Abstract

Introduction: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has led to a global pandemic among patients of all ages around the world. A new delayed inflammatory syndrome, with potentially severe evolution, has been described in the pediatric population, a population previously considered to be less vulnerable to the severe forms of COVID-19. Case report: We describe the first clinical case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) in a 7- year-old child of the Ternopil region, Ukraine. Our clinical case fulfills the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health definition of MIS-C temporarily associated with COVID-19 –systemic disease with long-term fever, multiorgan dysfunction, laboratory evidence of hyperinflammation, positive SARS-CoV- 2 tests, and the absence of an alternative cause that would explain the clinical picture. The patient was treated according to the treatment guidelines and subsequently was discharged with the resolution of his clinical symptoms. Conclusions: This clinical case draws the attention of general practitioners and pediatricians to the importance of timely diagnosis of a rare, but potentially severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporarily associated with COVID-19 in children.

Introduction

The rapid spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to a global pandemic among patients of all ages around the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) data for February 2021 showed that COVID-19 affected almost 105.4 million people and caused more than 2.3 million deaths in the World [1]. According to the Center for Public Health, as of February 2021 in Ukraine 1.2 million cases were recorded, with 24.1 thousand deaths [2].

As the research on the ongoing pandemic caused by a novel respiratory virus continues to grow, it appears that young children are less susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests most laboratory- confirmed cases of COVID-19 in children result in mild disease, with severe disease in children considered rare [3,4]. However, over the past months, an increase in the number of children presenting to hospitals with a phenotype resembling multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) has led to an alert of health authorities. MIS-C is a dangerous and immune-mediated post-infectious complication of SARS-CoV-2, characterized by extreme inflammation, fever, abdominal symptoms, conjunctivitis, and rash in three to four weeks after COVID-19 infection. Many children progress rapidly into shock and cardiorespiratory failure and require intensive care [4,5,6].

Ternopil is one of the major cities of Western Ukraine with a population of around 250 thousand people. Based on statistical reports, during the 10 months of the pandemic in Ternopil COVID-infection was diagnosed in 2135 children, 180 of them were treated in the infection department of Ternopil Regional Children Hospital, 33 children in PICU (pediatric intensive care unit). The multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) was diagnosed in 4 children [7].

We report the first case of MIS-C diagnosed in the Ternopil region of Ukraine in a child of 7 years, in October 2020.

Case report

A boy, 7 years old, was hospitalized to the PICU on the 5th day from the onset of the disease with complaints of fever up to 39.0°C for 5 days, intense headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, drowsiness, and rash on the trunk, inguinal region, perineum.

The disease had started 5 days earlier with fever, headache, sore throat, rash in the perineum. The next day, liquid fecal stool once a day appeared. On the 4th day of the disease, there was repeated vomiting, abdominal pain, intense headache. On the 5th day, the rash spread to the torso, neck, eyelids, and the skin of the abdominal wall became swollen. High-grade fever up to 39°C has been persisting for five days. The patient was hospitalized. Allergic and hereditary anamnesis of the boy was favorable.

On admission, the child’s general condition was severe due to high fever, intoxication syndrome, diffuse exanthema, catarrhal signs, and edema. The boy was sleepy, anxious, consciousness was clear. The skin was pale, with an icteric tinge, abundant spotted and large- macular rashes of bright red color with a tendency to merge on the trunk, face, behind the ears, and axillary areas, spread to the inner surfaces of the thighs, perineum, scrotum (Figure 1 A-C). There was edema of the eyelids, feet, and the abdominal wall. The lips were dry, red. The mucous membrane of the oropharynx was hyperemic. The tongue was covered with a white coating. The eyelids were hyperemic with signs of bilateral dry conjunctivitis (Figure 1D). Relative borders of the heart corresponded to the age, heart tones were rhythmic, pure, sonorous. There was clear resonance sound over the lungs by percussion and vesicular breathing without rales by auscultation. The abdomen was tense, painful, deep palpation was impossible. There were mild symptoms of peritoneal irritation. The liver was +2 cm below the edge of the costal arch, the spleen was not enlarged. Meningeal signs: pronounced stiffness of the occipital muscles up to 2 cm, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs were negative. On the 4th day, swelling appeared in the feet of both lower extremities.

Figure 1.

(A-D). Maculopetechial rash with a tendency to merge on the trunk, behind the ears, inner thighs, perineum, scrotum (A-C), and periorbital edema with signs of bilateral dry conjunctivitis (D) in a patient on day 5 of illness. Published with the parents’ permission.

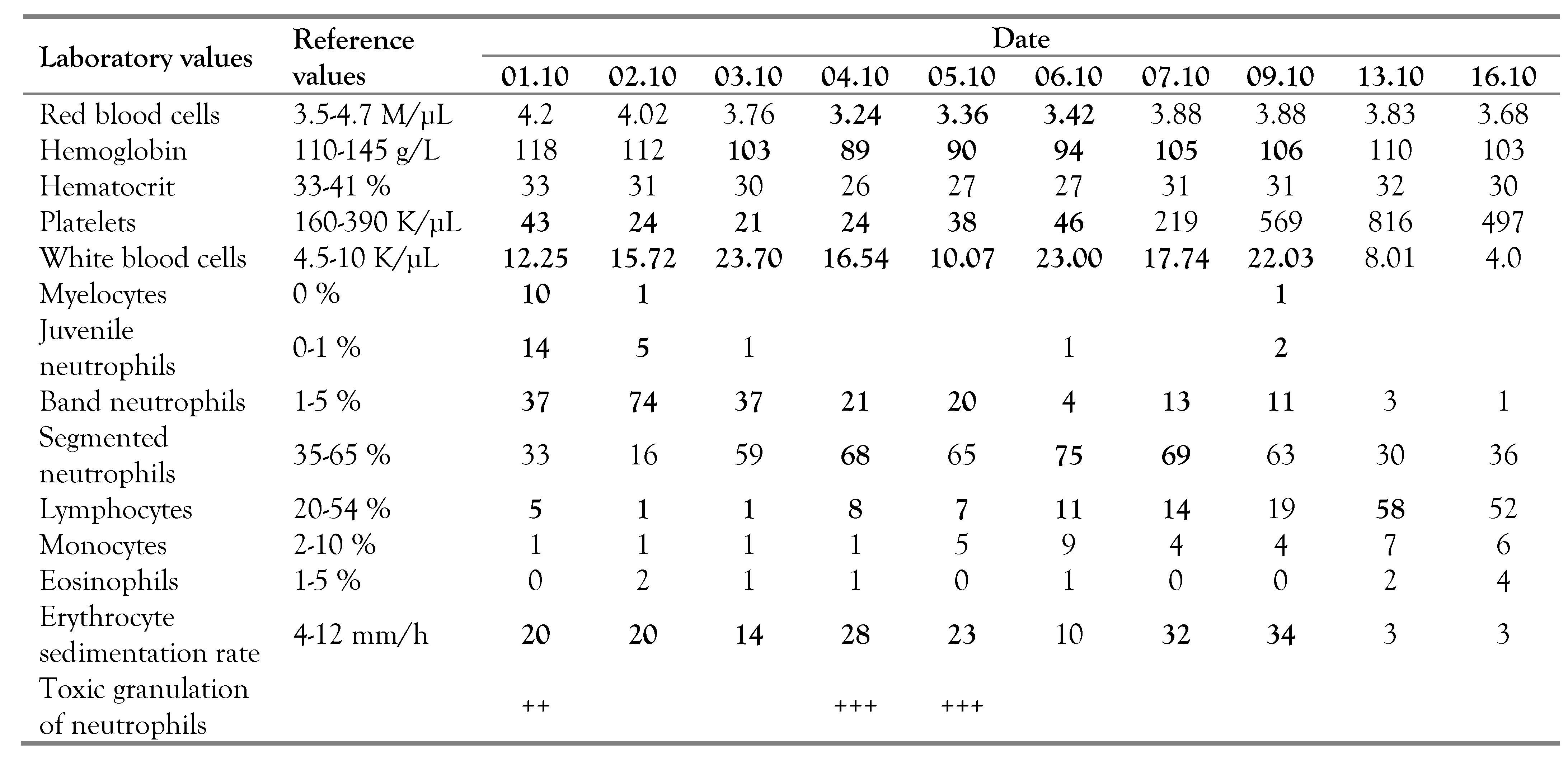

The child underwent a thorough comprehensive laboratory examination in the dynamics of the disease. The laboratory examination revealed signs of anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis with a left shift of the formula and lymphopenia, increased ESR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dynamics of the complete blood count.

Clinical analysis of urine was characterized by hypersthenuria, leukocyturia, bilirubinuria, urobilinogenuria, and the presence of ketone bodies.

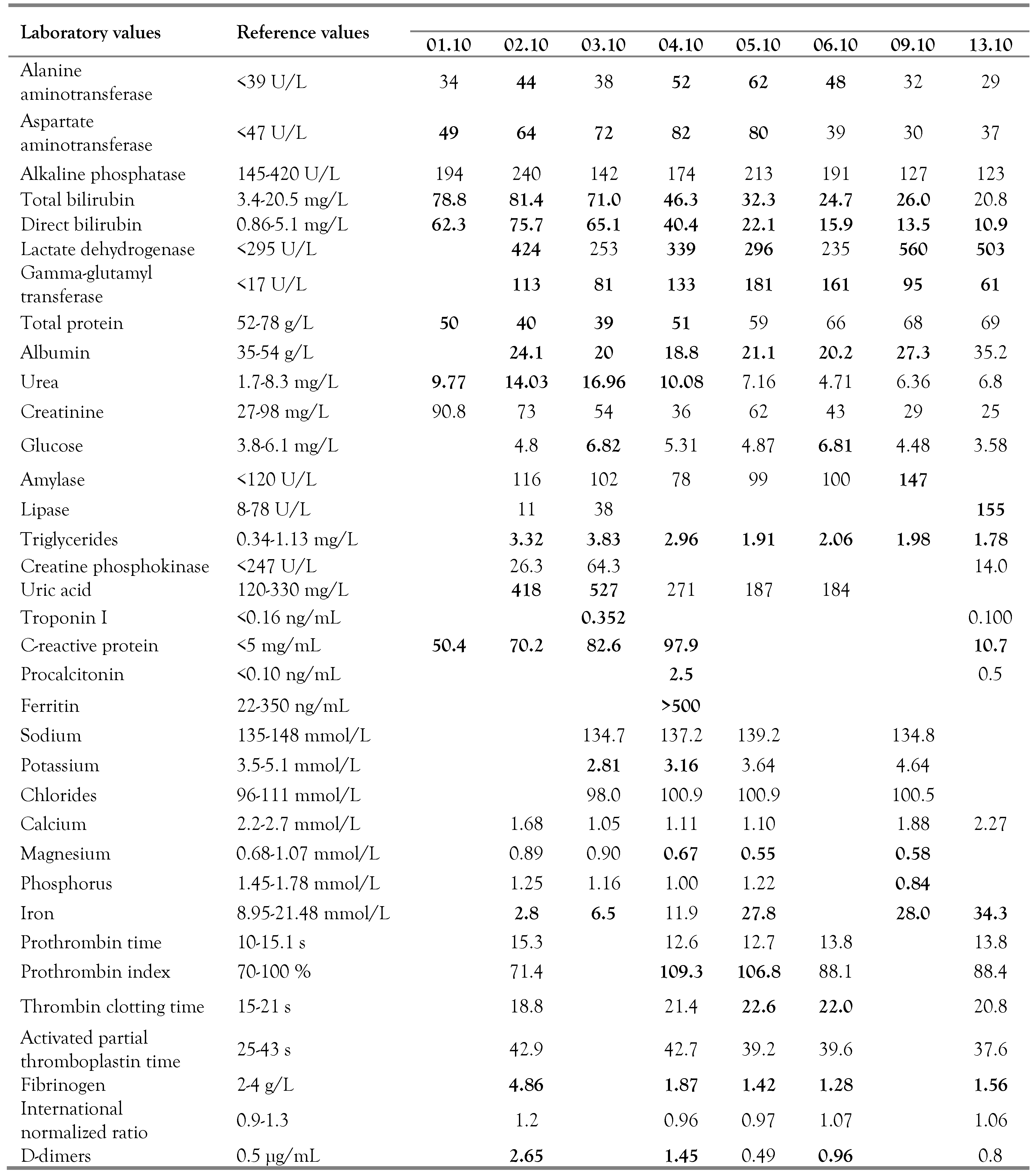

Biochemical tests showed high levels of enzymes, direct hyperbilirubinemia, signs of hypoproteinemia with hypoalbuminemia, increased levels of urea, triglycerides, and uric acid. There was a significant increase in the level of C-reactive protein, troponin, procalcitonin, and blood ferritin. There were also electrolyte disturbances with hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and pathological violations in iron concentration in the dynamics of the disease.

Based on the coagulogram data, signs of disseminated intravascular hypercoagulation with increased prothrombin index, prolonged thrombin time, increased concentration of fibrinogen, and D-dimers were revealed. Summarized data of biochemical analysis of blood and coagulogram of the patient are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dynamics of biochemical blood analysis and coagulation tests.

To rule out sepsis, pseudotuberculosis, and streptococcal infection, the following tests were performed: blood culture tests (negative), agglutination tests for Yersinia pseudotuberculosis antibody (negative), and throat swab cultures (negative).

According to the current epidemiological situation in the region, the boy and his mother were examined for the presence of coronavirus infection by PCR and serological methods for qualitative estimation of specific antibodies. PCR results of throat/nose swabs for SARS-CoV-2 in this child were negative (twice within 7 days), while in mother they were positive, then in 7 days – negative. Immunoenzyme analysis (ELISA) on the 2nd day of admission showed the absence of IgM to SARS-CoV-2 and elevation of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 up to 10.42.

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen on the day of admission revealed signs of hepatomegaly (transverse diameter –117 mm), splenomegaly (91×46 mm), increased echogenicity of the liver and pancreas. The presence of free fluid behind the liver up to 20 mm and in the right renal angle up to 7 mm was detected. Repeated ultrasound examination within 7 days was characterized by positive dynamics with a gradual decrease in pathological symptoms.

By echocardioscopy at the beginning of the disease and in dynamics (7th-14th days of hospitalization) pathological changes in the heart, main vessels, or signs of pulmonary hypertension were not detected.

Chest radiography on the 9th day of the disease did not detect pathology of the respiratory system.

Given the data of epidemiological history, the presence of hyperthermia, intoxication, meningeal syndrome, exanthema, bilateral non- purulent conjunctivitis, acute gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain), and laboratory abnormalities, based on the criteria developed by the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, the child was diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporary associated with Sars-CoV-2 [9]. On the day of admission, the patient was prescribed antibiotics (ceftriaxone and amikacin), infusion therapy (5% glucose, 0.9% sodium chloride, rheosorbilact, 4% potassium chloride, 10% albumin), diuretics (furosemide), and symptomatic drugs in age-appropriate doses. On the 3rd day, due to rapid progression of infectious-toxic changes, continuing increase of inflammatory markers, the antibiotic was changed to meropenem (880 mg TID, 10 days), the boy was administered an intravenous immunoglobulin infusion of 2 g/kg twice and dexamethasone 6 mg/day for 5 days. From the 7th day of hospitalization, the patient received anticoagulants (heparin 250 IU QID, 8 days) and acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg, daily). The dynamics of the disease were positive. After stabilization, the patient was transferred from the PICU to the infectious diseases department on the 9th day. After the treatment, the child's condition improved – the temperature returned to normal, the signs of hyperthermia, intoxication and meningeal syndrome, manifestations of dry conjunctivitis, abdominal pain, skin rashes, and edema of the abdominal wall and feet were eliminated. Indicators of laboratory and instrumental examinations were completely normalized. The recovered child was discharged home on the 15th day of treatment under the supervision of a district pediatrician.

After discharge home, the child was prescribed to continue taking acetylsalicylic acid for up to two months under the control of a blood test every 2 weeks. To assess the negative effects of infection on the cardiovascular system, regular evaluation of electrocardiogram parameters and echocardioscopy once a month for 2 months was recommended. To date, all indicators of the child's health remain normal, the child continues to be under our supervision.

Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a new delayed inflammatory syndrome, with potentially severe evolution, has been described in the pediatric population of children and adolescents, a population previously considered less vulnerable to the severe forms of COVID-19.

The first case of SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive in a 6-month-old girl with fever, Kawasaki disease, and minimal respiratory symptoms was reported in April 2020.8 On 25 April 2020, the United Kingdom's National Health Service has issued a warning to doctors about an unusual disorder – multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, which had the characteristics of Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome with damage to the heart and gastrointestinal tract. To date, the actual incidence of MIS-C remains unknown, because children are tested less frequently than adults, most of those with acute COVID-19 have mild symptoms, and MIS-C may follow either COVID-19 or asymptomatic infection. Nevertheless, the number of such patients continues to grow around the World [4,6].

Based on the aggregate data, the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health in London, [9] the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and the Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS) have issued clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of MIS-C.

At present, MIS-C is defined as a systemic disease characterized by long-term fever, multiorgan dysfunction, laboratory evidence of hyperinflammation, positive SARS-CoV-2 tests, and the absence of an alternative cause that explains the clinical picture. The presence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, a specific T-cell response, and delayed development after the acute phase of infection indicates the potential role of acquired immunity and anti-inflammatory response mediated by antibodies or immune complexes. In severe cases, impaired regulated immune response can lead to an increase in the number of overactive macrophages, increased production of cytokines and chemokines, similar to those observed in macrophage activation syndrome [10].

Despite the growing number of reported cases, numerous questions about pathophysiological, epidemiological, and clinical features associated with the potentially severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome COVID-19, especially in children are still present. Perhaps the most controversial issue is the differential diagnosis of Kawasaki disease because both pathologies are hyperinfectious syndrome complexes with a wide range of clinical phenotypes and varying degrees of complications. Blood vessels are thought to be the main target of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, resulting in inflammation and endothelial damage, reflecting the immunobiological changes found in Kawasaki disease. At the same time, even if the pathophysiology of MIS-C has not yet been thoroughly studied, it has several distinct clinical features – children are usually older than 5 years, characterized by cytopenia, elevated circulating ferritin (as marker of inflammation), D-dimers and troponin (markers of cardiovascular lesions), transient liver, myocardial dysfunction, and shock, which are less common in Kawasaki disease [11].

The question of the importance and necessity of confirming the connection between multisystem inflammatory syndrome and infection with the new coronavirus COVID-19 also remains interesting and controversial. Today, it is thought that although MIS-C is epidemiologically related to COVID-19, not all cases require evidence of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. MIS-C appears to be the result of a post-acute immunological reaction to an initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, so in most cases RT-PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swabs is negative, but there is serological evidence of disease, positive IgG for SARS-CoV-2 [11]. There are a number of hypotheses for why children would develop MIS- C among which: multiple exposure to SARS- CoV-2 with parents with COVID-19 can work as a priming of the immune system in genetically predisposed persons, or previous exposure to infections with other coronaviruses, which are more common in the pediatric population, would lead to abnormal reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. Therefore, according to the recommendations of the Royal College of London, the criteria for association with COVID- 19 are considered to be suspected or confirmed acute coronavirus infection 4-6 weeks before the development of multisystem inflammatory syndrome, probable contact with a patient with COVID-19, as well as living in areas with adverse epidemiological situation [9].

As there are currently no generally accepted guidelines for the treatment of MIS-C, it is recommended to use an individualized multidisciplinary group approach, given the wide range of possible disorders and the need for their correction [13]. Treatment response should be guided by serial clinical, laboratory, and instrumental assessments.

Conclusions

This clinical case draws the attention of general practitioners and pediatricians to the importance of timely diagnosis of a rare, but potentially severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporarily associated with COVID-19 in children.

Taking into account the appearance of new pathology in pediatric practice and lack of sufficient information on the clinical and pathogenic features of the new disease, a careful scientific approach to collecting and analyzing data on each detected case using the recommendations of the internationally agreed definitions will improve the diagnosis and optimize the treatment.

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family for publication of this case report and images.

Author Contributions

All authors are responsible for reported research and all authors have participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting or revising of the manuscript. HP, OD, VS, and IH: conceptualization and methodology. HP and OD: resources. HP, OD and IH: data curation. HP and VS: analysis. HP and VS: writing – original draft preparation, review and editing. HP: supervision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the patient and his parents for their willingness to share this case and the images. The authors thank all the members of the healthcare team who contributed to the managing of the patient reported in this case.

Conflicts of interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report 190. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Information on the spread of coronavirus infection 2019-nCoV. Available online: https://moz.gov.ua/article/news/operativna-informacija-pro-poshirennja-koronavirusnoi-infekcii-2019-cov19 (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Bhuiyan, M.U.; Stiboy, E.; Hassan, M.Z.; et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021, 39, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parri, N.; Lenge, M.; Cantoni, B.; et al. COVID-19 in 17 Italian pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2020, 146, e20201235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malviya, A.; Mishra, A. Childhood multisystem inflammatory syndrome: an emerging disease with prominent cardiovascular involvement-a scoping review. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuhara, J.; Watanabe, K.; Takagi, H.; Sumitomo, N.; Kuno, T. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ternopil Regional Laboratory Center of Ministry of Health. Information on the spread of coronavirus infection 2019-nCoV in Ternopil region. Available online: http://terses.gov.ua/index.php (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Jones, V.G.; Mills, M.; Suarez, D.; et al. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020, 10, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Guidance: Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19. London (UK): Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2020. Available online: www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/guidance-paediatric- multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-temporally-associated-covid-19 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Berard, R.A.; Scuccimarri, R.; Haddad, E.M.; et al.; Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 Ottawa: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020. Available online: www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/pims (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Whittaker, E.; Bamford, A.; Kenny, J.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020, 324, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Riitano, F.; Valentini, P. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally related with SARS-CoV-2: immunological similarities with acute rheumatic fever and toxic shock syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2020, 8, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, R.; Allin, B.; Jones, C.E.; et al. A national consensus management pathway for paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS-TS): results of a national Delphi process. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021, 5, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2021.