Introduction

General danger signs are indicators of disease that have negative impact on the severe consequences of child health by increasing morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) established the Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) to focus on the assessment of general danger signs in the examination of children presenting with illness at health facilities [

1].

According to IMNCI guidelines, general danger signs of under-five childhood illnesses are categorized as: unable to breastfeed, unable to drink or eat, vomiting everything, convulsion and lethargic/unconscious. Sick children with these danger signs need rapid management and after the pre-referral treatment urgent referral is mandatory and any delay in treatment exhibits child mortality [

2].

Globally, a large number of under-five deaths occurred from preventable and treatable diseases, such as: acute respiratory infections (ARI, 7%), diarrheal diseases (12%) and febrile illnesses (14%) [

3]. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management of the general danger signs of common childhood illnesses is mandatory for reducing morbidity and mortality [

4].

Reduction in the mortality rate of under-five children is improved from 1.8% by the year of 1990–2000 to 3.9% from 2000–2015 worldwide. Global community permitted Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) at the termination of Millenium Development Goal to reduce avoidable deaths of under-five children [

3].

Now out of the 79 countries over 25 of them have under-five mortality and when the existing trend proceeds, 47 of the countries will not attain the SDG target by 2030 [

3]. To accomplish this goal in reduction of childhood mortality, mothers’ timely recognition of general danger signs of under-five child illnesses and getting appropriate medical access serve as a backbone [

1,

5].

Diarrhea, ARI and febrile illnesses are the primary causes of child mortality with the main difficulty occuring in the lowest as well as middle-income countries [

6]. Of the global under-five deaths, 98.7% have occurred in developing countries, with the highest numbers found in the South East Asian Region (SEAR) and in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) [

3,

7]. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management of the general danger signs of diarrhea, fever and ARI is crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality among under-five children [

4].

According to the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) 2016, under-five mortality declined from 116 deaths per 1000 live births from 2002–2006 to 67 deaths per 1000 live births in the year of 2012–2016 and the most common diseases of under-five children were ARI, fever and diarrhea. In the Tigrai region only 30.6% of children with ARI, 31.6% with fever and 49% of children with diarrhea received treatment from a health facility. Most neonatal deaths took place at home, thus indicating lack of an early recognition of the danger signs and low treatment-seeking practice of mothers towards modern healthcare service [

8].

In Ethiopia, to reduce under-five mortality, implementation of the IMNCI program and initiation of a number of essential public health initiatives were undertaken. Even with those activities, under-five childhood deaths are still high [

9].

The factors that affected childhood illnesses and mortality are: demographic status, economic conditions, physical, financial accessibility, disease pattern, lack of antenatal care utilization, unsupervised and poorly supervised home deliveries, health system inefficiencies, infrastructural and socio-economic constraints [

4,

10,

11,

12].

There is a scarcity of data regarding the knowledge and associated factors of childhood illnesses in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess knowledge of mothers and associated factors on general danger signs of common childhood illnesses of children under the age of five years old.

Methods

Study area and design

The study was held in Adwa town, Tigrai, Ethiopia, which is found in Central Tigrai Regional state at a distance of 977 km away from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia) and 190 kms from Mekelle (the capital city of Tigrai). A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed among mothers who had ever had sick under-five children with a history of common childhood illness in 2017.

Sample size and sampling procedure

A total of 418 mothers who had ever had sick under-five children with a history of common childhood illness were included in the study. The sample size was determined using single population proportion formula, by using 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, 10% of the non-response rate and considering 55.4% proportion of mothers’ health-seeking behaviour for common childhood illnesses [

13].

The sample size was allocated to the five kebeles of Adwa town by proportional allocation. The list of households of the under-five child with a common childhood illness six months prior to the survey was identified by health extension workers working in each kebeles and the sampling frame was made from that; by using simple random sampling method (lottery method), the sample was selected.

Data collection procedure

Interviewer based structured questionnaires were used to collect the data. Questions were suitably translated to the local language, Tigrigna and then back to English for data entry. For data collection and supervision. five diploma nurses working outside the study area and three BSc health professionals working in Adwa town were recruited accordingly. The data collectors were trained for two days on information about data collection tools, techniques, approaching participants, ethical issues and advantage of collecting the actual data.

A pre-test was conducted among the 42 (10%) mothers from Axum, a place near to Adwa with similar study population, two weeks before the actual data collection period, for its clarity, understandability and completeness, and individuals who participated in the pre-test were excluded from the actual data collection. After that, the necessary corrections and modifications were made.

Confidentiality of the participants was kept throughout the study and the supervisors were controlling the data collection process and checked the data collection tool. At the end of each day, questionnaires were reviewed and cross-checked for their completeness, accuracy and logical consistency by the principal investigator and corrective measures were undertaken.

Operational definitions

General danger signs: according to WHO standard categorized as: unable to breastfeed, unable to drink or eat, vomiting everything, convulsion, and lethargic or unconsciousness [

2].

Good knowledge on general danger signs: referred for the mothers who mentioned mean score and above of the knowledge questions (≥3 general danger signs) [

14,

15,

16].

Poor knowledge on general danger signs: referred for the mothers who mentioned below the mean score of the knowledge questions (<3 general danger signs) [

14,

15,

16].

Ever sick children with common childhood illnesses: the children had become ill with ARI, diarrhea and fever 6 months prior to the study.

Data analysis

Data were coded, entered and analysed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis was done by using frequencies and percentages. Bar graph and pie chart were used to describe the study participants in relation to relevant variables and association between independent and dependent variables were assessed using crude odds ratio with 95% confidence interval with respect to the p-value. If significant variables (p < 0.2) were detected at the bivariate logistic regression level they were entered to multivariable logistic regression.

The model of fitness was checked by Hosmer and Lemeshow test and its p-value was 0.917. Multicolinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and those with VIF greater than 10 were excluded from the model. Finally, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value less than 0.05 were considered as a significant association.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was obtained from a research ethics committee of the College of Health Sciences of Mekelle University with a reference number of 0906/2017. Official letter of cooperation was written to Tigrai Regional Health Bureau from the Department of Nursing. Support letter was obtained from the Tigrai Regional Health Bureau and Adwa Woreda health office and respective selected kebeles before field activities. Informed verbal consent was obtained from study participants. Confidentiality of results among the study participants was kept.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 416 mothers have participated with an overall response rate of 99.52%. Two mothers were excluded from the study due to critical illness.

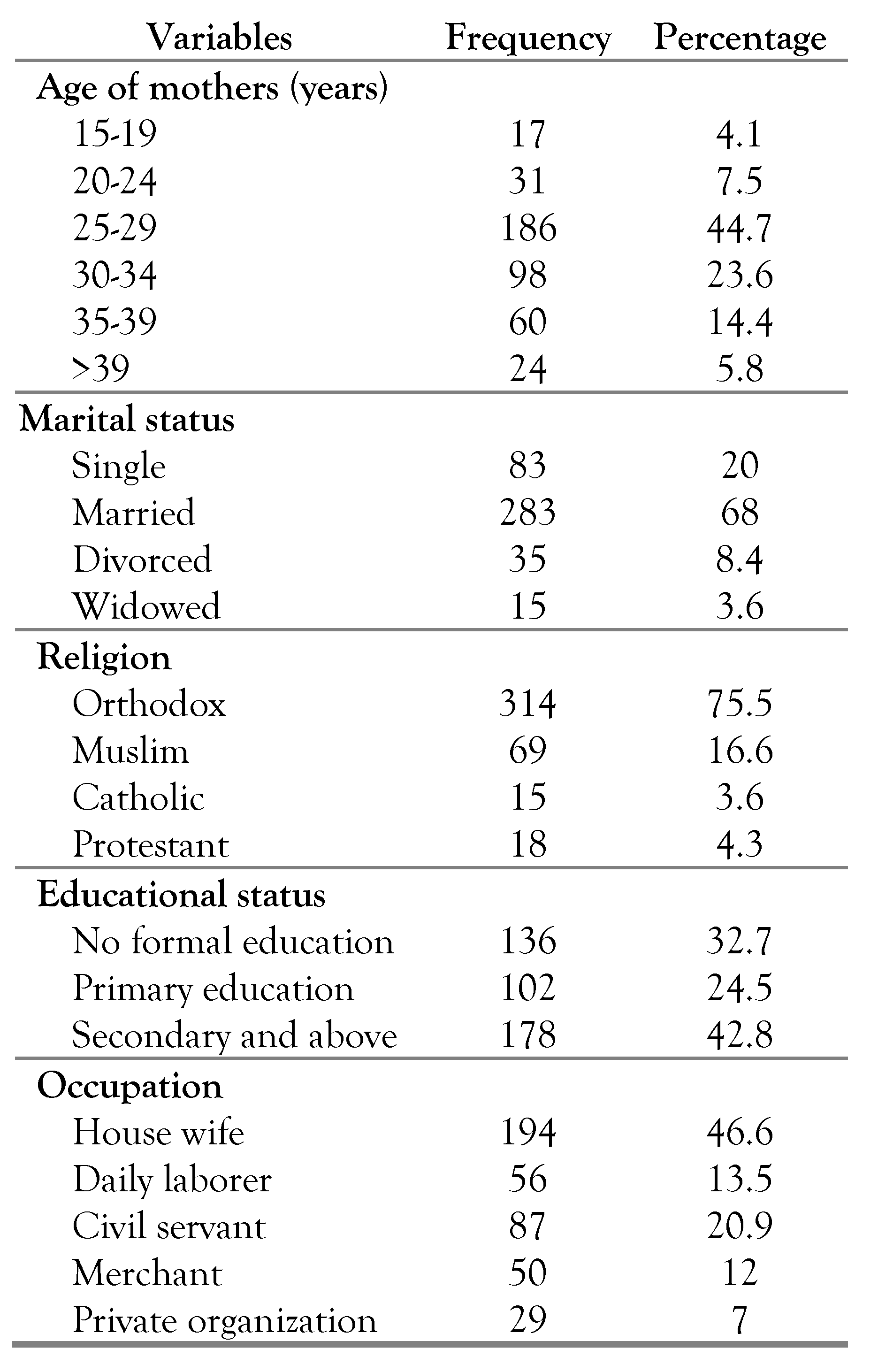

The mean age of mothers was 30.07 (standard deviation (SD) ±5.658) ranging from 16 to 49 years. One hundred and eighty-six (44.7%) of the mothers were in the age group of 25-29 years old and 283 (68%) of the participants were married (

Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of under-five children

Out of 416 mothers, 157 (37.7%) mothers had a child in the age group of less than 12 months. About half of the children 213 (51.2%) were males (

Table 2).

Childhood illnesses of under-five children

Of the total 416 sick children with childhood illnesses 6 months prior to the study, 78.6% of the children experienced two or more symptoms of those common childhood illnesses (

Table 3).

Knowledge of mothers on general danger signs of common childhood illnesses of under-five children

Concerning WHO standard general danger signs of common childhood illnesses, vomiting everything 305 (73.3%) was the most commonly mentioned danger sign. The mothers who mentioned 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 WHO standard general danger signs of common childhood illnesses of under-five children were 40 (9.6%), 190 (45.7%), 23 (5.5%), 81 (19.5%), 57 (13.7%) and 25 (6%) respectively (

Table 4).

On the other hand, among the 19 (4.6%) non-WHO standard general danger signs (others); 6 (31.6%) of the respondents mentioned eye problem, 2 (10.5%) ear problem, 2 (10.5%) low body temperature, 7 (36.8%) irritability, 1 (5.3%) tonsillitis and 1 (5.3%) constipation mentioned as a key general danger signs of under-five child illnesses (

Table 4).

Regarding mothers’ knowledge, more than half of them, 230 (55.3%) had poor knowledge of WHO standard general danger signs of common childhood illnesses (

Fig 1).

Factors associated with knowledge of mothers for general danger signs of common childhood illnesses

Variables with a p-value less than or equal to 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered to the multivariable logistic regression model: educational status of mothers, childbirth order, occupation of mothers and source of information were found to be significantly associated with knowledge of mothers on general danger sign of under-five common childhood illnesses.

Mothers with primary education were 1.93 times more likely to know about general danger signs than mothers who were illiterate (AOR = 1.93, 95%CI = 1.09–3.44, p = 0.025). Mothers with occupational status of governmental and non-governmental employees were 5.94 and 2.29 times more likely to know about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than housewives (AOR = 5.94, 95%CI = 3.17–11.12, p ≤ 0.001 and AOR = 2.29, 95%CI = 1.19–4.42, p = 0.014, respectively).

Mothers having an under-five child in the birth order of more than three children were 1.85 times more likely to know about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than those mothers who had only one child (AOR = 1.85, 95%CI = 1.00–3.40,

p = 0.005). Mothers who get information about general danger signs of under-five children common childhood illnesses from healthcare providers were 2.19 times more likely to have knowledge than the mothers who get experience from their previous child (AOR = 2.19, 95%CI = 1.23–3.87,

p = 0.007) –

Table 5.

Discussion

A sick child with general danger signs of common childhood illnesses needs management since a delay in seeking care results in disability and child mortality [

2]. This community-based study aimed to assess knowledge of mothers and its associated factors on general danger signs of common childhood illnesses of children under the age of five years old in Adwa town.

In this study, 55.3% of the mothers had poor knowledge of WHO standard general danger signs of common childhood illnesses. This knowledge level is higher when compared with previous studies conducted in North West of Ethiopia (18.2%), Gedeo zone (32.4%) and Southwestern Rural Uganda (14.8%) [

10,

17,

18]. This discrepancy may be due to variation in sample size, time gap, residence, socio-economic and cultural variation.

This study demonstrated that educational status and occupation of mothers, childbirth order and source of information were significantly associated with the level of knowledge on general danger signs of common childhood illnesses among mothers.

Mothers with primary education were about 2 times more likely to be knowledgeable about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than mothers who were illiterate (AOR = 1.93, 95%CI = 1.09–3.44,

p = 0.025). This is consistent with a study conducted in Woldia and North West of Ethiopia [

10,

19]. This may be due to: educated mothers acquire knowledge about the danger signs of childhood illnesses and human health through their academic life. Furthermore, educated mothers were more likely to make a decision on looking quality of health service and have a better perception of danger signs of common childhood illnesses.

Mothers with occupational status of government employee were 5.94 times more likely to know about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than housewives (AOR = 5.94, 95%CI = 3.17–11.12, p ≤ 0.001) and nongovernmental organization (NGO) employed mothers were 2.29 times more likely to know about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than housewives (AOR = 2.29, 95%CI = 1.19–4.42, p = 0.014). The possible justification might be due to: governmental and NGO employee mothers may share different experiences in their workplace concerning the knowledge of life-threatening conditions of childhood illnesses with other mothers.

Mothers having an under-five child in the birth order of more than three children were 1.85 times more likely to know about general danger signs of common childhood illnesses than mothers who had only one child (AOR = 1.85, 95%CI = 1.00–3.40, p = 0.005). This might be through acquiring knowledge of the danger signs of the children’s illnesses through their experience of their previous children.

Mothers who get information about general danger signs of under-five children common childhood illnesses from healthcare providers were 2.19 times more likely to have knowledge than the mothers who get experience from previous child (AOR = 2.19, 95%CI = 1.23–3.87, p = 0.007). This may be due to: healthcare providers have a better knowledge concerning health issues better than anybody else because of their profession, taking updated information through different trainings and their life experiences.

The global and national integrated management of common newborn and childhood illnesses are established to improve the vertical and horizontal integration, addressing the main gaps in process of the quality of the healthcare system, providing consistent delivery of high impact clinical interventions and optimizing care as well as reducing unnecessary treatment to danger signs of childhood diseases [

20]. Many of the concerns are related to the lack of knowledge of mothers on the danger signs of childhood illnesses.

This study also had some limitations. Morbidity data of the children was collected without the validation of medical personnel only by the mothers’ perception. This study used a recall period of six months. This may be susceptible to recall bias and social desirability bias. Since the study was cross-sectional, it may not be strong to show direct cause and effect relationship but may only indicate a temporal relationship.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study, 55.3% of the mothers had poor knowledge of WHO standard general danger signs of common childhood illnesses. Educational status of mothers, childbirth order, source of information and occupation of mothers were significantly associated with knowledge of mothers on general danger signs of under-five common childhood illnesses.

Therefore, health education, support and counselling should be given to community, particularly to women in health visits, religious and meetings about early recognition of general danger signs of common childhood illnesses, efforts expected to be done by government and non-governmental organization to improve the mothers’ knowledge by providing information, education and behavioral change communication in order to improve their ability to recognize danger signs of common childhood illnesses and improved literacy, women empowerment and health education are strategies that may improve.

Author Contributions

S.G. carried out the conception and designing of the study, performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. G.W., B.B. and B.G. supervised the data collection and assisted the analysis. B.F. assisted with interpretation of the data and reviewed the manuscript critically. T.T. and H.N. critically reviewed the manuscript and made progressive suggestions throughout the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their heart full gratitude for the Mekelle University College of Health Science, Department of Nursing for providing such a professional career. For the last, not the least, the deepest gratitude also extends to the Tigray Regional Health Bureau and Adwa Woreda Health Bureau administrators, study participants, data collectors and supervisors for their necessary collaboration.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Young Infants Clinical Signs Study Group. Clinical signs that predict severe illness in children under age 2 months: a multicentre study. Lancet 2008, 371, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses; IMCI fact sheet 2; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, World Bank, United Nations Population Division. Levels & trends in child mortality; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar-ul-Haq, H.; Kumar, R.; Durrani, S.M. Recognizing the danger signs and health seeking behaviour of mothers in childhood illness in Karachi, Pakistan. Univers J Public Health 2015, 3, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin, C.J.; Smith, H.J.; Swartz, A.; et al. Understanding careseeking for child illness in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework based on qualitative research of household recognition and response to child diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Soc Sci Med 2013, 86, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldsetzer, P.; Williams, T.C.; Kirolos, A.; et al. The recognition of and care seeking behavior for childhood illness in developing countries. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. Maternal mortality. 2019. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/maternal-mortality (accessed on day month year).

- WHO, UNICEF. Countdown to 2015: Accountability for maternal, newborn and child survival; WHO, UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nigatu, G.; Worku, G.; Dadi, F. Level of mother’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in north-west of Ethiopia: a community-based study. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doracaj, D.; Grabocka, E.; Hallkaj, E.; Vyshka, G. Healthcare-seeking practices for common childhood illnesses in northeastern Albania: A community-based household survey. J Adv Med Pharm Sci 2015, 3, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisso, M.; Addisu, Y.; Vata, P.; Berhanu, Y. Danger signs of neonatal and postnatal illness and health-seeking behaviour among pregnant and postpartum mother in Gedeo zone. J Curr Res 2015, 8, 25466–25471. [Google Scholar]

- Kolola, T.; Gezahegn, T.; Addisie, M. Health care seeking behavior for common childhood illnesses in Jeldu District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekwochi, U.; Ndu, I.; Osuorah, C.; et al. Knowledge of danger signs in newborns and health-seeking practices of mothers and caregivers in Enugu state, South-East Nigeria. Ital J Pediatr 2015, 41, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigbokhaode, A.Q.; Isah, E.C.; Isara, A.R. Health seeking behaviour among caregivers of under-five children in Edo State, Nigeria. South East Eur J Public Health. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibaru, E.G.; Otara, A.M. Knowledge of neonatal danger signs among mothers attending the well-baby clinic in Nakuru Central District, Kenya: cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Res Notes 2016, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, J.; Odberg Pettersson, K.; Asp, G.; Kabakyenga, J.; Agardh, A. Inadequate knowledge of neonatal danger signs among recently delivered women in southwestern rural Uganda: a community survey. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisso, M.; Addisu, Y.; Prabhanja. Danger signs of neonatal and postnatal illness and health-seeking 2015. J Curr Res 2015, 8, 25466–25471. [Google Scholar]

- Jemberia, M.M.; Berhe, E.T.; Mirkena, H.B.; Gishen, D.M.; Tegegne, A.E.; Reta, M.A. Low level of knowledge about neonatal danger signs and its associated factors among postnatal mothers attending at Woldia general hospital, Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 2018, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistashvili, T.; Rahimzai, M.; Mwanja, N.; Cherkezishvili, E. Improved integrated management of newborn and childhood illnesses in Northern Uganda. Int J Integr Care 2017, 17, A34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]