Relationship Between Microbiological and Physicochemical Parameters in Water Bodies in Urabá, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

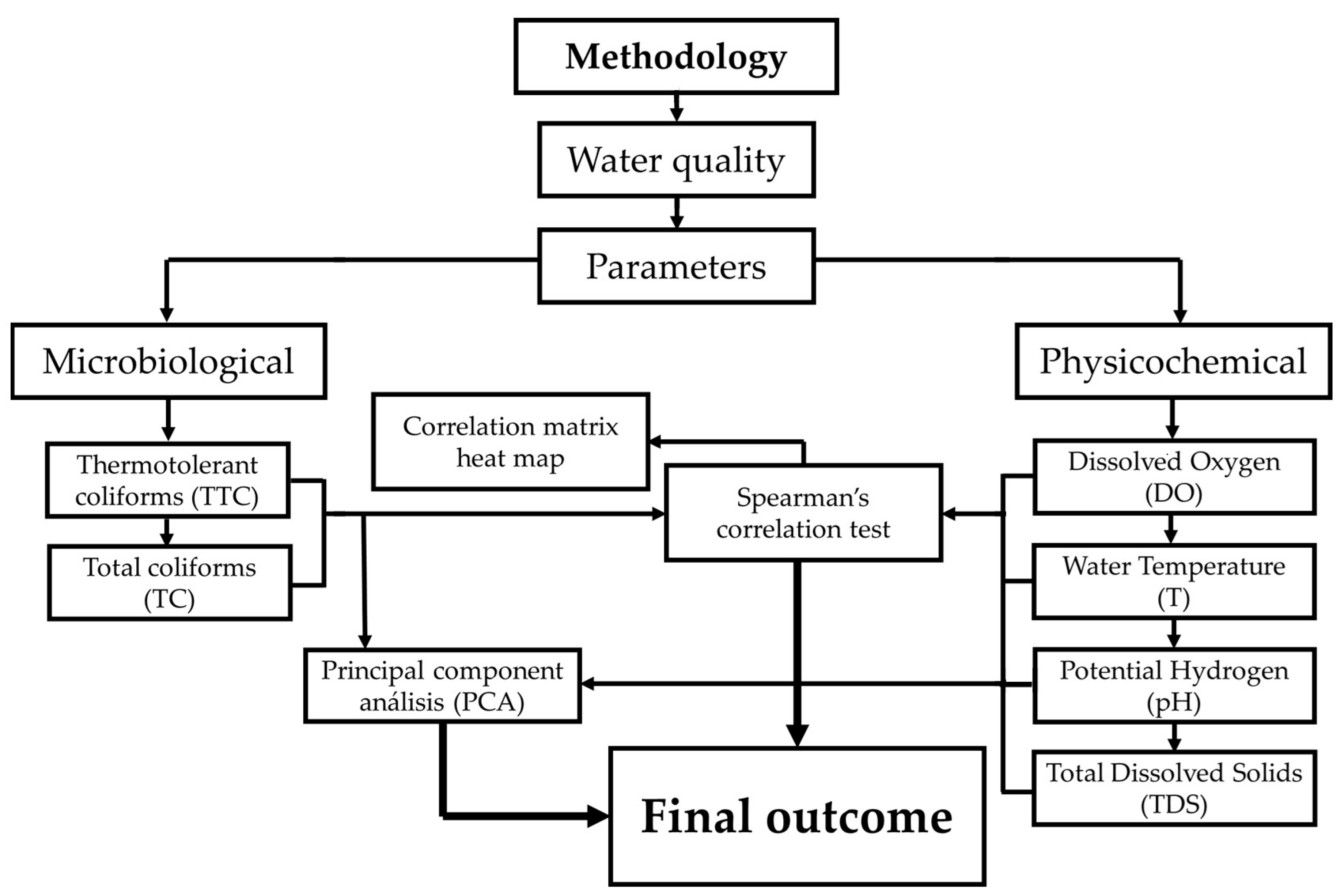

2. Materials and Methods

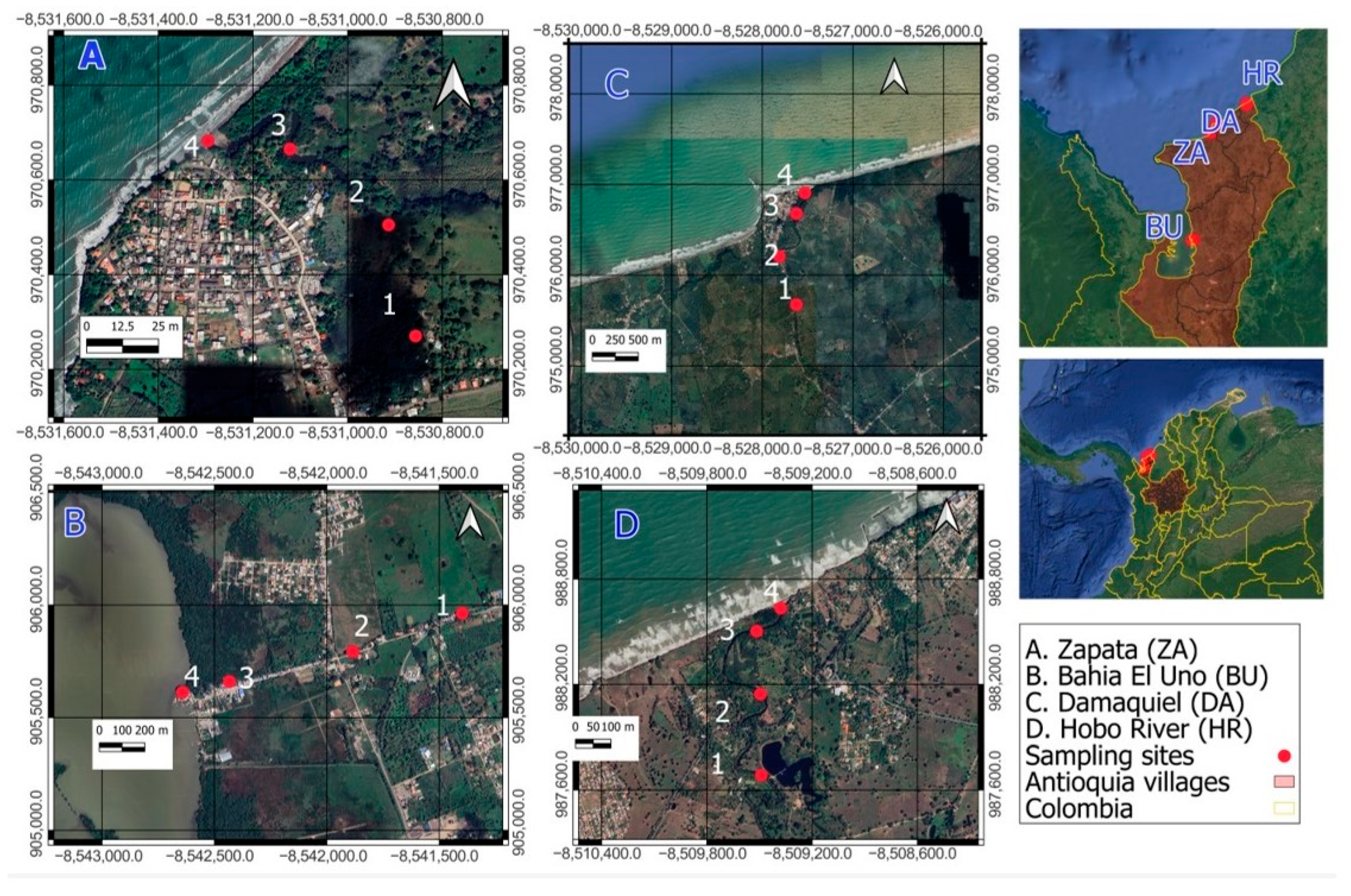

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Analytical Protocols

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

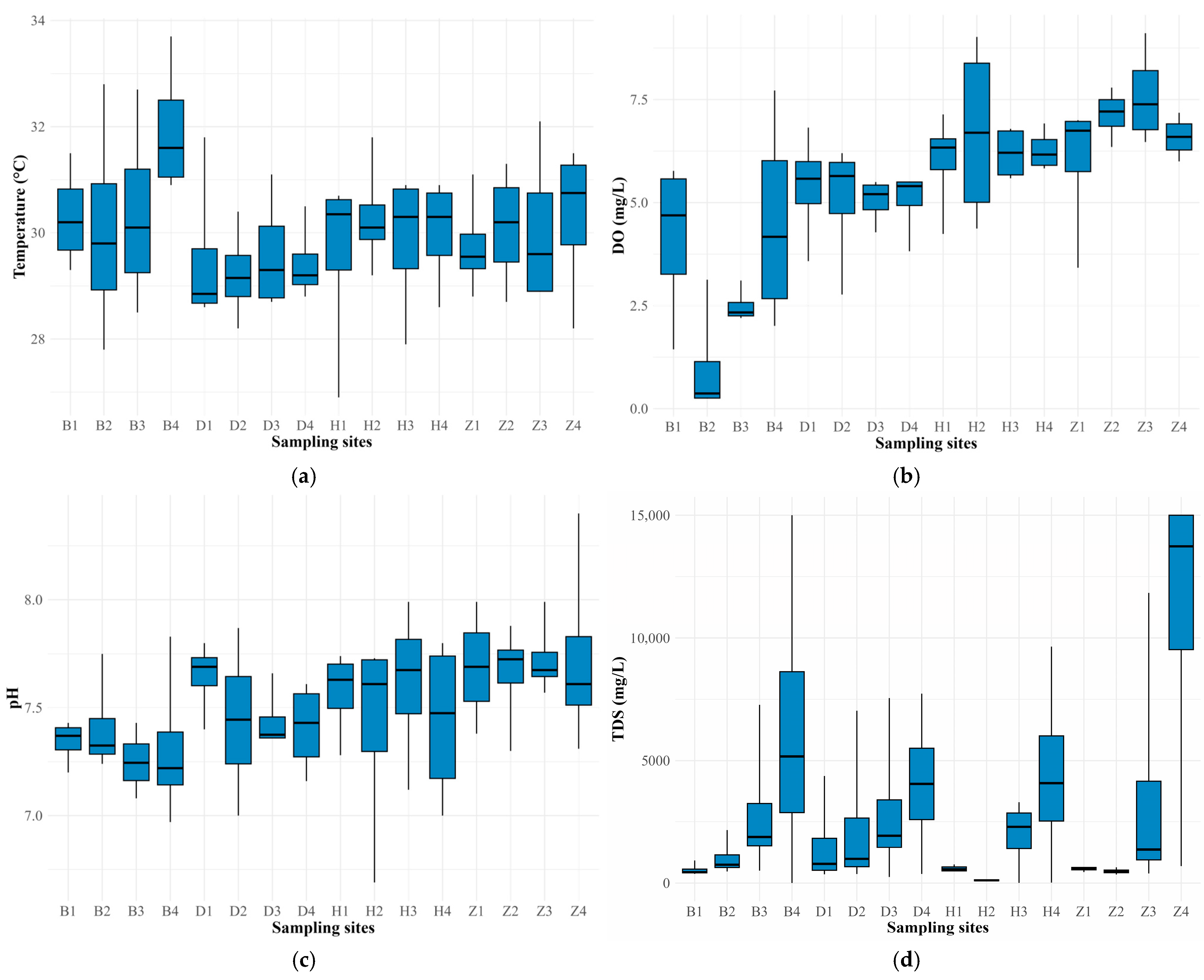

3.1. Physicochemical Variables

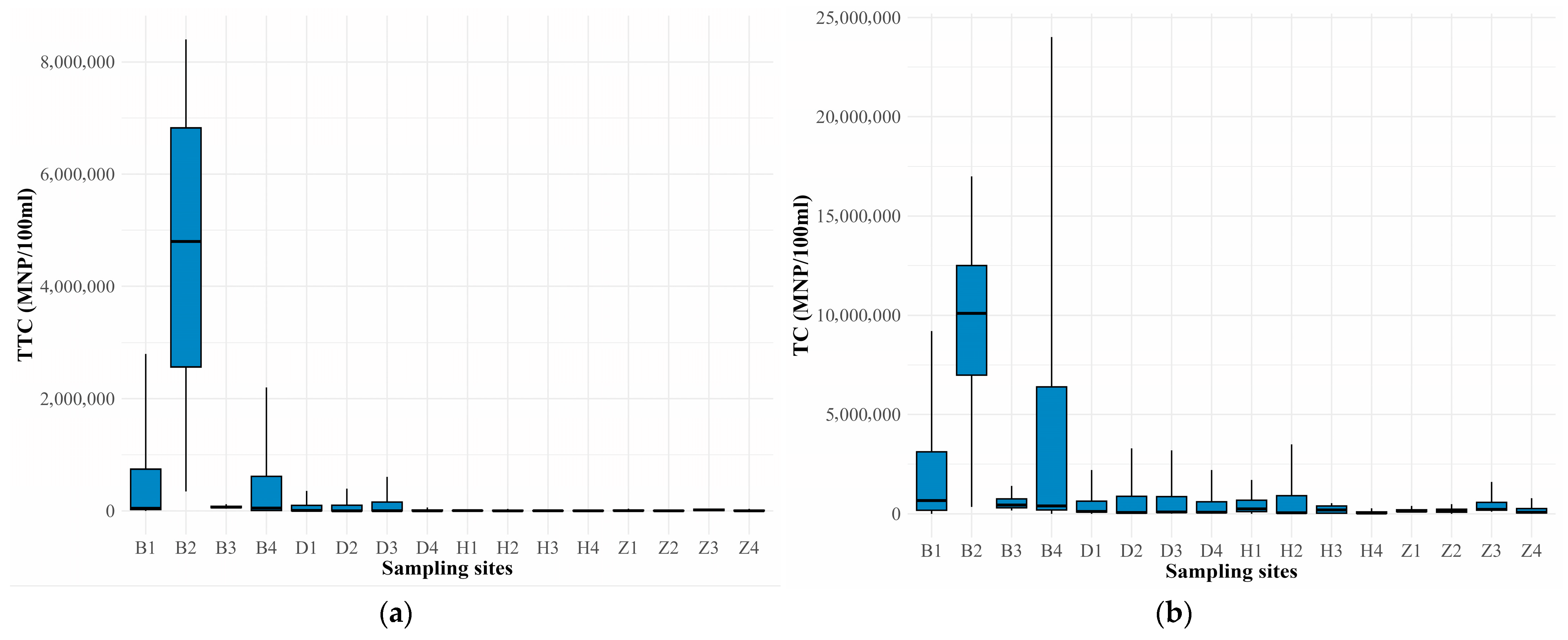

3.2. Microbiological Variables

3.3. Mann–Whitney U Test

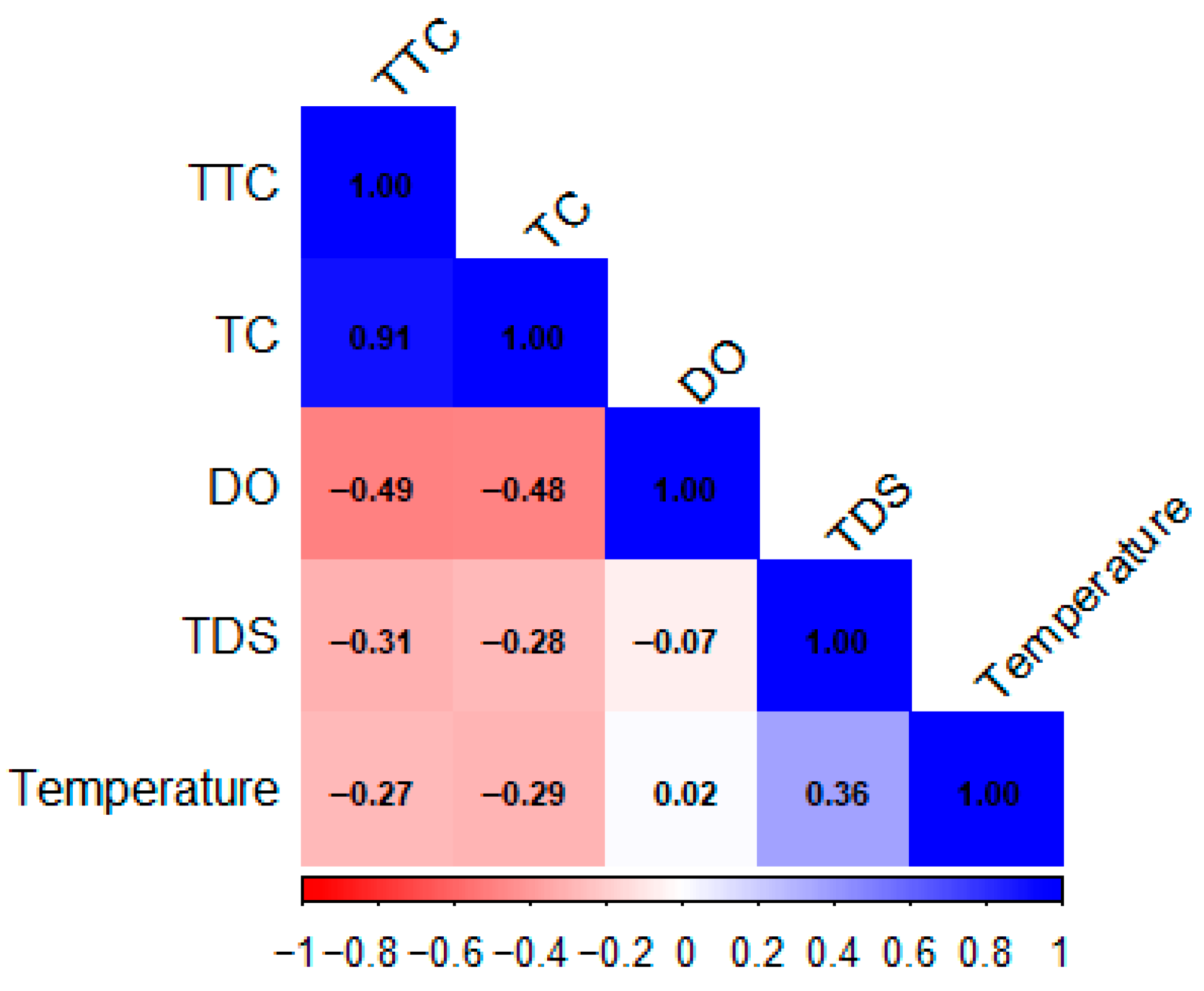

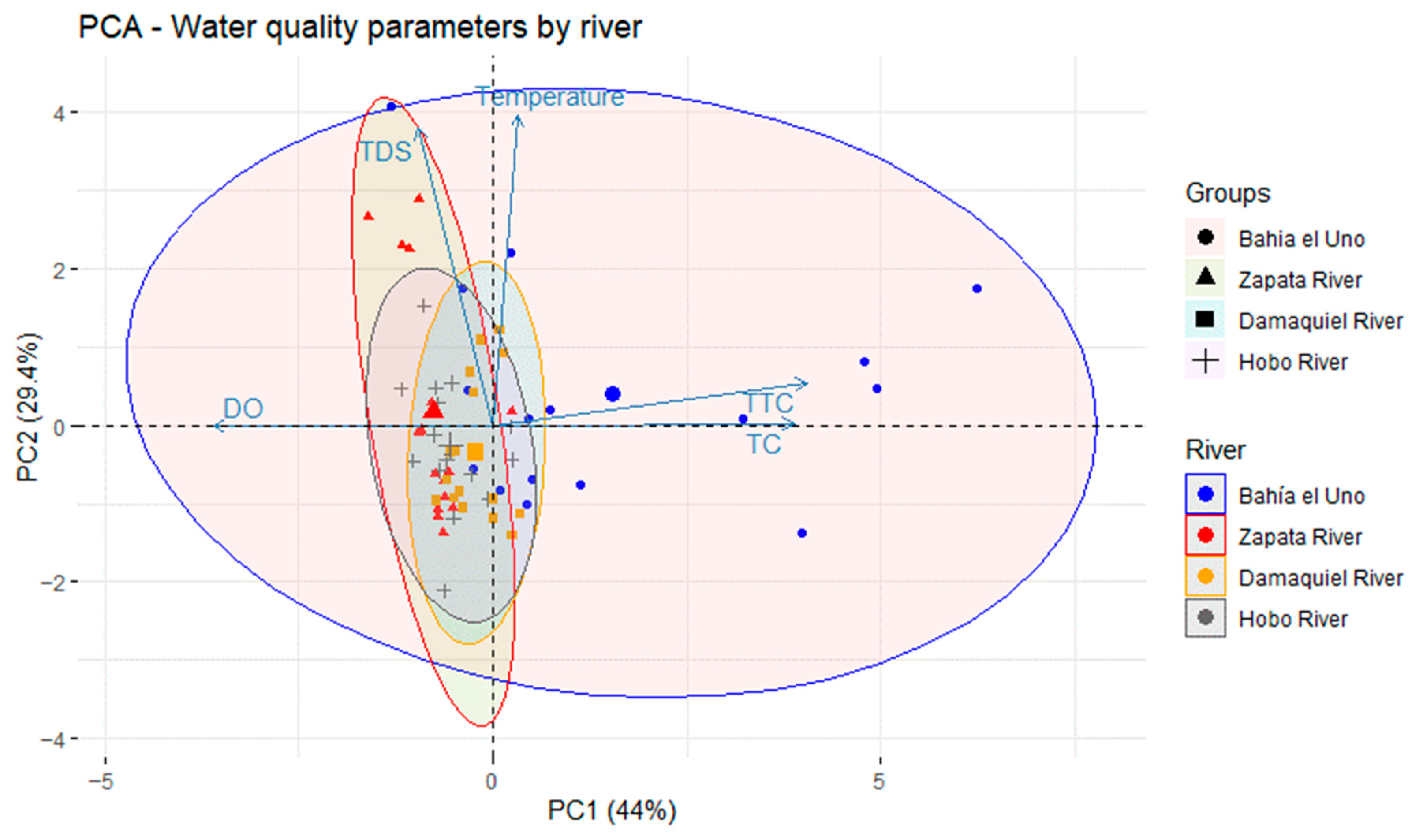

3.4. Spearman Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicochemical Parameters

4.2. Microorganisms—Coliforms

4.3. Eutrophication Conditions—Urbanization

4.4. Implications, Limitations, and Priorities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCs | Total coliforms |

| TTCs | Thermotolerant coliforms |

| °C | Centigrade degrees |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| GISMAC | Marine and coastal systems research group |

| IDEAM | Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies (Instituto de hidrología, meteorología y estudios ambientales de Colombia). |

| mL | Milliliter |

| mm/month | Millimeters per month |

| mg/L | Milligrams per liter |

| MPN | Most probable number |

| MPN/100 mL | Most probable number per 100 milliliters |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| TDSs | Total dissolved solids |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Unit | Dry Season 1 | Dry Season 2 | Wet Season 1 | Wet Season 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | ||

| TTCs (×104) | MPN/100 mL | 3.2 | 35 | 6.3 | 220 | 280 | 840 | 12 | 0.92 | 6.1 | 330 | 4 | 9.2 | 0.0078 | 630 | 7 | 0.049 |

| TCs (×104) | 24 | 35 | 35 | 2400 | 920 | 1100 | 140 | 54 | 110 | 1700 | 17 | 26 | 0.0078 | 920 | 54 | 0.079 | |

| DO | mg/L | 3.87 | 0.48 | 2.4 | 2.01 | 1.44 | 0.25 | 2.2 | 5.45 | 5.77 | 3.13 | 2.27 | 2.89 | 5.51 | 0.26 | 3.11 | 7.72 |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.24 | 7.19 | 7.24 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.08 | 6.97 | 7.34 | 7.35 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.43 | 7.75 | 7.43 | 7.83 | |

| TDSs | 370 | 694 | 1864 | 3840 | 460 | 814 | 1903 | 6500 | 440 | 480 | 513 | 3.73 | 922 | 2163 | 7280 | >15,000 | |

| T | °C | 29.3 | 29.3 | 28.5 | 30.9 | 30.6 | 32.8 | 30.7 | 32.1 | 29.8 | 27.8 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 31.5 | 30.3 | 32.7 | 33.7 |

| Parameter | Unit | Dry Season 1 | Dry Season 2 | Wet Season 1 | Wet Season 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z1 | Z2 | Z3 | Z4 | Z1 | Z2 | Z3 | Z4 | Z1 | Z2 | Z3 | Z4 | Z1 | Z2 | Z3 | Z4 | ||

| TTCs (×104) | MPN/100 mL | 0.22 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 0.21 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 4 | 2 | 0.78 | 3.7 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 2.7 | 0.079 |

| TCs (×104) | 9.2 | 11 | 24 | 9.2 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 6.3 | 40 | 49 | 160 | 79 | 12 | 0.13 | 21 | 0.11 | |

| DO | mg/L | 6.53 | 6.35 | 6.47 | 6.37 | 3.42 | 7.4 | 9.11 | 7.18 | 6.96 | 7.02 | 6.87 | 6.82 | 7.0 | 7.79 | 7.9 | 6.0 |

| pH | 7.99 | 7.88 | 7.99 | 8.4 | 7.58 | 7.3 | 7.67 | 7.58 | 7.38 | 7.73 | 7.57 | 7.64 | 7.8 | 7.72 | 7.68 | 7.31 | |

| TDSs | 455 | 457 | 1132 | 15,000 | 646 | 649 | 11830 | 12470 | 576 | 343 | 390 | 699 | 642 | 499 | 1599 | >15,000 | |

| T | °C | 29.5 | 29.7 | 28.9 | 30.3 | 31.1 | 31.3 | 32.1 | 31.2 | 28.8 | 28.7 | 28.9 | 28.2 | 29.6 | 30.7 | 30.3 | 31.5 |

| Parameter | Unit | Dry Season 1 | Dry Season 2 | Wet Season 1 | Wet Season 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | ||

| TTCs (×104) | NMP/100 mL | 0.68 | 0.078 | 0.6 | 0.37 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.036 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.022 |

| TCs (×104) | 35 | 5.4 | 35 | 28 | 0.017 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 15 | 350 | 54 | 4.0 | 0.13 | 0.011 | 0.049 | 0.17 | |

| DO | mg/L | 6.35 | 4.37 | 5.7 | 5.83 | 4.24 | 9.02 | 6.72 | 5.93 | 6.32 | 5.22 | 5.59 | 6.92 | 7.14 | 8.17 | 6.79 | 6.4 |

| pH | 7.28 | 6.69 | 7.12 | 7.23 | 7.57 | 7.5 | 7.76 | 7.8 | 7.69 | 7.72 | 7.99 | 7.0 | 7.74 | 7.73 | 7.59 | 7.72 | |

| TDSs | 508 | 79.7 | 2720 | 4800 | 766 | 125.8 | 3300 | 3360 | 631 | 153.6 | 8.17 | 19.85 | 487 | 98.8 | 1870 | 9650 | |

| T | °C | 26.9 | 29.2 | 27.9 | 28.6 | 30.7 | 31.8 | 30.8 | 30.9 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 29.8 | 29.9 | 30.6 | 30.1 | 30.9 | 30.7 |

| Parameter | Unit | Dry Season 1 | Dry Season 2 | Wet Season 1 | Wet Season 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | ||

| TTCs (×104) | NMP/100 mL | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.2 | 0.36 | 0.037 | 0.061 | 0.055 | 36 | 40 | 61 | 6.1 | 0.017 | 0.049 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| TCs (×104) | 12 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 12 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 220 | 330 | 320 | 220 | 0.079 | 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.35 | |

| DO | mg/L | 5.44 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 3.58 | 2.77 | 4.28 | 3.82 | 5.72 | 5.39 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 6.82 | 6.2 | 5.01 | 5.5 |

| pH | 7.71 | 7.57 | 7.66 | 7.55 | 7.4 | 7.32 | 7.39 | 7.31 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 7.36 | 7.16 | 7.67 | 7.87 | 7.36 | 7.61 | |

| TDSs | 987 | 777 | 1856 | 4760 | 4370 | 7040 | 7550 | 7730 | 352 | 364 | 246 | 366 | 587 | 1199 | 2010 | 3340 | |

| T | °C | 28.7 | 29 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 31.8 | 30.4 | 29.8 | 30.5 | 28.6 | 28.2 | 28.7 | 29.1 | 29 | 29.3 | 31.1 | 29.3 |

References

- Peters, N.E.; Meybeck, M.; Chapman, D.V. Effects of Human Activities on Water Quality. In Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences, 1st ed.; Anderson, M.G., McDonnell, J.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1409–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.L.; Grimm, N.B.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Fekete, B. Nitrogen and phosphorus fluxes from wátersheds of the northern U.S. from 1930 to 2000: Role of anthropogenic nutrient inputs, infrastructure, and runoff. Glob. Biochem. Cycles 2015, 29, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derfoufi, H.; Legssyer, M.; Belbachir, C.; Legssyer, B. Effect of physicochemical and microbiological parameters on the water quality of wadi Zegzel. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 13, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.; Jamil, N.R.; Abdullah, A.F.B. Impact of land uses on water quality in Malaysia: A review. Ecol. Process. 2019, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, R. The transport of material to the oceans: The river pathway. In Marine Geochemistry; Chester, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 14–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña, G. Characterization of some Golfo Dulce drainage basin rivers (Costa Rica). Rev. Biol. Trop. 1998, 46, 125–135. Available online: https://archivo.revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/view/29651 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Calvo, G.; Mora, J. Preliminary evaluation and classification of water quality in the Tárcoles and Reventazón river basins. Part IV: Statistical analysis of variables related to water quality. Tecnol. Marcha 2009, 22, 57–64. Available online: https://revistas.tec.ac.cr/index.php/tec_marcha/article/view/196/194 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- du Plessis, A. Persistent degradation: Global water quality challenges and required actions. One Earth 2022, 5, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobotaru, A. Influence of human activities on water quality of rivers and groundwaters from Brǎila Country. Ann. Univ. Oradea Geogr. Ser. 2015, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gianoli, A.; Hung, A.; Shiva, C. Relationship between total and thermotolerant coliforms with water physicochemical factors in six beaches of Sechura-Piura Bay 2016–2017. Salud Tecnol. Vet. 2018, 2, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covich, A.P.; Austen, M.C.; Bärlocher, F.; Chauvet, E.; Cardinale, B.J.; Biles, C.L.; Inchausti, P.; Dangles, O.; Solan, M.; Gessner, M.O.; et al. The role of biodiversity in the functioning of freshwater and marine benthic ecosystems. BioScience 2004, 54, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihinia, M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, N. Freshwater biodiversity at different habitats: Research hotspots with persistent and emerging themes. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Chakrabarty, M.; Rakshit, N.; Bhowmick, A.R.; Ray, S. Environmental factors as indicators of dissolved oxygen concentration and zooplankton abundance: Deep learning versus traditional regression approach. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 100, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, D.A.; Chendake, A.D.; Ghosal, D.; Mathuriya, A.S.; Kumar, S.S.; Pandit, S. Advanced microbial fuel cell for biosensor applications to detect quality parameters of pollutants. In Bioremedation, Nutrient, and Other Valuable Produc Recovery; Singh, L., Madhab Mahapatra, D.M., Thakur, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.H.R.; Dutra, M.L.S.; Lima, N.S.; Silva, G.M.; Miranda, R.C.M.; Firmo, W.C.A.; Moura, A.R.L.; Monteiro, A.S.; Silva, L.C.N.; Silva, D.F.; et al. Study of the Influence of Physicochemical Parameters on the Water Quality Index (WQI) in the Maranhão Amazon. Brazil. Water 2022, 14, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Zapata, G.; Herrera, L.; Cantera, J.; Galvis, A.; Cardona, D.; Hurtado, I. Methodology to Determine Eutrophication Levels in Aquatic Ecosystems. Rev. Asoc. Colomb. Cienc. Biológicas 2012, 24, 112–128. Available online: https://www.revistaaccb.org/r/index.php/accb/article/view/81/81 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Aristizabal-Tique, V.H.; Gomez-Gallego, D.D.; Ramos-Hernandez, I.T.; Arcos-Arango, Y.; Polanco-Echeverry, D.N.; Velez-Hoyos, F.J. Assessing the Physicochemical and Microbiological Condition of Surface Waters in Urabá-Colombia: Impact of Human Activities and Agro-Industry. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Zuñiga, A.; Peña-Mejía, C.; Bastidas-Salamanca, M.; Ricaurte-Villota, C. Region 8: Sinú-Urabá. In Oceanographic Regionalisation: A Dynamic Vision of the Caribbean, 1st ed.; INVEMAR Special Publications Series#14; Ricaurte-Villota, C., Bastidas-Salamanca, M., Eds.; Marine and Coastal Research Institute José Benito Vives De Andréis (INVEMAR): Santa Marta, Colombia, 2017; pp. 140–155. Available online: https://www.invemar.org.co/en/publicaciones (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Toro-Valencia, V.G.; Mosquera, W.; Barrientos, N.; Bedoya, Y. Ocean circulation of the Gulf of Urabá using high temporal resolution wind fields. Bol. Cient. CIOH 2019, 38, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, P.; Gómez., E.; Toro., F. Mean circulation pattern in Colombia Bay in the two extreme climatic epochs. In Proceedings of the XXIII Latin American Hydraulics Congress, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2–6 September 2008. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/8096/Roldan.Toro.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Campillo, A.; Taupin, J.D.; Betancur, T.; Patris, N.; Vergnaud, V.; Paredes, V.; Villegas, P. A multi-tracer approach for understanding the functioning of heterogeneous phreatic coastal aquifers in humid tropical zones. Hydrolog. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 600–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association-APHA; American Water Works Association-AWWA; Water Environmental Federation-WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Masindi, T.K.; Gyedu-Ababio, T.; Mpenyana-Monyatsi, L. Pollution of Sand River by Wastewater Treatment Works in the Bushbuckridge Local Municipality, South Africa. Pollutants 2022, 2, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies—Ideam; Marine and Coastal Research Institute “Jose Benito Vives de Andreis”—Invemar. Water Monitoring and Tracking Protocol; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; 631p. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment, Housing and Territorial Development; Ministry of Social Protection. Resolution Number (2115), 22 June 2007. Through Which the Characteristics, Basic Instruments and Frequencies of the Water Quality Control and Monitoring System for Human Consumption Are Identified, 2007; 37p. Available online: https://minvivienda.gov.co/normativa/resolucion-2115-2007 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Decree 1594 of 26 June 1984. In Partially Regulating Title I of Law 9 of 1979, as well as Chapter II of Title VI—Part III—Book II and Title III of Part III—Book I—of Decree-Law 2811 of 1974 Regarding the Use of Water and Liquid Waste; Ministry of Health: Bogotá, Colombia, 1984. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=18617 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development Sector. Decree 703 of 20 April 2018. By Which Some Adjustments Are Made to Decree 1076 of 2015, by Means of Which the Single Regulatory Decree of the Environment and Sustainable Development Sector Is Issued, and Other Provisions are Dictated, Bogotá, Colombia. 2018. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=85980 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Decree 1076 of 26 May 2015. Issuing the Single Regulatory Decree for the Environment and Sustainable Development Sector, Bogotá, Colombia. 2015. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=78153 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ríos-Tobón, S.; Agudelo-Cadavid, R.M.; Gutiérrez-Builes, L.A. Pathogens and microbiological indicators of water quality for human consumption. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Publica 2017, 35, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, N.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Scherman, P.A. Critical Analysis of Environmental Water Quality in South Africa: Historic and Current Trends Report to the Water Research Commission; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bienfang, P.K.; Defelice, S.V.; Laws, E.A.; Brand, L.E.; Bidigare, R.R.; Christensen, S.; Trapido-Rosenthal, H.; Hemscheidt, T.K.; McGillicuddy, D.J.; Anderson, D.M.; et al. Prominent human health impacts from several marine microbes: History, ecology, and public health implications. Int. J. Microbiol. 2010, 2011, 152815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caissie, D. The thermal regime of rivers: A review. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 1389–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.C.; Mcgregor, G.R.; Petts, G.E. River energy budgets with special reference to river bed processes. Hydrol. Process. 1998, 12, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.F.; Albertson, L.K.; Algar, A.C.; Dugdale, S.J.; Edwards, P.; England, J.; Gibbins, C.; Kazama, S.; Komori, D.; MacColl, A.D.C.; et al. Rising water temperature in rivers: Ecological impacts and future resilience. WIREs Water 2024, 11, e1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.W.; Hannah, D.M.; Moore, R.D.; Brown, L.E.; Nobilis, F. Recent advances in stream and river temperature research. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.W.; Clack, P.D.; Walling, D.E. Water-air temperature relationships in a Devon River system and the role of flow. Hydrol. Process. 2003, 17, 3069–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, O.; Stefan, H.G. Stream temperature/air temperature relationship: A physical interpretation. J. Hydrol. 1999, 218, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Murrell, J.A.; Rojas-Badía, M.M.; Romeu-Álvarez, B.; Rojas-Hernández, N.M.; Heydrich-Pérez, M. Indicator bacteria of fecal contamination in water quality assessment: A literature review. Rev. CENIC Cienc. Biol. 2013, 44, 24–34. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=181229302004 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- World Metrological Organization—WMO. Update Predicts 60% Chance of La Niña. Press Release. 11 September 2024. Available online: https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-update-predicts-60-chance-of-la-nina (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ruiz, J.F.; Melo, J.Y. Short, Medium, and Long-Term Climate Prediction Report in Colombia; Time and Climate Modeling Group, Meteorology Subdirectorate—IDEAM: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Trujillo, J.; Ramos De La Hoz, I.; Garavito Mahecha, J.D. Monthly Meteomarine Bulletin of the Colombian Caribbean No. 131/November 2023 Cartagena de Indias D.T. and C.; Colombia General Maritime Directorate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2023; Available online: https://mindefensa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991299828707231&context=L&vid=57MDN_INST:CECOLDO&lang=es&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ortiz Trujillo, J.; Llorente Valderrama, A.J. Monthly Meteomarine Bulletin of the Colombian Caribbean No.133/January 2024 Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C.; Colombia General Maritime Directorate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024; Available online: https://mindefensa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991299827207231&context=L&vid=57MDN_INST:CECOLDO&lang=es&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Llorente Valderrama, A.J.; Ramos De La Hoz, I.; Garavito Mahecha, J.D. Monthly Meteomarine Bulletin of the Colombian Caribbean No.136/Abril 2024 Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C.; Colombia General Maritime Directorate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024; Available online: https://mindefensa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991312108607231&context=L&vid=57MDN_INST:CECOLDO&lang=es&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ortiz Trujillo, J.A.; Ramos De La Hoz, I.; Garavito Mahecha, J.D. Monthly Meteomarine Bulletin of the Colombian Caribbean No.140/Agosto 2024 Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C.; Colombia General Maritime Directorate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024; Available online: https://mindefensa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991318571907231&context=L&vid=57MDN_INST:CECOLDO&lang=es&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Dirección General Marítima—Dimar; Centro de Investigaciones Oceanográficas e Hidrográficas del Caribe—CIOH; Servicio Hidrográfico Nacional—SHN. Derrotero de las Costas y Áreas Insulares del Caribe Colombiano; Dimar: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, G.C.; Berman, C.H. An Ecological Perspective on In-Stream Temperature: Natural Heat Dynamics and Mechanisms of Human-Caused Thermal Degradation. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castillo, A.C.; Rodríguez, A. Physicochemical index of water quality for the management of tropical flooded lagoons. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2008, 56, 1905–1918. Available online: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-77442008000400026&lng=en (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Shrestha, A.K.; Basnet, N.B. The correlation and regression analysis of physicochemical parameters of river water for the evaluation of percentage contribution to electrical conductivity. J. Chem. 2018, 9, 8369613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, M.; Daffonchio, D.; Booth, J.; Giomi, F. Dissolved Oxygen in Heterogeneous Environments Dictates the Metabolic Rate and Thermal Sensitivity of Tropical Aquatic Crab. Fron. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 767471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz., H.; Orozco., S.; Vera., A.; Suárez., J.; García., E.; Mercedes., N.; Jiménez, J. Relationship between dissolved oxygen, rainfall and temperature: Zahuapan river, Tlaxcala, Mexico. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2015, 6, 59–74. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-24222015000500005&lng=es&tlng= (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Roslev., P.; Bjergbaek. L., A.; Hesselsoe, M. Effect of oxygen on survival of faecal pollution indicators in drinking water. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldreich, E.E. Microbiological Quality of Source Waters for Water Supply. In Drinking Water Microbiology; McFeters, G.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjumea Hoyos, C.A.; Álvarez Montes, G. Oxygen demand by sediments in different stretches of the Negro Rionegro River. Antioquia. Colombia. Producción Limpia 2017, 12, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Martínez, S.; Solano Pardo, G.A. Evaluation of the Impact of Domestic Wastewater Discharges. Through the Application of the Contamination Index (ICOMO) in Caño Grande. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Environmental Engineering, Santo Tomas University, Villavicencio, Colombia, 2018. Available online: https://repository.usta.edu.co/items/06ab0e76-a7b9-4b29-8765-33efdfe4cd10 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Olds, H.T.; Corsi, S.R.; Dila, D.K.; Halmo, K.M.; Bootsma, M.J.; McLellan, S.L. High levels of sewage contamination released from urban areas after storm events: A quantitative survey with sewage specific bacterial indicators. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onifade, O.; Lawal, Z.K.; Shamsuddin, N.; Abas, P.E.; Lai, D.T.C.; Gӧdeke, S.H. Impact of Seasonal Variation and Population Growth on Coliform Bacteria Concentrations in the Brunei River: A Temporal Analysis with Future Projection. Water 2025, 17, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitter, C.; Petzoldt, H.; Korth, A.; Schwab, F.; Stange, C.; Hambsch, B.; Tiehm, A.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Gescher, J.; Hügler, M. Seasonal dynamics in the number and composition of coliform bacteria in drinking water reservoirs. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Hamilton, K.; Toze, S.; Cook, S.; Page, D. A review on microbial contaminants in stormwater runoff and outfalls: Potential health risks and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodus, B.; O’Malley, K.; Dieter, G.; Gunawardana, C.; McDonald, W. Review of emerging contaminants in green stormwater infrastructure: Antibiotic resistance genes, microplastics, tire wear particles, PFAS, and temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornevi, A.; Bergstedt, O.; Forsberg, B. Precipitation effects on microbial pollution in a river: Lag structures and seasonal effect modification. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckerfield, S.J.; Quilliam, R.S.; Waldron, S.; Naylor, L.A.; Li, S.; Oliver, D.M. Rainfall-driven E. coli transfer to the stream-conduit network observed through increasing spatial scales in mixed land-use paddy farming karst terrain. Water Res. X 2019, 5, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Public Health Surveillance Protocol. In Morbidity Due to Acute Diarrhoeal Disease; National Institute of Health: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024. Available online: https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Lineamientos/Pro_EDA%202024.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ahumada-Santos, Y.P.; Báez-Flores, M.E.; Díaz-Camacho, S.P.; Uribe-Beltrán, M.J.; López-Angulo, G.; Vega-Aviña, R.; Chávez-Duran, F.A.; Montes-Avila, J.; Carranza-Díaz, O.; Möder, M.; et al. Distribución espaciotemporal de la contaminación bacteriana del agua residual agrícola y doméstica descargada a un canal de drenaje (Sinaloa, México). Cienc. Mar. 2014, 40, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.A. Review on Research and Studies on Dissolved Oxygen and Its Affecting Parameters. Int. J. Res. 2016, 3, 18–22. Available online: https://www.ijrrjournal.com/IJRR_Vol.3_Issue.8_Aug2016/IJRR004.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Kitsiou, D.; Karydis, M. Coastal marine eutrophication assessment: A review on data analysis. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 778–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yu, J.; Lei, G.; Xue, B.; Zhang, F.; Yao, S. Indirect influence of eutrophication on air—water exchange fluxes, sinking fluxes, and occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Water Res. 2017, 122, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennish, M.J. Eutrophication of Estuarine and Coastal Marine Environments: An Emerging Climatic-Driven Paradigm Shift. Open J. Ecol. 2025, 15, 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Cai, W.J.; Carstensen, J.; Conley, D.J.; Fry, B.; Hu, X.; Quiñones-Rivera, Z.; Rosenberg, R.; Slomp, C.P.; Turner, R.E.; et al. Eutrophication-driven deoxygenation in the coastal ocean. Oceanography 2014, 27, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos Pulido, M.P.; Ávila de Navia, S.L.; Estupiñán Torres, S.M.; Gómez Prieto, A.C. Microbiological indicators of contamination of the water sources. Nova 2005, 3, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Gutiérrez, J.V. Determination of oxidation rates, nitrification and sedimentation in the process of self-purification of a mountain river. Ingeniare. Rev. Chil. Ing. 2016, 24, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauta-Calle, G.; Velazco, M.; Gutiérrez, D.; Vázquez, G.; Rivera, S.; Morales, O.; Abril, A. Water quality assessment of rivers in the city of Cuenca in Ecuador. Maskana 2019, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, N.; Briones, N.; Quiroz, S.; Peña, D.; Ortiz, Y. Characterization and Analysis of Water Quality in Urban Environments through the implementation of an Embedded System with IoT Technology. Rev. Tecnol. ESPOL—RTE 2024, 36, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Vásquez, M.; Velandia, G. Evaluation of the Microbiological Quality of Water for Human Consumption in the Villages of El Alto del Águila and El Tunal in the Municipality of Zipaquirá, Cundinamarca. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca, Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.universidadmayor.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unicolmayor/5719/Documento%20Proyecto%20de%20Grado.pdf?sequence=14&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 July 2025).

| Water Body | Site Location | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahia el Uno | B1 | Before the entrance to Bahia el Uno | 8°06′46″–76°43′22″ |

| B2 | New canal—before the entrance to Bahía el Uno | 8°06′8.276″–76°43′38.5″ | |

| B3 | Caño el Uno * | 8°06′31″–76°44′11″ | |

| B4 | River mouth | 8°06′18″–76°44′20″ | |

| Zapata River | Z1 | Upstream, away from the entrance to Zapata | 8°40′328″–76°37′59″ |

| Z2 | Before entering to Zapata | 8°40′36″–76°38′42″ | |

| Z3 | Zapata * | 8°40′33″–76°38′02″ | |

| Z4 | River mouth | 8°44′10.0″–76°38′15″ | |

| Hobo River | H1 | Upstream before the entrance to Hobo River | 8°49′09.7″–76°26′30.9″ |

| H2 | Pond | 8°59′48.6″–76°26′17.8″ | |

| H3 | Hobo river * | 8°50′44.3″–76°26′27.7″ | |

| H4 | River mouth | 8°50′45.9″–76°26′27.3″ | |

| Damaquiel River | D1 | Last stream flowing into the river—before Damaquiel | 8°44′10.0″–76°36′23.3″ |

| D2 | Entrance to the river | 8°44′08.2″–76°36′24″ | |

| D3 | Damaquiel * | 8°44′22.5″–76°36′18.1″ | |

| D4 | River mouth | 8°44′30.8″–76°36′14.3″ | |

| Sampling/Month | Season | T (°C) | DO (mg/L) | pH | TDS (mg/L) | TTC (MPN/100 mL) | TC (MPN/100 mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—November | Dry (DS1) | 26.9–30.9 | 0.48–6.53 | 6.6–8.4 | 79.7–15,000 | 780–22 × 105 | 54,000–24 × 106 |

| 2—January | Dry (DS2) | 29.8–32.8 | 0.25–9.11 | 6.97–7.8 | 125.8–12,470 | 360–84 × 105 | 35,000–11 × 106 |

| 3—April | Wet (WS1) | 27.8–31.1 | 2.27–7.02 | 7.00–7.99 | 3.73–699 | 4000–33 × 105 | 40,000–17 × 106 |

| 4—August | Wet (WS2) | 29.0–33.7 | 0.26–8.17 | 7.31–7.87 | 98.8–>15,000 ▪ | 20–63 × 105 | 78–9.2 × 106 |

| Range | 26.9–33.7 | 0.25–9.11 | 6.69–8.4 | 19.85–>15,000 | 20–84 × 105 | 78–24 × 106 | |

| Mean ± SD | 30.0 ± 1.3 | 5.32 ± 2.05 | 7.51 ± 0.30 | 2777 ± 3964 | 399,812 ± 1,405,339 | 1,542,043 ± 4,097,424 | |

| n | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| Reference | -–- | 4.0 + | 4.5–9.0 * | -–- | ˂200 ** | 1000 ** | |

| TTC (MPN/100 mL) | TC (MPN/100 mL) | OD (mg/L) | TDS (mg/L) | T (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahia el Uno | Mann–Whitney U | 24.000 | 21.000 | 16.000 | 31.000 | 28.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.401 | 0.247 | 0.093 | 0.916 | 0.674 | |

| Zapata River | Mann–Whitney U | 22.000 | 20.000 | 24.000 | 22.500 | 17.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.293 | 0.207 | 0.401 | 0.318 | 0.115 | |

| Hobo River | Mann–Whitney U | 26.000 | 20.000 | 21.000 | 20.000 | 29.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.528 | 0.207 | 0.248 | 0.208 | 0.752 | |

| Damaquiel River | Mann–Whitney U | 22.000 | 32.000 | 19.000 | 8.000 | 23.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.293 | 1.000 | 0.171 | 0.012 | 0.343 |

| Spearman’s Rho | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTC (MPN/100 mL) | TC (MPN/100 mL) | DO (mg/L) | TDS (mg/L) | T (°C) | pH | ||

| TTC (MPN/100 mL) | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.906 | −0.495 | −0.307 | −0.270 | −0.355 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.031 | 0.004 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| TC (MPN/100 mL) | Correlation coefficient | 0.906 | 1.000 | −0.484 | −0.277 | −0.294 | −0.319 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.010 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DO (mg/L) | Correlation coefficient | −0.495 | −0.484 | 1.000 | −0.066 | 0.017 | 0.495 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.607 | 0.892 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| TDS (mg/L) | Correlation coefficient | −0.307 | −0.277 | −0.066 | 1.000 | 0.365 | 0.048 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.607 | 0.003 | 0.709 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| T (°C) | Correlation coefficient | −0.270 | −0.294 | 0.017 | 0.365 | 1.000 | 0.039 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.031 | 0.018 | 0.892 | 0.003 | 0.758 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| pH | Correlation coefficient | −0.355 | −0.319 | 0.495 | 0.048 | 0.39 | 1.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.709 | 0.758 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Páez-Gómez, S.T.; Zambrano-Ortiz, M.M.; Toro-Valencia, V.G. Relationship Between Microbiological and Physicochemical Parameters in Water Bodies in Urabá, Colombia. Processes 2026, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010035

Páez-Gómez ST, Zambrano-Ortiz MM, Toro-Valencia VG. Relationship Between Microbiological and Physicochemical Parameters in Water Bodies in Urabá, Colombia. Processes. 2026; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010035

Chicago/Turabian StylePáez-Gómez, Sirley Tatiana, Mónica María Zambrano-Ortiz, and Vladimir Giovanni Toro-Valencia. 2026. "Relationship Between Microbiological and Physicochemical Parameters in Water Bodies in Urabá, Colombia" Processes 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010035

APA StylePáez-Gómez, S. T., Zambrano-Ortiz, M. M., & Toro-Valencia, V. G. (2026). Relationship Between Microbiological and Physicochemical Parameters in Water Bodies in Urabá, Colombia. Processes, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010035