Native Valve Emphysematous Enterococcal Endocarditis: Expanding the Differential Diagnosis

Abstract

Introduction

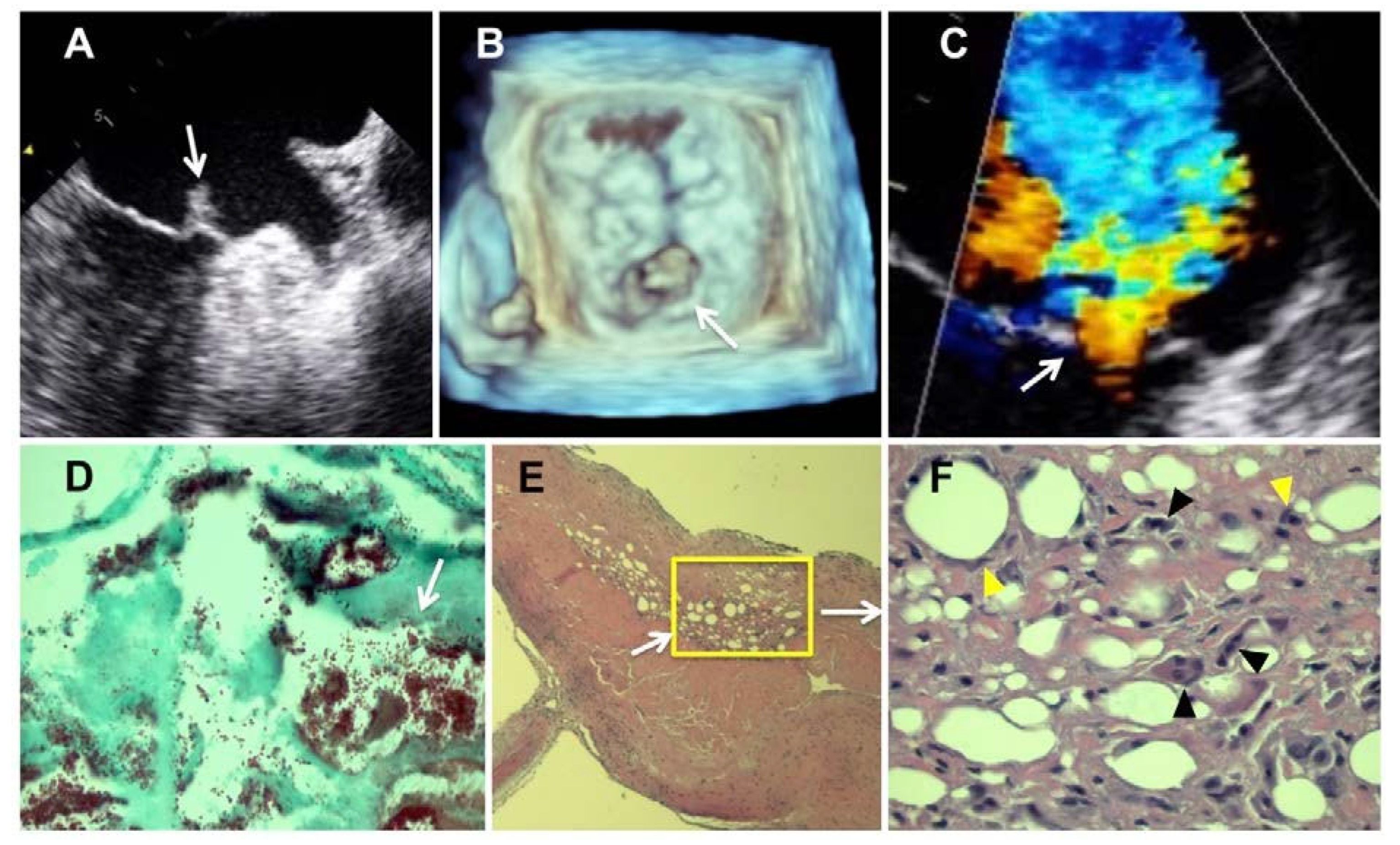

Case report

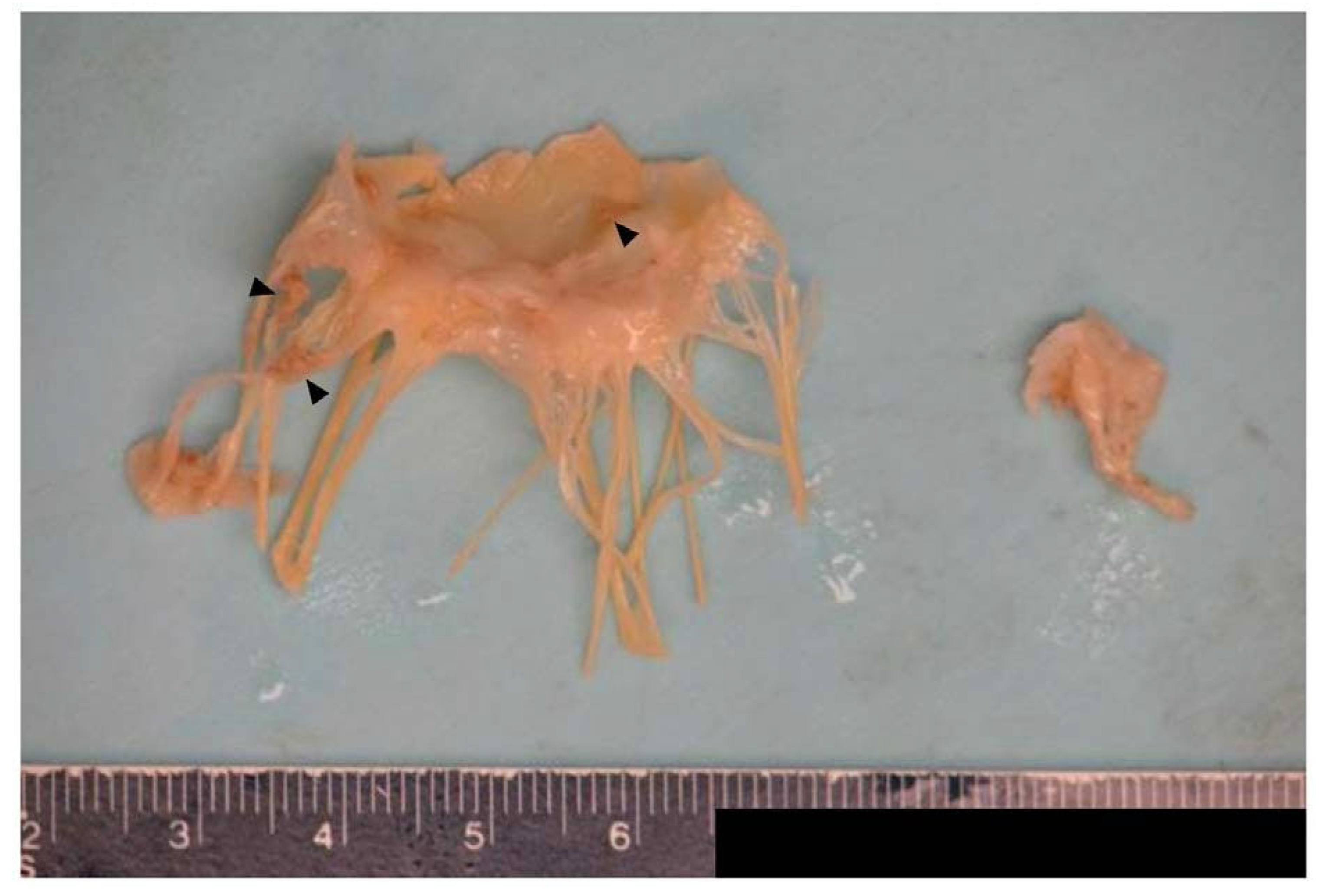

Pathology results

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

Consent

References

- Beganovic, M.; Luther, M.K.; Rice, L.B.; Arias, C.A.; Rybak, M.J.; Laplante, K.L. A review of combination antimicrobial therapy for Enterococcus faecalis bloodstream infections and infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018, 67, 303-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.J.; Yi, J.E.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.J. . Emphysematous endocarditis caused by AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018, 97, e9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesler, S.; Kim, H.; Perlman, D.; Dincer, H.E.; Thenappan, T.; Tomic, R. Air in the left ventricle. An unusual case of endocarditis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016, 193, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.; Stephens, E.H.; Garshick, M.; et al. Native valve emphysematous endocarditis caused by Finegoldia magna in a novel pathogenic role. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2016, 24, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.; Thomas, M. Escherichia coli emphysematous endocarditis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020, 20, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.C.; Berard, C.W. . Gas gangrene of the heart in clostridial septicemia. Am Heart J. 1967, 74, 482-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vliet, H.J.; Niessen, H.W.; Perenboom, R.M. . Myocardial air collections as a result of infection with a gas producing strain of Escherichia coli. J Clin Pathol. 2004, 57, 660-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dhahli, A.S.; Al-Umairi, R.; Elkadi, O. A rare case of emphysematous endocarditis caused by Escherichia coli. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randjelovic, P.; Veljkovic, S.; Stojiljkovic, N.; Sokolovic, D.; Ilic, I. Gentamicin nephrotoxicity in animals: current knowledge and future perspectives. EXCLI J. 2017, 24, 388-99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organism | Diagnostic tools | Presentation | Treatment | Outcome | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Non-contrast enhanced chest CT Transthoracic echocardiogram | Air bubbles surrounding mitral annulus Hyperechogenic mass on posteromedial side of mitral annulus 2 eccentric mitral jets | Meropenem Surgery was advised but was declined by the patient | The patient died 5 weeks after initial presentation | Kim et al. (2018)2 |

| E. coli | Contrast enhanced CT angiogram Head CT Transesophageal echocardiogram | Gas-containing vegetation in left atrium and posterior mitral annulus Gas-containing embolus completely occluding left femoral artery Right occipital abscess | Mitral valve replacement and left femoral embolectomy Amoxicillin therapy following mitral valve replacement | After completing the amoxicillin treatment, the patient followed up with recurrent fevers. Head CT revealed a right occipital lobe abscess which was treated with ceftriaxone for 28 days. The patient had a good recovery. | Law D, Thomas M (2020)5 |

| E. coli | Thoracic CT Cardiac ultrasound | Dehydration and high fever Multiple splenic abscesses Signs of left sided heart failure Left ventricular inferoposterior wall motion abnormalities | Antibiotic treatment | The patient died due to ventricular fibrillation | van der Vliet HJ, Niessen HW, Perenboom RM (2004)7 |

| E. coli | Chest X-ray Non-contrast enhanced head CT Pulmonary angiography CT | Hypodense foci in both centrum semiovali Air containing lesion around mitral valve Mobile hyperechoic mass in anterior mitral valve leaflet Mild mitral regurgitation | Ceftriaxone was used empirically Piperacillin was used after E. coli confirmation | The patient died 4 days after initial presentation due to ventricular arrythmia | Al Dhali AS, Al-Umairi R, Elkadi O (2021)8 |

| C. koseri | Chest and abdomen CT Transesophageal echocardiogram | Air in left ventricle and within renal collecting system Increased echogenic density of anterior papillary muscle Echo-dense vegetation in the anterior and posterior mitral leaflets Severe mitral regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension | Mitral valve replacement | Complete recovery of kidney function The patient continues to have mild cognitive deficits, left-sided weakness, and dysphagia | Kesler S et al. (2016)3 |

| F. magna | Non-contrast head and chest CT Transthoracic echocardiogram | Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response Air found in the posterior mitral annulus, left ventricular wall, aorta, and right anterior frontal lobe of the brain Upon autopsy, gas bubbles and clusters of bacteria were found in areas of myocardial necrosis | Vancomycin, levofloxacin, aztreonam, metronidazole were used empirically Vancomycin, meropenem, rifampin, and gentamicin were used for presumed embolic endocarditis | The patient died from cardiac arrest 3 days after initial presentation | Cohen M et al. (2016)4 |

| Clostridium | Autopsy | Roberts W, Berard C. (1967)6 |

© GERMS 2025. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tessier, S.; Durgham, A.; Krinock, M.; Singh, A.; Longo, S.; Nanda, S. Native Valve Emphysematous Enterococcal Endocarditis: Expanding the Differential Diagnosis. Germs 2021, 11, 608-613. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1297

Tessier S, Durgham A, Krinock M, Singh A, Longo S, Nanda S. Native Valve Emphysematous Enterococcal Endocarditis: Expanding the Differential Diagnosis. Germs. 2021; 11(4):608-613. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1297

Chicago/Turabian StyleTessier, Steven, Anthony Durgham, Matthew Krinock, Amitoj Singh, Santo Longo, and Sudip Nanda. 2021. "Native Valve Emphysematous Enterococcal Endocarditis: Expanding the Differential Diagnosis" Germs 11, no. 4: 608-613. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1297

APA StyleTessier, S., Durgham, A., Krinock, M., Singh, A., Longo, S., & Nanda, S. (2021). Native Valve Emphysematous Enterococcal Endocarditis: Expanding the Differential Diagnosis. Germs, 11(4), 608-613. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1297