Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Eliciting Perceived Willingness to Take Financial Risk (PWTFR)

When thinking of your financial investments, how willing are you to take risks? Please use a 10-point scale, where 1 means “Not At All Willing” and 10 means “Very willing”.

2.3. Eliciting Revealed Incentivized Risk Preferences (IRRP)

2.4. Financial Literacy Test

3. Empirical Model Specification

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

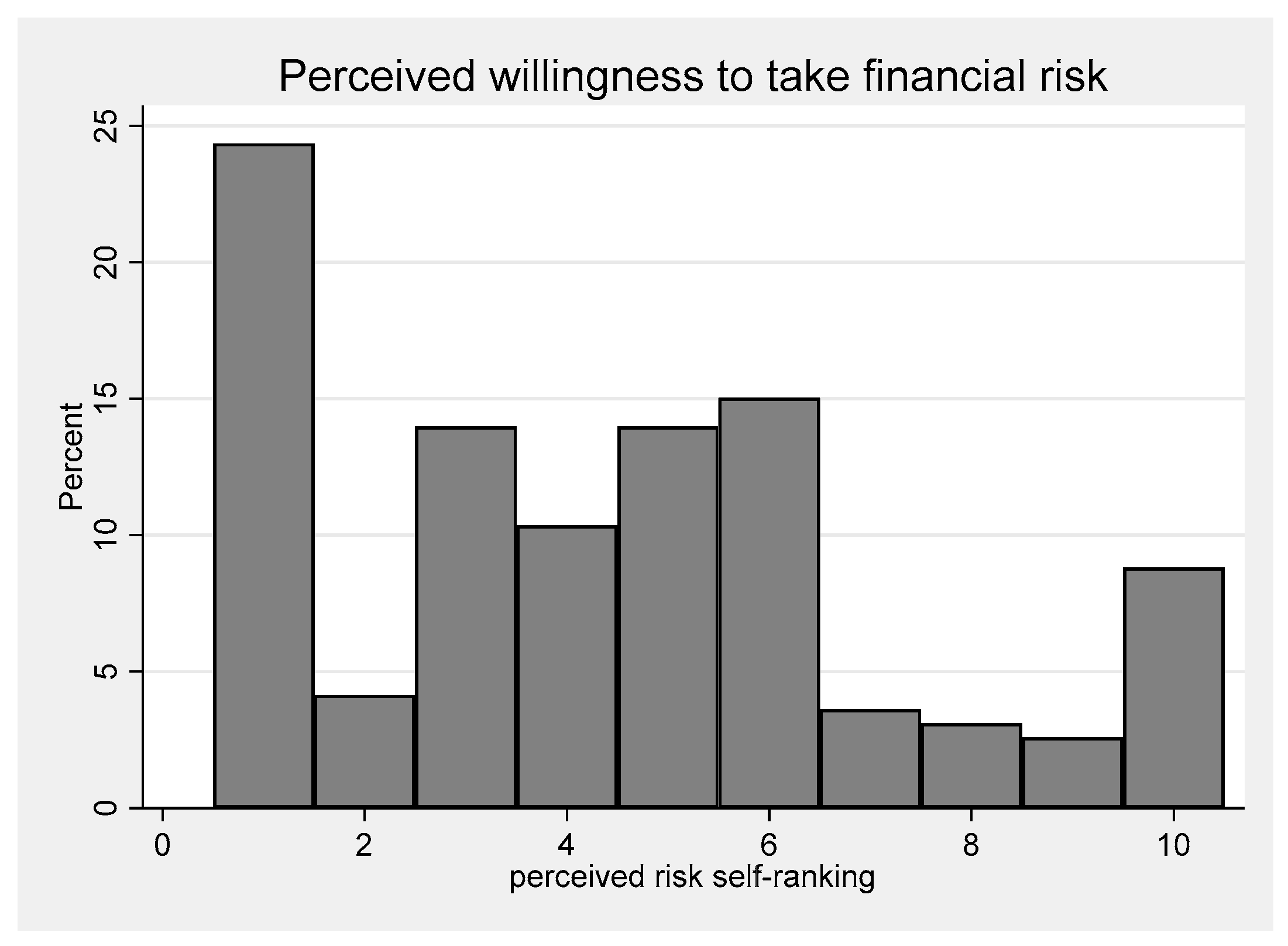

3.2. Perceived Willingness to Take Financial Risk for All Subjects

3.3. Incentivized Revealed Risk Preferences (IRRP)

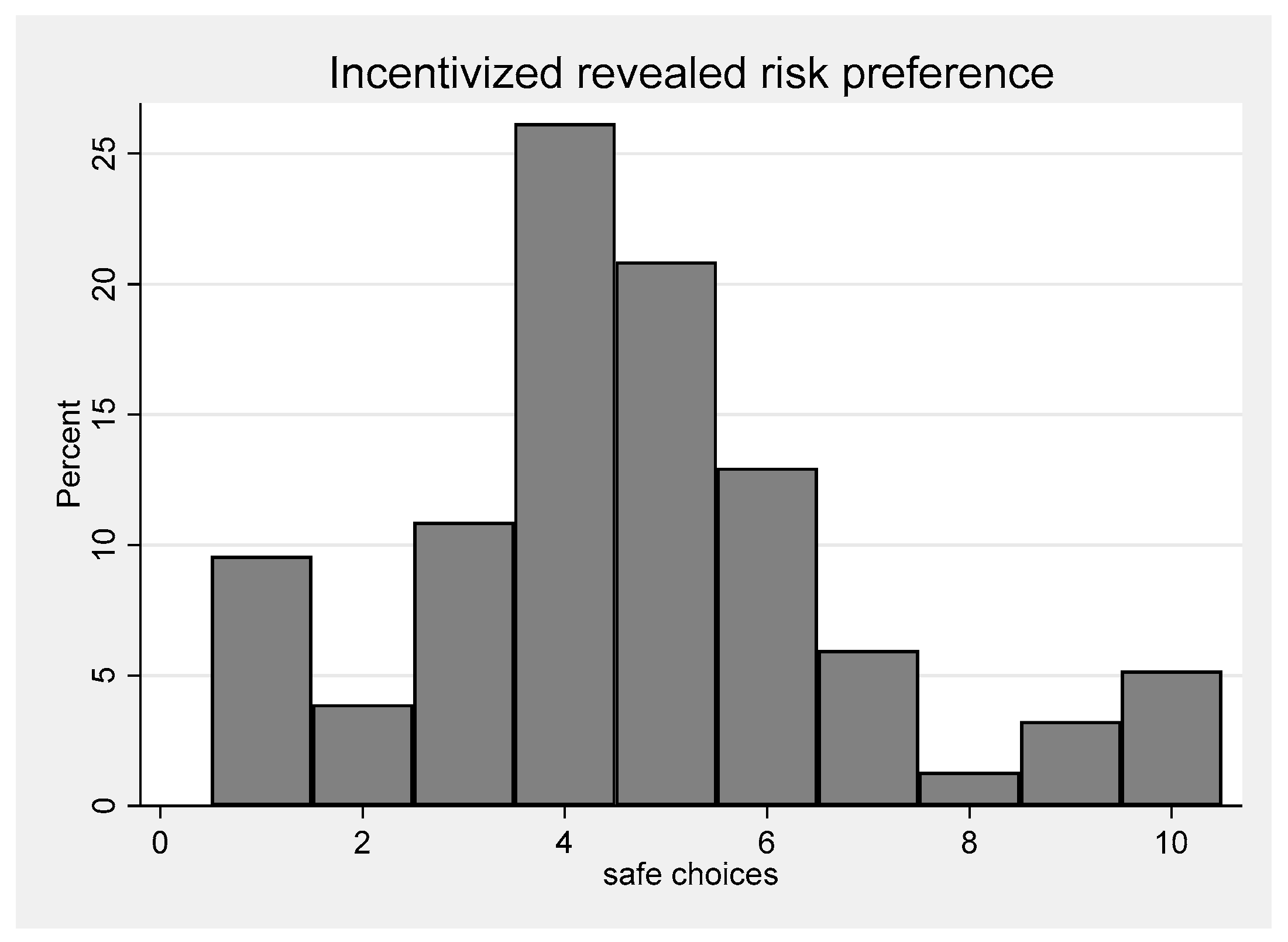

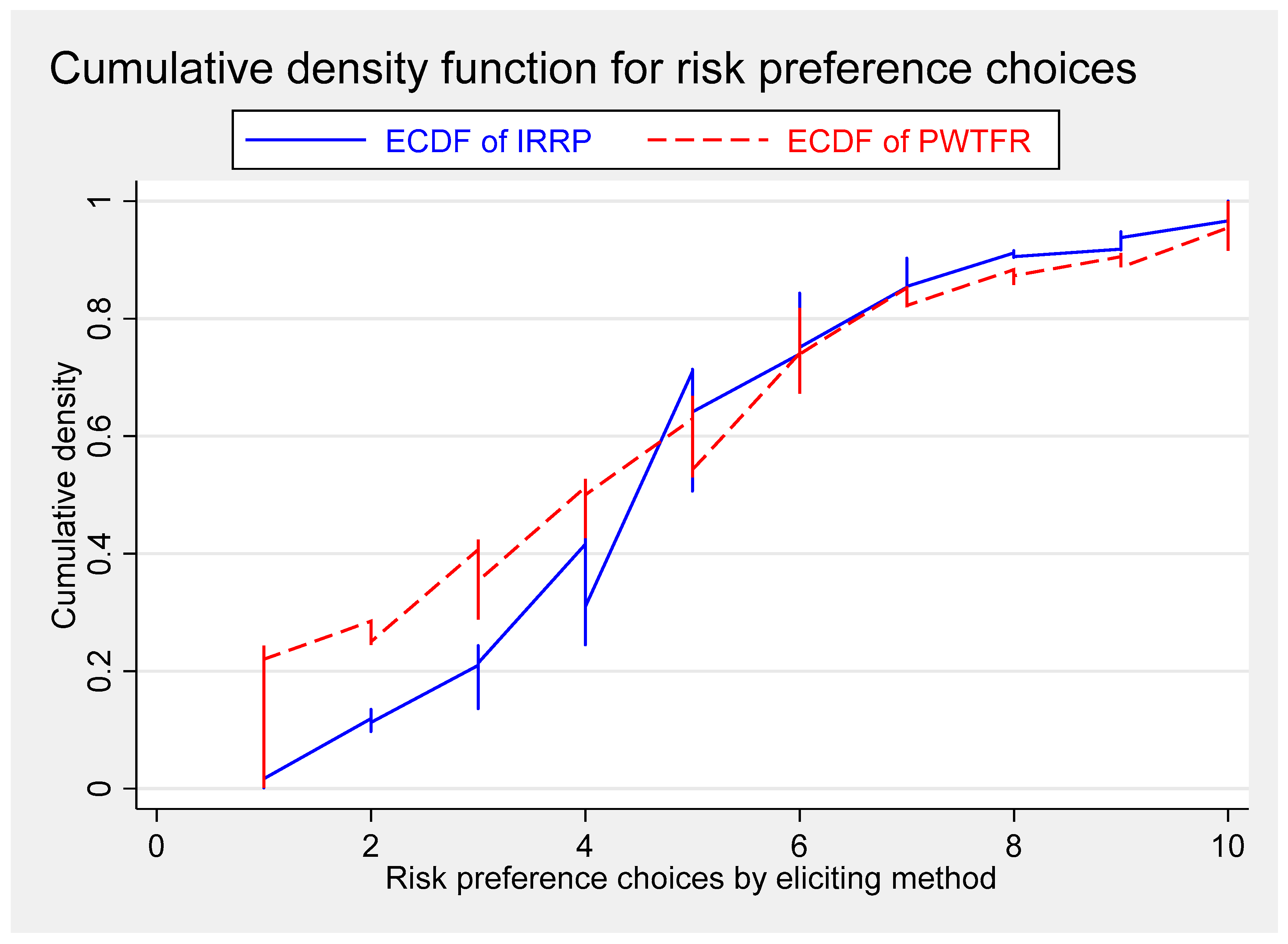

3.4. Cumulative Density Function for PWTFR and IRRP Choices

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Cross Tabulations PWTFR versus IRRP

4.2. T-Test and Partial Correlation Analysis

4.3. Regressions Results

4.3.1. Perceived Willingness to Take Financial Risk on Investments

4.3.2. Incentivized Revealed Risk Preferences (IRRP)

4.3.3. Risk Tolerance Gap

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 2011. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, Sule, Seda Ertac, and Elif Kubilay. 2020. Understanding Gender Differences in Leadership. The Economic Journal 130: 263–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Steffen, Glenn W. Harrison, Morten I. Lau, and E. Elisabet Rutström. 2008. Eliciting Risk and Time Preferences. Econometrica 76: 583–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, Lisa R., and Jennifer M. Mellor. 2009. Are Risk Preferences Stable? Comparing an Experimental Measure with a Validated Survey-Based Measure. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 39: 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arano, Kathleen, Carl Parker, and Rory Terry. 2010. Gender-Based Risk Aversion and Retirement Asset Allocation. Economic Inquiry 48: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, Charles, and Bruce Shearer. 2010. Sorting, Incentives and Risk Preferences: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Economics Letters 108: 345–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Binswanger, Johannes, and Martin Salm. 2017. Does Everyone Use Probabilities? The Role of Cognitive Skills. European Economic Review 98: 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, Michael, Larry V. Hedges, Julian P. T. Higgins, and Hannah R. Rothstein. 2010. A Basic Introduction to Fixed-Effect and Random-Effects Models for Meta-Analysis. Research Synthesis Methods 1: 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgaard, Johan, and Mogens Steffensen. 2020. Eliciting Risk Preferences and Elasticity of Substitution. Decision Analysis 17: 314–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Marco, Jeffrey L. Jordan, and Ragan Petrie. 2018. Children’s Rationality, Risk Attitudes and Field Behavior. European Economic Review 102: 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, Gary, Uri Gneezy, and Alex Imas. 2013. Experimental Methods: Eliciting Risk Preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 87: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csermely, Tamás, and Alexander Rabas. 2016. How to Reveal People’s Preferences: Comparing Time Consistency and Predictive Power of Multiple Price List Risk Elicitation Methods. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 53: 107–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, Thomas, Armin Falk, David Huffman, Uwe Sunde, Jürgen Schupp, and Gert G. Wagner. 2011. Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, and Behavioral Consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association 9: 522–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drichoutis, Andreas C., and Jayson L. Lusk. 2016. What Can Multiple Price Lists Really Tell Us about Risk Preferences? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 53: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ertac, Seda. 2020. The Formation and Malleability of Preferences and Noncognitive Skills. Istanbul: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaddar, Ali, Inmaculada Mateo, and Pablo Sanchez. 2008. Occupational Stress and Mental Health among Correctional Officers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Occupational Health 50: 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gizem Korkmaz, Aslihan, Zhichao Yin, Pengpeng Yue, and Haigang Zhou. 2009. Does Financial Knowledge Alleviate Risk Attitude and Risk Behavior Inconsistency? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 39: 137–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Justine S., Brigitte C. Madrian, and William L. Skimmyhorn. 2013. Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Economic Outcomes. Annual Review of Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haushofer, Johannes, and Ernst Fehr. 2014. On the Psychology of Poverty. Science 344: 862–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Pan, Marcella Veronesi, and Stefanie Engel. 2016. Consistency of Risk Preference Measures and the Role of Ambiguity: An Artefactual Field Experiment from China. In Working Paper Series Department of Economics University of Verona. Available online: https://www.usf.uni-osnabrueck.de/fileadmin/DE/Forschung/FG_OEM/wp2016n3.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Hertwig, Ralph, Dirk U. Wulff, and Rui Mata. 2019. Three Gaps and What They May Mean for Risk Preference. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holt, Charles A., and Susan K. Laury. 2002. Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects. American Economic Review 92: 1644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holzmeister, Felix, and Matthias Stefan. 2020. The Risk Elicitation Puzzle Revisited: Across-Methods (in)Consistency? Experimental Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaspersen, Johannes G., Marc A. Ragin, and Justin R. Sydnor. 2020. Linking Subjective and Incentivized Risk Attitudes: The Importance of Losses. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 60: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalra Sahi, Shalini. 2017. Psychological Biases of Individual Investors and Financial Satisfaction. Wiley Online Library 16: 511–35. [Google Scholar]

- Koudstaal, Martin, Randolph Sloof, and Mirjam Van Praag. 2016. Risk, Uncertainty, and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Lab-in-the-Field Experiment. Management Science 62: 2897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurowski, Łukasz. 2021. Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy. Risks 6: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, Pamela M., Sandra Mottner, and Pamela Whalley. 2013. Personal Financial Literacy: Perceptions of Knowledge, Actual Knowledge and Behavior of College Students. Journal of Financial Education 39: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linciano, Nadia, and Paola Soccorso. 2012. Assessing Investors’ Risk Tolerance through a Questionnaire. Social Science Research Network, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnqvist, Jan-Erik, Markku Verkasalo, and Gari Walkowitz. 2015. Measuring Individual Risk Attitudes in the Lab: Task or Ask? An Empirical Comparison. Journal of Economic 119: 254–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lührmann, Melanie, Marta Serra-Garcia, and Joachim Winter. 2018. The Impact of Financial Education on Adolescents’ Intertemporal Choices. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10: 309–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. Financial Literacy around the World: An Overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lusardi, Annamaria. 2019. Financial Literacy and the Need for Financial Education: Evidence and Implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 155: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mandell, Lewis. 2008. Financial Education in High School. In Overcoming the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Inancial Education and Saving Programs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 257–79. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, Jens, and Herbert W. Marsh. 2013. Dimensional Comparison Theory. Psychological Review 120: 544–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzingiri, Calvin. 2019. The Impact of Financial Literacy on Risk and Time Preferences and Financial Behavioural Intentions. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [Google Scholar]

- Mudzingiri, Calvin, Sevias Guvuriro, and Charity Gomo. 2021. Exploring Association between Self-Reported Financial Status and Economic Preferences Using Experimental Data. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, Claudio R., John P. Allegrante, and Marcia Ory. 2002. Theory-Comparison and Multiple-Behavior Research: Common Themes Advancing Health Behavior Research. Health Education Research 17: 670–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, Andreas, Renato Frey, Adrian Bruhin, and Gilles Dutilh. 2017. The Risk Elicitation Puzzle. Nature 1: 803–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem. 2016. Time Series and Panel Data Econometrics. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Statistical Papers 57: 859–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepe, Jan, Michelle Rudeloff, and Theresa Veer. 2020. Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Risk Aversion. Journal of Small Business Management 58: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieider, Ferdinand M, Mathieu Lefebvre, and Ranoua Bouchouicha. 2015. Common Components of Risk and Uncertainty Attitudes across Contexts and Domains: Evidence from 30 Countries. Journal of the European Economic Association 13: 421–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lottery A | Lottery B | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row | P | Rands | p | Rands | p | Rands | p | Rands | Choose A or B | |

| 1 | 0.1 | 60 | 0.9 | 50 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.9 | 25 | A | B |

| 2 | 0.2 | 60 | 0.8 | 50 | 0.2 | 100 | 0.8 | 25 | A | B |

| 3 | 0.3 | 60 | 0.7 | 50 | 0.3 | 100 | 0.7 | 25 | A | B |

| 4 | 0.4 | 60 | 0.6 | 50 | 0.4 | 100 | 0.6 | 25 | A | B |

| 5 | 0.5 | 60 | 0.5 | 50 | 0.5 | 100 | 0.5 | 25 | A | B |

| 6 | 0.6 | 60 | 0.4 | 50 | 0.6 | 100 | 0.4 | 25 | A | B |

| 7 | 0.7 | 60 | 0.3 | 50 | 0.7 | 100 | 0.3 | 25 | A | B |

| 8 | 0.8 | 60 | 0.2 | 50 | 0.8 | 100 | 0.2 | 25 | A | B |

| 9 | 0.9 | 60 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.9 | 100 | 0.1 | 25 | A | B |

| 10 | 1 | 60 | 0 | 50 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 25 | A | B |

| Model | Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | Control Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | PWTFR | Financial literacy | Amount held as cash or in bank account; gender; age; household size; financial decision status; location |

| RE | IRRP | Financial literacy | Amount held as cash or in bank account; gender; age; location; household size; financial decision status; IRRP task |

| RE | RT | Financial literacy | Amount held as cash or in bank account; gender; age; location; household size; financial decision status; IRRP task |

| Variable | Sample (n) | Mean | Std. Err. | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRRP | 772 | 4.70 | 0.08 | 4.54–4.85 |

| Financial literacy | 193 | 40.05 | 0.59 | 38.90–41.20 |

| age | 193 | 22.27 | 0.12 | 22.04–22.50 |

| income | 193 | 1605.21 | 259.56 | 1095.62–2114.80 |

| family members | 193 | 5.37 | 0.12 | 5.14–5.60 |

| PWTFR | 193 | 4.38 | 0.10 | 4.18–4.57 |

| Risk tolerance | 772 | 13.30 | 0.67 | 11.97–14.61 |

| All | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial literacy | −0.00014 | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| (0.137) | (0.164) | (0.188) | |

| Female (gender) | 0.25 * | ||

| (0.130) | |||

| Age | −0.11 | 1.04 * | −2.15 ** |

| (0.516) | (0.566) | (0.881) | |

| Urban (geo location) | −0.074 | −0.27 | 0.061 |

| (0.137) | (0.173) | (0.206) | |

| Income | −0.0059 | −0.037 | 0.024 |

| (0.029) | (0.040) | (0.045) | |

| Joint financial decision-maker | −0.33 ** | −0.31 | −0.30 |

| (0.147) | (0.217) | (0.195) | |

| Main financial decision-maker | −0.12 | −0.33 | −0.0031 |

| (0.144) | (0.217) | (0.193) | |

| Household size | 0.23 * | 0.29 * | 0.23 |

| (0.125) | (0.155) | (0.197) | |

| Constant | 1.25 | −1.82 | 7.23 ** |

| (1.700) | (1.987) | (2.832) | |

| N | 177 | 83 | 94 |

| R2 | 0.072 | 0.156 | 0.125 |

| All | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial literacy | 0.10 *** | −0.037 | 0.23 *** |

| (0.039) | (0.039) | (0.037) | |

| Female (gender) | 0.080 ** | ||

| (0.034) | |||

| Age | 0.75 ** | 0.069 | 1.64 *** |

| (0.329) | (0.211) | (0.417) | |

| Urban (geo location) | −0.13 *** | −0.11 * | −0.18 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.057) | (0.045) | |

| Income | −0.0021 | −0.0081 | −0.0046 |

| (0.010) | (0.019) | (0.007) | |

| Joint financial decision-maker | −0.084 *** | 0.029 | −0.13 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.111) | (0.048) | |

| Main financial decision-maker | −0.14 *** | 0.075 | −0.24 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.078) | (0.047) | |

| Household size | −0.033 | −0.057 | 0.012 |

| (0.031) | (0.046) | (0.043) | |

| IRRP task 1 | 0.015 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.00090 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| IRRP task 2 | −0.0014 *** | 0.017 *** | −0.018 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| IRRP task 3 | 0.040 *** | 0.10 *** | −0.014 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Constant | −0.96 | 1.42 ** | −3.88 *** |

| (1.037) | (0.594) | (1.329) | |

| N | 708 | 332 | 376 |

| All | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial literacy | −0.59 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.74 *** |

| (0.032) | (0.109) | (0.086) | |

| Female (gender) | 0.18 ** | ||

| (0.091) | |||

| Age | 0.45 | −0.12 | 0.40 |

| (0.402) | (0.356) | (0.649) | |

| Urban | −0.048 | 0.27 | −0.50 *** |

| (0.054) | (0.173) | (0.155) | |

| Income | −0.047 *** | −0.054 ** | −0.028 * |

| (0.003) | (0.021) | (0.017) | |

| Joint financial decision-maker | −0.31 *** | −0.0032 | −0.77 *** |

| (0.041) | (0.173) | (0.120) | |

| Main financial decision-maker | −0.12 ** | 0.22 *** | −0.56 *** |

| (0.055) | (0.078) | (0.121) | |

| Household size | 0.022 | −0.20 *** | 0.46 *** |

| (0.073) | (0.068) | (0.065) | |

| IRRP task 1 | 0.071 *** | 0.24 *** | −0.069 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.005) | |

| IRRP task 2 | 0.14 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.034 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| IRRP task 3 | 0.18 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.022 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Constant | 2.11 * | 3.51 *** | 2.75 |

| (1.196) | (1.086) | (1.861) | |

| N | 620 | 290 | 330 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mudzingiri, C.; Koumba, U. Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap? Risks 2021, 9, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9080140

Mudzingiri C, Koumba U. Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap? Risks. 2021; 9(8):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9080140

Chicago/Turabian StyleMudzingiri, Calvin, and Ur Koumba. 2021. "Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap?" Risks 9, no. 8: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9080140

APA StyleMudzingiri, C., & Koumba, U. (2021). Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap? Risks, 9(8), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9080140