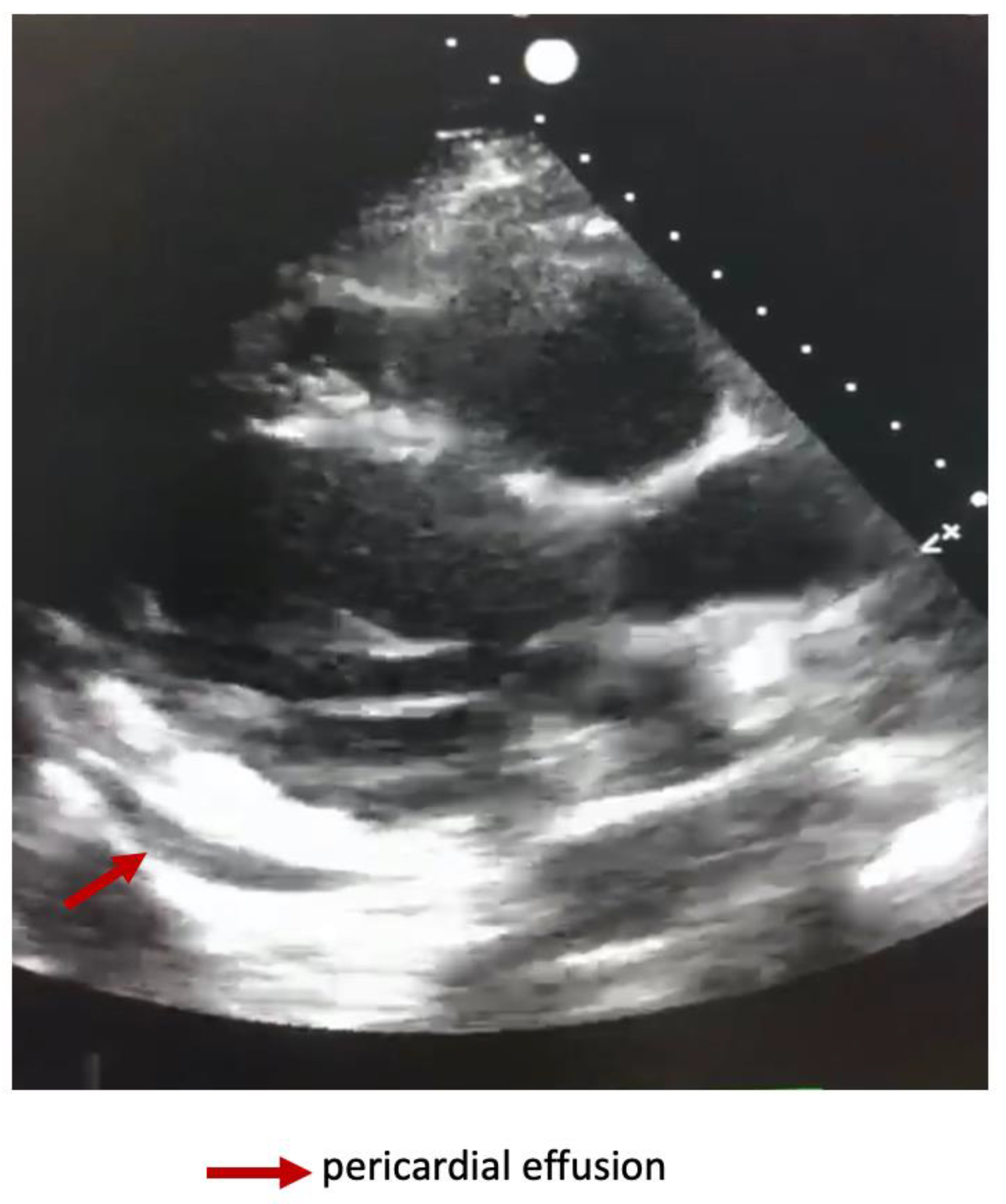

Dynamically performed cardiac ultrasound noted an improvement in the LVEF at 45-50% and minimal pericardial effusion (

Figure 3).

The patient’s state slowly improved with ceasing of vasopressor support and reinstalment of diuresis. Paraclinical tests shared a similar trend with improvement of metabolic acidosis parameters, normalization of inflammatory markers and no leukocytosis. Considering negative microbiology results for bacterial infections, antibiotic administration was ceased on day 5 of hospitalization.

Given his favorable evolution, the patient was discharged into the cardiology unit on day five to pursue heart parameter monitoring and initiate anti-hypertensive treatment. No recurrence of pericarditis occurred during patient’s hospital stay, thus he was discharged and referred to a rehabilitation facility on day 12.

Discussion

The reported cardiovascular manifestations secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection are very heterogenous including mild symptoms such as chest pain or myocardial injury, acute heart failure and arrhythmias [

3]. COVID-19-related pericardial involvement is rare, as a result very few cases of cardiac tamponade are reported in the literature.

We presented the case of 42-year-old male patient who was admitted to the ICU presenting acute hypoxemic respiratory and renal dysfunction. As above-mentioned his clinical course rapidly evolved to typical obstructive shock caused by cardiac tamponade, which imposed emergency pericardiocentesis. The case’s highlight is that one month prior to ICU hospitalization, he tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, however the course of the initial disease was rather mild. Considering that the most frequent causes for cardiac tamponade were excluded, a late COVID etiology was incriminated. Interestingly in the reported case the first nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR test was negative, advancing a different etiology for the pericardial effusion and thus no SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR from the pericardial fluid or tissue was ordered.

The pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 pericarditis are still unknown, however an exacerbated inflammatory mechanism was incriminated, similar to other viral infections [

6]. The result from the biopsy report sustains the suspected inflammatory etiology of the pericardial effusion. A similar biopsy result was also indicated by Amoozoar et al. who indicated the presence of acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrates in the pericardial tissue [

6].

The very few reported cases of cardiac tamponade secondary to COVID-19 were identified within the acute phase of the disease and none was already in the recovery phase [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Pericardial effusion was frequently reported to be associated with severe COVID-19 disease, however in the presented case the course of the disease was mild without the need for hospital admission [

5].

Although it was reported that myocardial inflammation was a frequent condition found in patients during the recovery phase of COVID-19, further data regarding the cardiovascular sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection is scarce [

8].

The available data concerning late effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection were initially based on social support group reports, the very abundant evidence of a new entity called “long COVID” was rapidly recognized by the scientific community [

4]. The most typically reported complications associated with late COVID are mild symptoms such as chest pain, abdominal symptoms, fatigue, sleep disturbances and cognitive dysfunction [

4]. However, rare cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome due to COVID-19 were described among adults and pediatric population [

4]. No data regarding late-onset cardiac tamponade after COVID-19 is currently available.