Assessment of Blast Furnace Slags as a Potential Catalyst in Ozonation to Degrade Bezafibrate: Degradation Study and Kinetic Study via Non-Parametric Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

Blast Furnace Slag Application in Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

2.2. Blast Furnace Slag Source

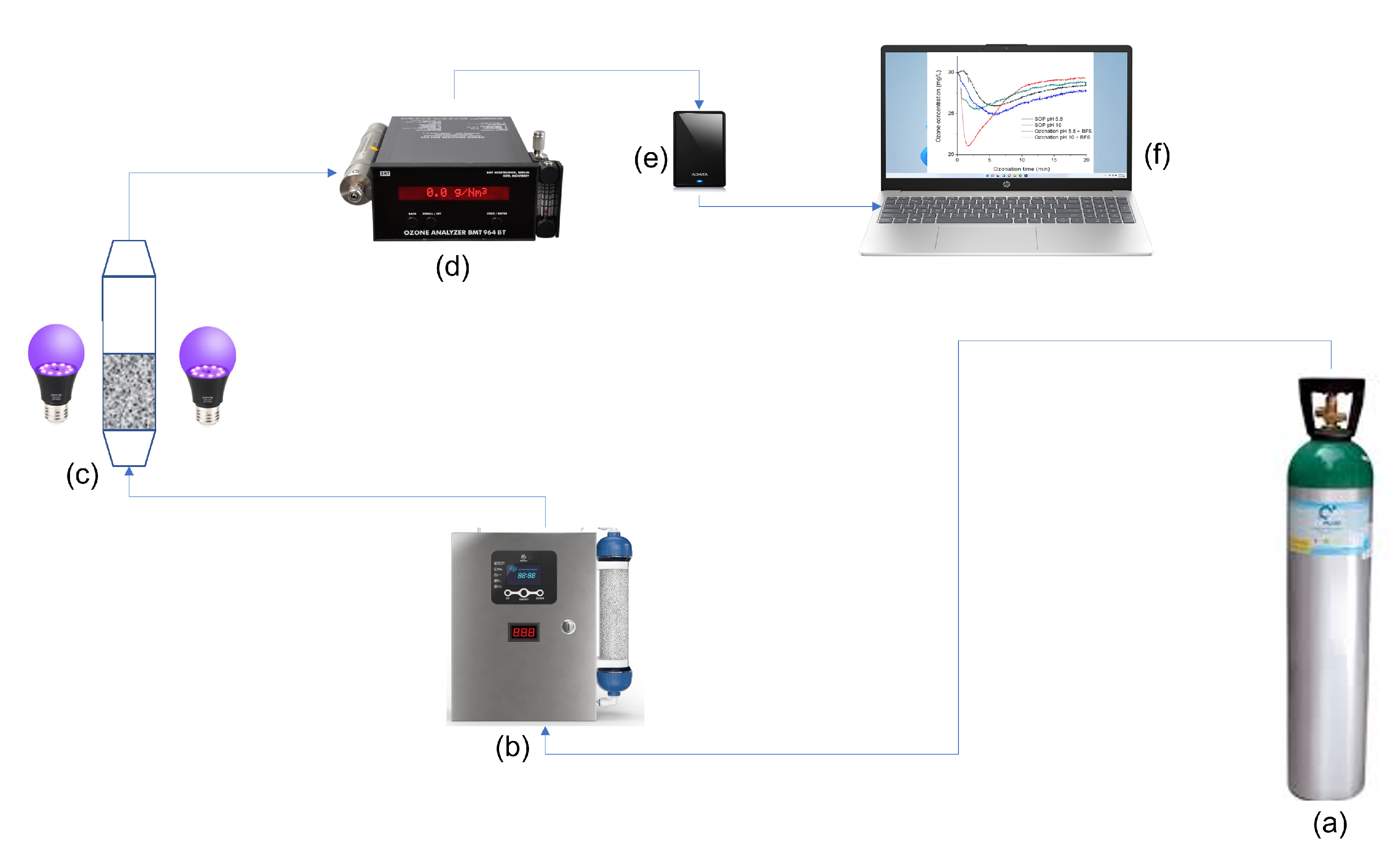

2.3. Ozonation Procedure

2.4. Analytic Method Analysis

2.5. Non-Parametric Modeling of BZF Degradation to Determine the Ozonation Kinetics

3. Results and Discussion

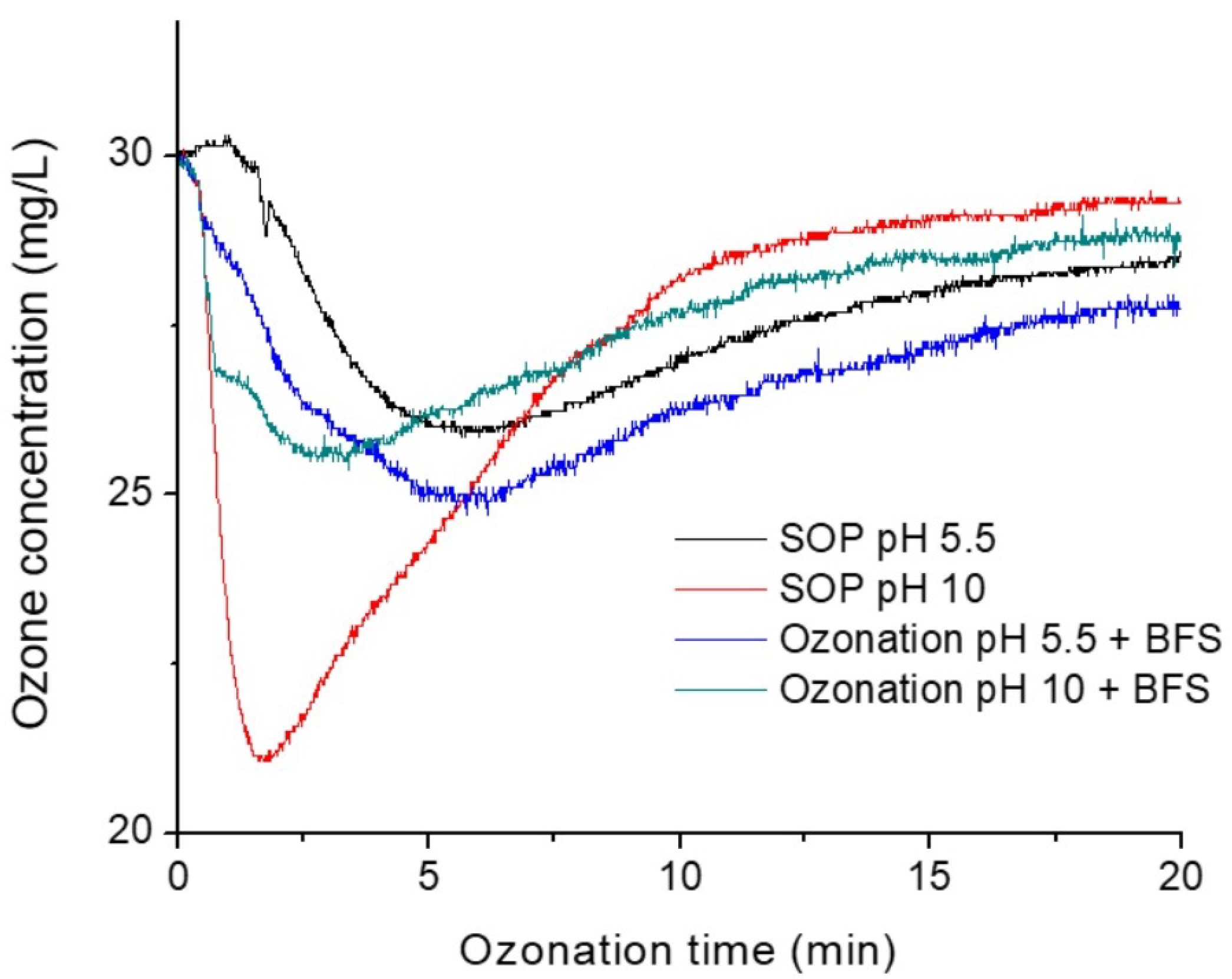

3.1. Ozone Consumption and pH Effect

- The ozone molecule (EV: +2.07 V) reacts with hydroxyl ion , obtained as the main products of hydroperoxyl ion and molecular oxygen.

- The next step is the ion hydroperoxyl dissociation into superoxide ion and a proton.

- Then, the ozone reacts with the superoxide ion, yielding the ozonide radical and molecular oxygen.

- Finally, the ozonide radical reacts with water molecule, producing hydroxyl radicals (EV: +2.80 V), hydroxyl ions (EV: +1.50 V) and molecular oxygen.

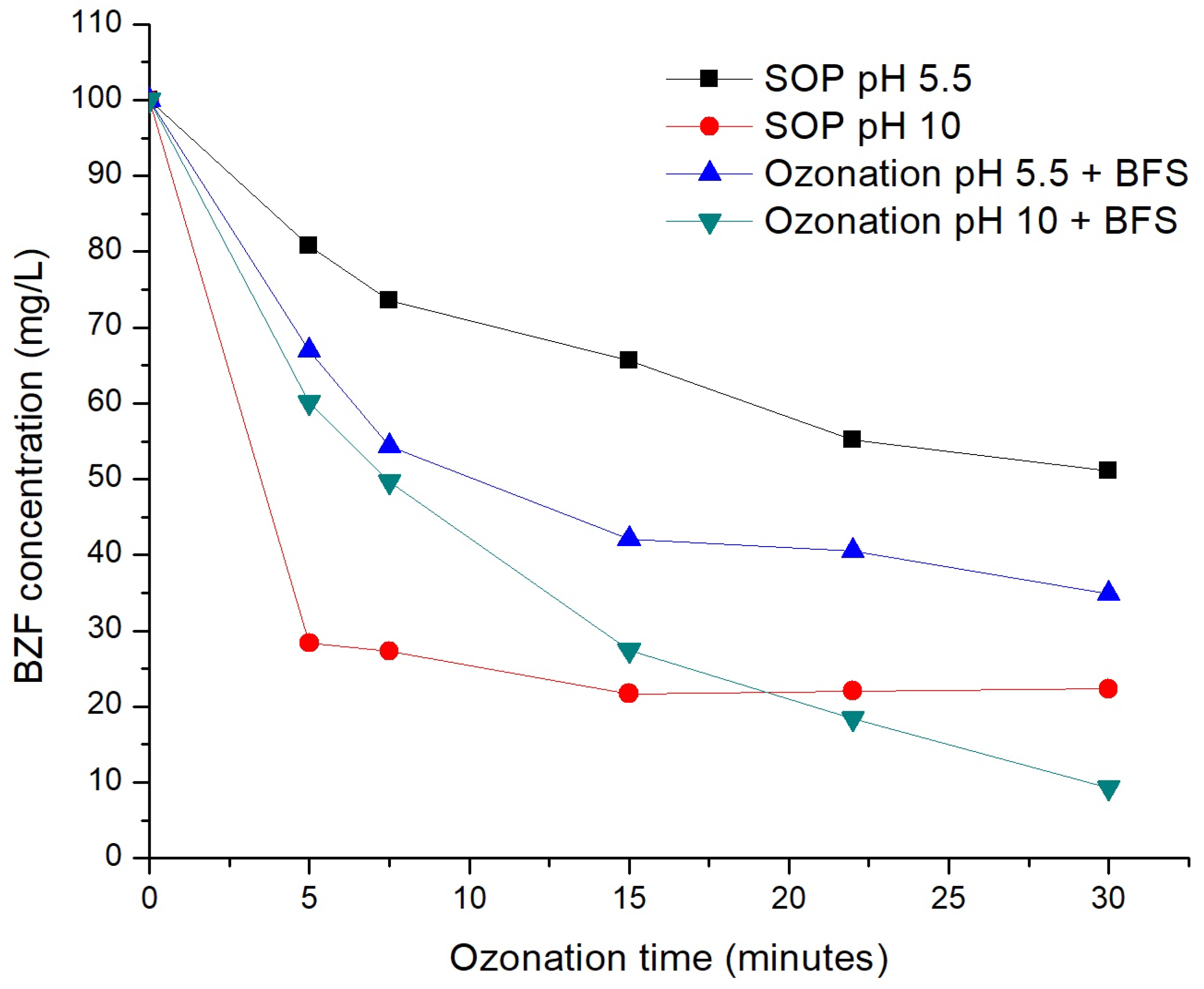

3.2. Bezafibrate Decomposition Efficiency and pH Effect

- 1.

- Ozone adsorption on the BFS surface: the gaseous ozone is absorbed on the BFS surface.

- 2.

- Decomposition of the ozone adsorbed: the ozone molecule decomposes into molecular oxygen and one reactive oxygen atom, generating reactive species on the BFS surface. The atomic oxygen obtained is highly reactive and it can participate in other reactions.

- 3.

- Oxidation of CaO by oxygen atom: this reaction forms calcium peroxide (CaO2, EV: + 0.70 V).

- 4.

- Molecular oxygen desorption: de oxygen is desorbing from the BFS surface, regenerating CaO molecules, ensuring that the BFS surface is available for new ozone molecules.

- 1.

- Ozone adsorption on BFS MnO2 surface. The gaseous ozone adheres to the BFS surface where MnO2 lies, where the following reactions occurs:

- 2.

- Decomposition of adsorbed ozone. The ozone decomposes in molecular oxygen and one reactive oxygen atom; in this stage species highly reactive are generated to react with MnO2 and other molecules adsorbed in the BFS surface.

- 3.

- MnO2 oxidation: the reactive oxygen atom generated oxidizes MnO2, leading to the formation of a higher valency manganese oxide, Mn2O5(EV= + 1.2 V).

- 4.

- Molecular oxygen desorption: MnO2 is regenerated to allow the reaction cycle to continue, adsorbing more ozone.

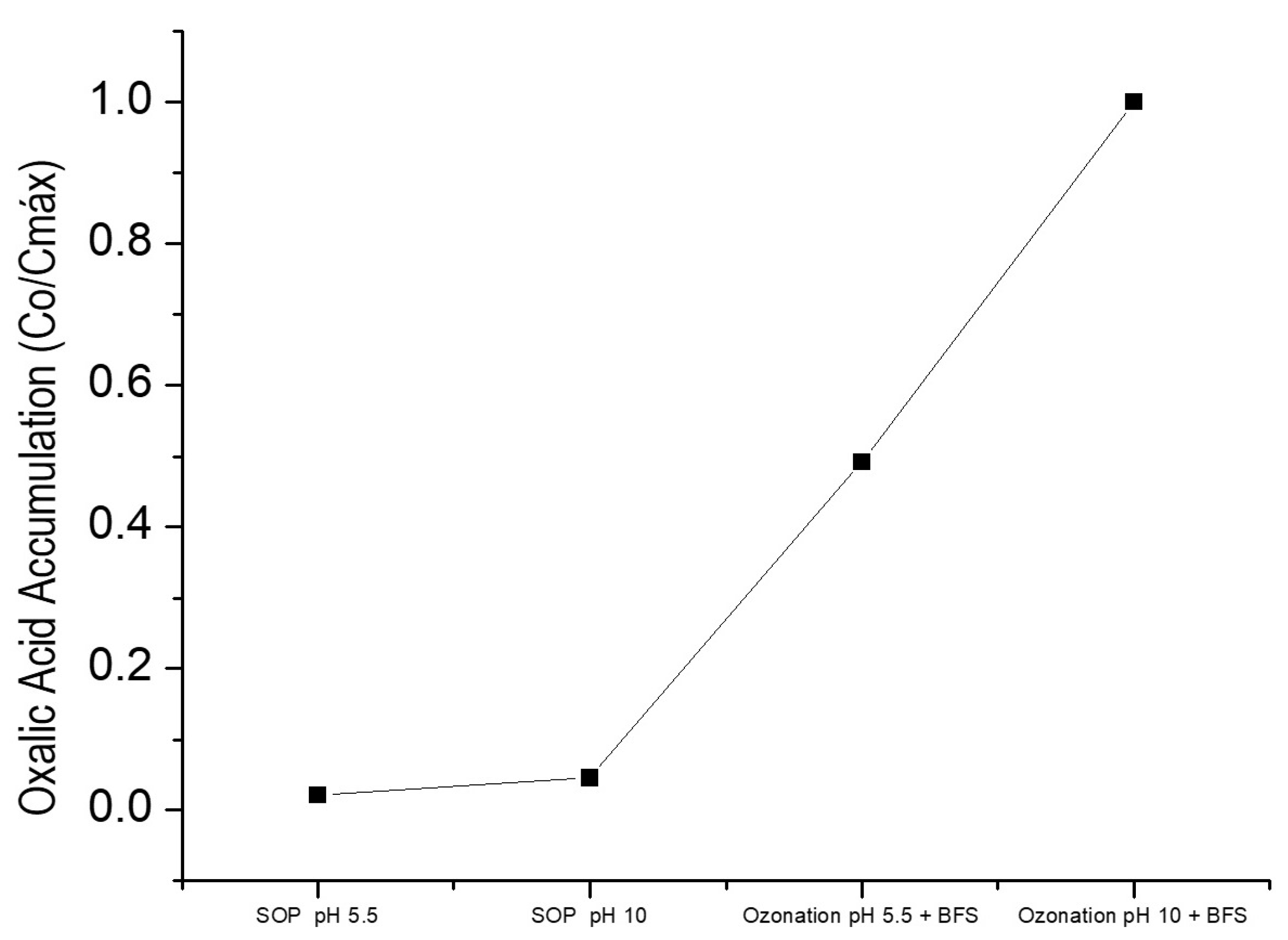

3.3. Final Compound Identification

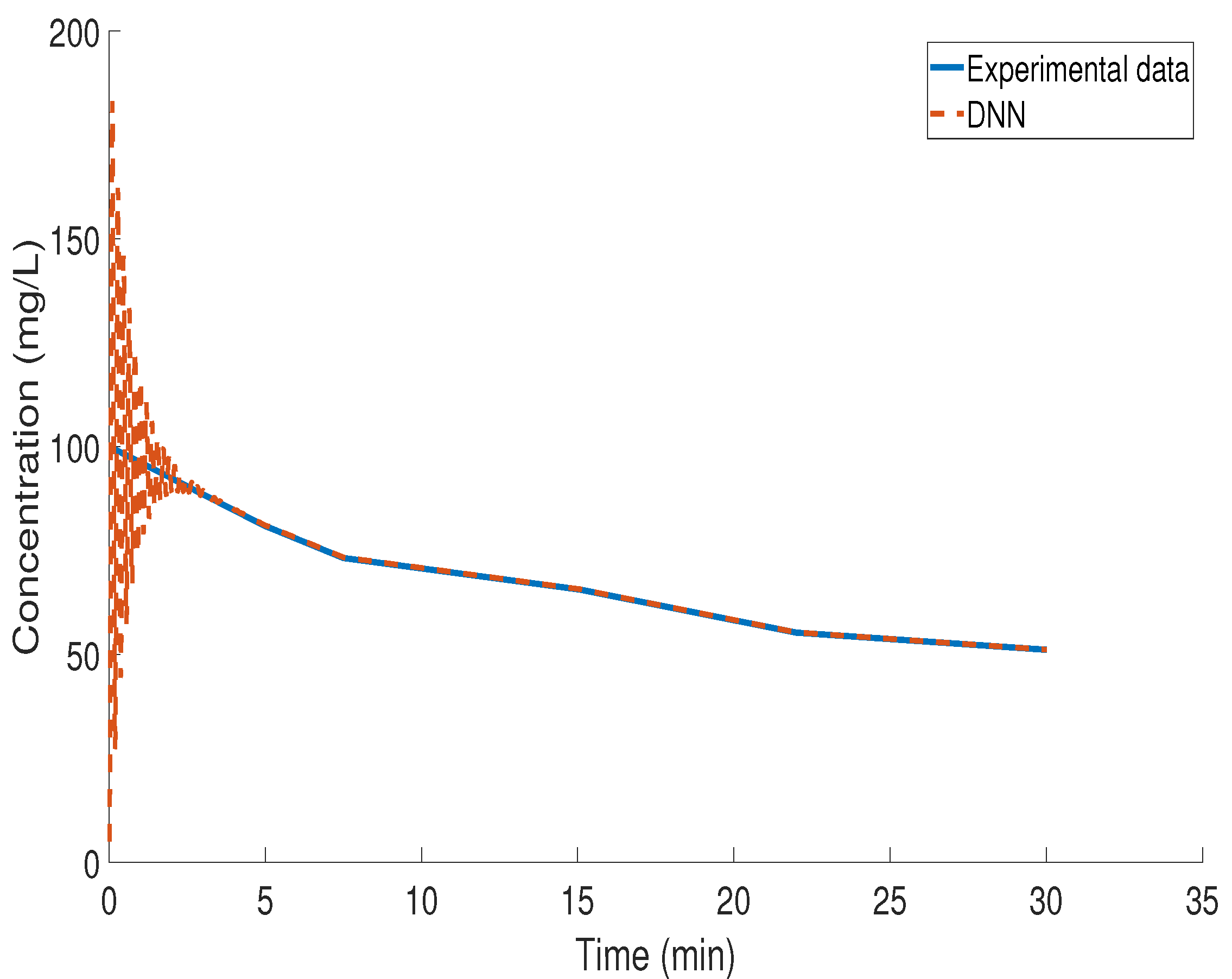

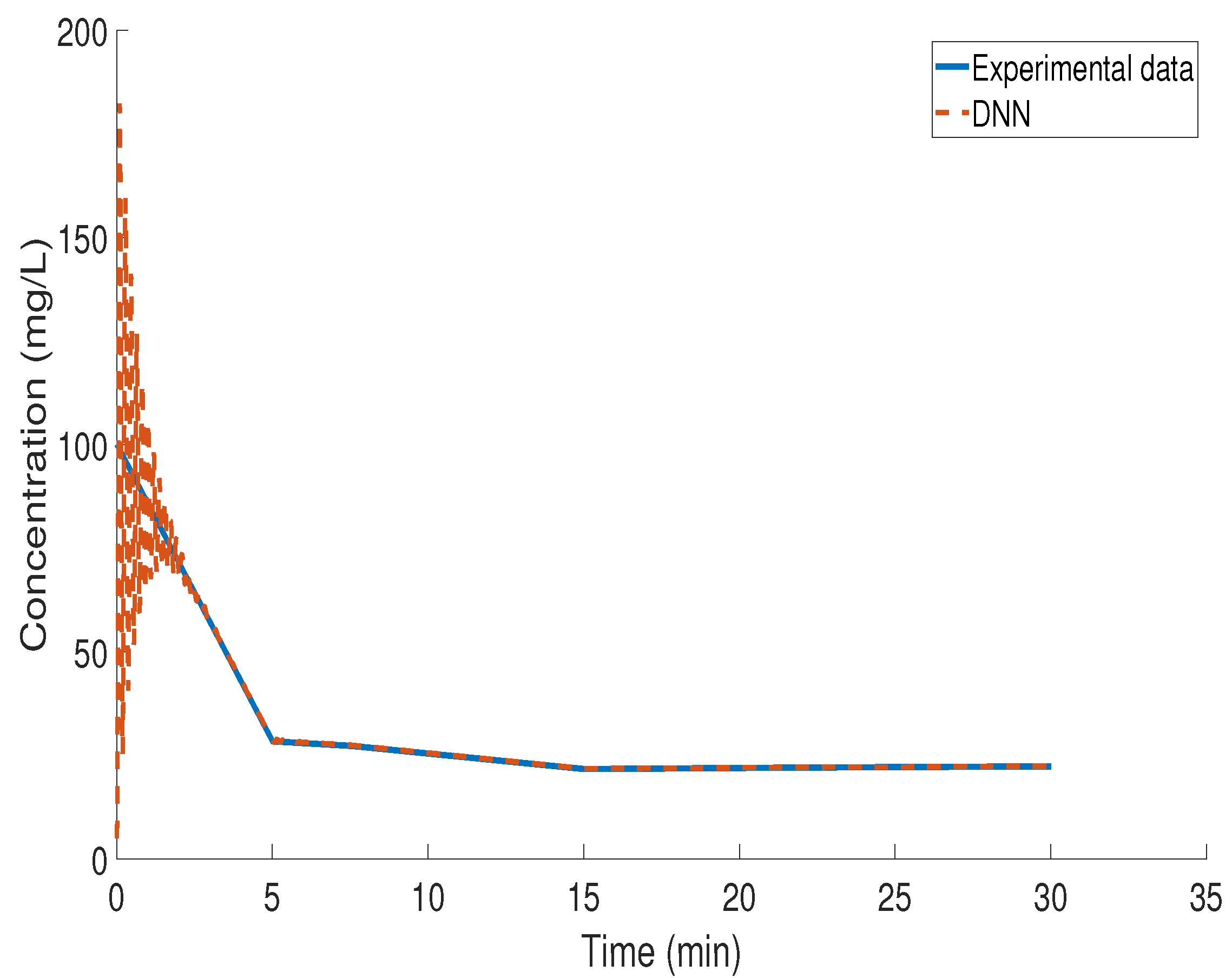

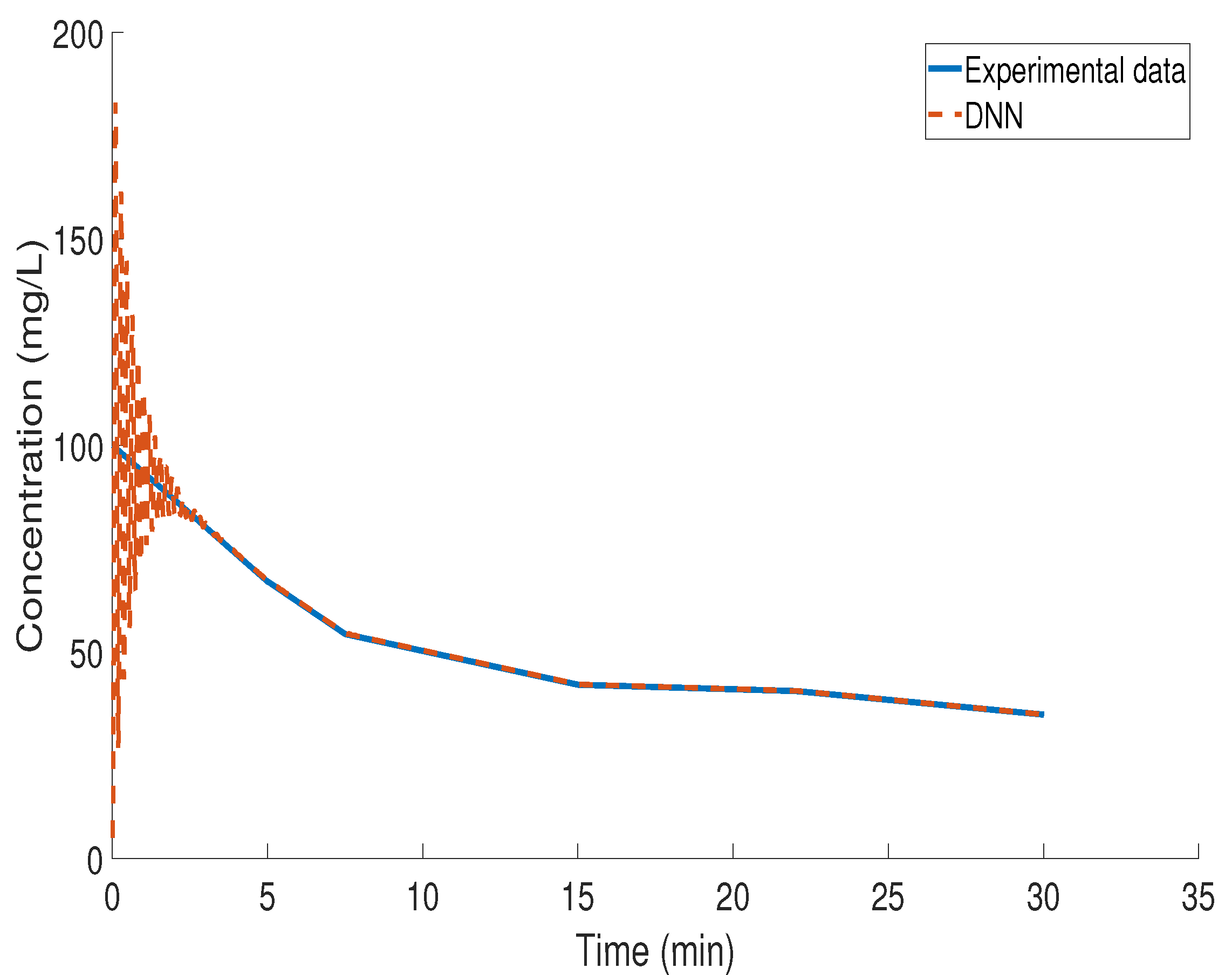

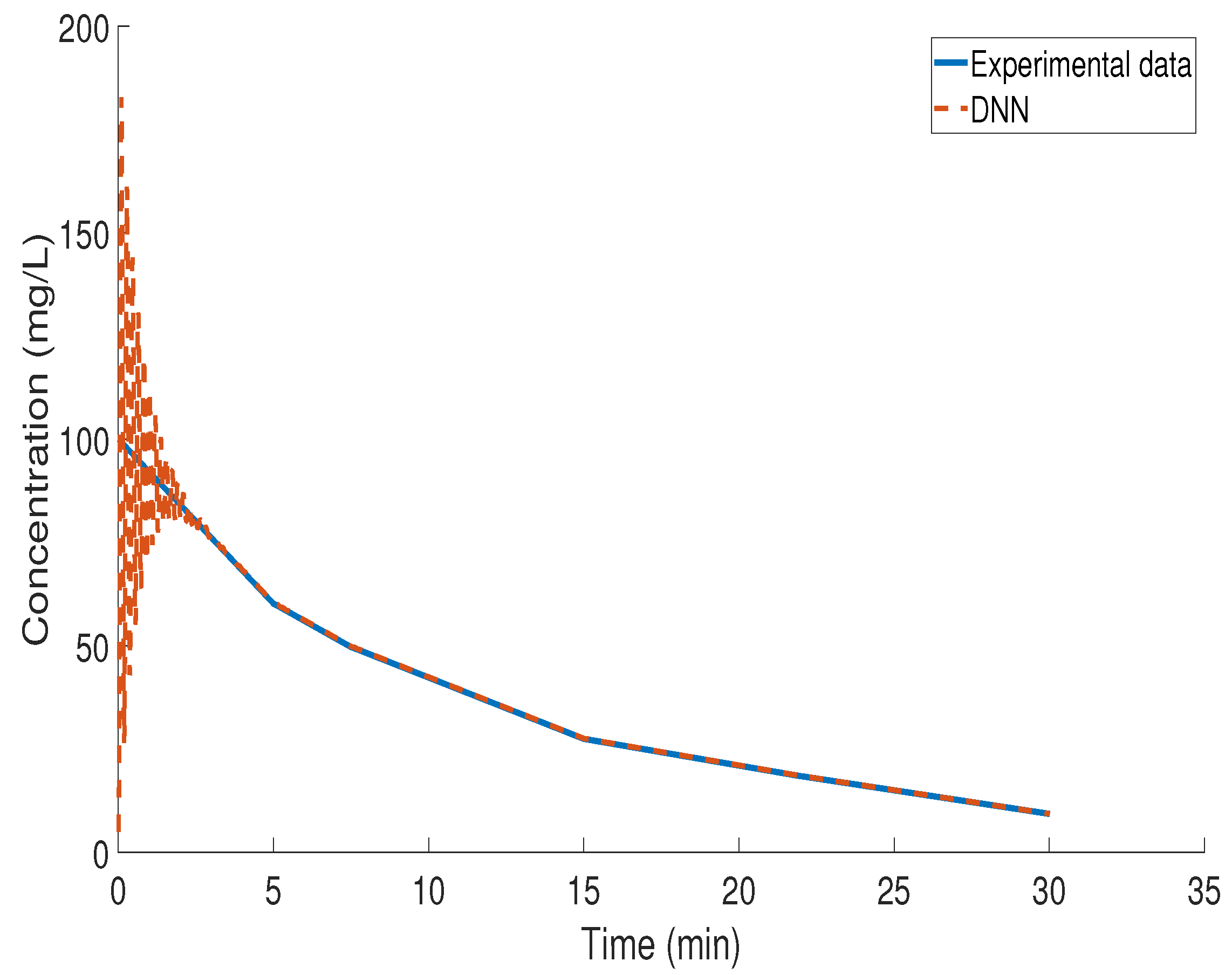

3.4. Kinetic Study of BZF Decomposition via LSTM Modeling

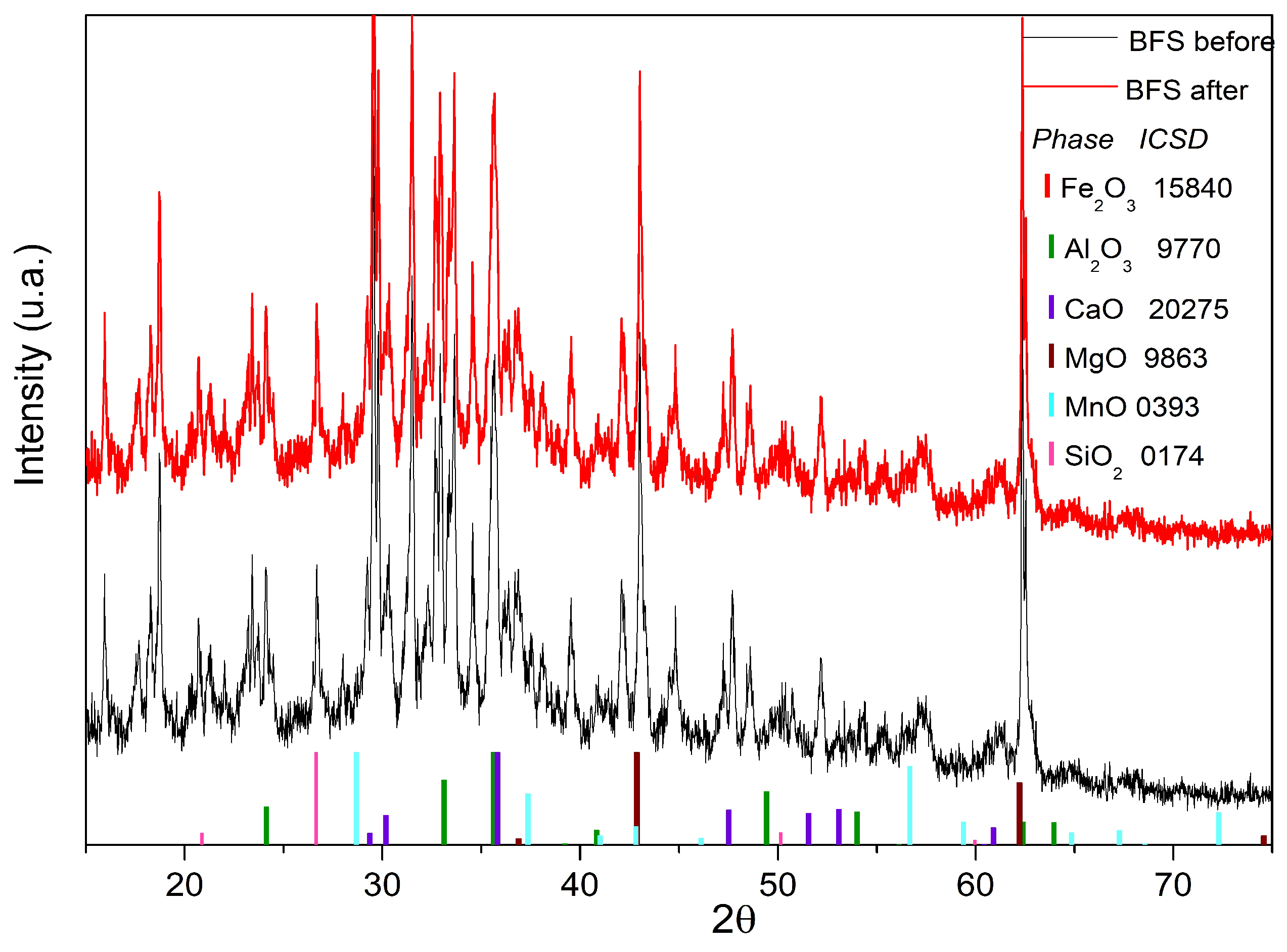

3.5. Blast Furnace Slag XRD Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOP | Advanced oxidation processes |

| BFS | Blast furnace slag |

| BZF | Bezafibrate |

| BOD5 | Biological oxygen demand at 5th day |

| DNN | Differential neural networks |

| WWT | Water and wastewater treatment |

References

- Agrawal, S.; Dhawan, N. Evaluation of red mud as a polymetallic source—A review. Miner. Eng. 2021, 171, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Guo, Z.; Pan, J.; Zhu, D.; Yang, C.; Xue, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, D. Comprehensive review on metallurgical recycling and cleaning of copper slag. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.j.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Fang, Q.; Wang, B.; Ni, H.w. Effect of process parameters on dry centrifugal granulation of molten slag by a rotary disk atomizer. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2021, 28, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Prakash, S.; Reddy, P.; Misra, V.N. An overview of utilization of slag and sludge from steel industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 50, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teir, S.; Eloneva, S.; Fogelholm, C.J.; Zevenhoven, R. Dissolution of steelmaking slags in acetic acid for precipitated calcium carbonate production. Energy 2007, 32, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Mu, T.; Yu, Q. A novel synergistic method on potential green and high value-added utilization of blast furnace slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Nie, Z.; Cui, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. Environmental impact analysis of blast furnace slag applied to ordinary Portland cement production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 120, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oge, M.; Ozkan, D.; Celik, M.B.; Gok, M.S.; Karaoglanli, A.C. An overview of utilization of blast furnace and steelmaking slag in various applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 11, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, N.M.; Parsons, M.B.; Seal, R.R., II. Characteristics and environmental aspects of slag: A review. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 57, 236–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, S.; Yamamoto, T. Blast furnace slag can effectively remediate coastal marine sediments affected by organic enrichment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J.; Belyaeva, O.; Kingston, G. Evaluation of industrial wastes as sources of fertilizer silicon using chemical extractions and plant uptake. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013, 176, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Seo, S.G.; Jung, S.C. Preparation of high purity nano silica particles from blast-furnace slag. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 1901–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, J.; Kapelyushin, Y.; Mishra, D.P.; Ghosh, P.; Sahoo, B.; Trofimov, E.; Meikap, B. Utilization of ferrous slags as coagulants, filters, adsorbents, neutralizers/stabilizers, catalysts, additives, and bed materials for water and wastewater treatment: A review. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, B.; Song, W.; Cooper, W.J.; Greaves, J.; Jeong, J. Free-radical-induced oxidative and reductive degradation of fibrate pharmaceuticals: Kinetic studies and degradation mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambropoulou, D.; Hernando, M.; Konstantinou, I.; Thurman, E.; Ferrer, I.; Albanis, T.; Fernández-Alba, A. Identification of photocatalytic degradation products of bezafibrate in TiO2 aqueous suspensions by liquid and gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1183, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, B.; Qi, F.; Sun, D.; Chen, Z. Degradation of bezafibrate in wastewater by catalytic ozonation with cobalt doped red mud: Efficiency, intermediates and toxicity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 152, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, M.; Nardelli, A.; Pascarella, L.; Rubino, M.; Parrella, A. Toxic and genotoxic impact of fibrates and their photoproducts on non-target organisms. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewes, J.E.; Heberer, T.; Reddersen, K. Fate of pharmaceuticals during indirect potable reuse. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, C.M.; Chairez, I.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Tiznado, H.; Santillán, R.; Arrieta, D.; Poznyak, T. Inhibition effect of ethanol in naproxen degradation by catalytic ozonation with NiO. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 14822–14833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Z.; He, Z.; Zhang, A.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X. Impacts of morphology and crystallite phases of titanium oxide on the catalytic ozonation of phenol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3913–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, W.; Croué, J.P. Catalytic ozonation of oxalate with a cerium supported palladium oxide: An efficient degradation not relying on hydroxyl radical oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9339–9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhate, C.V.; Srivastava, J. Recent advances in ozone-based advanced oxidation processes for treatment of wastewater—A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.N.; Ghosh, P.C.; Vaidya, A.N.; Mudliar, S.N. Hybrid ozonation process for industrial wastewater treatment: Principles and applications: A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 35, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, J.O.; Fatoba, O.O.; Madzivire, G.; Petrik, L.F. A review of combined advanced oxidation technologies for the removal of organic pollutants from water. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D. Reinforce of hydrotalcite-like loaded TiO2 composite material prepared by Ti-bearing blast furnace slag for photo-degradation of tetracycline. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 36, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangappa, H.S.; Mon, P.P.; Herath, I.; Madras, G.; Lin, C.; Subrahmanyam, C. Modeling Tetracycline Adsorption onto Blast Furnace Slag Using Statistical and Machine Learning Approaches. Sustainability 2024, 16, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Suo, N.; Long, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Y. Preparation of particle electrodes from manganese slag and its degradation performance for salicylic acid in the three-dimensional electrode reactor (TDE). Chemosphere 2019, 216, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Gao, H.; Liao, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D. A novel slag-based Ce/TiO2@LDH catalyst for visible light driven degradation of tetracycline: Performance and mechanism). J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 901, 163525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasce, L.; Bocero, F.; Ramos, C.; Inchaurrondo, N. Enhanced mineralization of bisphenol A by electric arc furnace slag: Catalytic ozonation. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 16, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzate-Salgado, S.Y.; Morales-Pérez, A.A.; Solís-López, M.; Ramírez-Zamora, R.M. Evaluation of metallurgical slag as a Fenton-type photocatalyst for the degradation of an emerging pollutant: Diclofenac. Catalysis Today 2016, 266, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, L.; Sabelfeld, M.; Geissen, S.U.; Bousselmi, L. Catalytic ozonation of model organic compounds in aqueous solution promoted by metallic oxides. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, L.; Chen, F.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, J.; Yin, C. Application of heterogeneous catalytic ozonation in wastewater treatment: An overview. Catalysts 2023, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wei, C.; Wang, Y.; Wen, G. Application of metal oxide catalysts for water treatment—A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 401, 124644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A.S.; Sanchez, E.N.; Yu, W. Differential Neural Identification, State Estimation and Trajectory Tracking; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.C.; Khalil, H.K. Adaptive control of nonlinear systems using neural networks. Int. J. Control 1992, 55, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairez, I.; Poznyak, A.; Poznyak, T. Reconstruction of dynamics of aqueous phenols and their products formation in ozonation using differential neural network observers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 5855–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairez, I.; Chalanga, A.; Poznyak, A.; Spurgeon, S.; Poznyak, T. Simultaneous state and parameter estimation method for a conventional ozonation system. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 167, 108018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, T.; García, A.; K, E. Ozone application for the people health state monitoring by the total unsaturation index determination. Ozonoterapia 2008, 1, 15–323. [Google Scholar]

- Razumovskii, S. Reactions of ozone with aromatic compounds. In Chemical Kinetics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Staehelin, J.; Hoigne, J. Decomposition of ozone in water: Rate of initiation by hydroxide ions and hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982, 16, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gunten, U. Ozonation of drinking water: Part I. Oxidation kinetics and product formation. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Cao, X.; Liu, R.; Yun, J. Simultaneously removal of phosphorous and COD for purification of organophosphorus wastewater by catalytic ozonation over CaO. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Luo, D.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Cheng, W.; Ge, S. Ozonation of acid red 18 wastewater using O3/Ca(OH)2 system in a micro bubble gas-liquid reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Hayhurst, A. Reaction between gaseous sulfur dioxide and solid calcium oxide: Mechanism and kinetics. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1996, 7, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhu, T.; Li, J.L.; Ding, J. Kinetics and mechanism of heterogeneous oxidation of sulfur dioxide by ozone on the surface of calcium carbonate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 2453–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, R.; Insola, A.; Caprio, V.; Marotta, R.; Tufano, V. The use of manganese dioxide as a heterogeneous catalyst for oxalic acid ozonation in aqueous solution. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1996, 138, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Graham, N.J. Degradation of atrazine by manganese-catalysed ozonation—Influence of radical scavengers. Water Res. 2000, 34, 3822–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Si, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. A novel (γ)-like MnO2 catalyst for ozone decomposition in high humidity conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Lu, Y.; Yin, X. Catalytic Decomposition of Ozone by CuO/MnO2-Performance, Kinetics and Application Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2015, 121, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, K.; Jiang, P.; Wang, G.; Miao, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Simple hydrothermal preparation of (α)-, (β)-, and (γ)-MnO2 and phase sensitivity in catalytic ozonation. RSC Adv. 2014, 74, 39167–39173. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Type of Slag | Pollutant | Operating Conditions | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Song, 2020) [25] | Composite material of hydrotalcite-like loaded TiO2 (TiO2@ Mg-Al, LDH), prepared from Ti-bearing blast furnace slag (Ti-BFS) | Tetracycline (TC) | TC concentration: 50 mg/L, Ultraviolet lamp 0–5000 W | Ti-bearing composites mass 0.10 mg TiO2@ Mg-Al LDH was layered double hydroxide loading TiO2 structure and doped with metal elements like Fe, Mn, etc., which confers more HO•− h+ density on the surface of TiO2@Mg-Al LDH, and aromatic ring of TC can be attacked more effectively. The TC efficacy removal was up to 90% within 120 min, reaching up to 72% of mineralization degree. |

| (Rangappa, 2024) [26] | Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) | Tetracycline (TC) | TC adsorption in GGBS, TCe concentration 20–100 mg/L, 50 mL of aqueous solution at 25 ± 3 °C room temperature, 6000 rpm/10 min, Contact time: 180 min | The higher removal of TC (68%) at an optimum adsorbent and pollutant dosage of 50 mg and 20 ppm. |

| (Chen, 2019) [27] | Manganese slag | Salicylic acid | Three-dimensional electrode reactor (TDE) Cell voltages: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 y 30 V pH: 1.00, 3.00, 5.00, 7.00, 9.00, 11.00 Salicylic acid concentration: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5 and 0.70 mg/L | The manganese slag as particle electrodes had been successfully loaded on the Cu/Fe and applied on the TDE to degrade Salicylic acid, reaching 76.9% of rate removal. Acetic acid was the main final product obtained. |

| (Song, 2022) [28] | Hydrotalcite-like photocatalytic material (denoted CeTL) was prepared from titanium-bearing blast furnace slag (Ti-BFS) | Tetracycline (TC) | Tetracycline (TC) was used to evaluate the photochemical catalytic performance of CeTL under a 300 W Xenon lamp. The catalyst of 20 mg was accurately weighed and added to the TC aqueous solution (20 ppm). | The degradation rate of (TC) by CeTL reached 92.8% after 90 min of illumination. The results of XRD, BET, UV-DRS, VB-XPS, and active species capture indicated that this might be the synergistic effect of good adsorption capacity and enhanced photocatalysis. |

| (Fasce, 2023) [29] | Electric arc furnace slag (EAFS) | Bisphenol A (BPA) | BPA concentration: 20 mg/L Temperature of room: 23–24 °C 3 h/1 L Ozone gas flow: 700 mL/min | Ozone concentration: 10 mL/L EAFS improved the mineralization degree of BPA at acidic and alkaline conditions for those achieved in single ozonation processes. The high TOC conversion reached at alkaline pH (80%) was due to the generation of HO•− promoted by OH− combined with precipitation reactions caused by Ca oxides. The improvement in the mineralization level at pH 3 (63%) was attributed to the activity of leached species, mostly Fe and Mn cations. |

| (Arzate-Salgado, 2016) [30] | Two metallurgical wastes: one from the copper (COB) and other from the steel (MIT) industries, as Fenton-type photocatalysts | Diclofenac (DCF) | Xe arc lamp at 300–800 nm, and an air-cooled Xe lamp system with 5–6% photon emissions between 290 and 400 nm. Diclofenac concentration of 500 mg/L Stirrer agitated at 250 rpm at 35 °C | Based on the degradation rate constants of DCF, the COB/H2O2/simulated sunlight system showed a better performance than the COB/simulated sunlight system due to the contribution of hydrogen peroxide in the •OH radical production. Complete depletion of DCF was obtained after 90 and 150 min of reaction for the initial concentrations of 30 and 120 mg/L, respectively. The highest mineralization (87%) of this drug was achieved after 300 min of reaction time. |

| System | Initial pH |

|---|---|

| Simple Ozonation Process (SOP) | 5.5 |

| Simple Ozonation Process (SOP) | 10 |

| BFS + Ozonation Process | 5.5 |

| BFS + Ozonation Process | 10 |

| Physic | Chemical |

|---|---|

| Solid | FeO: 40% |

| Color gray | CaO: 22% |

| Density: 1.67 kg/m3 | SiO2 14% |

| Hardness: 7 in Mohs scale | MgO: 8.5% |

| Particle size: 3/8–¾ in | Al2O3: 5.3% |

| MnO2: 1.6% |

| System | Ozone Consumed (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| SOP pH 5.5 | 75.64 |

| SOP pH 10 | 85.27 |

| Ozonation pH 5.5 + BFS | 93.63 |

| Ozonation pH 10 + BFS | 68.12 |

| Reaction System | Reaction Rate Constant, L·mol·s−1 |

|---|---|

| Oz pH 5.5 | 145.67 |

| Oz pH 10.0 | 1489.98 |

| Oz pH 5.5 + BFS | 645.67 |

| Oz pH 10.0 + BFS | 1689.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galina-Licea, A.; Alfaro-Ponce, M.; Chairez, I.; Reyes, E.; Perez-Martínez, A. Assessment of Blast Furnace Slags as a Potential Catalyst in Ozonation to Degrade Bezafibrate: Degradation Study and Kinetic Study via Non-Parametric Modeling. Processes 2024, 12, 1998. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12091998

Galina-Licea A, Alfaro-Ponce M, Chairez I, Reyes E, Perez-Martínez A. Assessment of Blast Furnace Slags as a Potential Catalyst in Ozonation to Degrade Bezafibrate: Degradation Study and Kinetic Study via Non-Parametric Modeling. Processes. 2024; 12(9):1998. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12091998

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalina-Licea, Alexandra, Mariel Alfaro-Ponce, Isaac Chairez, Elizabeth Reyes, and Arizbeth Perez-Martínez. 2024. "Assessment of Blast Furnace Slags as a Potential Catalyst in Ozonation to Degrade Bezafibrate: Degradation Study and Kinetic Study via Non-Parametric Modeling" Processes 12, no. 9: 1998. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12091998

APA StyleGalina-Licea, A., Alfaro-Ponce, M., Chairez, I., Reyes, E., & Perez-Martínez, A. (2024). Assessment of Blast Furnace Slags as a Potential Catalyst in Ozonation to Degrade Bezafibrate: Degradation Study and Kinetic Study via Non-Parametric Modeling. Processes, 12(9), 1998. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12091998