Molecular Study of Human Astrovirus in Egyptian Children with Acute Gastroenteritis

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Molecular study of astrovirus

Extraction of RNA from stool samples

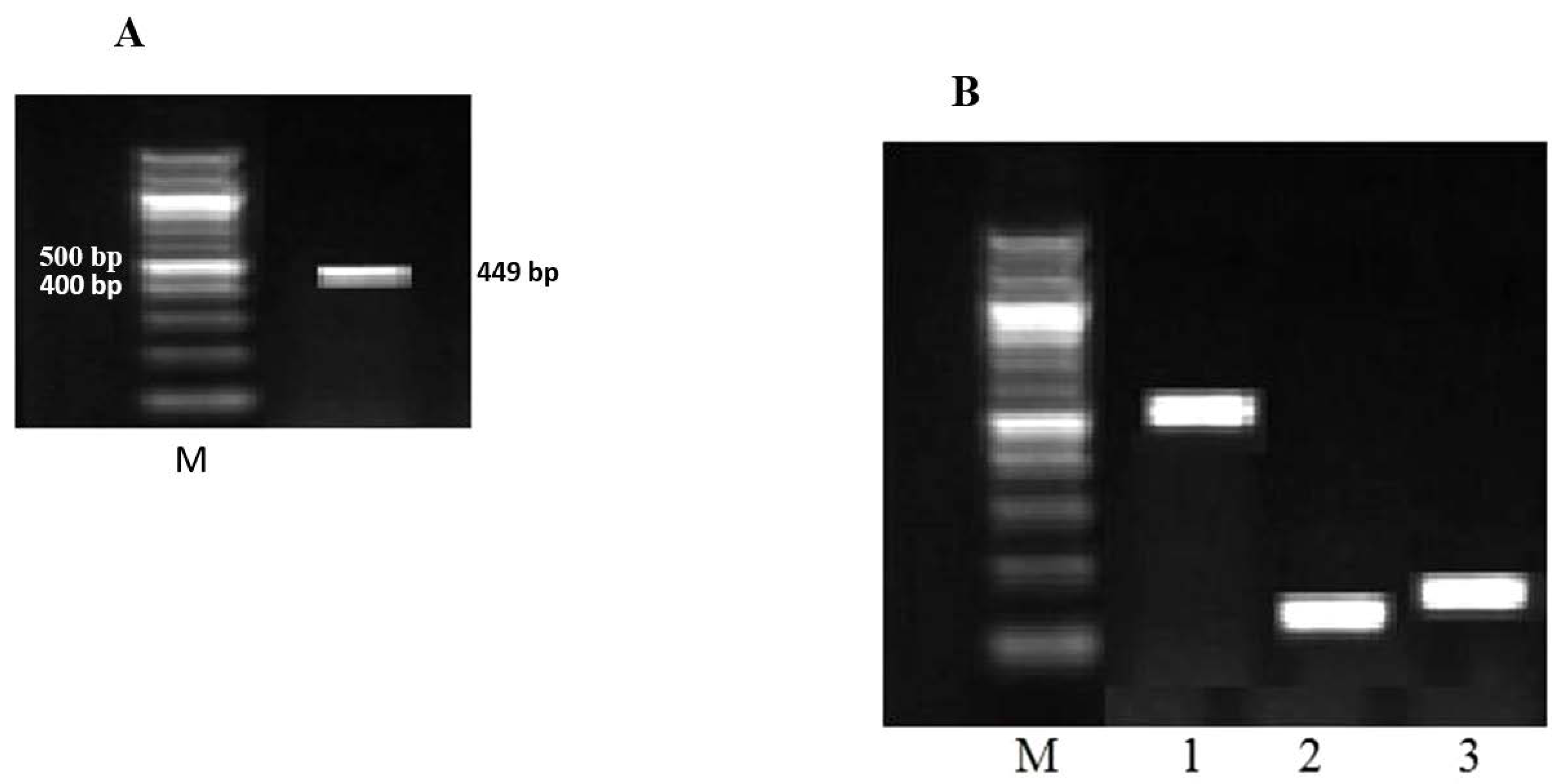

Detection of astrovirus by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Genotyping of astrovirus by multiplex nested/RT-PCR

Statistical analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2016 Diarrhoeal Disease Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. In World Health Statistics; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 43–53.

- Guerrant, R.L.; DeBoer, M.D.; Moore, S.R.; Scharf, R.J.; Lima, A.A. The impoverished gut-a triple burden of diarrhoea, stunting and chronic disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013, 10, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.M.; Leung, A.K.; Hon, K.L. Acute gastroenteritis: from guidelines to real life. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010, 3, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, W.H.; Walsh, J.F.; Kotch, J.B.; Weber, D.J.; Gunn, E.; Vinjé, J. Prospective study of etiologic agents of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in child care centers. J Pediatr. 2009, 154, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.L.; Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Guix, S. Epidemiology of classic and novel human astrovirus: gastroenteritis and beyond. Viruses. 2017, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, P.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Burnham, A.; Cattoli, G. Astrovirus infections in humans and animals-molecular biology, genetic diversity, and interspecies transmissions. Infect Genet Evol. 2011, 11, 1529–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelaw, A.; Pietsch, C.; Liebert, U.G. Genetic diversity of human adenovirus and human astrovirus in children with acute gastroenteritis in Northwest Ethiopia. Arch Virol. 2019, 164, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.K.; Glass, R.; Bresee, J.S.; Duggan, C.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children; oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003, 52, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, J.S.; Lee, T.W.; Kurtz, J.B.; Glass, R.I.; Monroe, S.S. Typing of human astroviruses from clinical isolates by enzyme immunoassay and nucleotide sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Negishi, H.; Wang, Q.H. , et al. Molecular epidemiology of astroviruses in Japan from 1995 to 1998 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction with serotype-specific primers (1 to 8). J Med Virol. 2000, 61, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliopoulos, V.A.; Marvin, S.A.; Freiden, P. , et al. Oral administration of astrovirus capsid protein is sufficient to induce acute diarrhea in vivo. mBio. 2016, 7, e01494–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguekeng Tsague, B.; Mikounou Louya, V.; Ntoumi, F. , et al. Occurrence of human astrovirus associated with gastroenteritis among Congolese children in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Int J Infect Dis. 2020, 95, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdag, A.I.; Gupta, S.; Khan, N.; Upadhayay, A.; Ray, P. Epidemiology and clinical features of rotavirus, adenovirus, and astrovirus infections and coinfections in children with acute gastroenteritis prior to rotavirus vaccine introduction in Meerut, North India. J Med Virol. 2019, 92, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiulia, N.M.; Mwenda, J.M.; Nyachieo, A.; Nyaundi, J.K.; Steele, A.D.; Taylor, M.B. Astrovirus infection in young Kenyan children with diarrhoea. J Trop Pediatr. 2007, 53, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- El Taweel, A.; Kandeil, A.; Barakat, A.; Alfaroq Rabiee, O.; Kayali, G.; Ali, M.A. Diversity of astroviruses circulating in humans, bats, and wild birds in Egypt. Viruses. 2020, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayolabi, C.; Ojo, D.; Akpan, I. Astrovirus infection in children in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Infect Dis. 2012, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bergallo, M.; Galliano, I.; Daprà, V.; Rassu, M.; Montanari, P.; Tovo, P.-A. Molecular detection of human astrovirus in children with gastroenteritis, northern Italy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018, 37, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidokhti, M.R.; Ullman, K.; Hammer, A.S. , et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy evaluation of subunit astrovirus vaccines. Vaccines. 2019, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naficy, A.B.; Rao, M.R.; Holmes, J.L. , et al. Astrovirus diarrhea in Egyptian children. J Infect Dis. 2000, 182, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, F.; Fascia, P.; Dauvergne, M. , et al. Prevalence of group A rotavirus, human calicivirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus type 40 and 41 infections among children with acute gastroenteritis in Dijon, France. J Clin Microbiol. 1999, 37, 3055–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guix, S.; Caballero, S.; Villena, C. , et al. Molecular epidemiology of astrovirus infection in Barcelona, Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2002, 40, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olortegui, M.P.; Rouhani, S.; Yori, P.P. , et al. Astrovirus infection and diarrhea in 8 countries. Pediatrics. 2018, 141, e20171326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, A.; Guix, S.; Pintó, R.M. Epidemiology of human astroviruses. In: Schultz-Cherry S, editor. Astrovirus research: essential ideas, everyday impacts, future directions: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. p 1-18.

- Kang, Y.H.; Park, Y.K.; Ahn, J.B.; Yeun, J.D.; Jee, Y.M. Identification of human astrovirus infections from stool samples with diarrhea in Korea. Arch Virol. 2002, 147, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, F.; Lizasoain, A.; Victoria, M. , et al. Epidemiology and genetic diversity of classic human astrovirus among hospitalized children with acute gastroenteritis in Uruguay. J Med Virol. 2017, 89, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H.; Palombo, E.A.; Bishop, R.F. Epidemiology of astrovirus infection in young children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Melbourne, Australia, over a period of four consecutive years, 1995 to 1998. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, N.A.; Dove, W.; Gondwe, J.S. , et al. Detection and characterisation of human astroviruses in children with acute gastroenteritis in Blantyre, Malawi. J Med Virol. 2002, 67, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer sequence | Amplicon Size |

| ORF2 | 5'CAACTCAGGAAACAGGGTGT3' 5'TCAGATGCATTGTCATTGGT3' | 449 bp |

| AST-S1 | 5'AACCAAGGAATGACAATGAC3' | 212 bp |

| AST-S2 | 5'ACCTGCGCTGAGAAACTG3' | 158 bp |

| AST-S3 | 5'CTGCTTGCATCTGGTCTTTCA3' | 119 bp |

| AST-S4 | 5'TGATGATGAAGACTCTAA TAC3' | 258 bp |

| AST-S5 | 5'TAGTAACTTATGATAGCC3' | 388 bp |

| AST-S6 | 5'TGGCCACCCTTGTTCCTCAGA3' | 427 bp |

| AST-S7 | 5'CTAGACAACAACACCCCG3' | 548 bp |

| AST-S8 | 5'GGTAAGTGGTACCTGCTAACTAG3' | 599 bp |

| 3' end of the capsid | 5'TCCTACTCGGCGTGGCCGC3' |

| Total patients | Astrovirus positive | Astrovirus negative | P value | ||

| (N=100), n (%) | (N=11), n (%) | (N=89), n (%) | |||

| Sex | 0.519a | ||||

| Male | 58 (58) | 5 (45.5) | 53 (59.6) | ||

| Female | 42 (42) | 6 (54.5) | 36 (40.4) | ||

| Age | 0.005* | ||||

| Median | 1 year | 6 months | 1 year | ||

| (min-max) 25th percentiles 75th percentiles | 3 months - 7 years 1 year 3 years | 3 months - 3 years 3 months 7 months | 3 months - 7 years 1 year 3 years | ||

| Season distribution | |||||

| Warm seasons | Summer | 45 (45) | 10 (90.9) | 35 (39.3) | 0.025** |

| Spring | 29 (29) | 1 (0.9) | 28 (31.5) | ||

| Cold seasons | Winter | 12 (12) | - | 12 (7.9) | |

| Autumn | 14 (14) | - | 14 (15.7) | ||

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 58 (58) | 11 (100) | 47 (52.8) | 0.002** | |

| Urban | 42 (42) | - | 42 (100) | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 38 (38) | 7 (63.6) | 31 (34.8) | 0.753b | |

| Fever | 58 (58) | 10 (90.9) | 48 (35.9) | 0.017** | |

| Dehydration degree Mild | 49 (49) | 5 (45.4) | 44 (49.4) | 0.463b | |

| Moderate | 36 (36) | 3 (27.3) | 33 (37.1) | ||

| Severe | 15 (15) | 3 (27.3) | 12 (13.5) | ||

| Age group (years) | Total | |||||||

| ≤1.00 | 1-2 | 2-3 | 3-4 | 4-5 | 5-7 | |||

| PCR | Positive | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Negative | 50 | 4 | 20 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 89 | |

| Total | 59 | 5 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 100 | |

© GERMS 2020.

Share and Cite

Zaki, M.E.S.; Mashaly, G.E.-S.; Alsayed, M.A.L.; Nomir, M.M. Molecular Study of Human Astrovirus in Egyptian Children with Acute Gastroenteritis. Germs 2020, 10, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2020.1202

Zaki MES, Mashaly GE-S, Alsayed MAL, Nomir MM. Molecular Study of Human Astrovirus in Egyptian Children with Acute Gastroenteritis. Germs. 2020; 10(3):167-173. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2020.1202

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaki, Maysaa El Sayed, Ghada El-Saeed Mashaly, Mona Abdel Latif Alsayed, and Manal Mahmoud Nomir. 2020. "Molecular Study of Human Astrovirus in Egyptian Children with Acute Gastroenteritis" Germs 10, no. 3: 167-173. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2020.1202

APA StyleZaki, M. E. S., Mashaly, G. E.-S., Alsayed, M. A. L., & Nomir, M. M. (2020). Molecular Study of Human Astrovirus in Egyptian Children with Acute Gastroenteritis. Germs, 10(3), 167-173. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2020.1202