Firm-Specific, Macroeconomic and Institutional Determinants of Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

1.2. Contribution

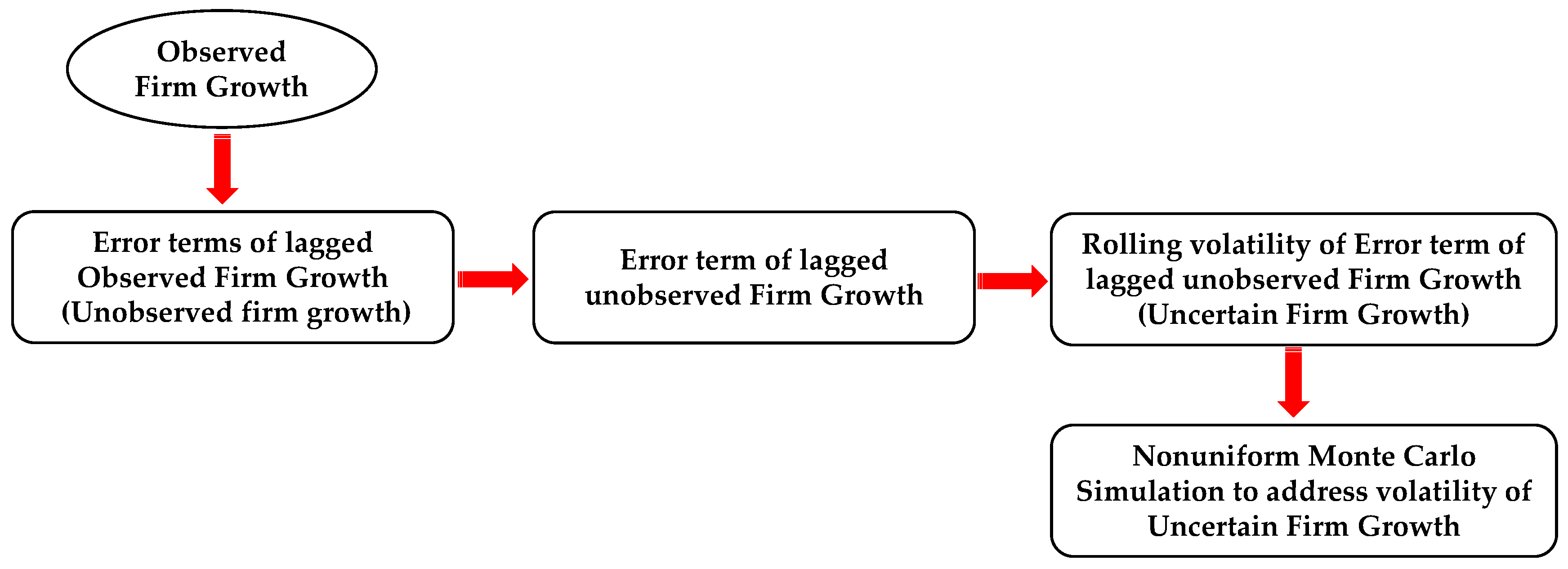

1.3. Measuring the Uncertainty of Firm Growth

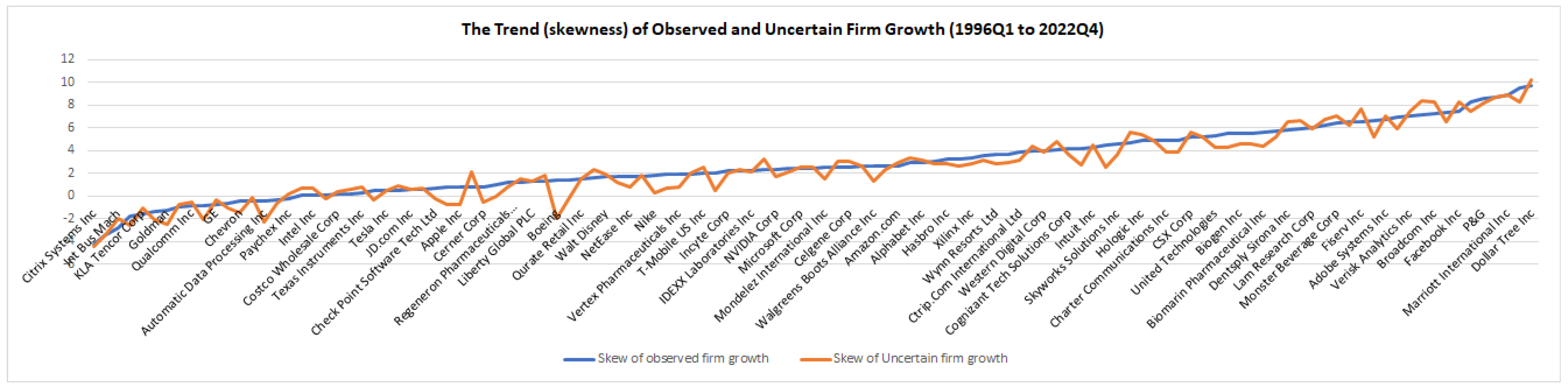

1.4. How Does Observed Firm Growth Differ from Uncertain Firm Growth?

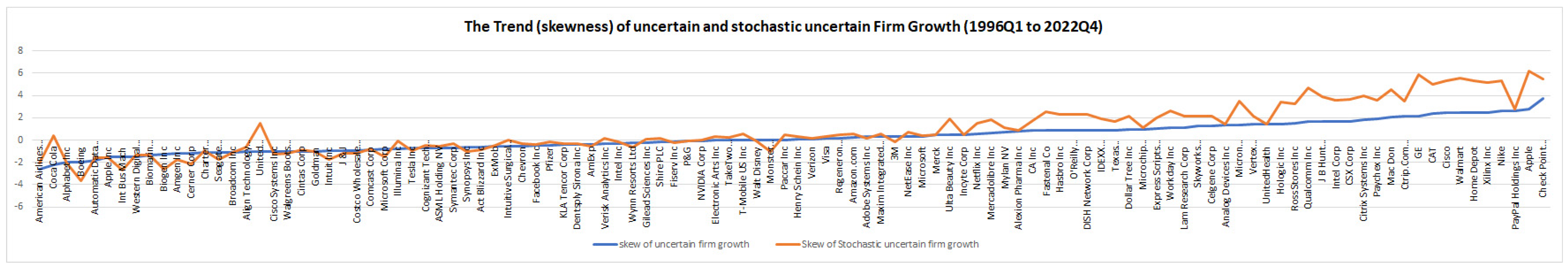

1.5. Empiricism of Stochastic Firm Growth

1.6. How Does Uncertainty Differ from Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Size on Firm Growth

2.2. The Impact of Firm Liquidity on Firm Growth

2.3. The Impact of Stock Market Liquidity on Firm Growth

2.4. The Impact of Macroeconomic Conditions on Firm Growth

2.5. The Impact of Institutional Factors on the Growth of Firms

3. Data, Variables, and Estimation Methods

3.1. Dependent Variables

3.2. Independent Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Firm Specific, Macroeconomic, and Institutional Determinants on the Uncertain Growth of the Firm

4.1.1. The Impact of Firm-Specific Factors on Uncertain Firm Growth

4.1.2. The Impact of Macroeconomic Factors on Uncertain Firm Growth

4.1.3. The Impact of Institutional Factors on Uncertain Firm Growth

4.1.4. Causality Between Realized, Uncertain, and Stochastic Firm Growth

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Descriptive Statistics of the Firm-Specific and Economic Variables

| Variable | Observation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Size | 8835 | 9.1223 | 2.061369 | 1.974081 | 14.11256 |

| Growth of EBT | 8835 | −0.0232481 | 8.463706 | −578.5833 | 213.5 |

| Liquidity Ratio | 8835 | 2.609854 | 7.304959 | −223 | 253.531 |

| Fixed Asset Turnover | 8835 | 0.5878805 | 0.805901 | −1 | 47 |

| Current Asset Turnover | 8835 | 0.6279678 | 5.065948 | −147.6216 | 323.1333 |

| Age of the Firm | 8835 | 44.35068 | 39.40117 | 1 | 185 |

| EBDIT Margin | 8835 | −0.3266939 | 8.018948 | −437 | 8.6 |

| D/E Ratio | 8835 | 2.334104 | 66.09045 | −819.4565 | 6769 |

| Tobin Q Ratio | 8835 | 6.179377 | 53.2762 | −0.7622446 | 2457.989 |

| Inflation Rate | 8835 | 0.0058124 | 0.0059666 | −0.0282853 | 0.0219534 |

| Capital Market Illiquidity (Relative Spread) | 8835 | 0.0921618 | 0.0595566 | 0.0251646 | 0.3192663 |

| Natural Rate of Unemployment | 8835 | 0.0505518 | 0.0036119 | 0.046023 | 0.058472 |

| Real GDP Growth | 8835 | 0.0063724 | 0.005472 | −0.0221334 | 0.018049 |

| Net Exports of Goods and Services | 8835 | 0.0212687 | 0.0887835 | −0.3301362 | 0.2724993 |

| Business Cycle | 8835 | 0.4791096 | 0.4995848 | 0 | 1 |

Appendix B. Descriptive Statistics of Institutional Factors (Ranks of World Governance Indicators)

| Variable | Observation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Control of Corruption | 8835 | 89.73691 | 2.285031 | 84.7619 | 92.61084 |

| Government Effectiveness | 8835 | 91.0426 | 1.141904 | 88.57143 | 93.20388 |

| Political Stability & Absence of Violence | 8835 | 62.3911 | 10.86973 | 37.37864 | 82.53968 |

| Regulatory Quality | 8835 | 92.43914 | 2.721771 | 85.2381 | 95.65218 |

| Rule of Law | 8835 | 91.69821 | 0.908669 | 89.04762 | 93.03483 |

| Voice & Accountability | 8835 | 86.01742 | 3.925081 | 80.09708 | 92.0398 |

Appendix C. Results of the Endogeneity Test

| Variable | Residual | Coefficient |

| Realized Growth Rates | RESID01 | −0.116078 (−0.8369) |

| Growth of Wages | RESID1 | 0.000548 (0.45908) |

| Firm Size (Ln Total Assets) | RESID2 | 0.368714 (10.3091) *** |

| Growth of Earnings before Taxes | RESID3 | 1.22 × 1015 (0.244315) |

| Sales Revenue Growth Rate | RESID4 | −0.002713 (−0.12018) |

| Retention Ratio | RESID5 | −0.000208 (−0.16574) |

| Liquidity Ratio | RESID6 | −0.002507 (−0.97968) |

| Long-Term Finance | RESID7 | −0.032614 (−0.303966) |

| Profit Margin | RESID8 | 3.26 × 1012 (0.151109) |

| Fixed Assets Turnover | RESID9 | 0.013384 (1.577624) |

| Current Assets Turnover | RESID10 | 0.003866 (0.735199) |

| Capital Intensity | RESID11 | −2.061498 (−15.143) *** |

| EBDIT Margin | RESID12 | −0.00032 (−0.095136) |

| DE Ratio | RESID13 | −0.000178 (−0.4526) |

| Tobin Q Ratio | RESID14 | −0.004584 (−7.5748) *** |

| Cash Flow to Total Assets | RESID15 | −1.49 × 101 (−0.15145) |

| Profitable Growth | RESID16 | −1.49 × 1011 (0.66236) |

| Inflation Rate | RESID17 | −4.606688 (−0.11705) |

| Relative Spread | RESID18 | 0.851122 (0.10897) |

| Illiquidity Ratio | RESID19 | 1229.644 (0.108139) |

| Implicit Spread Estimator | RESID20 | −0.000164 (−0.044013) |

| Natural Rate of Unemployment | RESID21 | 54.73737 (0.07822) |

| GDP Growth Real | RESID22 | −2.3118 (−0.032129) |

| Effective FFR | RESID23 | 9.406621 (0.11563) |

| Net Exports of Goods and Services | RESID24 | 0.179293 (0.060782) |

| Stock Market Skewness | RESID25 | 0.481553 (0.086462) |

| Business Cycle | RESID26 | 0.015916 (0.030109) |

| Economic Policy Uncertainty | RESID27 | −0.131601 (−0.123537) |

| Control of Corruption: Percentile Rank | RESID28 | 0.697332 (0.018464) |

| Government Effectiveness: Percentile Rank | RESID29 | 3.78439 (0.082255) |

| Political Stability: Percentile Rank | RESID30 | −0.097426 (−0.019939) |

| Regulatory Quality: Percentile Rank | RESID31 | 2.09186 (0.086444) |

| Rule of Law: Percentile Rank | RESID32 | −0.275361 (−0.005002) |

| Voice and Accountability: Percentile Rank | RESID33 | 2.203613 (0.055942) |

| *** Significant at 1%. |

Appendix D. Results of Chow Structural Break Test

| Wald Statistic [p Value, Chi-Square (34)] | ||

| Breakpoint (Financial Crisis) | Uncertain Firm Growth | Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth |

| 2008Q1 | 3.344775 (1.00) | 1.904094 (1.00) |

| 2008Q2 | 3.385225 (1.00) | 1.924102 (1.00) |

| 2008Q3 | 3.413509 (1.00) | 1.955057 1.00) |

| 2008Q4 | 3.425298 (1.00) | 1.97067 (1.00) |

References

- Adelman, Irma G. 1958. A stochastic analysis of the size distribution of firms. Journal of the American Statistical Association 53: 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, Priyanka Aman. 2015. An empirical evidence of measuring growth determinants of Indian firms. Journal of Applied Finance and Banking 5: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Aizenman, J., and N. P. Marion. 1999. Volatility and Investment: Interpreting Evidence from Developing Countries. Economica 66: 157–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarano, Simone, Mishael Milaković, Albrecht Irle, and Jonas Kauschke. 2012. A statistical equilibrium model of competitive firms. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control 36: 136–49. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehadeh, Abdul Razzak, Ahmad Adel Jamil Abdallah, Farid Kourtel, Ihab Ali El-Qirem, and Ehab Injadat. 2023. The impact of cash liquidity on sustainable financial growth: A study on ASE-listed industrial companies. In Conference on Sustainability and Cutting-Edge Business Technologies. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Amihud, Yakov. 2002. Illiquidity and stock returns: Cross-section and time-series effects. Journal of Financial Markets 5: 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, Sorin Gabriel. 2016. The impact of leverage on firm growth. empirical evidence from Romanian listed firms. Review of Economic and Business Studies 9: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arata, Yoshiyuki. 2019. Firm growth and Laplace distribution: The importance of large jumps. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control 103: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, Ruediger, Kai Carstensen, Stefan Lautenbacher, and Martin Schneider. 2021. Uncertainty and Change: Survey Evidence of Firms’ Subjective Beliefs. (No. w29430). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine, John W., Frederick W. Cleveland, and C. Timothy Koeller. 1993. Profitability, uncertainty, and firm size. Small Business Economics 5: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, Natália, and Vasco Eiriz. 2011. Regional Variation of Firm Size and Growth: The Portuguese Case. Growth and Change 42: 125–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basovskaya, Elena, and L. Basovskiy. 2024. The impact of unemployment on wages and profits. Scientific Research and Development Economics 12: 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Utpal, Po-Hsuan Hsu, Xuan Tian, and Yan Xu. 2017. What affects innovation more: Policy or policy uncertainty? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52: 1869–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Hong. 2002. Idiosyncratic Uncertainty and Firm Investment. Australian Economic Papers 41: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borraz, Fernando, and Diego Gianelli. 2010. A Behavior Analysis of the BCU Inflation Expectation Survey, MPRA Paper, 27713. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/27713/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Bottazzi, Giulio, and Angelo Secchi. 2003a. A stochastic model of firm growth. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 324: 213–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Giulio, and Angelo Secchi. 2003b. Common Properties and Sectoral Specificities in the Dynamics of U.S. Manufacturing Companies. Review of Industrial Organization 23: 217–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Giulio, and Angelo Secchi. 2006. Explaining the distribution of firm growth rates. RAND Journal of Economics 37: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Giulio, Elena Cefis, and Giovanni Dosi. 2002. Corporate Growth and Industrial Structure. Some Evidence from the Italian Manufacturing Industry. Industrial and Corporate Change 11: 705–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Giulio, Alex Coad, Nadia Jacoby, and Angelo Secchi. 2011. Corporate growth and industrial dynamics: Evidence from French manufacturing. Applied Economics 43: 103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Giulio, Angelo Secchi, and Federico Tamagni. 2012. Financial Constraints and Firm Dynamics. Small Business Economics 42: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, Trevor S., and Adrian R. Pagan. 1979. A Simple Test for Heteroscedasticity and Random Coefficient Variation. Econometrica 47: 1287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, Juan Gabriel, Bibiana Lanzilotta, and Lucia Rosich. 2024. On the dynamics of expectations, uncertainty and economic growth: An empirical analysis for the case of Uruguay. International Journal of Emerging Markets 19: 2385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, Anže, Andreja Jaklič, Klemen Knez, Patricia Kotnik, and Matija Rojec. 2024. Firm-Level, macroeconomic, and institutional determinants of firm growth: Evidence from Europe. Economic and Business Review 26: 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, Anže, Jože P. Damijan, Črt Kostevc, and Matija Rojec. 2017. Determinants of firm performance and growth during economic recession: The case of Central and Eastern European countries. Economic Systems 41: 569–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, Flavio, Chiara Criscuolo, Carlo Menon, and Angelo Secchi. 2018. Growth volatility and size: A firm-level study. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control 90: 390–407. [Google Scholar]

- Cardao-Pito, Tiago. 2022. Hypothesis that Tobin’s Q captures organizations’ debt levels instead of their growth opportunities and intangible assets. Cogent Economics & Finance 10: 2132636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, Alex, Agustí Segarra, and Mercedes Teruel. 2013. Like milk or wine: Does firm performance improve with age? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 24: 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, Alex, and Werner Hölzl. 2009. On the autocorrelation of growth rates: Evidence for micro, small and large firms from the Austrian service industries, 1975–2004. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 9: 139–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danbolt, Jo, Ian R. C. Hirst, and Eddie Jones. 2010. The growth companies puzzle: Can growth opportunities measures predict firm growth? European Journal of Finance 17: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Steven J., Stephen Hansen, and Cristhian Seminario-Amez. 2025. Macro Shocks and Firm-Level Response Heterogeneity. Working Paper No. 2025-87. Chicago: Becker Friedman Institute of Economics, The University of Chicago, pp. 2025–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, Aslıhan Atabek, and H. Burcu Gürcihan Yüncüler. 2017. Employment Growth and Uncertainty: Evidence from Turkey. IFC Bulletins Chapters 45: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Doane, David P., and Lori E. Seward. 2011. Measuring skewness: A forgotten statistic? Journal of Statistics Education 19: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, Vivek Kumar, and Arindam Das. 2021. Role of governance on SME exports and performance. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 24: 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschl, Matthias. 2014. Regional Resilience and Fat Tails: A Stochastic Analysis of Firm Growth Rate Distributions of German Regions. Working Papers on Innovation and Space. No. 01.14. Marburg: Philipps-University Marburg, Department of Geography. [Google Scholar]

- Eldomiaty, Tarek, Marina Apaydin, Jasmin Fouad, Marwa Anwar, and Heba El Zahed. 2023. Firm Growth and Total Factor Productivity: A methodology for Examining the Size Controversy. International Journal of Business and Economics 22: 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, Aysa Ipek. 2023. Drivers of SME growth: Quantile regression evidence from developing countries. SAGE Open 13: 21582440231163479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, David S. 1987. The relationship between firm growth, size and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. The Journal of Industrial Economics 35: 567–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiolo, Giorgio, and Alessandra Luzzi. 2006. Do liquidity constraints matter in explaining firm size and growth? Some evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry. Industrial and Corporate Change 15: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeny, Simon, and Mark Rogers. 1999. The Performance of Large Private Australian Enterprises. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. Melbourne Institute Working Paper No. 2/99. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, Giuseppe, and Filippo Scoccianti. 2023. The economic effects of firm-level uncertainty: Evidence using subjective expectations. Journal of Monetary Economics 140: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, Michael, Stephen X. Gong, and Liwei Shan. 2013. Cost of government and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance 21: 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Dongfeng, Fabio Pammolli, S. V. Buldyrev, Massimo Riccaboni, Kaushik Matia, Kazuko Yamaski, and H. Eugene Stanley. 2005. The growth of business firms: Theoretical framework and empirical evidence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102: 18801–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geroski, Paul A., Stephen J. Machin, and Christopher F. Walters. 1997. Corporate growth and profitability. Journal of Industrial Economics 45: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, Ahmad Mohammad Obeid, and Adel Mohammed Sarea. 2015. The impact of capital structure and certain firm specific variables on the value of the firm: Empirical evidence from Kuwait. Corporate Ownership and Control 13: 1191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, Vivek, and Prakash Loungani. 1996. Product Market Competition and the Impact of Price Uncertainty on Investment: Some Evidence from U.S. Manufacturing Industries. The Journal of Industrial Economics 44: 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, Vivek, and Prakash Loungani. 2000. The Differential Impact of Uncertainty on Investment in Small and Large Businesses. Review of Economics and Statistics 82: 338–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Amarjit, and Neil Arun Mathur. 2011. Factors that Affect Potential Growth of Canadian Firms. Journal of Applied Finance and Banking 1: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Glancey, Keith. 1998. Determinants of growth and profitability in small entrepreneurial firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 4: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, Huseyin, and Mihai Ion. 2016. Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. The Review of Financial Studies 29: 523–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermelo, Francisco Diaz, and Roberto S. Vassolo. 2007. The determinants of firm growth: An empirical examination. Revista Abante 10: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Holly, Sean, Ivan Petrella, and Emiliano Santoro. 2013. Aggregate Fluctuations and the Cross-sectional Dynamics of Firm Growth. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (A) 176: 459–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijiri, Y., and H. Simon. 1997. Skew Distributions and the Sizes of Business Firms. Amsterdam: North Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, SooCheong (Shawn). 2011. Growth-focused or profit-focused firms: Transitions toward profitable growth. Tourism Management 32: 667–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, Ivan. 2010. Firm as a Nexus of Markets. Journal des Economistes et des Etudes Humaines 16: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Morten Berg, and Toke Reichstein. 2003. Analyzing the Distributions of the Stochastic Firm Growth Approach. Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics. DRUID Working Paper No. 12. Available online: https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/analyzing-the-distributions-of-the-stochatic-firm-growth-approach (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Kadry, Seifedine. 2015. Monte Carlo Simulation Using Excel: Case Study in Financial Forecasting. In The Palgrave Handbook of Research Design in Business and Management. Edited by Kenneth D. Strang. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Wensheng, Kiseok Lee, and Ronald A. Ratti. 2014. Economic policy uncertainty and firm-level investment. Journal of Macroeconomics 39: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Kuldip. 2024. Size Growth and Profitability of Firms Economics, Management, Commerce. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Arif, Xuezhi Qin, and Khalil Jebran. 2019. Does uncertainty influence the leverage-investment association in Chinese firms? Research in International Business and Finance 50: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Arif, Xuezhi Qin, Khalil Jebran, and Abdul Rashid. 2020. The sensitivity of firms’ investment to uncertainty and cash flow: Evidence from listed state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises in China. Sage Open 10: 2158244020903433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Cheonkoo, Jungsoo Park, Donghyun Park, and Shu Tian. 2022. Heterogeneous Effect of Uncertainty on Corporate Investment: Evidence from Listed Firms in the Republic of Korea. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, Holger, Eduardo Schwartz, and Farina Weiss. 2017. Growth options and firm valuation. European Financial Management 24: 209–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Mihye. 2023. Determinants of Firm-Level Growth: Lessons from the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. South East European Journal of Economics and Business 18: 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, Robert, Paul van Steen, and Elmer Sterken. 2005. Uncertainty and Growth of the Firm. Small Business Economics 24: 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Listiani, Nur, and Supramono Supramono. 2020. Sustainable growth rate: Between fixed asset growth and firm value. Management and Economics Review 5: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wan-Chun, and Chen-Min Hsu. 2006. Financial structure, corporate finance and growth of Taiwan’s manufacturing firms. Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets and Policies/Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets and Policies 9: 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, Diogo, and Jorge Cerdeira. 2024. Too much of a good thing? The concave impact of corruption on firm performance. Cogent Business & Management 11: 2378916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttmer, Erzo G. J. 2011. On the Mechanics of Firm Growth. Review of Economic Studies 78: 1042–68. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23015839 (accessed on 6 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Majudmar, Sumit K. 1997. The Impact of Size and Age on Firm-Level Performance: Some Evidence from India. Review of Industrial Organization 12: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinić, Dejan, Ksenija Denčić-Mihajlov, and Konrad Grabiński. 2020. Reexamination of the determinants of firms’ growth in periods of crisis. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci: Časopis za Ekonomsku Teoriju i Praksu 38: 101–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mateev, Miroslav, and Yanko Anastasov. 2010. Determinants of small and medium sized fast-growing enterprises in central and eastern Europe: A panel data analysis. Financial Theory and Practice 34: 269–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mowery, David C. 1983. Industrial Research and Firm Size, Survival, and Growth in American Manufacturing, 1921–1946: An assessment. The Journal of Economic History 43: 953–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Tutun, and Som Sankar Sen. 2018. Sustainable growth rate and its determinants: A study on some selected companies in India. Account and Financial Management Journal 10: 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwombeki, Frank A. 2023. Influencing Attributes on Revenue Growth: An Empirical Analysis from SMEs in Tanzania. Journal of Accounting, Finance and Auditing Studies 9: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, K. 1998. Technology acquisition, de-regulation and competitiveness: A study of Indian automobile industry. Research Policy 27: 215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næs, Randi, Johannes A. Skjeltorp, and Bernt Arne Ødegaard. 2011. Stock market liquidity and the business cycle. The Journal of Finance 66: 139–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaki, Masahiko, Bo Gustafsson, and Oliver E. Williamson. 1990. The Firm as a Nexus of Treaties. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Edith Tilton. 2009. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ponikvar, Nina, Maks Tajnikar, and Petra Došenović Bonča. 2022. Triggers of different types of firm growth. Economic and Business Review 24: 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, Shiva Raj. 2017. Impact of firm specific and macroeconomic variables on firm growth: Evidence from Nepal. ACADEMICIA: An International Multidisciplinary Research Journal 7: 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich, Joel. 2023. Tangible and intangible investments and sales growth of US firms. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 66: 200–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, P., J. Nirubarani, and S. Mekala. 2024. A Study on Addressing Unemployment: Strategies and Policies for Enhancing Job Creation. NPRC Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 1: 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, Ruth. 1999. Growth in food and drink multinationals, 1977–94: An empirical investigation. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 10: 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J. B. 1969. Tests for Specification Errors in Classical Linear Least Squares Regression Analysis. Journal of Royal Statistical Society B 31: 350–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginster, Alexandre. 2021. Stochastic analysis of firm dynamics: Their impact on the firm size distribution. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 570: 125817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccaboni, Massimo, Fabio Pammolli, Sergey V. Buldyrev, Linda Ponta, and H. E. Stanley. 2008. The size variance relationship of business firm growth rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 19595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, Richard. 1984. A simple implicit measure of the effective Bid—Ask spread in an efficient market. The Journal of Finance 39: 1127–39. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, Paul M. 1990. Endogenous Technological Change. Journal of Political Economy 98: S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, K. R., and Saumitra N. Bhaduri. 2002. Size, age and firm growth in the Indian manufacturing sector. Applied Economics Letters 9: 607–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, Abdullahi, Saifullahi Sani Ibrahim, and Zulaihatu A. Zubair. 2024. Impact of Institutional Quality on Private Sector Investment in Economic Community of West African States. Gusau Journal of Economics and Development Studies 5: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddharthan, N. S., B. L. Pandit, and R. N. Agarwal. 1994. Growth And Profit Behavior of Large—Scale Indian Firms. The Developing Economies 32: 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, Bojana, Kristina Peštović, Vera Mirović, Dejan Jakšić, and Sunčica Milutinović. 2022. The analysis of company growth determinants based on financial statements of the European companies. Sustainability 14: 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yizhong, Carl R. Chen, and Ying Sophie Huang. 2014. Economic policy uncertainty and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 26: 227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Shiyi, and Rui Niu. 2025. Navigating the Uncertainty: Unveiling the Impact of Trade Policy Uncertainty on GVC Ascent in Chinese Listed Companies. International Studies of Economics, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Inder Sekhar, Debasis Pahi, and Rajesh Gangakhedkar. 2021. The nexus between firm size, growth and profitability: New panel data evidence from Asia–Pacific markets. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 31: 115–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, Nahid, Gregor Pfajfar, John W. Cadogan, Maciej Mitręga, Eleni Lioliou, Ruey-Jer “Bryan” Jean, Ian R. Hodgkinson, Eleni (Lenia) Tsougkou, Vicky M. Story, Nathaniel Boso, and et al. 2023. Cooperative export channel modes in times of uncertainty, a key to born global firms’ survival? Paper presented at the Industrial Marketing Management Summit 2023, Bamberg, Germany, January 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhikai, Mengxi He, Yaojie Zhang, and Yudong Wang. 2021. Realized skewness and the short-term predictability for aggregate stock market volatility. Economic Modelling 103: 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhorzholiani, Tinatin. 2024. The Impact of Unemployment on Economic Development: Georgia’s Example. European Scientific Journal 20: 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measurement | |

|---|---|---|

| Firm-specific variables | Size of the firm | Natural log of total Assets (Evans 1987; Calvino et al. 2018; Gill and Mathur 2011) |

| Growth in Earnings before tax | (Kaur 2024; Liu and Hsu 2006) | |

| Liquidity Ratio | Current Asset/Current Liability (Kaur 2024; Gill and Mathur 2011) | |

| Fixed Asset Turnover | Net sales revenue/average Fixed assets (Kaur 2024; Rabinovich 2023) | |

| Current Asset Turnover | Net sales revenue/average Current assets (Kaur 2024) | |

| Age of the firm | Number of years since establishment (Age (Glancey 1998; Coad et al. 2013) | |

| EBIT Margin | EBIT/Total Revenue (Feeny and Rogers 1999) | |

| Debt to Equity Ratio | Total Liabilities/Shareholder’s Equity (Feeny and Rogers 1999) | |

| Tobin Q ratio | Market Value of Firm/Replacement Cost of Assets (Feeny and Rogers 1999; Danbolt et al. 2010) | |

| Capital intensity | Majudmar (1997) | |

| Macroeconomic Variables | Inflation Rate | Quarterly % change in CPI (Poudel 2017; Malinić et al. 2020) |

| Capital Market Illiquidity | Relative spread being measured as the ratio of ask–bid stock price to the average of ask–bid price. (Næs et al. 2011) | |

| Natural Rate of Unemployment | Natural unemployment/Total employment (Næs et al. 2011) | |

| Real GDP Growth Rate | (Poudel 2017) | |

| Interest Rate | Effective Federal Fund Rate (Zhang et al. 2021) | |

| Business Cycle | Skewness of quarterly GDP growth (Gulen and Ion 2016; Næs et al. 2011) | |

| Institutional variables | World Governance indicators | Control of Corruption; Government Effectiveness; Political Stability & Absence of Violence; Regulatory Quality; Rule of Law; Voice & Accountability (Shehu et al. 2024) https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 21 August 2023) |

| Variable | Model 1: Base Model Including Firm-Specific | Model 2: Base Model and Macroeconomic Factors | Model 3: Basic Model and Institutional Factors (WGI) | Model 4: Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.105173 (60.516) *** | 1.166892 (30.804) *** | −6.247053 (−4.424) *** | 1.2556 (1.7453) * |

| Realized Firm Growth Rates | 0.015948 (4.8942) *** | 0.014361 (4.9824) *** | 0.012793 (4.492) *** | 2.07 × 105 (0.0088) |

| Growth Rate of Wages | 3.62 × 1011 (23.5365) *** | 3.65 × 1011 (19.45613) *** | 3.51 × 1011 (19.836) *** | 4.01 × 1013 (0.2776) |

| 13Firm Size (Ln Total Assets) | −3.99 × 106 (−2.3313) ** | 4.8 × 105 (6.1788) *** | 0.000111 (14.040) *** | 4.73 × 108 (0.01171) |

| Growth of Earnings before Taxes | −1.58 × 1045 (−8.571) *** | −1.65 × 1045 (−9.0181) *** | −1.72 × 1045 (−9.0170) *** | −4.55 × 1046 (−2.9253) *** |

| EBDIT Margin | −9.5 × 109 (−4.4513) *** | −8.83 × 109 (−3.4952) *** | −8.31 × 109 (−3.3192) *** | −1.88 × 108 (−2.4112) *** |

| Cash Flow to Total Assets | −6.88 × 1041 (−10.124) *** | −2.16 × 1041 (−2.5520) ** | −8.07 × 1041 (−8.6167) *** | 1.11 × 1041 (1.0626) |

| Sales Revenue Growth Rate | 1.68 × 107 (1.25412) | 3.71 × 107 (0.98822) | 3.85 × 107 (0.8435) | −2.41 × 107 (−2.2252) ** |

| Retention Ratio | 1.16 × 1011 (2.2696) ** | 2.03 × 1011 (1.2031) | 1.84 × 1011 (1.0468) | 4.96 × 1012 (1.2745) |

| Liquidity Ratio | 7.58 × 1010 (5.2272) *** | 8.84 × 1010 (4.05145) *** | 8.69 × 1010 (4.1257) *** | −1.58 × 1010 (−1.5674) |

| Long Term Finance | −0.004423 (−60.0246) *** | −0.004623 (−53.883) *** | −0.00482 (−46.917) *** | −0.000105 (−0.2607) |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | 1.09 × 1013 (3.3616) *** | 1.01 × 1013 (3.6748) *** | 1.17 × 1013 (5.022) **** | −2.32 × 1014 (−2.4475) ** |

| Fixed Assets Turnover | −6.79 × 109 (−0.72146) | 5.33 × 108 (2.25907) ** | 9.48 × 108 (2.7037) *** | −5.29 × 1010 (−0.0241) |

| Current Assets Turnover | 4.71 × 1011 (0.341161) | −2.08 × 1010 (−0.44518) | 6.85 × 1011 (0.08924) | 1.07 × 109 (0.6629) |

| Capital Intensity | 0.003024 (0.85454) | 0.0013 (0.43476) | 0.000284 (0.1163) | 0.001091 (1.0701) |

| Tobin Q Ratio | −6.11 × 1010 (−3.0902) *** | −6.11 × 1010 (−3.0852) *** | −6.07 × 1010 (−3.0859) *** | −6.97 × 1011 (−0.4447) |

| Inflation Rate | −515.0312 (−1.1103) | 168.071 (0.70204) | ||

| Relative Spread | 1.36177 (5.0158) *** | 0.2433 (2.0662) ** | ||

| Stock Illiquidity Ratio | 2.63 × 101 (0.10649) | −1.84 × 108 (−1.0047) | ||

| Implicit Spread Estimator | −0.000692 (−0.9913) | −0.000728 (−2.0152) ** | ||

| Natural Rate of Unemployment | 188.110 (3.9203) *** | 19.1018 (0.3381) | ||

| GDP Growth Real | 879.96 (0.7694) | 59.146 (0.122151) | ||

| Effective FFR | 71.6917 (2.6002) ** | −13.1177 (−0.78491) | ||

| Net Exports of Goods and Services | 0.02582 (0.11179) | 0.216525 (2.9089) *** | ||

| Stock Market Skewness | 0.00434 (0.4146) | 0.003452 (0.7056) | ||

| Business Cycle | 0.00241 (0.7949) | 0.0003 (0.2191) | ||

| Economic Policy Uncertainty | −0.0287 (−3.286) *** | 0.004871 (1.1376) | ||

| Control of Corruption: Percentile Rank | 0.134889 (1.52922) | 0.06081 (0.6648) | ||

| Government Effectiveness: Percentile Rank | 0.103155 (0.66352) | −0.13990 (−1.2309) | ||

| Political Stability: Percentile Rank | 0.034671 (4.4406) *** | −0.00896 (−1.3317) | ||

| Regulatory Quality: Percentile Rank | 0.341999 (3.1215) *** | 0.0308 (0.5993) | ||

| Rule of Law: Percentile Rank | 0.04184 (0.11503) | 0.10641 (0.718984) | ||

| Voice and Accountability: Percentile Rank | 0.956762 (12.232) *** | −0.052993 (−0.6849) | ||

| Industry Dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.827122 | 0.800431 | 0.796214 | 0.790206 |

| S.E. of Regression | 1.775302 | 1.454672 | 1.396973 | 1.551689 |

| Durbin–Watson Stat | 0.184303 | 0.132753 | 0.119743 | 2.033521 |

| Mean Dependent Var | 3.733241 | 2.48034 | 2.26366 | 2.886373 |

| S.D. Dependent Var | 3.511758 | 2.923884 | 2.847541 | 2.751794 |

| Sum Squared Resid | 39,610.54 | 26,571.5 | 24,515.18 | 30,219.52 |

| J-Statistic | 2.11 × 10−16 | 2.30 × 10−16 | 4.07 × 10−6 | 4.96 × 10−6 |

| Null Hypothesis: | F-Statistic |

|---|---|

| Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Uncertain Firm Growth | 87.2163 *** |

| Uncertain Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth | 691.333 *** |

| Realized Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Uncertain Firm Growth | 0.00655 |

| Uncertain Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Realized Firm Growth | 27.993 *** |

| Realized Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth | 0.01152 |

| Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth does not Granger Cause Realized Firm Growth | 0.3852 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eldomiaty, T.; Azzam, I.A.A.; El Kolaly, H.; Apaydin, M.; William, M. Firm-Specific, Macroeconomic and Institutional Determinants of Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth. Risks 2025, 13, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100183

Eldomiaty T, Azzam IAA, El Kolaly H, Apaydin M, William M. Firm-Specific, Macroeconomic and Institutional Determinants of Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth. Risks. 2025; 13(10):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100183

Chicago/Turabian StyleEldomiaty, Tarek, Islam Abdel Azim Azzam, Hoda El Kolaly, Marina Apaydin, and Monica William. 2025. "Firm-Specific, Macroeconomic and Institutional Determinants of Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth" Risks 13, no. 10: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100183

APA StyleEldomiaty, T., Azzam, I. A. A., El Kolaly, H., Apaydin, M., & William, M. (2025). Firm-Specific, Macroeconomic and Institutional Determinants of Stochastic Uncertain Firm Growth. Risks, 13(10), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100183