Abstract

Introduction: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is associated with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Vaccination is one aspect of public health policy aimed at eliminating HBV infection. After the implementation of an HBV vaccination program for newborns in Thailand, the estimated residual infection rate was 3.5%. However, that study was conducted in only 5,964 participants in seven provinces and only 22 years after the start of the campaign. This study aimed to evaluate the HBV seroprevalence rate in Thailand in larger sample size and a longer duration after program implementation using HBV surveillance. Methods: This was a surveillance study conducted in 20 provinces in northeast Thailand. The study period was between July 2010 and November 2019. Rates of HBV seroprevalence in each province and overall were calculated. Participants were divided into two groups: those vaccinated under the national campaign and those who were not. Participants aged 0-20 years were used as references, while other age groups (intervals of 10 years) were comparators. Residual HBV seroprevalence after the vaccination program was calculated with odds ratio for HBV seroprevalence in each age group. Results: There were 31,855 subjects who participated in the project. Of those, 1,805 (5.7%) had HBV. The HBV seroprevalence rate in the national HBV vaccination group was significantly lower than that in those not vaccinated under the national program (1.0% vs 5.9%; p<0.001). Seroprevalence was 1.0% in participants ≤20 years of age. Participants 31-40 years of age had the highest odds ratio (10.41), followed those 21-30 years of age (7.42). Conclusions: This real-world surveillance study showed that residual HBV infection was 1.0% after nearly 30 years of nationwide HBV vaccination.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is common in developing countries. The WHO reported in 2015 that 257 million people (3.5% of global population) were infected with HBV worldwide [1]. HBV infection is associated with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Previous studies have found that chronic HBV infection is an age- related condition [2,3]. Approximately 90% of chronic HBV cases are found during the first six months of life, followed by 20-60% from six months to five years, and less than 5% in adults [2,3].

Vaccination is one strategy used to prevent infection. The prevalence of HBV infection has decreased from 4.7% to 1.3% due to vaccination [1]. A 2016 report found that the global HBV vaccination rate for children under one year of age was 87%. However, HBV prevalence and vaccination coverage rates vary by country. In Malawi for example, the vaccination coverage is 84% and HBV prevalence is 8.20%, while those in Denmark are less than 1% and 0.24%, respectively [4]. Since 1988, The provinces of Chiang Mai and Chon Buri have had a universal HBV vaccination program for newborns. Subsequently in 1992, this became the national policy, as Thailand was an endemic for HBV infection. The HBV vaccine is given to infants in combination with the DTPw vaccine over four doses (at birth and 2, 4, and 6 months of age) to reduce cost and increase compliance. One study estimated the residual infection rate in Thailand to be approximately 3.5% [5]. However, that study was conducted in only 5,964 participants in seven provinces and only 22 years after the implementation of the national vaccination campaign. This study thus aimed to evaluate the HBV seroprevalence rate using HBV surveillance in a larger sample size and over a longer duration.

Methods

This was a surveillance study conducted in 20 provinces in northeast Thailand. The study period was between July 2010 and November 2019. Surveillance was conducted in multiple areas in each province on a random basis. The survey was open to the public and consisted of HBV screening and educational activities regarding HBV awareness led by a multidisciplinary health care team. All participants aged <60 years were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research (Thailand; HE621134). As surveillance data were retrospectively reviewed, informed consent was not required.

During surveillance, demographic data were collected and each participant underwent an HBV screening test using a rapid point-of-care assay (One Step Rapid Test for HBV; Healgen, USA), which yields a sensitivity and specificity of 99.4% and 99.5%, respectively. Those who tested positive for HBV were referred for proper treatment. HBV seroprevalence (overall and in each province) was calculated by using descriptive statistics. Participants were divided into two groups based on whether or not they had been vaccinated under the national campaign. Those aged 0-20 years were used as a reference, while other age groups (intervals of 10 years) were used as comparators. Residual HBV seroprevalence after the vaccination program was calculated with odds ratio for HBV seroprevalence in each age group. Pearson’s Chi squared test was used to evaluate differences in HBV seroprevalence among age groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval in each age group. Note that these analyses were based on the assumption that those over 20 years of age had not been vaccinated under the national program. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 10.1 (College Station, USA).

Results

Of the 31,855 subjects who participated the project, 1,805 (5.7%) were positive for HBV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection according to an HBV surveillance project in northeast Thailand.

Seroprevalence rates ranged from 2.3 to 10.7% with an average vaccination rate of 12.2% (overall), 11.9% (age of 20 years or under), and 12.2% (over 20 years of age). The seroprevalence rate was highest in 2011 (11.8%). Beung kan and Khon Kaen provinces had the highest rates at 10.7%, and 8.7%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection by province according to an HBV surveillance project in northeast Thailand.

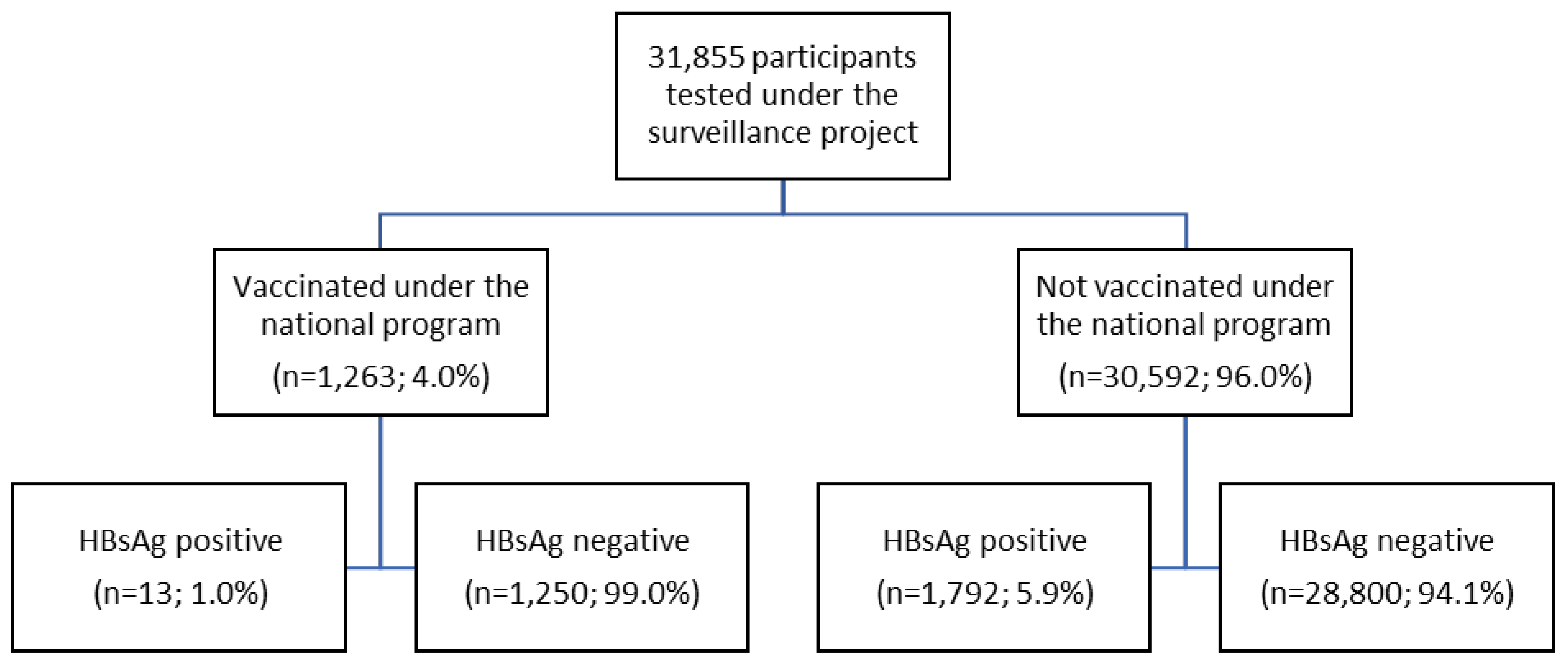

A total of 1,263 participants (4.0%) were vaccinated under the national program, as shown in Figure 1. The HBV seroprevalence rate in the vaccination group was significantly lower than in the non-vaccination group (1.0% vs 5.9%; p<0.001 by Fisher’s Exact test). No participants 0-10 years of age tested positive, while the age group of 11-20 years had a seroprevalence rate of 1.2% (Table 3). HBV seroprevalence differed significantly by age group (Chi square of 294.91; p<0.001). In total, the HBV seroprevalence rate of subjects 20 years or under was 1.0% (13 of 1,263), compared to 5.9% in those over 20 years. In addition, the rate in each age group over 20 years differed significantly from that of participants aged 0-20 years (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 3.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection by age group according to an HBV surveillance project in northeast Thailand.

Participants aged 21-30 years had a seroprevalence rate of 7.2%. Participants 31-40 years of age had the highest odds ratio of 10.41 followed by those 21-30 years of age (odds ratio of 7.42), as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

This study found that the HBV seroprevalence in northeast Thailand (5.7%) was higher than those reported by the WHO (2% for Southeast Asian countries and 1.6% in India [1,6]. The seroprevalence rate found in this study was also higher than the global prevalence of 4.9% and previously reported national prevalence of 4.0% [4], which may be due to the data having been gathered only in northeast Thailand. However, the HBV seroprevalence rates in specific provinces were also higher than in previously reports (Table 2). For example, that of Khon Kaen province was 8.7%, while previous studies have found rates of 2.1% in blood donors and 4.6% in the elderly [7,8]. Note that the rate in this study was also higher than two specific populations in previous studies. As previously mentioned, the HBV seroprevalence rate in this study was referred to only specific population in the surveillance. Seroprevalence also varied among provinces. These differences may have various causes such as varying socioeconomic circumstances, or migration to urban areas [9]. Additionally, people in some provinces may be more likely to use alternative medicine, acupuncture, or tattooing (locally believed to provide protection) as preventative measures against HBV. However, the reasons for these provincial differences should be investigated further.

Participants aged 21-30 years still had a significant odds ratio for HBV infection (odds ratio of 7.42; 95% CI 4.24, 12.99) than those under 20 years, despite the national vaccination program having been implemented nearly 30 years prior (Table 3). This implies that the vaccination program may have taken approximately 20 years to become effective. A study from China found that chronic HBV infection decreased from 10.5% to 0.8% in children age of less than 15 years [9]. This suggests it may take up to 15 years for HBV vaccination programs to have a real-world impact.

We also found a 1.0% residual infection rate, similar to the 0.8% rate found by a study in China [9]. This may be explained by the coverage of the vaccination program and type of vaccines used. Both China and Thailand have vaccination coverage of over 99% in children under one year of age [4], which may result in approximately one percent residual infection. Additionally, HBV vaccination may not be 100% effective, and effectivity can vary by vaccine type and method of administration. For example, the Heplisav-B vaccine has a higher seroprotection rate than Engerix-B (89-96% vs 62-81%) [10], A previous study found that 2 doses of Heplisav-B resulted in a higher seroprotective rate than the 3 doses of Engerix-B in patients with chronic liver disease (63% vs 45%; p=0.03) [11]. Although the residual HBV seroprevalence rate in our study was lower than previously reported (1.0% vs 3.5%) [5], additional prevention strategies may be necessary. The differences in our findings may be due to the larger sample size and the national HBV vaccination program having been in place for a longer period.

There are some limitations to this study. First, although this study population was quite large and distributed throughout all provinces in the northeast, the results may not reflect national rates. Second, some participants in the group not vaccinated under the national program may have been vaccinated by other means, resulting in a lower odds ratio (Table 3). Third, the HBV test was a point-of-care test, be it one with good sensitivity and specificity. Finally, HBV serological types were not evaluated.

Conclusions

This real-world surveillance study showed that residual HBV infection was 1.0% nearly 30 years after the implementation of a national HBV vaccination program.

Author Contributions

TS and WS were responsible for the concept and study design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. CR, AW, and KS participated in data acquisition and interpretation and critical revision for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global- hepatitis report2017/en/ (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Sundaram, V.; Kowdley, K. Management of chronic hepatitis B infection. BMJ. 2015, 351, h4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, A.; Horn, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krause, G.; Ott, J.J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015, 386, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018, 3, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posuwan, N.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Sa-Nguanmoo, P.; et al. The success of a universal hepatitis B immunization program as part of Thailand’s EPI after 22 years’ implementation. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0150499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, R.P.; Balakrishnan, S.; Varadhan, H.; Shanmugam, V. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection from a population-based study in Southern India. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018, 30, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimparlee, N.; Oota, S.; Phikulsod, S.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Poovorawan, Y. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus in Thai blood donors. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011, 42, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Posuwan, N.; Vuthitanachot, V.; Chinchai, T.; Wasitthankasem, R.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Poovorawan, Y. Serological evidence of hepatitis A, B, and C virus infection in older adults in Khon Kaen, Thailand and the estimated rates of chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection in Thais, 2017. PeerJ. 2019, 7, e7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, D.Y.; Li, J.M.; Lin, S.; et al. Global burden of acute viral hepatitis and its association with socioeconomic development status, 1990-2019. J Hepatol. 2021, 75, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuan, R.K.; Janssen, R.; Heyward, W.; Bennett, S.; Nordyke, R. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination using HEPLISAV™ in selected adult populations compared to Engerix-B® vaccine. Vaccine. 2013, 31, 4024–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad, W.; Alukal, J.; Zhang, T.; Maheshwari, A.; Thuluvath, P.J. Two-dose hepatitis B vaccine (Heplisav-B) results in better seroconversion than three-dose vaccine (Engerix- B) in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2021, 66, 2101–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2021.