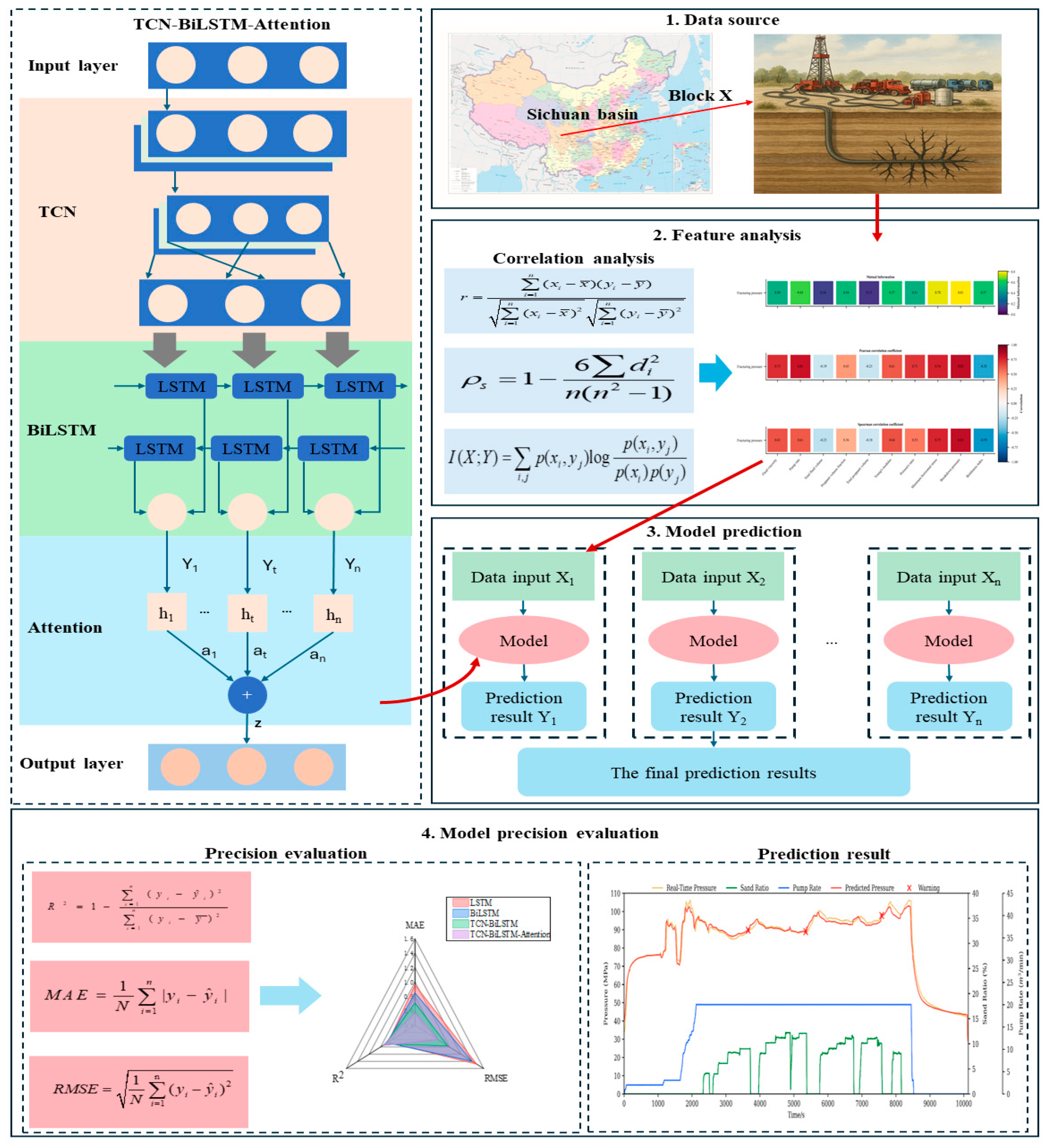

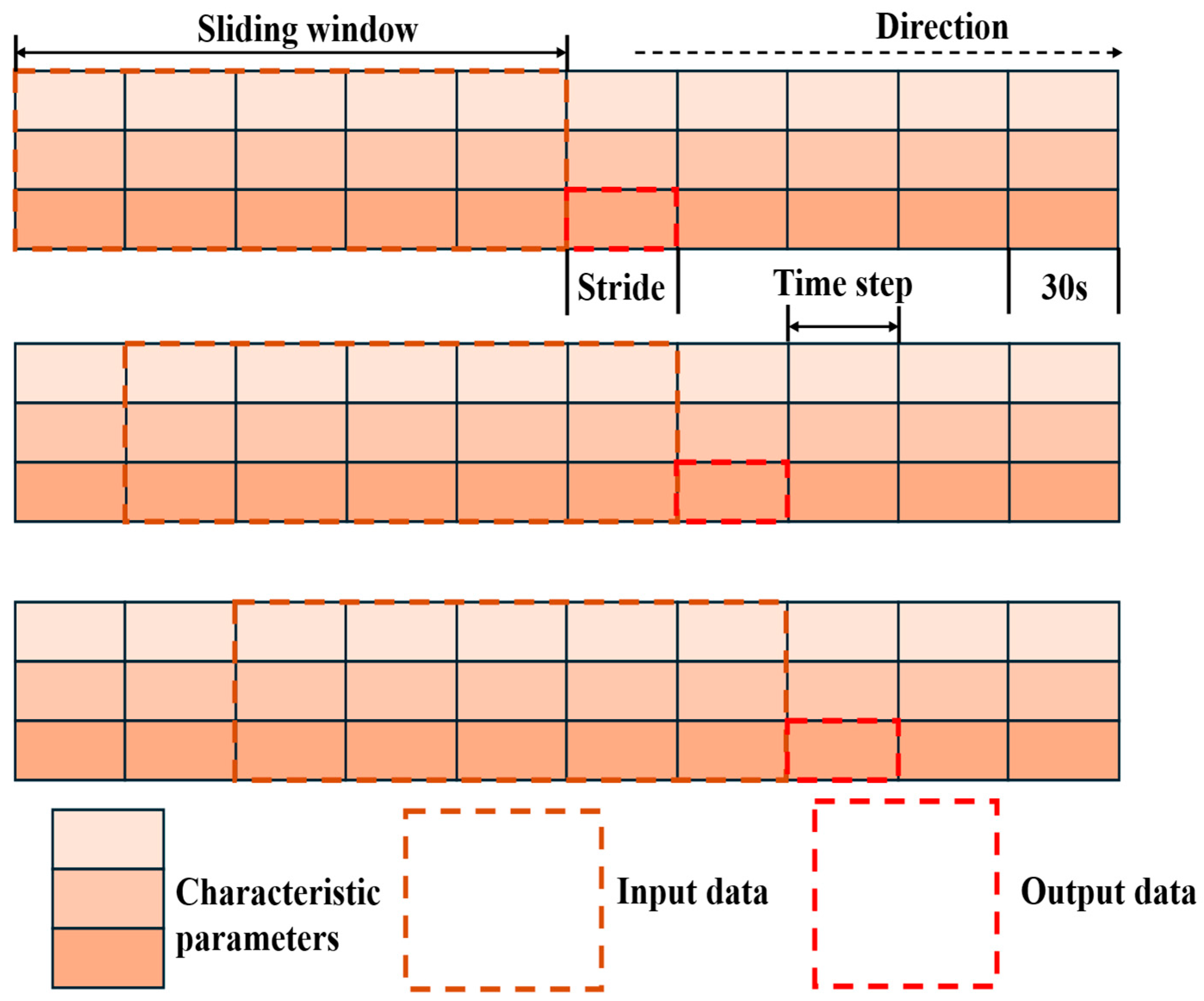

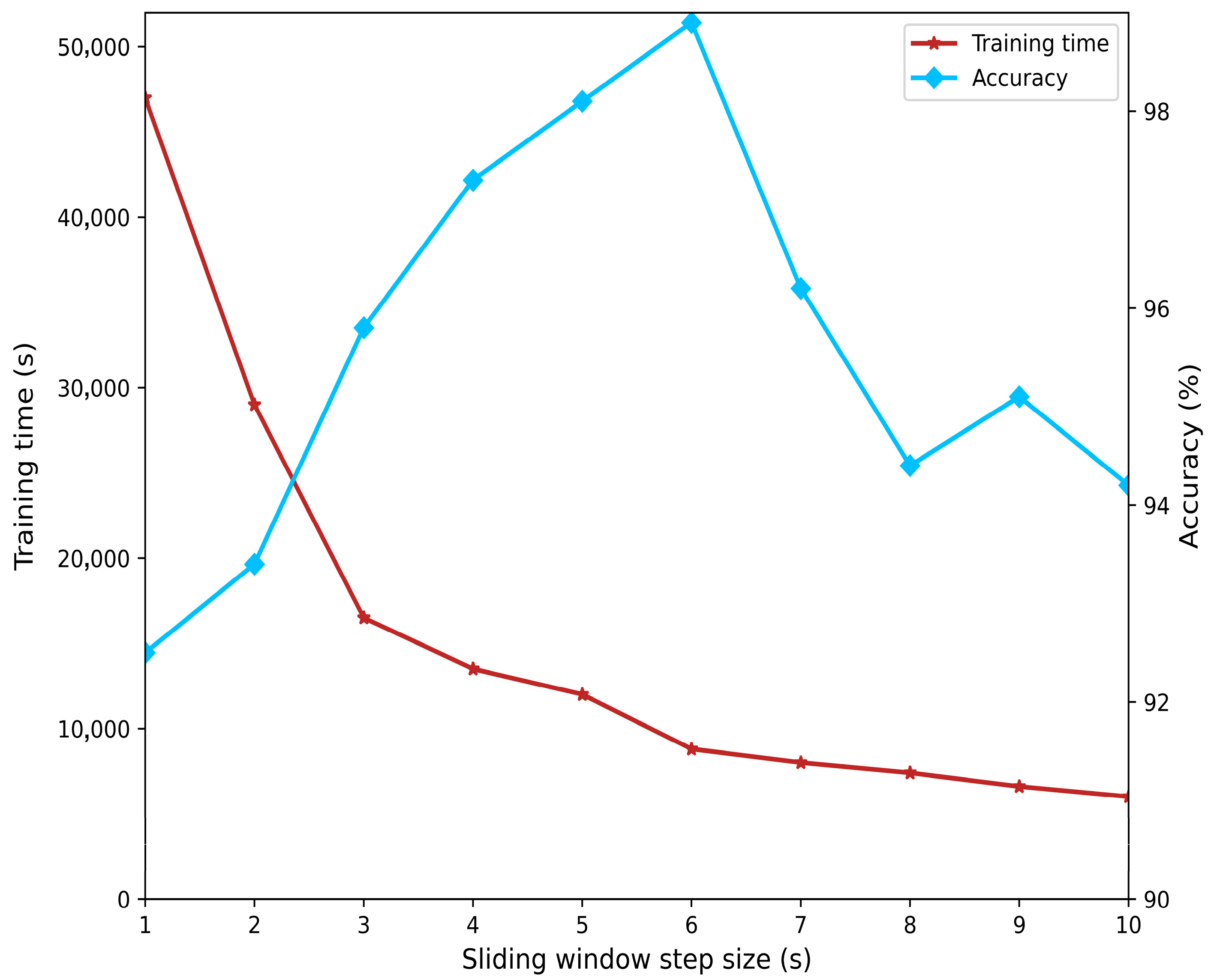

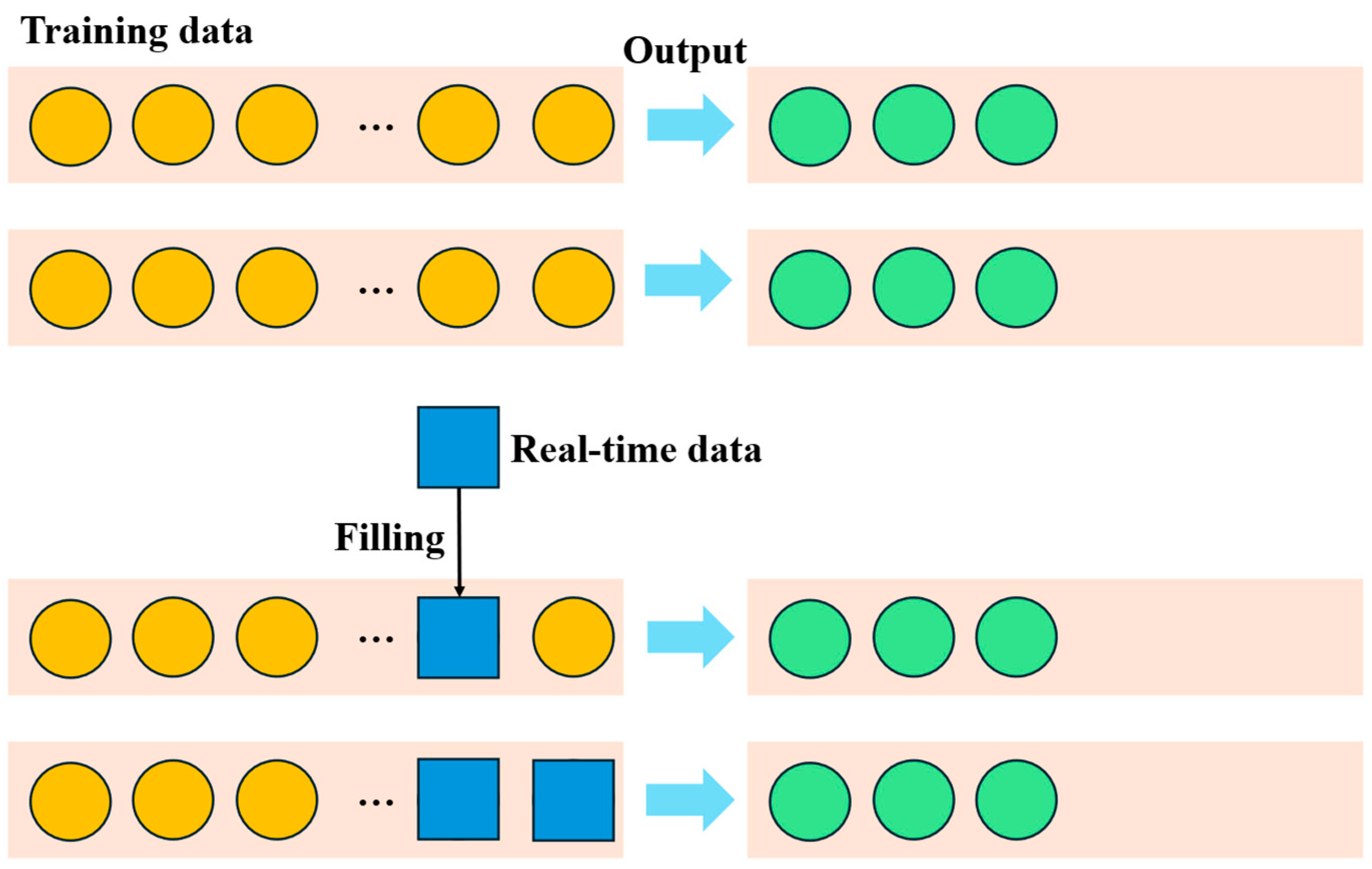

3.1. Feature Analysis

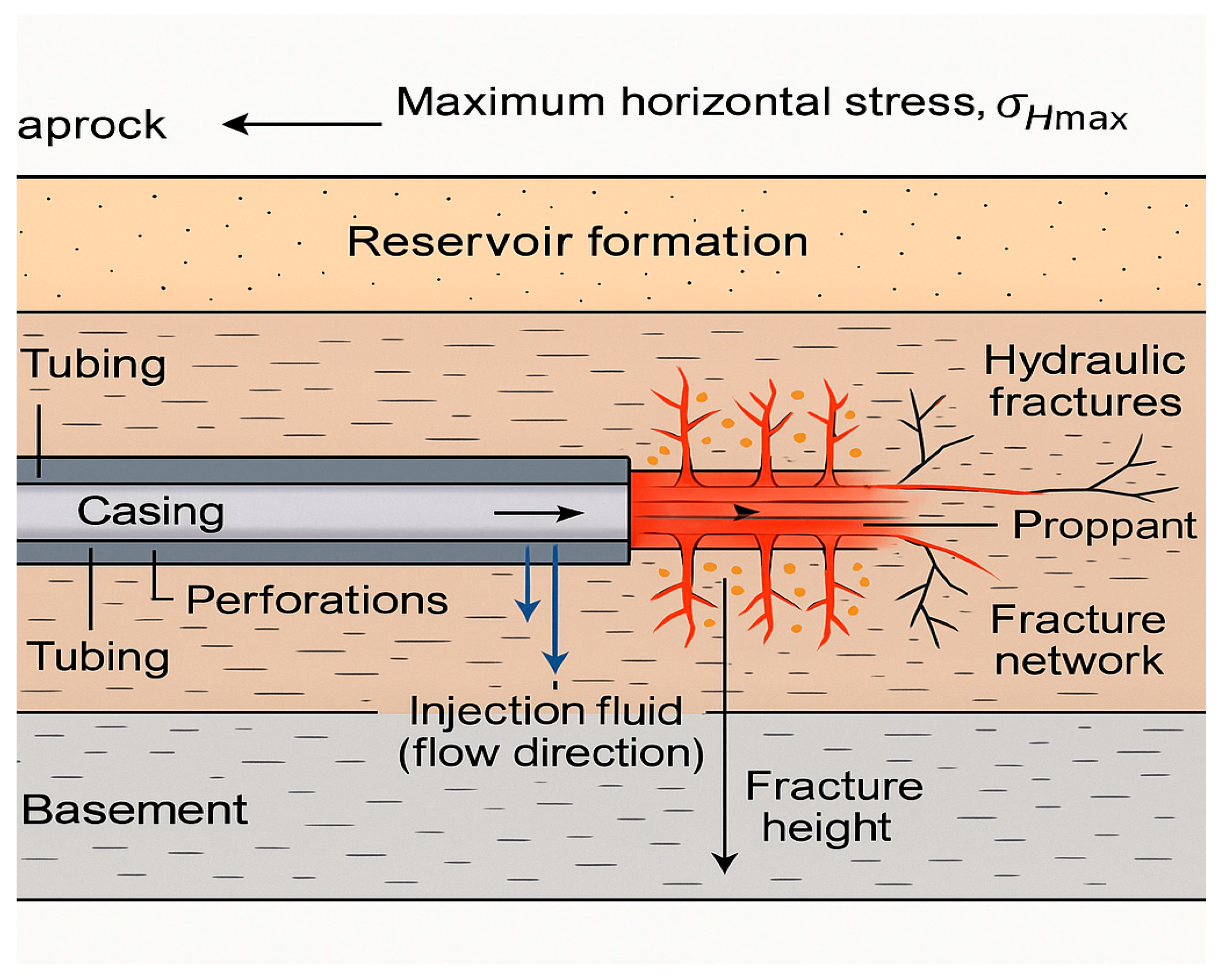

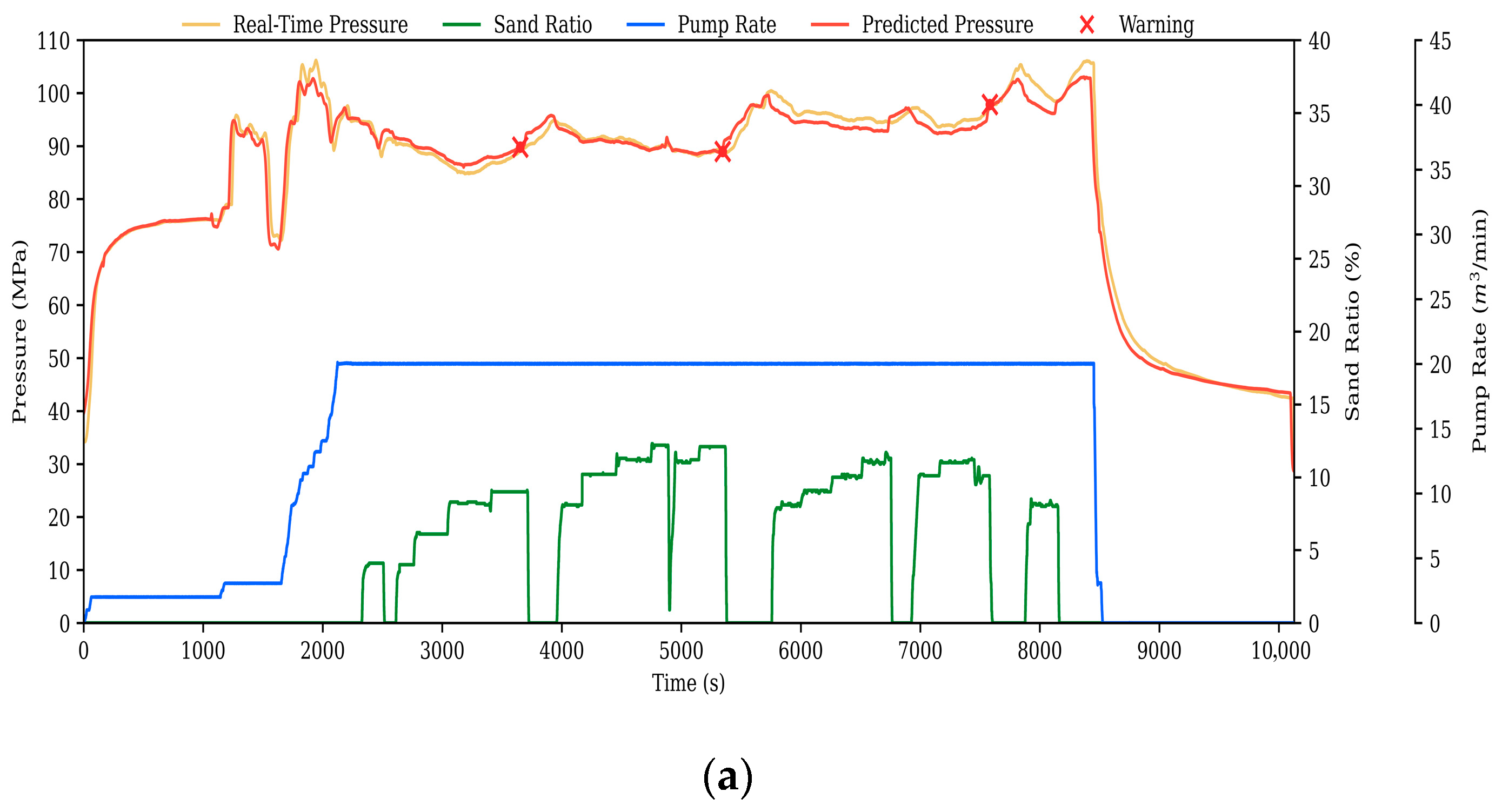

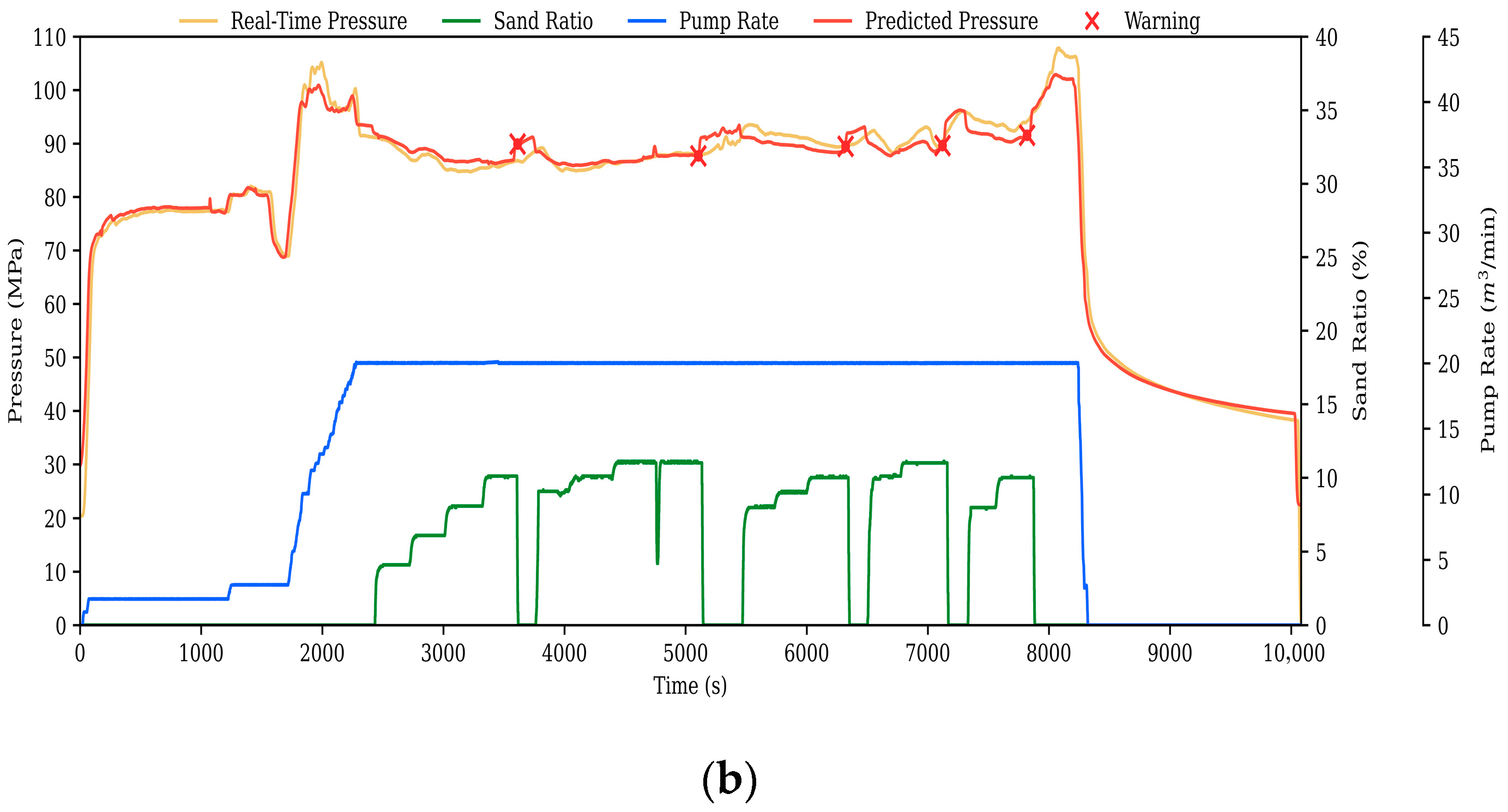

The dataset in this paper originates from the X shale gas block in China’s Sichuan Basin. This resource-rich block has produced a cumulative total of 95 billion cubic meters of natural gas as of September 2025, with proven geological reserves exceeding 1 trillion cubic meters. The study compiled historical hydraulic fracturing operation data for this block, with operational conditions shown in

Figure 7.

Based on this, the paper utilizes natural language processing (NLP) technology to extract fracturing operation parameter design documents, obtaining the required detailed data as shown in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, these data can be summarized as fracturing engineering parameters, primarily divided into two categories: controllable dynamic parameters such as pump rate, proppant volume fraction, and fluid viscosity; and uncontrollable static data such as Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and minimum horizontal stress.

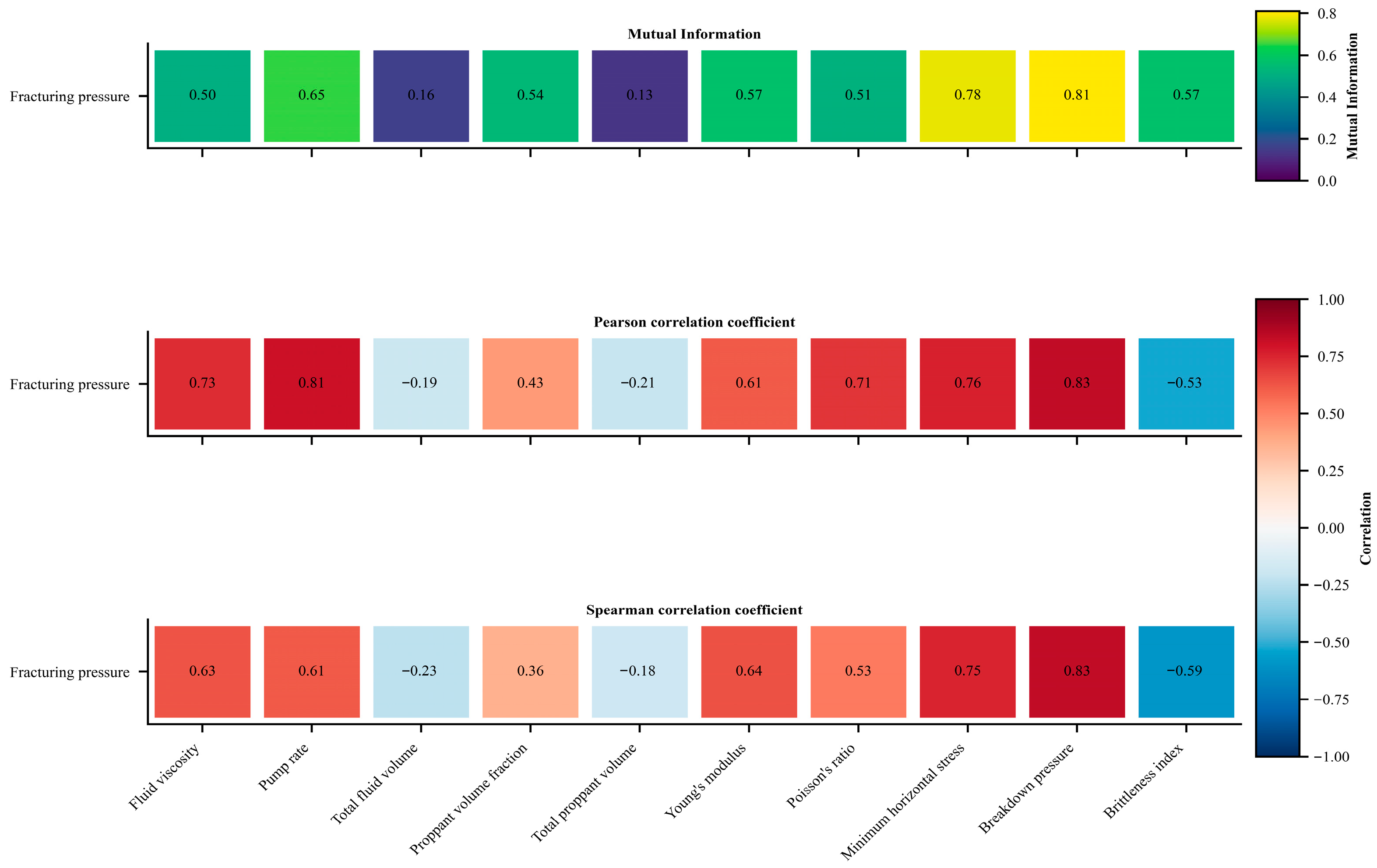

The correlation between target parameters and input parameters is one of the key factors affecting model performance [

33,

34]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Spearman’s analysis are suitable for describing linear relationships between two continuous variables [

35,

36], making them applicable for selecting data features of fracturing parameters in this study. The Pearson calculation formula is shown in Equation (10), while the Spearman formula is shown in Equation (11).

where

is the Pearson correlation coefficient, with a value range of [−1, 1];

is the sample size;

and

are the

i-th observed values of the two variables, respectively;

and

are the sample means of the two variables, respectively.

where

denotes the Spearman coefficient, which ranges from −1 to 1.

represents the rank difference between the fracturing pressure and target parameters.

indicates the rank of sample

in

X, while

denotes the rank of sample

in

Y.

signifies the sum of squared rank differences across all samples; a smaller value indicates greater consistency in the order of the two variables and stronger correlation.

represents the normalization factor.

Correlation analysis can only reveal linear relationships between fracturing pressure and other parameters. However, variations in fracturing pressure are not solely governed by linear relationships; they also involve nonlinear relationships, which are equally significant. Mutual information analysis, a commonly used method for examining nonlinear relationships [

37], employs the calculation formula shown in Equation (13).

where

denotes the nonlinear relationship between the random engineering parameter

X and the objective parameter fracturing pressure, and

represents the joint probability distribution, i.e., the probability that

and

occur simultaneously. is the ratio of the probability that

and

occur together to the probability that they occur independently.

Based on the correlation analysis results in

Figure 8, it can be observed that among the input parameters, FV, PR, YM, PRO, MHS, BP, and BI exhibit strong correlations with fracturing pressure. Meanwhile, PVF exhibits moderate correlations in both Pearson and Spearman analyses, but a stronger correlation in mutual information analysis. Some of the literature studies also treat PVF as an input parameter [

38] since it can cause sand blockage in fractures, leading to fracturing pressure surges. Therefore, PVF is also included as an input feature. TPV and TFV exhibit weak correlations with fracturing pressure across all three correlation analyses and are thus excluded as input parameters.

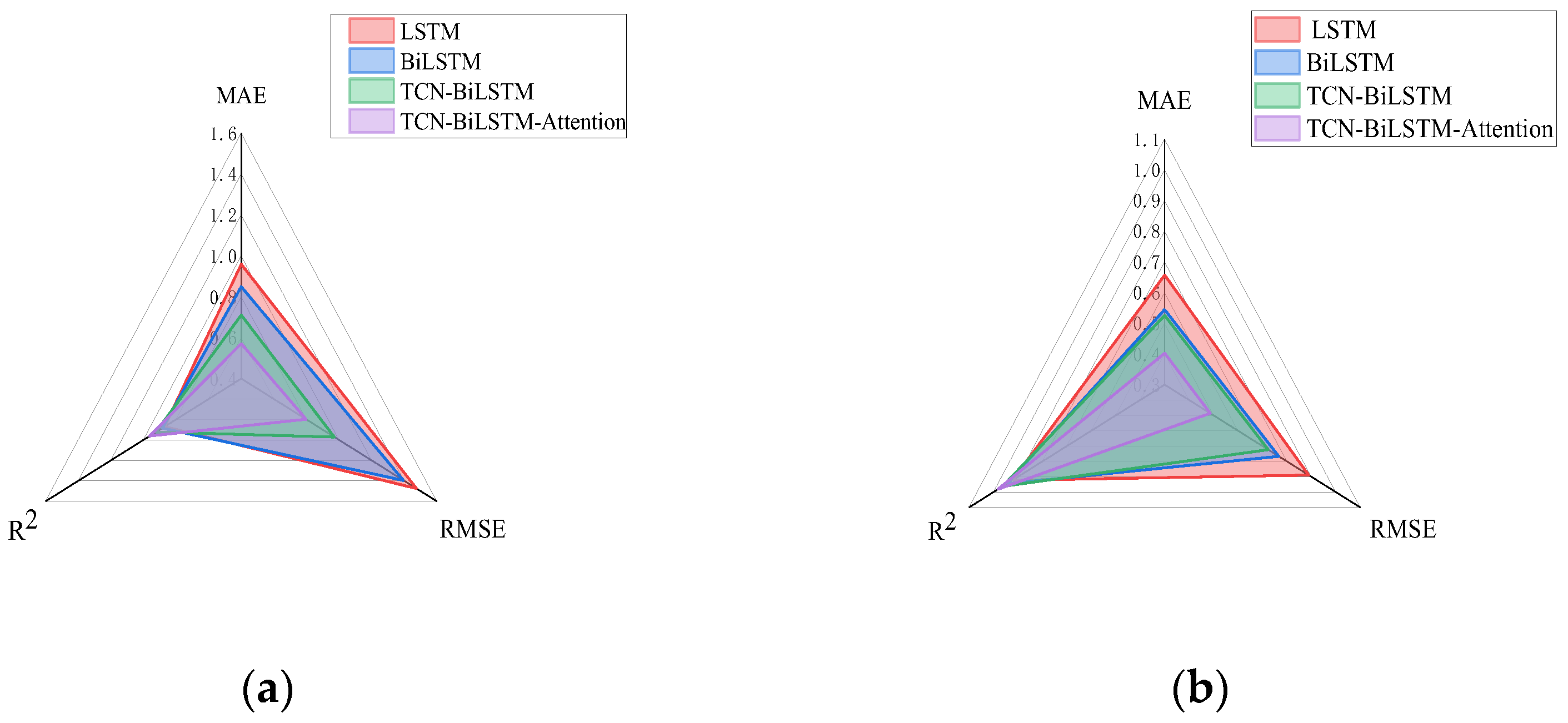

This paper first performs preliminary screening based on Pearson, Spearman, and mutual information metrics to eliminate features exhibiting high multicollinearity and weak correlations. To further validate the actual contribution of each input feature to predictive performance, feature ablation experiments are conducted on the model using evaluation metrics. Common evaluation metrics such as MAE, R

2, and RMSE effectively reflect variations in pressure predictions [

39]. Therefore, these three metrics are adopted as evaluation indicators for fracturing pressure prediction, with their calculation formulas as shown in the Equations (14)–(16).

where

represents the actual fracturing pressure value,

represents the model-predicted fracturing pressure value, and

denotes the size of the dataset. The smaller the values of

MAE and

RMSE, the higher the prediction accuracy of the model; these values cannot be negative. The closer R

2 is to 1, the higher the variance in the data explained by the model and the better the prediction performance. The data range is [0, 1].

This study conducted ablation experiments by sequentially removing individual features while retaining the full-feature model as a baseline, then retraining the model to compare changes in MAE, RMSE, and R

2 on the test set. As shown in

Table 2, omitting PVF and FV significantly reduces model accuracy, whereas removing TFV and TPV has a minor impact on performance. The model evaluating all input features yielded overall performance metrics of MAE = 0.5423 MPa, RMSE = 0.8159 MPa, and R

2 = 0.9576. After removing TFV, the model’s MAE increased by 0.028 MPa, the RMSE rose by 0.0246 MPa, and the R

2 decreased by 0.0051. This suggests that removing TFV has a negligible impact on the model, resulting in minimal changes in evaluation metrics. After removing TPV, the model’s MAE increased by 0.1409 MPa, RMSE rose by 0.1053 MPa, and R

2 decreased by 0.0147. Therefore, TFV and TPV exhibit low predictive contribution and are redundant features that can be removed from the model to simplify its structure and enhance computational efficiency. This indicates that core construction parameters contribute more substantially to fracture pressure prediction, while auxiliary variables primarily serve a corrective role. TFV and TPV are redundant parameters. Therefore, the input features for this study comprise eight variables: FV, PR, PVF, YM, PRO, MHS, BP, and BI. The feature selection results are shown in

Table 3.

Normalization effectively enhances prediction accuracy, improves model stability, and ensures regularization effects [

40]. Due to differing units among feature parameters in the dataset, hidden influence relationships may be overlooked during model analysis. To accelerate model convergence and enhance stability and accuracy [

41], considering that the data in this paper is distributed within an interval range, we employ maximum–minimum normalization to map fracturing operation data to the [0, 1] interval. The calculation formula is shown in the Equation (17).

where

represents the raw feature data, and

represents the normalized feature values.

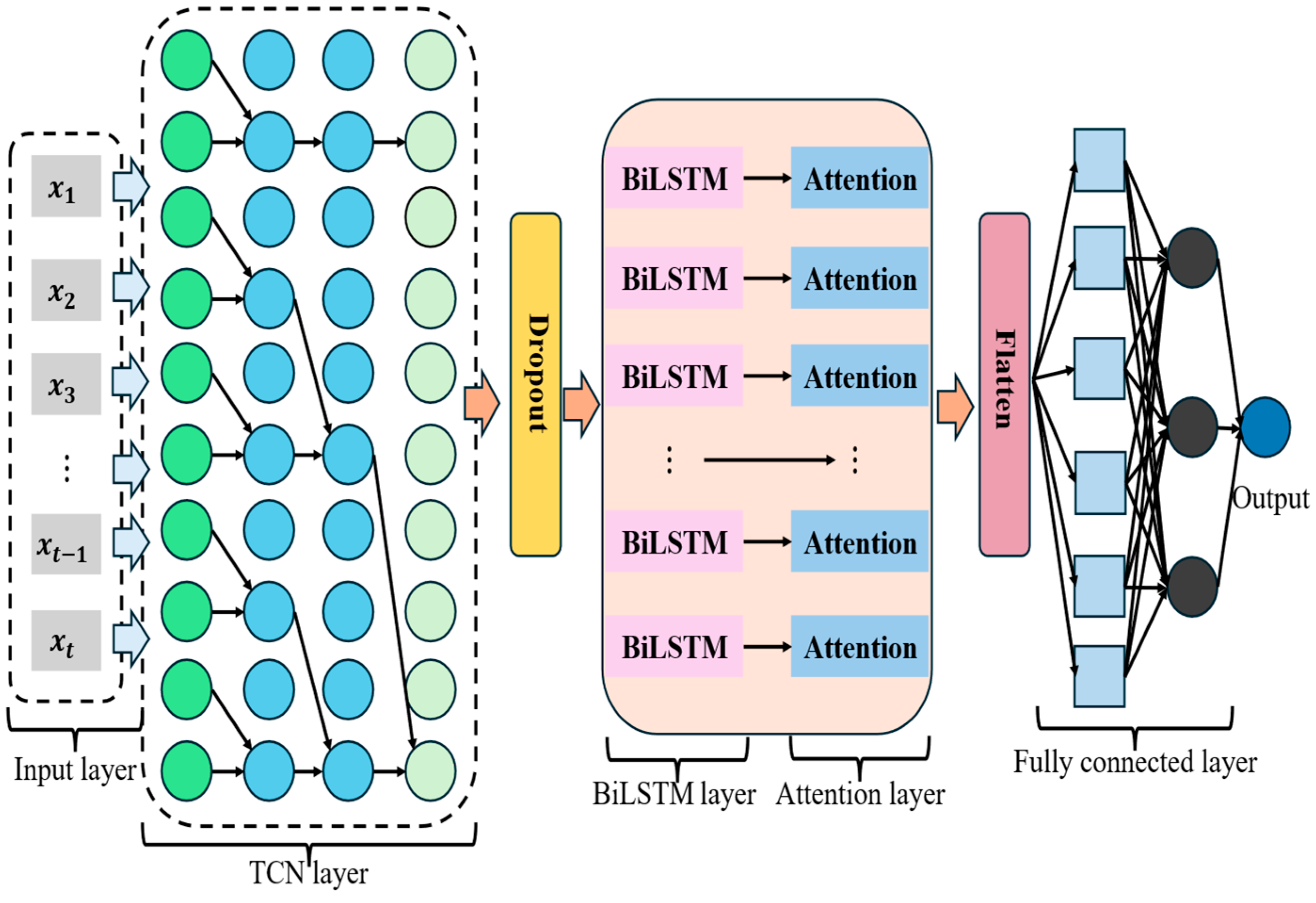

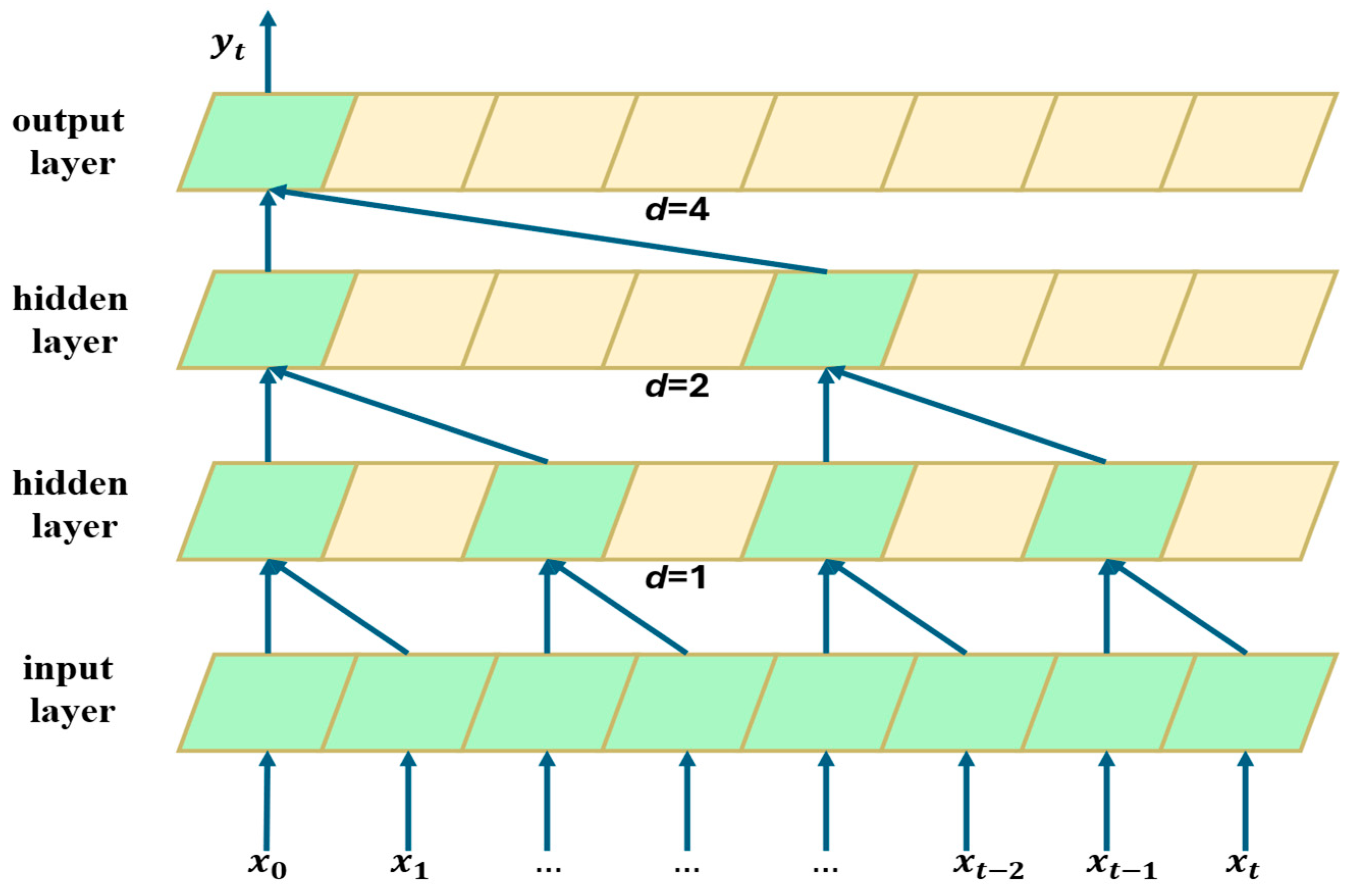

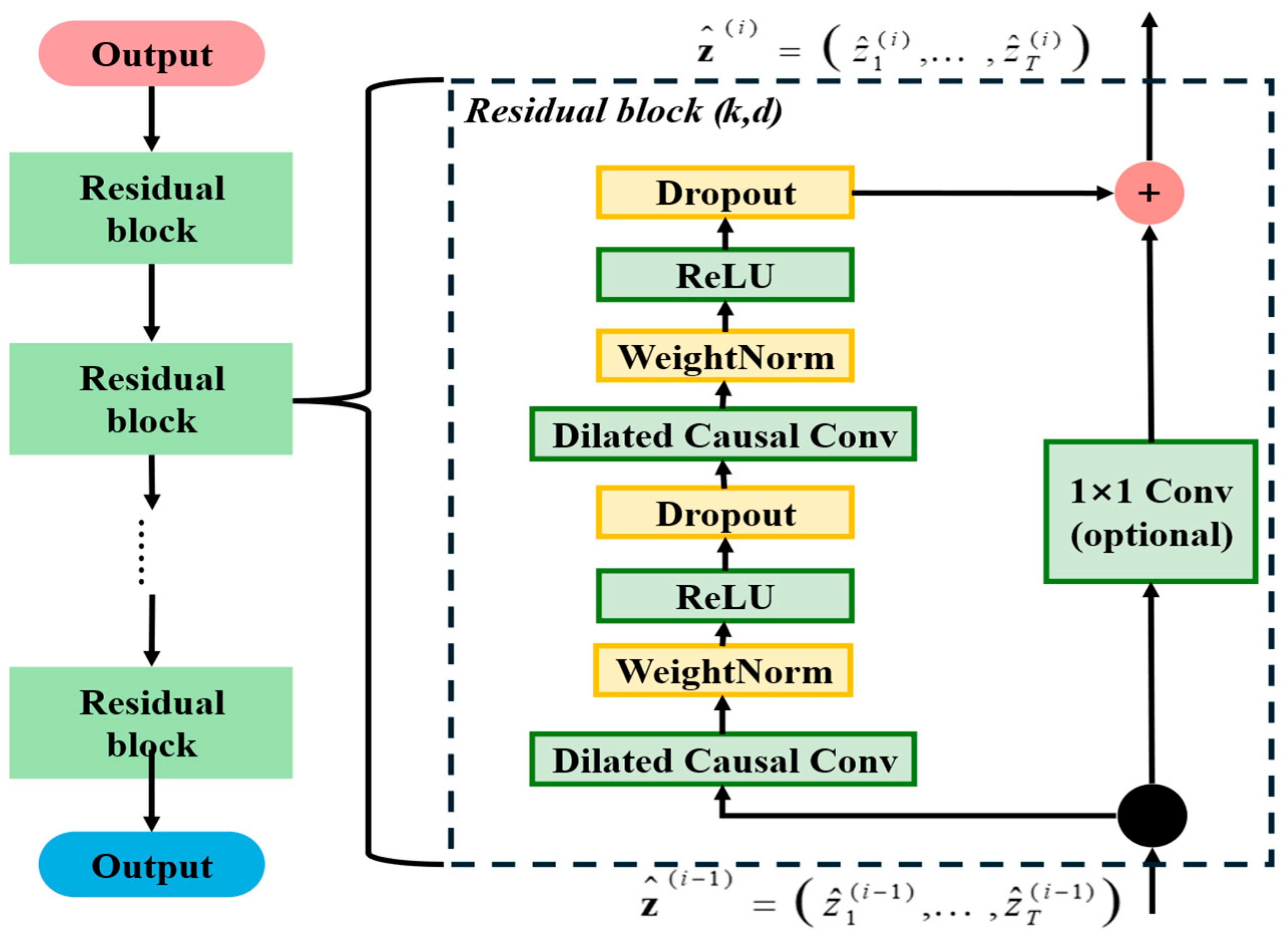

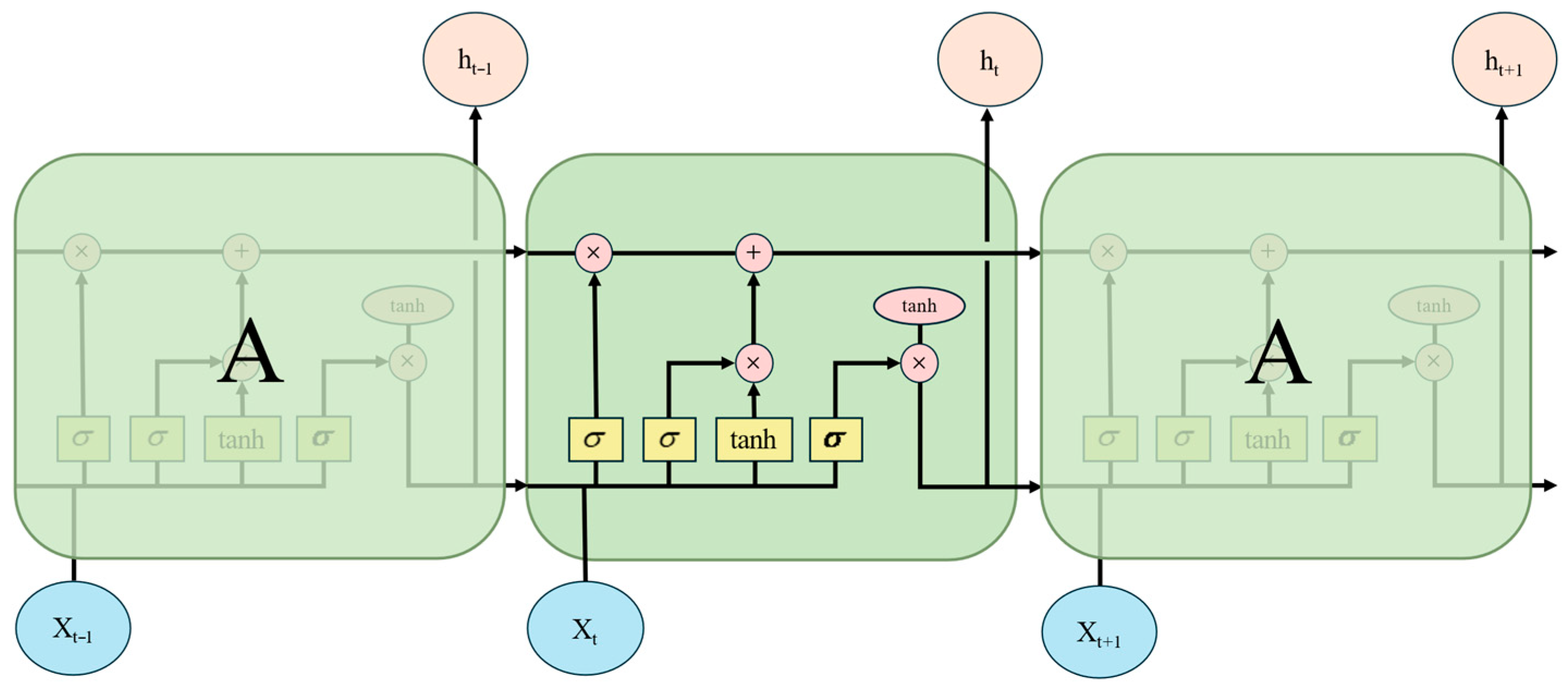

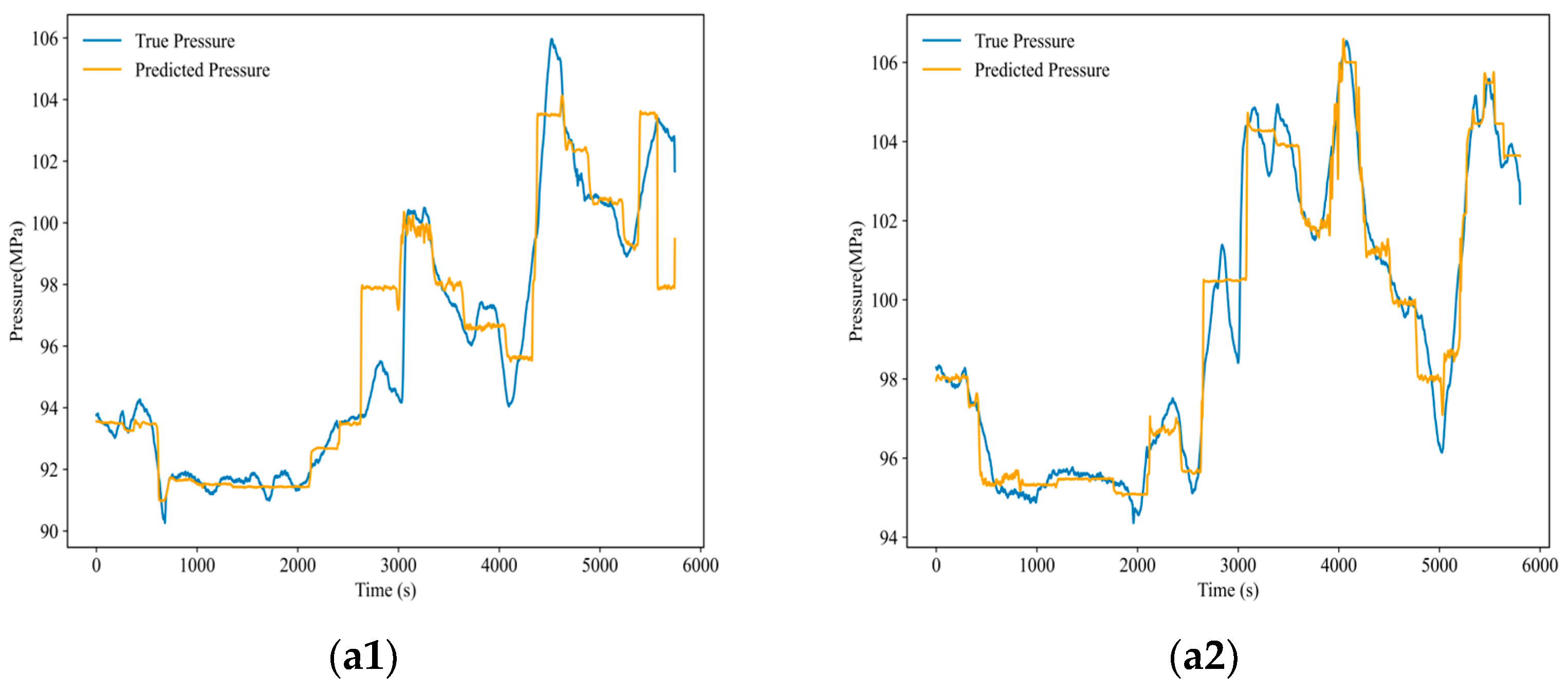

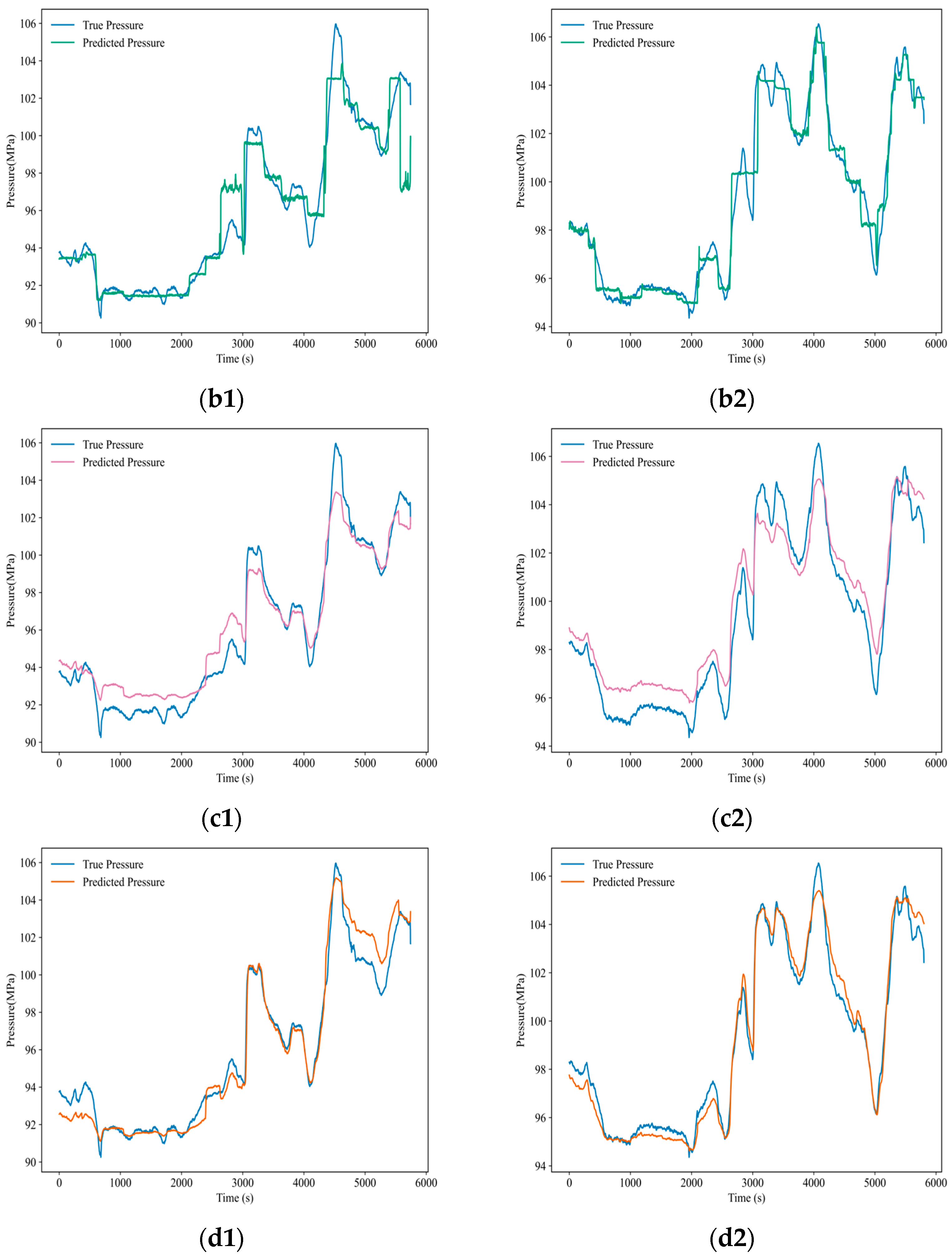

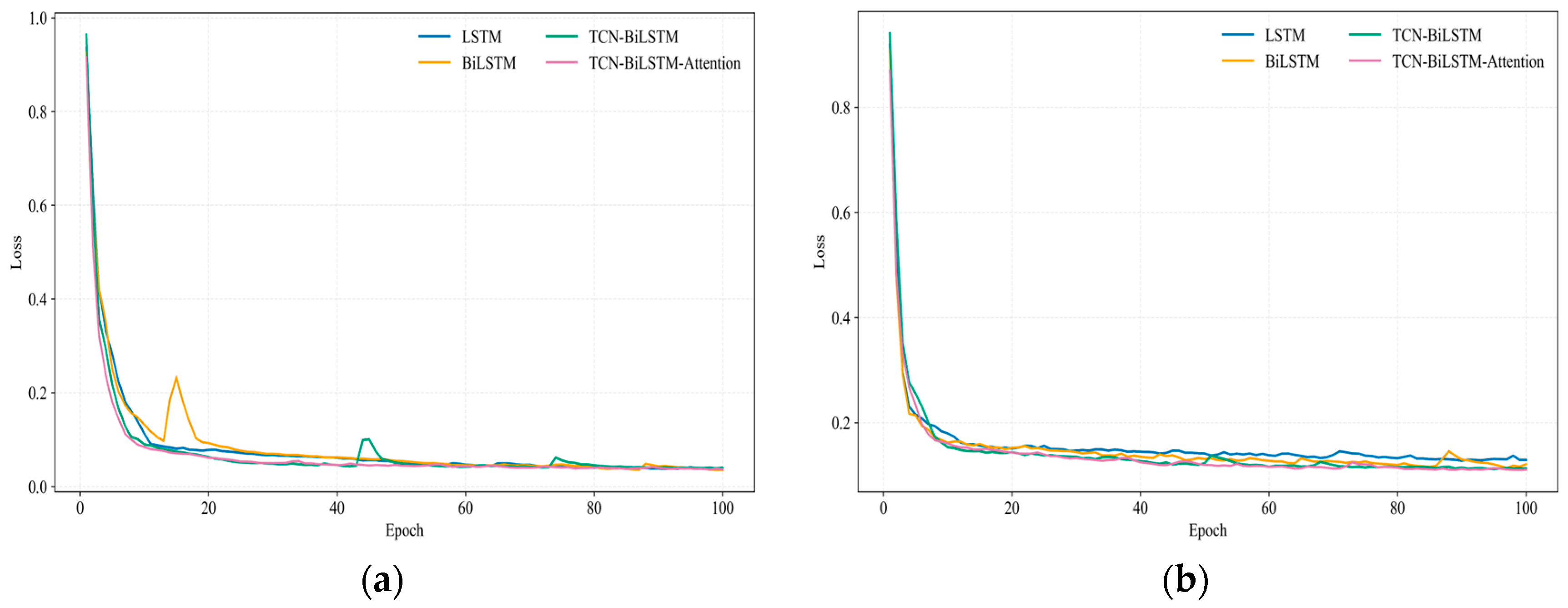

To evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed prediction model, it was compared with three benchmark models: LSTM, BiLSTM, and TCN-BiLSTM. To ensure the accuracy of the model comparison, a batch size of 256 for model input, the random seed count is 42, and the Adam optimizer is used. Model hyperparameters are one factor influencing model robustness [

42]. Therefore, the commonly used parameter optimizer hyperopt was employed for parameter tuning [

43]. For detailed information on the specific parameters of the prediction models used in the experiments, please refer to

Table 4.

All experiments were conducted using a PyTorch 2.7.1 + CUDA 12.8 environment. The platform hardware specifications are as follows: Operating System: Windows 10, Processor: Intel Core i5-12490F, clocked at 4.6 GHz, Graphics Card: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5070 Ti (16GB), CPU: 64 GB.